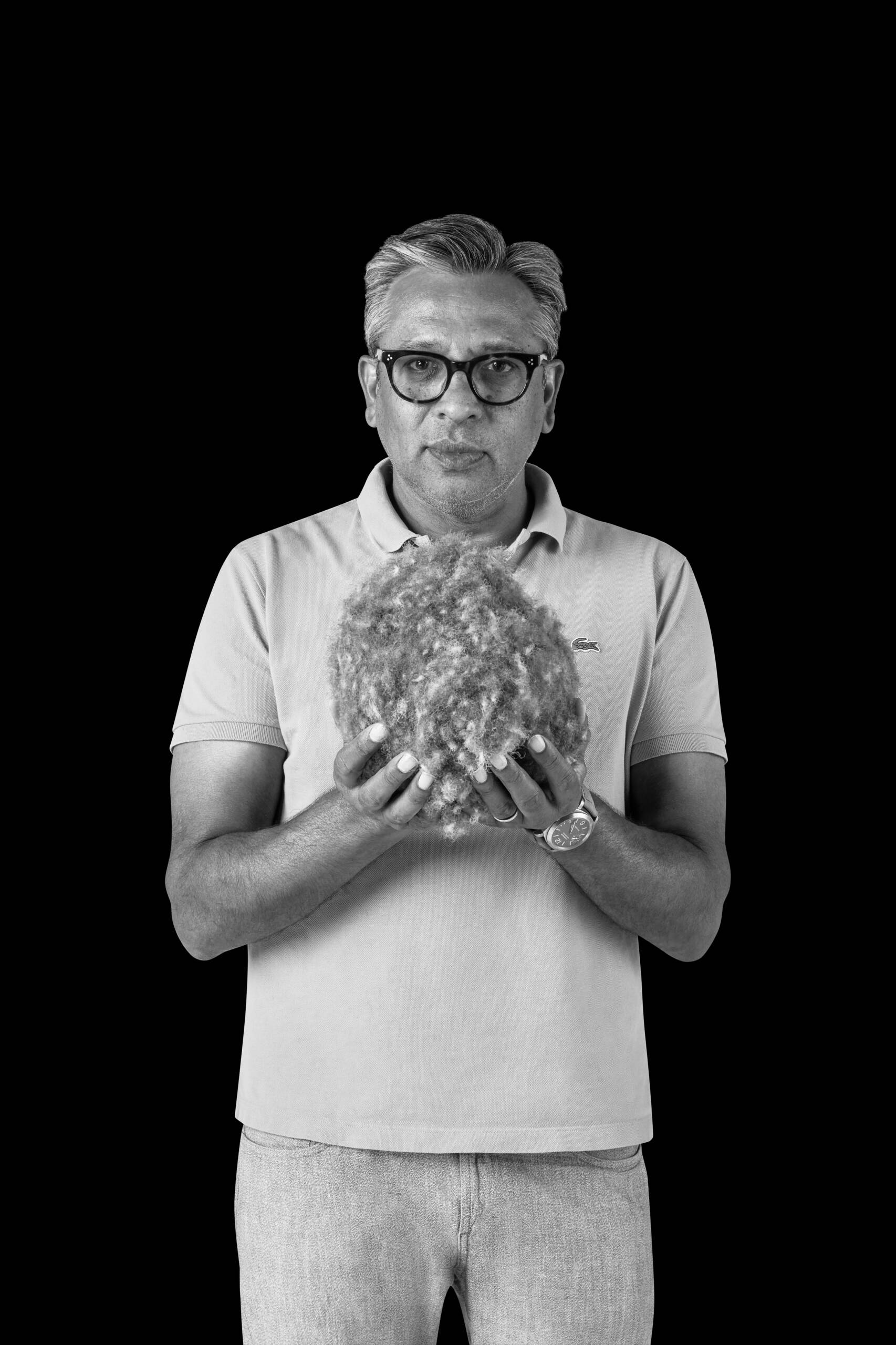

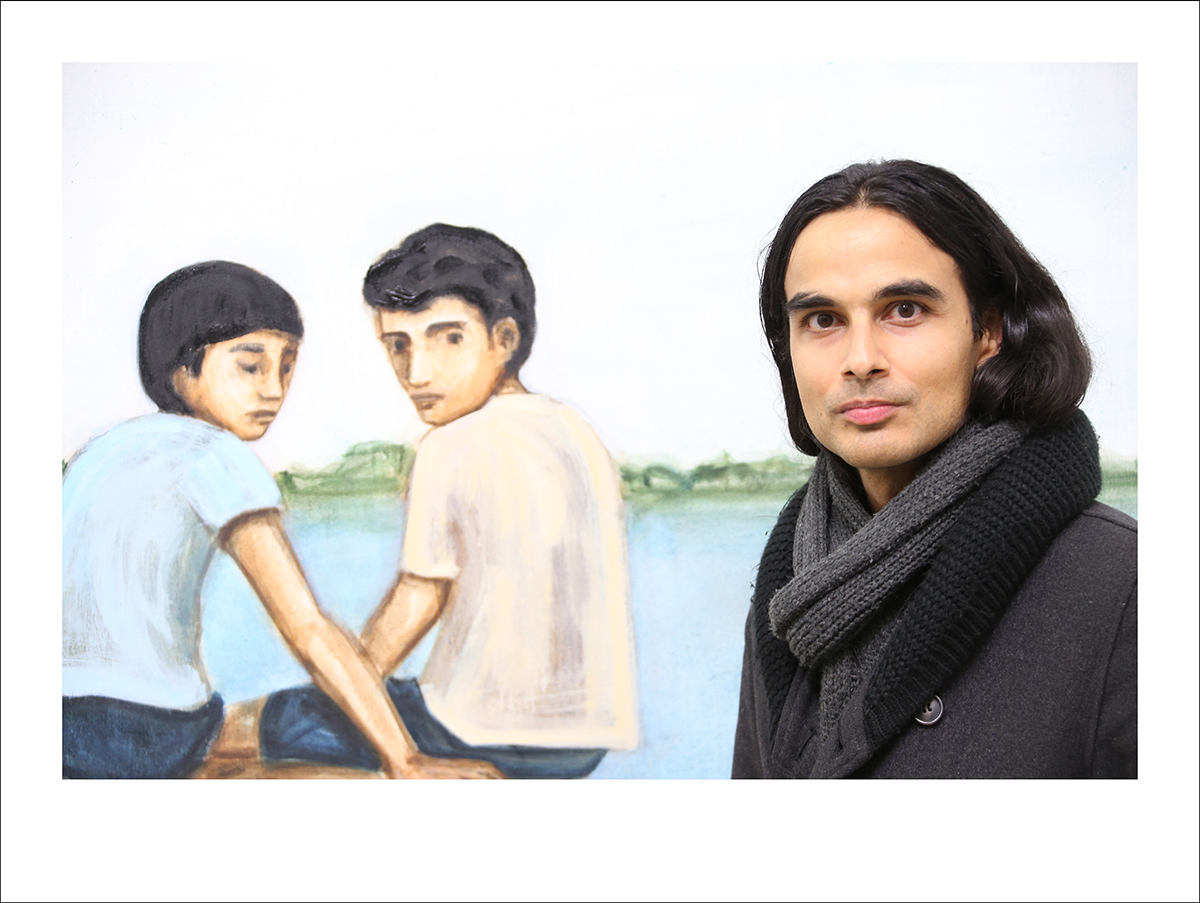

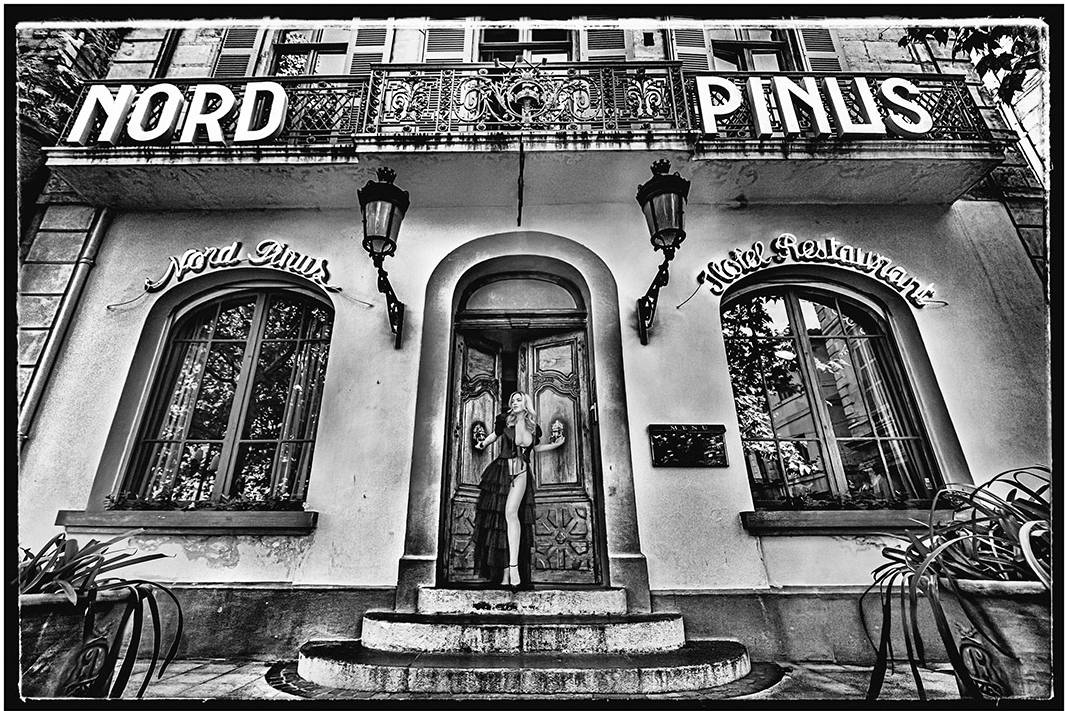

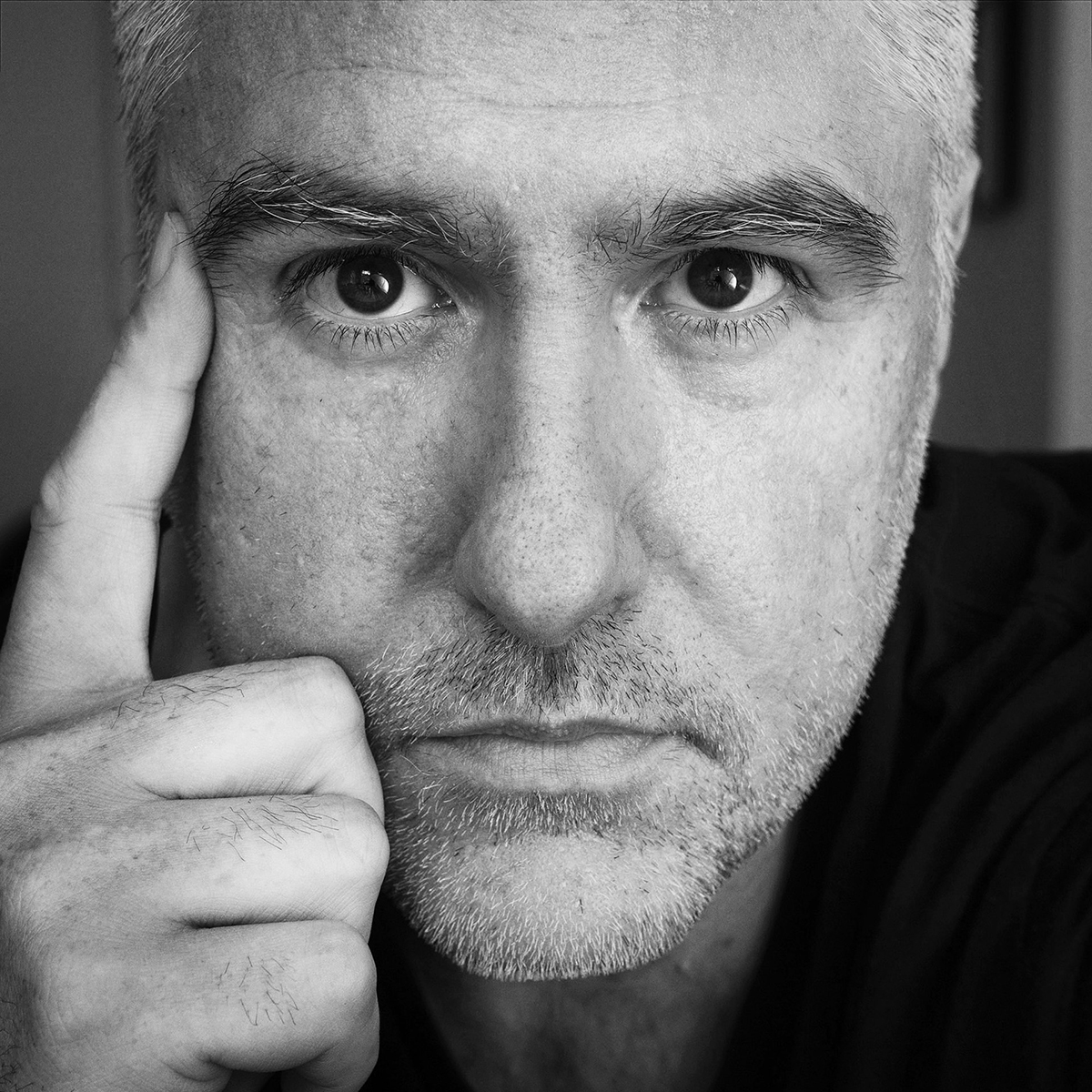

Luxury entrepreneur Binith Shah with LUX Senior Contirbuting Editor Maria Sukkar

Luxury entrepreneur Binith Shah had a vision: to create the most luxurious duvets in the world, using environmentally-friendly methods, for use by the most discerning clients. LUX Senior Contributing Editor Maria Sukkar speaks with Shah about the nature of luxury, how to create a best-in-class product optimised for private jets, premium residences and yachts, and what makes a happy Eider duck.

Maria Sukkar: The word UMŌ evokes warmth, comfort, and softness, while also carrying a poetic quality that heightens sensory experiences – much like the French use parfum to describe an ice cream flavour. What led you to choose UMŌ Paris as the name for your brand?

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

Binith Shah: I’ve always been enamoured with the French culture and my heart and background are in bespoke fashion, couture, and luxury. I also love Japan: how everything that the Japanese do is precise, thoughtful, and simple. Umō is the Japanese word for down, so I just combined the essence of both and decided that UMŌ Paris would be the brand.

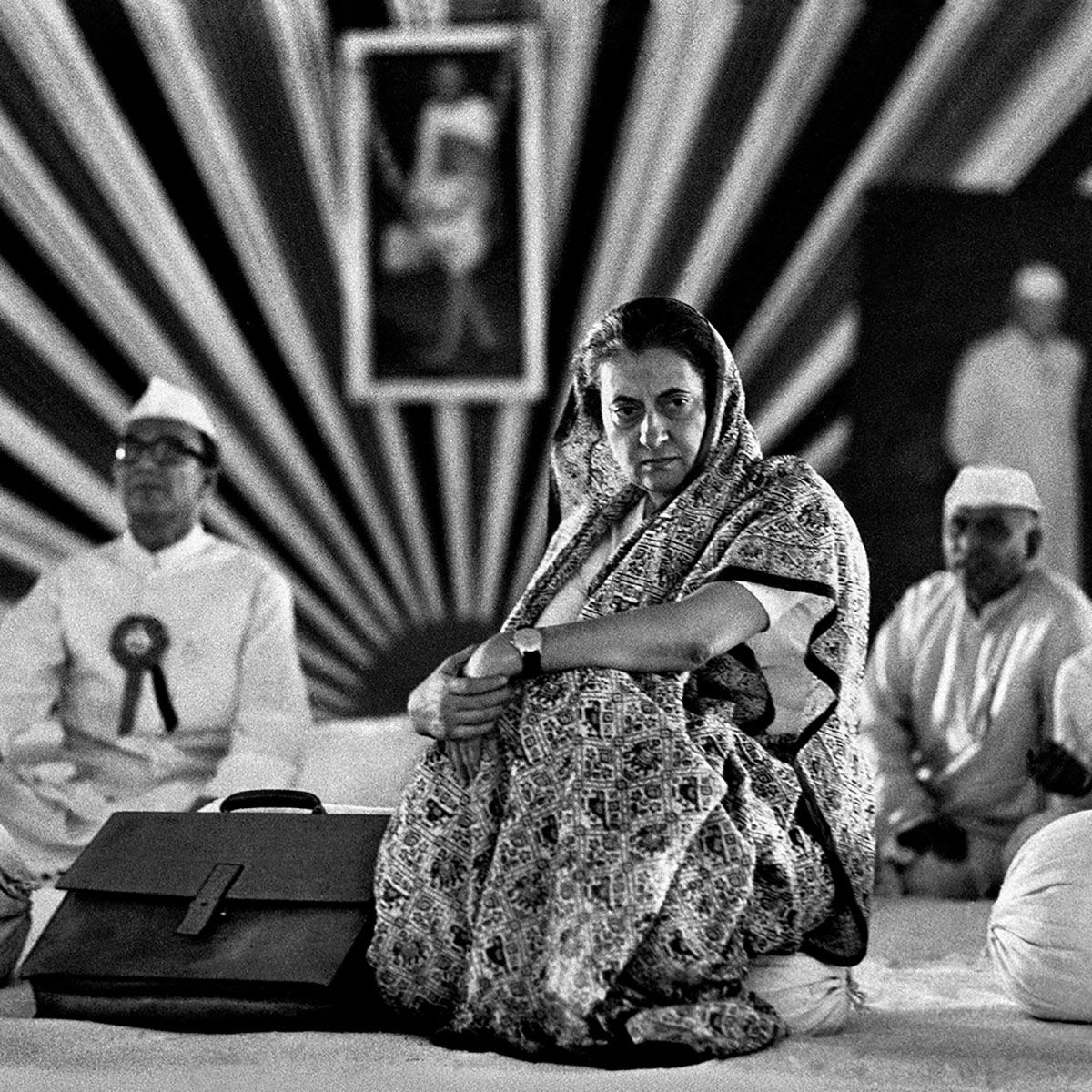

‘I learned the importance of prioritising the craftsmen, because without them, there is no business’ – Binith Shah

MS: Do you think exposure to diverse cultures and communities drives discovery?

BS: I was born in Kenya, raised in Seattle, met my wife in New York, lived in Florence for 12 years in between a year and London, then shifted to LA the last 12 years! My father was also a curious entrepreneur whose passion led into dealing in oriental rugs, which evolved into one of the largest carpet showrooms in Seattle. It fascinated me that he would travel to Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal and return with stories of the craftsmen and artisans who would spend months or even a year to create just one rug for his showroom. Community is a huge part of how I think about business.

MS: It’s similar for me – I’m originally Lebanese with family scattered across the world, including my mother and brother in Beirut and my sister in Dubai. What led you into the creative industries?

Read more: A conversation with architect Thomas Croft

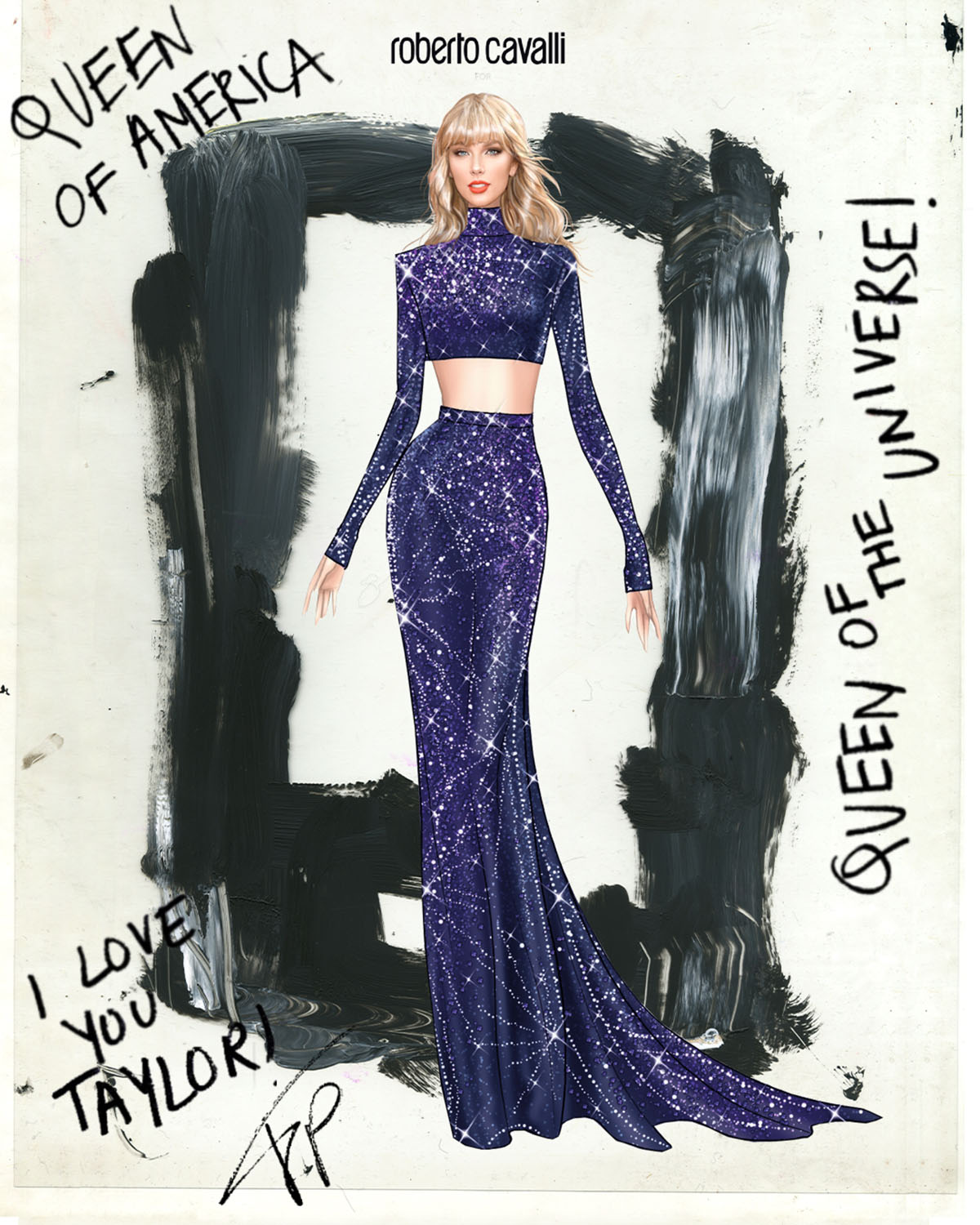

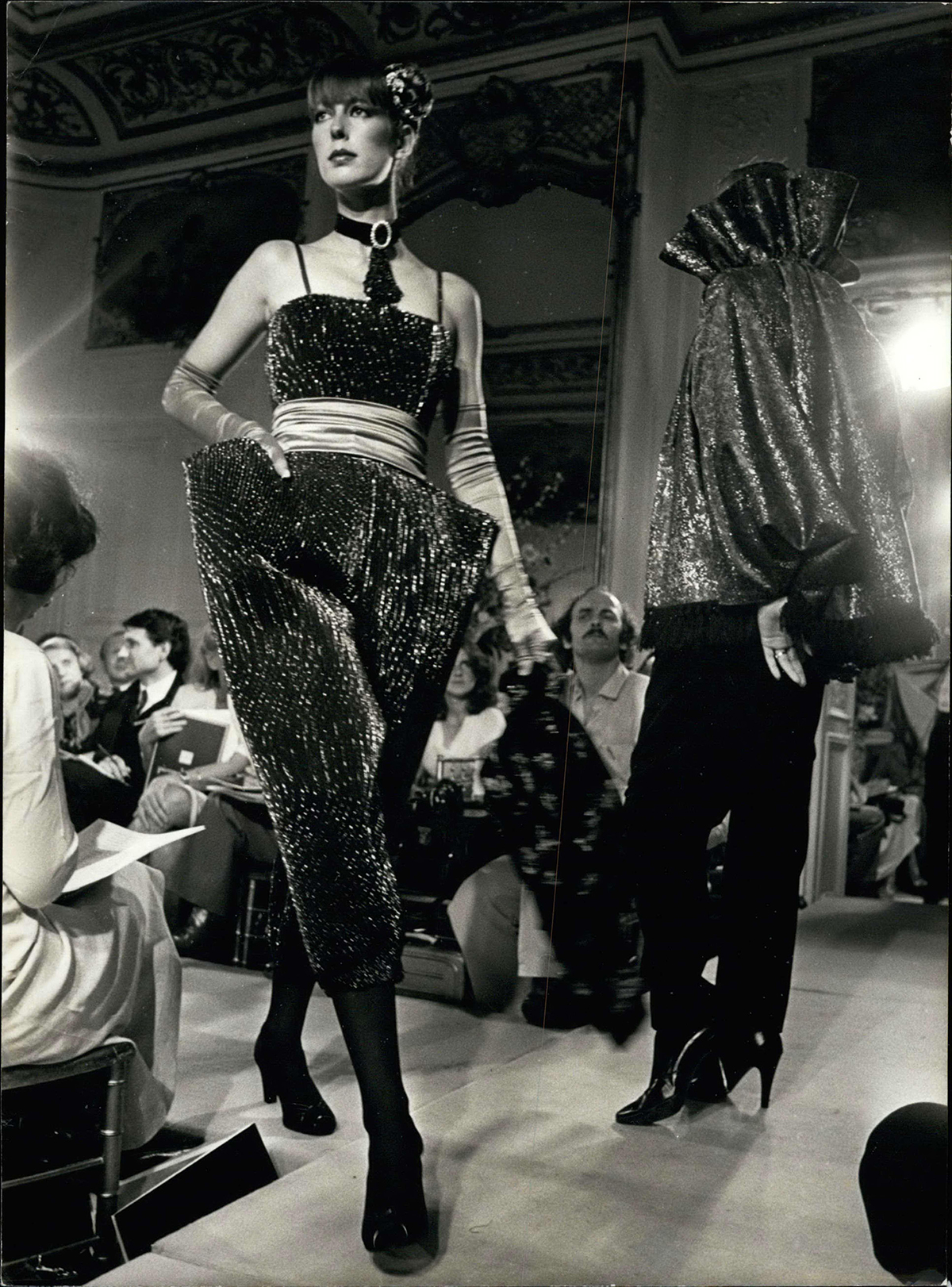

BS: My journey really began when I met my wife, Elizabeth, when she was a top designer for Armani, Sonia Rykiel and Ungaro. I moved to New York to join her, and we went on to create a very high-end luxury shoe and handbag business. Our philosophy was to differentiate ourselves from other brands with bespoke offerings, so we developed a 3D foot scanner, which would take hundreds of intricate measurements of our clients’ feet, customise a last, and manufacture a pair of shoes in a matter of weeks, versus a minimum of six months.

We launched Rickard Shah in the September issue of American Vogue and immediately received significant A-list celebrity customers who were keen to invest in footwear tailored to their individual style and needs. As a result, we were very fortunate to have one of the largest luxury conglomerates among our primary investors. We were highly successful, with long waitlists, eventually disrupted by the financial crisis of 2008. Our bijou atelier was forced to close, and I learned the importance of prioritising the craftsmen, because without them, there is no business.

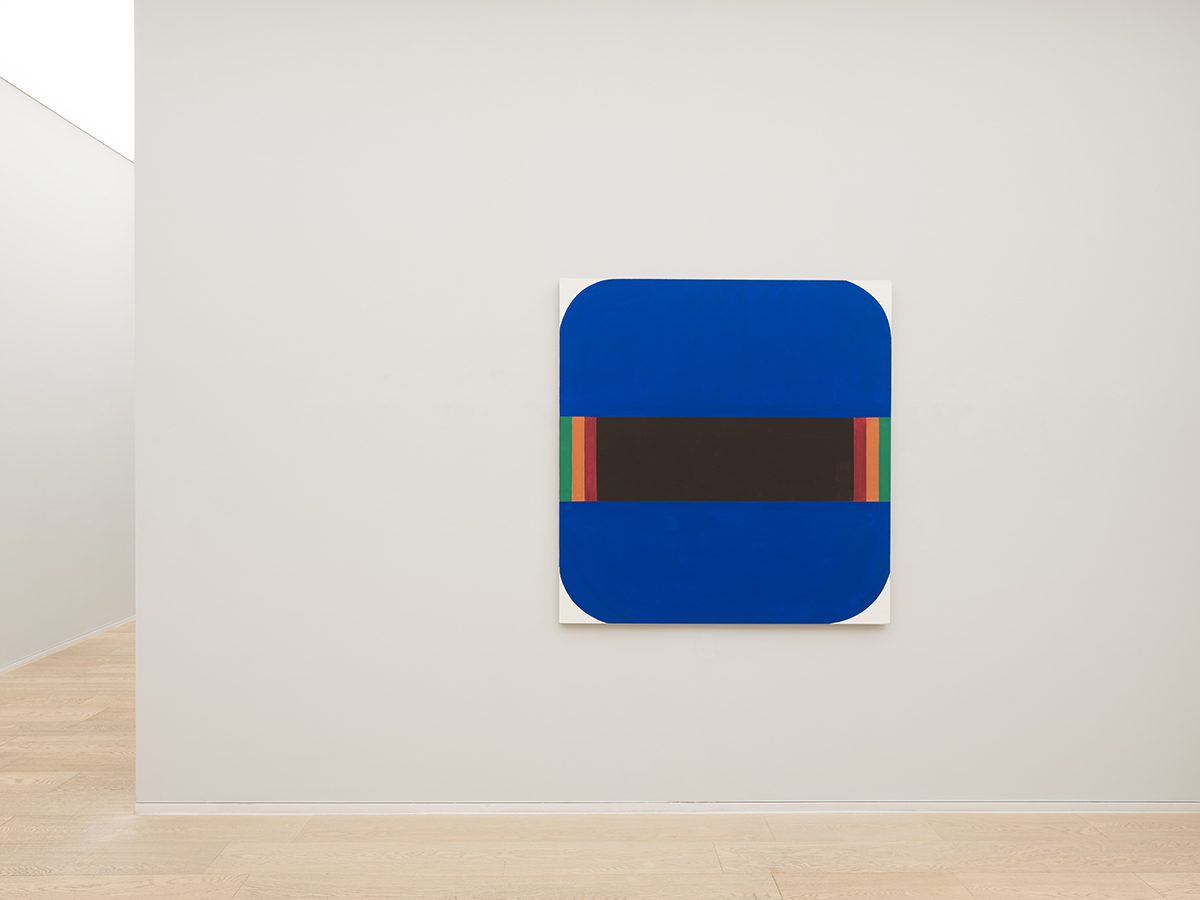

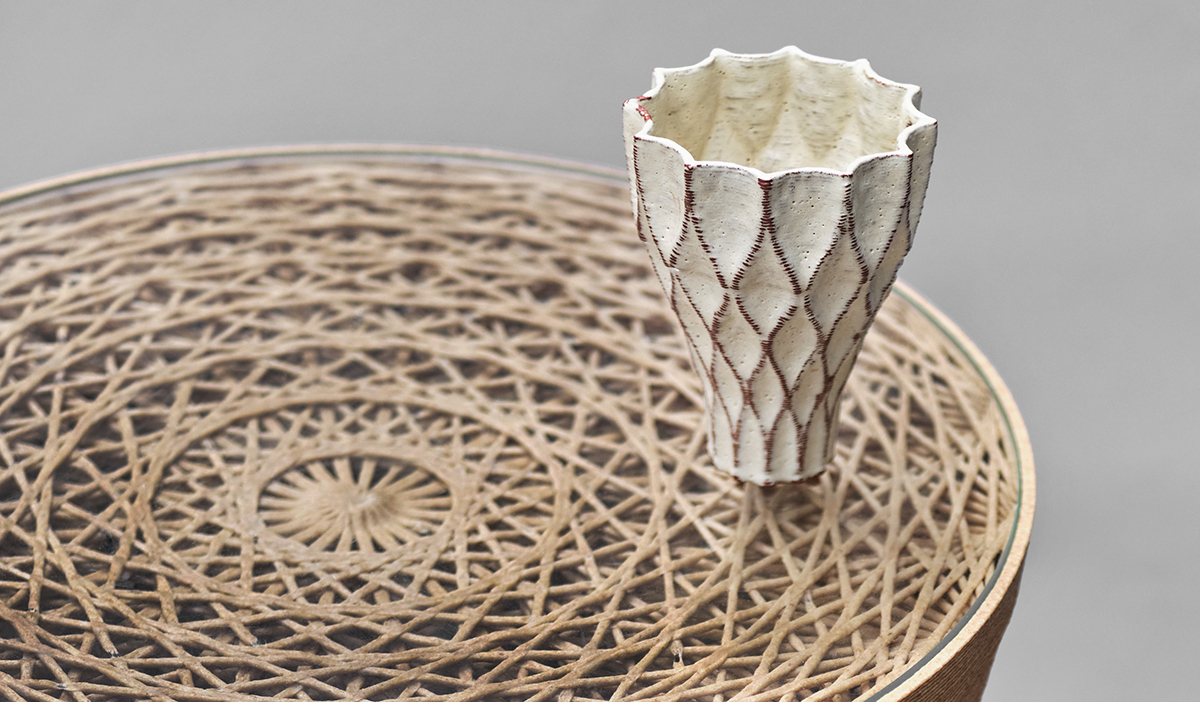

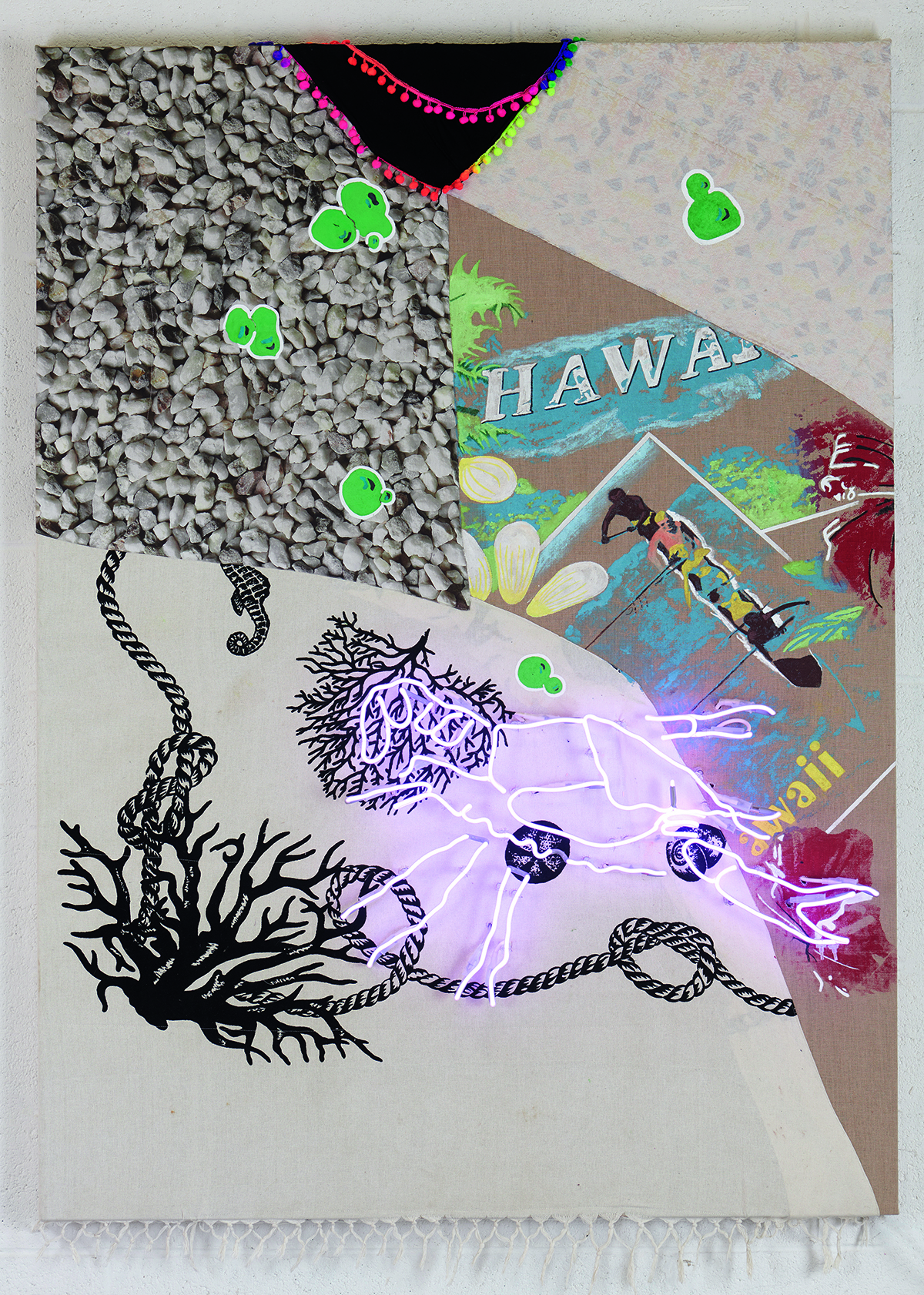

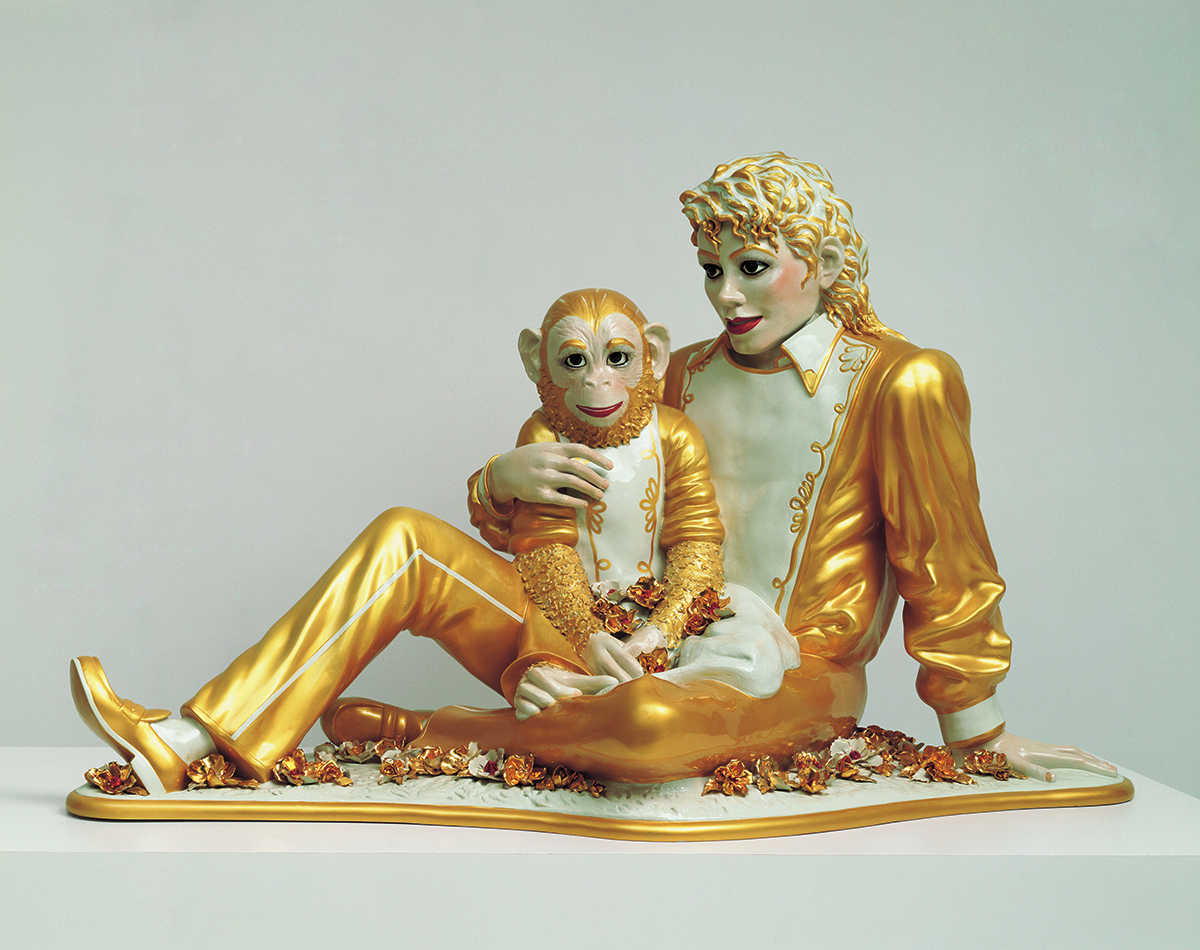

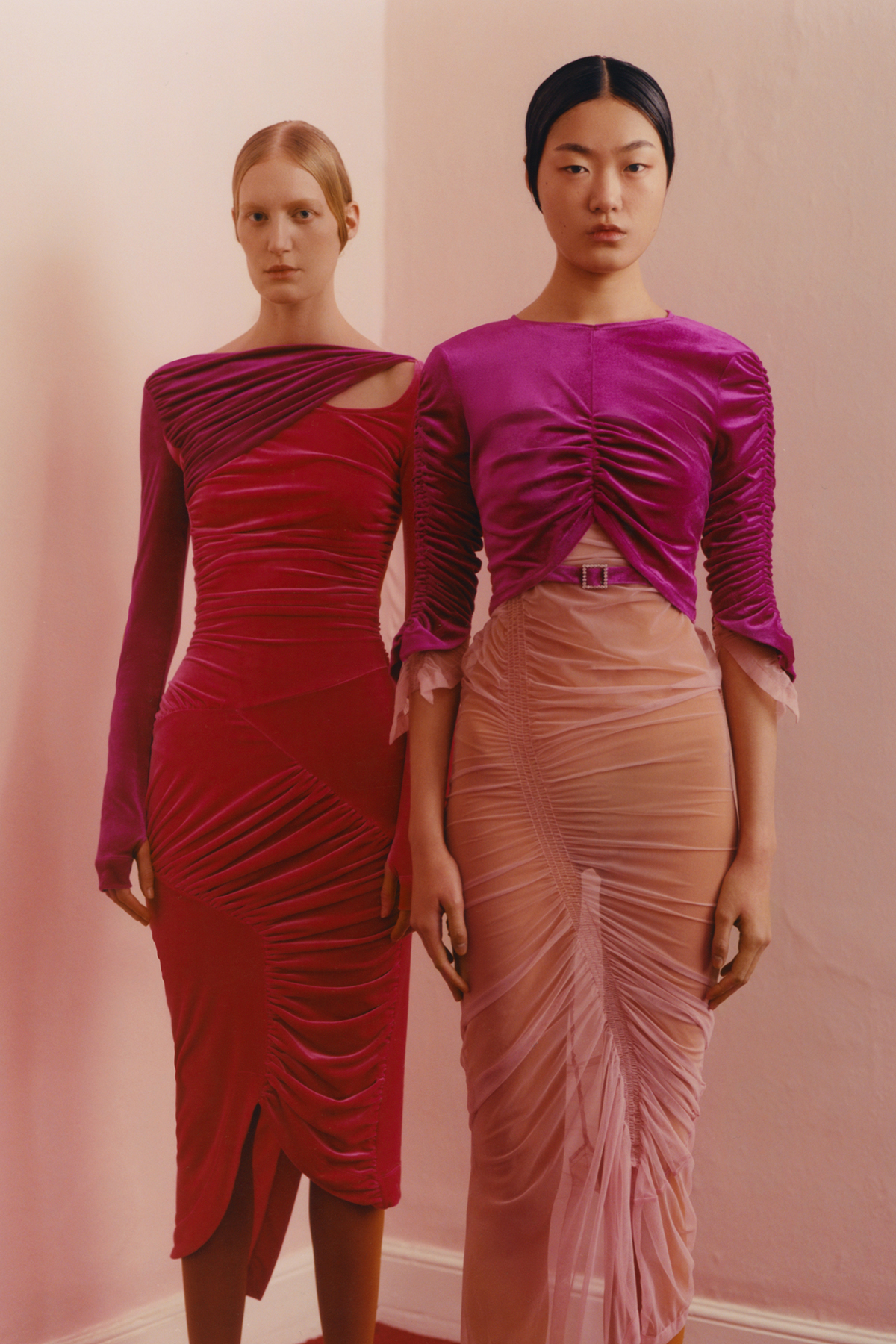

Each luxury duvet features UMŌ Paris’ signature embroidery of the Eider duck wing

MS: As an entrepreneur how did you move into sustainable luxury?

BS: It happened while we were in London during the financial crisis, with a Knightsbridge flagship boutique and our young daughter. We felt the current method of tanning leather accessories was not as environmentally friendly as it could be and sought solutions. We conceived of a sustainable solution, which led us to create a company in Florence called Green Dot, which produced the very first biodegradable and sustainable TPU. TPU is a soft resin, which is the key component of sneaker soles or flip-flops. Logistically, it made sense for our family to relocate to the US, where our resin was manufactured.

Read more: BMW M760e long-term review

We successfully exited Green Dot following three-years’ of founding the start-up. Through that venture, this confirmed we could deliver a sustainable luxury product, which became a stepping-stone to into various new chapters and ultimately led me to where we are now.

MS: How did you develop a concept for sustainable luxury duvets?

BS: A sabbatical afforded me the opportunity to consider deeply what I had learned and what was important to me. This was creating a bespoke product that was both ultra-luxurious and sustainable, serving a niche need that had not been addressed. I read about the hypoallergenic and thermal properties of Eider down and could not understand why no one was working with this magical material in an elevated manner.

‘With UMŌ Paris it is about the craftsmen and the caretakers of a beautiful Eider duck sanctuary’ – Binith Shah

My preliminary research indicated there were cottage industries in Iceland, Norway, and Canada creating niche duvet brands. I tested everything. I am passionate about supporting craftsmen, artisans, sustainability and collaborating with incredible people. This time, I wanted to create something focused, where I would have full control over the mission and the message. Everything about the story spoke to a sustainable luxury venture.

MS: Where did you see the sweet spot for you, as an entrepreneur?

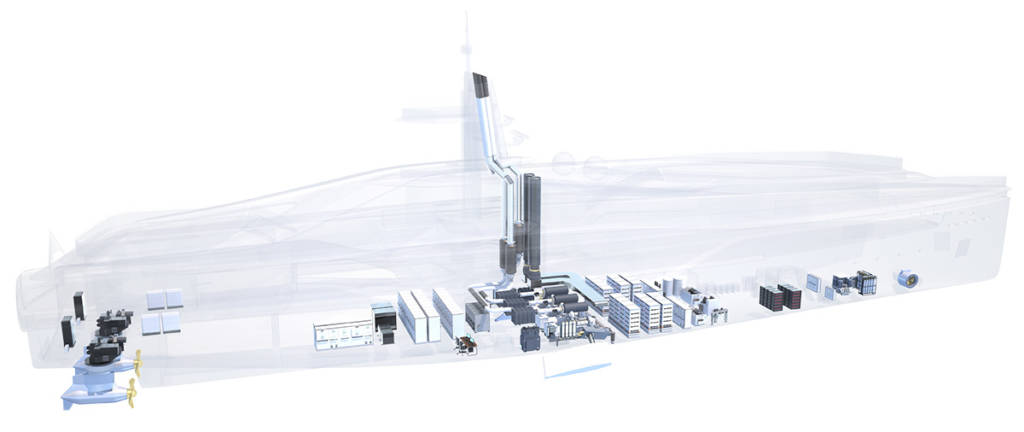

BS: The way I have always worked is to think ‘Where is the need? Where is the pain?’ If you have neither, you cannot achieve it, someone bigger will do it better. When I incorporated UMŌ Paris, I partnered with a private aviation specialist, Jay McGrath. I knew that ultra-affluent clients expect an unparalleled experience and they need optimum sleep in their aircraft cabin.

Read more: Omega CEO Raynald Aeschlimann on the watch industry

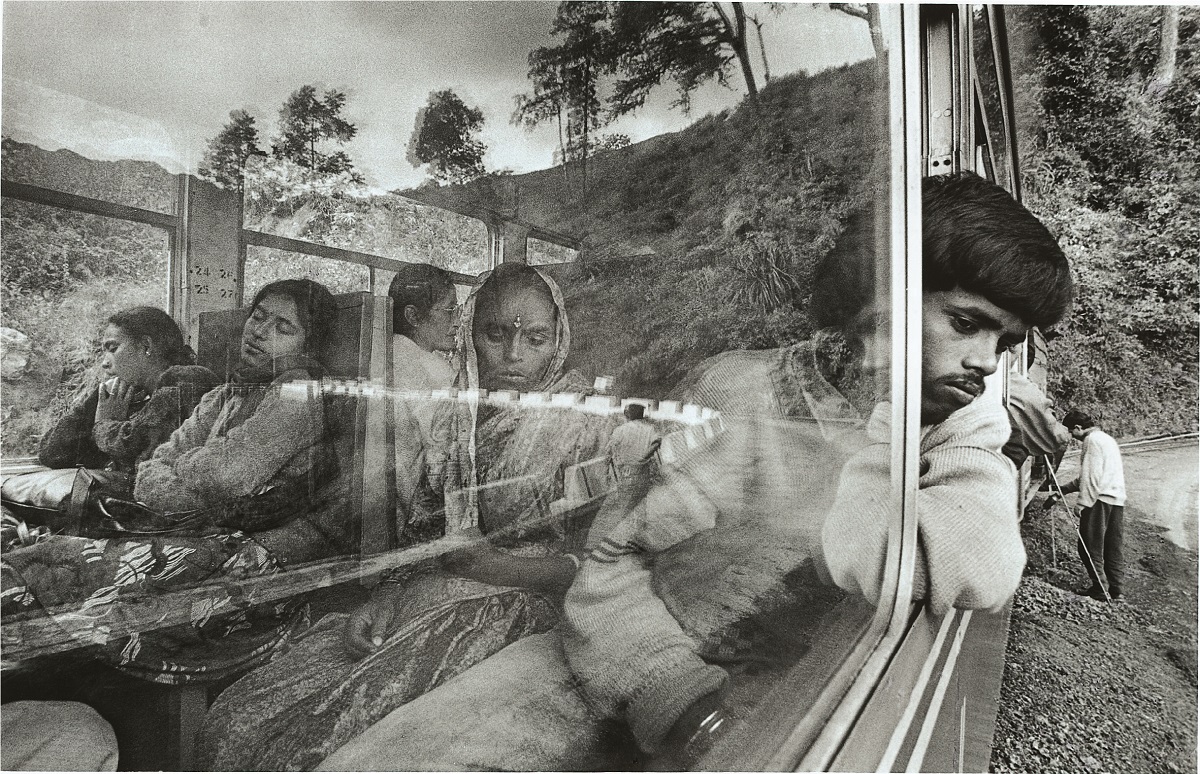

With limited storage space and a pressurised cabin, size and weight are the pain points. These duvets can be stowed on your G650 without requiring extra equipment for vacuum packing. Further, for every kilo saved in weight, there is a saving of around 15,000 tons of carbon over a jet’s lifetime. We launched our Aviator collection with one of the largest jet charter companies, and immediately accessed a network of demand from 270 jets.

We also created our hand-crafted Fjord and Maison lines for premium residences and yachts. A luxury lifestyle brand is about creating a meaningful experience, it is not like queuing for a bag on Rodeo Drive. Once experiencing our duvets, our clients describe a cloud-like sensation and a quality of sleep they’ve never had before. They share that experience with their family and friends, and the brand is growing by word-of-mouth.

‘Located in Iceland’s Fljótin Skagafjörður on the edge of the Arctic Circle on the Tröllaskagi Peninsula, this protected land has been in the stewardship of one family for 80 years, over three generations’ – Binith Shah

MS: It is a great model, how do you frame that experience?

BS: We start the journey with the narrative. Then it is shared authentically through influential advocates. You could be at a dinner, and someone mentions their discovery of this amazing product out there, which is not only in an extremely limited supply, but also champions sustainability through artisans and community.

MS: What is it about Iceland in particular that resonated with you?

BS: I had to identify the most premium Eider down. With UMŌ Paris it is about the craftsmen and the caretakers of a beautiful Eider duck sanctuary. In Iceland, the eider ducks have been protected by the Icelandic Government for well over a century. Sanctuary owners have experience and proven business models, monitoring and reporting duck numbers to the government.

I researched the Icelandic sanctuary owners and selected a sanctuary that was in synch with my ethos. Located in Iceland’s Fljótin Skagafjörður on the edge of the Arctic Circle on the Tröllaskagi Peninsula, this protected land has been in the stewardship of one family for 80 years, over three generations. The young owner invited me on a site visit, loved our story, understood the potential markets, and immediately partnered.

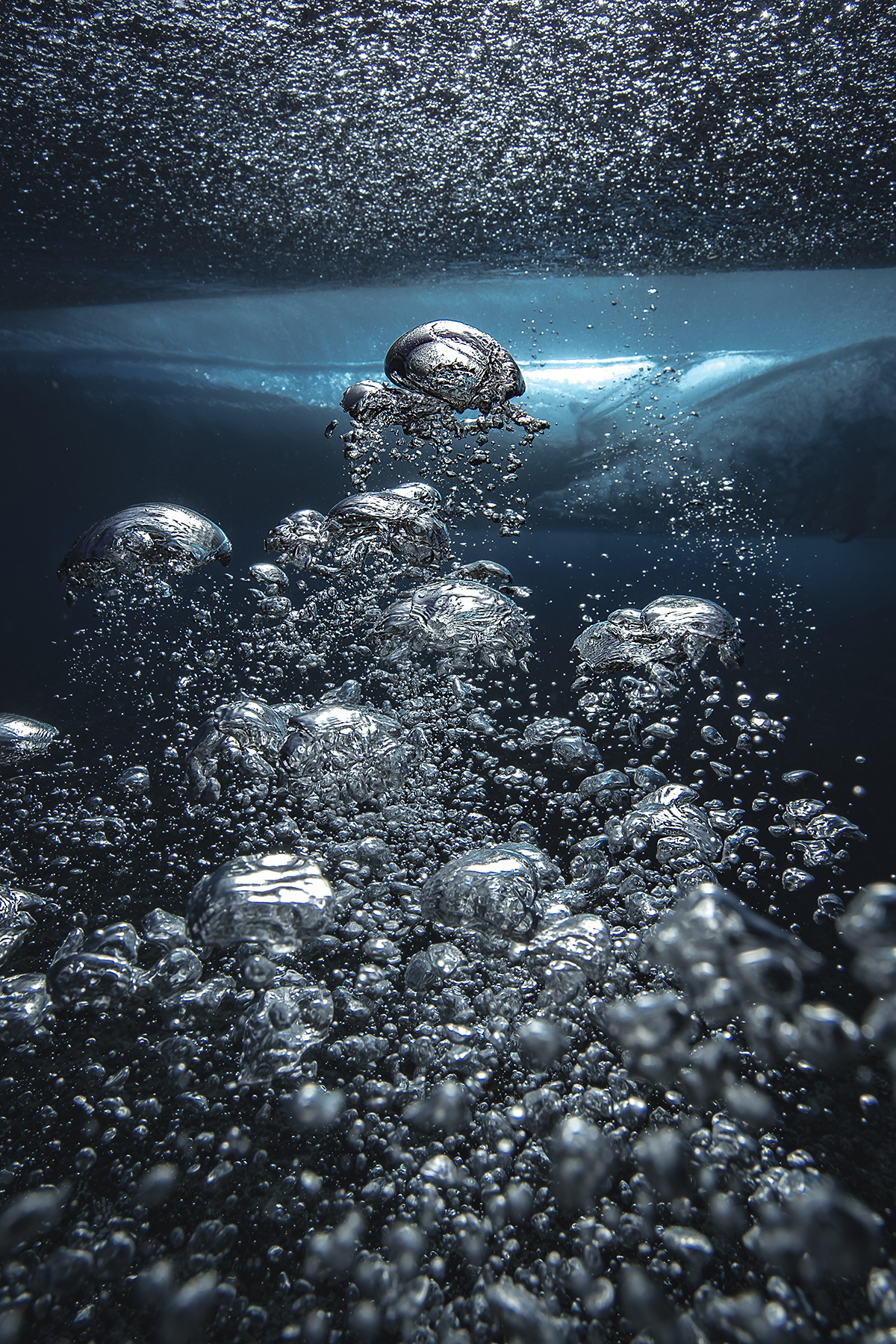

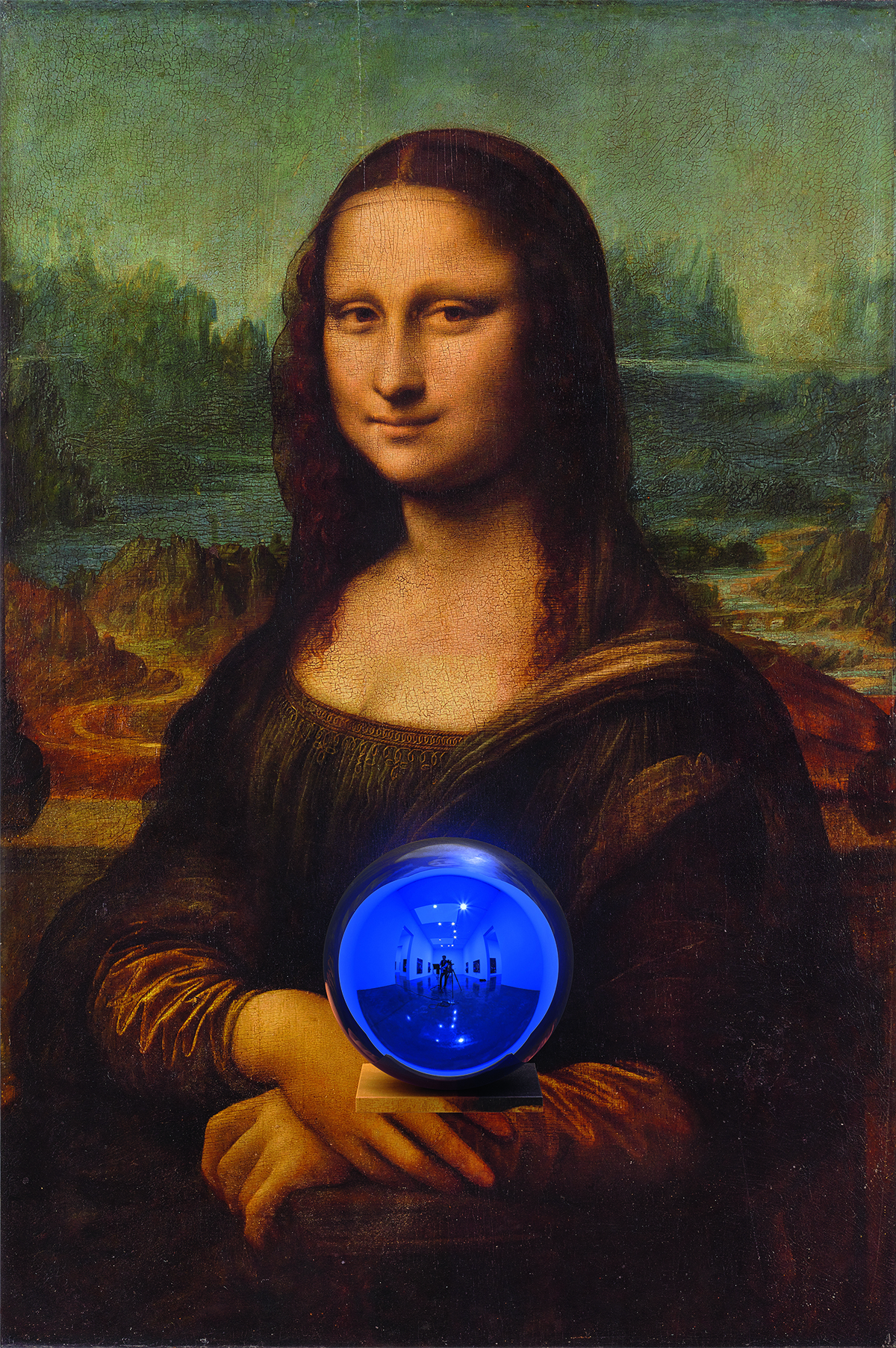

UMŌ Paris duvets are filled with the premium and sustainable Eider down from Iceland

MS: Where did you come up with the idea of UMŌ Paris as a responsible luxury brand?

BS: Through our network, Elizabeth and I found a fifth generation, 150-year-old certified B Corp atelier in Chablis, France. Upon presenting our business model to the owner, we were aligned in our mission to create a rare sustainable luxury duvet.

MS: How did UMŌ Paris show rarity and authenticity from the get-go?

BS: The meticulous and labour-intensive process results in an annual total yield of only an estimated 8,900 pounds/4,000 kilograms worldwide. At current values, this makes Eider down around 6 times rarer than rough mined diamonds! We use 6-8% of the global supply and our production is limited to 350-500 duvets annually. Unlike our competitors, we only use Pure Arctic Eiderdown, the lighter, finer down. Our duvet requires 65 hours to make, from gathering the down to transporting it and producing the finished duvet. Our product is born wild, never farmed.

Read more: Simon de Pury interviews Olafur Eliasson

MS: Given the precision and care involved, can you truly say this process is cruelty-free?

BS: Absolutely. We collect the nest at the right time, when the eggs laid are nearly hatched and don’t need the incubation of the nest. The skilled caretakers gently pick up the Eider duck, gather the nest, handpick-out the down, and then put the duck back on the nest for the final days before the eggs hatch. The method in which most goose and duck down are normally processed involves the birds being live-plucked up to 17 times, then finally slaughtered for food.

That’s the process for the world’s premier brands’ luxury down jackets and that method consumes around 270 million kilos of down a year versus only 4,000 kilos of Eider down. Our process is completely cruelty-free, gentle and kind. The fledglings leave their nests, immediately return to the sea for approximately 11 months, until they return to the sanctuary to moult their down into the nests and lay their eggs. The ducks’ number is monitored by the sanctuary caretakers.

‘Eider down is 100% hypoallergenic with no feathers or quills present. It is ultra-light and maintains your body temperature while you’re sleeping’ – Binith Shah

Mother Nature plays a very key role in this natural product. Weather conditions, sea levels and other natural phenomena all contribute to the annual yield – and underscores the need for preservation. That is all part of the impressive story. We also donate 10% of profits back to the conservationists to continue preservation and education.

MS: What is UMŌ Paris’ point of difference, compared with other niche brands using eider down?

BS: Our differentiator is that we only use Pure Arctic Eiderdown, partner with a Certified B-Corporation atelier, and design with intent. Competitors fill their duvets with components that are 90% eiderdown, 10% goose down. However, they still charge for 100% Eiderdown, so Eiderdown is often used as a marketing play. Our sustainable process also assures quality because eider down is 100% hypoallergenic with no feathers or quills present. It is ultra-light and maintains your body temperature while you’re sleeping. This is achieved also because of thoughtful design.

Normal duvets are subdivided into square baffles, to hold in place the loose down and eventually it slips down into these pockets. Eider down has miniscule hooks so it cannot slip, allowing it to be cohesive and not separate. We designed a series of square baffles across the top end of the duvet slip, then add long vertical channels to allow air to circulate through the length. This open technique maximises airflow, which maintains body temperature.

MS: Where are you on your sustainability journey?

BS: In fact, we’re now in the process of applying for B Corp certification, both to demonstrate transparency that we are using sustainable methods of gathering and to highlight that we are partnered with the B Corp manufacturer in Chablis. There are no guidelines, but we are taking the right steps to acknowledge the sustainability aspect of what we’ve created – which is collaborating to make a positive impact on the community, animals, and the planet.

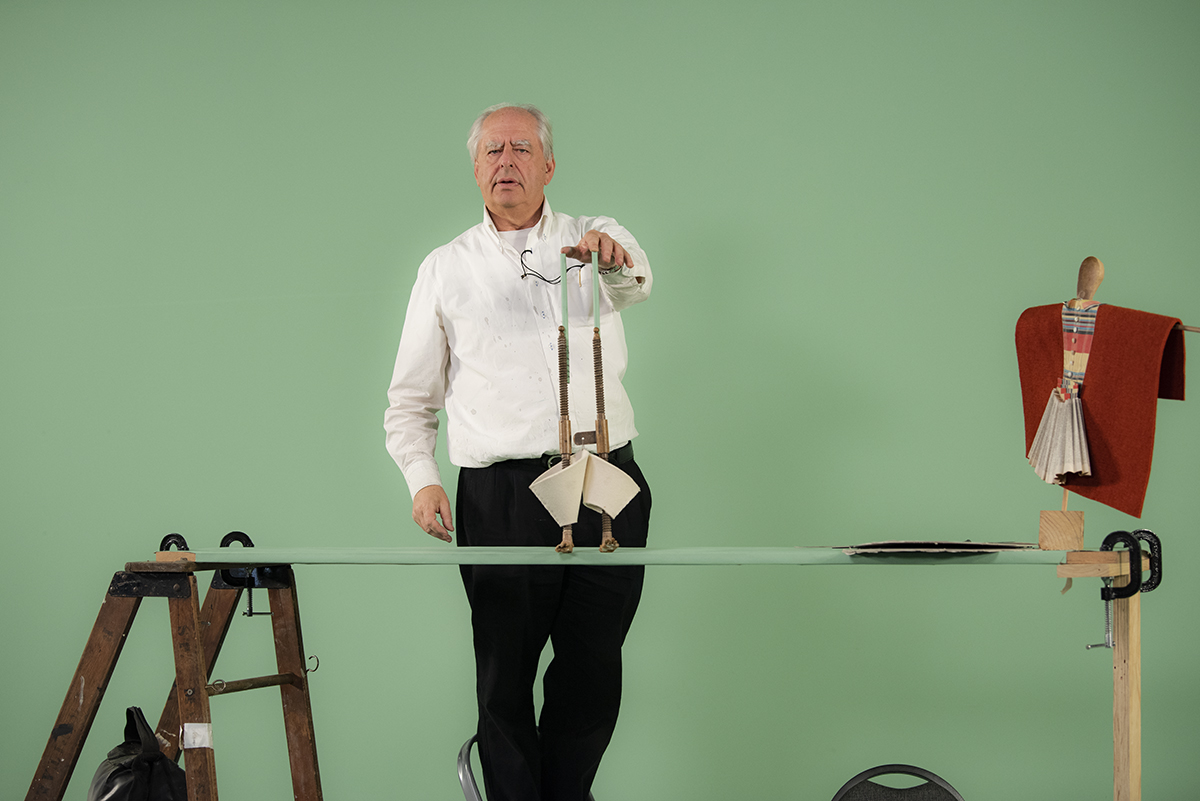

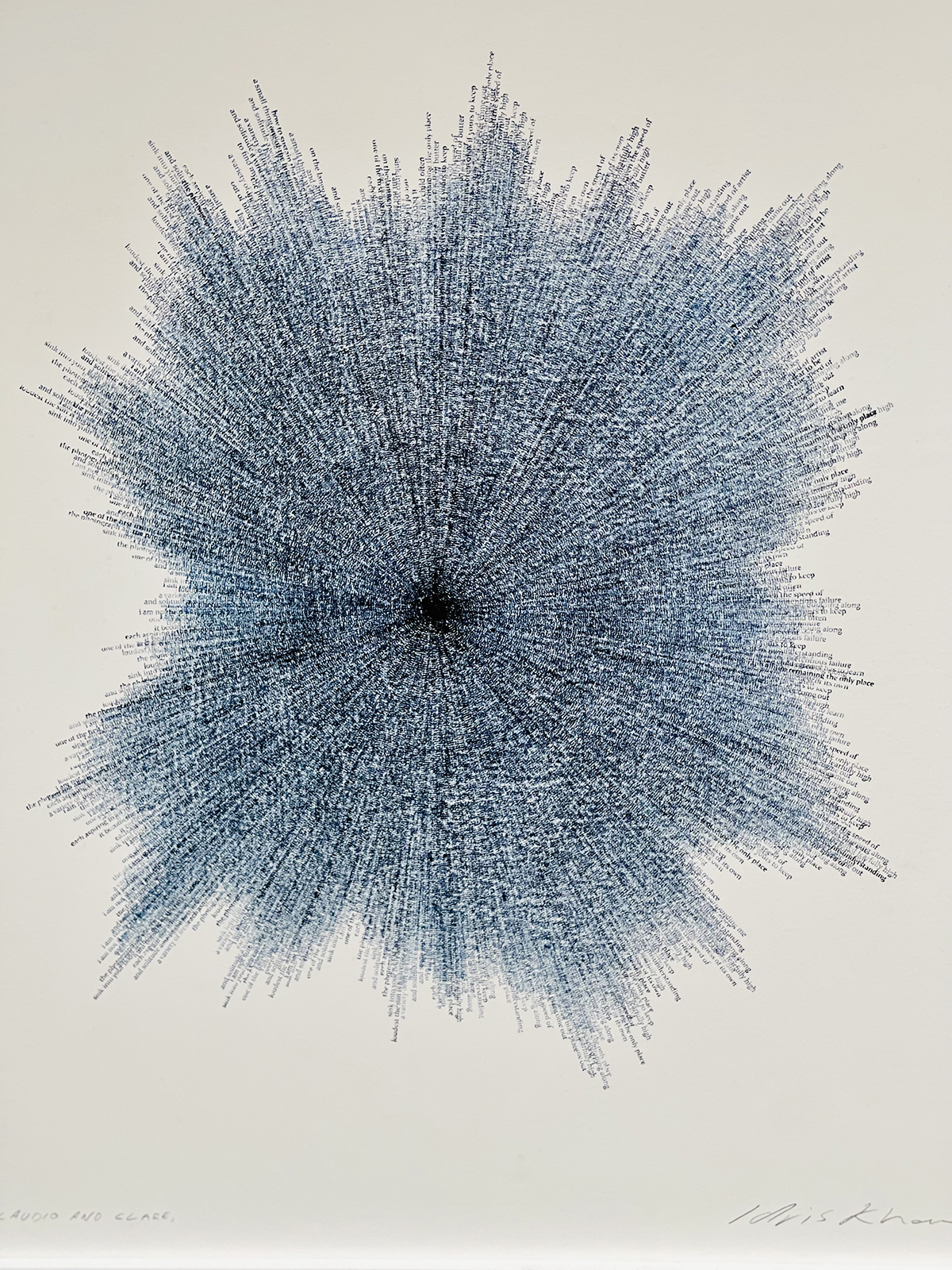

UMŌ Paris’ founder Binith Shah holds his ultra-luxury duvet stuffing

MS: Can you share your vision for enhancing impacts?

BS: We are exploring how we can learn from other industries. For example, when we lived for 12 years in Italy, when it is the season for olive oil harvest, the farmers use a communal press called a frantoia. They tap-in their appointment times, these multi-generational farmers sit chatting during the pressing, families compare oil, colour and qualities. Producers may keep or opt to sell-on their product direct from the press. That’s what we want to do in Iceland. We want to create a communal hub to process the down quicker and pay the sanctuary owners faster. Normally, companies place orders and the sanctuaries are paid 45-90 days later. For us, as soon as our down is ready, we place our bulk order, and we pay for it up-front. Our goal is to take a thought leadership role, where our goal is to secure our allotment and build goodwill, while encouraging the promotion of the sanctuaries and Iceland.

Read more: How collecting unites lovers of wine, art, watches and cars, with Penfolds

MS: Lastly, what do you think about transformational travel, where people can experience their impact throughout the hospitality journey from arrival to venue to departure, subliminally absorbing the values as they sleep under an UMŌ Paris duvet?

BS: There is a shift in luxury travel, where experiences are paramount. Fortunately, our brand is niche and is aligned with the heightened sense of awareness surrounding more transformational travel. The sanctuary is not and will never be a ‘destination’, however, knowing the journey of a product is more and more important to clients. We’re inspired by the adventurers who truly value responsible travel and a novel experience through the fjords in the Arctic rather than sailing their superyacht through the Med in June! We are proud to be part of this important conversation, and that the ultra-affluent are excited to learn more and join us in this journey.

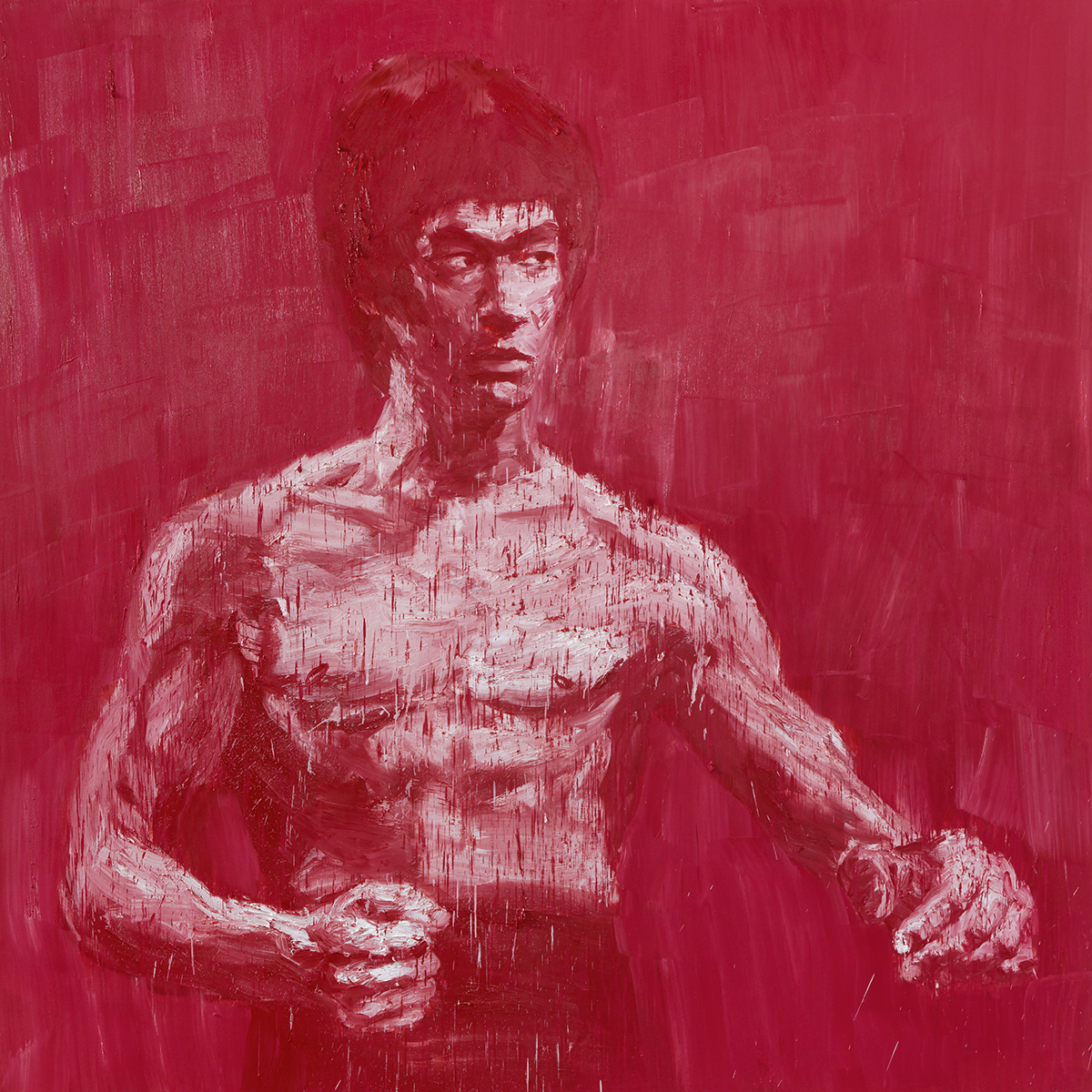

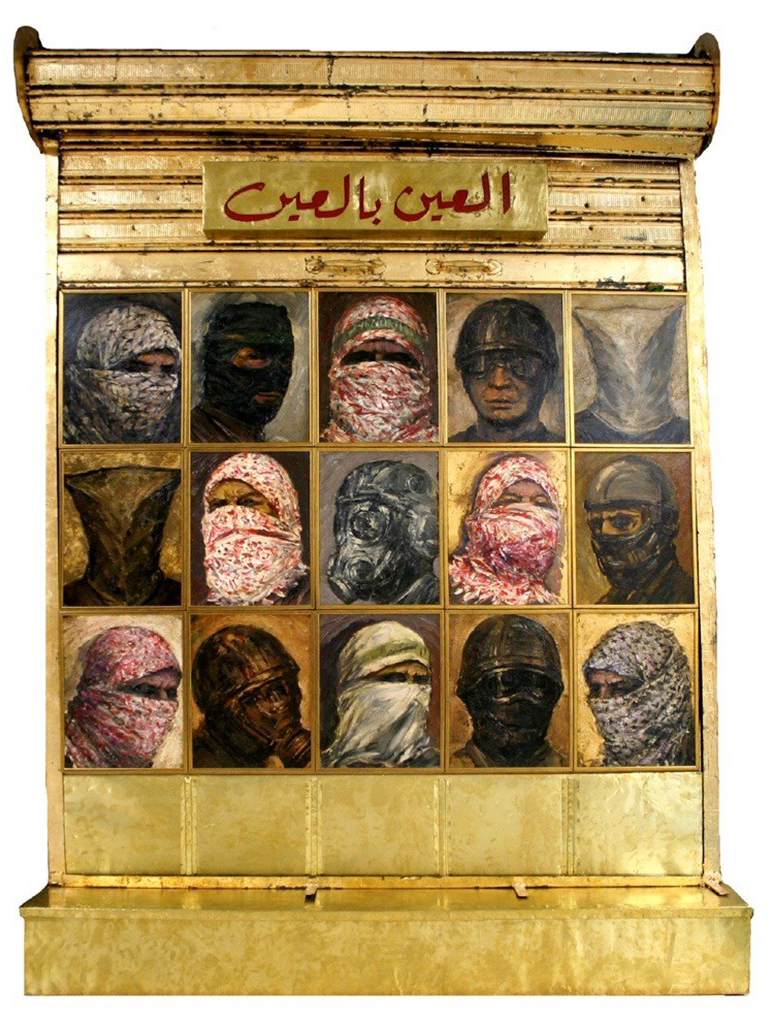

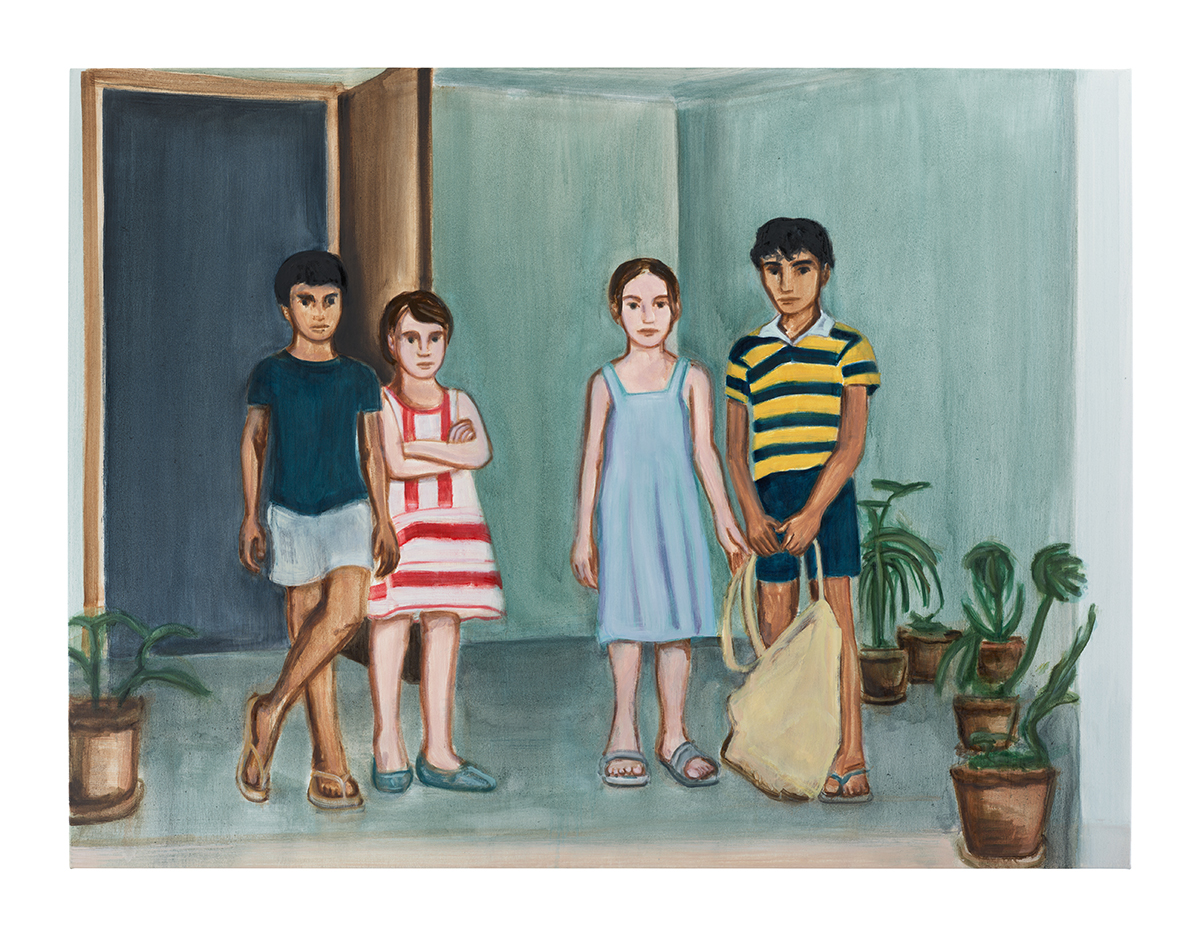

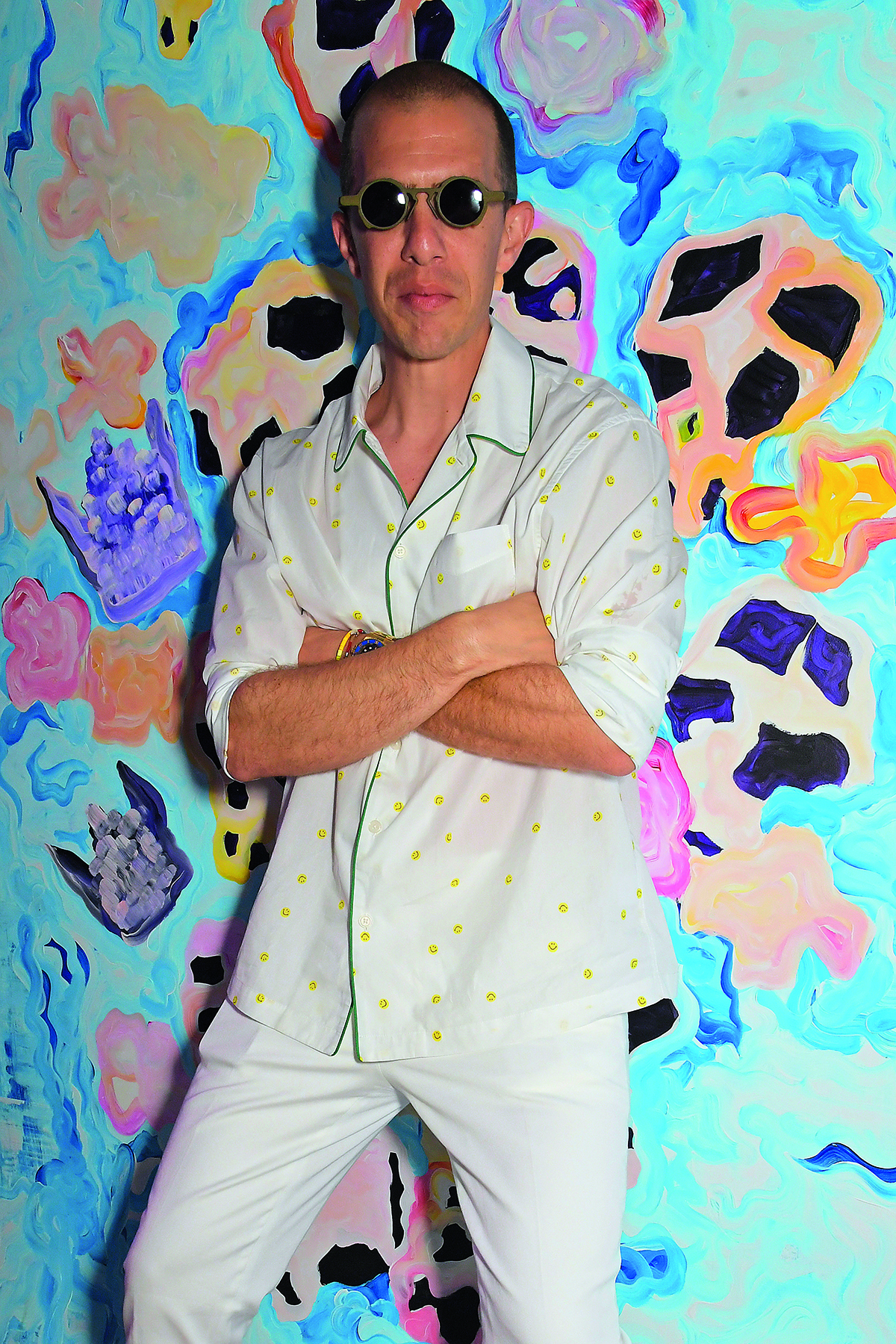

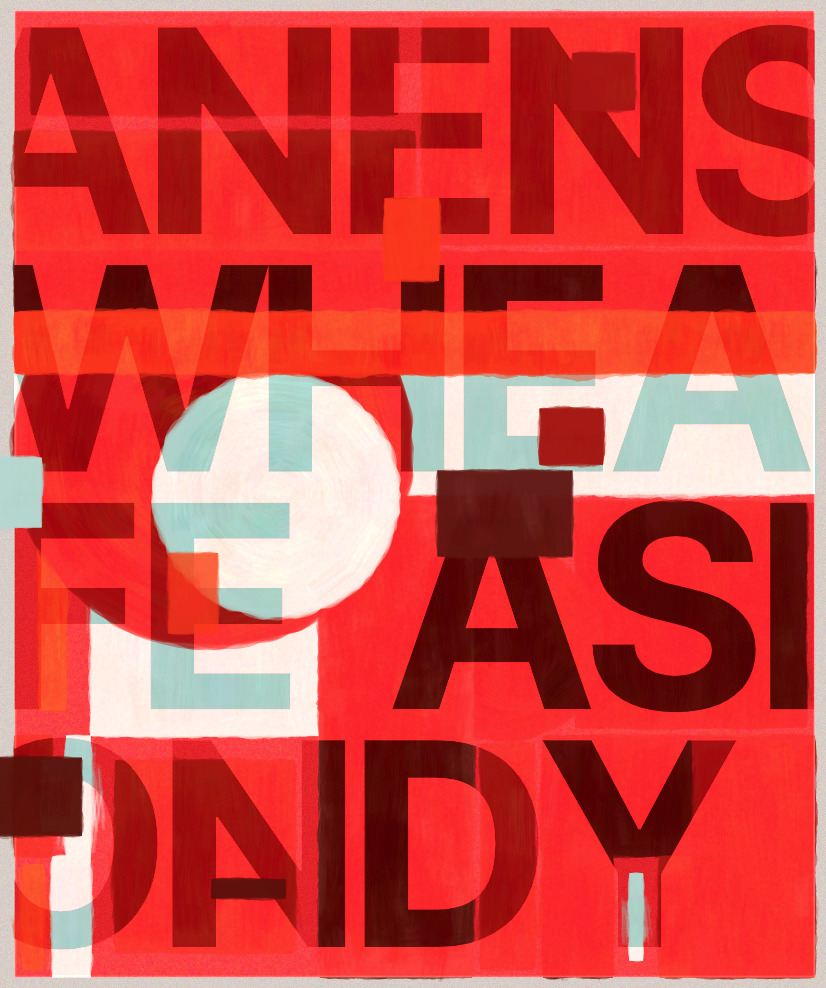

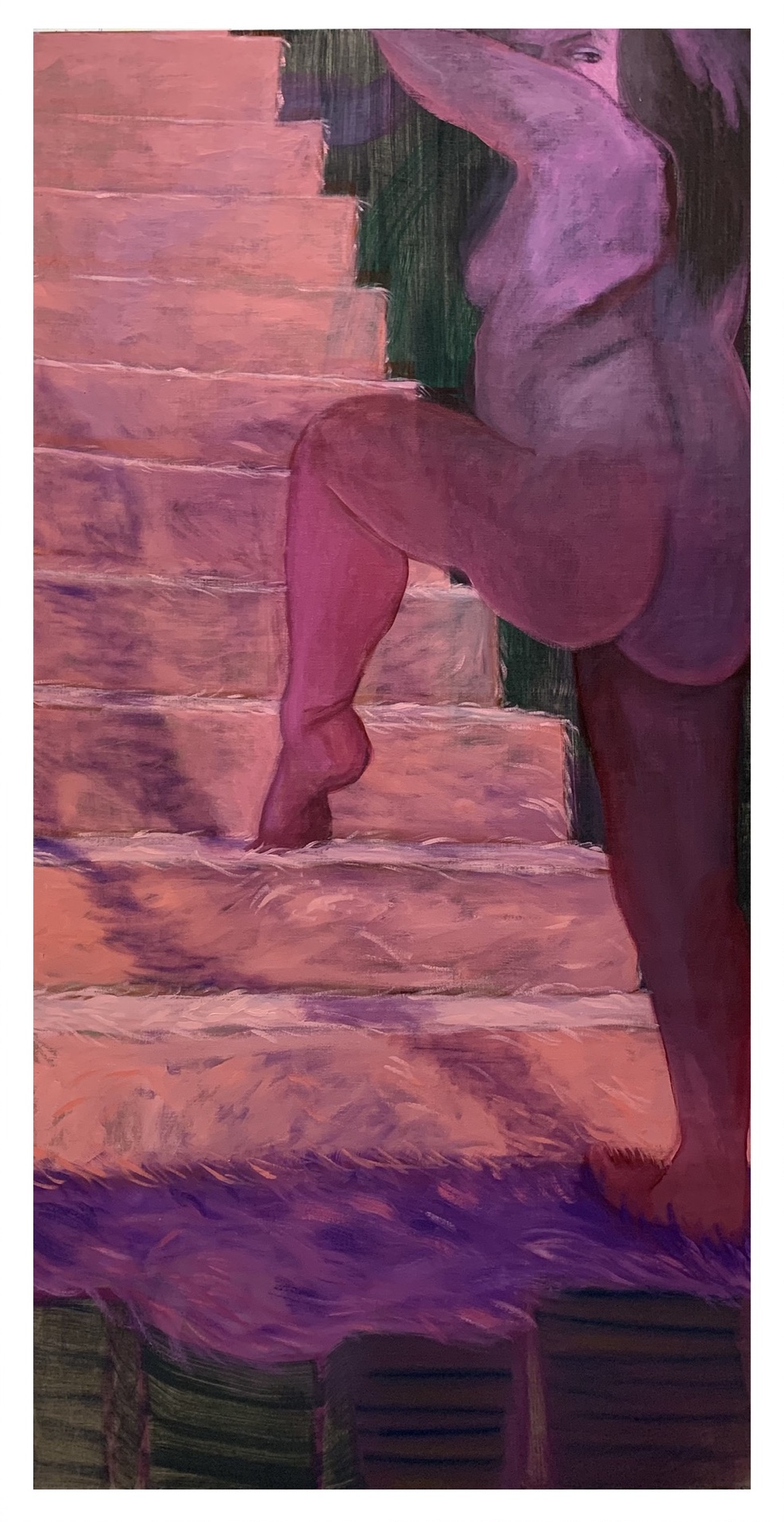

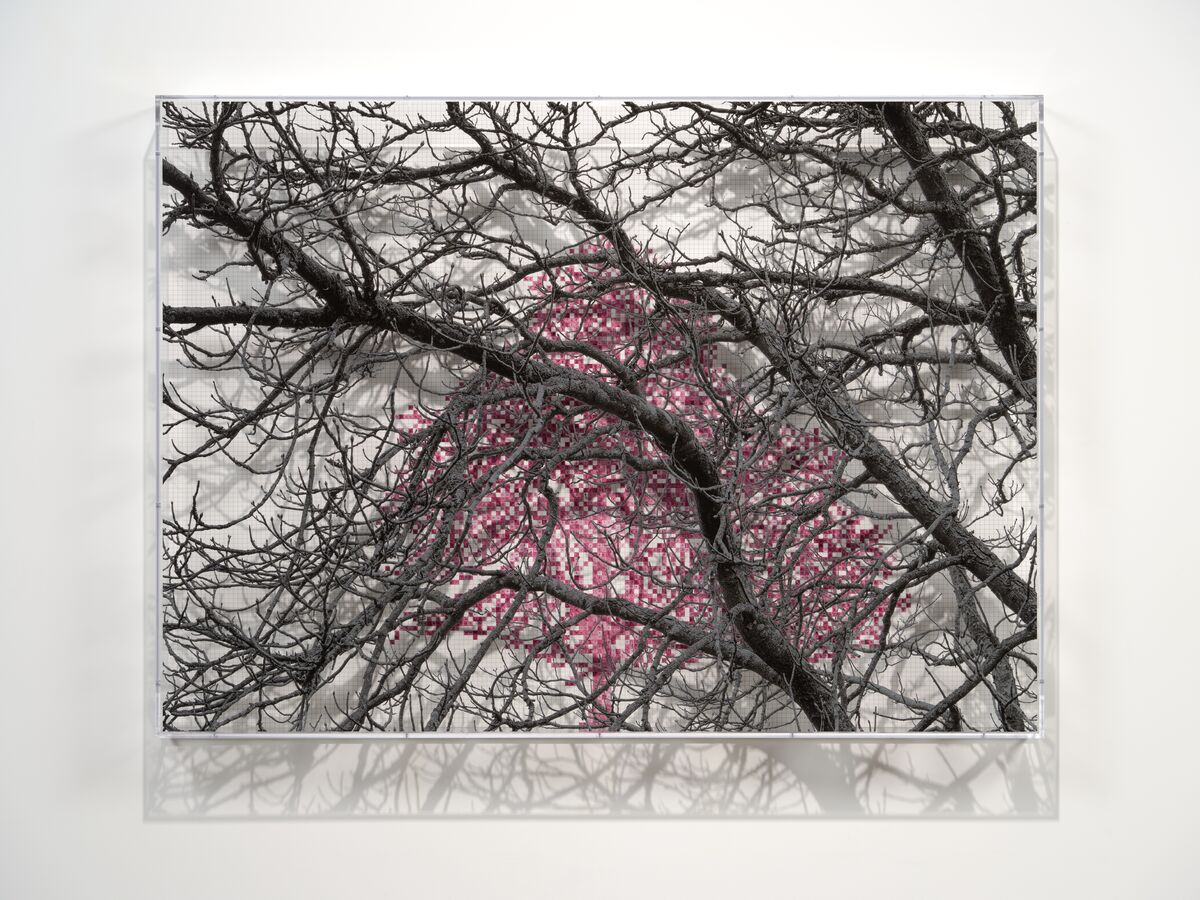

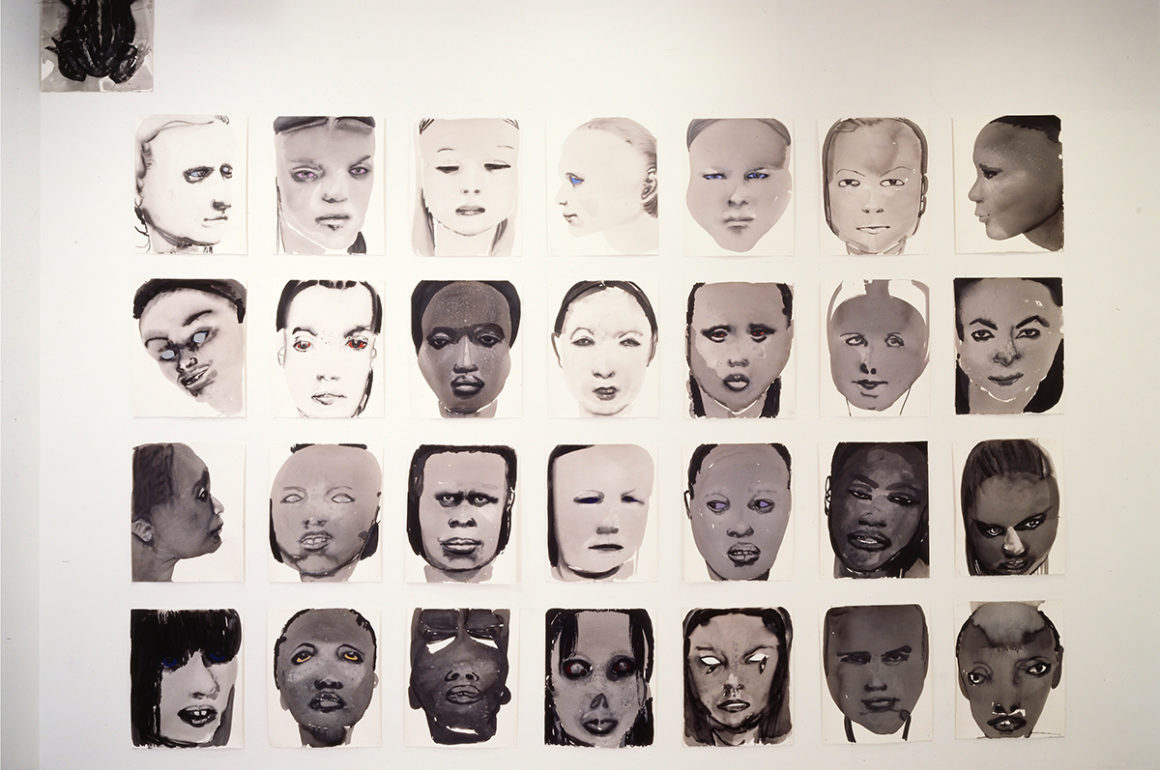

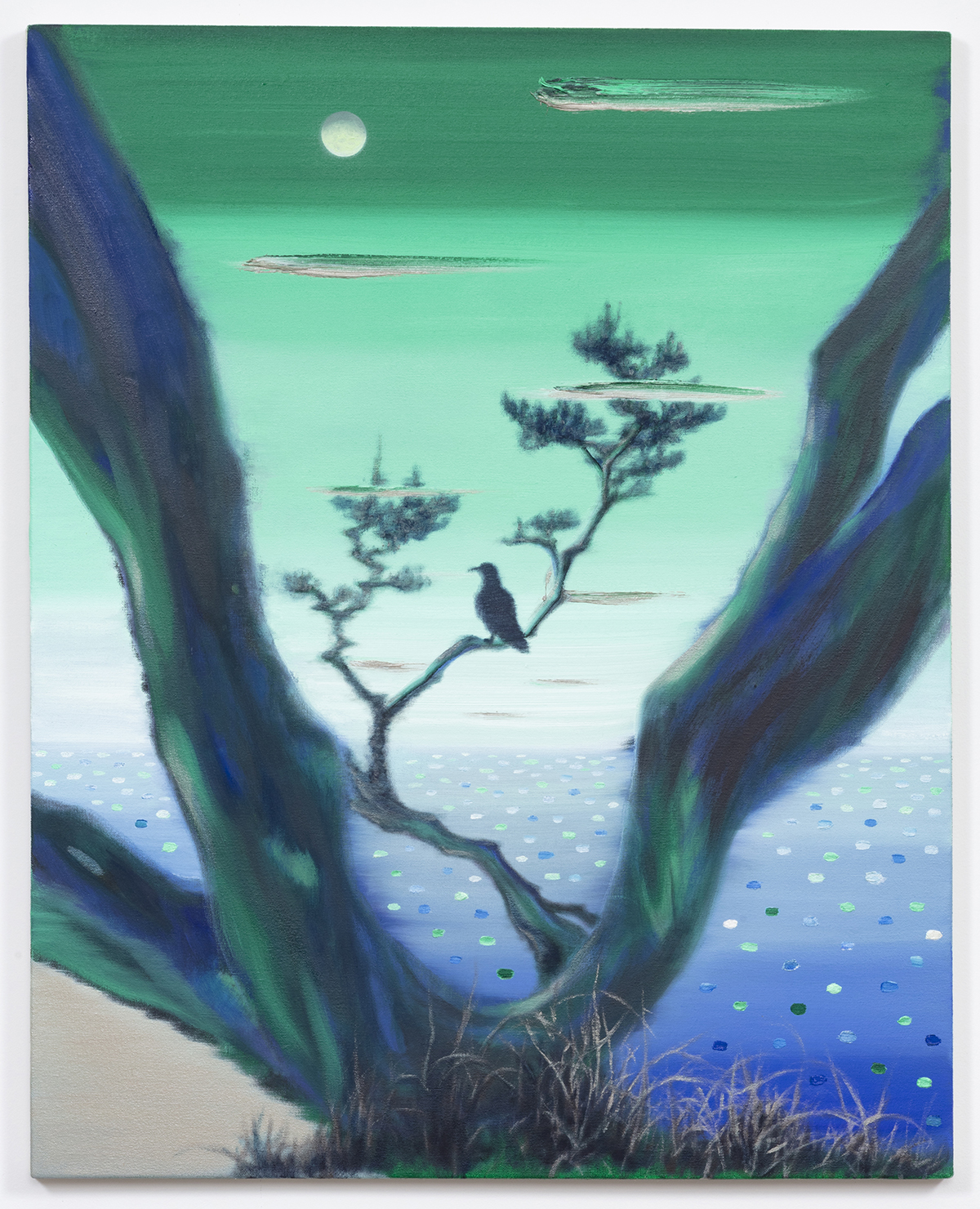

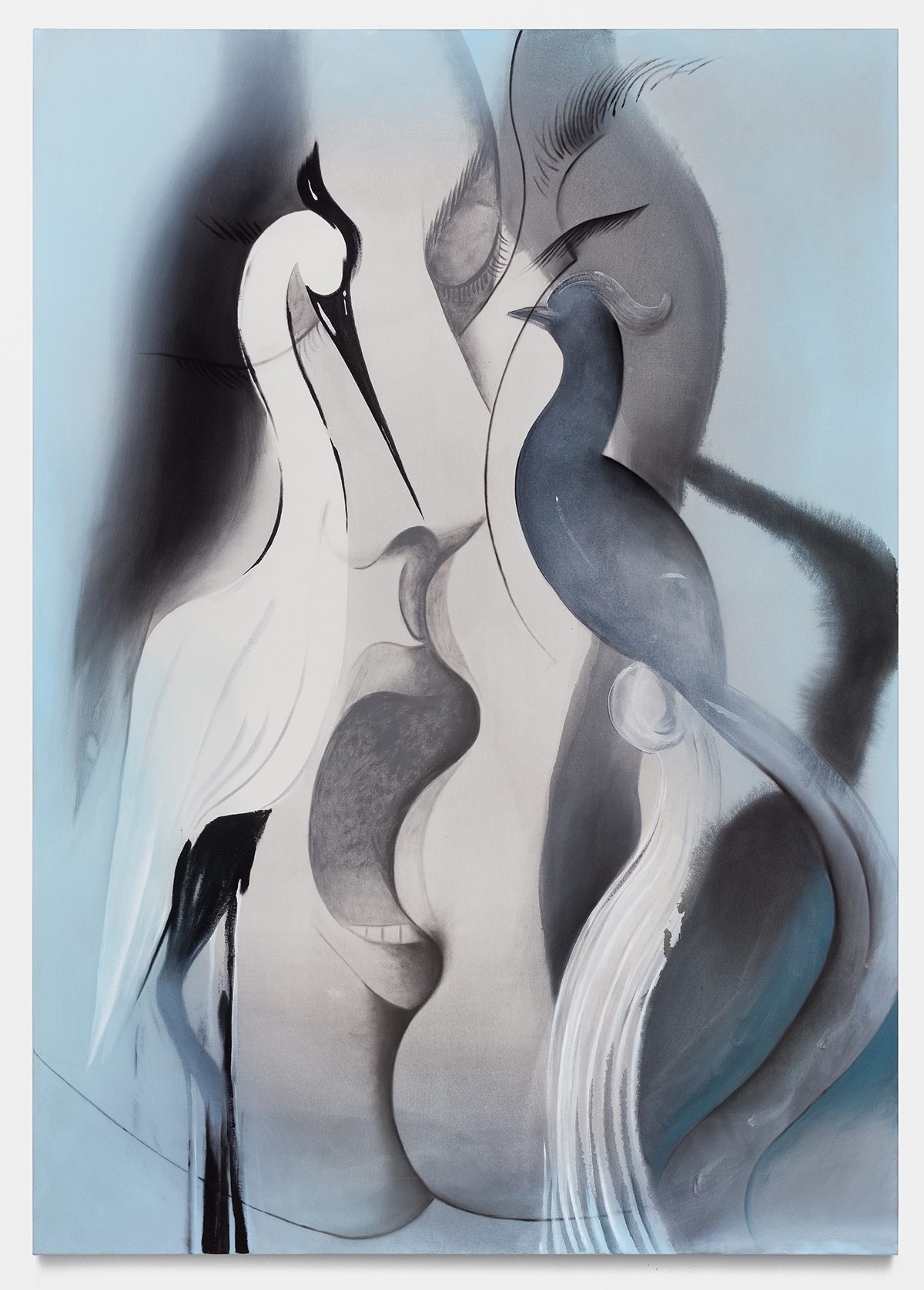

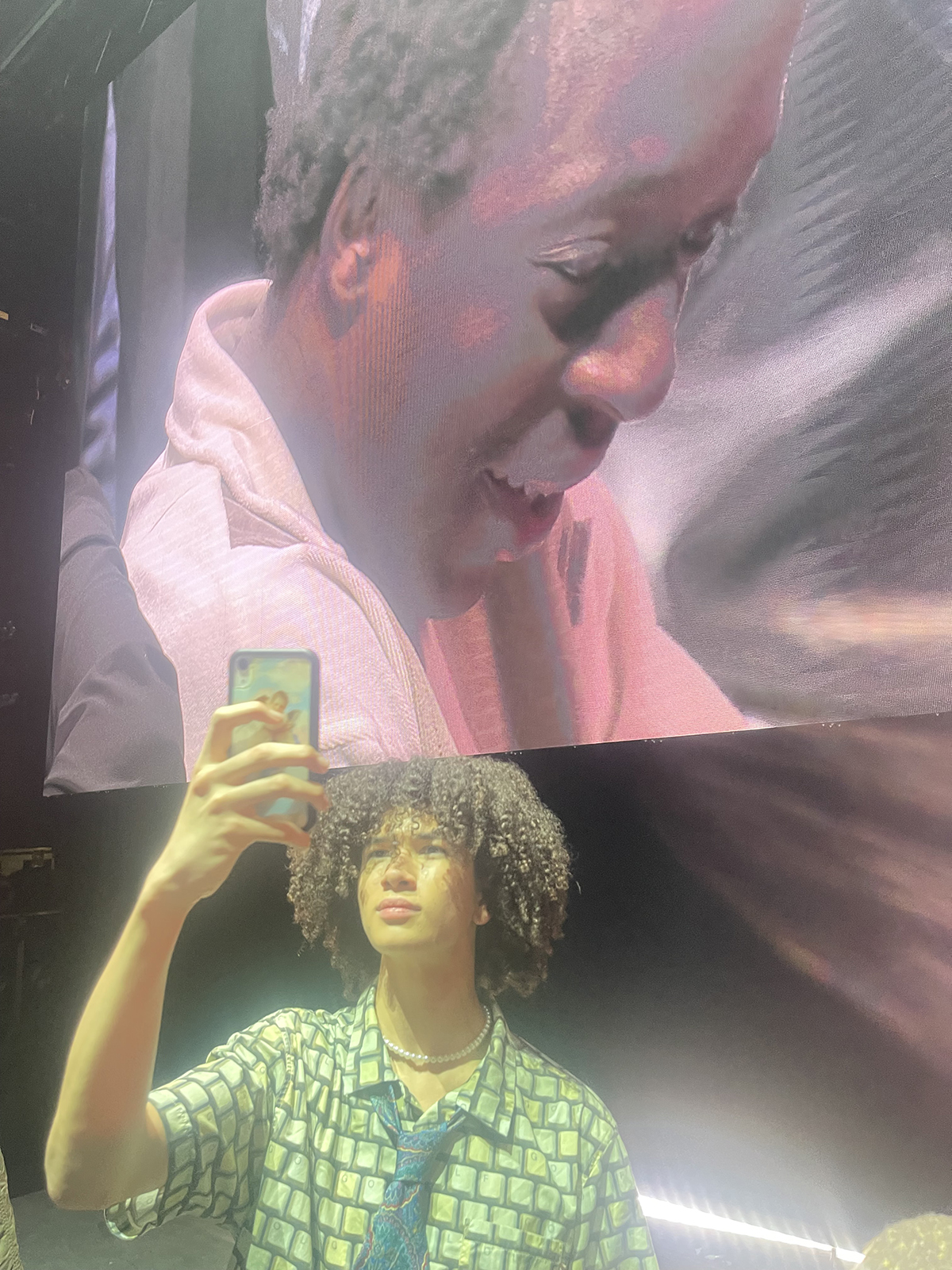

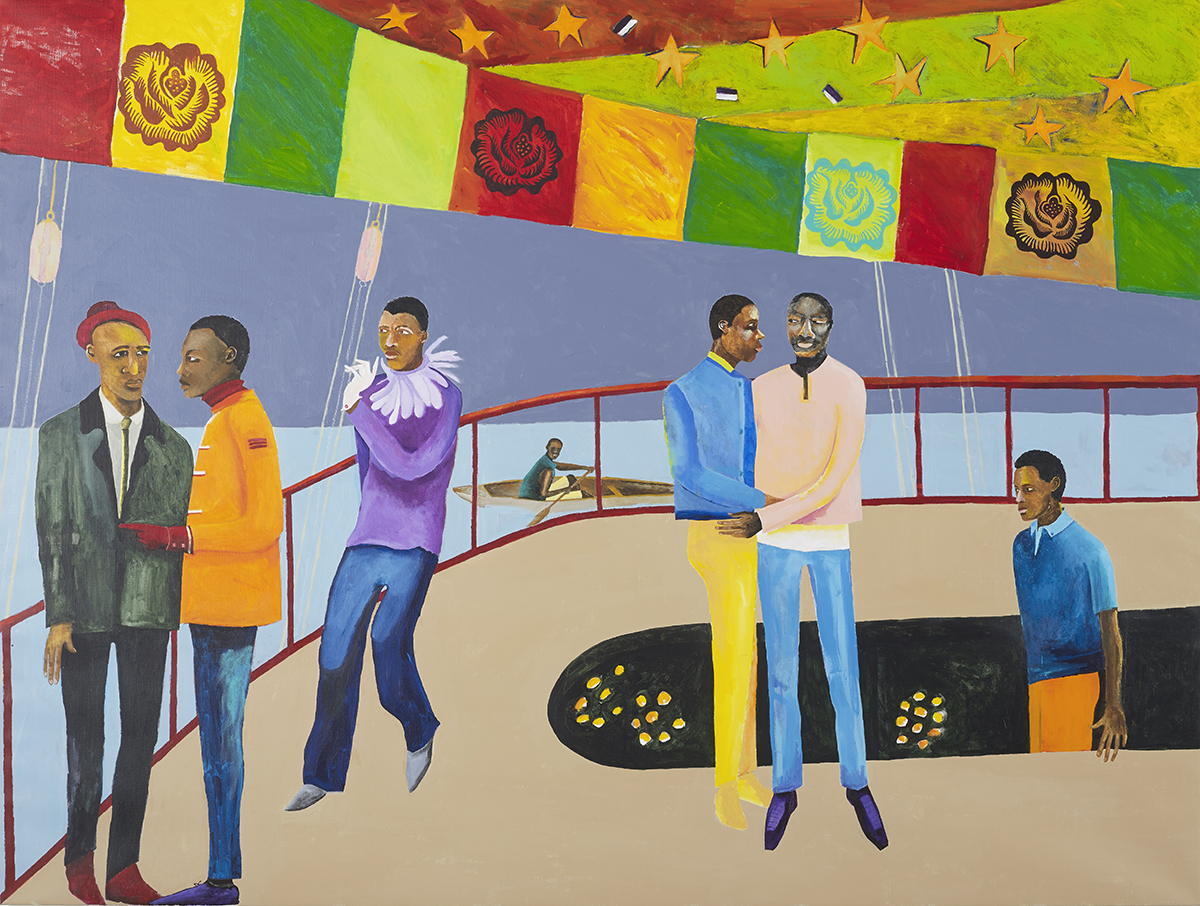

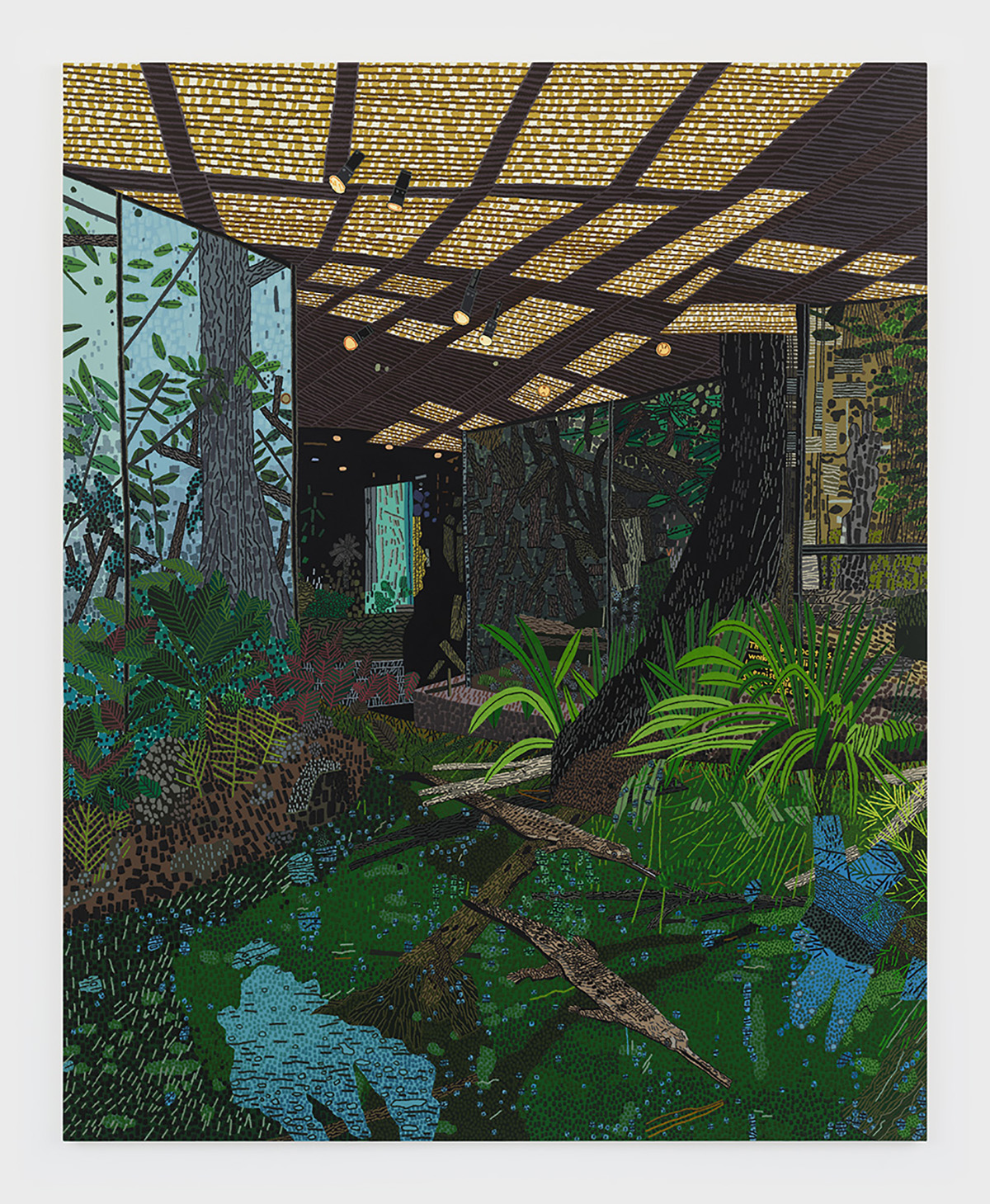

Mickalene Thomas, artist

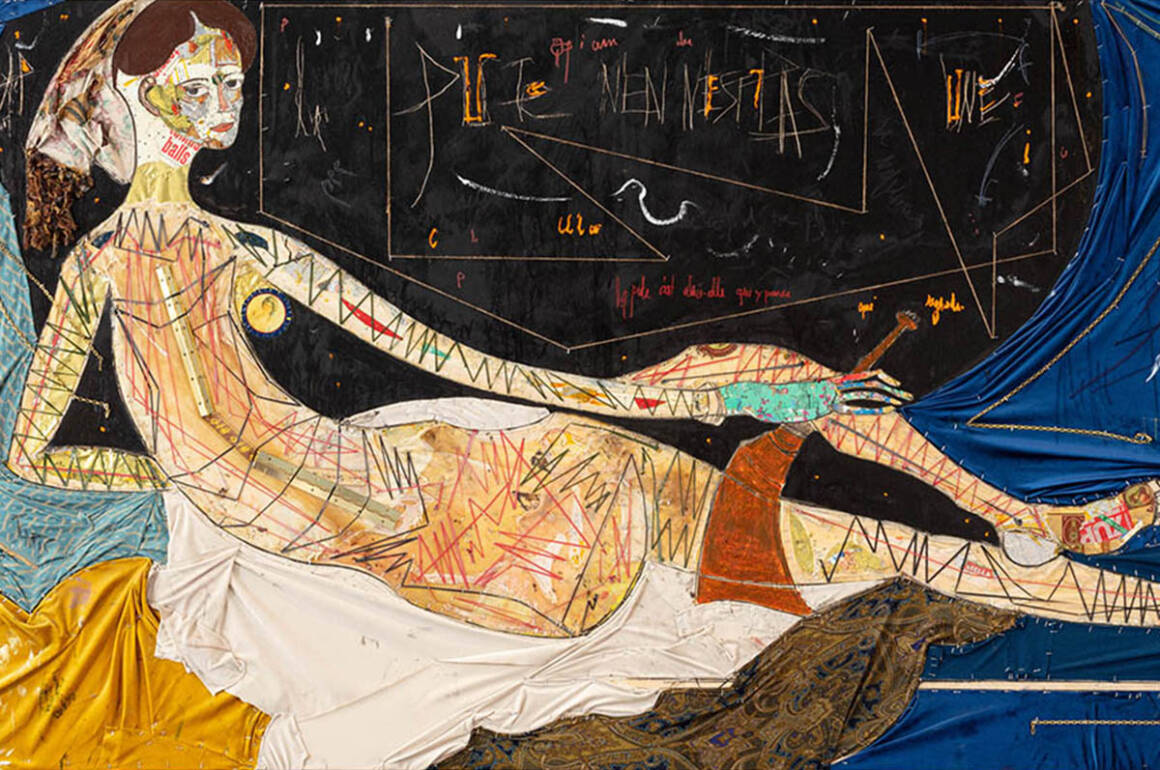

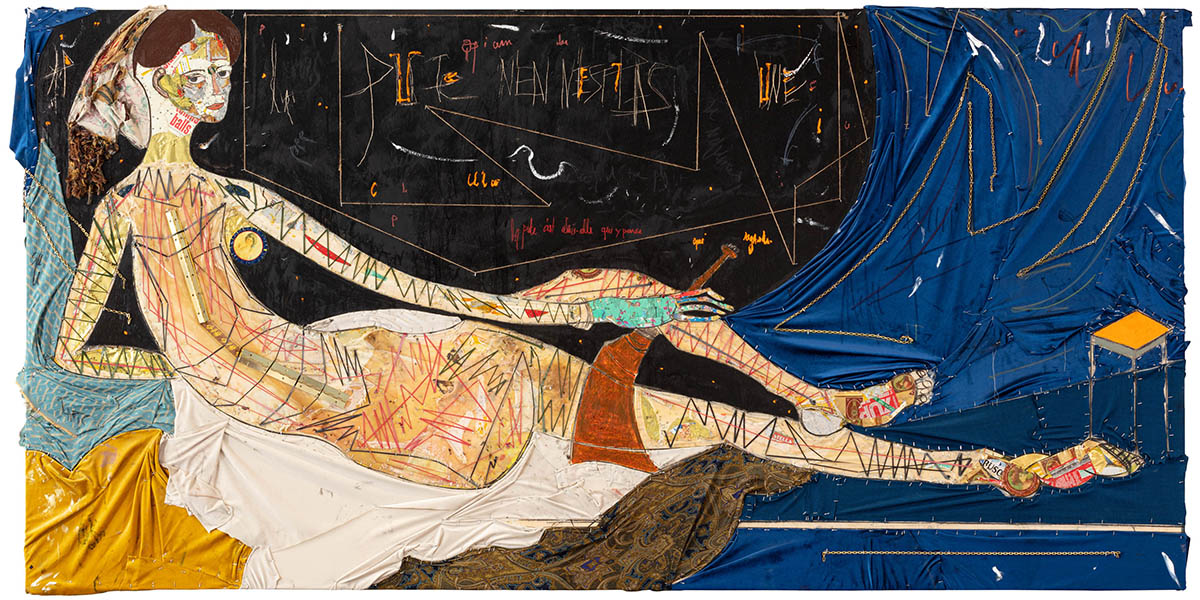

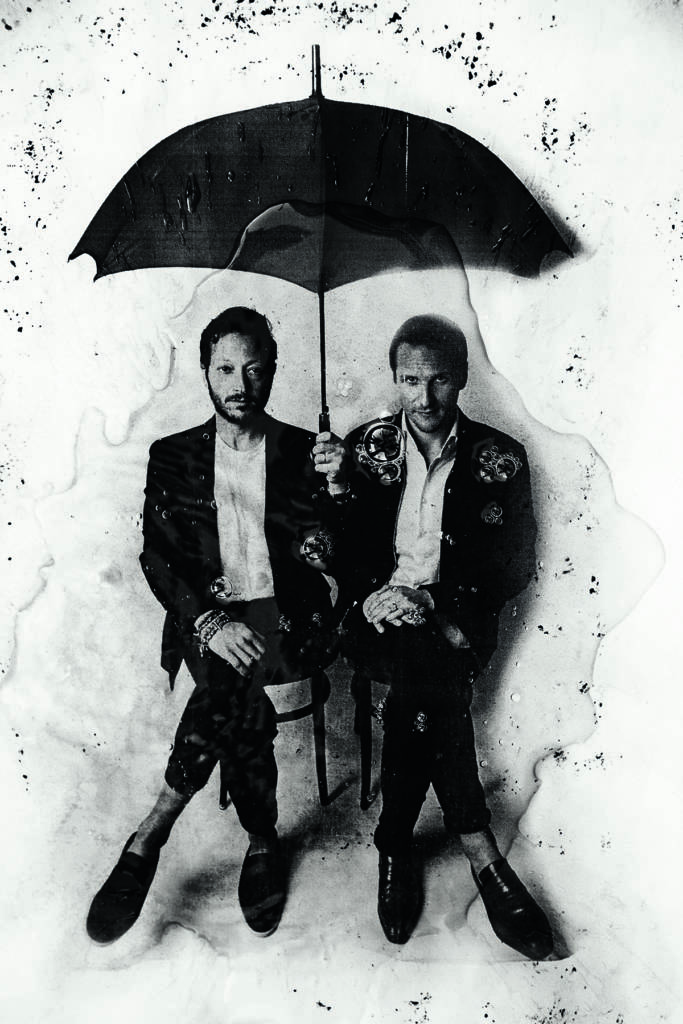

Mickalene Thomas, artist Steve Lazarides, artist

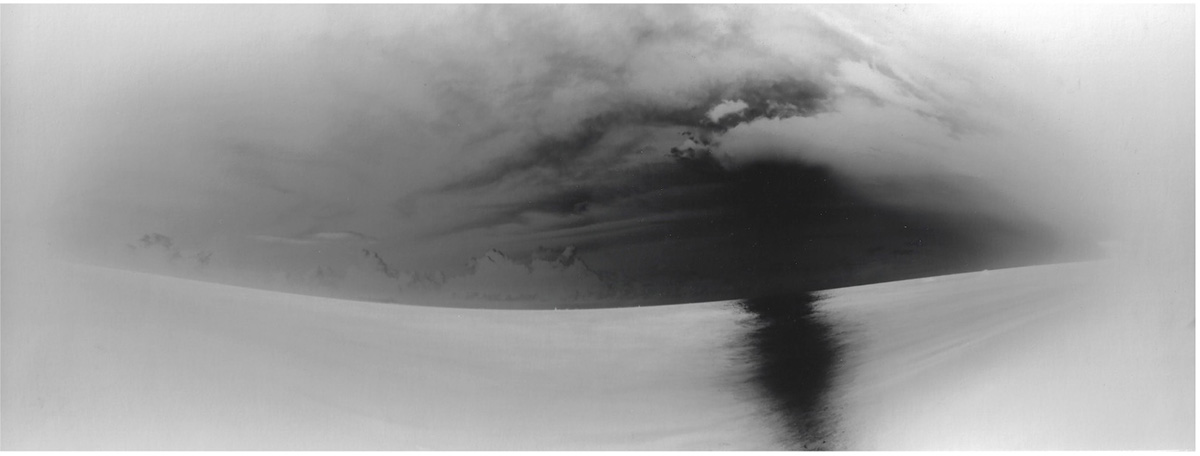

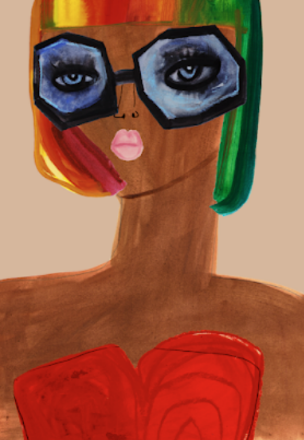

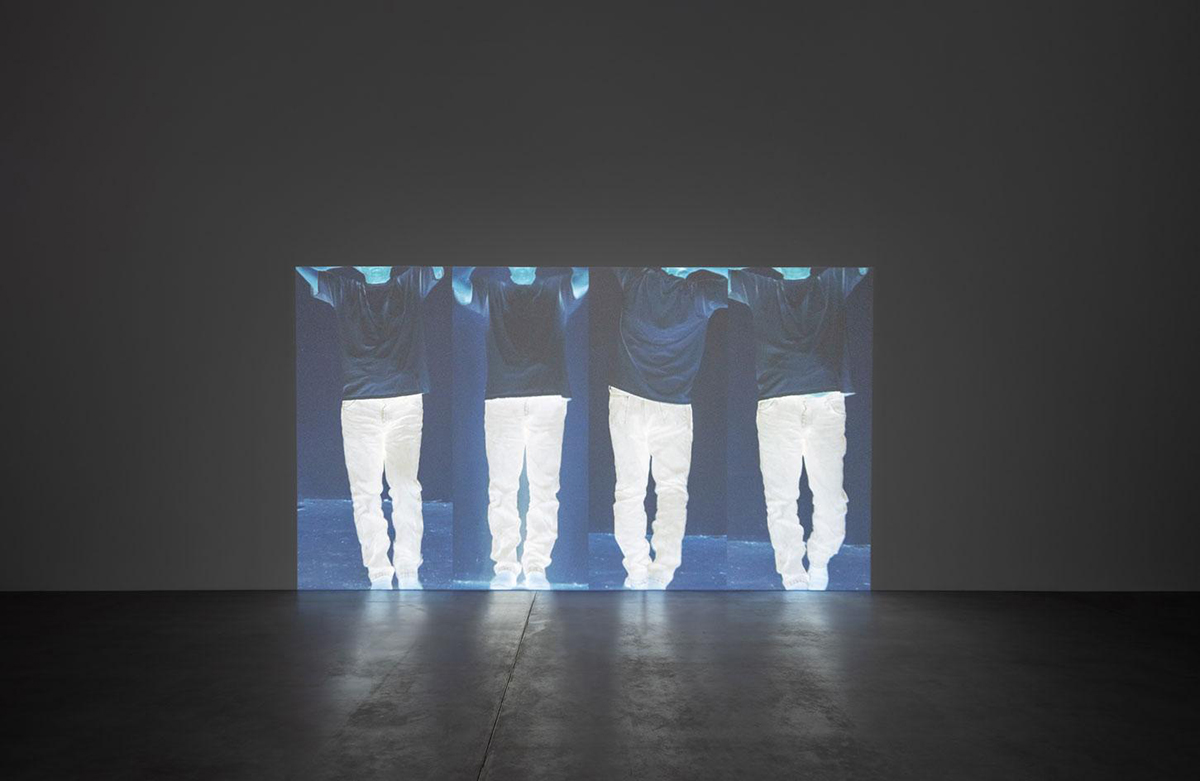

Steve Lazarides, artist

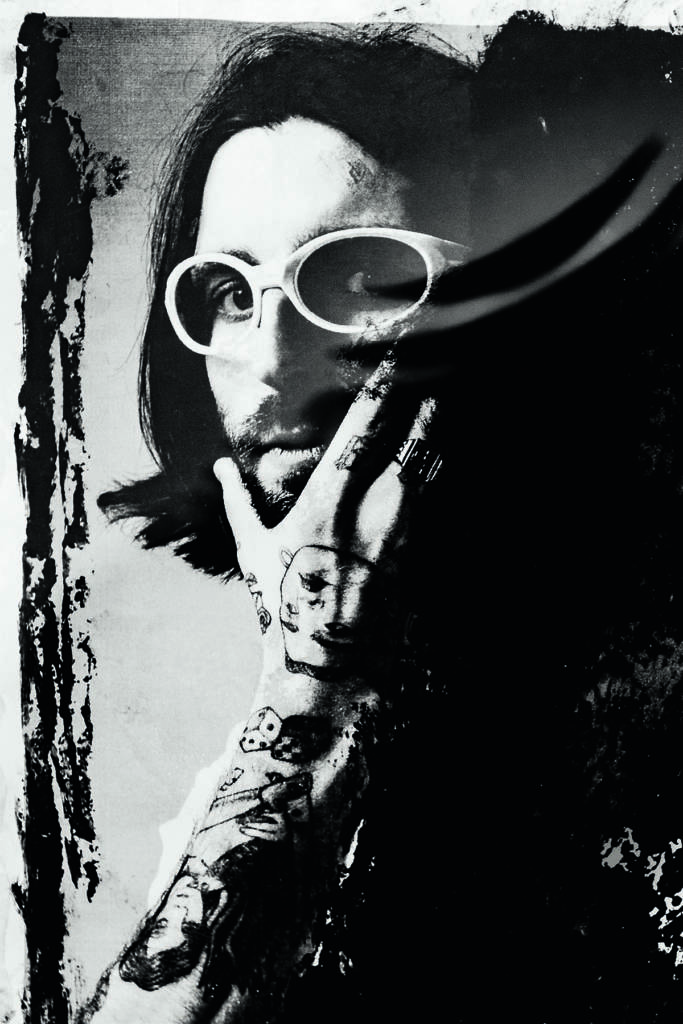

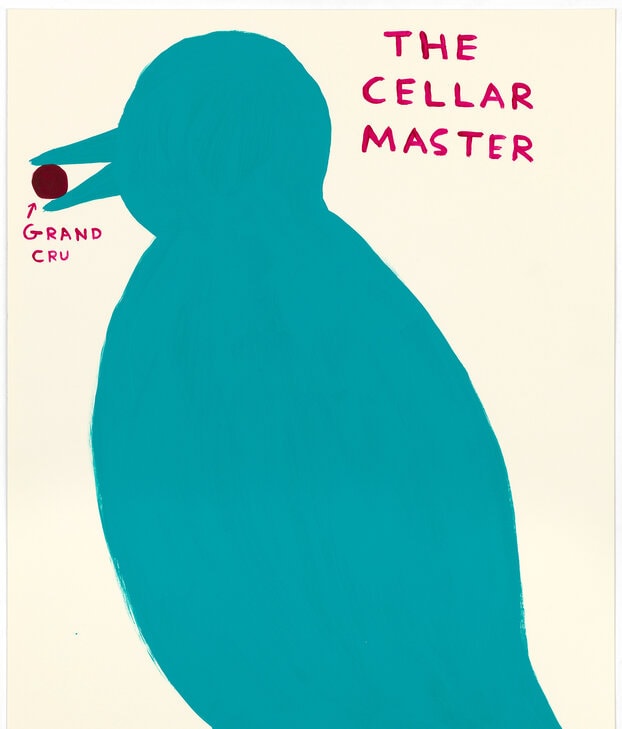

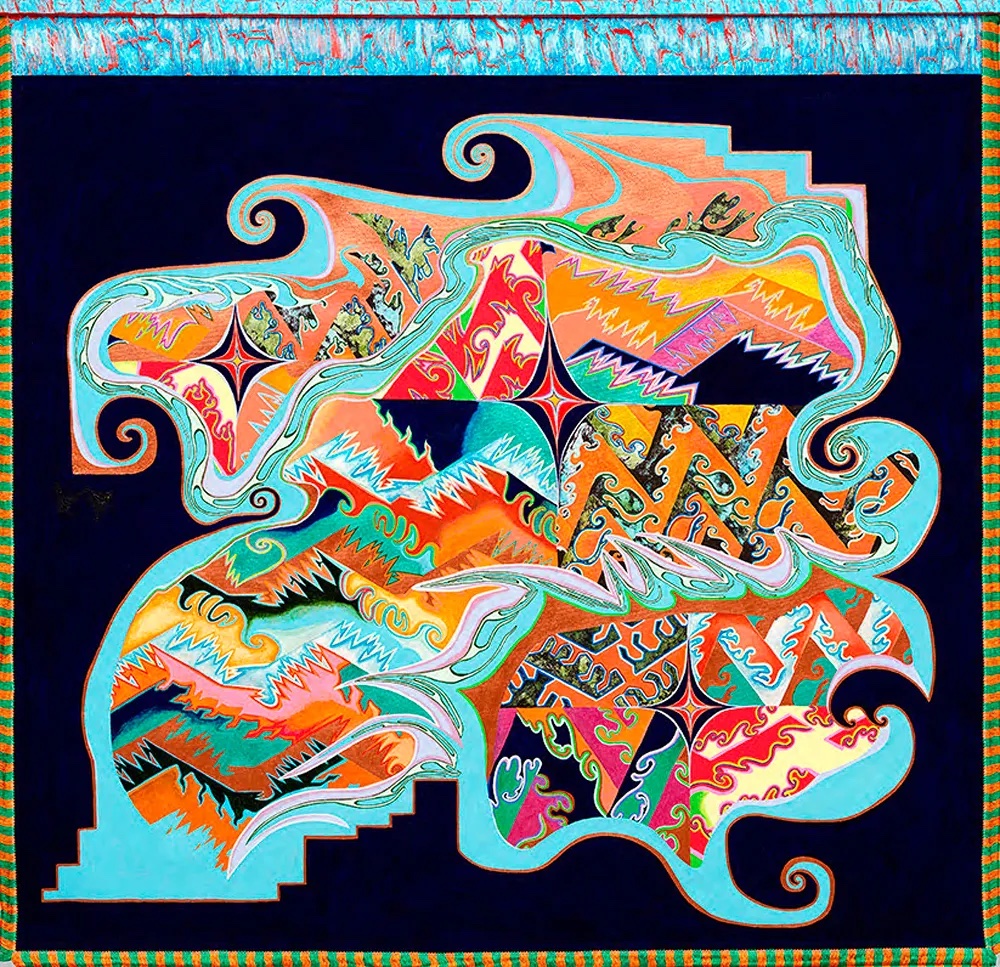

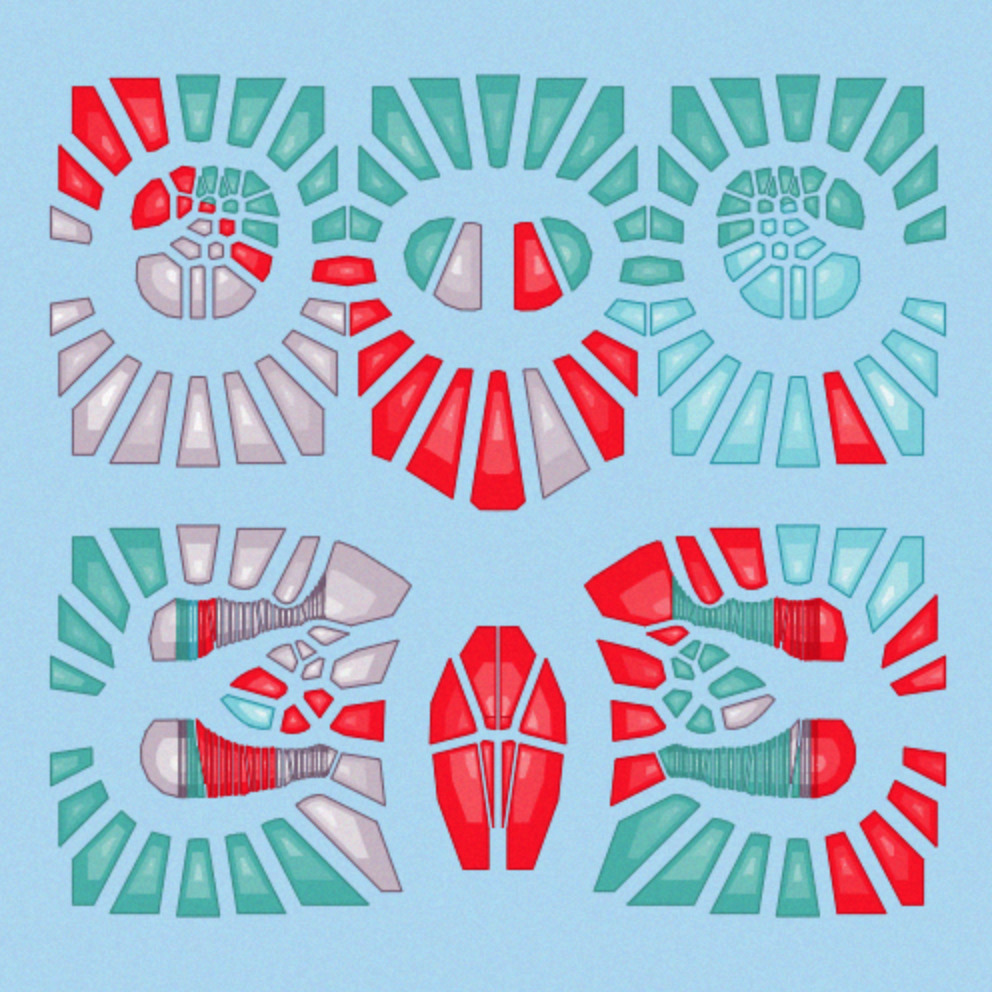

Philip Colbert, artist

Philip Colbert, artist

Alia Al-Senussi, cultural strategist and advisor in

Alia Al-Senussi, cultural strategist and advisor in

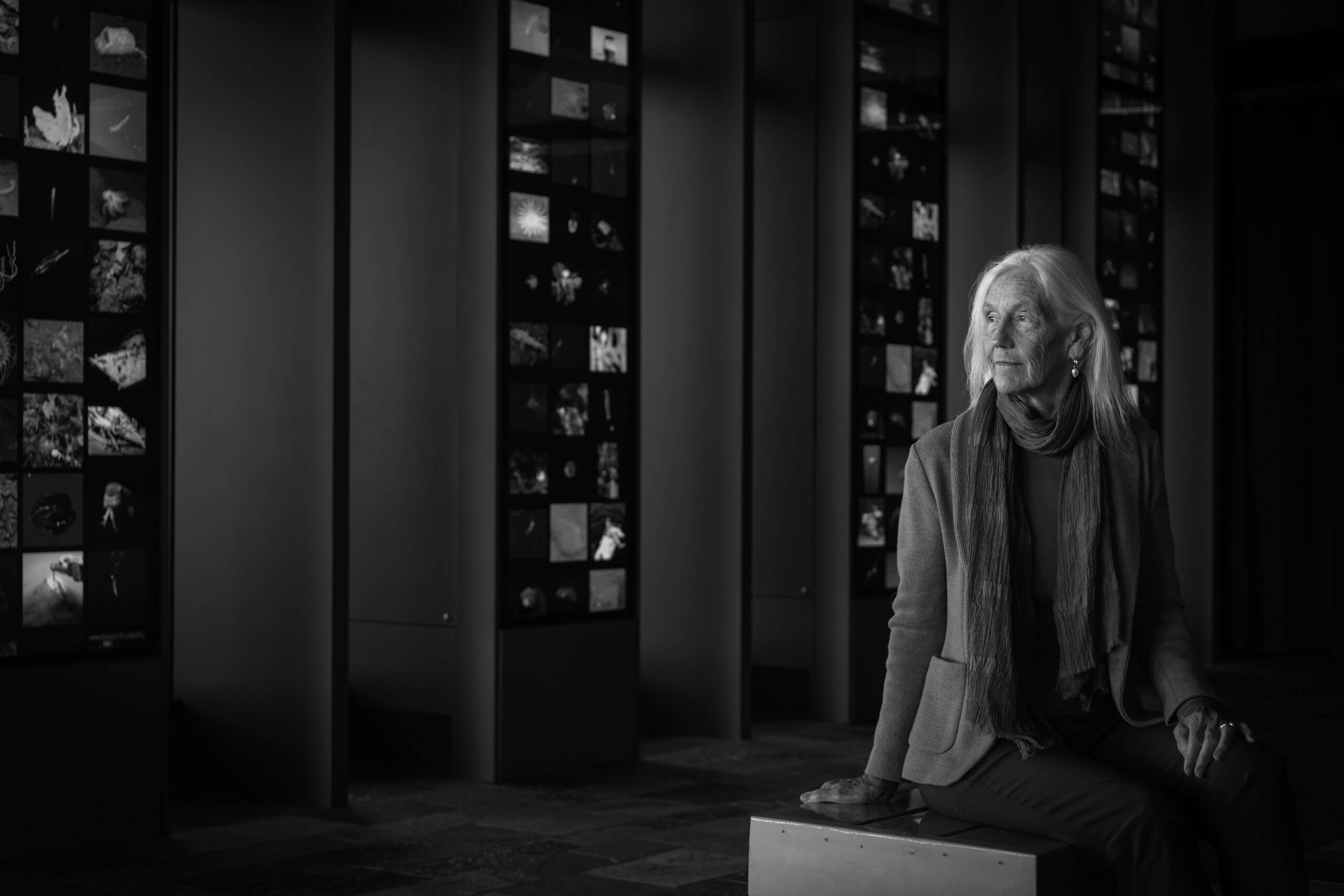

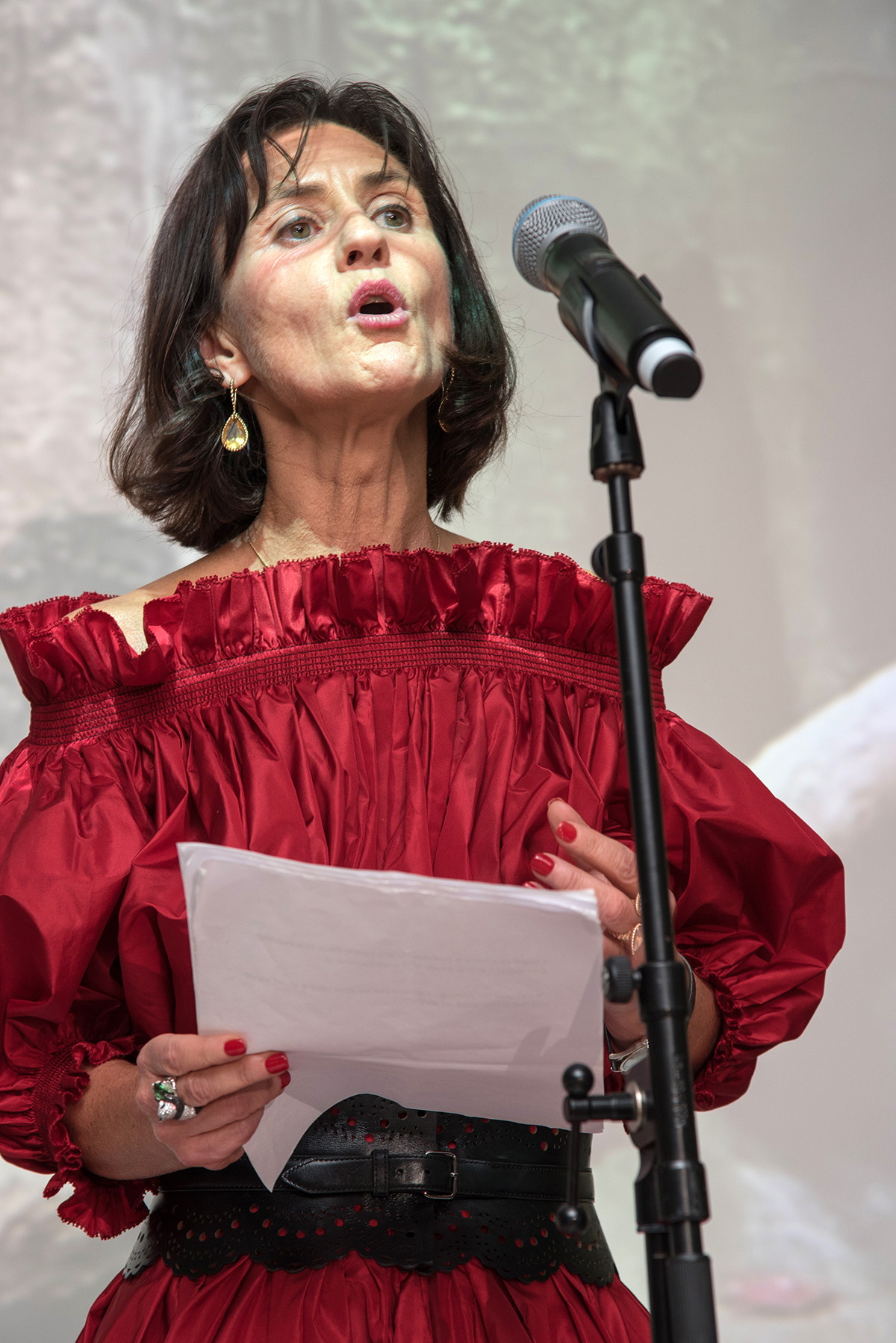

Maria Sukkar, collector and member of the International Council at Tate

Maria Sukkar, collector and member of the International Council at Tate

Sophie Neuendorf, vice president, Artnet

Sophie Neuendorf, vice president, Artnet

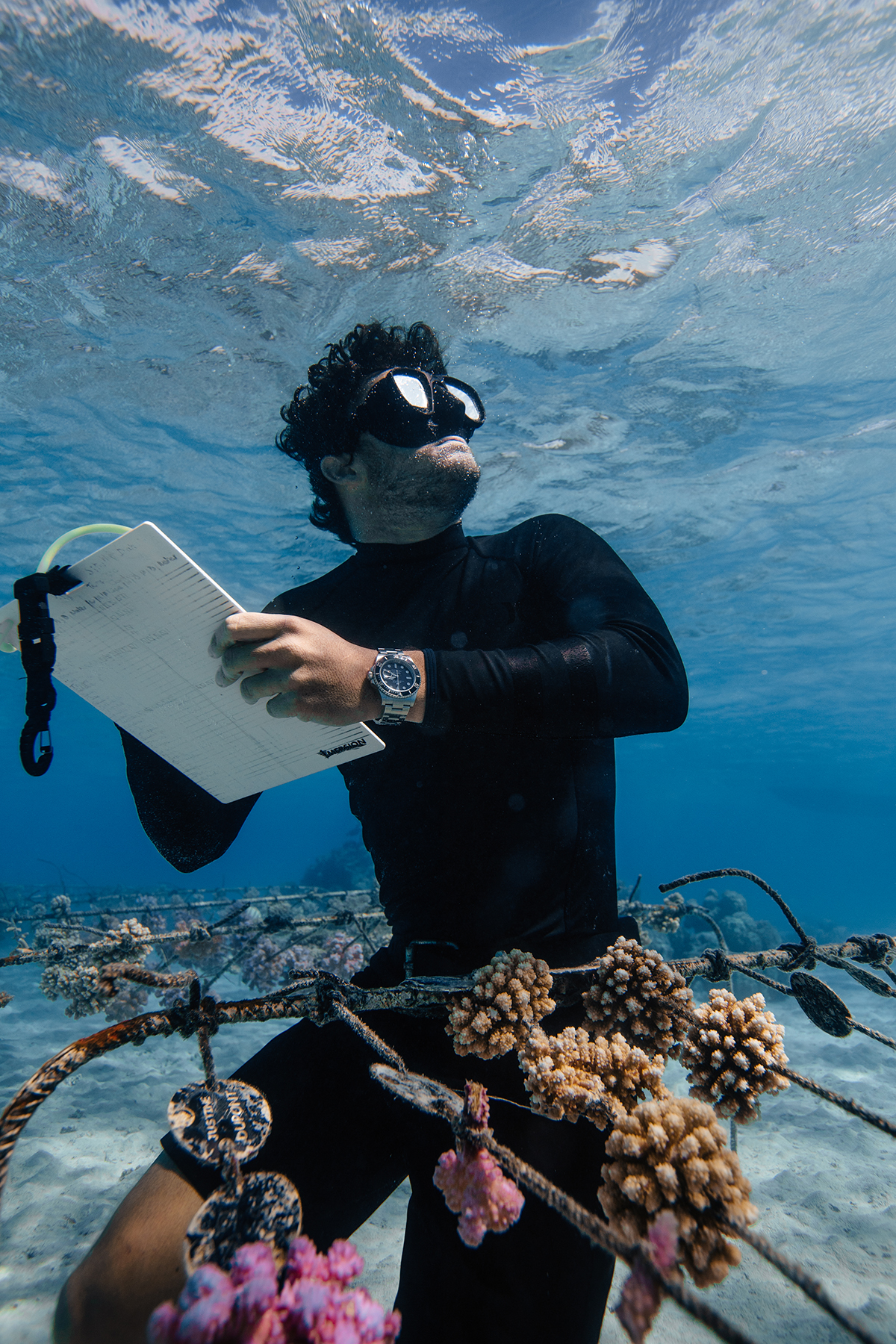

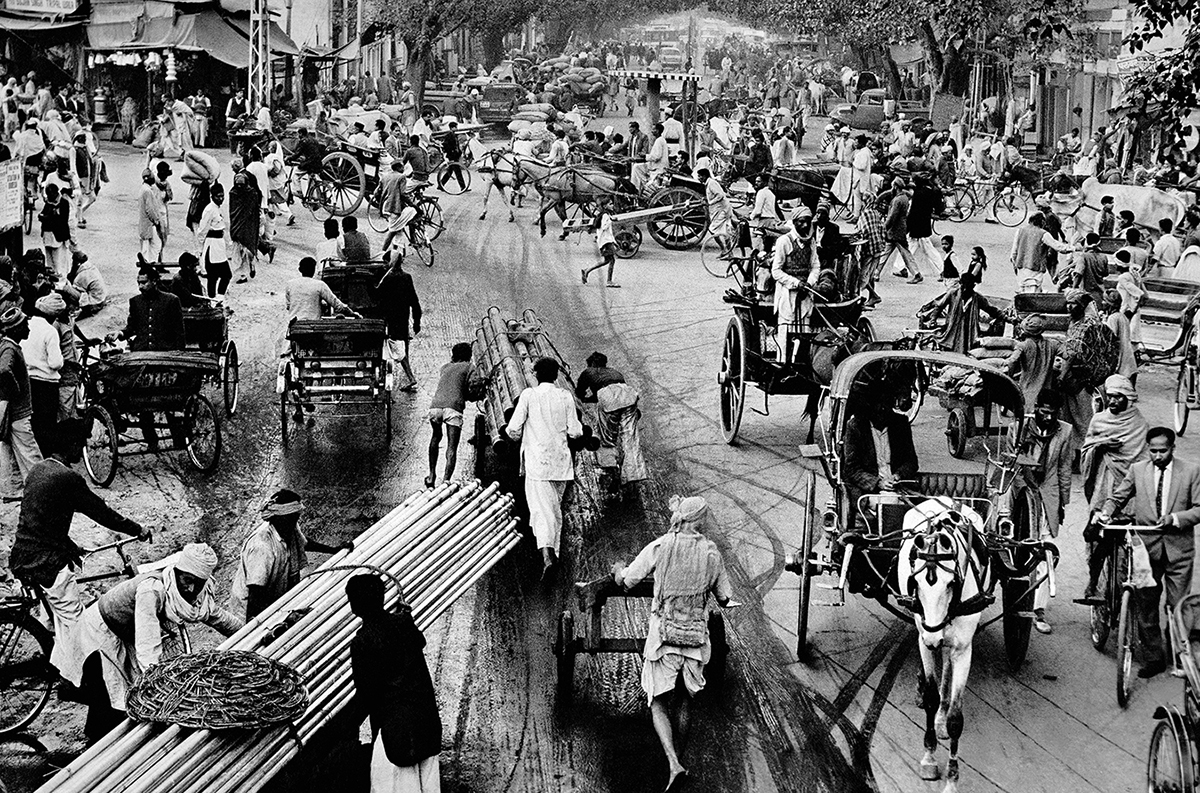

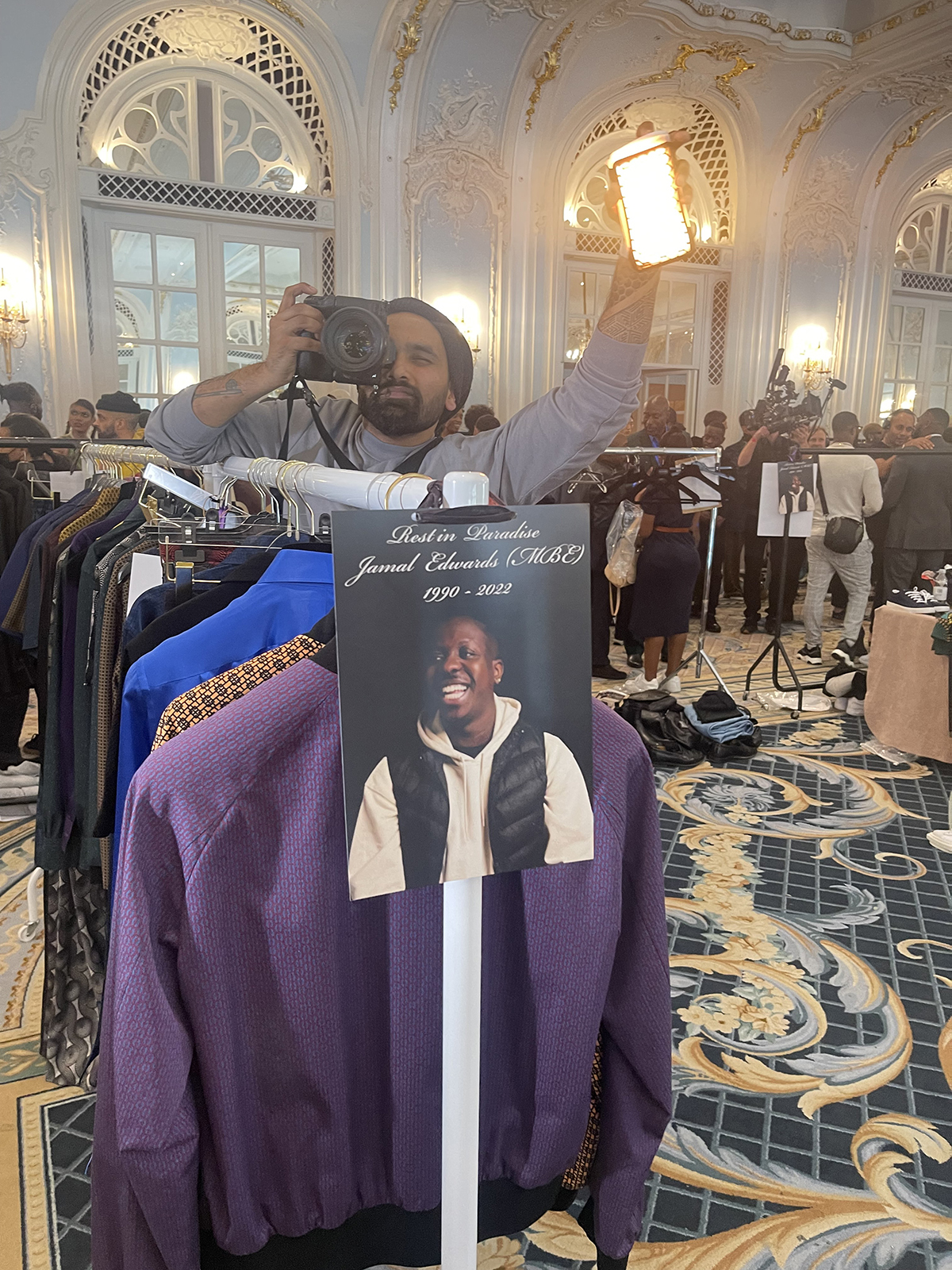

Azu Nwagbogu, founder, African Artists’ Foundation and director, LagosPhoto Festival

Azu Nwagbogu, founder, African Artists’ Foundation and director, LagosPhoto Festival

Darius Sanai,

Darius Sanai,

Vanessa Guo, co-founder and partner, Galerie Marguo

Vanessa Guo, co-founder and partner, Galerie Marguo

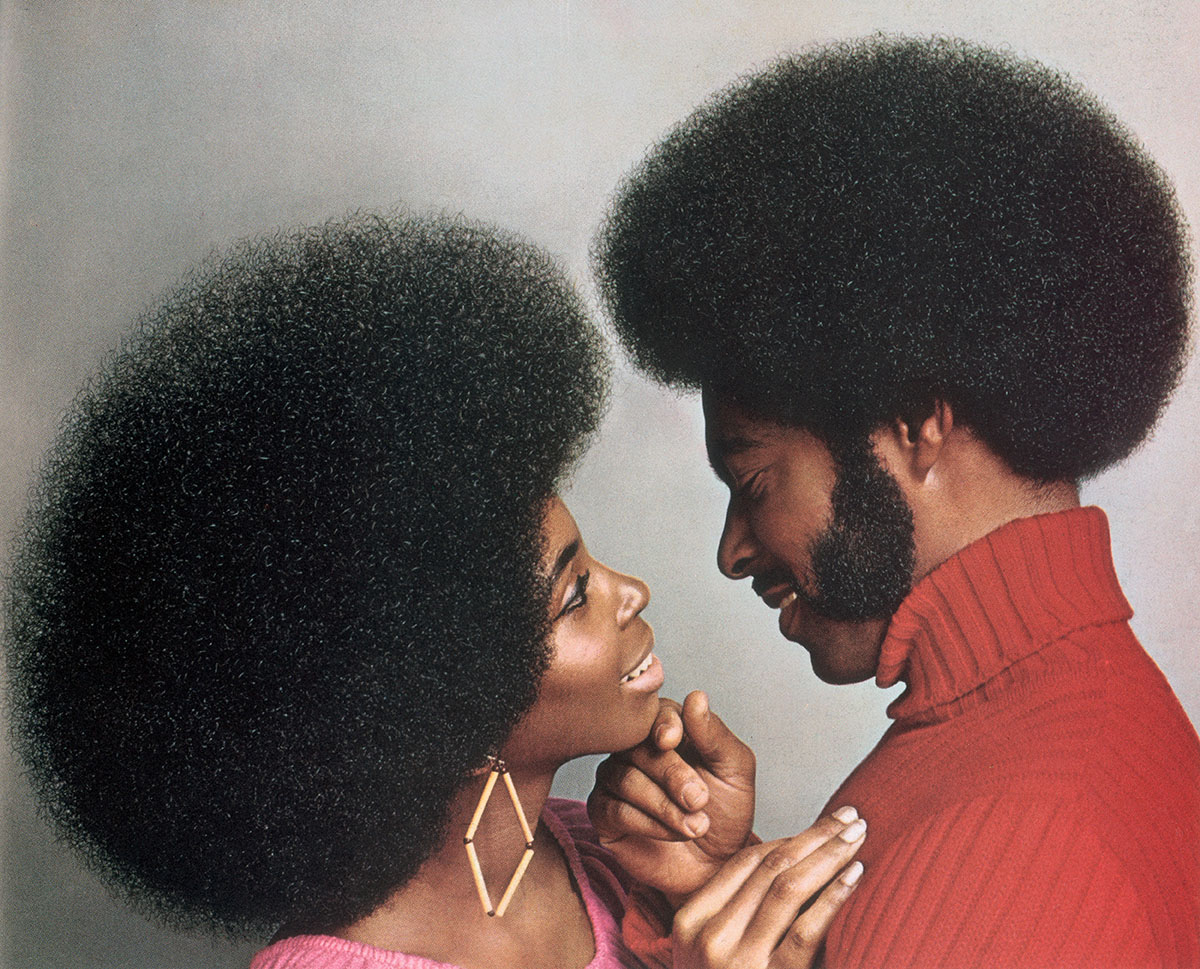

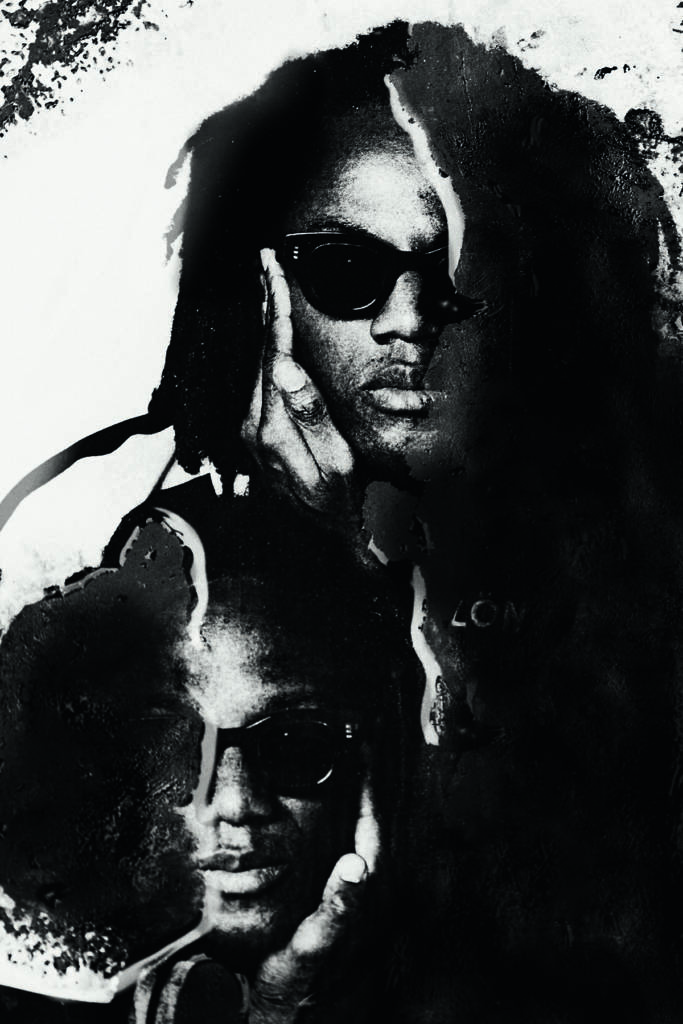

Racquel Chevremont, collector and curator

Racquel Chevremont, collector and curator

Lorin Gu, founder, Recharge Foundation

Lorin Gu, founder, Recharge Foundation

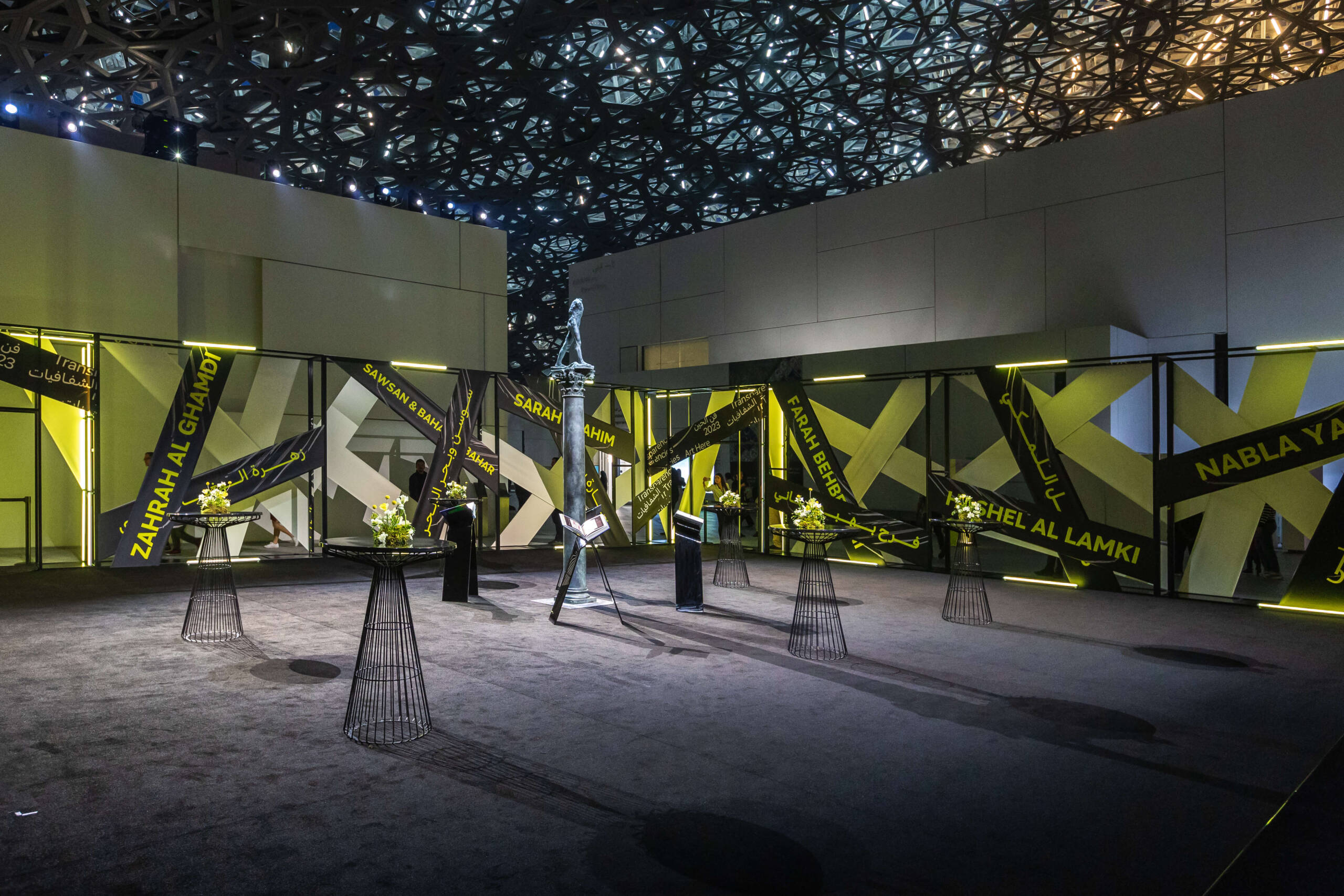

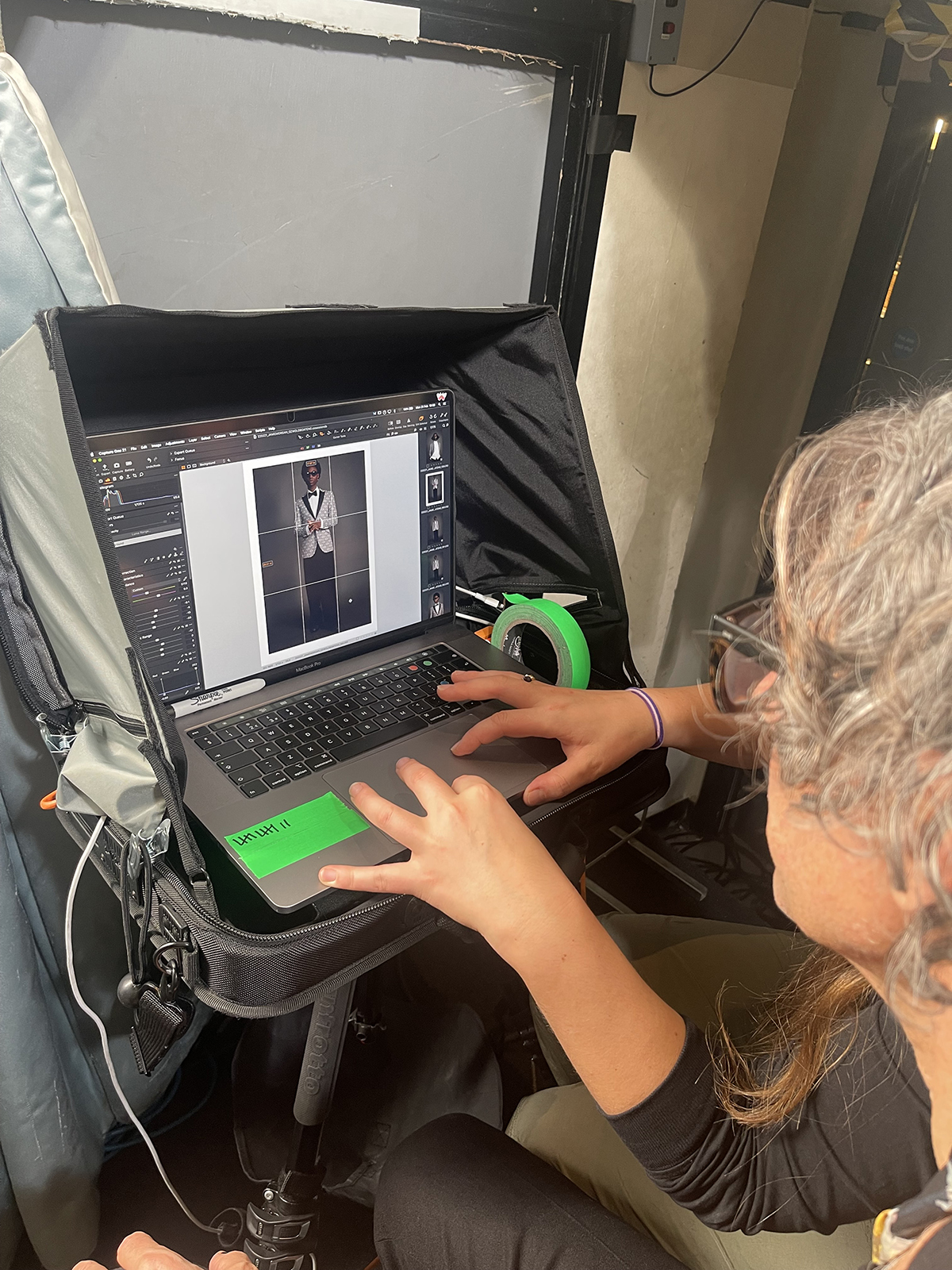

I have said to my team that I want 50/50

I have said to my team that I want 50/50

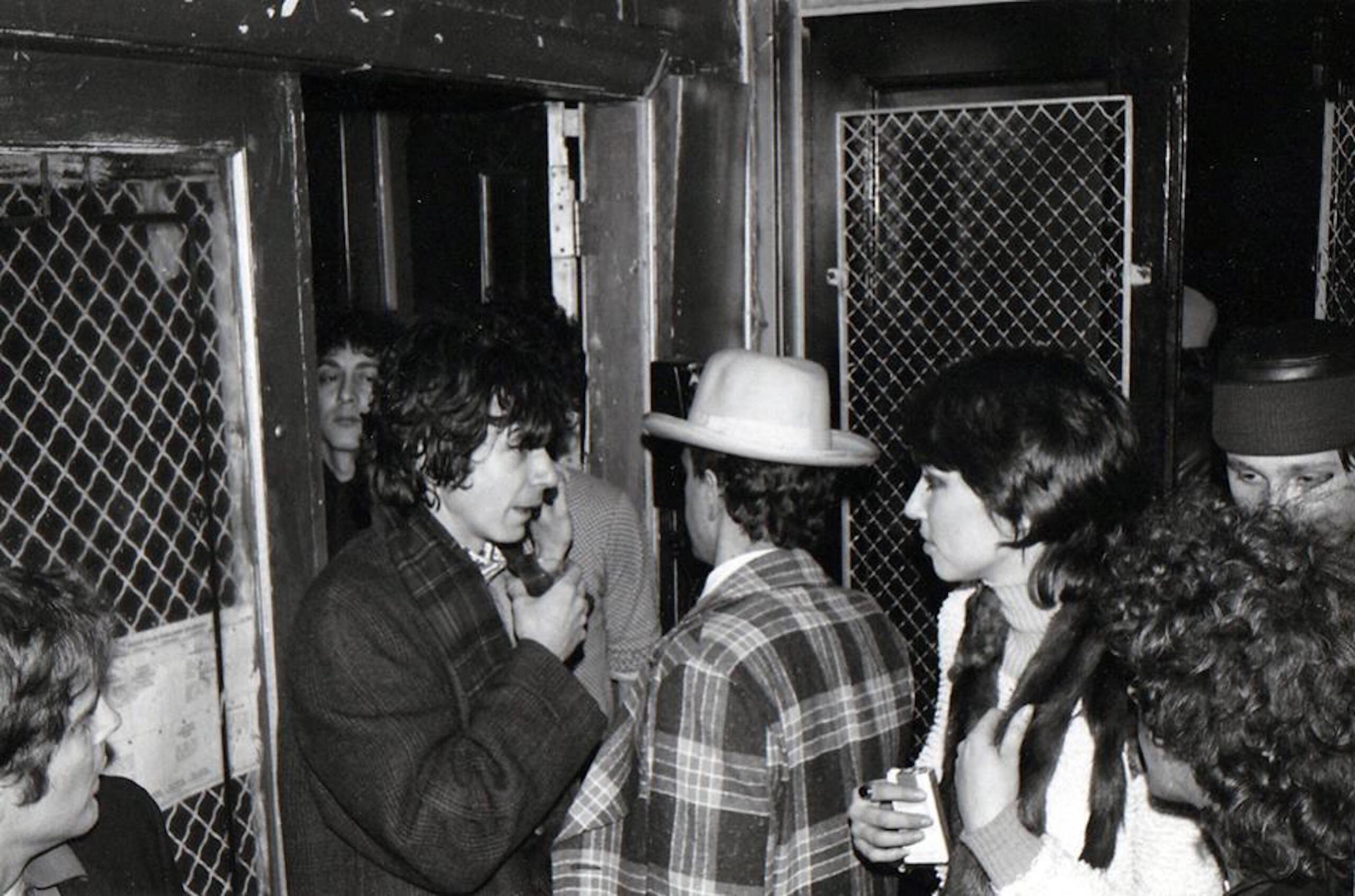

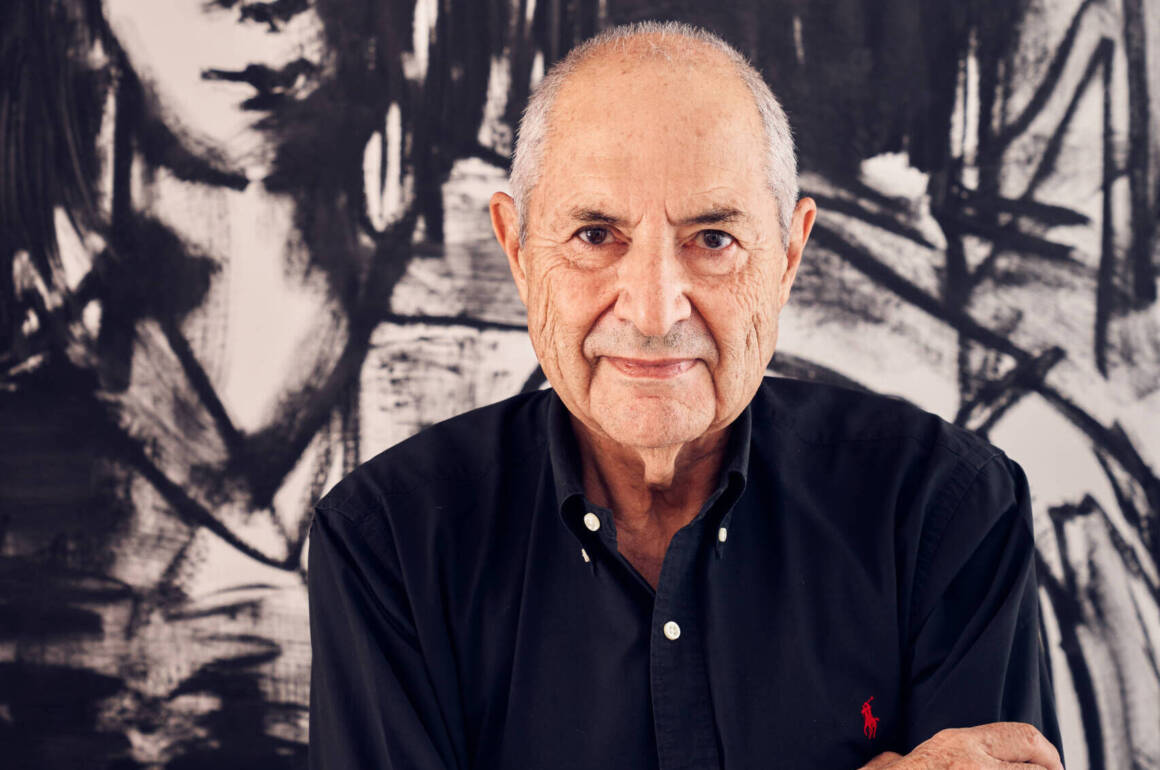

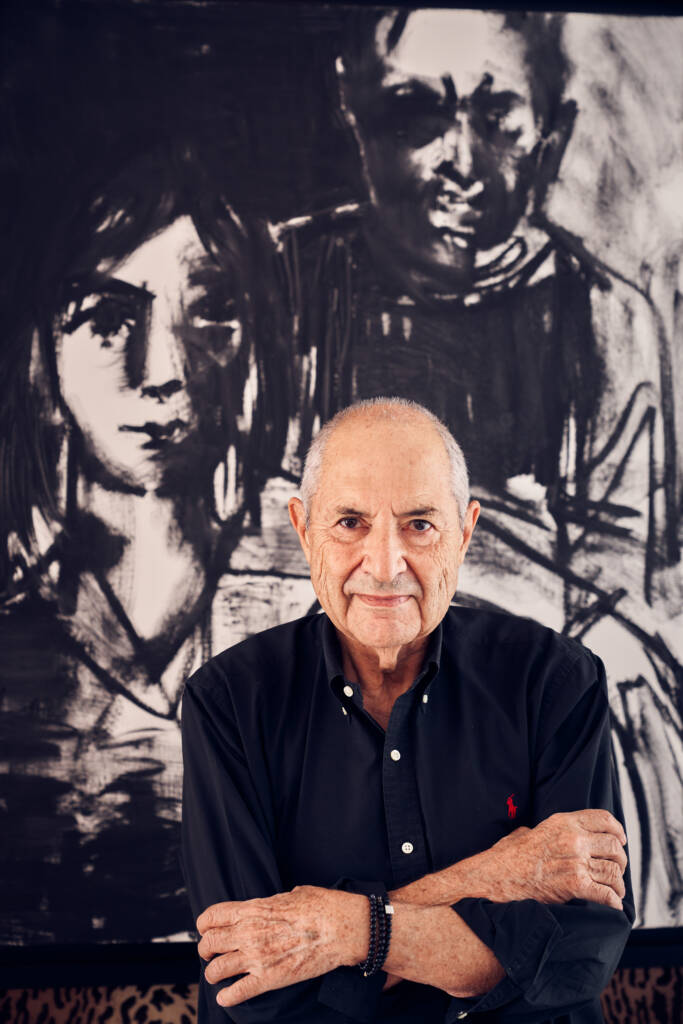

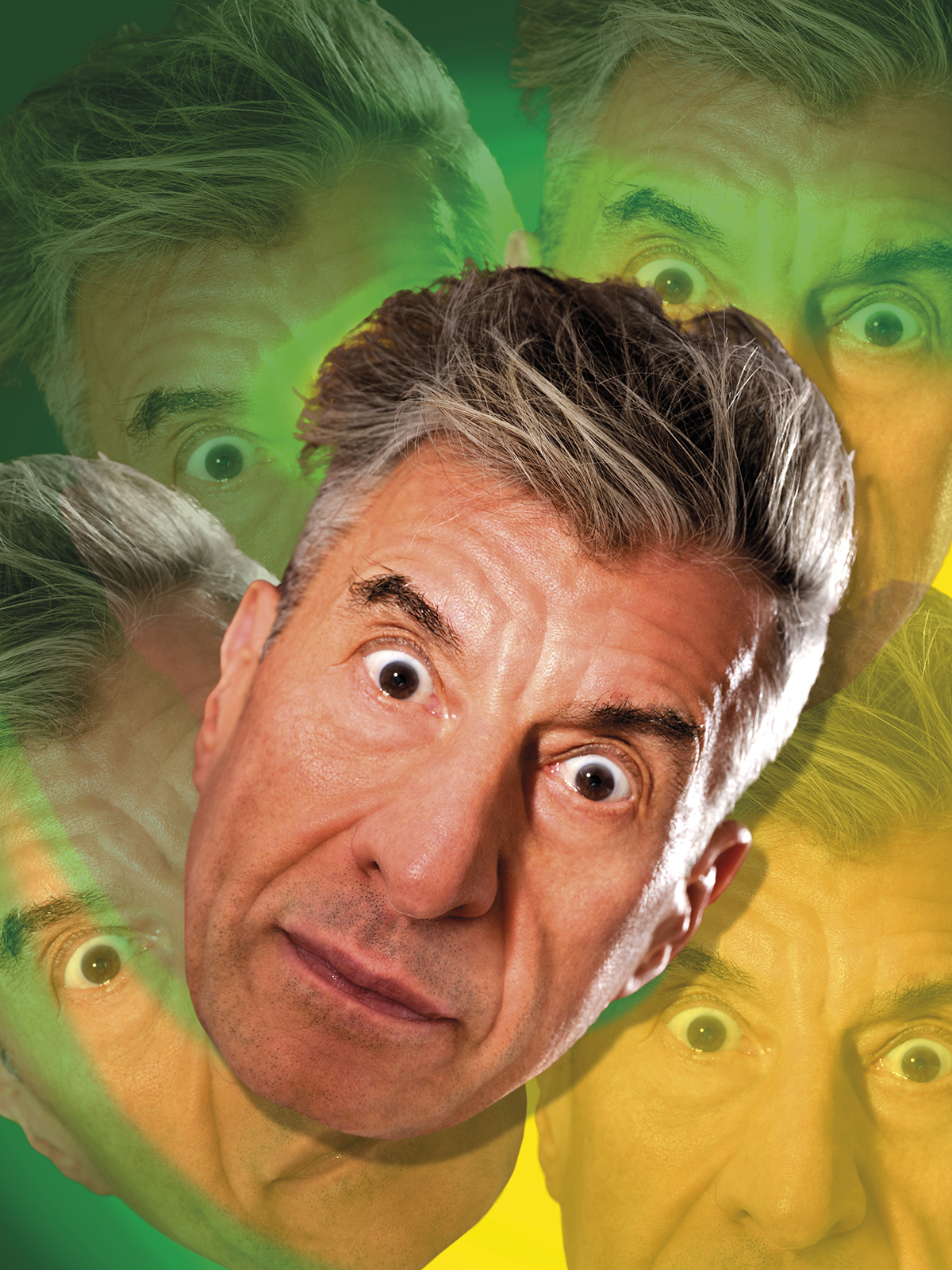

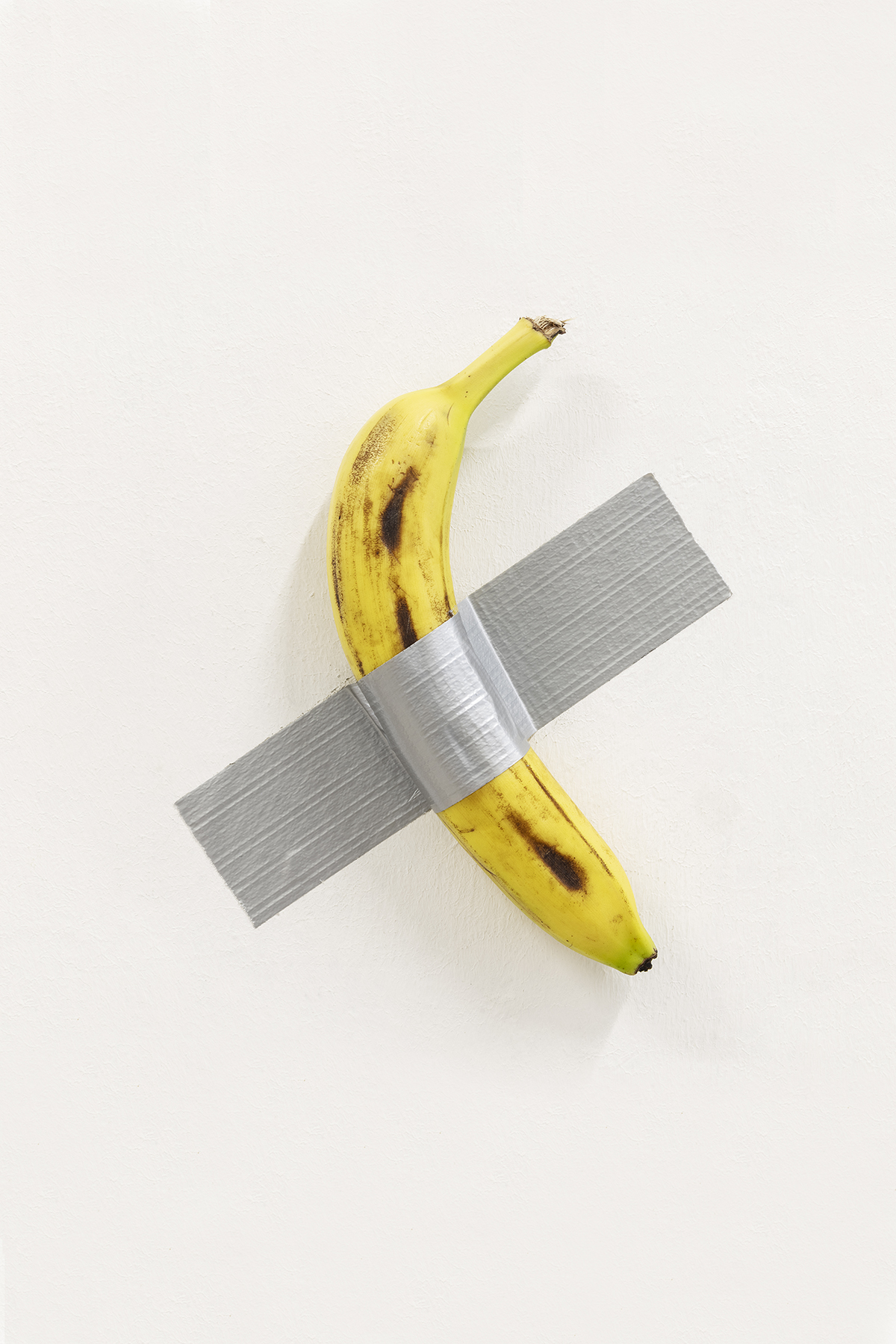

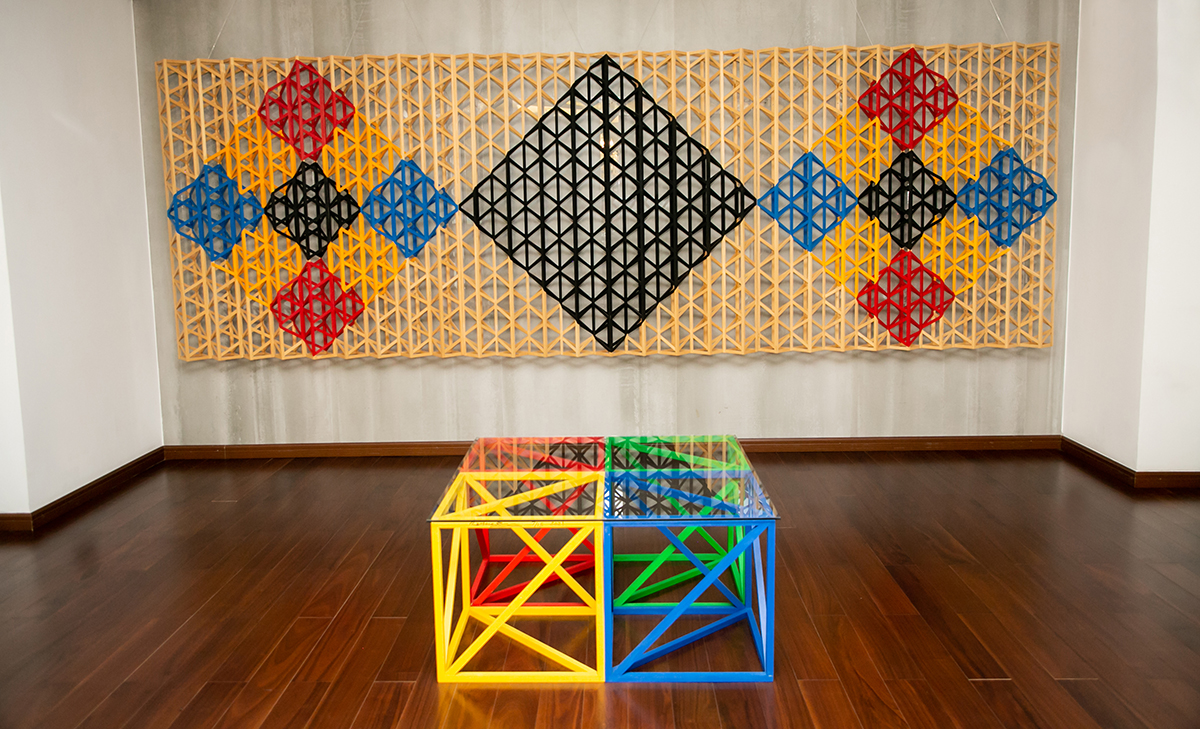

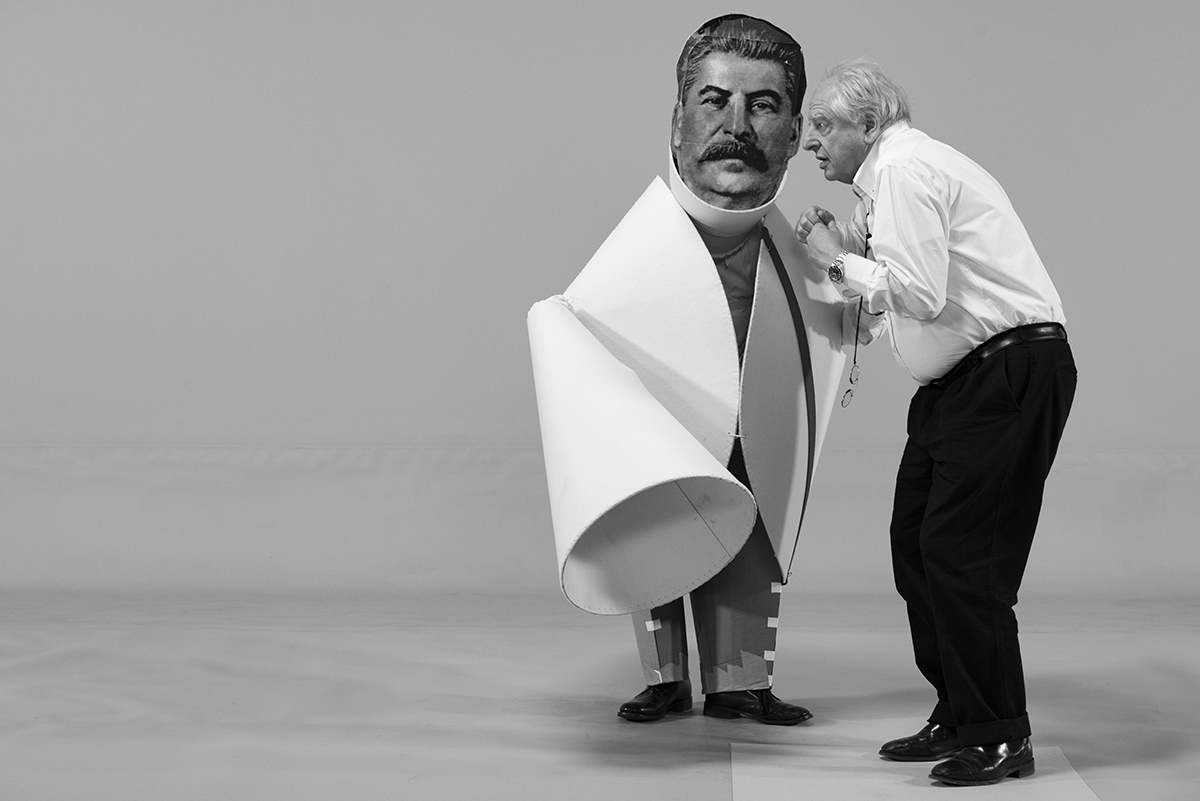

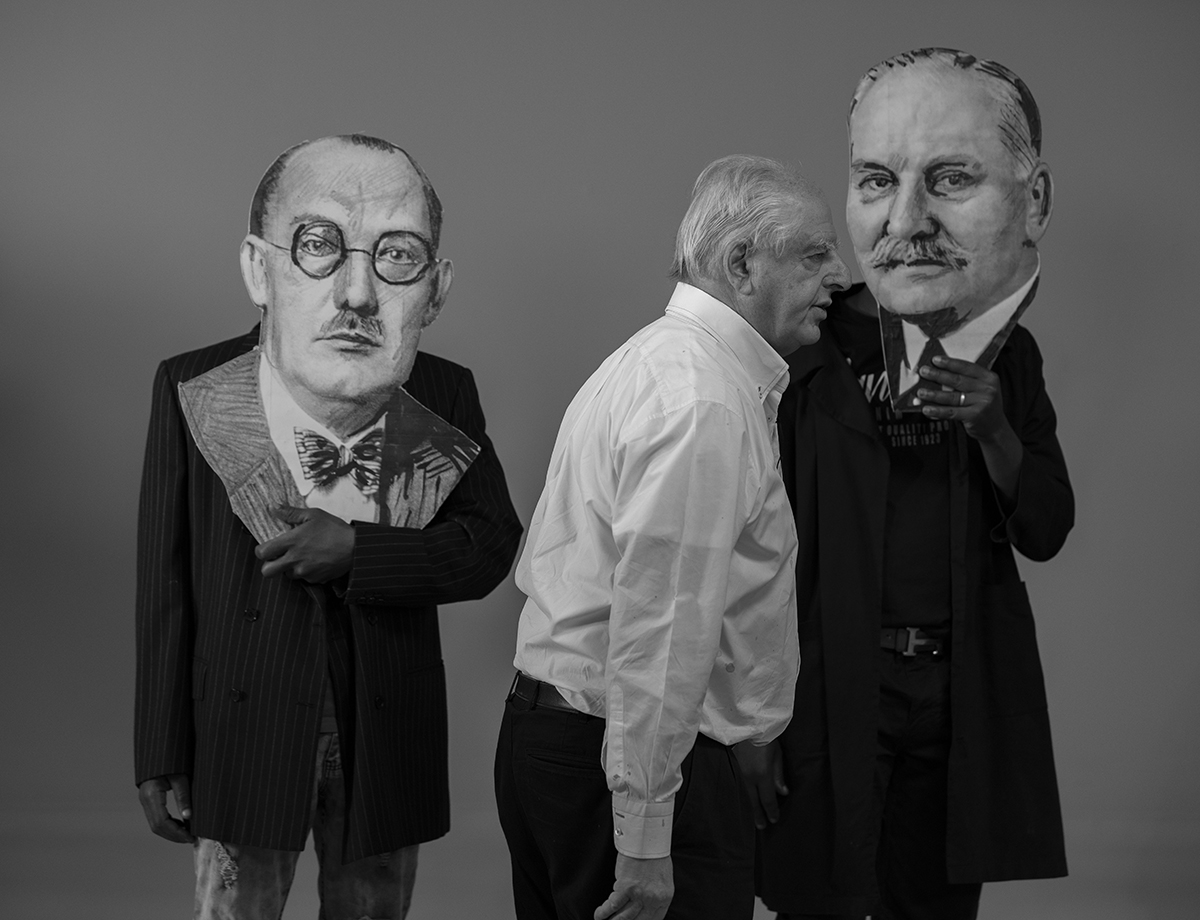

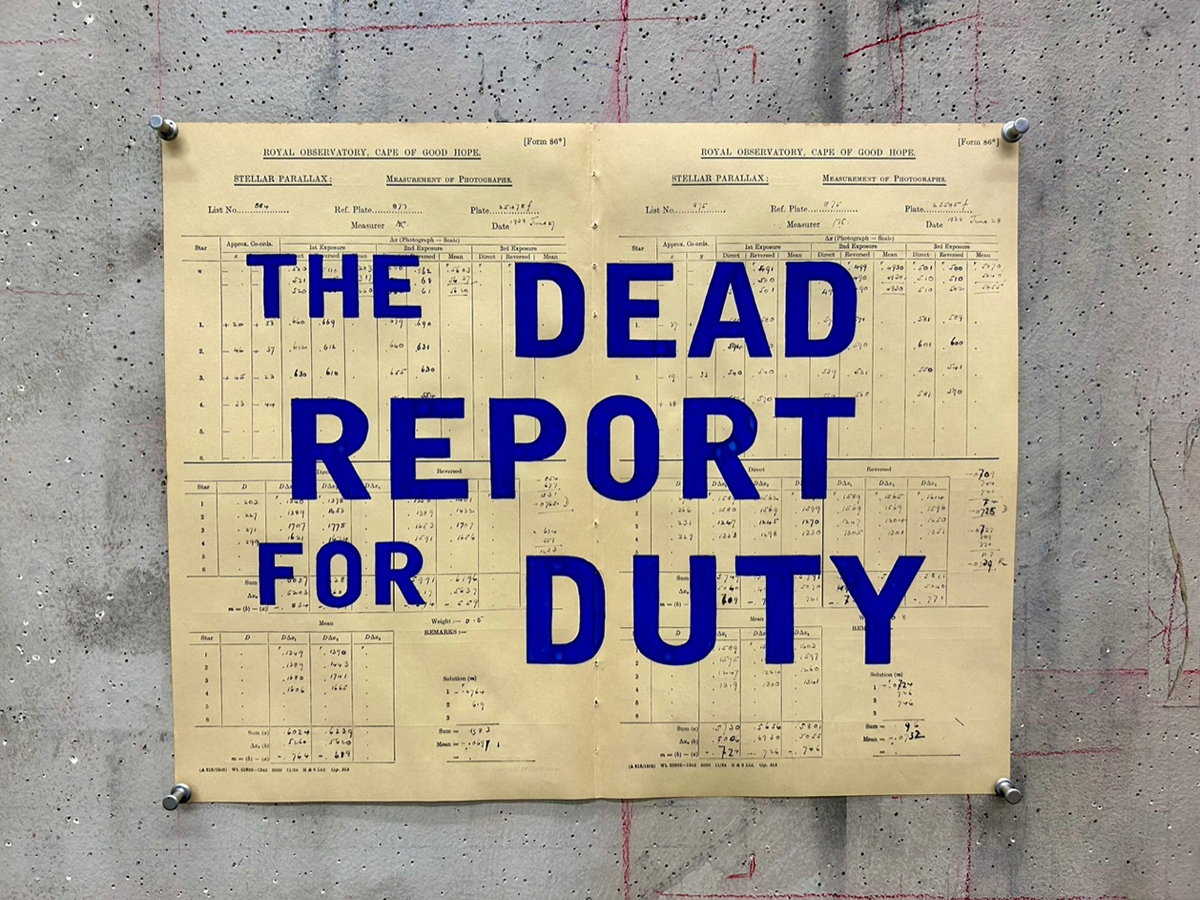

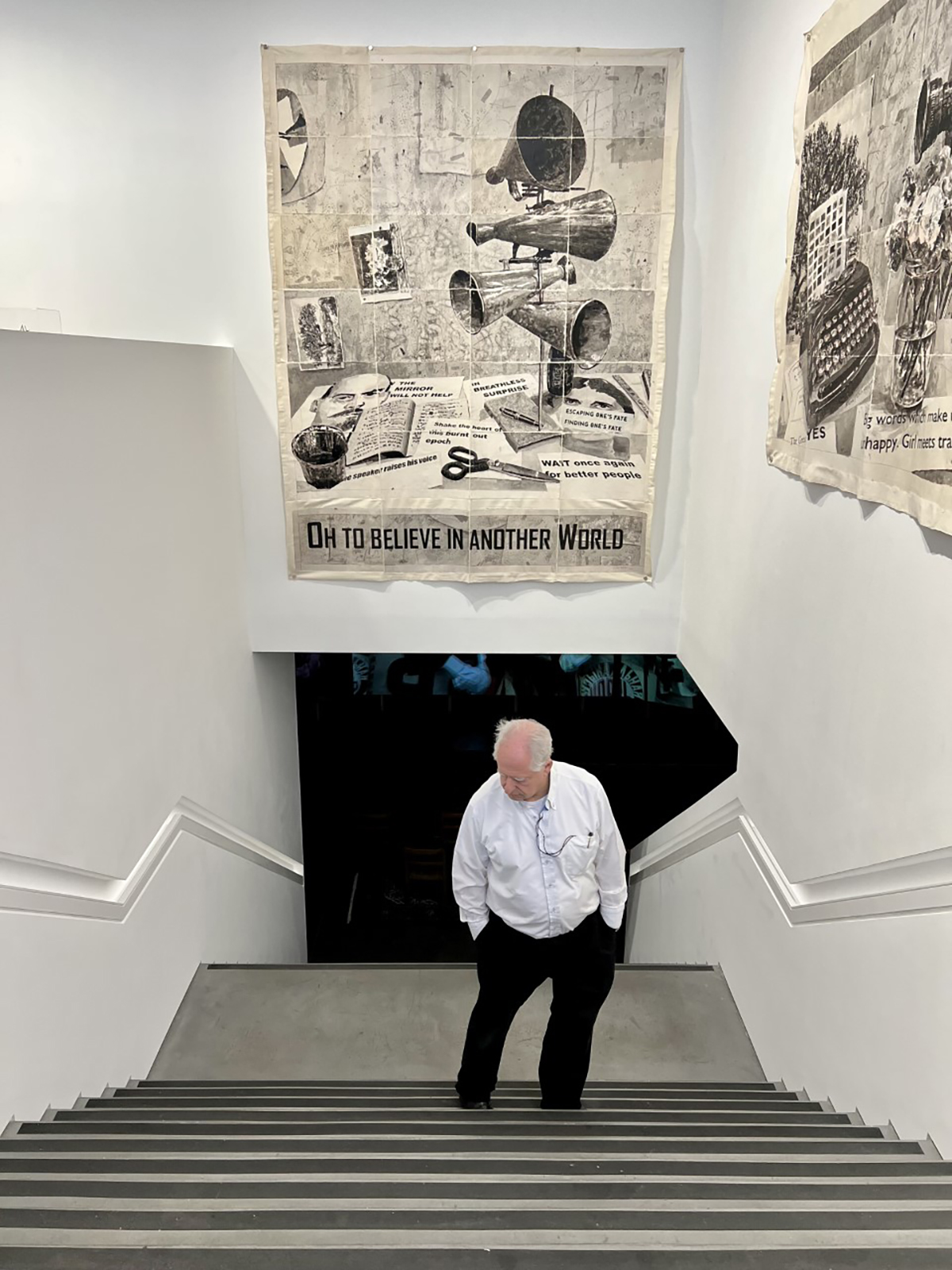

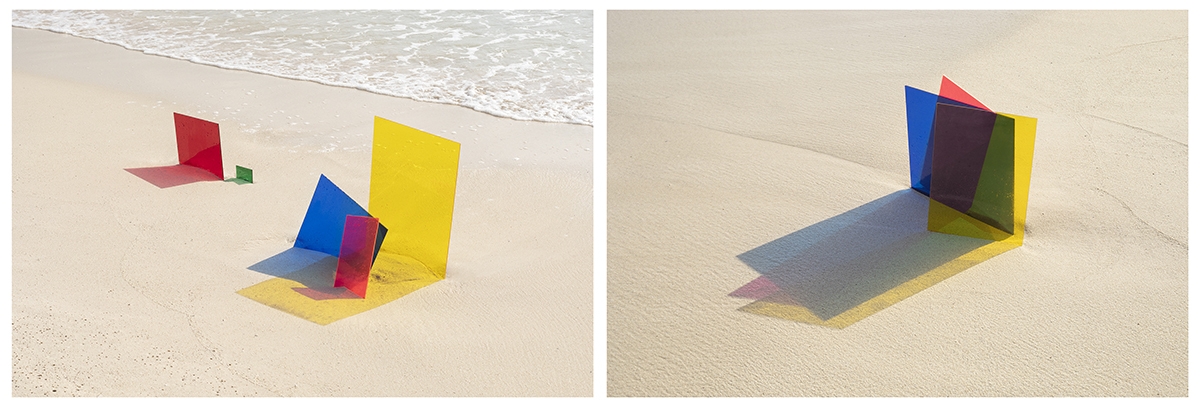

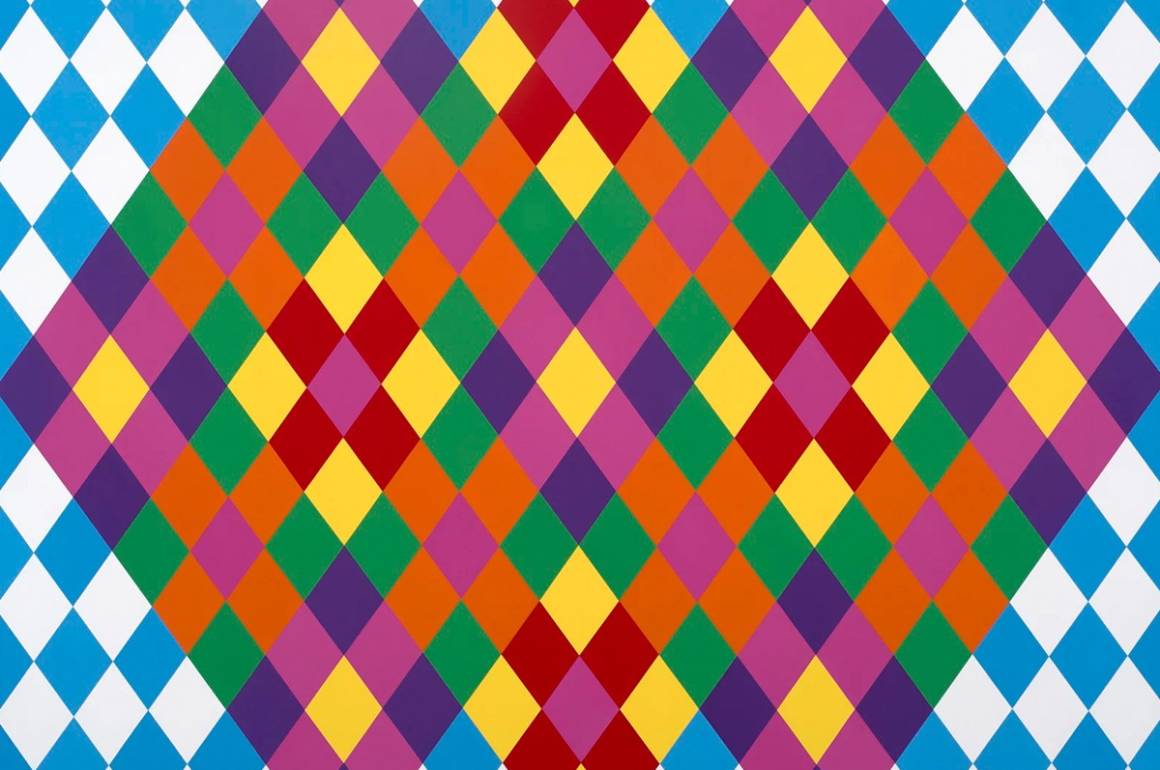

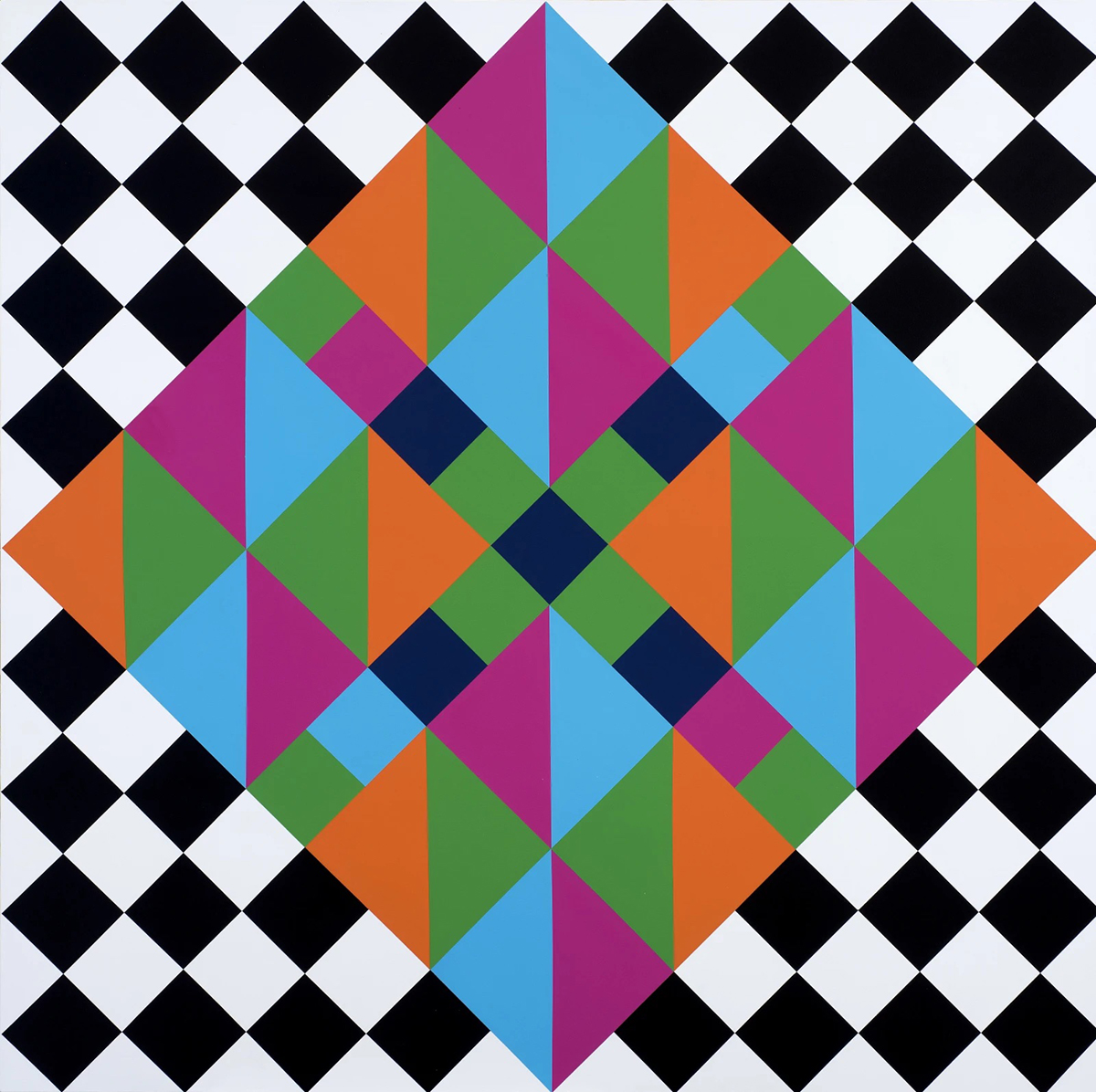

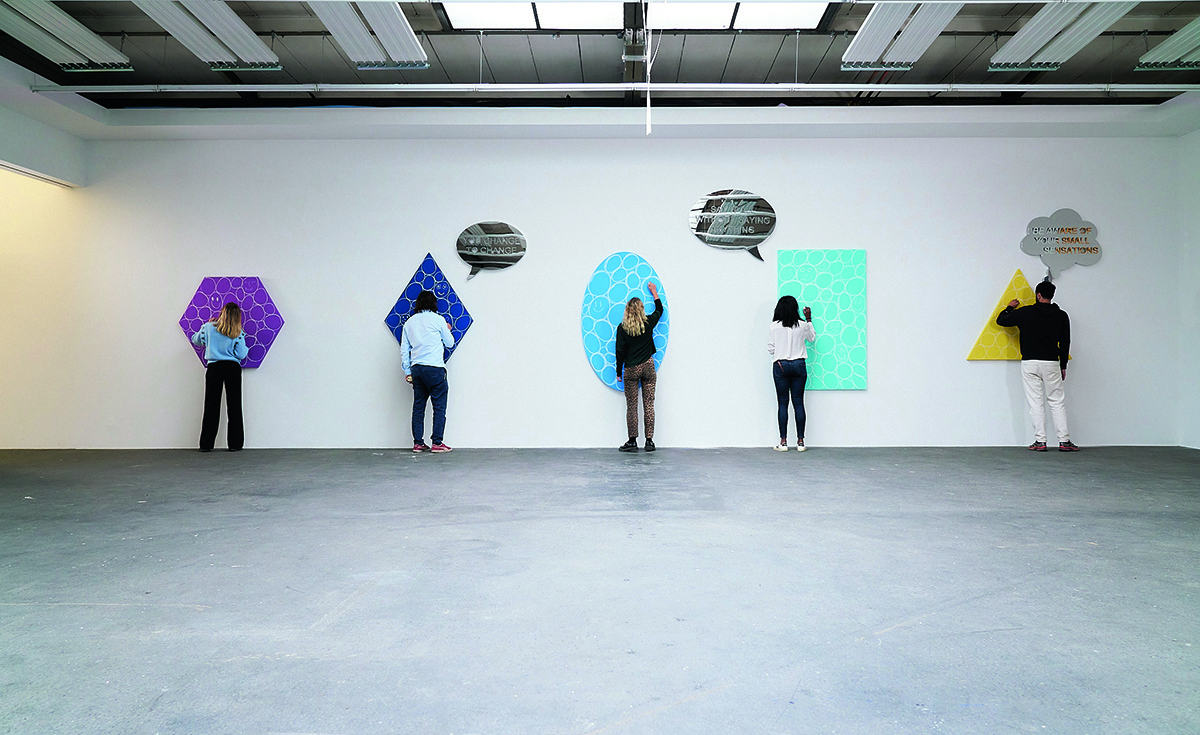

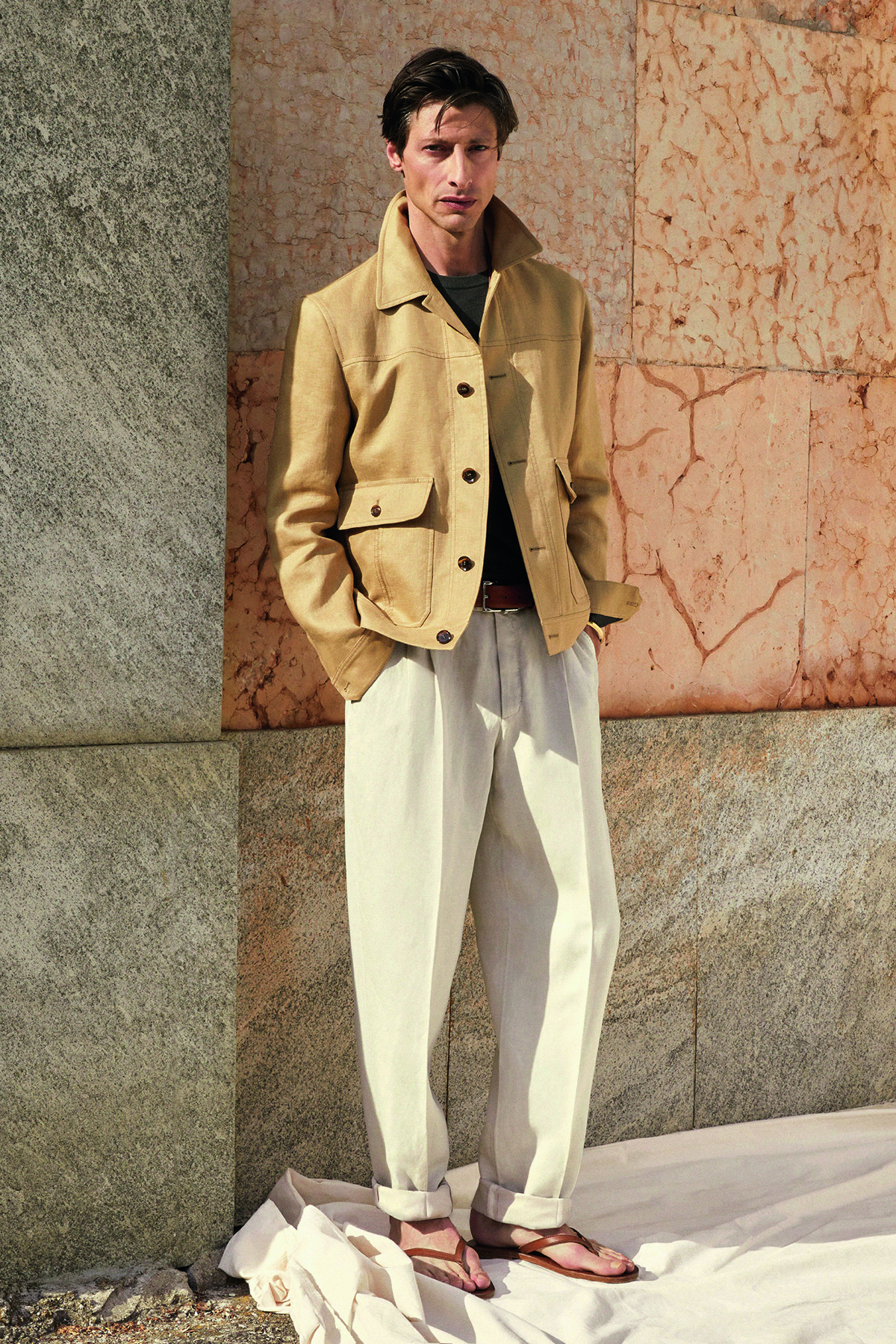

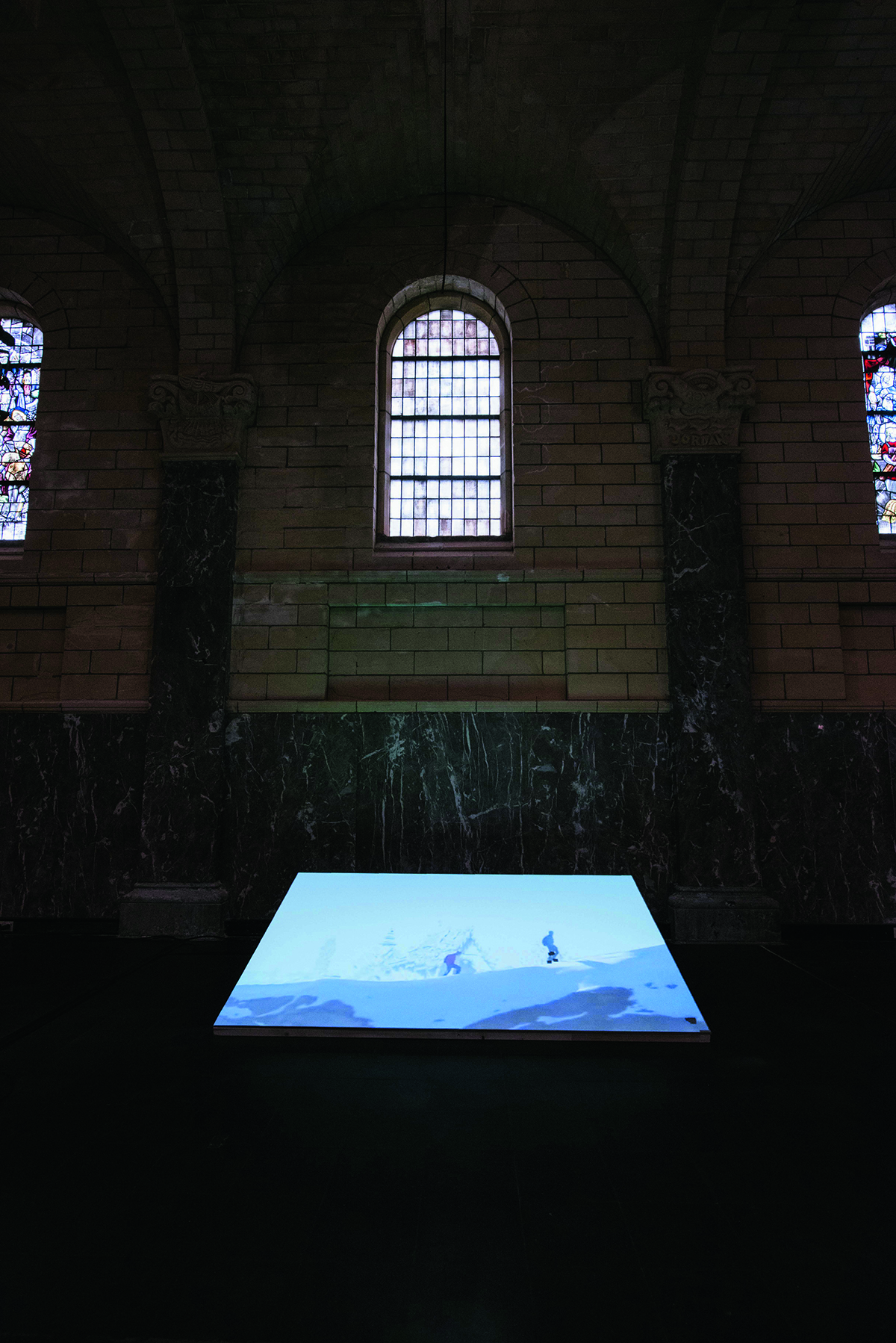

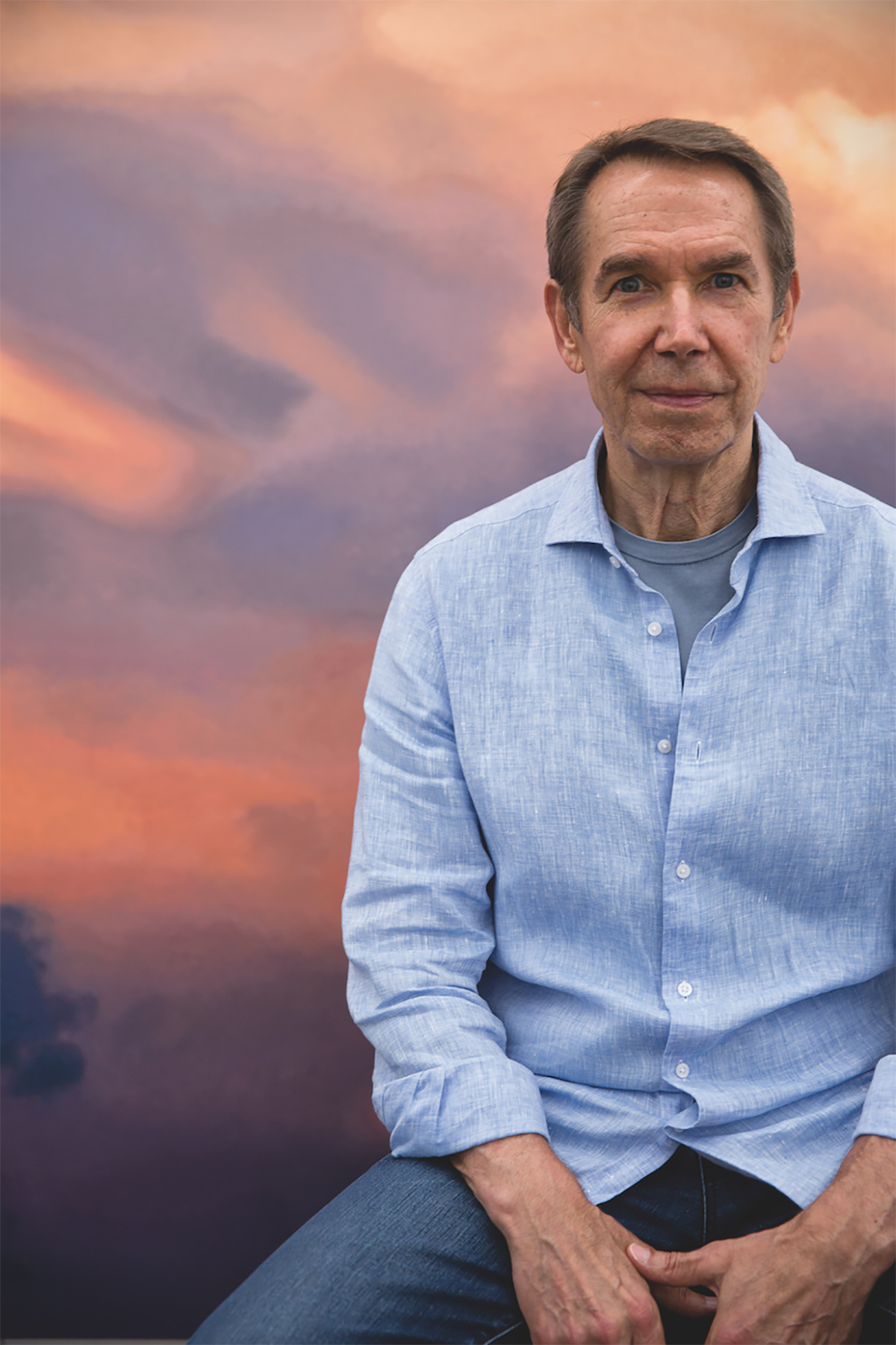

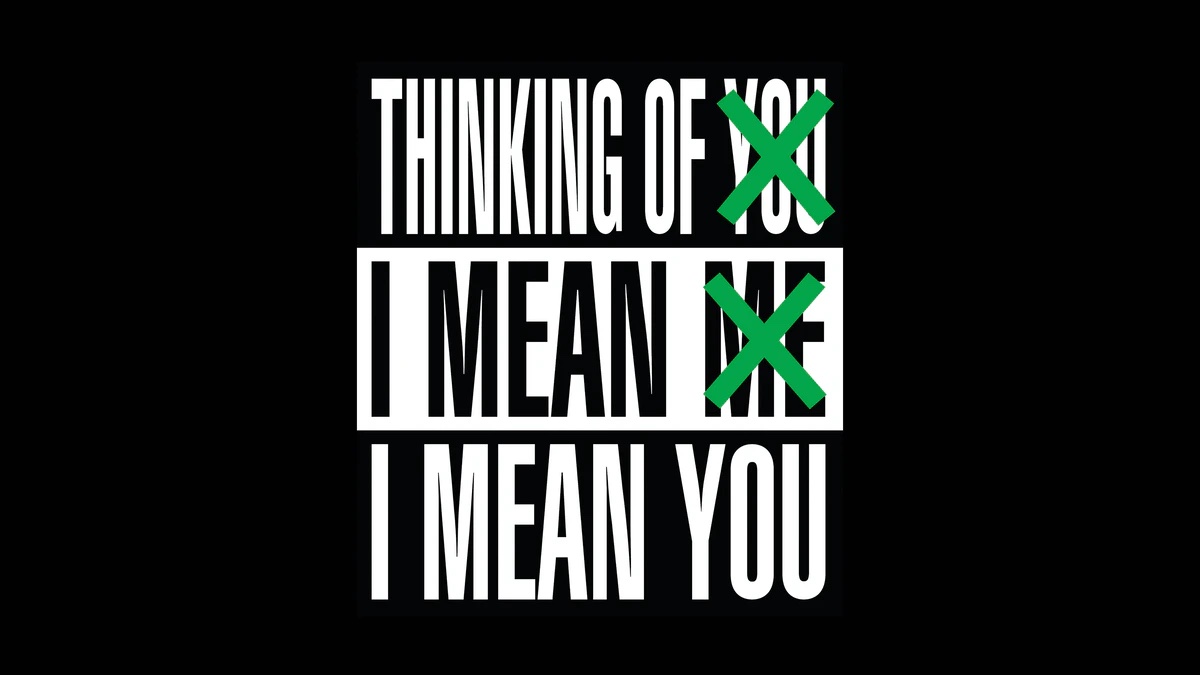

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice