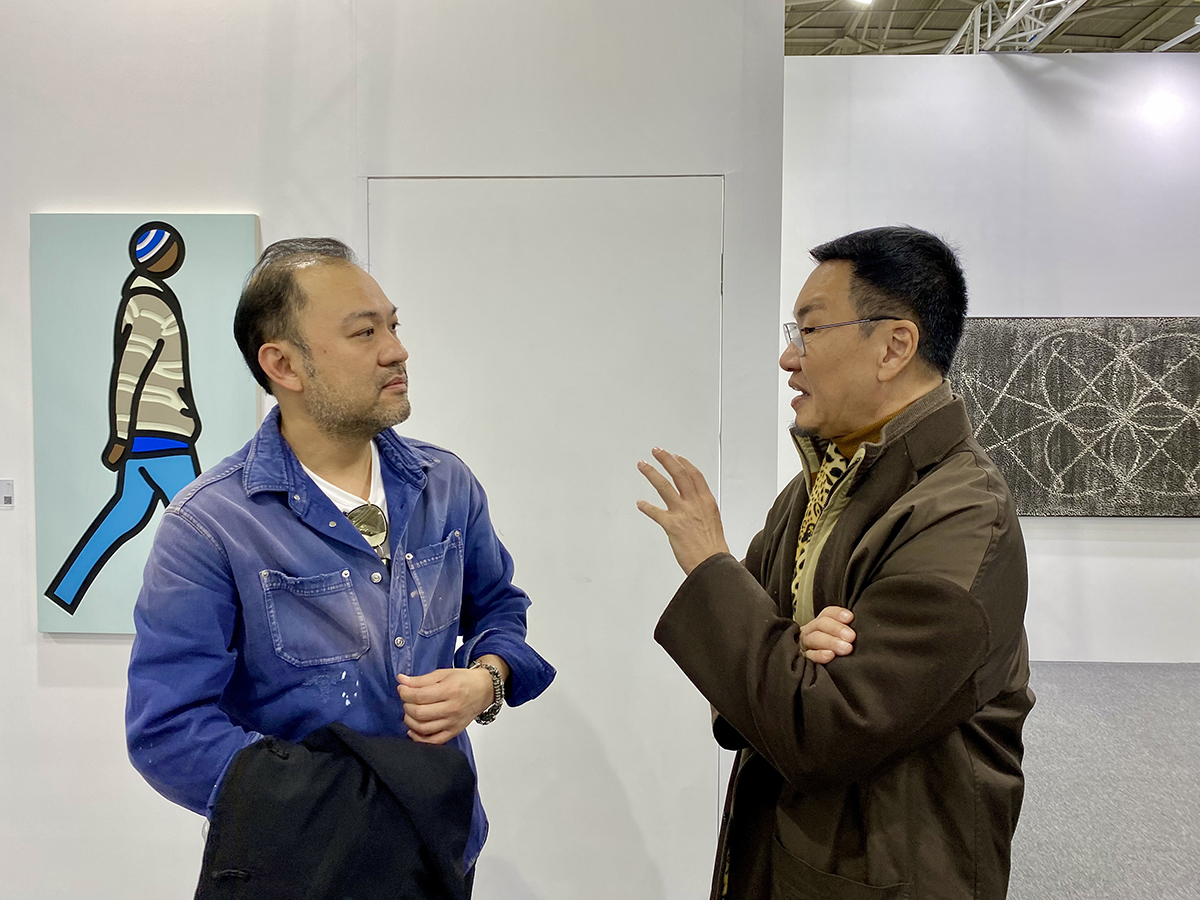

You can find his works on the back of mass-market cereal packets, in leading museums and on sneakers. Some change hands for millions, and others are made in their millions. More than any other living artist, Brian Donnelly, known as KAWS, carries the Andy Warhol mantle of blending high and low art. Darius Sanai meets him in his New York studio

For someone who became a global celebrity out of a kind of exhibitionism, Brian Donnelly seems very discreet when I first come across him. We have arranged to meet in his Brooklyn studio when I am in the city for Frieze New York. I escape the Large Hadron Collider atmosphere of meetings, walk along the green escape of the High Line, New York’s elevated urban park, and catch an L Train Subway from the Meatpacking District, under the East River to Williamsburg in Brooklyn.

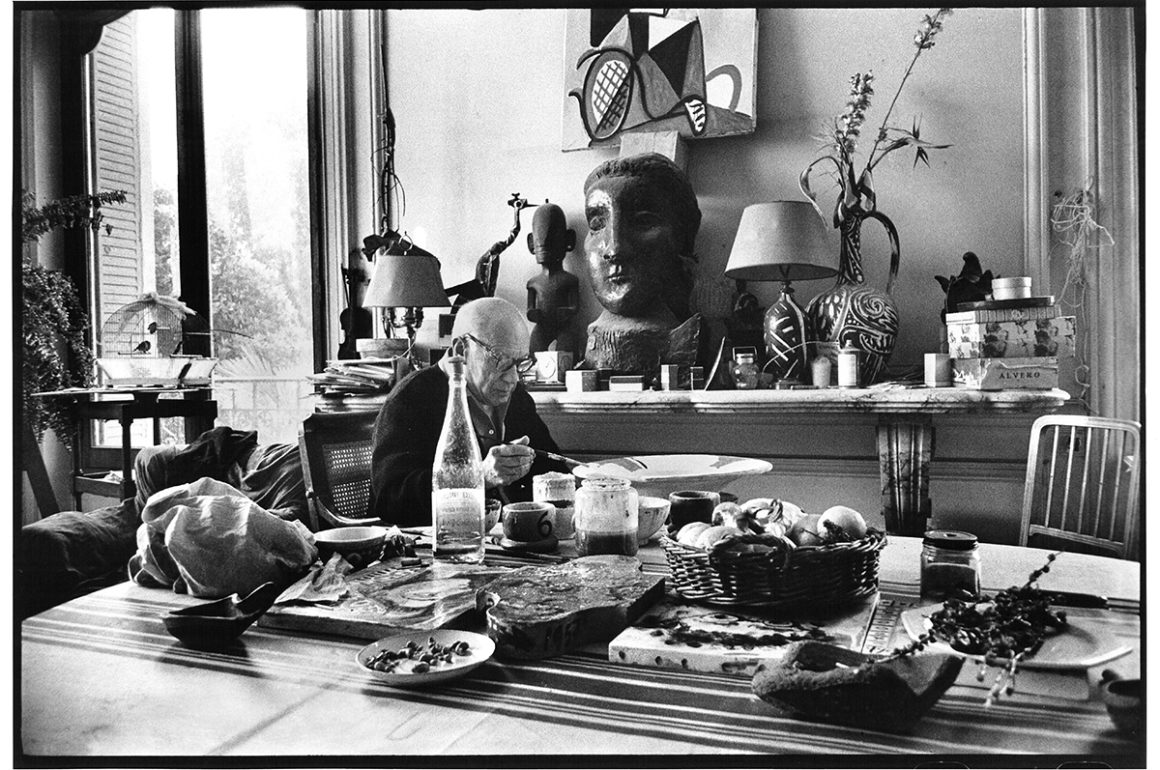

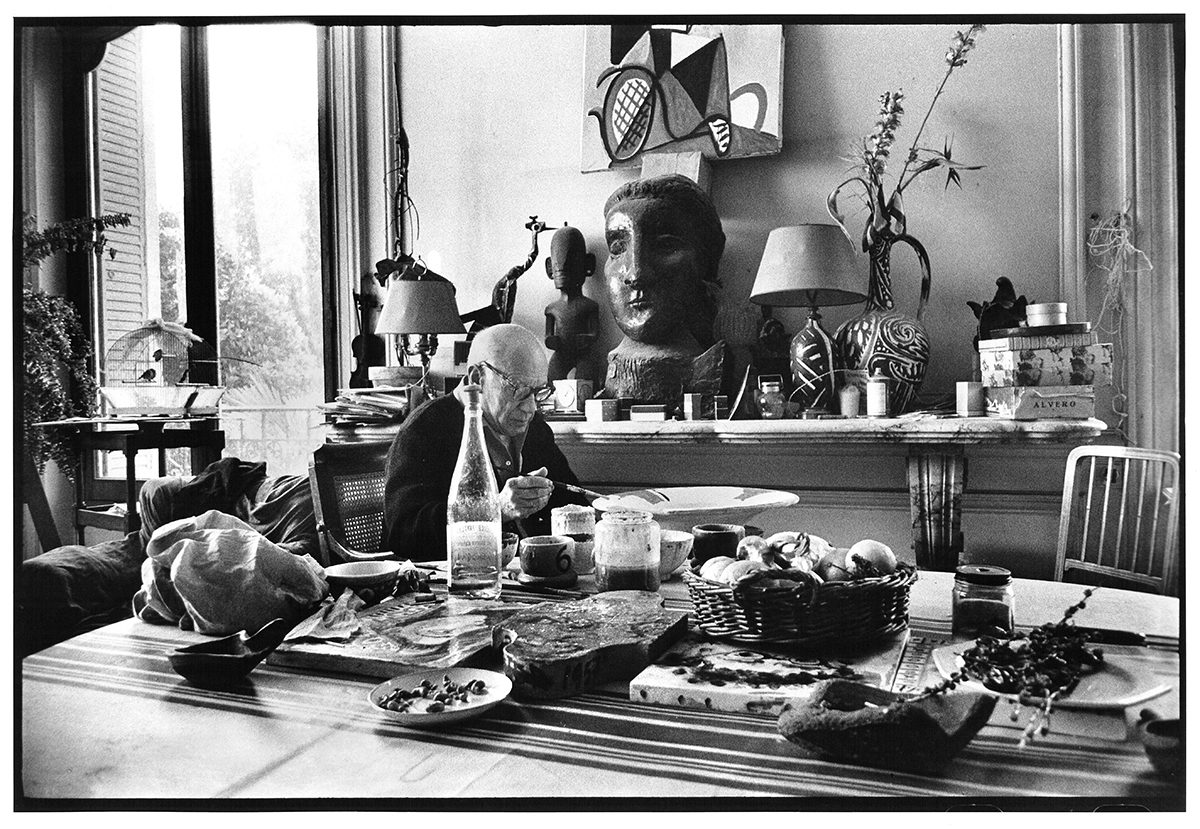

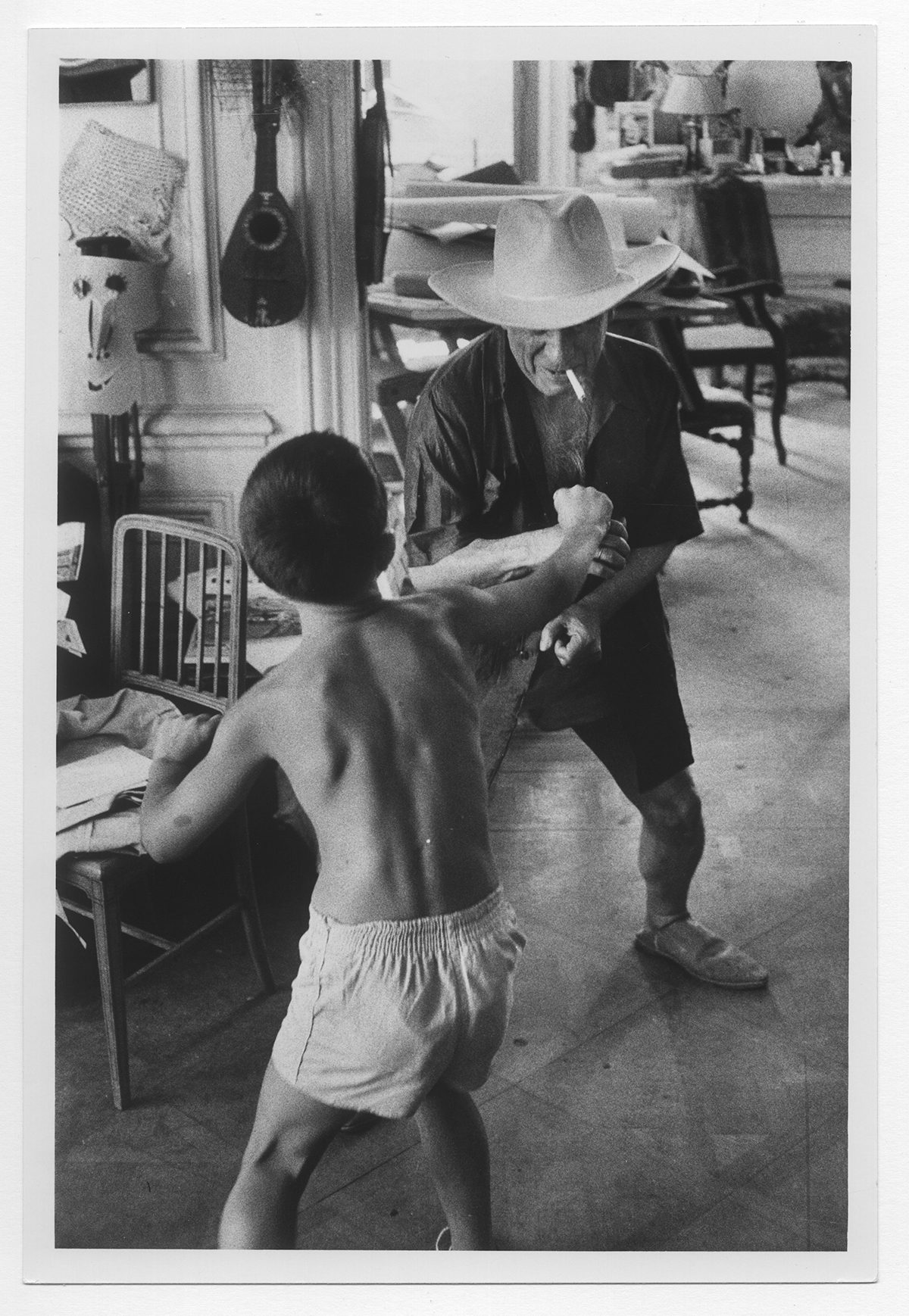

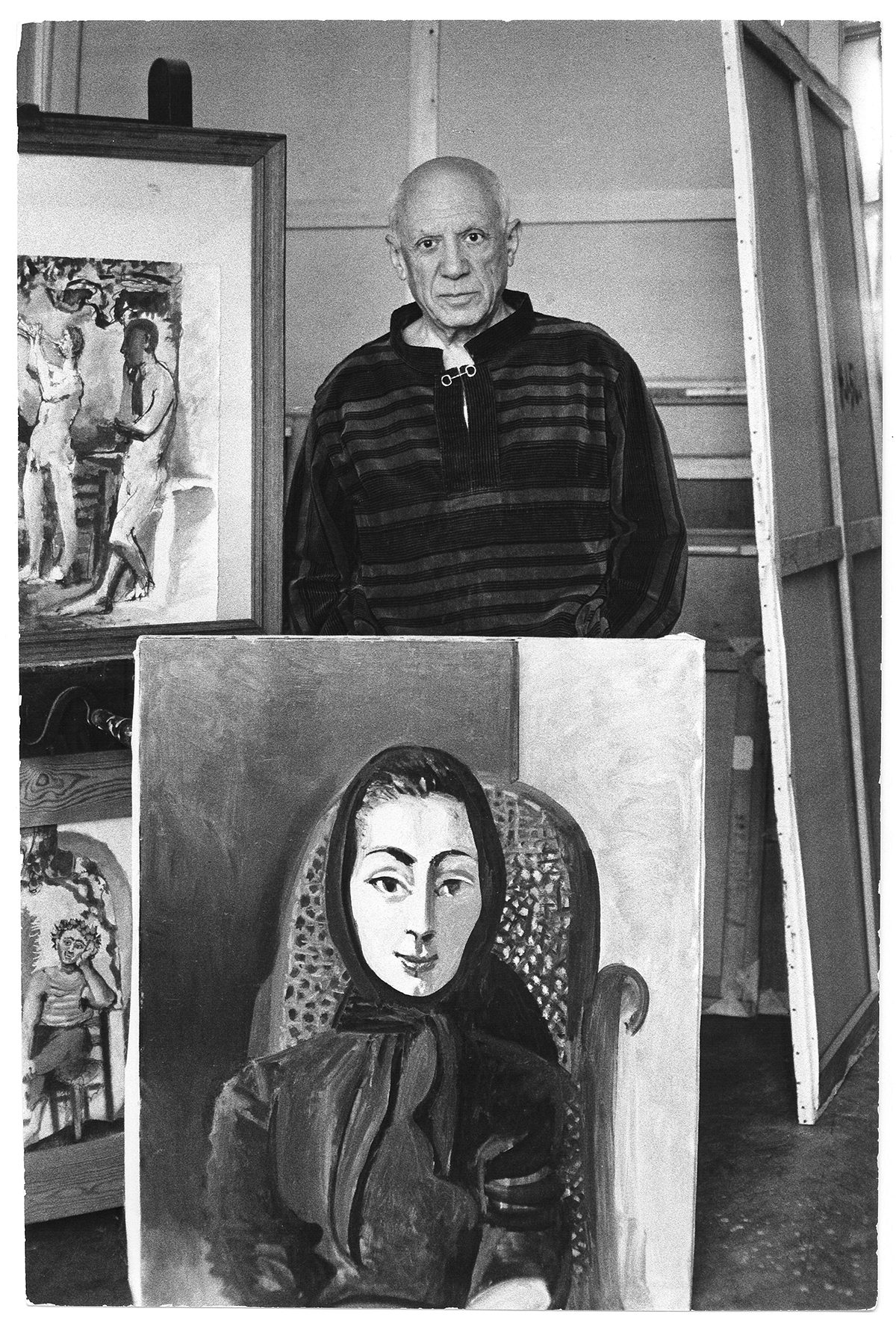

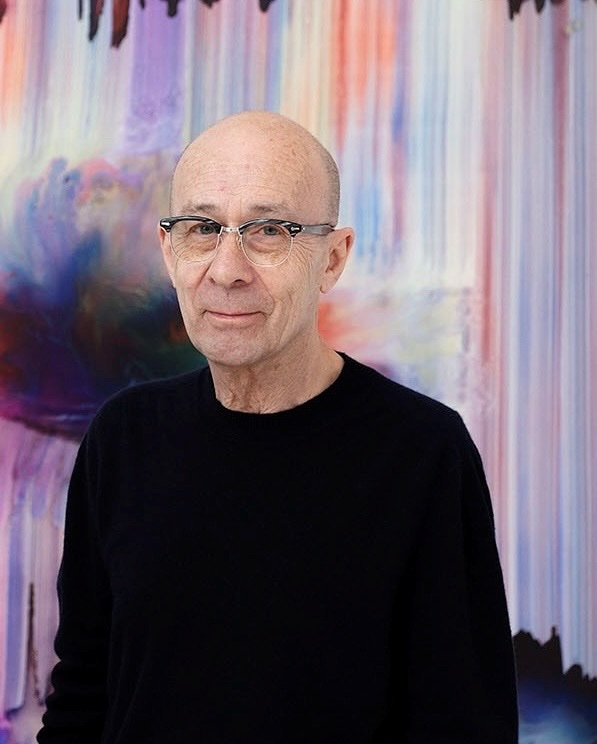

The neighbourhood is bristling with young men in moustaches and shorts, and women in black skinny jeans and camel suede boots. Past a matcha bar, a Pho cafe and a vegan ice-cream joint, I work my way onto a boulevard and a few turns later find myself at a big door leading into a warehouse, unmarked except for a buzzer carrying the door number. The door opens and I walk into a studio space that has Long Island light pouring in through a skylight. Huge canvasses line either side. I have arrived just a few seconds ahead of our appointed time, and a few seconds later a door in the wall opens and Brian Donnelly, or KAWS, says a quiet “Hi” and asks if I would like to follow him upstairs. He is wearing a black T-shirt and jeans, in contrast to my white shirt and white linen trousers. His sneakers are white, his cap black, glasses black- framed. He is polite and welcoming, very correct, quite reserved. He becomes animated when speaking about the art on his walls (mostly by 20th-century artists), but isn’t one for small talk.

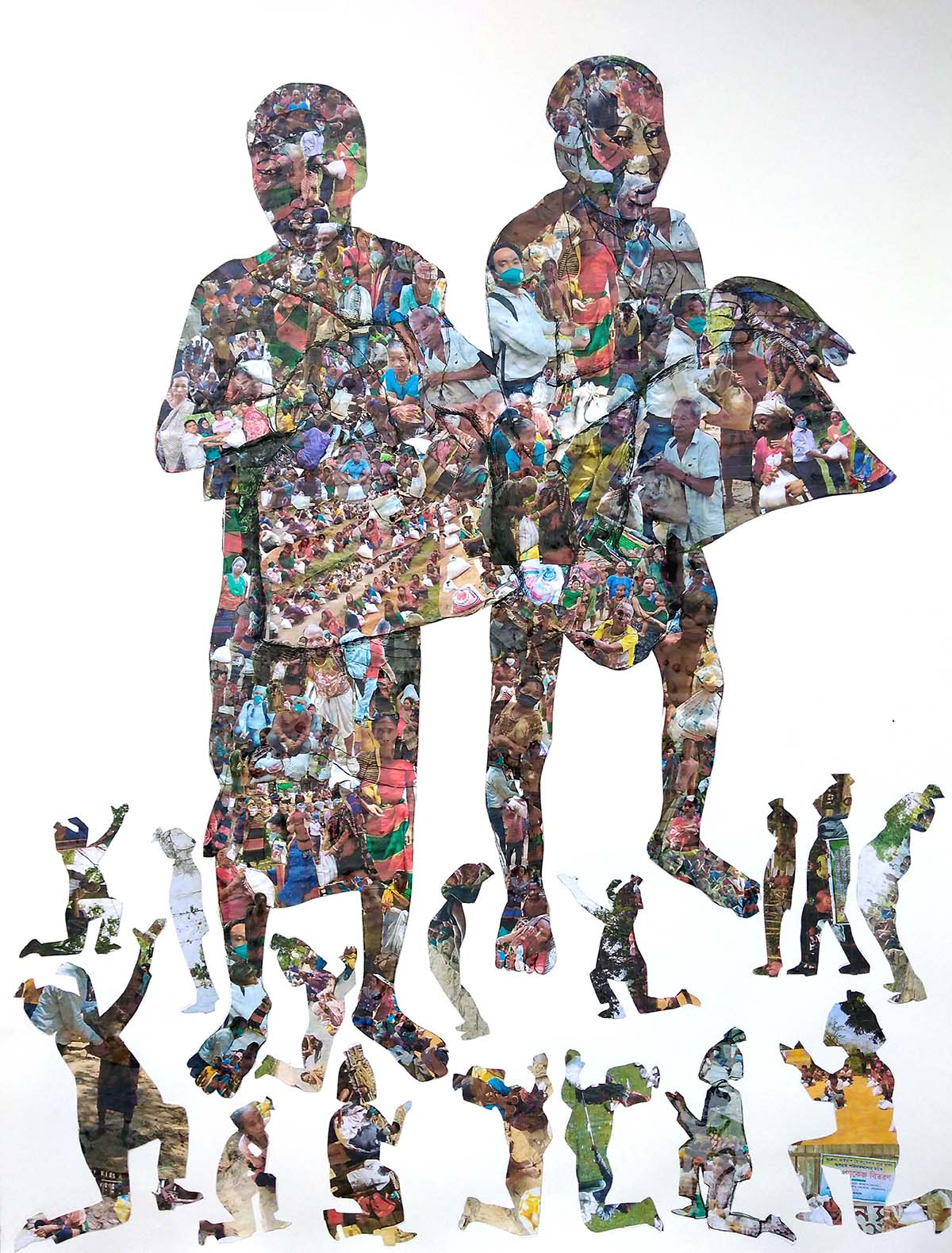

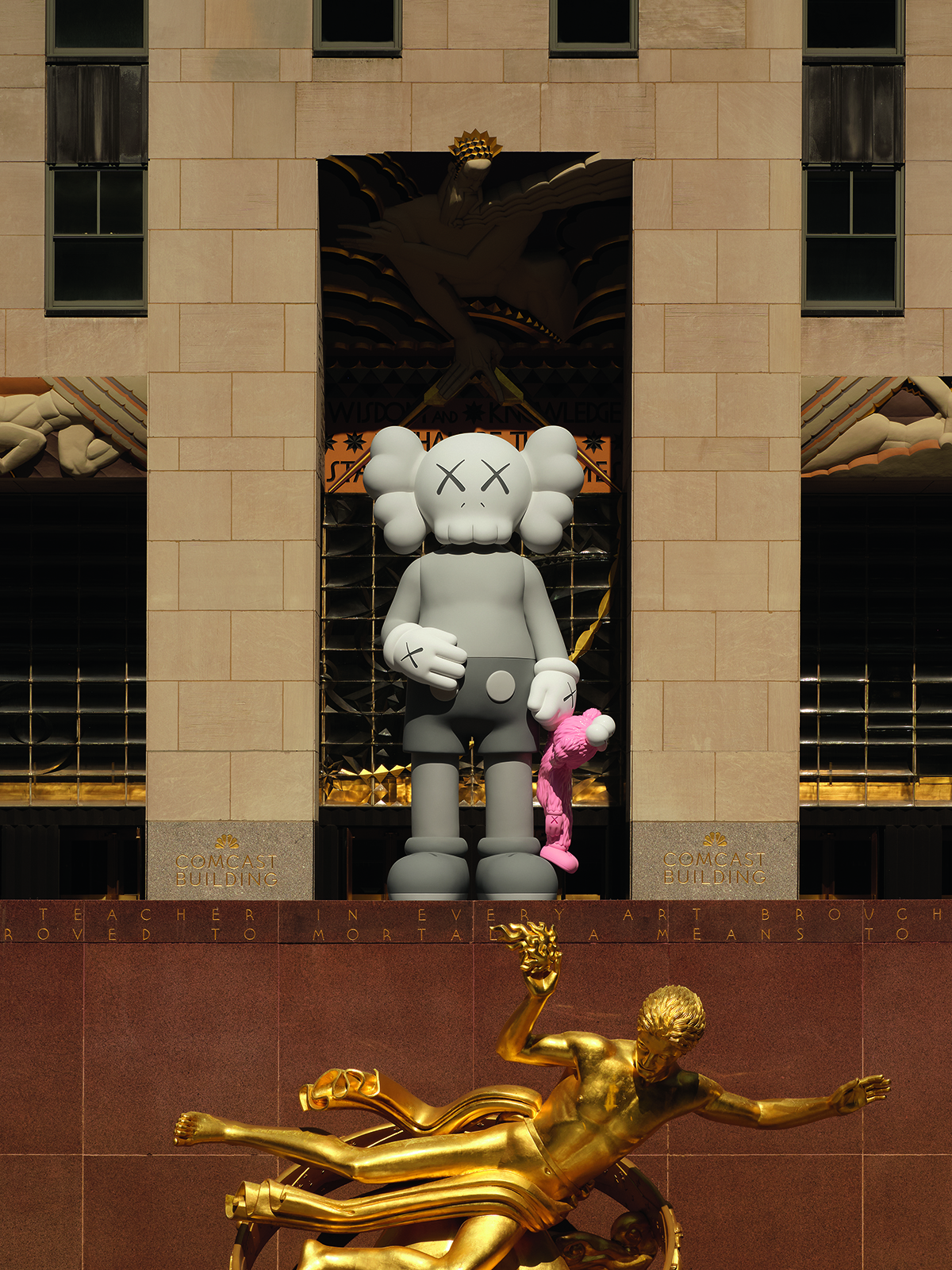

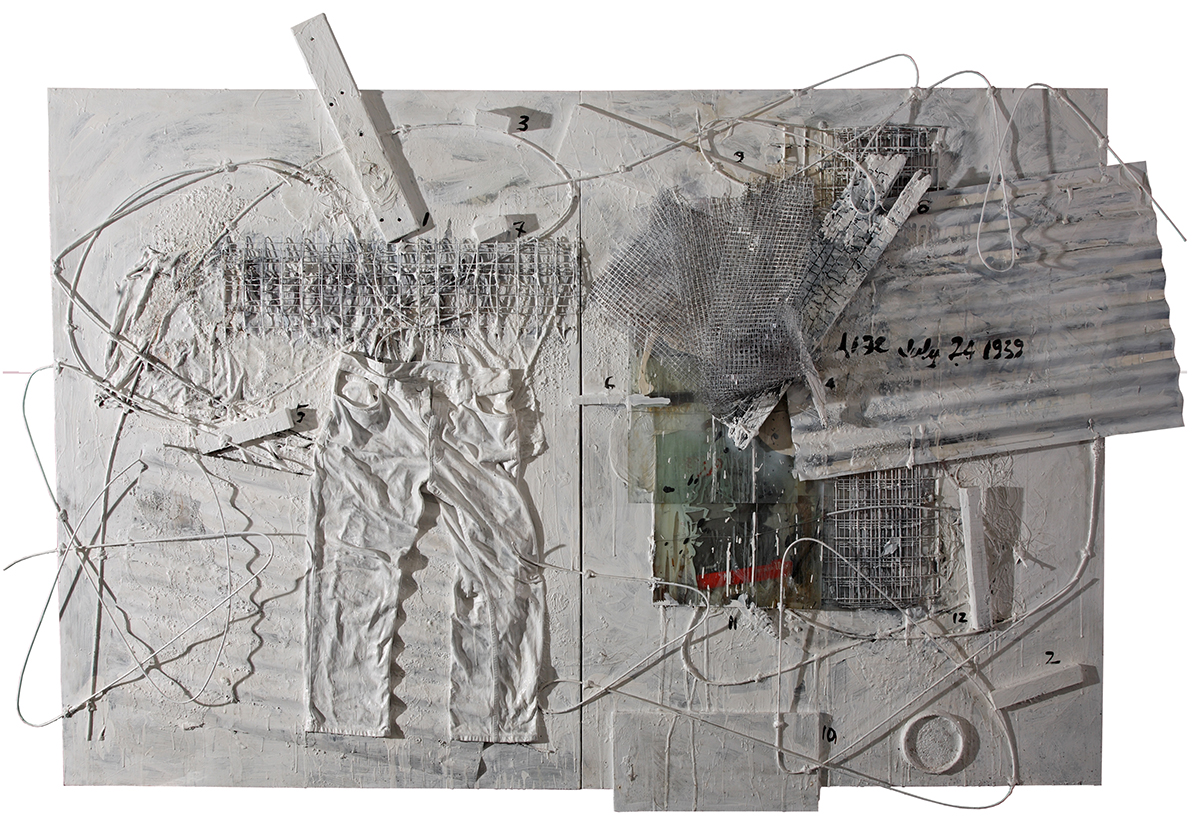

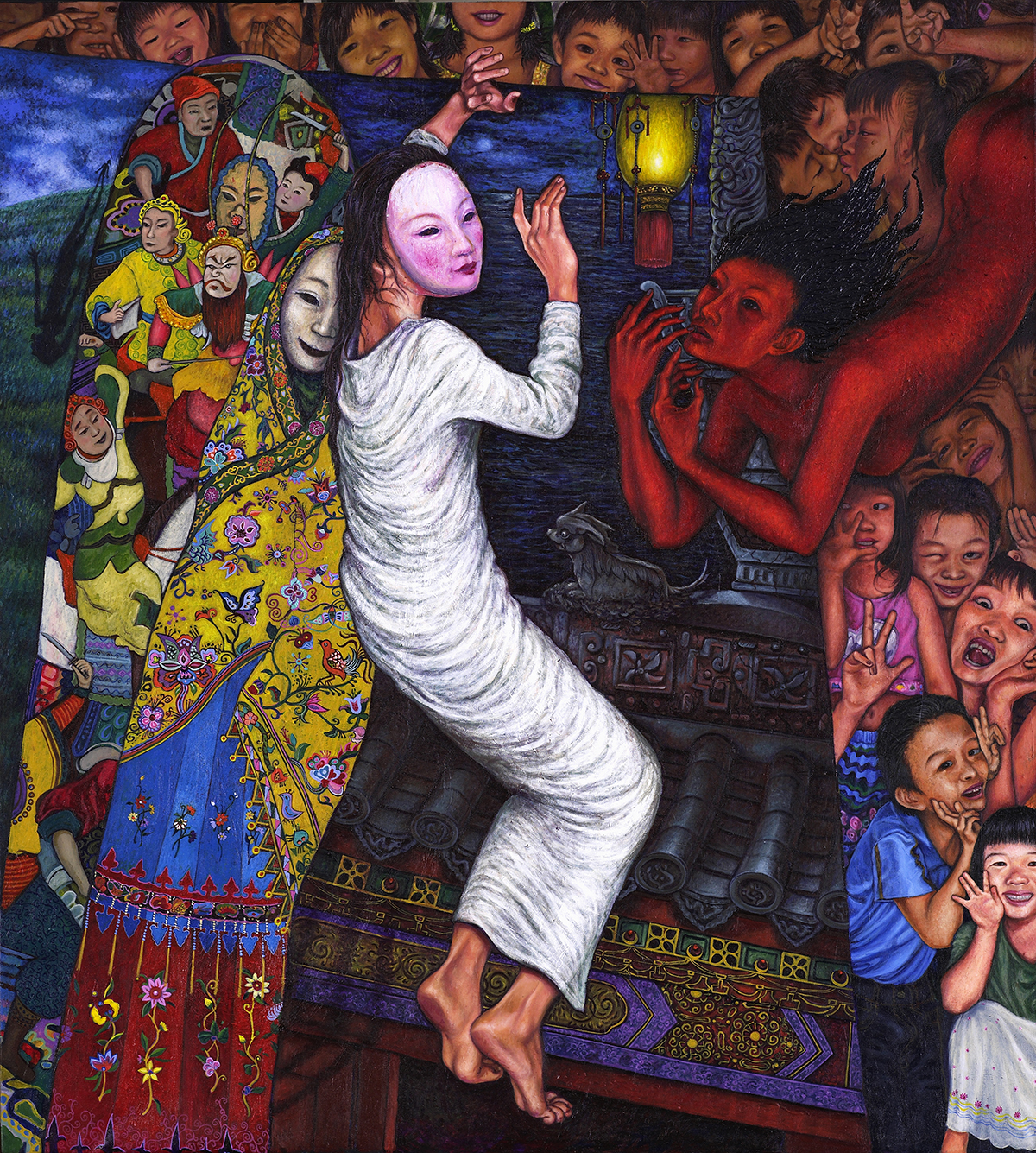

SHARE, 2021, by KAWS, Rockefeller Center, New York

If that is a bit of a surprise, it is because there can be few things more “out there” than making your name as an artist by redecorating, without permission, walls and other public spaces as a spray-painting street artist, as Donnelly did in the 1990s. That’s where his tag, KAWS, came from. A skateboarding guy from Jersey City, New Jersey, he went to art school in New York and found that his distinctive characters and slightly bleak, subversive style quickly gained a following.

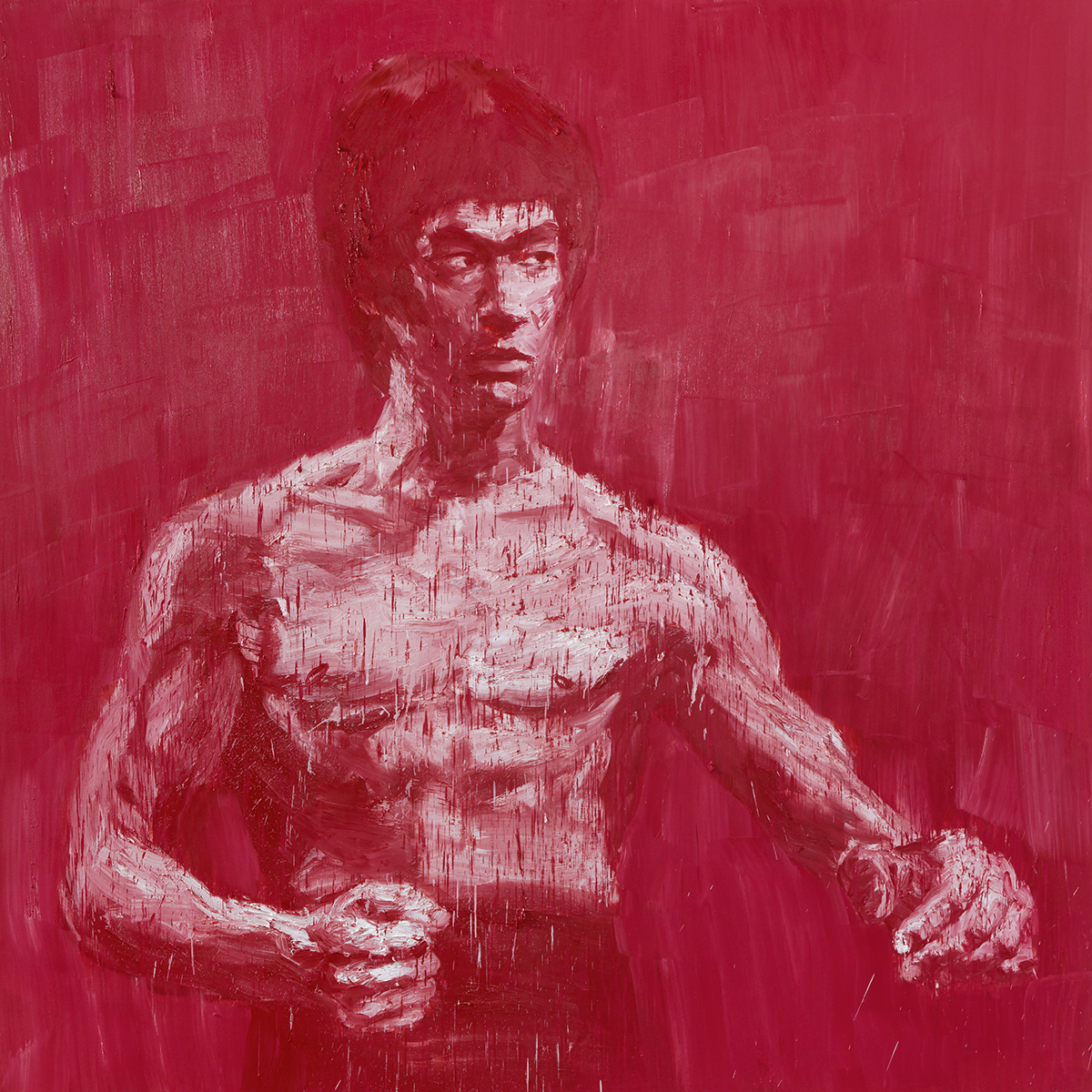

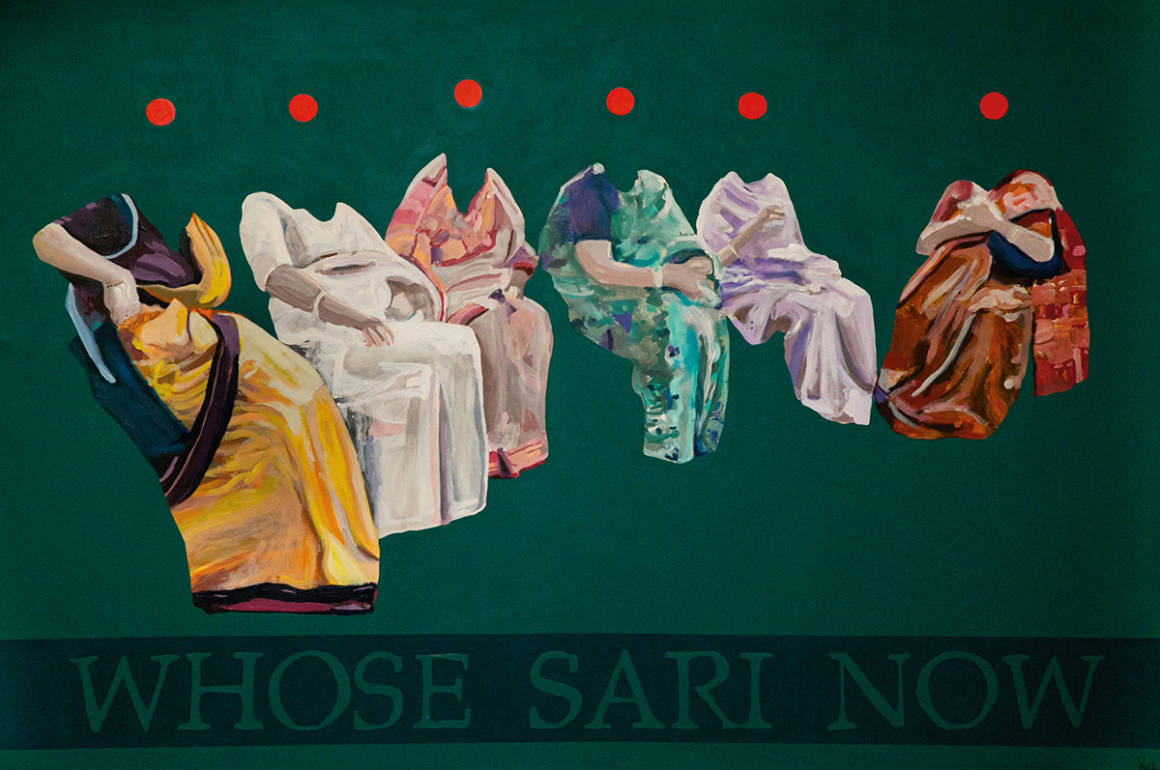

Today, Donnelly’s trademark figures, sculptures and paintings, with Xs for eyes, pervade all areas of public consciousness. Donnelly quickly started collaborating with brands: he has worked with Dior, Supreme, A Bathing Ape, Nike and dozens more, He is also consciously democratic about his collaborations: in 2021 he created cereal boxes for Reese’s Puffs, one of the best-selling cereals in the US. In 2019, his work, THE KAWS ALBUM, commissioned and sold by Japanese polymath NIGO, sold at auction at Sotheby’s Hong Kong for US$14.8m.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Speaking with him for few hours, Donnelly came across as calm, thoughtful, private – even reticent, but with a geek passion for the artists and artistic styles he loves. It would take many more meetings to unfurl someone like him, and I never resolved one riddle to my satisfaction. KAWS is an artist, but he is also, like Andy Warhol, to whom he has been compared, something else. It is just hard to say exactly what.

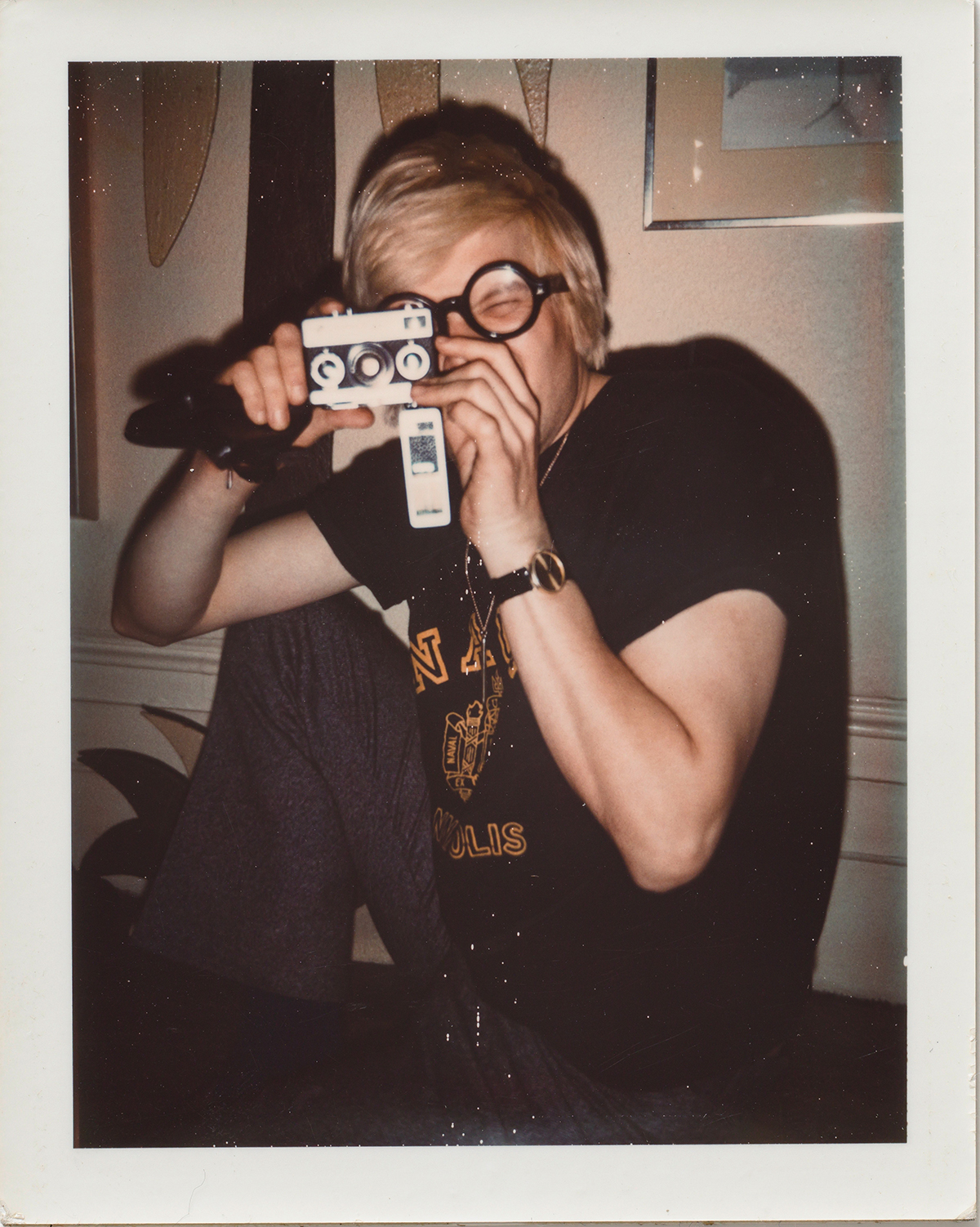

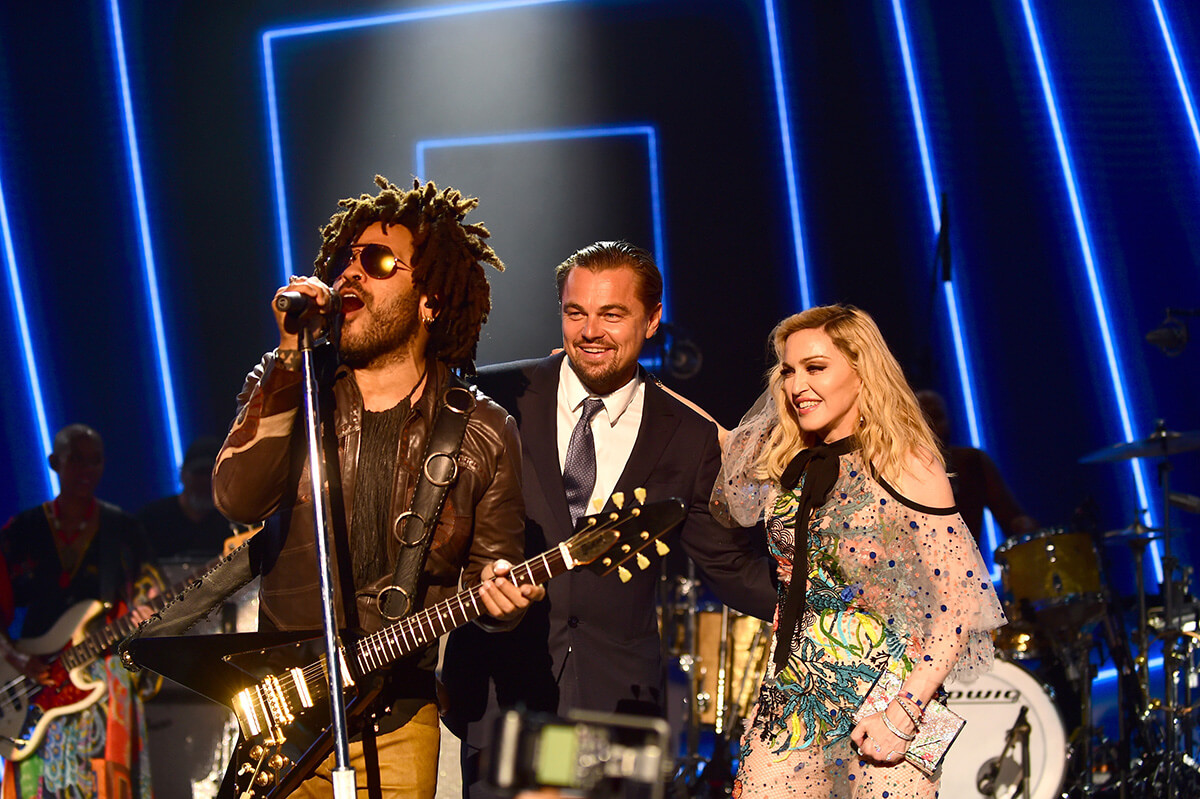

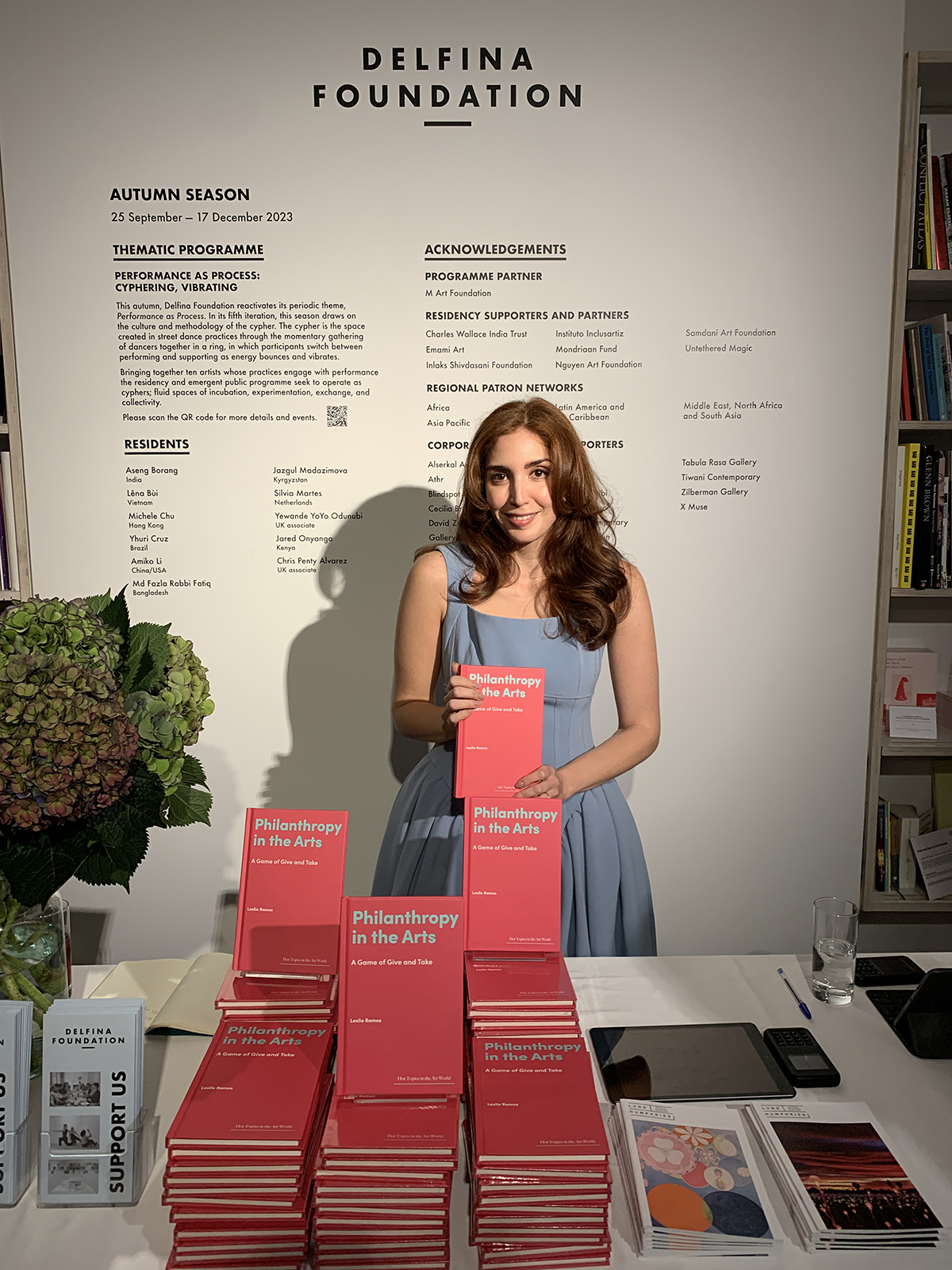

KAWS at his studio

LUX: Your works are now in art institutions around the world. How does that feel?

KAWS: Of course it’s an honour to have work shown, whether it’s in an institution or public art. The reason I make work is communication, to create a dialogue with the audience, and to know that works are on display in different places and contexts is amazing for me.

LUX: When you visit the works, do you observe the audience and their reaction?

KAWS: I don’t often get to visit, but when I see that someone’s interacting with the work it’s a treat. I try to make work that is engaging, and when people stop to have a moment with it I feel like my goal is accomplished.

LUX: When you are creating a work, do you have a reaction in mind?

KAWS: Not at all. For me, I just use the work as a way to get my insights or points of view or feelings in that moment out into the world. I get into different bodies of work in different ways.

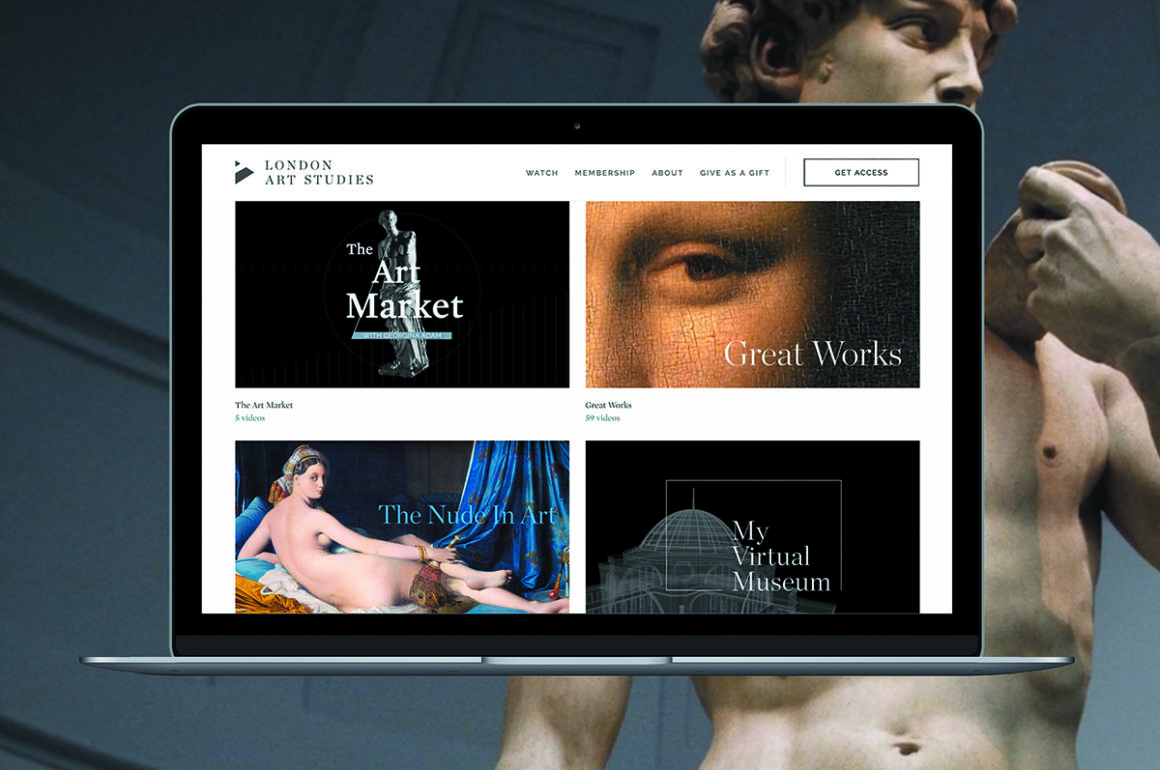

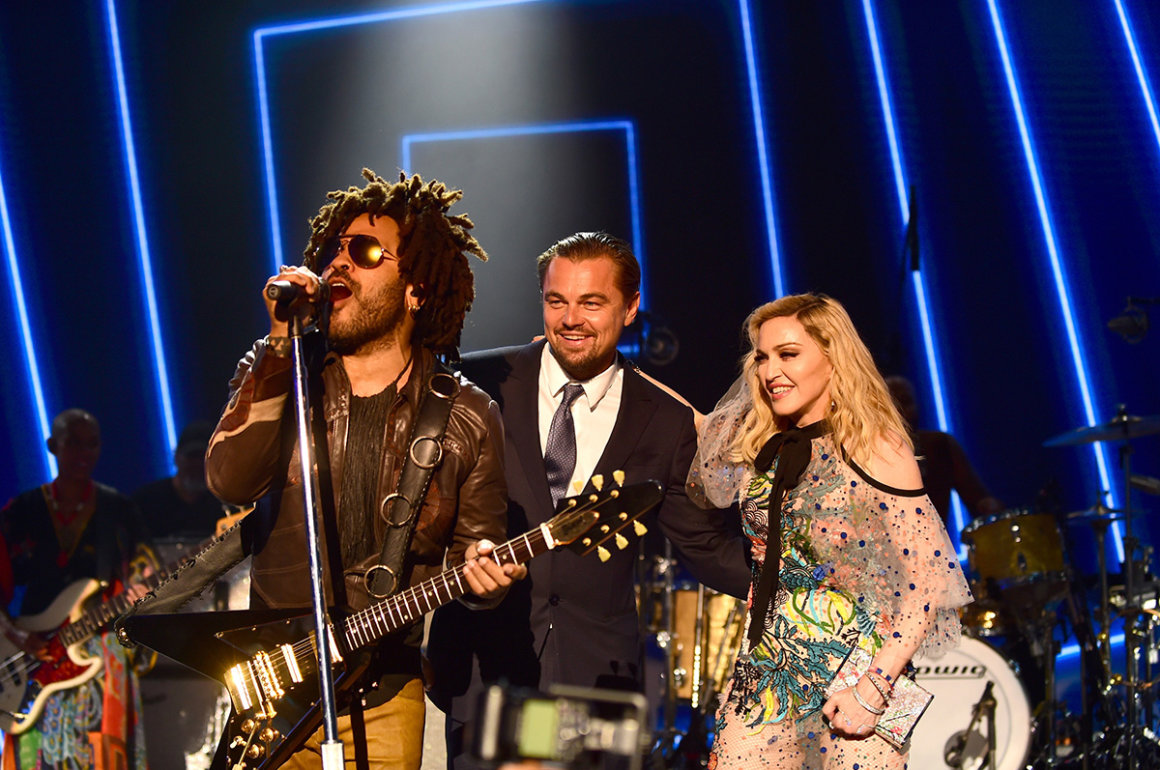

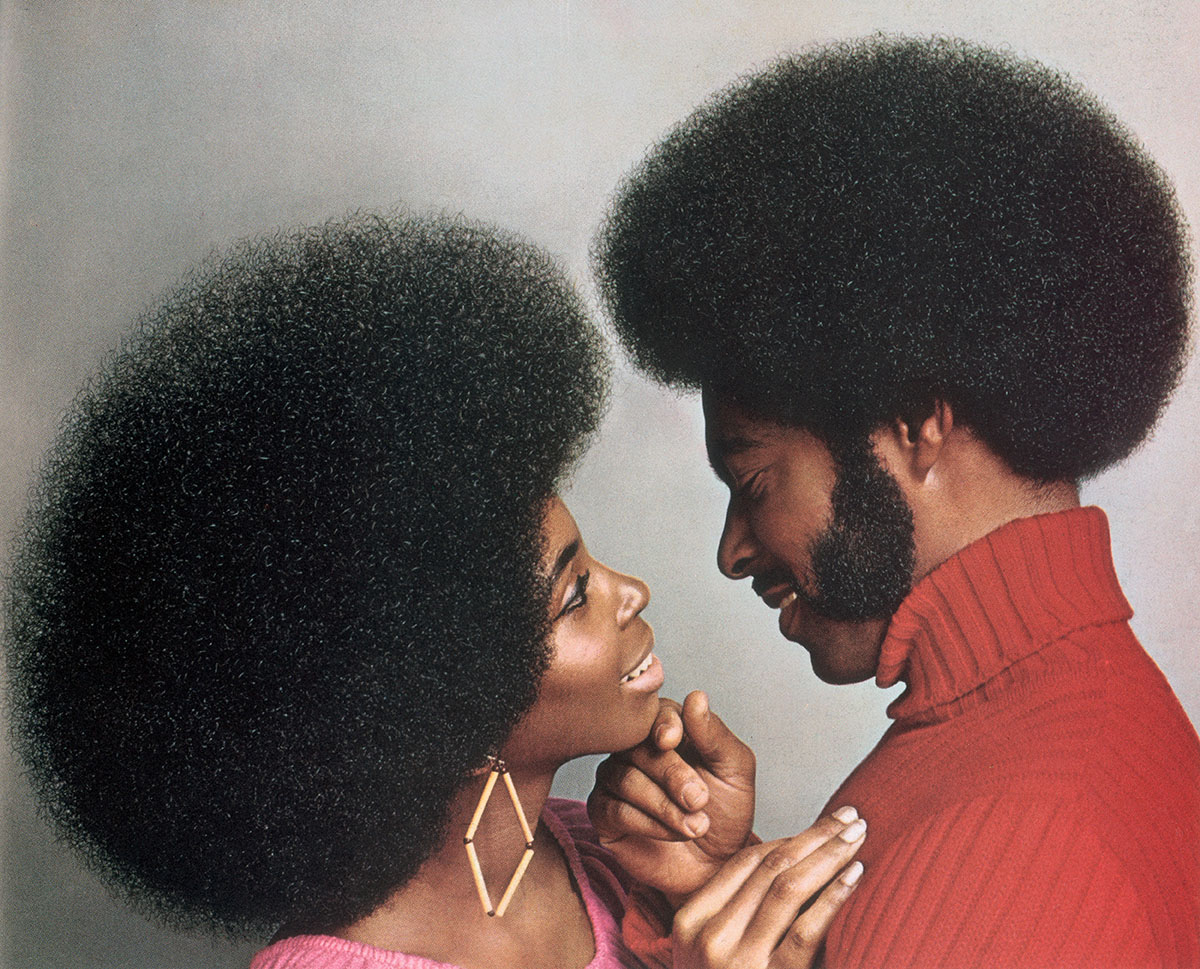

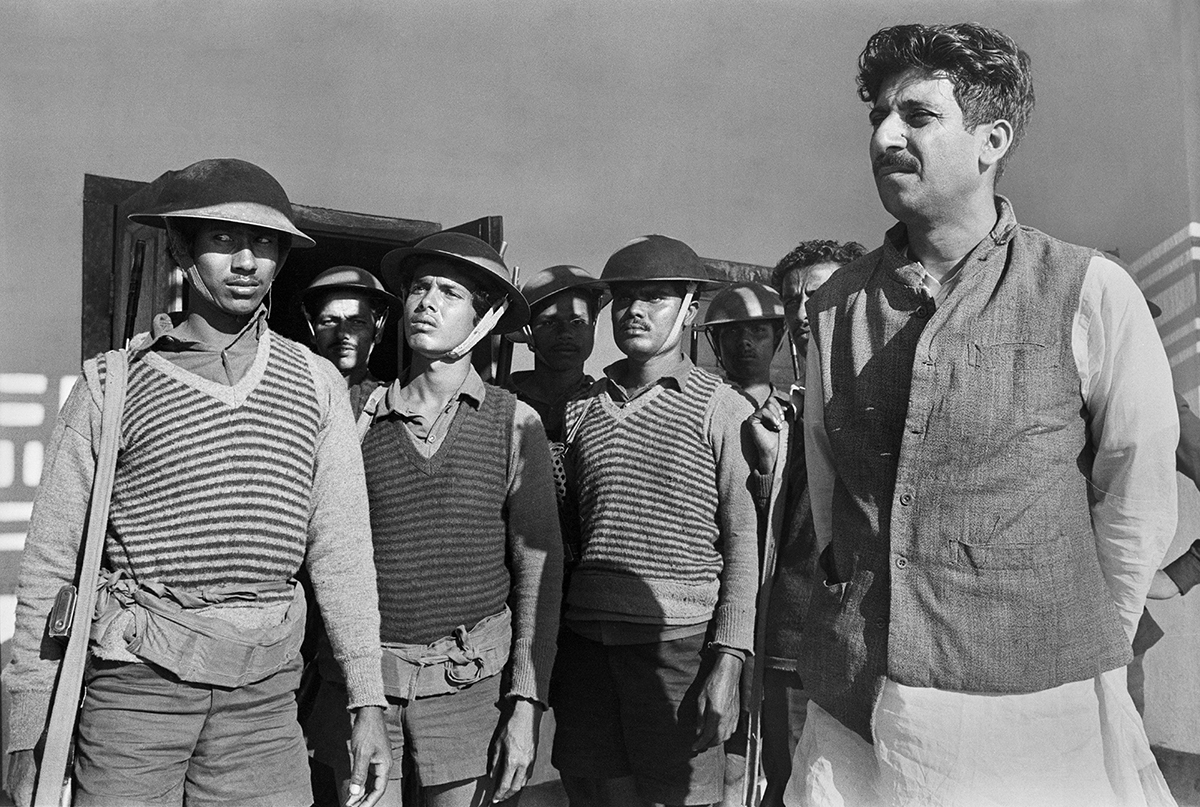

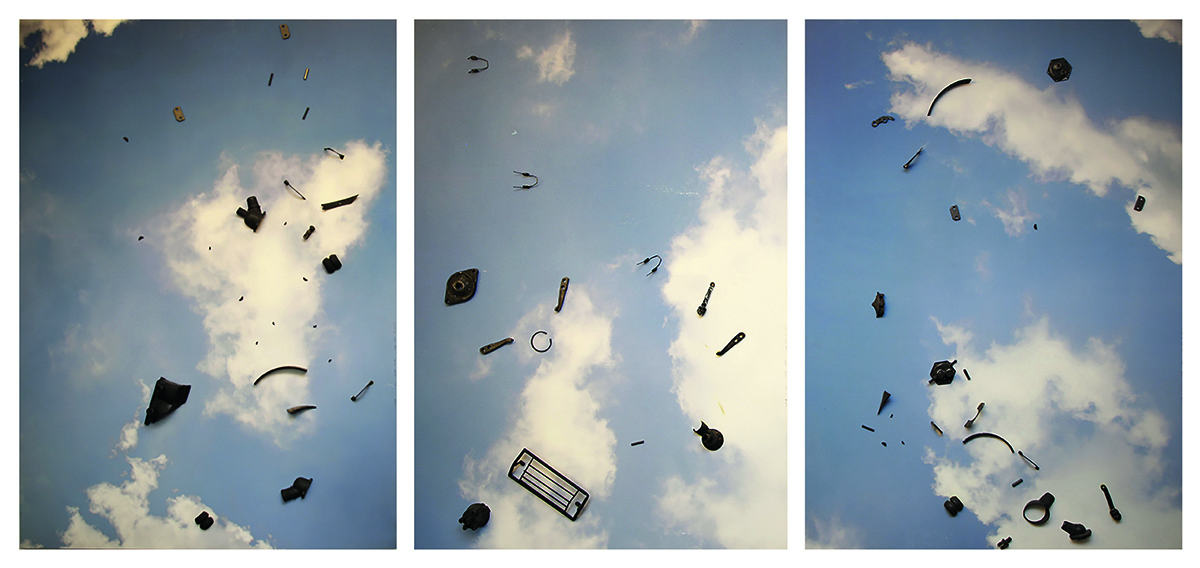

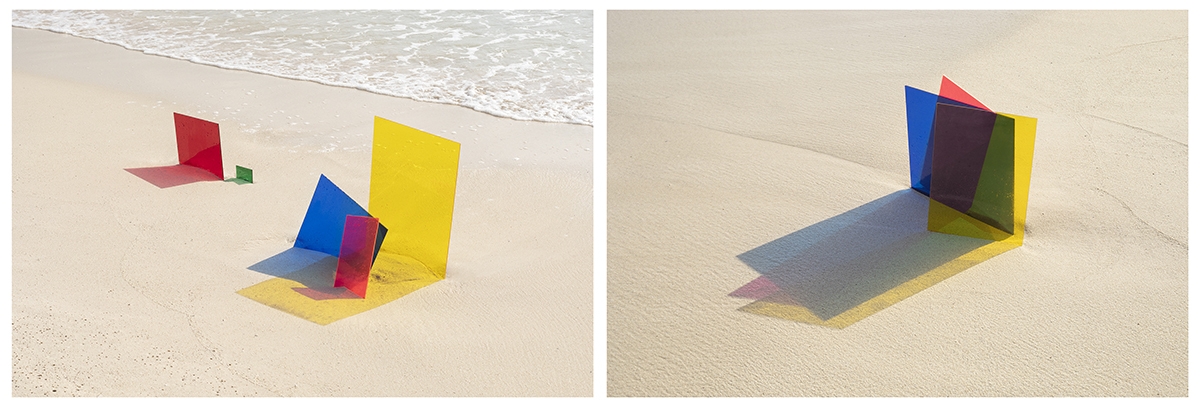

KAWS for Dior Homme SS19, 2018, Paris

LUX: When you started, consciously or not, you created work anyone can see. Now you also make works you can sell for private collections. Does it matter who sees the work?

KAWS: I don’t make work according to who I think might see it. If there’s a sculpture in a public setting, it will of course be different than a small canvas I paint. I want to make something that will engage a wider audience, so I’m conscious of creating things that are very inviting.

LUX: When you were a kid growing up in New Jersey, how did you start doing art?

KAWS: I think it’s always been a crutch for me. It was really since I was a child that I leaned into art, not just for communicating, but for having relations within school. I wasn’t really strong academically, I don’t think, and I saw art as a place I just went to. I loved that you could do it in a solitary kind of way, and bring it out into the world when you wanted. It just seems something like that could go on forever, until the end.

LUX: The art you created, even from an early age, was not traditional – it was your own original thing. Was that a conscious decision?

KAWS: When I was younger, I didn’t know a single person who was an artist for a living. It just seemed like something I did – similar to whatever sport might occupy a young person’s time. Obviously, I put a lot more energy into art-making than other things. I never imagined it could be something that you could make a living from. I didn’t have any examples of that as a child. So I thought it was something I would always be doing but I would have to find other ways to subsidise it.

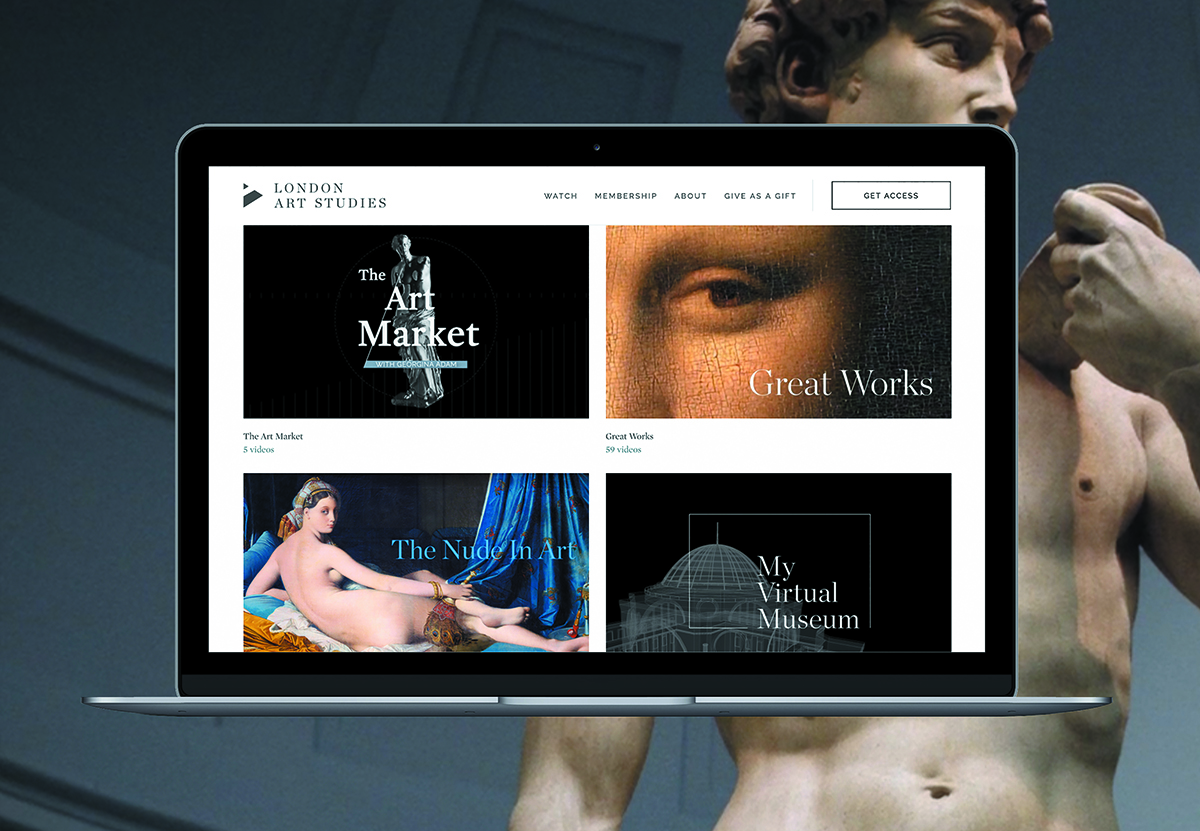

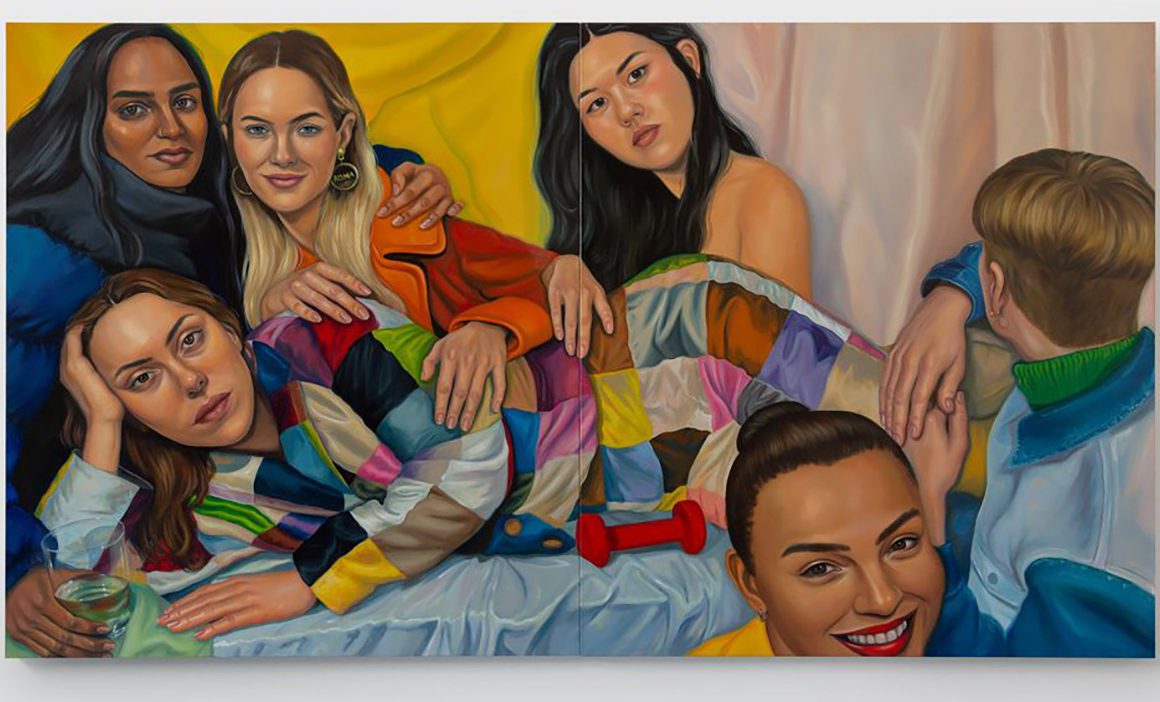

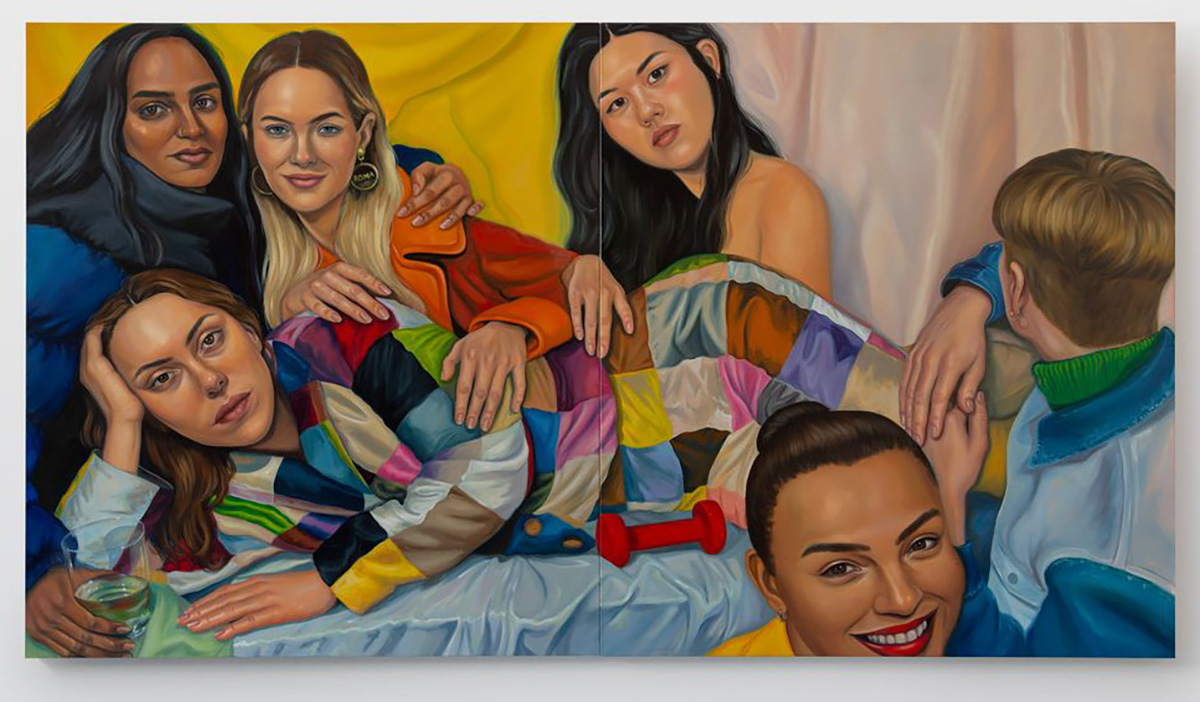

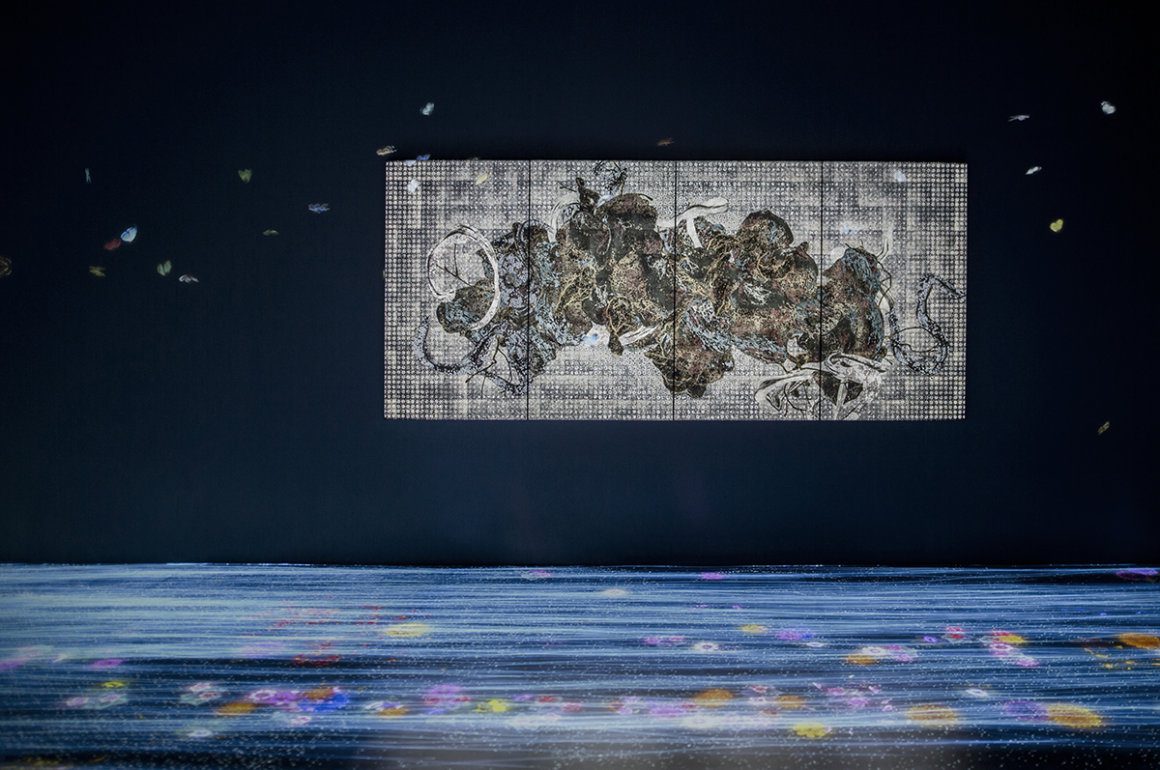

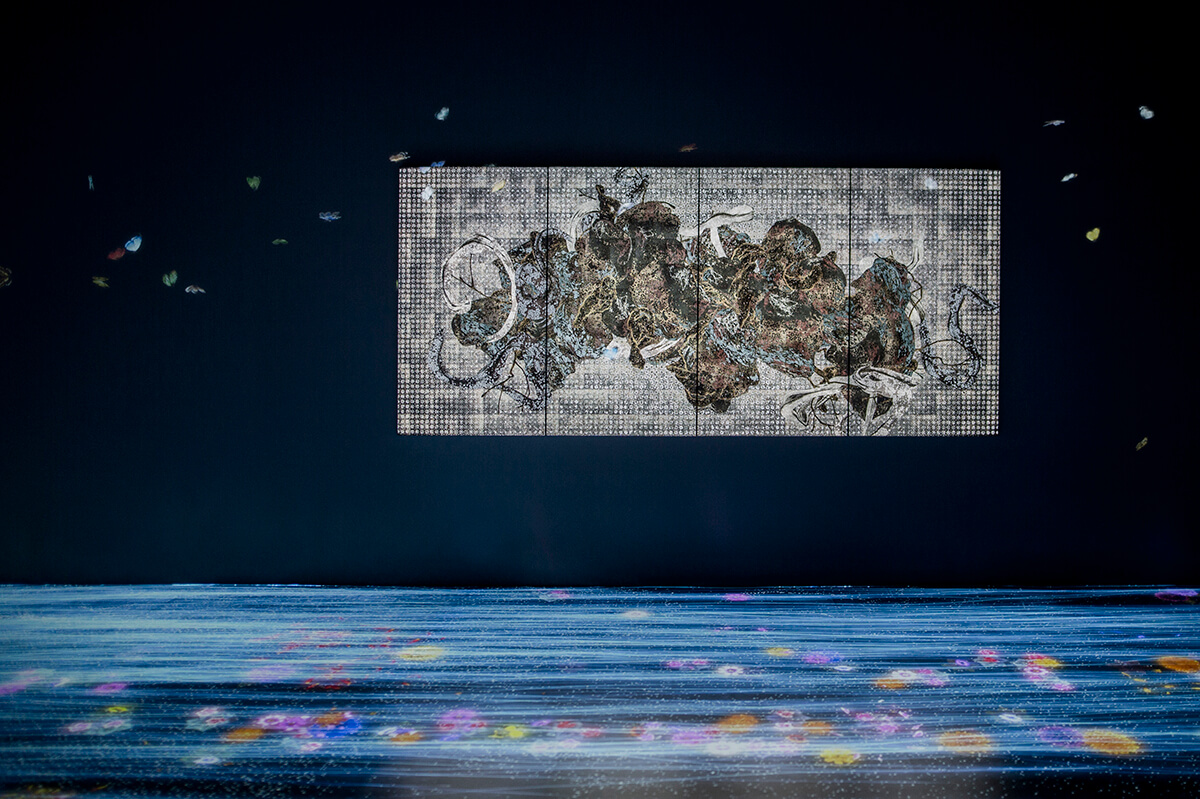

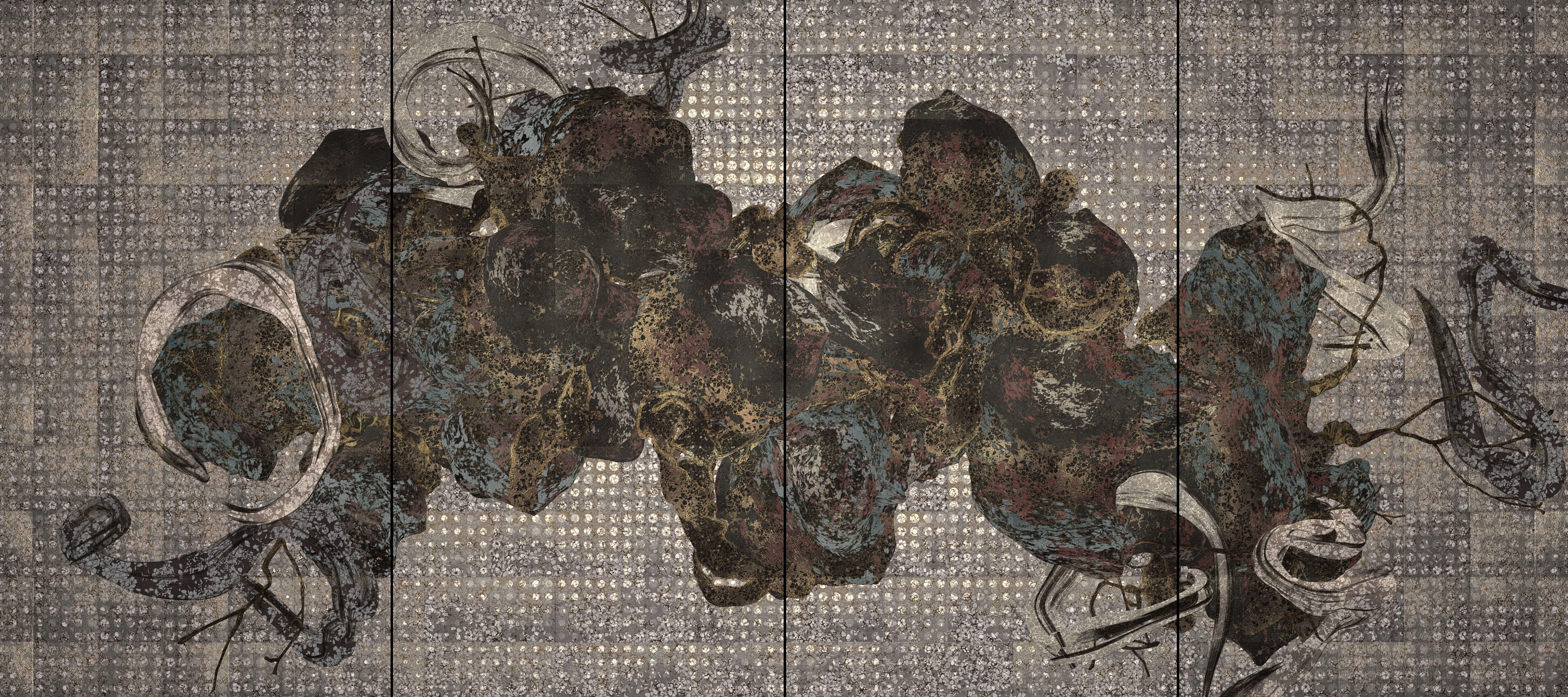

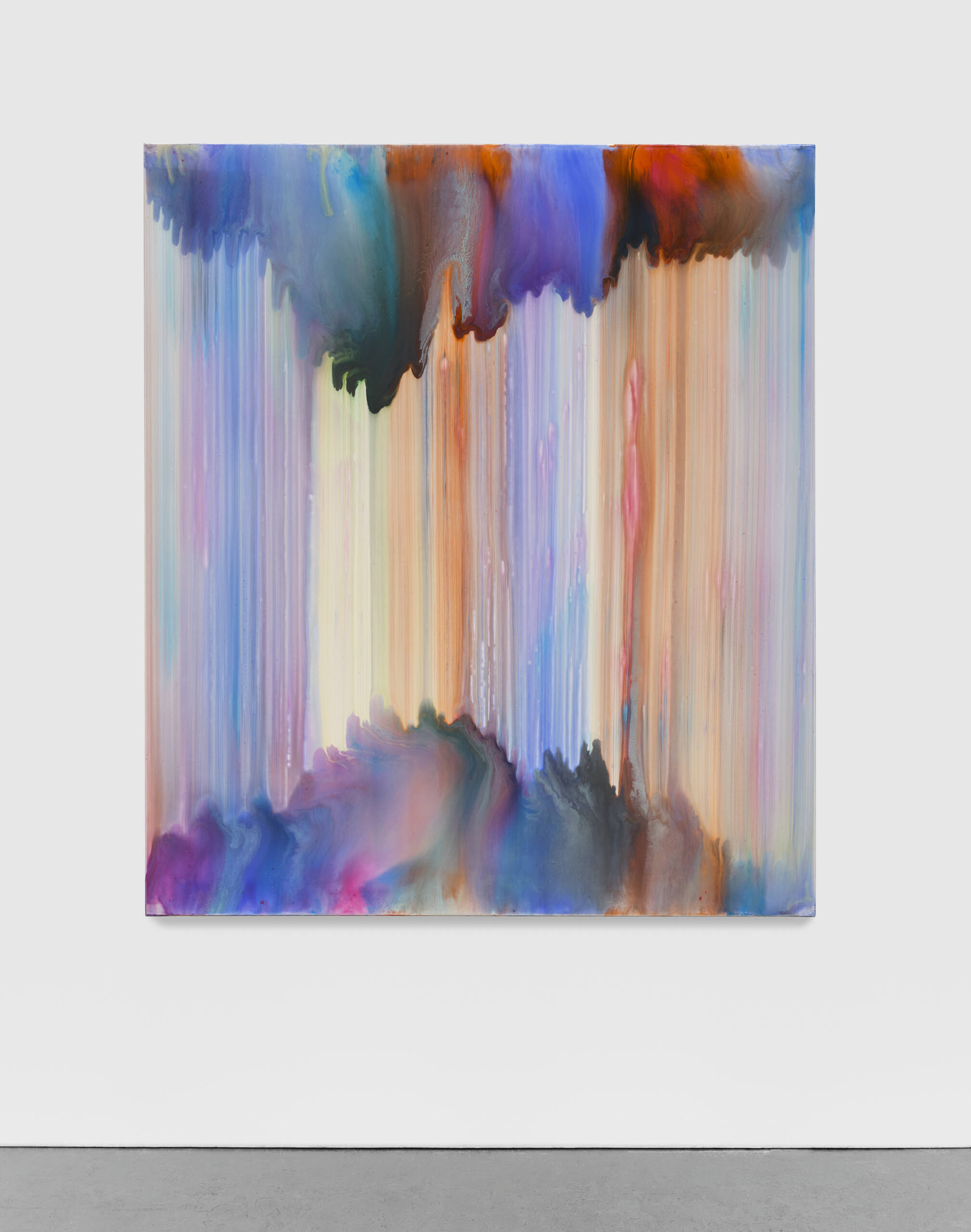

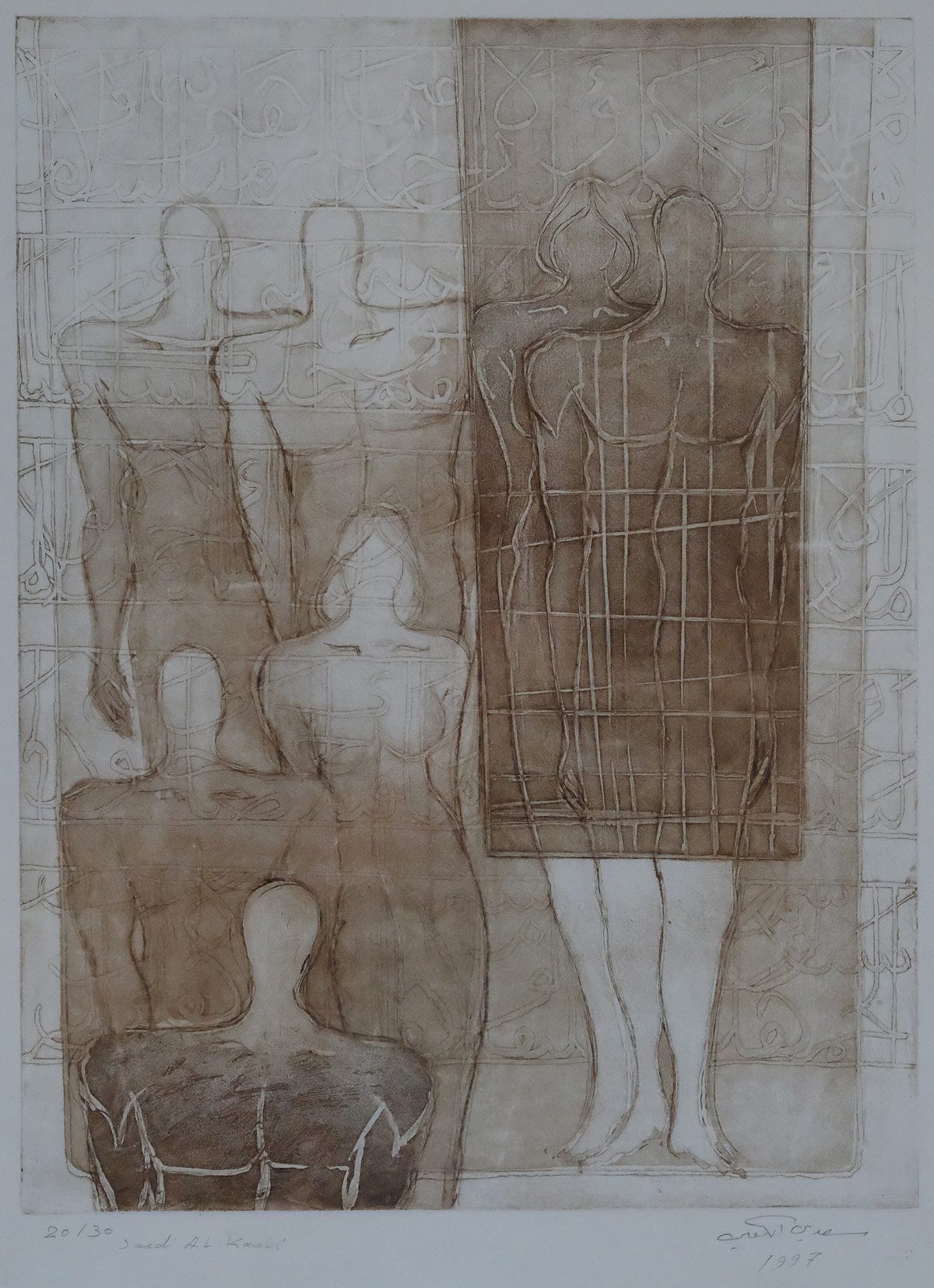

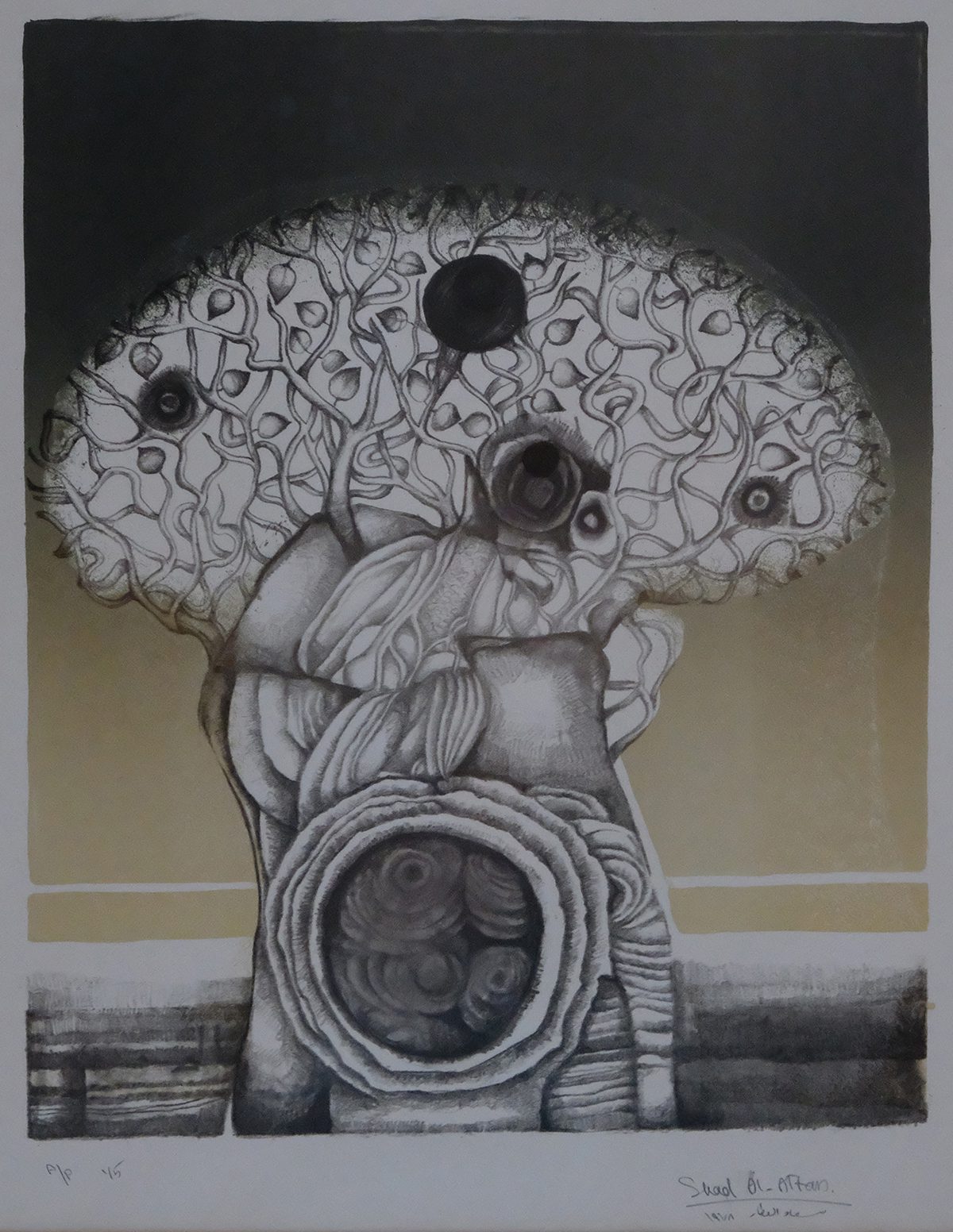

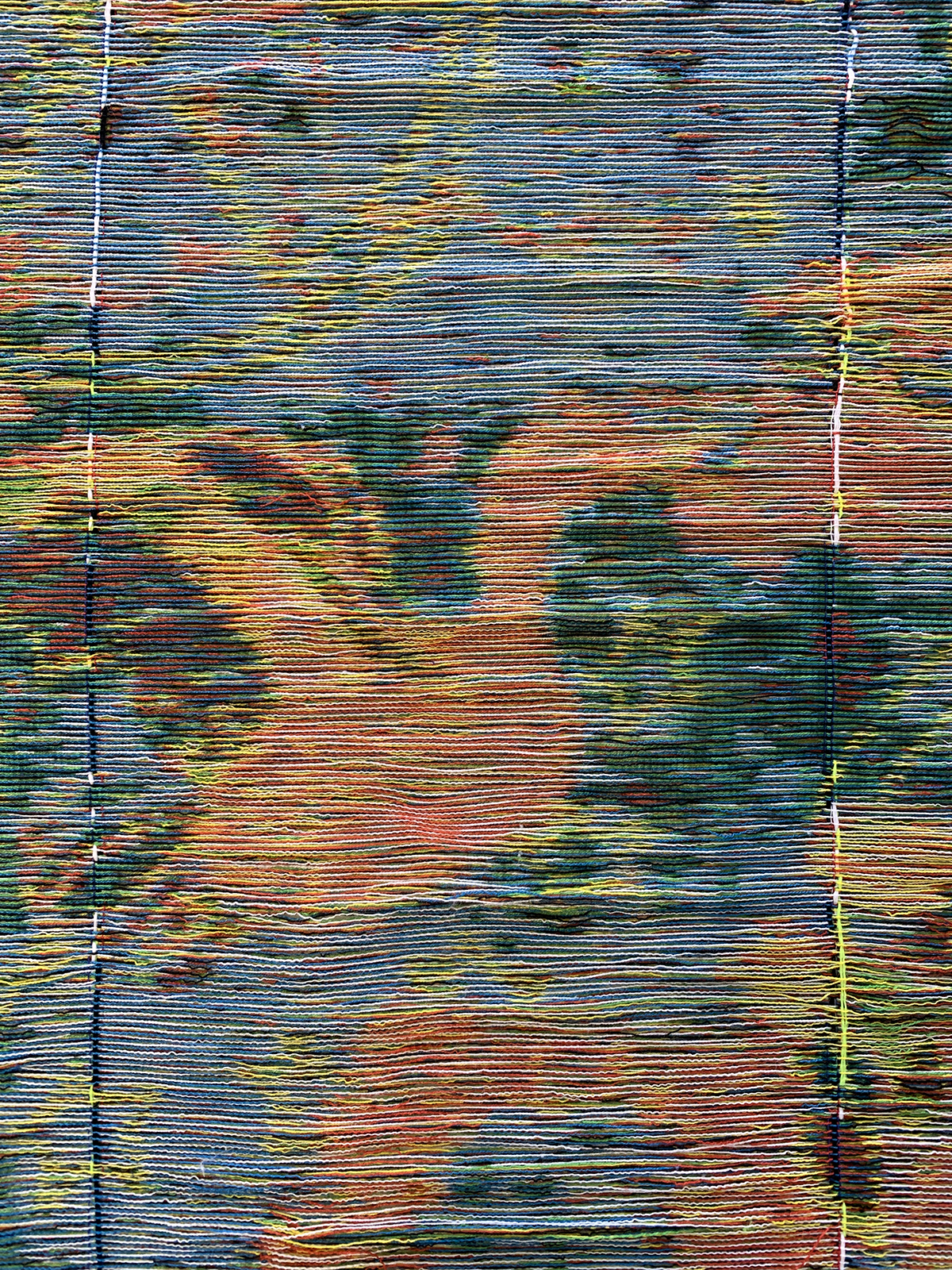

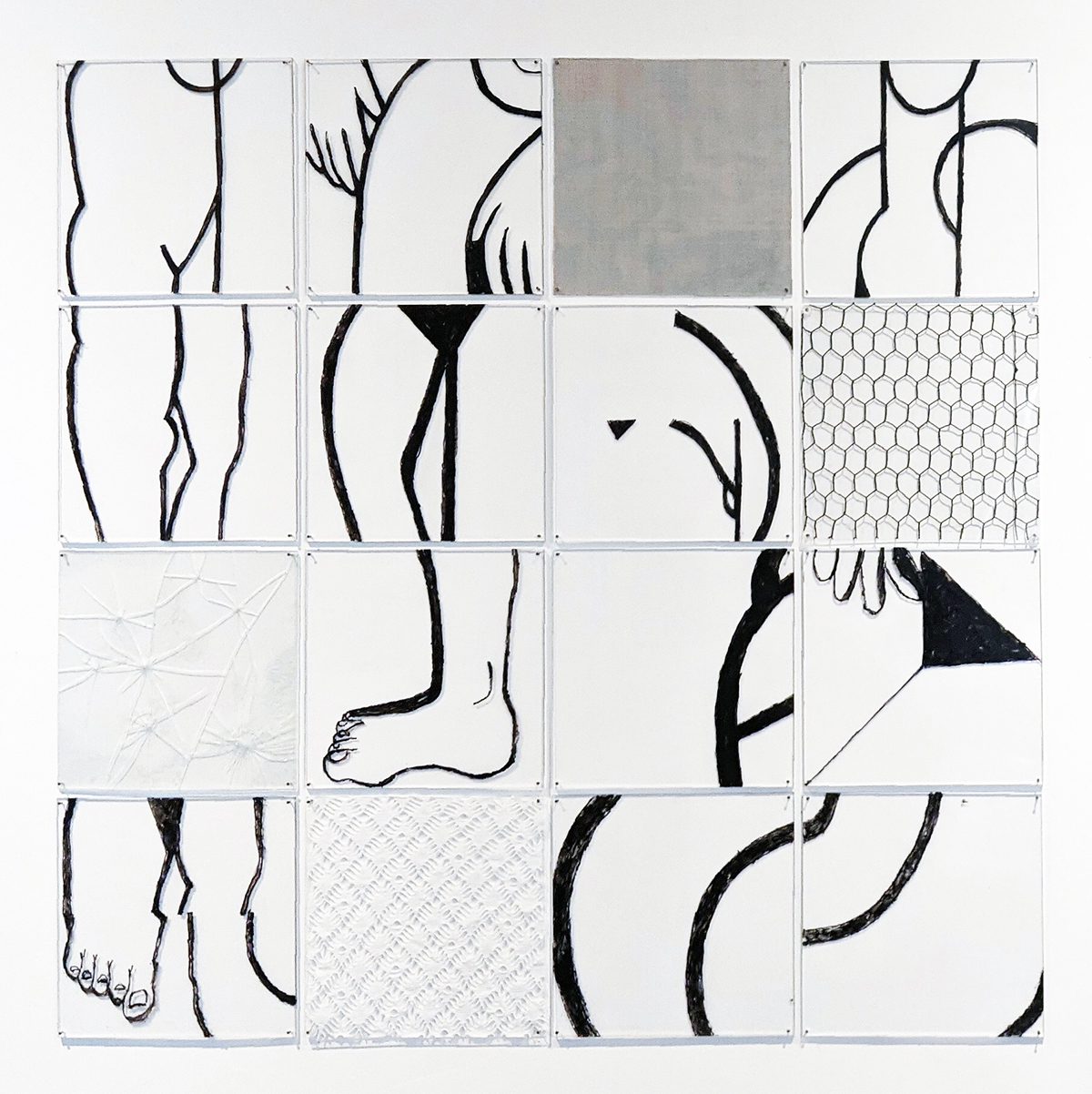

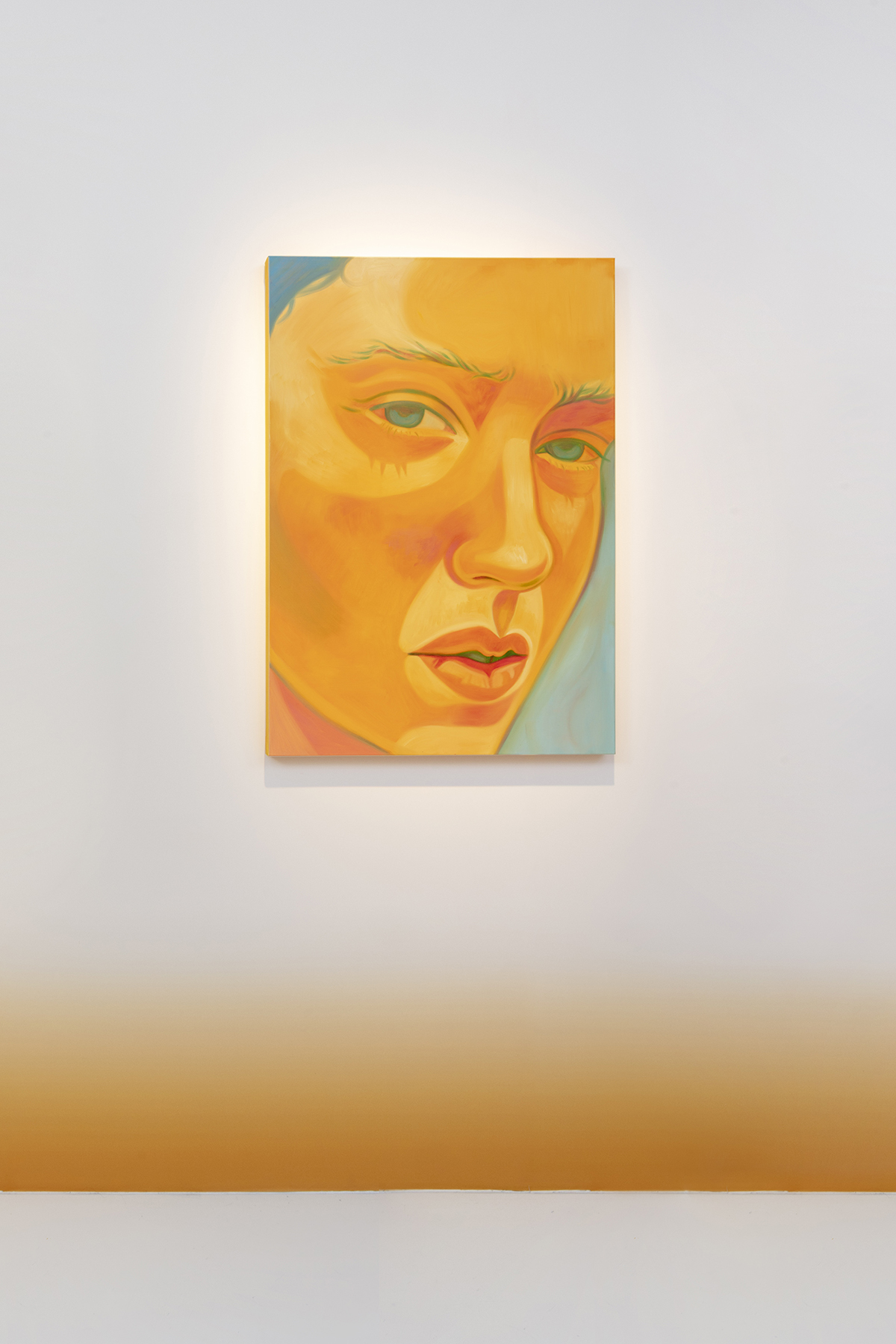

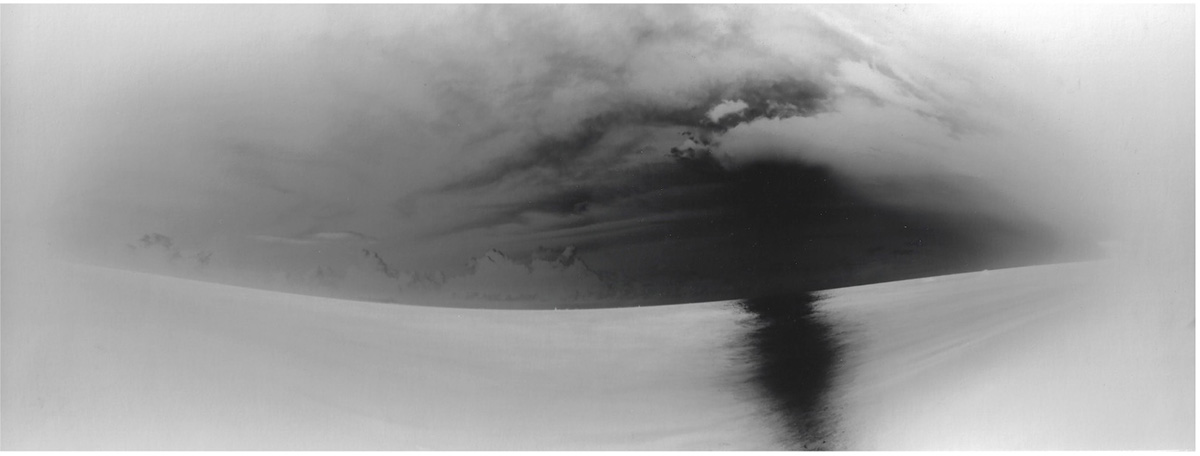

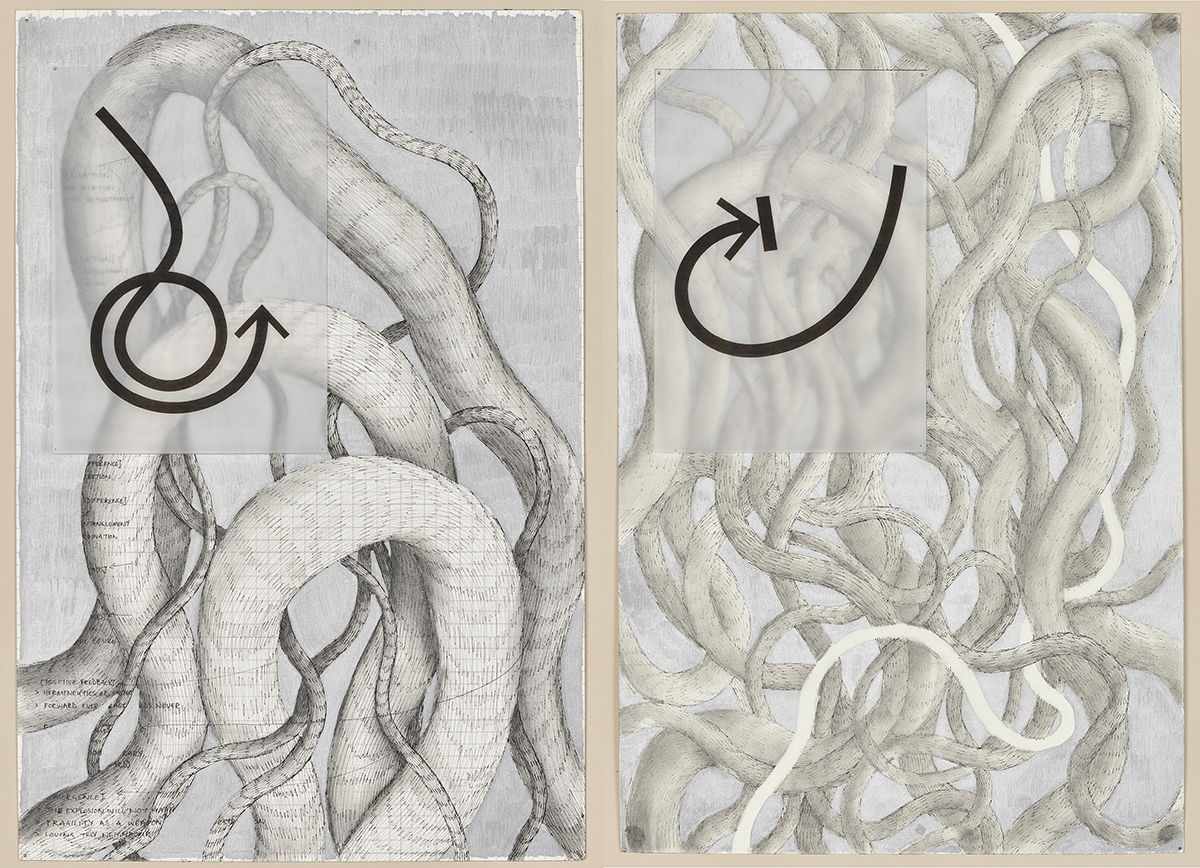

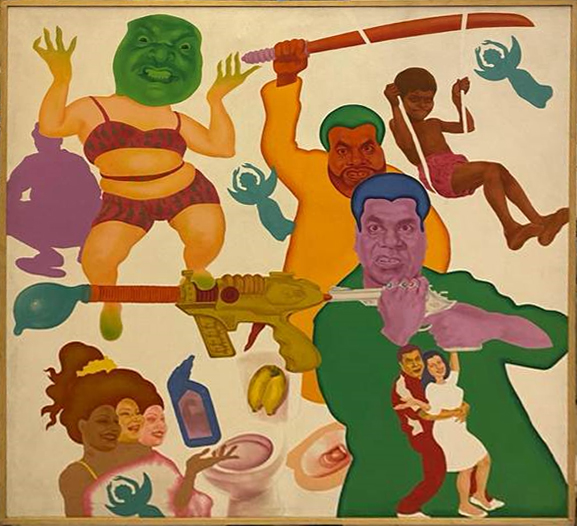

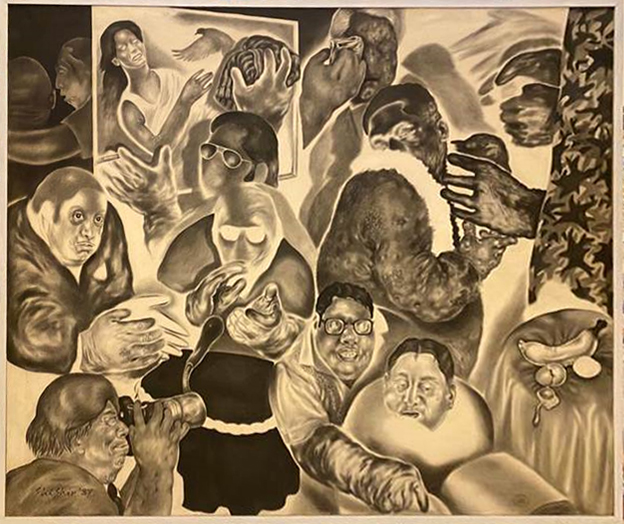

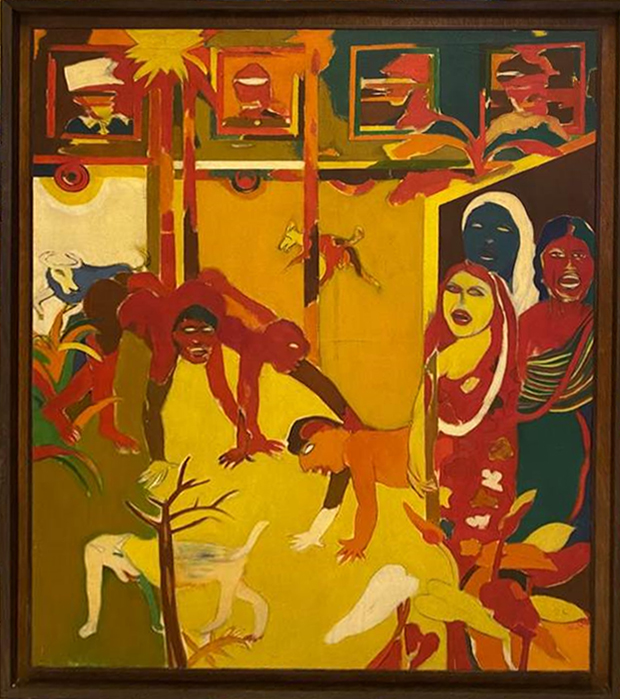

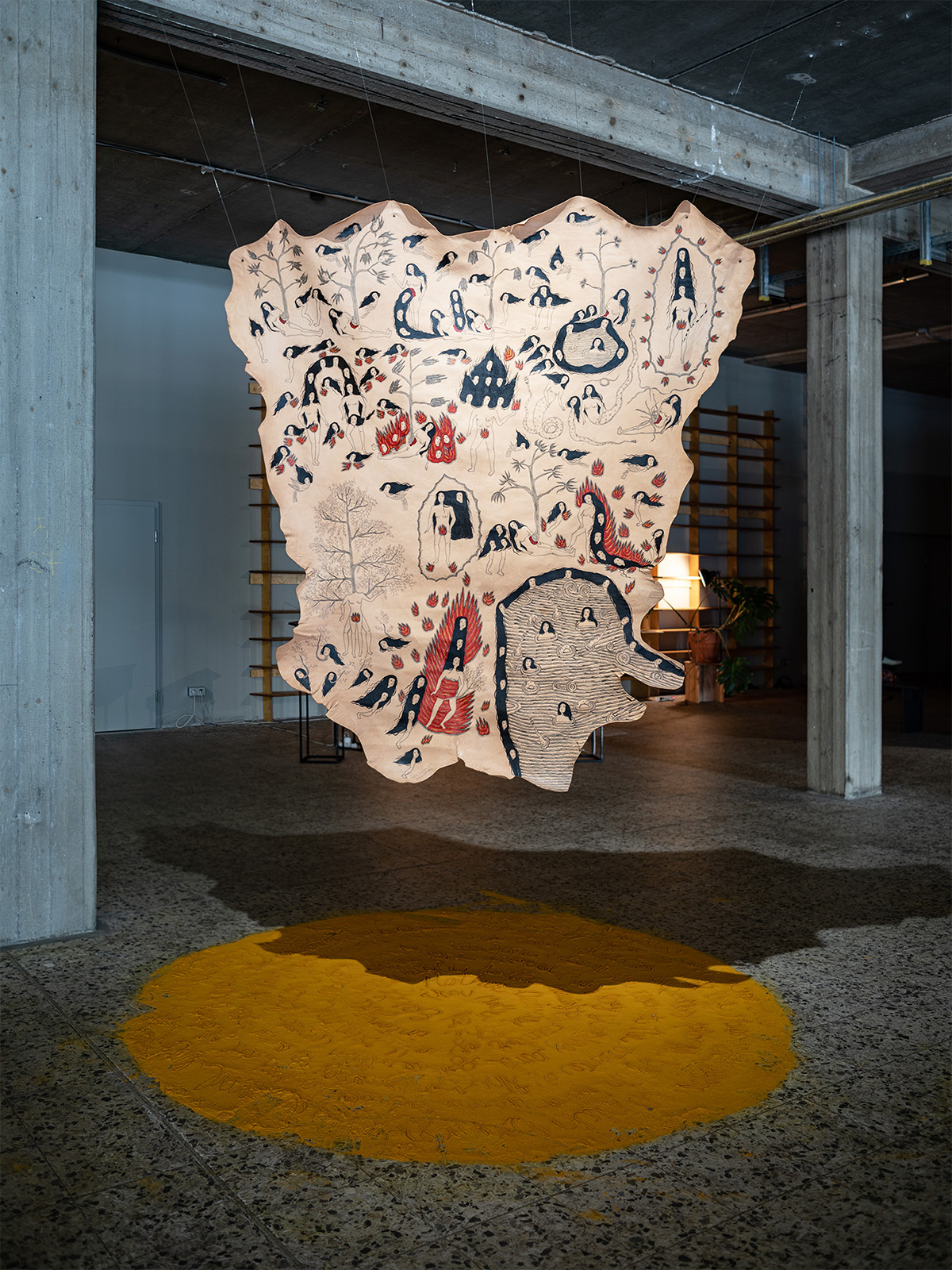

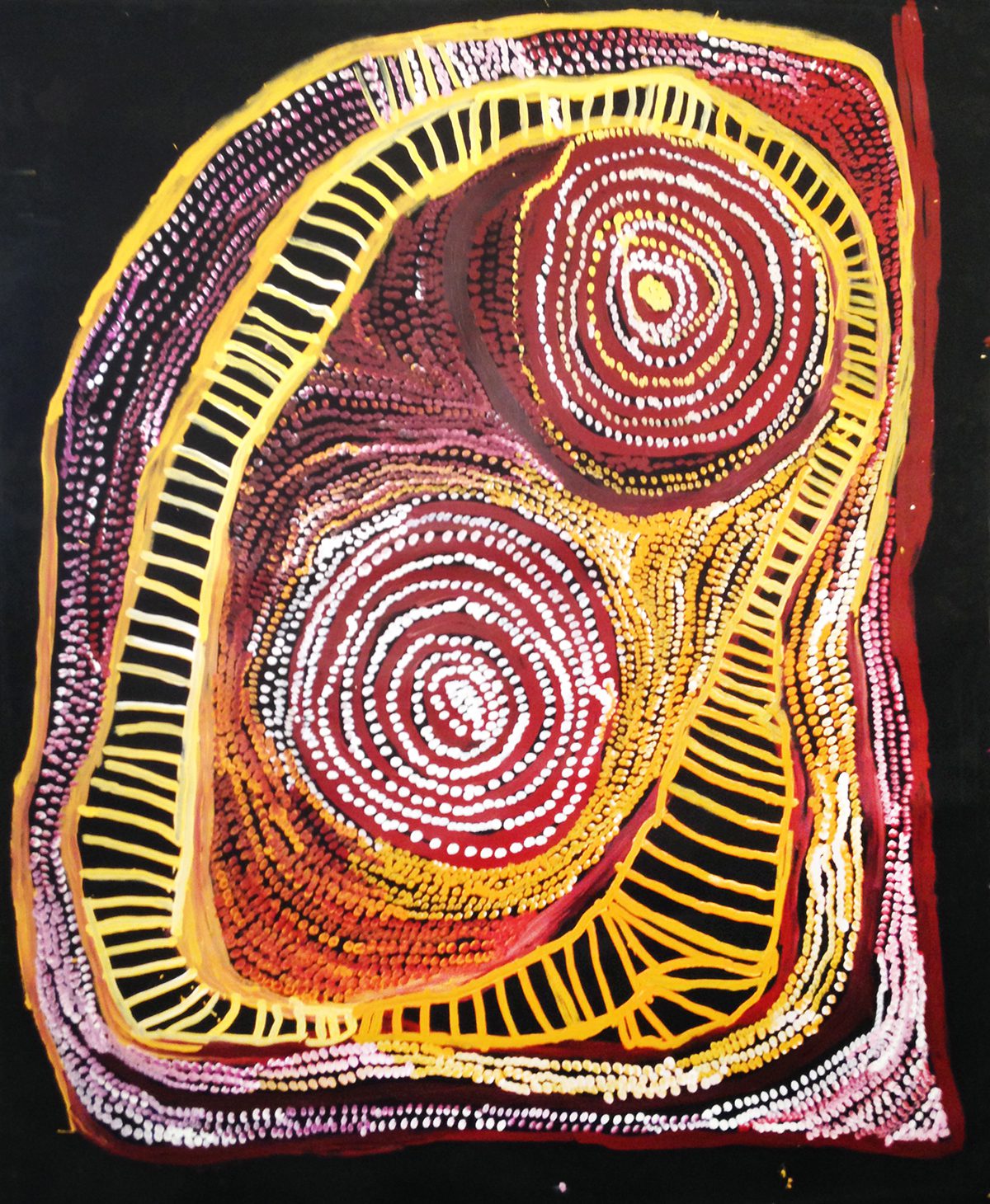

KAWS artworks at the light-filled studio

LUX: You’re at the confluence of art and luxury, streetwear brands and many other things. If someone came from Mars and asked what you do, would you just say you’re an artist?

KAWS: I would just say I’m an artist. I think that’s the simplest term. I think that communicates what I do. As far as working in different mediums, or different fields, I’ve always been open to exploring any of my interests. If I’m interested in streetwear or fashion or shoes, I dive in. There are so many interesting people doing interesting things, it would be a shame to limit myself from any opportunities to learn.

LUX: You must have noticed that the art world is a bit snobbish about artists working with brands: “It’s not real art, you’re selling out…”

KAWS: Definitely. Especially in the 90s. At first when I was younger, I thought, “Oh man, this is something I have to think about.” I soon learnt that the only thing I need to do is exactly what I want to do and let the chips fall where they may. When I opened my OriginalFake store in Japan in 2006, I said, “I really don’t care if I don’t show in galleries. This is something I want to do and if that’s a conflict so be it.”

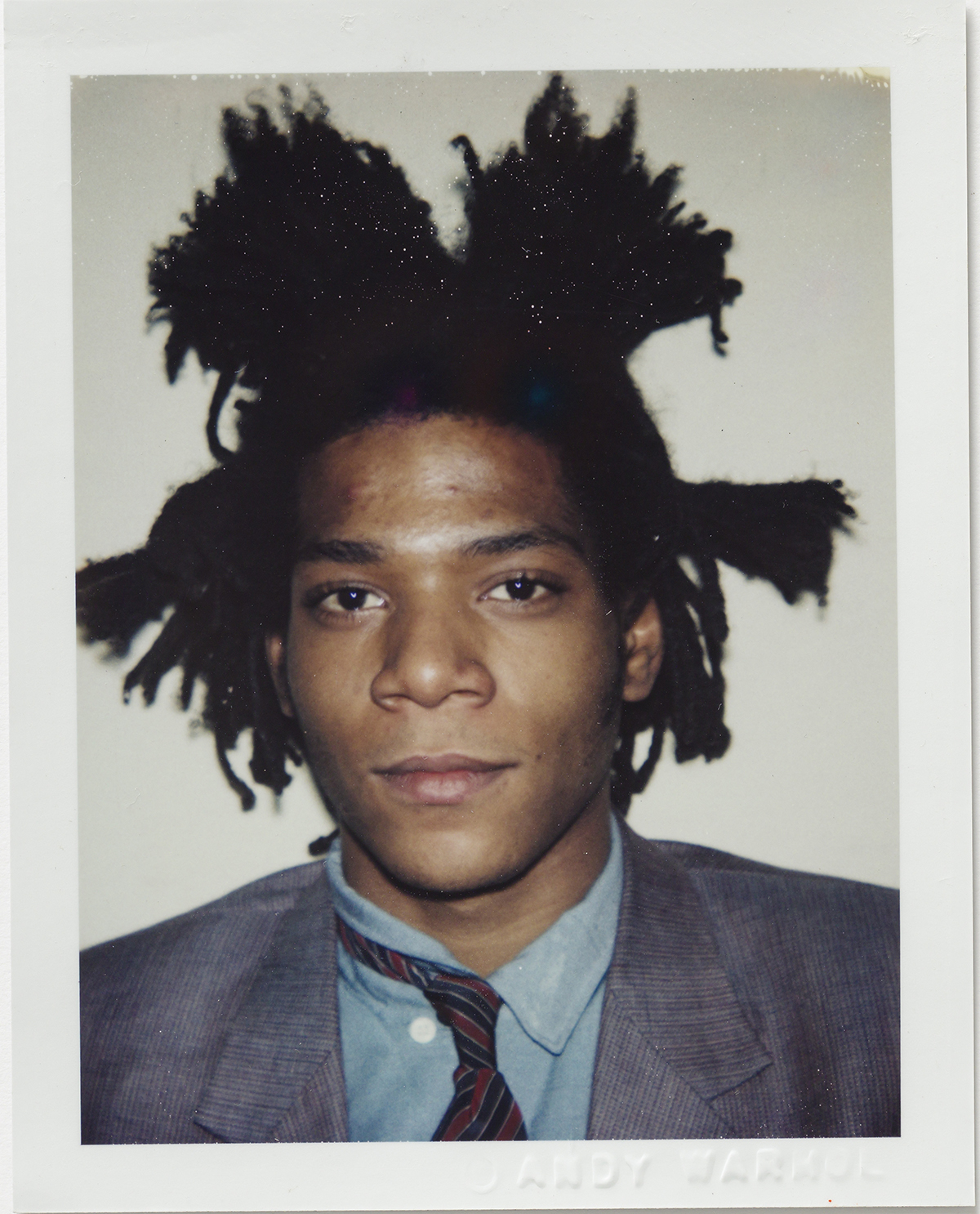

LUX: People have written that there’s a parallel with Andy Warhol, with a mix of ‘high art’ and commercial art, reflected in your works.

KAWS: Honestly, the more you learn about artists and history, the more you realise there are so many artists who delved into commercial opportunities and things that stimulated them creatively – Andy Warhol being a very large part of that. But you know there’s a lot more, it wasn’t just Warhol and Haring… Everyone kind of has their moments, whether they’re widely acknowledged or not.

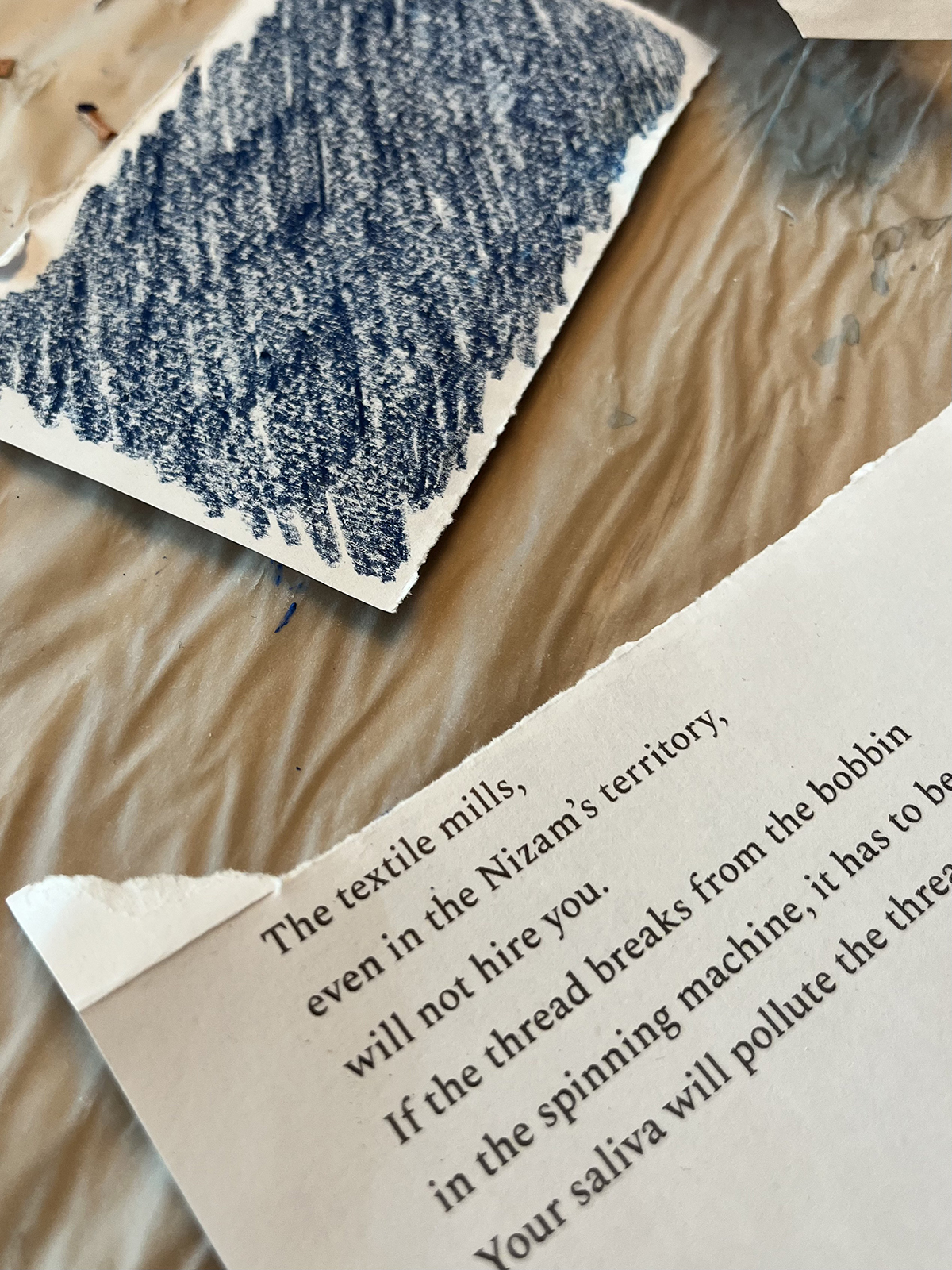

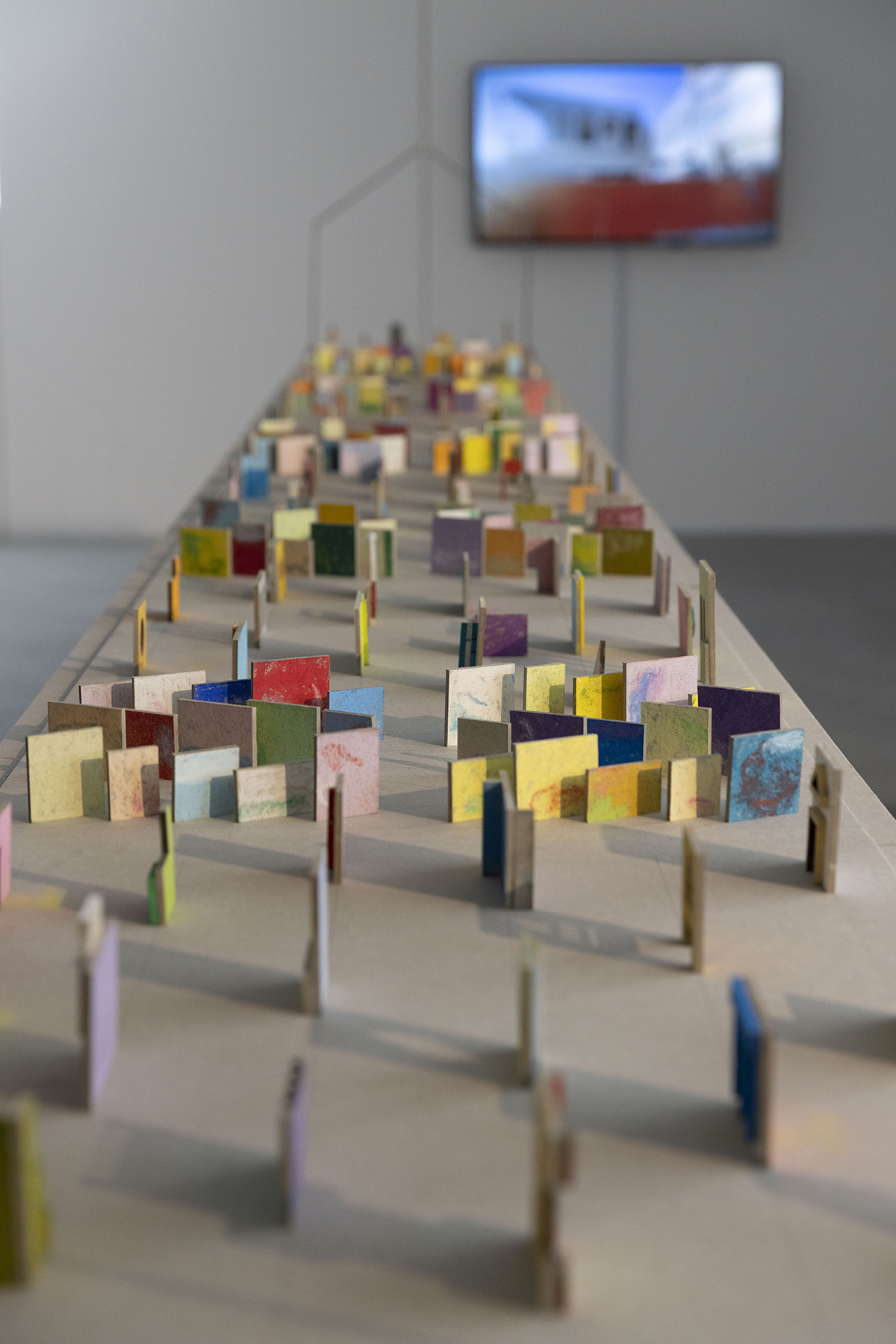

artwork and neatly arranged materials at the KAWS studio

LUX: Do you think that with a new wave of millennial art collectors, people are more accepting that you can do brand collaborations as well as sell artworks through galleries?

KAWS: I think it’s become a lot more natural. Kids who grew up in my generation and younger, this is a language they’re familiar with. This was a big part of why I loved Japan so early on; it felt like there was a focus on making good stuff no matter the “category” it fell under, and that was the only real structure to it – if you’re going to do it, do it well. A sort of openness between design, art, furniture and fashion. I think the generation coming up now have grown up on this and many don’t give it a second thought. The world has become a smaller place, because of social media and the internet and whatnot. From your house, you can definitely have a view of what’s going on globally and I think that a lot of the barriers that were existing in the 90s have been broken through. Things shift, so it could turn back in the other direction, but I can’t imagine that.

LUX: It sounds like you wouldn’t be too bothered, if things shifted, as long as you were doing what you were doing?

KAWS: My goal as an artist is to bring the things in my mind to fruition. If I can find ways of doing that, then I feel like it’s successful.

LUX: Were collaborations and creations in design and fashion something that you started doing back when you were very young?

KAWS: I grew up skating and really loving that graphic culture: skateboards, T-shirts and stickers and everything that comes with it. When I’m making work, I always think about what reached me when I was young. What got me on this path? What did I enjoy? I try to make work that is true to that feeling and can reach people in those ways. It’s this sort of casual channel that introduced me to art and got me interested in the first place.

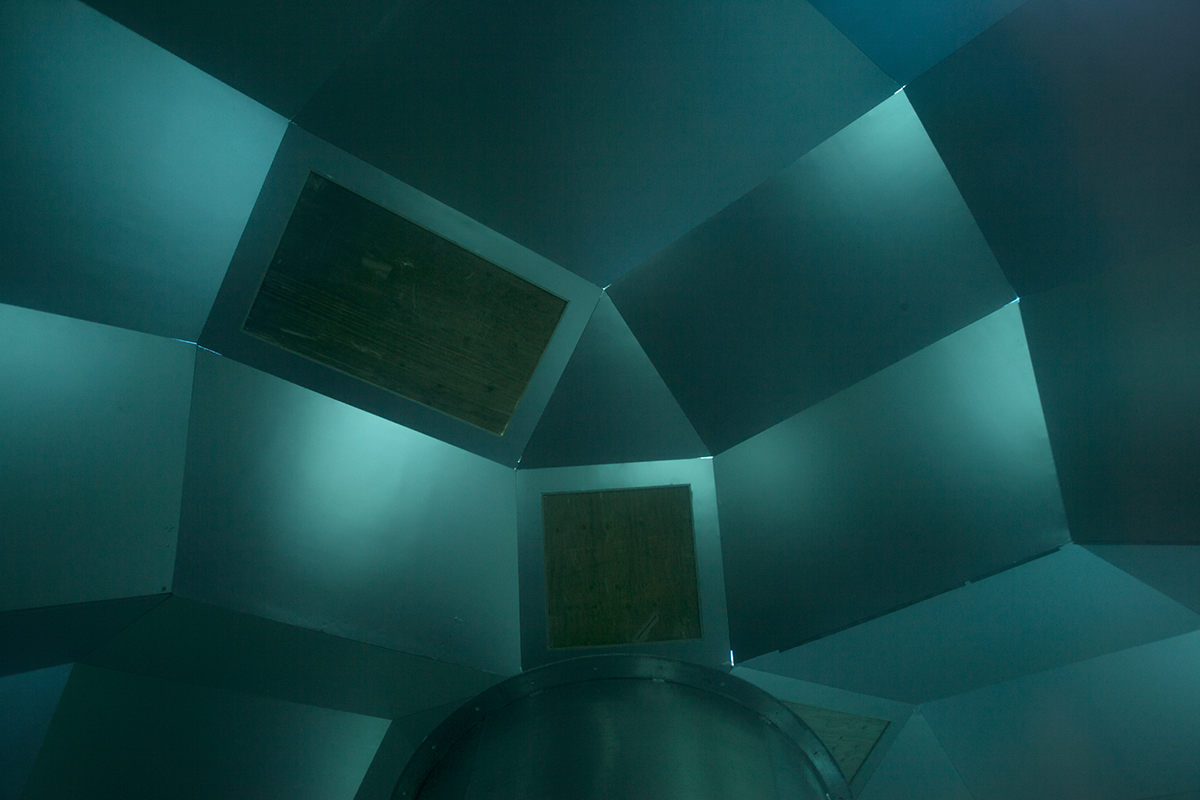

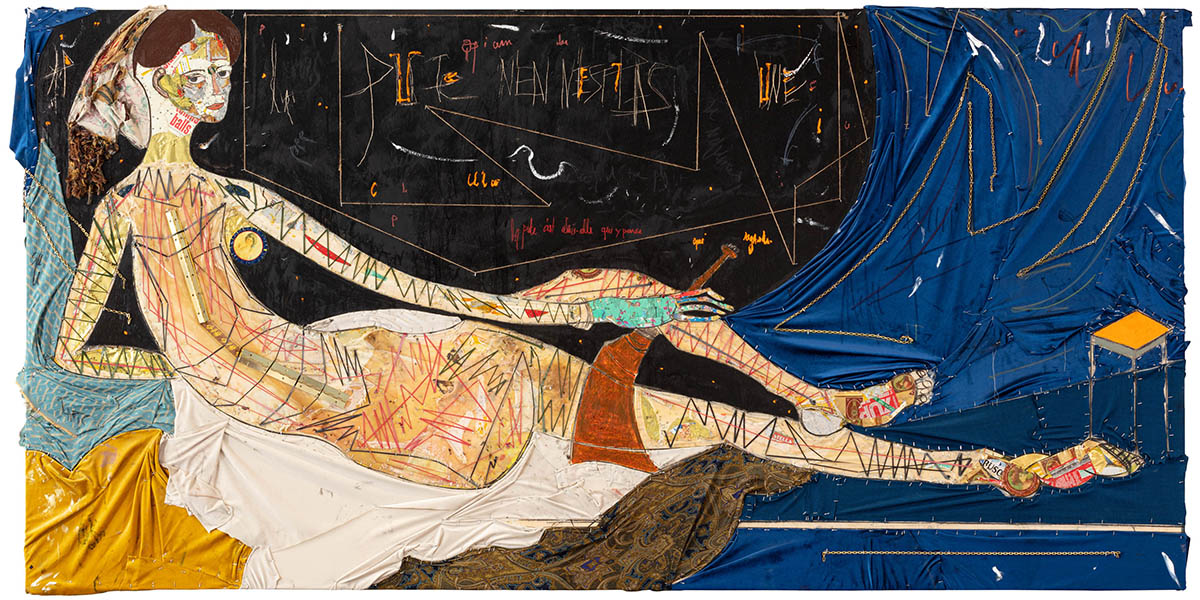

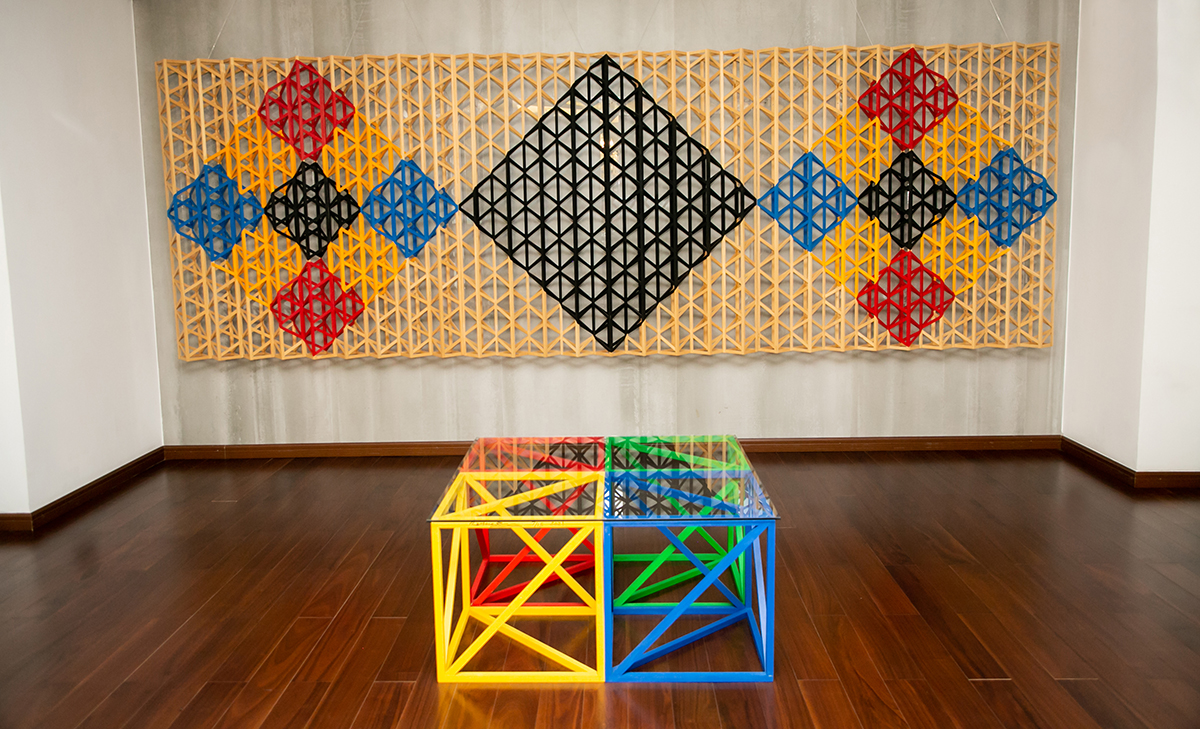

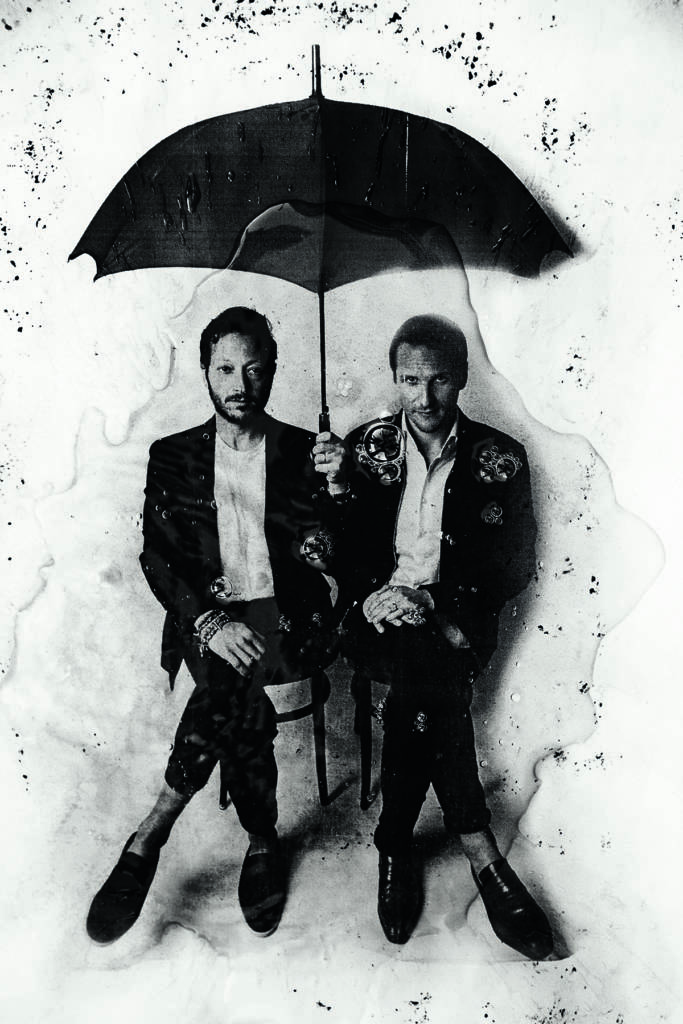

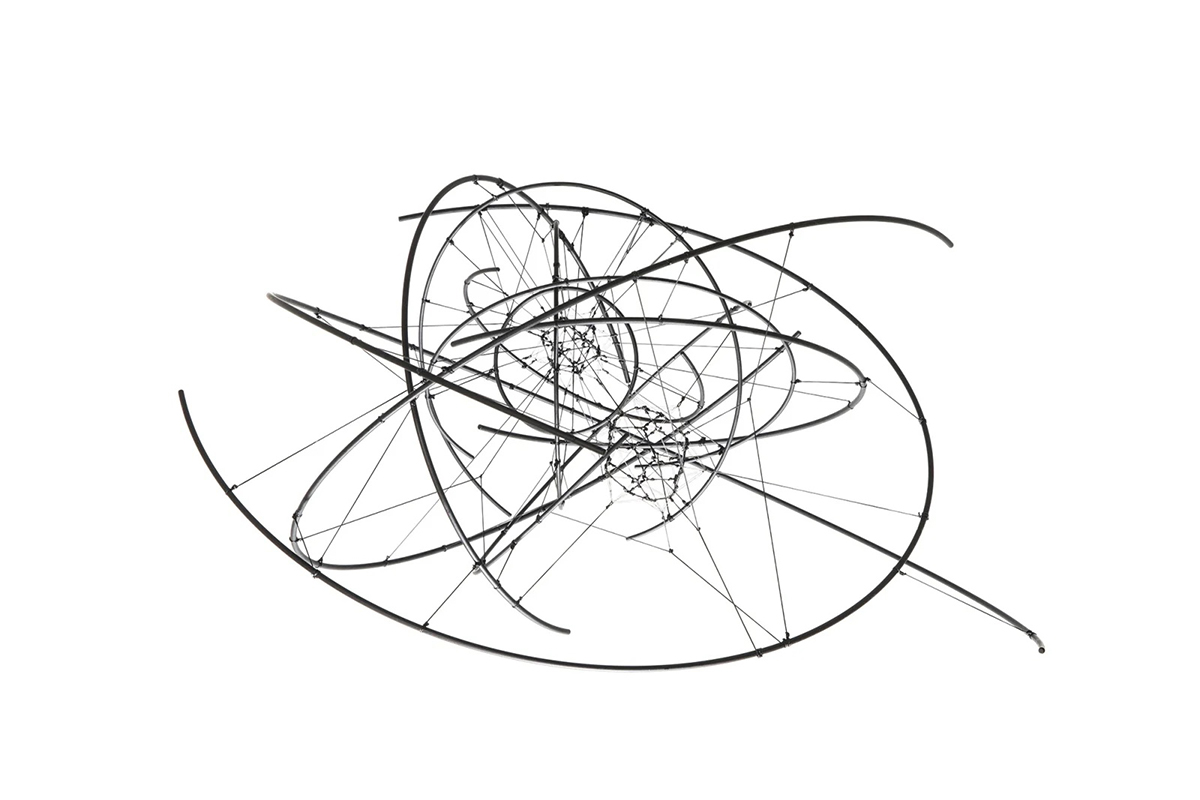

COMPANION (PASSING THROUGH), 2010, by KAWS;

LUX: There’s such an array of mediums that you work in. How do you know what you want to use, whether VR, a sculpture, work on paper? How do you make up your mind?

KAWS: I’m not methodical in any way. It just depends on what my interests are at the moment,

and what opportunities I see available for the medium I’m working in. So I might get heavily into VR, and then turn back to painting and drawing. If sculpture is on my mind, I may put that mask on and get into that work. A lot of the stuff I do happens organically, especially with collaborative work or working with musicians.

LUX: You’ve talked about what your work communicates to people. But you haven’t told me about what you would like to communicate.

KAWS: I don’t tell people what they need to see when they’re looking at the work. I think that would be impossible. They all approach it through their own lens, and have their own experience to add. I make work for myself, and the way it’s interpreted by someone else is out of my grasp.

LUX: Is there something therapeutic about making your work?

KAWS: Yes, making work is completely therapeutic to me. It’s sort of the way I navigate life. I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I wasn’t making work.

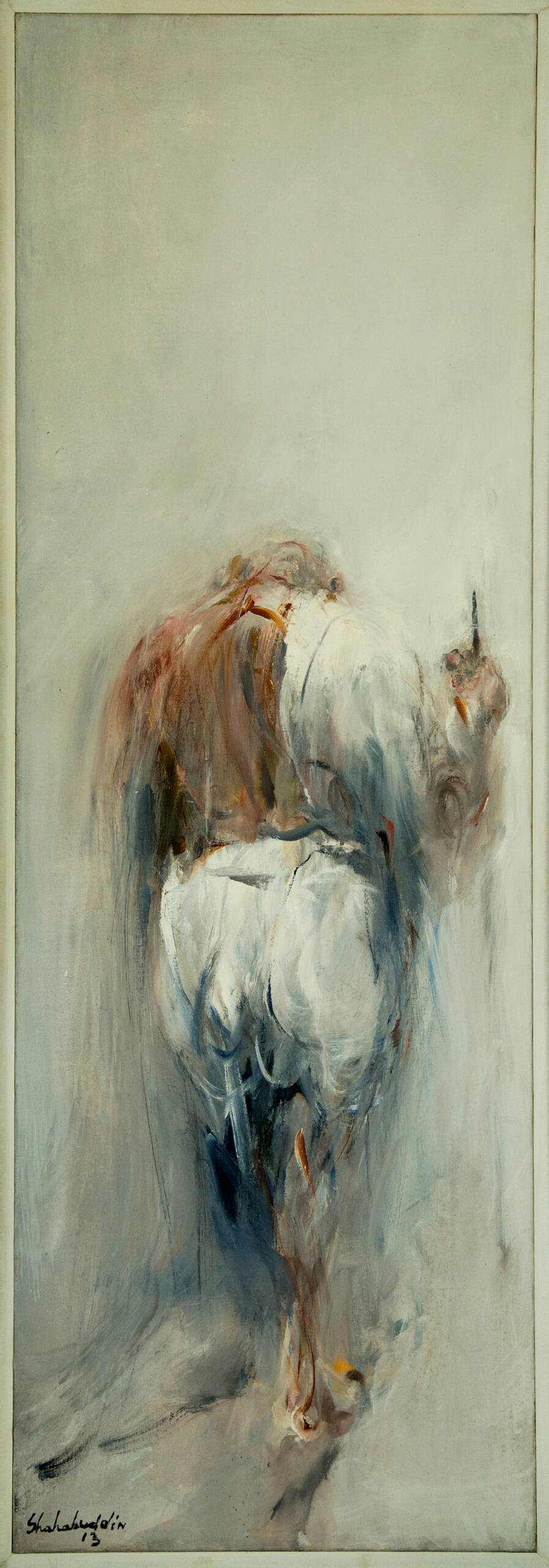

the artist, art and materials at the studio;

LUX: What would you say to a young person who wants to become an artist but doesn’t know how?

KAWS: I don’t think any artist knows how to become an artist when they’re younger. It’s just something you’re driven toward or not. If you’re going to be an artist, I don’t think it’s a choice; you realise it’s what you have to do.

LUX: Has anything changed?

KAWS: It’s a long path in being an artist and the interesting part is how you form this body of work over a long period of time. How do you change as a person, how do you bring that work into play with your new thoughts? I don’t grow tired of it. I’m taking a visual language and moulding it over time. I think this little process is great.

LUX: Is it very different working with a Nike than with a Dior?

KAWS: No, it’s just different people, it’s just case by case. It really depends on the project and the people. Similarly, larger companies can be just as easy if not easier than a little boutique collaboration. Dior was really simple because I was working with Kim Jones, and he and I are pretty friendly. It was fun. It was just us asking how we can do this and we did it all under an intense timeline.

Read more: A tasting of Bond, California’s new luxury wine

LUX: Is there anyone still looking down at an artist who does cereal boxes as well as high art?

KAWS: Of course, I’m sure there are probably tons of people who look down on it. The world is full of opinions and you really can’t worry about it or you’ll just sit on your hands and make nothing. If you were to weigh in the opinions of every stranger, what would you get done? The cereal project was a blast. I want to do more of that. I love knowing that you can walk into a convenience store, on the corner of your block, which you’ve walked into every day of your life, and suddenly, my work’s in there and you can buy it for a few dollars. That’s priceless to me. I understand, a lot of people get to see stuff online, but most people never get to a gallery or museum, and the thought of them owning it is beyond them. Doing projects like that puts you in contact with people in a very candid way. When I’m working on something like that, I’m thinking it’s no different to a print edition, or anything else.

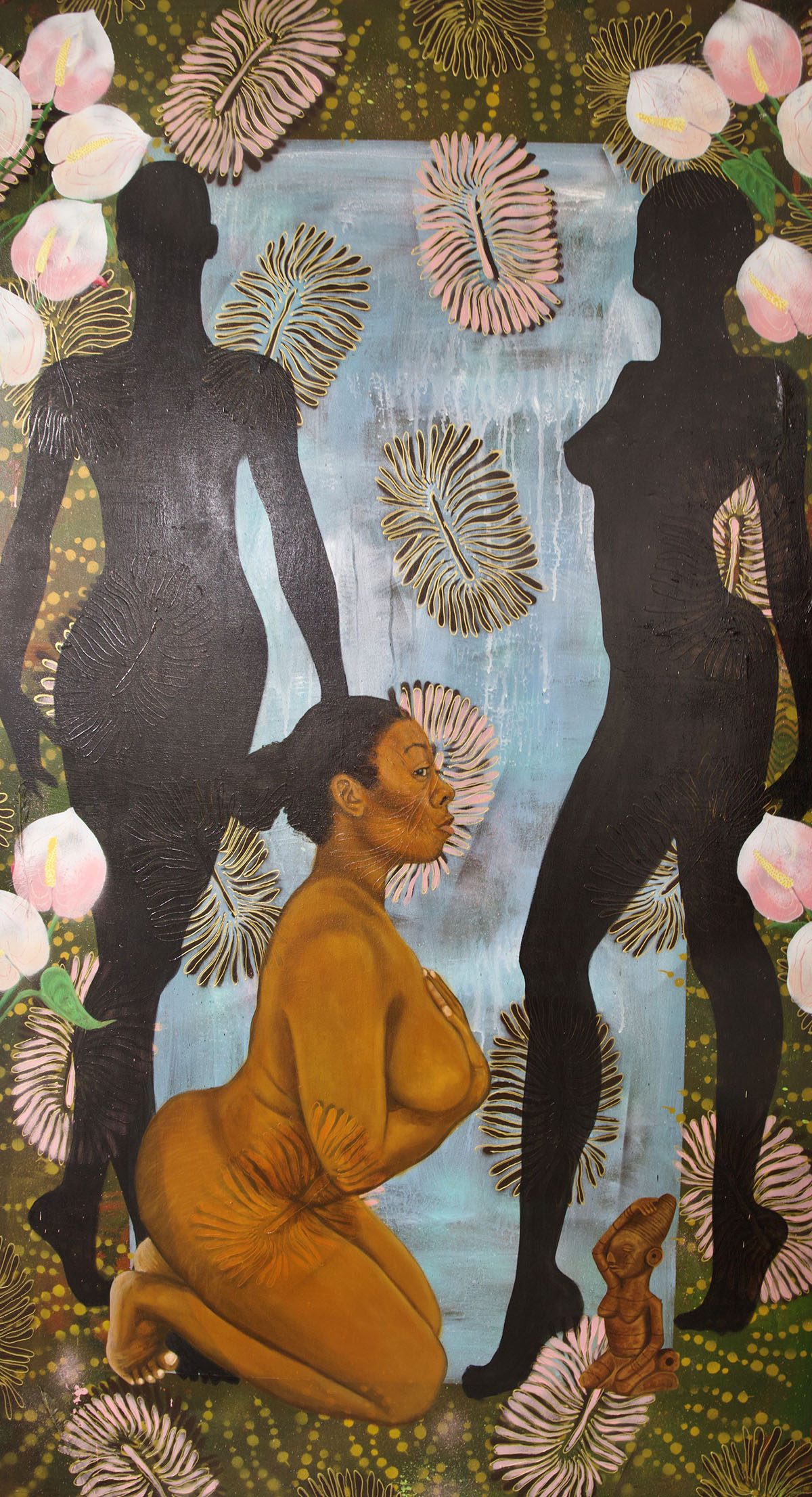

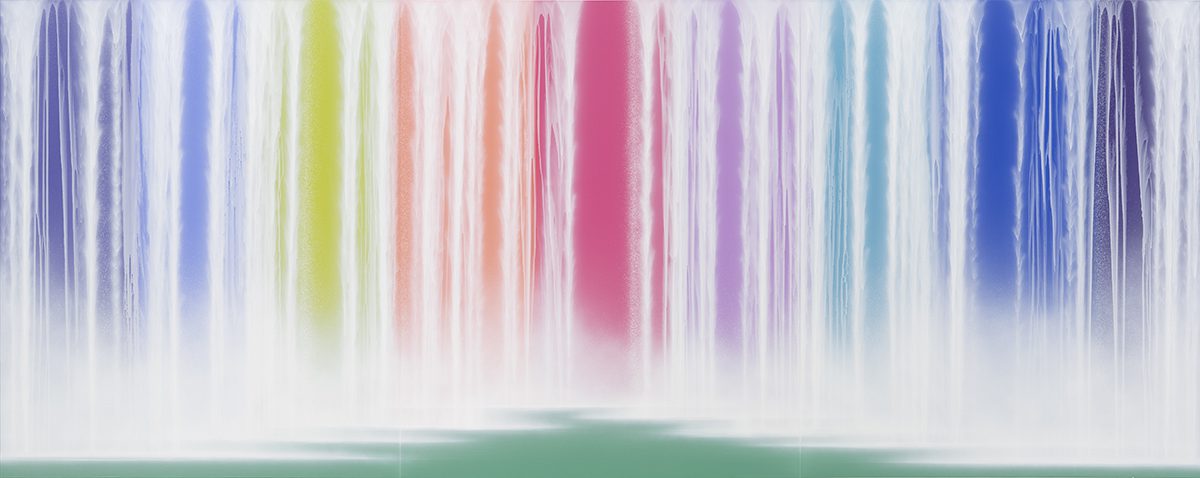

KAWS (HOLIDAY), 2022, by KAWS, China

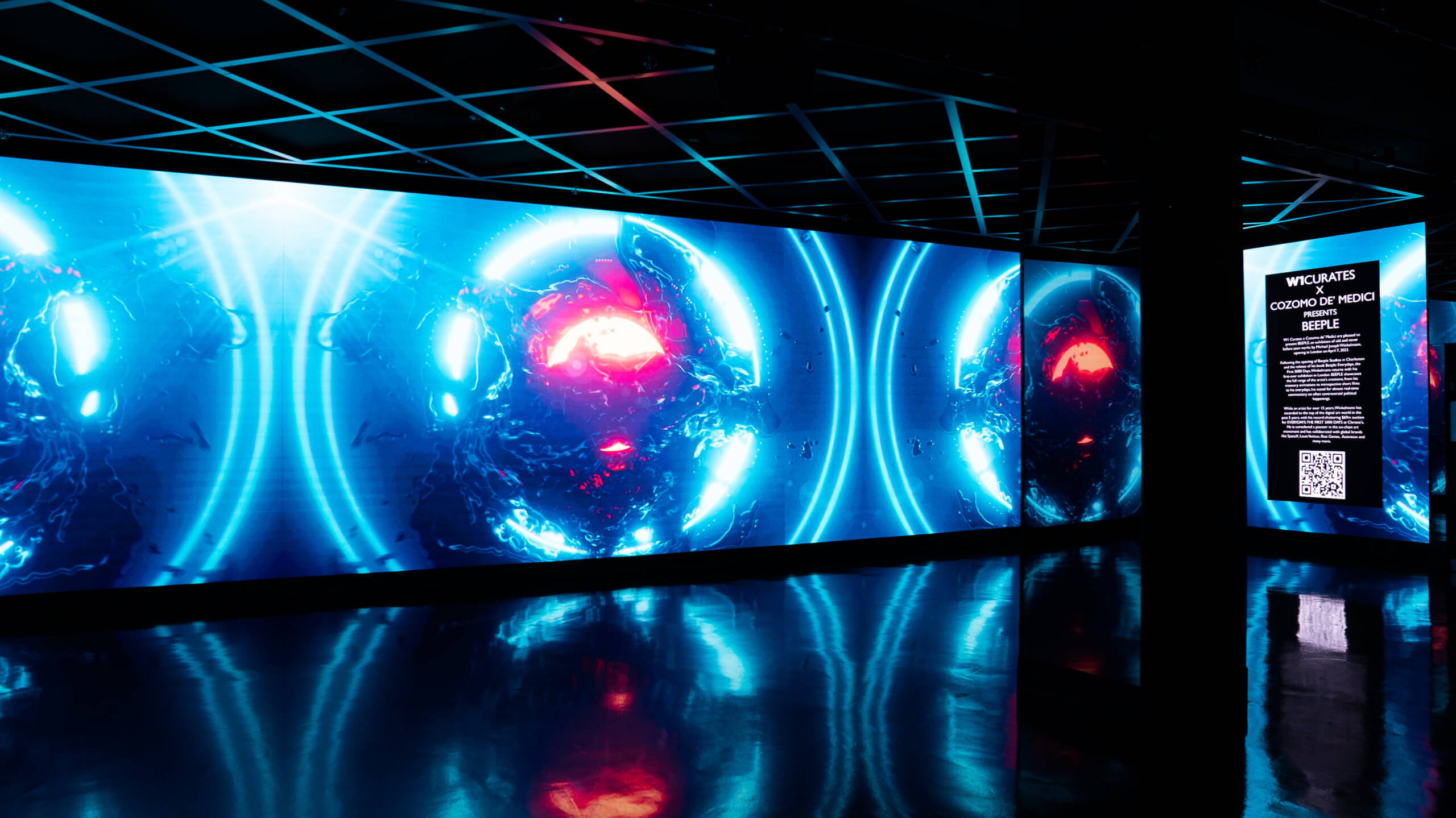

LUX: You said last year that NFTs were not for you right now. What’s your view of NFTs now?

KAWS: They weren’t for me at the time. I haven’t made any. I find it fascinating – it’s great to see so many people so excited about making work, but I think a lot of the interest is commercial interest, and that’s kind of a buzzkill. With the recent decline in the crypto and NFT markets, I think it’s actually going to get more exciting; people who are doing it are going to do it because they feel the need to make it, not because they’re interested in financial gain. It’s been a rough few months for that world, but I think the good stuff will start to come.

LUX: Is it important to you that big collectors are treasuring your works and they are exchanging hands for big prices at auctions?

KAWS: The price of something is not going to change the work. Once the artwork goes into the world, it’s going to take on different lives and you can’t control that. I don’t know, I don’t spend too much time thinking about it or worrying about it. In my mind, when a work is finished, that is the moment of success for me.

LUX: Should we call you an artist? Or, with everything you have done with brands, are you something else?

KAWS: I would just keep it as artist.

Find out more: kawsone.com

This article first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2022/23 issue of LUX

This is 50% Chardonnay, 50% Pinot Noir, all Grand Cru. This is our vision of Grand Cru, and you have a wine which is sculpted. You always have this energy, this freshness which you can find in the Chardonnay; light, delicate thin bubbles. It is pushed by the structure of the Pinot Noir; the two grapes are perfectly integrated; they are one. I think that all our wine is precise, super clean and in a way they are also speaking to the art which is for us very important. It has to be a pleasure!

This is 50% Chardonnay, 50% Pinot Noir, all Grand Cru. This is our vision of Grand Cru, and you have a wine which is sculpted. You always have this energy, this freshness which you can find in the Chardonnay; light, delicate thin bubbles. It is pushed by the structure of the Pinot Noir; the two grapes are perfectly integrated; they are one. I think that all our wine is precise, super clean and in a way they are also speaking to the art which is for us very important. It has to be a pleasure! Taittinger Les Folies de la Marquetiere

Taittinger Les Folies de la Marquetiere But there is a limit – we will never be able to produce a lot. We only take the grapes of the five villages in the Côte des Blancs, and with that we only use the first pressed juice, to have the purest juice, to be able to make it age in the long term.

But there is a limit – we will never be able to produce a lot. We only take the grapes of the five villages in the Côte des Blancs, and with that we only use the first pressed juice, to have the purest juice, to be able to make it age in the long term. Taittinger Comtes de Champagne Rosé 2007

Taittinger Comtes de Champagne Rosé 2007