Idris Khan, ‘I Thought We Had More Time’, print created to raise funds for Ukraine

Sir Lawrence Freedman is one of the world’s foremost scholars of strategy and war. Here he answers our questions on the geopolitics around the Russian invasion of Ukraine and potential outcomes

Sir Lawrence Freedman

LUX: Was the West culpable of negligence and/or triumphalism in its policies towards the former Soviet Union/Warsaw Pact territories after the fall of the Berlin Wall, during the 90s?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: Within Europe at least, the end of the Cold War was a victory for liberal capitalism. The members of the Warsaw Pact plus the three Baltic states joined Western institutions (NATO/EU) and followed liberal democratic/ rule of law policies. This was also the case with the former Yugoslavia. In a few cases there has been backsliding into more illiberal ways, notably with Hungary and Poland, but by and large this has worked well. These countries are more prosperous and secure than they would have been outside these institutions.

This is the other side of the coin to ‘the NATO was wrong to push for enlargement’ narrative. As someone who was engaged in these issues at the time, and was not a great fan of enlargement, it was hard to avoid the strength of feeling in former Warsaw Pact countries that they wanted to be protected against some future Russian resurgence. They now feel vindicated in this view. Without gathering all these countries together in a single alliance there was also a risk of antagonisms developing among these countries.

For the first decade after the Cold War this was not a big issue with Russia (NATO entered into a special partnership with Russia in 1997 to prevent tensions). In retrospect the biggest failure was to advise a short and unregulated transition to a capitalist system which led to gross inequalities, cronyism and corruption.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: Vladimir Putin started off wanting to create a mutually respectful and harmonious relationship with the West, but was rebuffed, and swung instead to Russian extreme nationalism. True or false?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: Putin was not rebuffed. There were serious efforts in the early 2000s to work with Putin and consult Russia during this period. It took until 2007 for Putin to start to break with the West, when he made a speech at the Munich Security Conference condemning Western policies. He had two lots of concerns. The first reflected his view that Western countries did not follow their own rules when it suited them. His examples were Kosovo in 1999 and Iraq in 2003. The second was his anxiety about the so-called colour revolutions – Rose in Georgia in 2003 and then Orange in Ukraine in 2004-5, that saw popular movements demonstrate against rigged elections and corrupt regimes. This developed into a fear of a comparable movement in Russia, combined with a conviction that they were being manufactured by Western intelligence agencies.

Putin’s approach to exercising influence within Russia but also his views about how others operated was shaped by his background in the KGB and then his later role in its successor, the FSB. He shared the strong view among the Russian elite that Russia was, and must be treated as, a great power. As he became more antagonistic towards the West after 2005, which was gradual and not sudden, the nationalism increased. But the biggest driver has been his determination to protect his own power, which has also led to the increased oppression of oppositional elements at home.

LUX:At this stage, post-invasion, can you draw any parallels with any other invasions in modern European history?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: Not really. It is not on the scale of Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa of 1941 and far more substantial than the Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and also the operations against Ukraine in 2014.

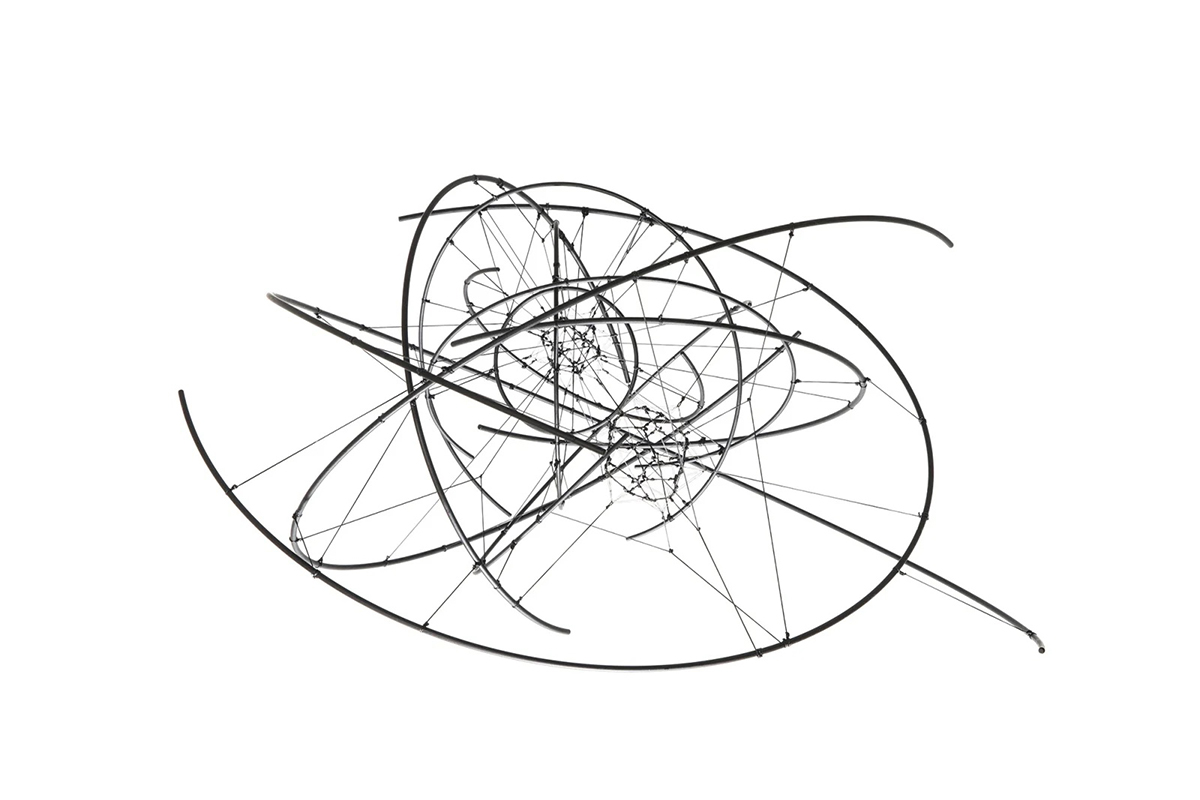

Tomás Saraceno, ‘Zonal Harmonic 2N 55/11’, part of the ‘Artists for Ukraine’ Exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

LUX: Neither Ukraine nor Russia will suffer an outright defeat, so this war will end with negotiation. How can negotiations succeed if the principal Russian actors know they will be prosecuted for war crimes once they sign any peace deal? And what can be done about this?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: It depends on what you mean by outright defeat. It has been apparent from the first days of the invasion that Russia could not achieve its basic objectives of conquering Ukraine and installing a puppet government. It is however possible that Ukraine will achieve its core objective of getting Russian forces to withdraw from its territory, either through force of arms or diplomacy. Militarily Russia has already suffered one major defeat by being forced to withdraw from Kyiv and has now lost 40 percent of the territory taken in February. Russia is now gearing up to take and hold all of the Donbas which is the battle now just starting.

The war crimes issue is important for the long term but not so relevant to the short term. The key issues in a negotiation between Russia and Ukraine will be security guarantees and, most important, who holds what territory. The big issue for the external actors, including the EU and NATO countries, will be what happens to economic sanctions if Putin stays in power.

It is entirely possible that if either Russia acquires a chunk of land that it believes is defensible or if Ukraine pushes Russian forces back that there will be at best a temporary cease-fire and no proper peace settlement. In which case sanctions will stay and war crimes investigations will continue.

LUX: How likely is leader change in Russia in the short term?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: It is certainly possible but Putin has a firm grip on the levers of power in Moscow and he has put his people in all the key positions. His fear of popular movements has led to the suppression of independent media and free speech, and opposition figures have either been killed or imprisoned or pushed into exile.

A self-evident Russian defeat in Ukraine, reinforced by the numbers of killed and wounded, combined with the economic pressures resulting from sanctions, is likely to produce strain on the structures of power. We have already seen the start of purges as Putin blames others for his setbacks. These may start to produce a reaction amongst members of the elite. It is hard to see how Putin’s position could not be affected. The war was his decision and it has already gone badly wrong. But this is an area in which it is hard to make firm predictions.

Sabine Hornig, ‘It requires’, part of the artists for Ukraine Exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

There have been rumours of poor health, most recently thyroid cancer. A medical condition could either oblige him to stand down or provide an excuse should he be forced to do so.

One should not assume that a new regime would be more liberal or technocratic. A failure in Ukraine would produce a backlash from the extreme right as well as from remaining moderates.

LUX: There is no world without Russia, says Putin, and Putin believes he is Russia. Does that mean that he will do what Hitler would have dreamed of, and unleash nuclear apocalypse, rather than be removed? And would his orders be obeyed?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: I don’t think so. This is obviously everyone’s nightmare but he would need others to implement the decision and there is still sufficient rationality remaining in the system for this to be allowed to happen. Signs that he was contemplating such a measure might even be a reason for those opposed to him in the elite to mount a coup.

NATO has been very careful not to get directly involved in the fighting, which would provide Putin with most grounds for escalation, even while assisting Ukraine in other ways. Putin is already getting his vengeance on Ukraine for resisting his aggression by attacking its infrastructure, economy and civil society.

LUX: Given how deeply the links between oligarchs and the state run, how can sanctions be lifted, even if there is a negotiated settlement?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: For reasons given above I think it will be difficult to lift sanctions while Putin is in power unless it is absolutely essential to confirming a satisfactory settlement. Moreover the negative effects of conflict on the Russian economy are not only the result of sanctions. There is a now a European policy to reduce energy dependency on Russia and many companies have either abandoned Business interests in Russia or will not now consider new investments.

LUX: It’s 2025. What do relations between Russia, Ukraine and the West look like?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: Relations between West and Ukraine will be closer. Whatever happens now in the conflict, the bulk of Ukraine will not be under occupation. I suspect it will be too early for membership of EU and NATO. These require demanding transitions, and will require Ukraine to deal with corruption. There will need to be a massive reconstruction programme in Ukraine to repair damage and help the economy recover. As for Russia it all depends. I would like to think that Putin will be gone so that there can be a start of a new relationship but lots must now happen for that to be the case. Either way it will take a long time for Russia-Ukrainian relations to recover. It will be very hard for Ukrainians to forgive what has been done to their country.

LUX: How severe will be the economic shock of this war be, beyond Russia and Ukraine?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: The economic shock is going to be severe. The war already risks pushing the West into recession next year. Food and energy costs are going up around the world, with poor countries often the worst hit. It is worth recalling that the Arab Spring of 2011 was triggered by rising food prices. The longer the conflict lasts the worse the economic hit, especially if it continues for more than six months and into next winter.

Olafur Eliasson, ‘Flatland Light’, part of the ‘Artists for Ukraine’ Exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery

LUX: Will China, the US or Europe gain or lose more, geopolitically, from the war?

Sir Lawrence Freedman: When this started it was assumed by many that China would gain because it would draw the US back into Europe with less time for Indo-Pacific. In addition, China had forged a virtual alliance with Russia just before the war began. At the same time it has had decent relations with Ukraine. From the start of the war it has talked about the need for peace but has not done much about it – for example offer services as a mediator. It has abstained at UN votes. It has supported some Russian anti-American propaganda points and argued strongly against economic sanctions (which it dislikes for other reasons). It would find an evident Russian defeat an embarrassment as it would undermine a partnership in which it had invested politically (if not economically). Beijing is also aware of lessons being drawn about the threat China poses to Taiwan because of the Russian experience in Ukraine.

The US has largely handled the war effectively. It has pulled NATO together effectively and has worked hard to support Ukraine without taking risks of being drawn into the war itself. It has reminded the world – post-Trump – that the US can be an effective foreign policy actor. It has acquired a lot of intelligence about Russian military capabilities. Assuming that Russia is a diminished power after this war, then US strategic calculations become easier.

Read more: GreenBiz’s Heather Clancy On Corporate Climate Action

The EU has had a less happy time, mainly because the conflict has exposed the way in which a number of member states, but in particular Germany, allowed themselves to become dependent on Russia for energy supplies. Also Germany was risk averse when it came to supporting the Ukrainian militarily and with France offering itself as a mediator. Macron could justify his efforts to keep the conversation going with Putin just in case it was possible to help with peace talks and humanitarian relief but he has so far little to show for the effort.

The UK has had by and large a good war. It has pursued close relations with Ukraine since 2014 and played an important role in training Ukrainian forces, and was the first country to respond to the current crisis (after its intelligence agencies called out the risk of an imminent invasion with the US) with weapons supplies. It has continued to take a lead in either supplying weapons itself or encouraging other donors. Less positively it has struggled to take in Ukrainian refugees and has had the role of the City of London as a home for Russian money highlighted, leading to more restrictive measures.

Sir Lawrence Freedman is Emeritus Professor of War Studies at Kings College London