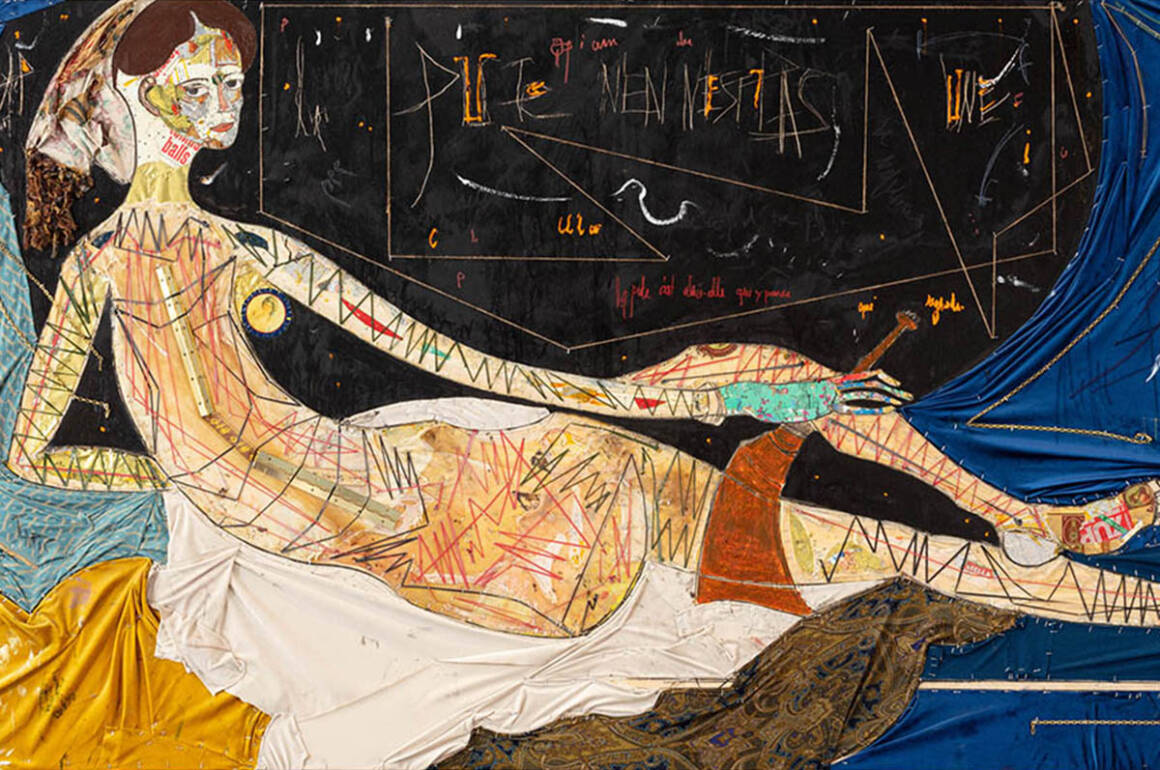

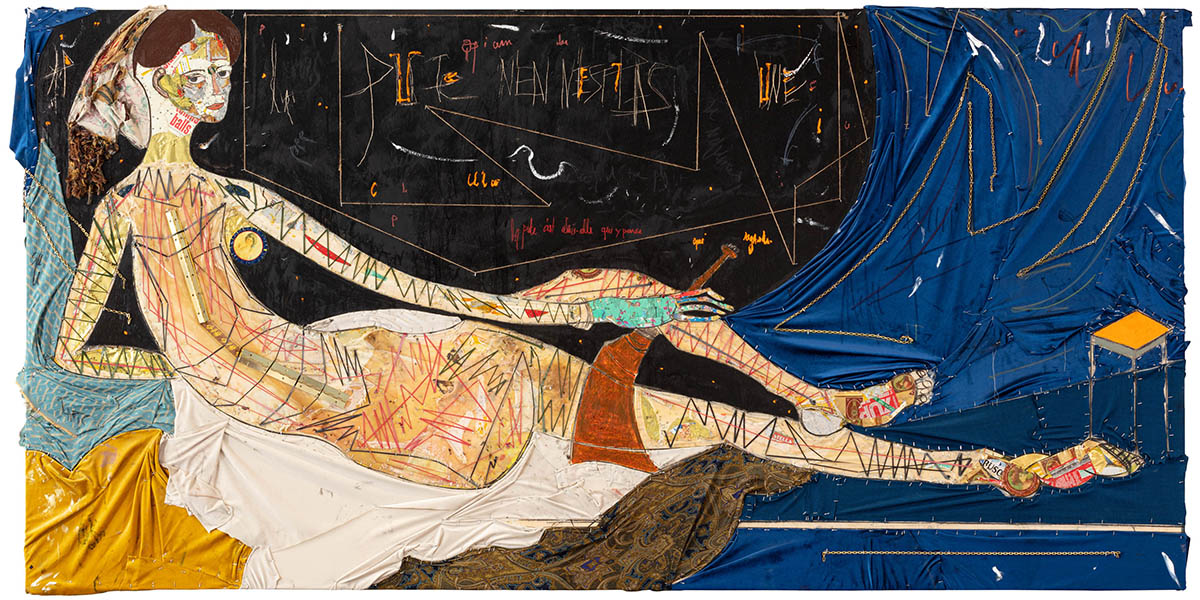

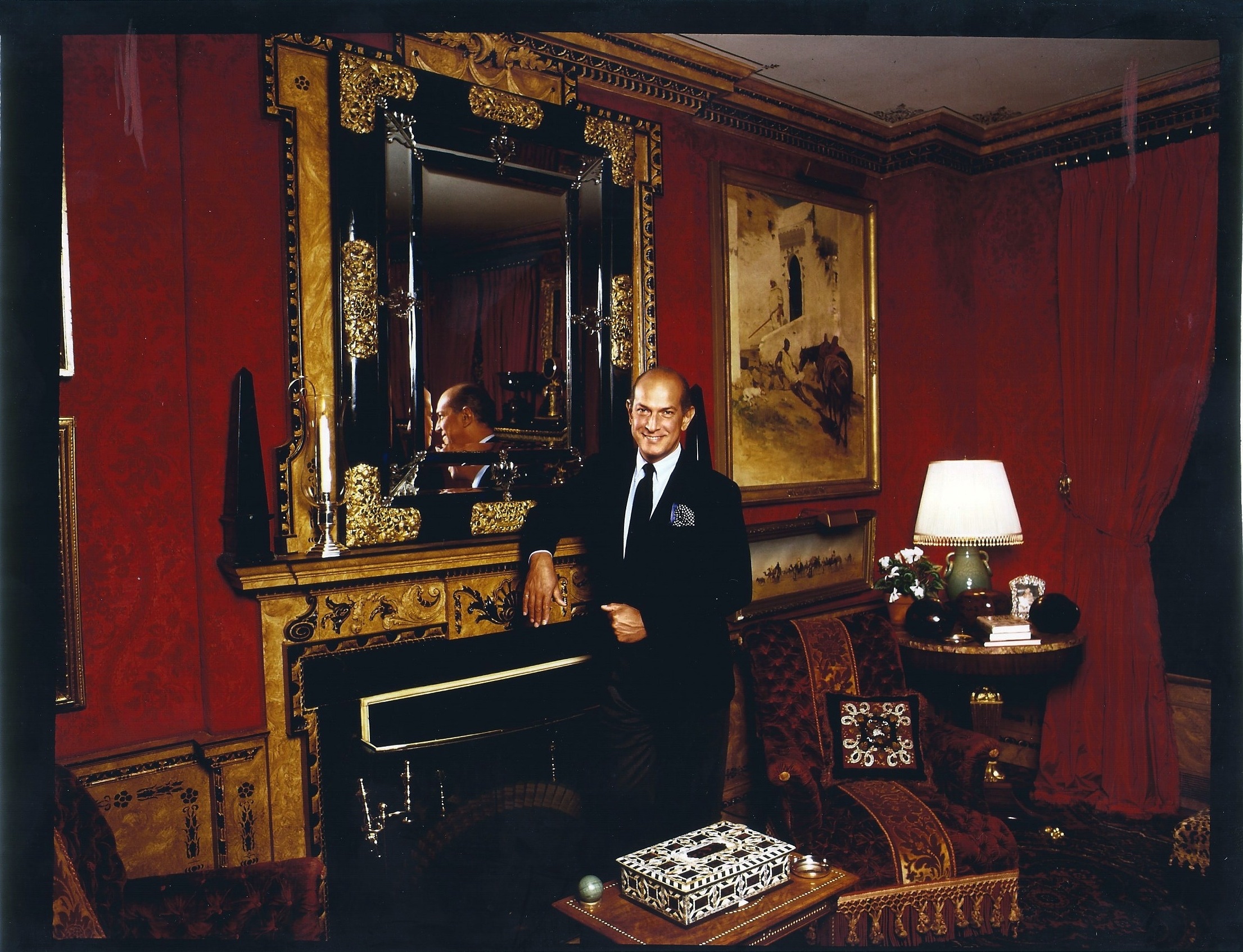

Durjoy Rahman with Kiefer’s Cell (Diptych) (1999) by Atul Dodiya. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

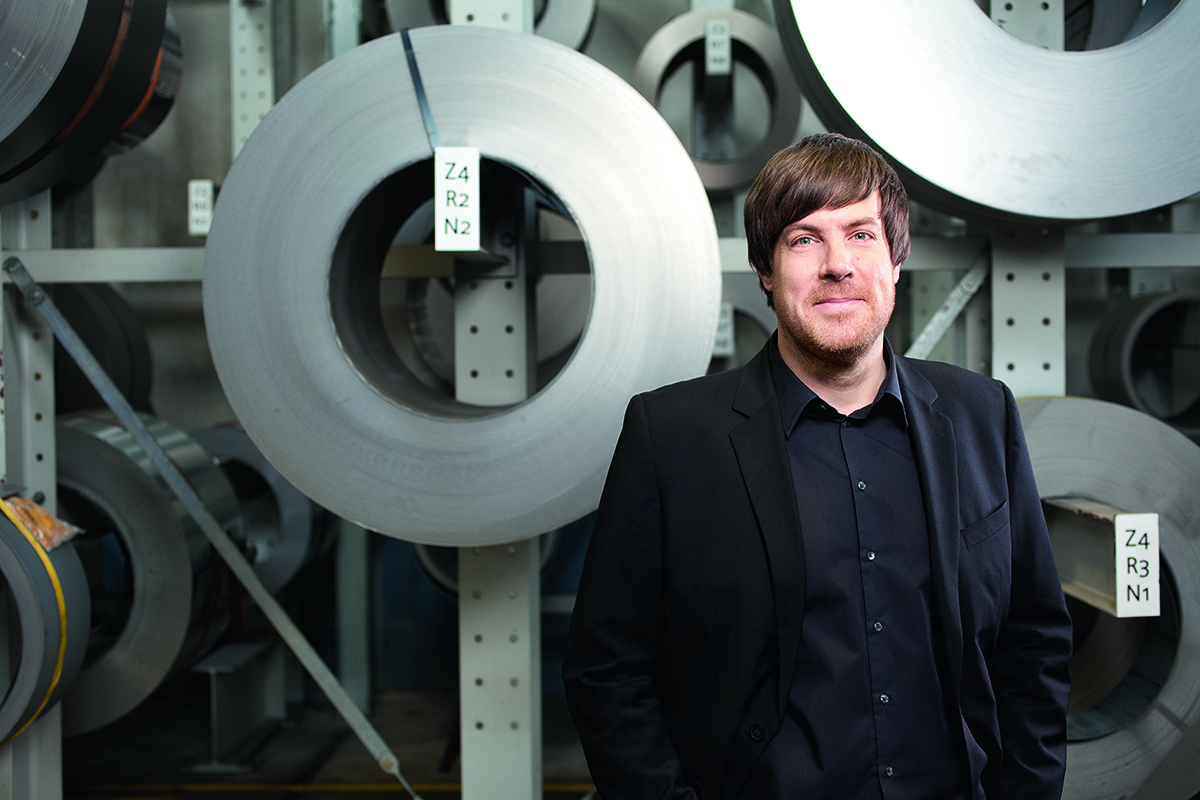

Bangladeshi entrepreneur and art collector Durjoy Rahman is on a mission to make the world a better place through artistic dialogue and cultural collaborations between artists from the Global North and South. Rebecca Anne Proctor reports

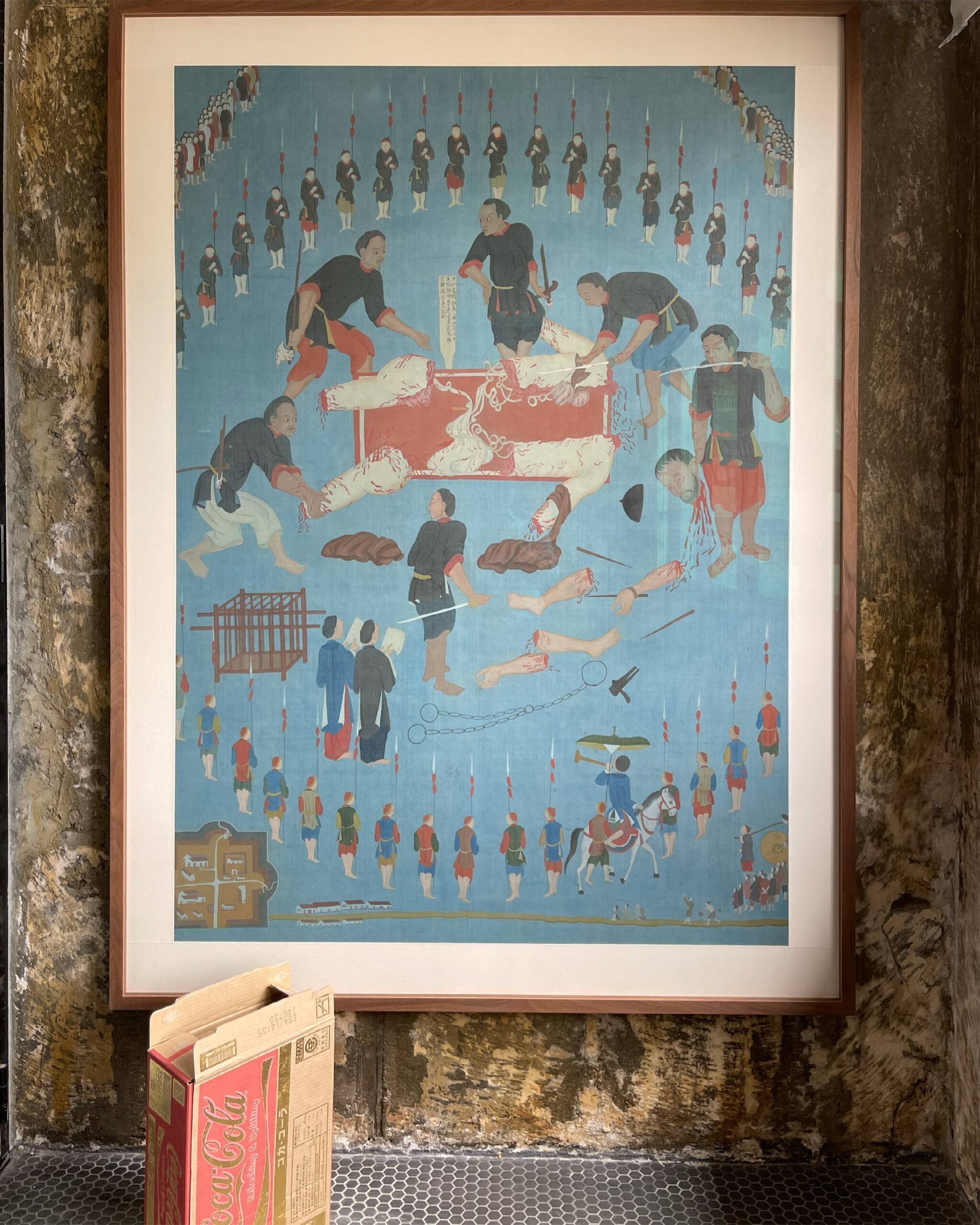

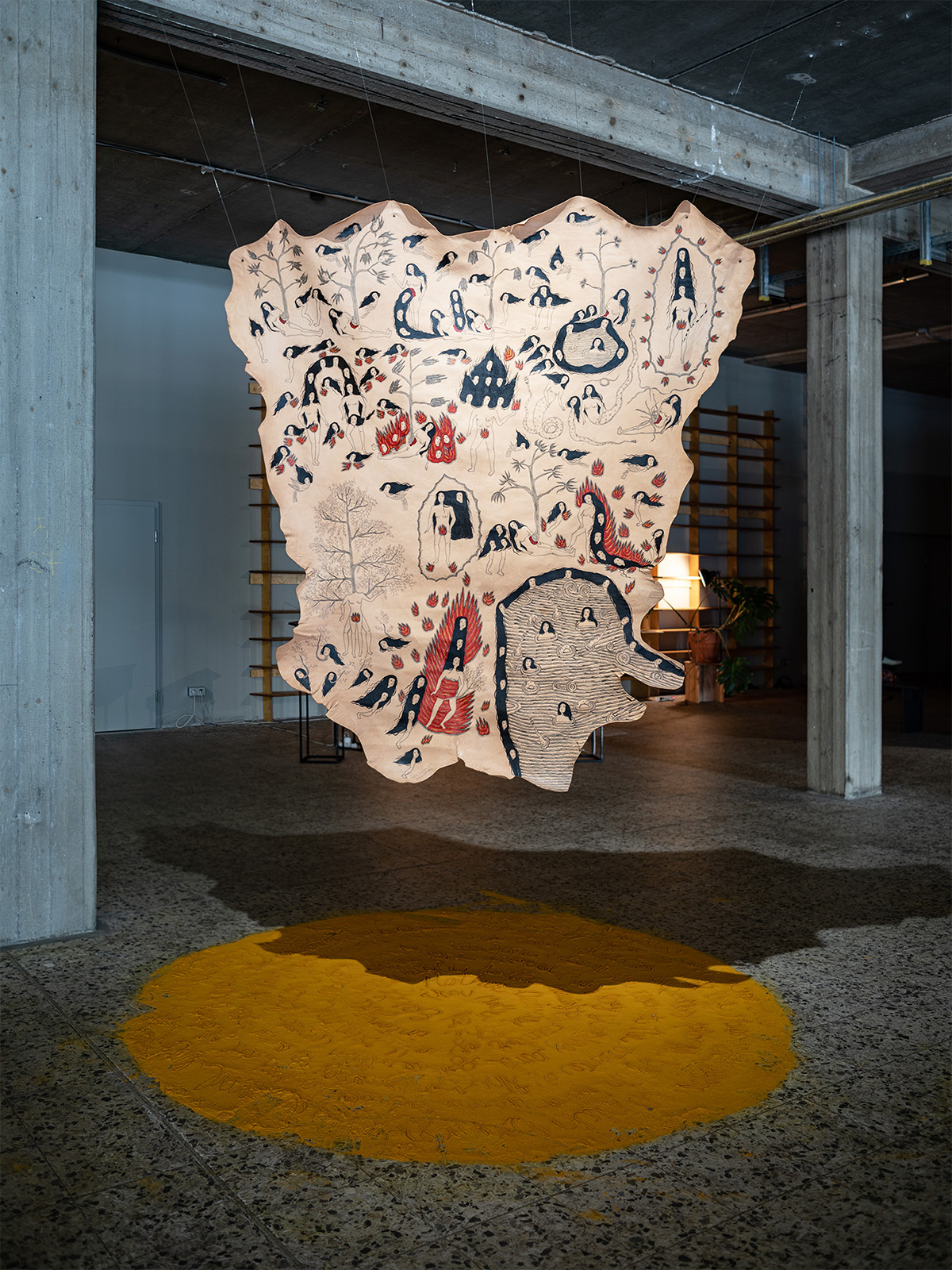

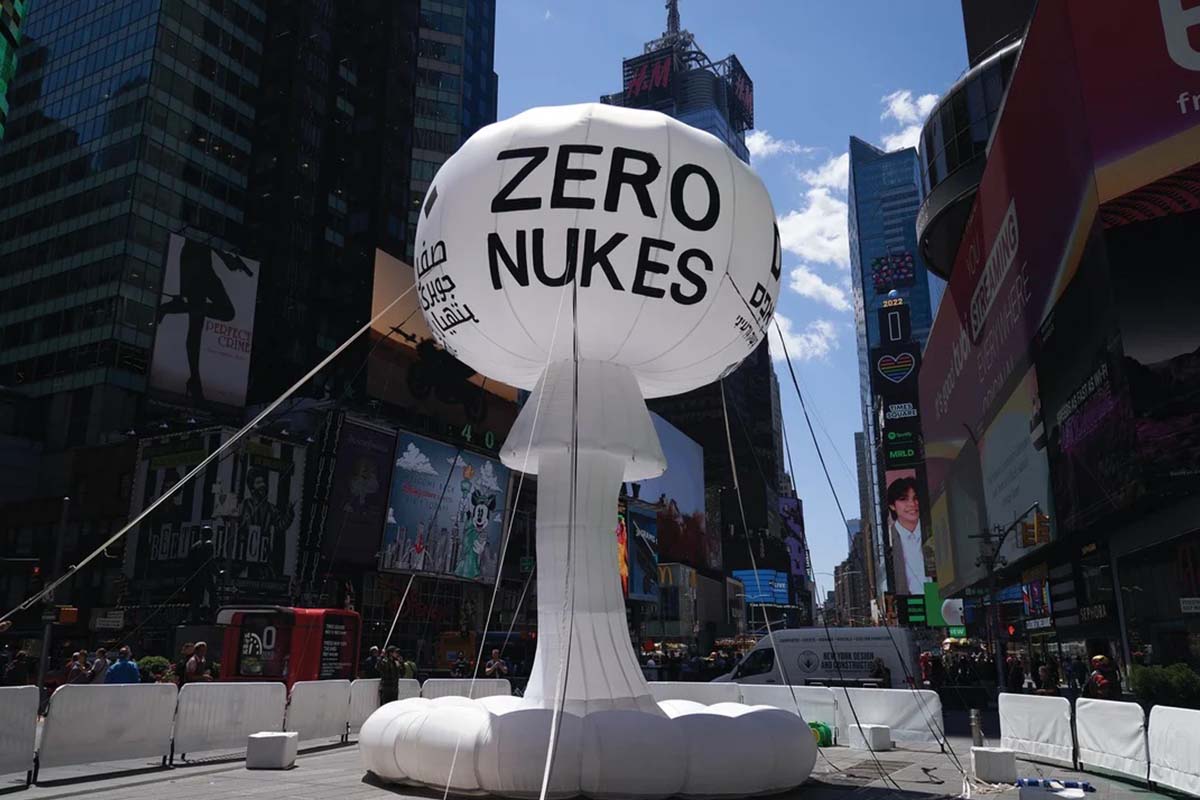

It was mid March 2021 and the world was slowing waking up from a long sleep after the global lockdowns and travel restrictions that had been enforced to curb the deadly coronavirus pandemic. Dubai, the megalopolis Gulf city, was already open and it was kicking off with Art Dubai, one of the first in-person art fairs the art world experienced in the past year. As big art-world personalities flocked to the United Arab Emirates, so too did a rising star from Dhaka, Bangladesh – Durjoy Rahman. The art collector and textile and garment entrepreneur used the occasion of Art Dubai to present one of his latest art initiatives that uses contemporary art to champion social issues. The Dubai Design District featured a large-scale installation of elephants by Bangladeshi artist Kamruzzaman Shadhin and Rohingya craftspeople from the Kutupalong refugee camp. Titled Elephant in the Room, it made its international debut in Dubai. The work, unmissable by those visiting the futuristic Dubai Design District, originated in the desire to forge a dialogue about human and environmental displacement. The Rohingya are a stateless Muslim minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine state thought to number around one million people who remain unrecognised as citizens or as one of the country’s 135 recognised ethnic groups by the country’s ruling party. By exhibiting a work with the involvement of Rohingya people, Durjoy hoped to draw attention to their cause.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

From the Indian subcontinent, the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF), founded in 2018 in Berlin and Dhaka, is one of a handful of collector-led foundations in South Asia working to support creatives, the majority of which have been set up during the past decade. There’s the Bengal Foundation, founded in 1986 and based in Dhaka, which acts as a non-profit and charitable organisation; the Cosmos Foundation, the philanthropic arm of the Cosmos Group conglomerate; the HerStory Foundation, a not-for-profit that supports gender equality through storytelling, illustration, design, and dialogue; and the Samdani Art Foundation (SAF), a private arts trust based in Dhaka, founded in 2011 by collector couple Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani. In neighbouring India, several collector-led foundations have sought individually and collectively to foster India’s rich art scene. These include the Gujral Foundation, founded by Mohit and Feroze Gujral; Kiran Nadar Museum, founded by collector Kiran Nadar; and the Devi Art Foundation, founded in 2008 by Anupam Poddar and his mother, Lekha Poddar. In Pakistan, the Lahore Biennale Foundation and the Como Museum of Art, the country’s first private museum of contemporary art that opened in 2019, are notable.

Elephant in the Room (2018) by Kamruzzaman Shadin and Rohingya craftspeople from the Kutupalong refugee camp, installed at the Dubai Design District in 2021. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Despite the region’s fast-growing economies, major gaps between rich and poor still exist, as does a lack of infrastructure and funding for arts and culture. Art foundations such as the DBF have been pivotal in supporting artistic research and practice. What defines these foundations, which are critical to the expansion of modern and contemporary South Asian discourse, is their ability to take risks and to experiment. For a world increasingly defined by borders, this approach is crucial and one that Durjoy has not taken lightly over the past several years. Cultural awareness and collaboration has been key to his vision for the DBF’s mission.

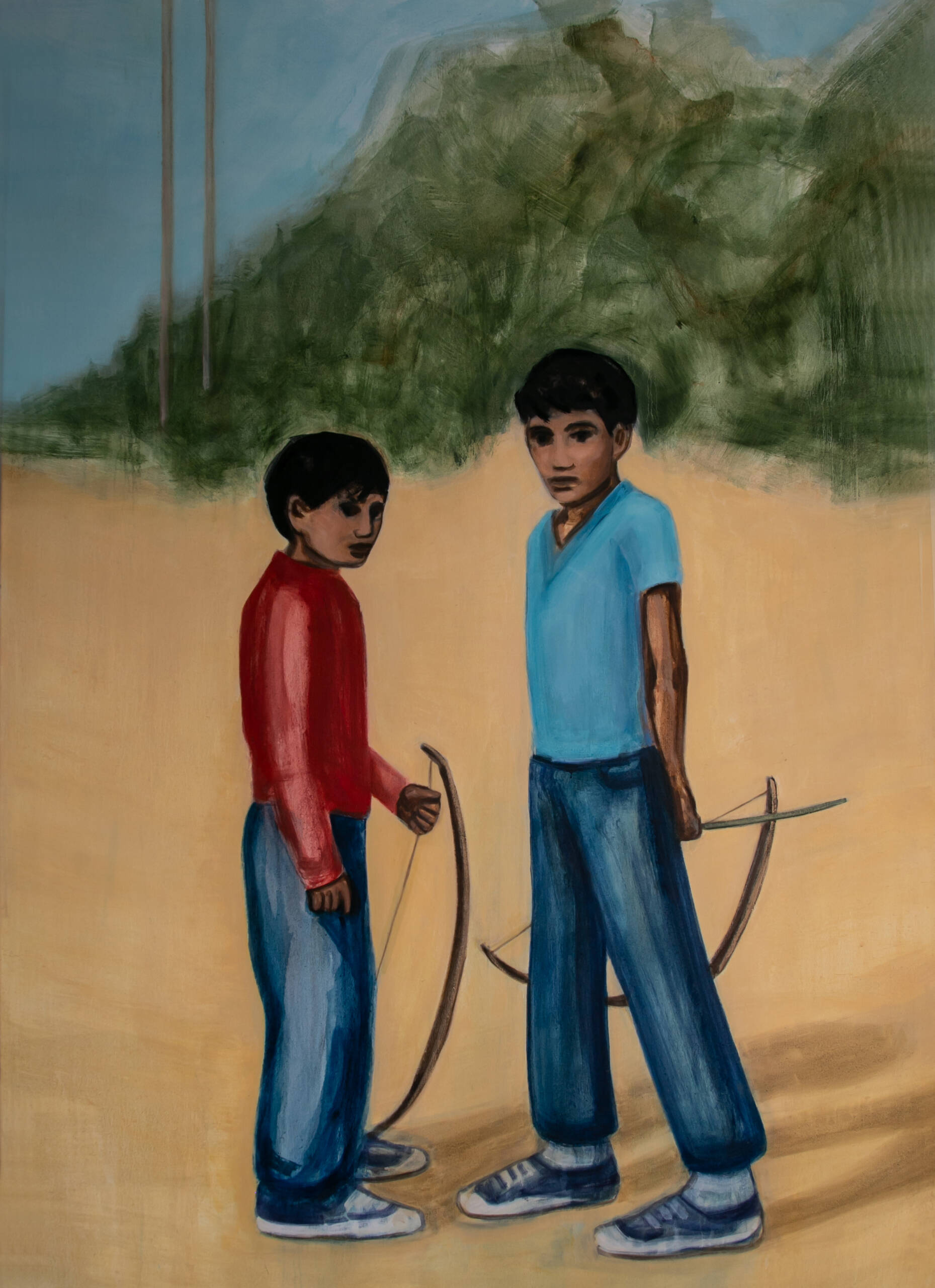

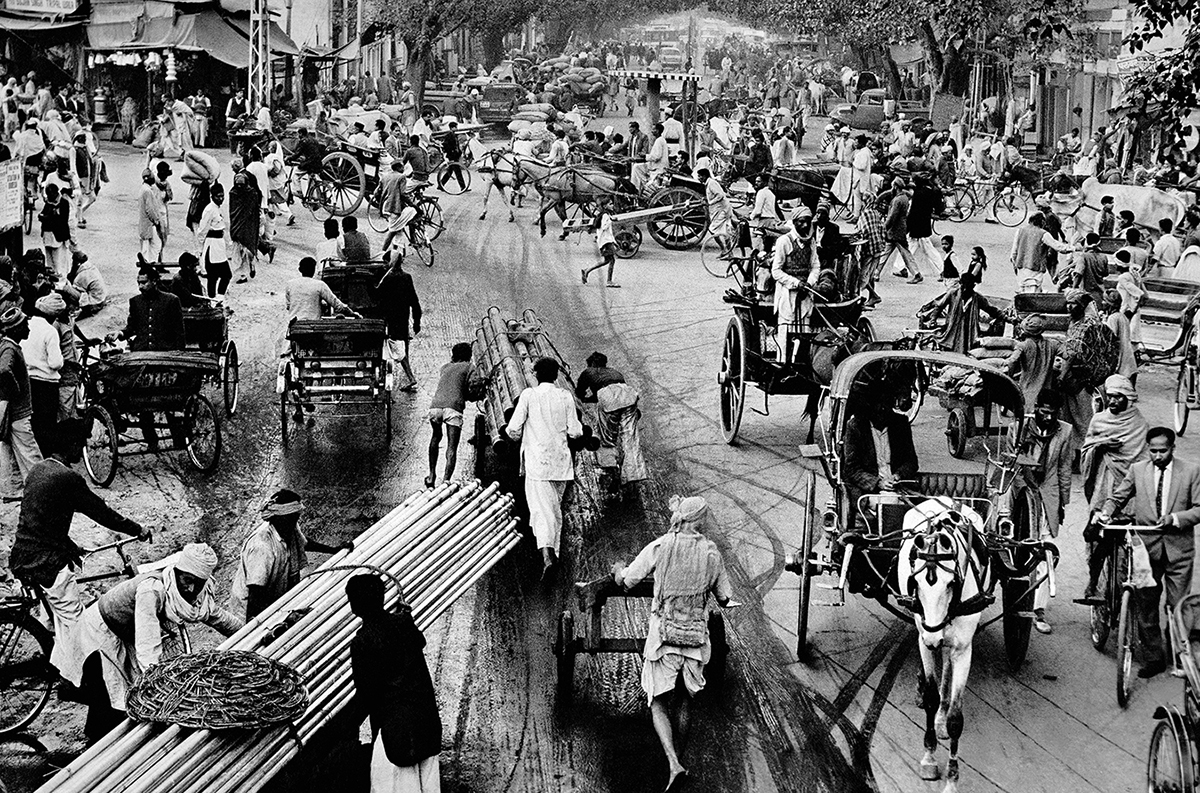

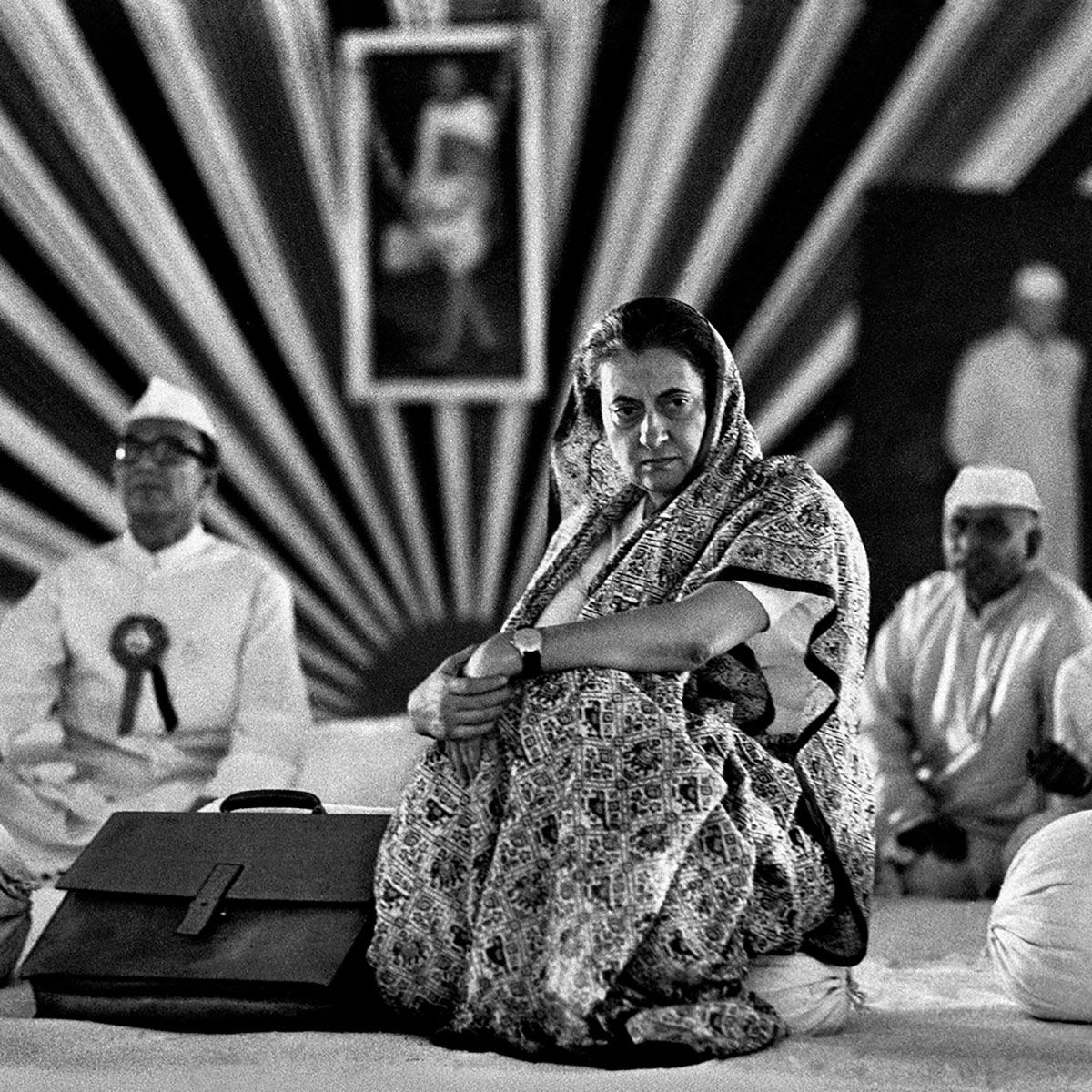

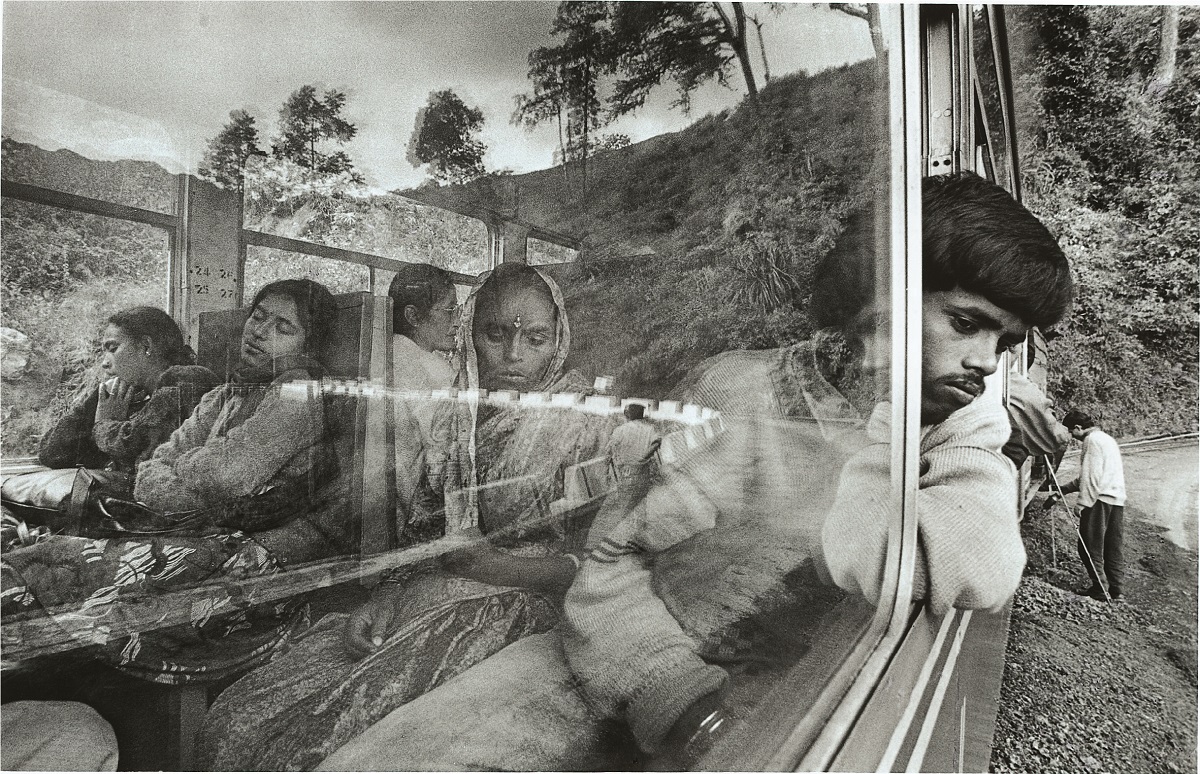

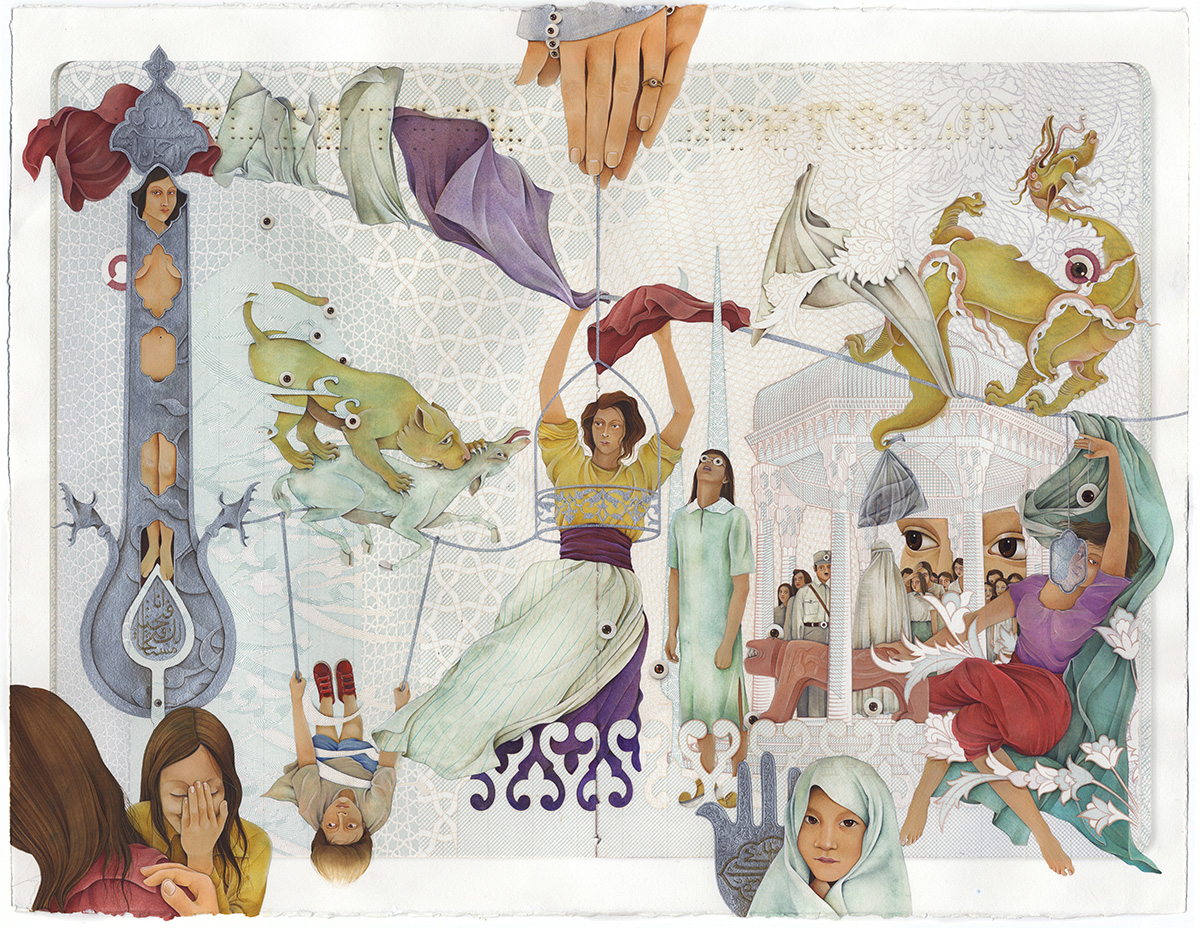

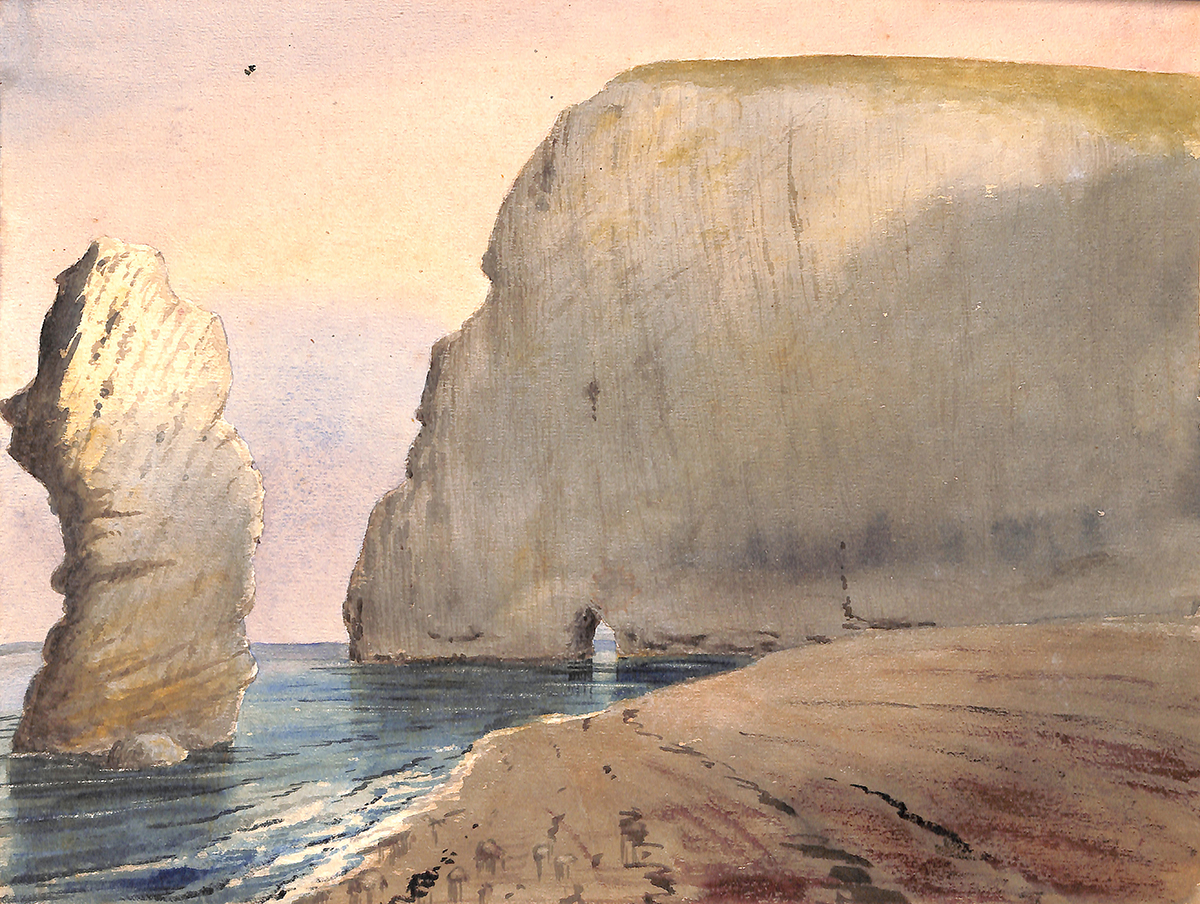

His support for the exhibition ‘Homelands: Art from Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan’, which opened at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge in 2019, is a case in point. Through sculpture, painting, performance, film and photography, the exhibition told the stories of migration and resettlement in South Asia and internationally, engaging with the painful memories of displacement and the challenging notion of ‘home’ following the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 and the independence of Bangladesh in 1971.

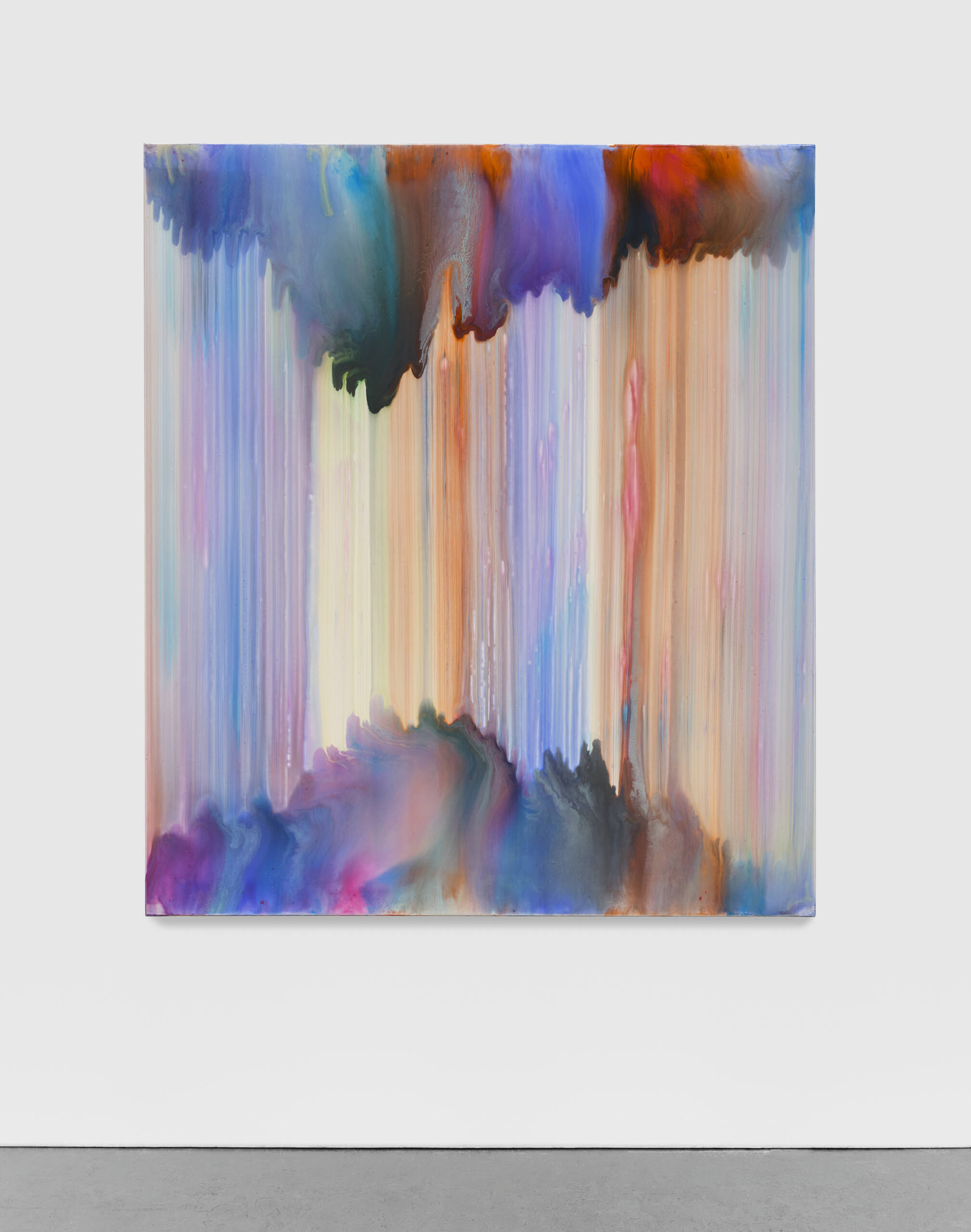

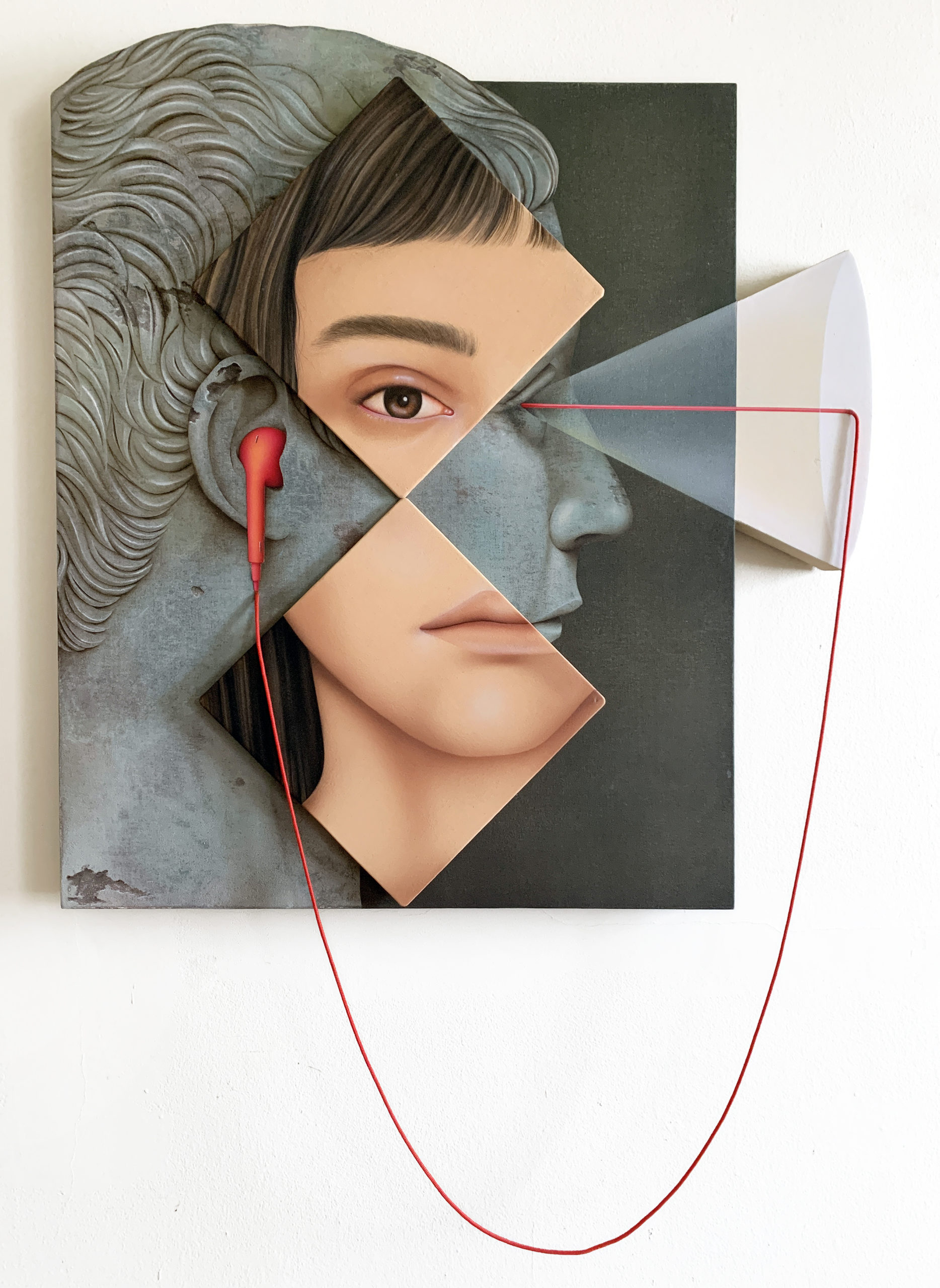

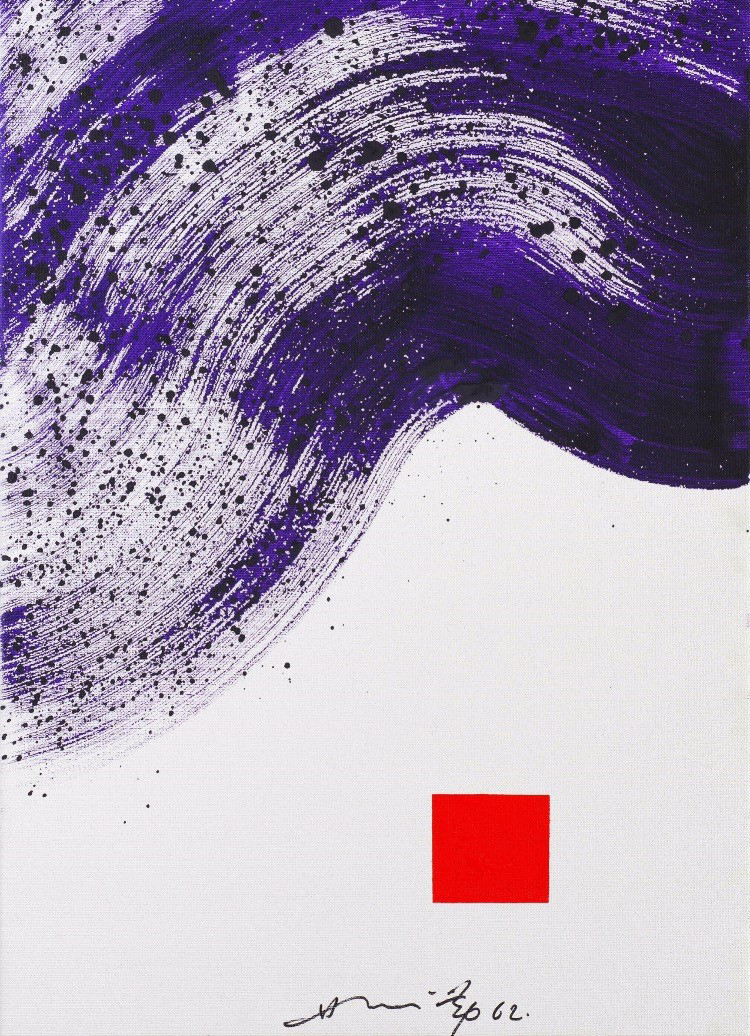

Gbor Tsui (2019) by Serge Attukwei Clottey. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Passionate and energetic, Durjoy never stops, not even during a global pandemic. In a year when many art collectors, galleries and institutions had to do business at a slower pace, Durjoy was busier than ever in Dhaka. The textile entrepreneur, who runs the Bangladeshi garment and textile-sourcing business Winners Creations Ltd, was actively staging new exhibitions, online and live, to support his foundation. Its mission is to promote art from South Asia and beyond, part of the so-called Global South, to forge a critical dialogue within an international context.

Cultural exchange, particularly between artist and arts practitioners from South Asia and beyond, is paramount to the DBF’s vision. Its recent projects, such as ‘No Place Like Home’, a Rohingya art exhibit consisting of Shadhin’s Elephant in the Room and pieces created by Rohingya refugees living in the Kutupalong camp in Bangladesh, aim to raise awareness of the plight of displaced communities, is just one of many that Durjoy and his foundation have initiated over the past three years.

Read more: In the Studio with Idris Khan

“Art creation can keep the conversation going on important issues,” said Durjoy from his office in Dhaka. “The Rohingya crisis is an example. When it first took place, the news was everywhere. Now, three years on and it doesn’t make the headlines. Through exhibition art made by Rohingya we can keep the conversation alive and hopefully it will result in some change.”

Durjoy, who since 1997 has been collecting art with a strong focus on supporting artists from Bangladesh and South Asia, has long believed that artists from the sub-continent haven’t been given the recognition they deserve on the global stage. The first work he bought was by Bangladesh Modernist Rafiqun Nabi, a famous cartoonist and visual artist known for his creation of the character Tokai, a street urchin. “He produced this character to show the everyday struggle in Bangladeshi society,” explains Durjoy. “He used Tokai to express his visions about what was happening around him. I have been a big fan of his ever since I was young.”

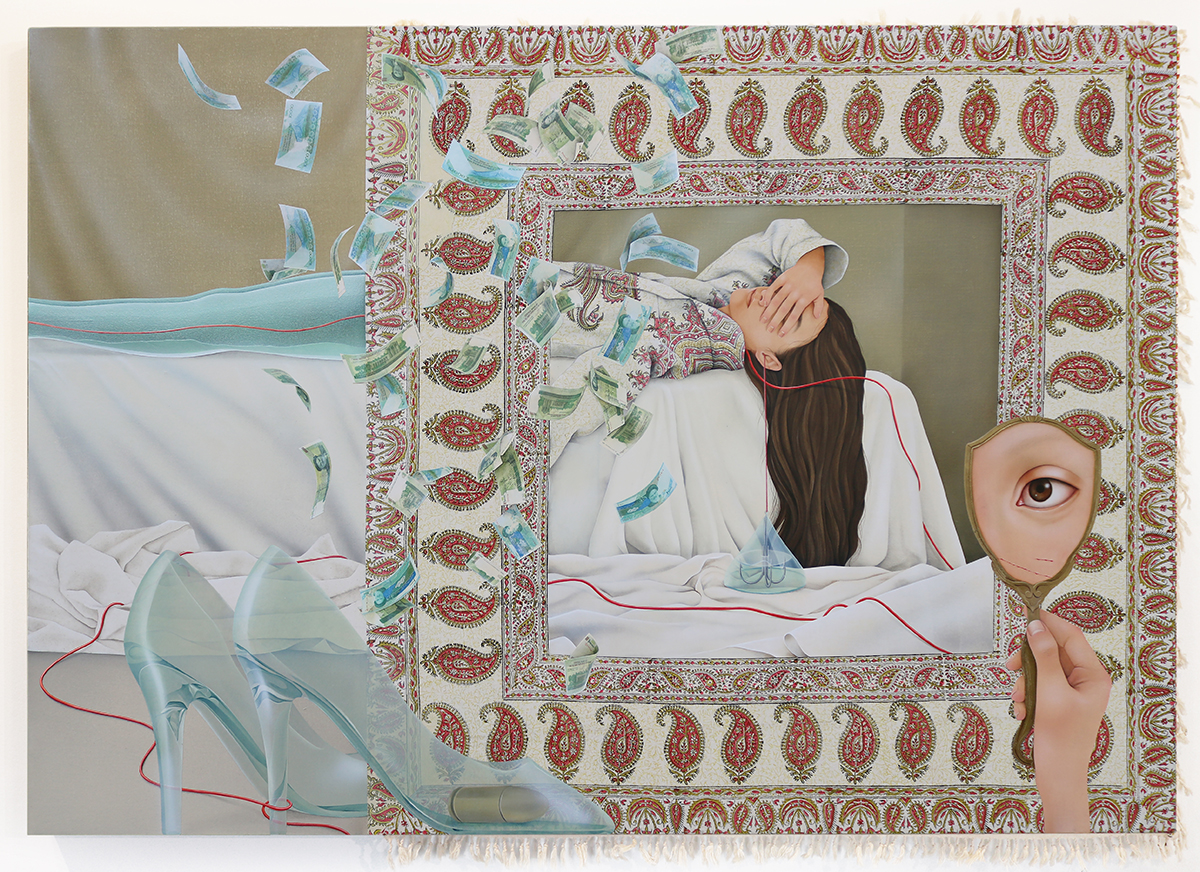

Works in Durjoy Rahman’s collection include Le Baron Fou (2009) and La Baleine (2014) by Novera Ahmed (top), (below, on the wall) Gasp (2013) by Charles Pachter and (sewing machine) 100 Years Old (2018) by Tayeba Begum Lipi. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Durjoy now has more than 70 works by Nabi in his collection of 1,000 or more works of South Asian and international art by the likes of David Hockney, Lucian Freud and Bangladeshi modernists such as Safiuddin Ahmed, as well as South Asian antiques including Ghandharan art and works from the Pala Dynasty dating from the 9th to 11th centuries in Bengal. His collection exemplifies his worldly interests, his love of art and other cultures, and his desire to bring artists from around the world together in unison and creative dialogue. Since his first purchase of Nabi’s work, he has sought to support and collect works by emerging and established Bangladeshi artists in particular, which has become the prime objective of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation.

Over the years, Durjoy noticed a shift in attention from the global art community towards what was taking place in South Asia. “The heightened curiosity towards the East and what is taking place has influenced many artists from the sub-continent to produce works that are more socially charged, that illuminate post-colonial thought and impressions and the continual struggle with notions of identity and statehood,” Durjoy explains. In 2018 he finally took the plunge and established his own foundation with the mission to further the visibility of artists from the Global South – those, as he says, who are often disadvantaged, who don’t come from areas with much art education or infrastructure. Durjoy staged projects, art residencies and exhibitions that support his cause and, importantly, foster creative and cultural dialogue between the artists of South Asia and other areas in the Global South with those elsewhere in the world.

Read more: Helga Piaget on educating the next generation

“I sensed that there needed to be a platform that could represent artists from South Asia as I felt they had not yet been recognised internationally in the way that they should have been,” he says. He admits that at first it was challenging, given his hybrid role of collector and director of a foundation. “It might have looked in the beginning like I was trying to promote the artists in my collection, but then I realised that I could work with artists who were not already in my collection and whose practice and work I appreciated. I truly believe we need to play a more important role in shaping the art system originating from the sub-continent and making a bridge between South Asia and Europe.”

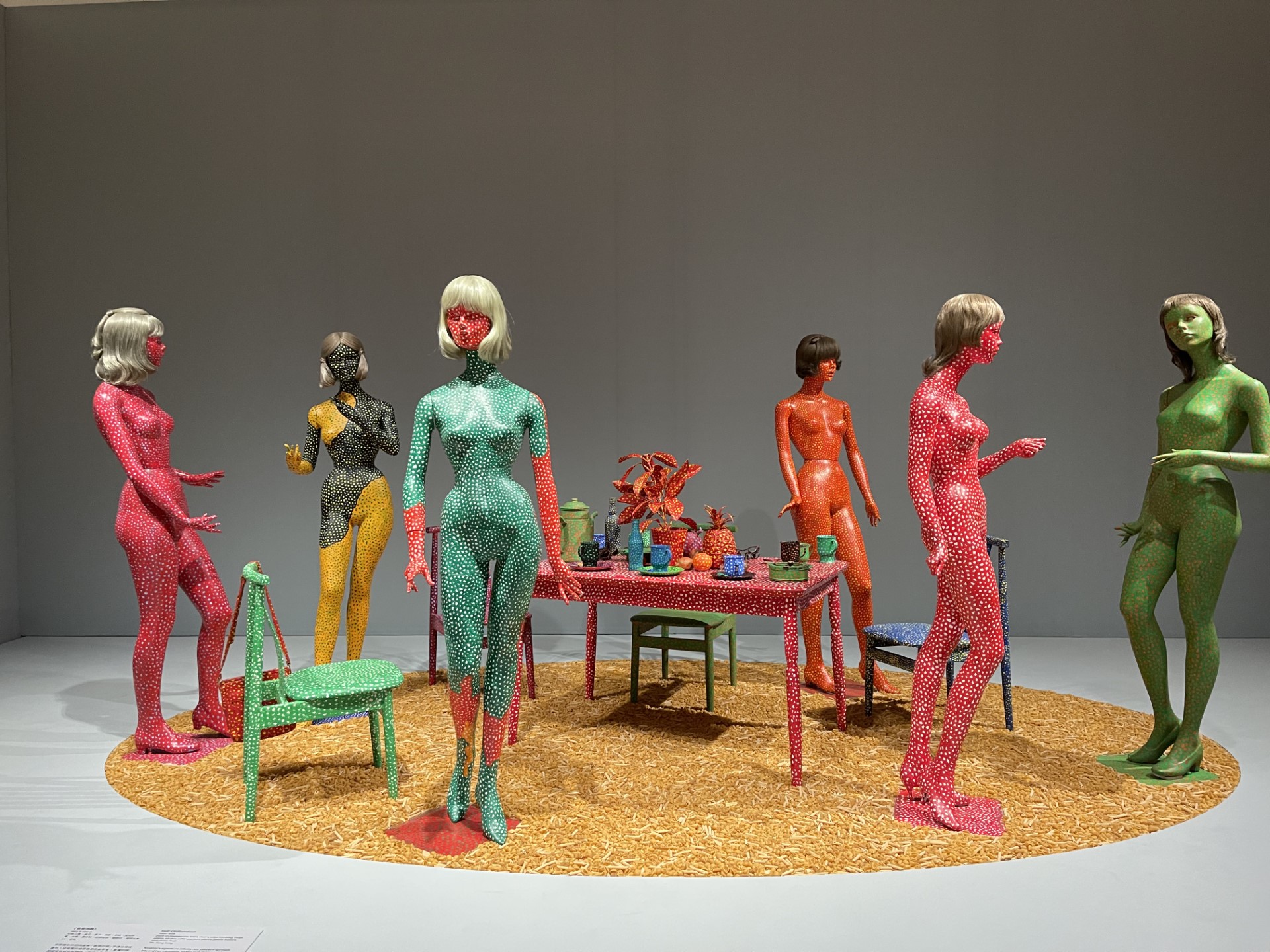

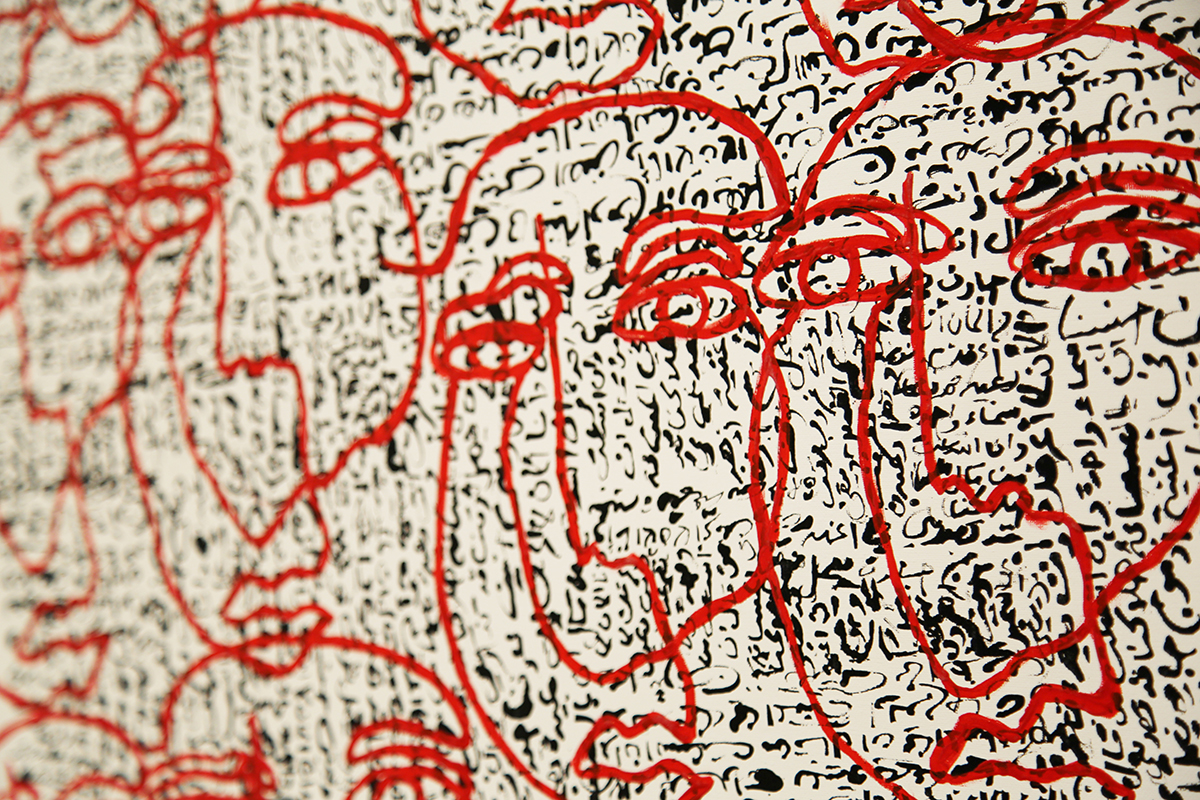

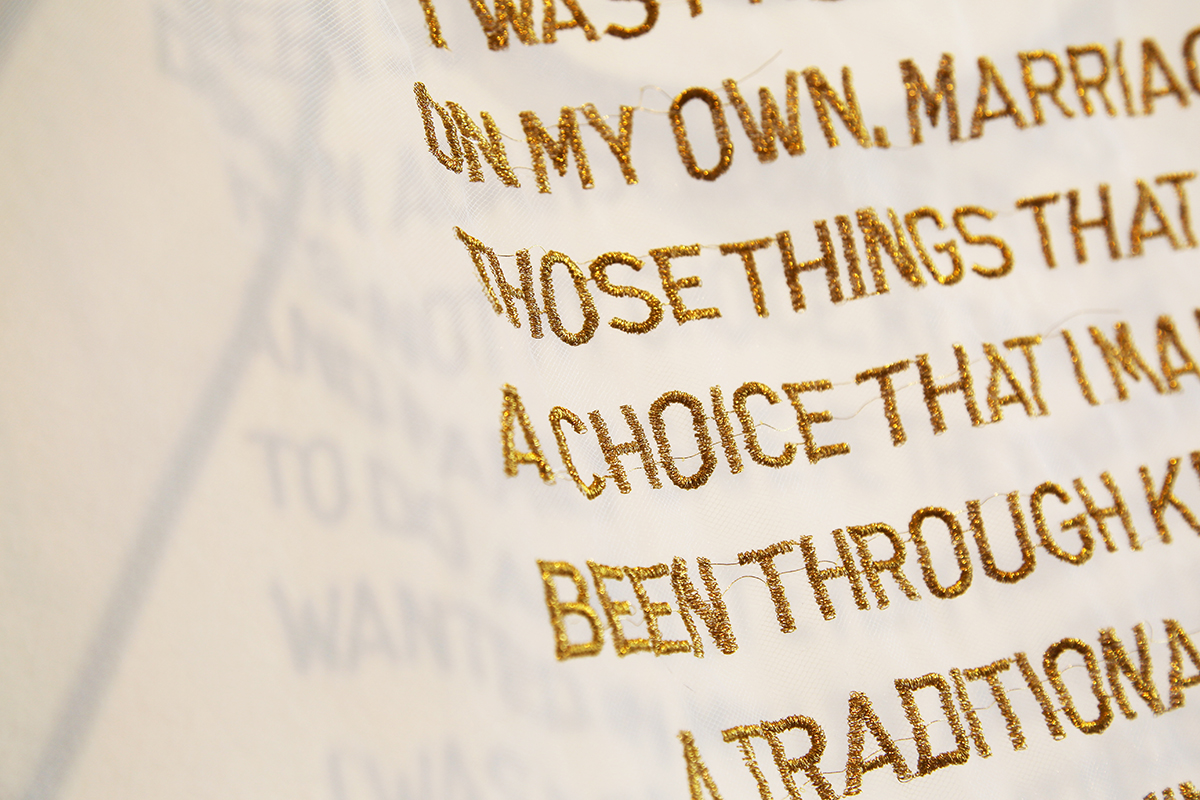

Durjoy first set up a base for the foundation in Berlin in 2018. He was advised on the decision by well-known art advisor Marta Gnyp, known for her work with contemporary African artists. “I admire Durjoy’s curiosity, open-mindedness and his ability to learn extremely fast,” said Gnyp. “This, in combination with the ambitious, focused and very well structured programme of his Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, makes him one of the forces that will shape the future of the South Asian art world.” Later that year Durjoy set up the office in Dhaka where he now has a team of 10 people working for the foundation. He launched his initiative with the unveiling of his donation of Indian artist Mithu Sen’s powerful and nostalgic installation MOU (Museum of Unbelongings) (2011–18) to the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg in Germany as part of their permanent collection. “This was how we made the announcement of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, by having Sen’s installation mark one of the first times that a work by a South Asian artist who happens to be female is in the permanent collection of a European institution,” he adds.

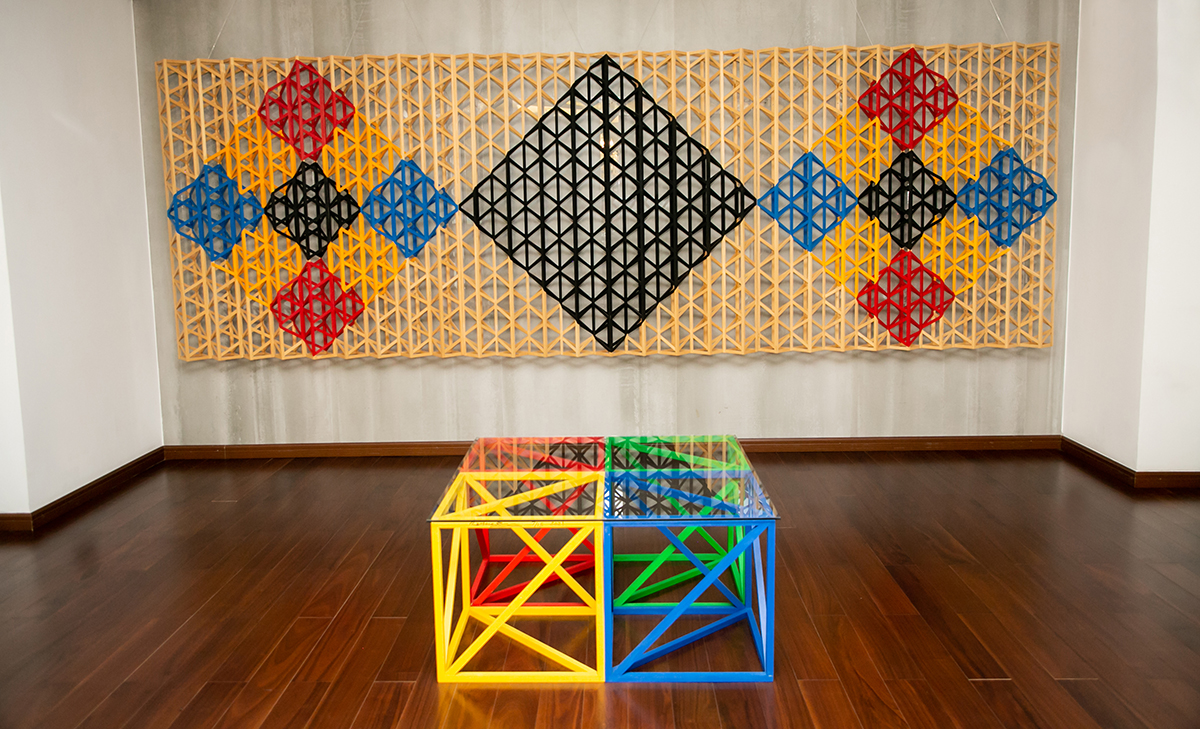

MOU (Museum of Unbelongings) (2011-18) by Mithu Sen. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

This gift to the Kunstmuseum followed a serendipitous meeting between Durjoy and Dr Holger Broeker, head of the collection and senior curator there. Earlier that year, the museum had staged ‘Facing India’, a show marking the first museum exhibition in Germany to present works by women artists from India. The works included in the exhibition, by Vibha Galhotra, Bharti Kher, Prajakta Potnis, Reena Saini Kallat, Mithu Sen and Tejal Shah, questioned the idea of borders of all kinds, whether political, territorial, ecological, religious, social, personal or gender-based. Broeker and Durjoy met by chance one evening in Berlin at GNYP Gallery. “When I asked him about the focus of his collection,” remembers Broeker, “he told me about his project to promote art from the Bangladeshi region and India in Europe and America, and that he himself had already exhibited Western art in Bangladesh in return. He wanted to intensify this idea of cultural exchange within the framework of foundation. An extraordinarily intensive and fruitful communication developed between us and Durjoy donated Sen’s magnificent work to us for our collection.”

Sen’s powerful installation forms the beginning of the Kunstmuseum’s Indian art collection, which now includes works by Tejal Shah, Gauri Gill and Prajakta Potnis. Uta Ruhkamp, the museum’s curator, said, “Mithu Sen finds an international but unconventional visual language that reaches beyond markers like nationality, religion, wealth, skin colour, caste, family, education and language that people use to distinguish themselves from others in both ways, whether feeling superior or inferior. Sen’s installation contains a personal collection of objects and artworks from all over the world. She curated it her way, creating ‘joint’ artworks by combining objects, narrating stories, and suggesting a colourful world free of hierarchies. No label, no categories. It is a global statement, the vision of a world that does not yet exist.”

Artist Serge Attukwei Clottey with his work Gbor Tsui during the exhibition ‘Stormy Weather’ at Arnhem Museum. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

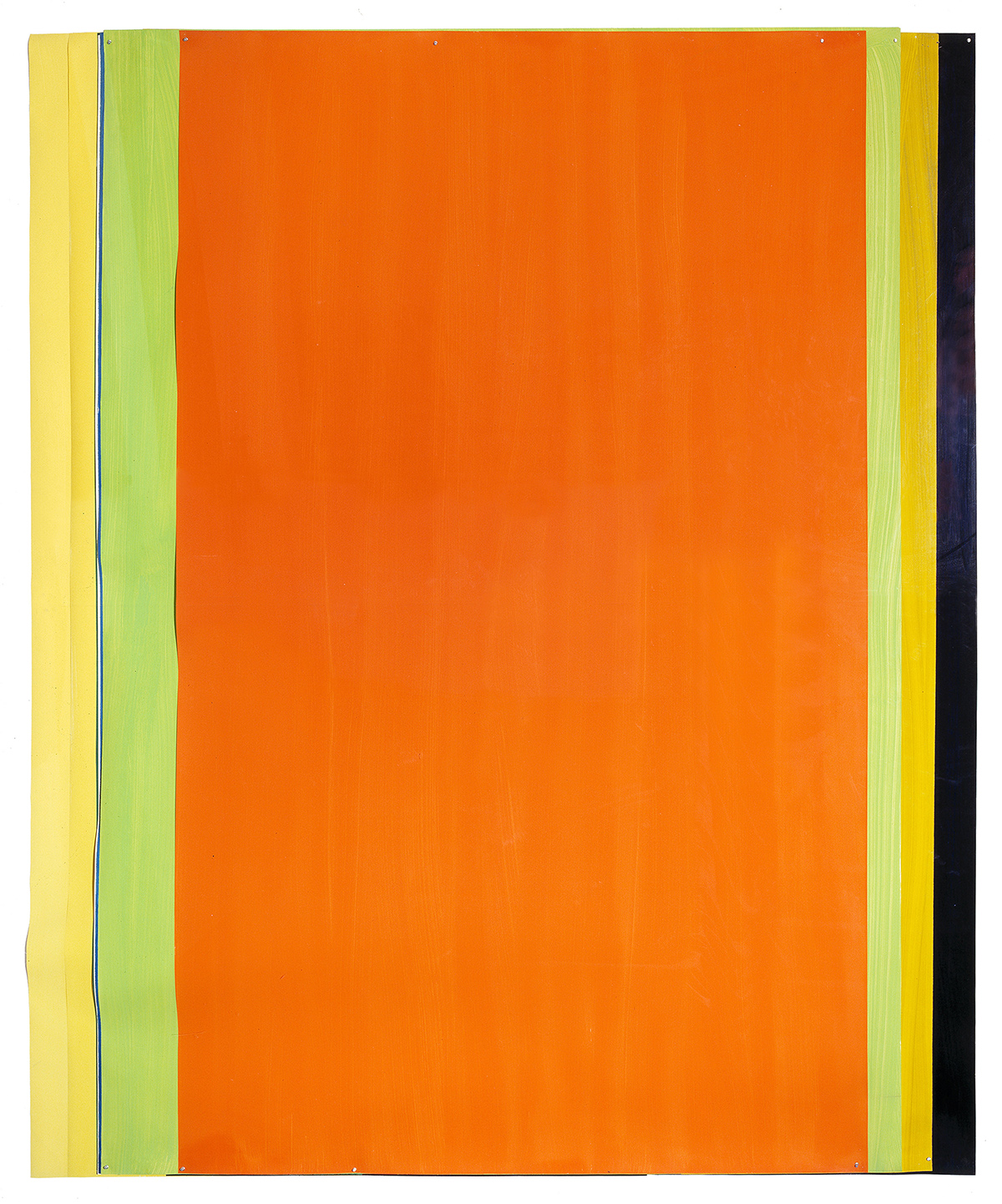

Durjoy, an entrepreneur, lets nothing get in the way of his goals. The number of projects, exhibitions and residencies his foundation has staged in just over three years is startling and impressive. One is example is DBF’s support of Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey in the production of a large artwork featured in the 2019 exhibition ‘Stormy Weather’ at the Arnhem Museum in the Netherlands on the theme of climate change and social justice. After the show, Clottey’s work entered the museum’s collection.

Testament to Durjoy’s desire to support artists in need are two initiatives he launched during the pandemic. One is called Bhumi, which was a collaboration with the Gidree Bawlee Foundation of Arts aiming to help rural communities that make crafts, art and land art. The other programme is Future of Hope, for which Durjoy asked nine artists to create work in response to present global challenges. The works were displayed at the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation last October 2020. “The crux of Durjoy’s mission is to raise awareness of the Global South and supporting and promoting emerging and established artists from that region, but to do so in dialogue with artists from other places around the world,” said Iftikhar Dadi, artist and a professor in the Department of the History of Art and Visual Studies at Cornell University in New York. “I love his energy, dynamism and openness.”

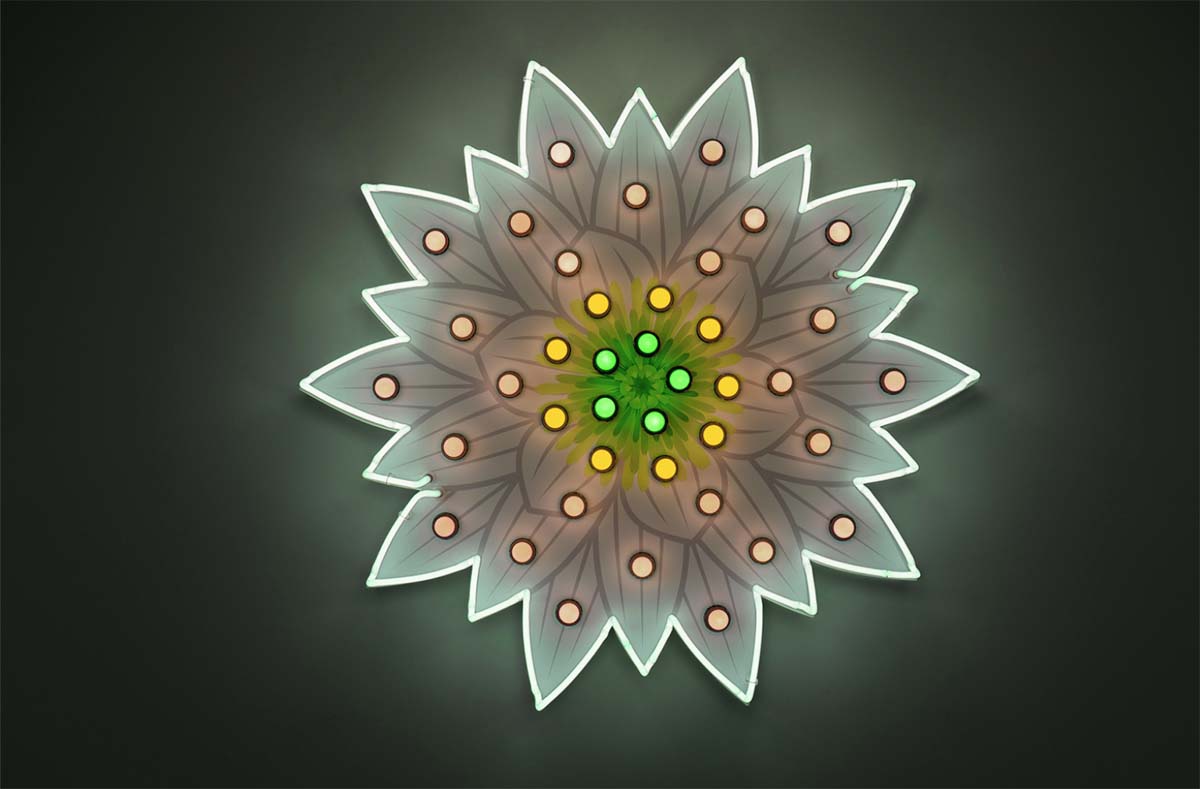

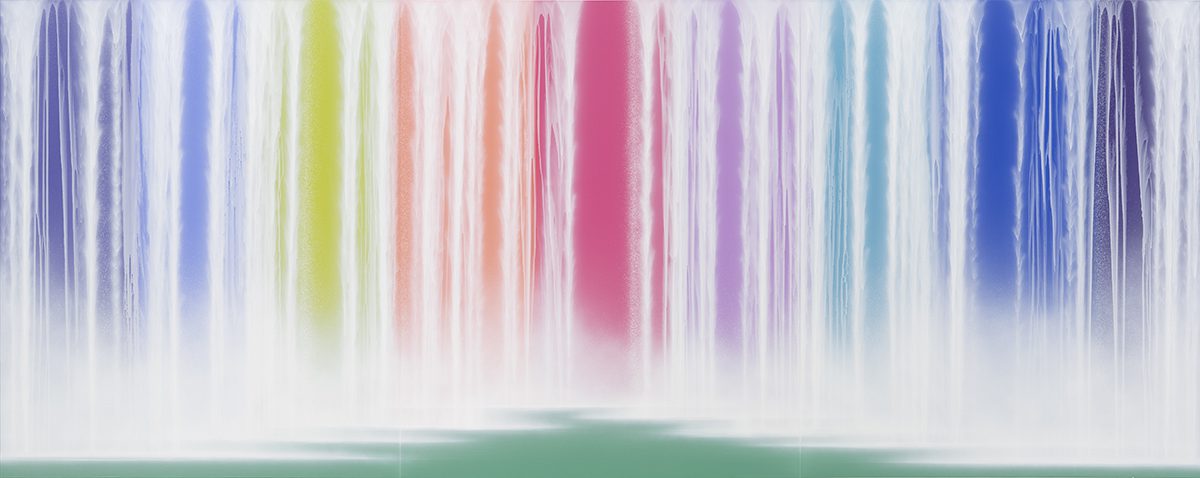

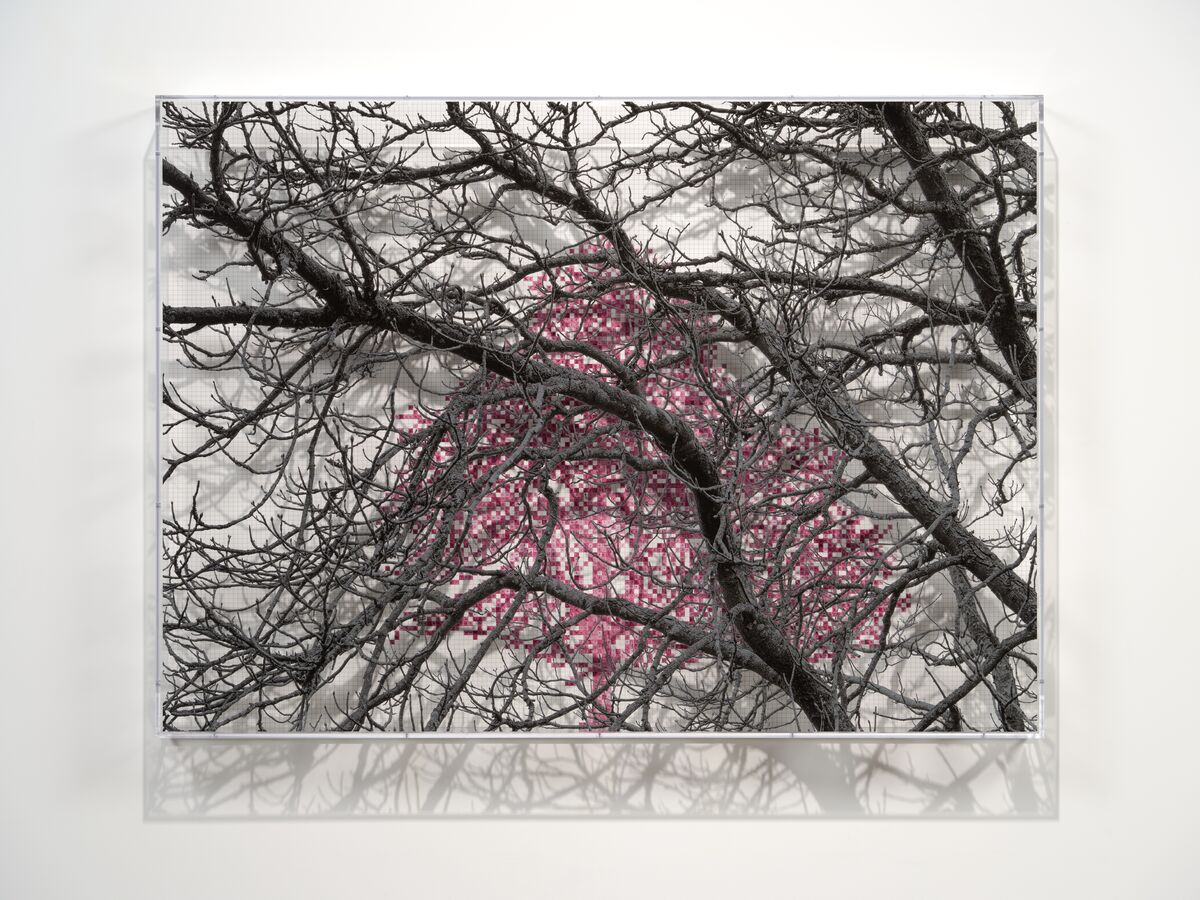

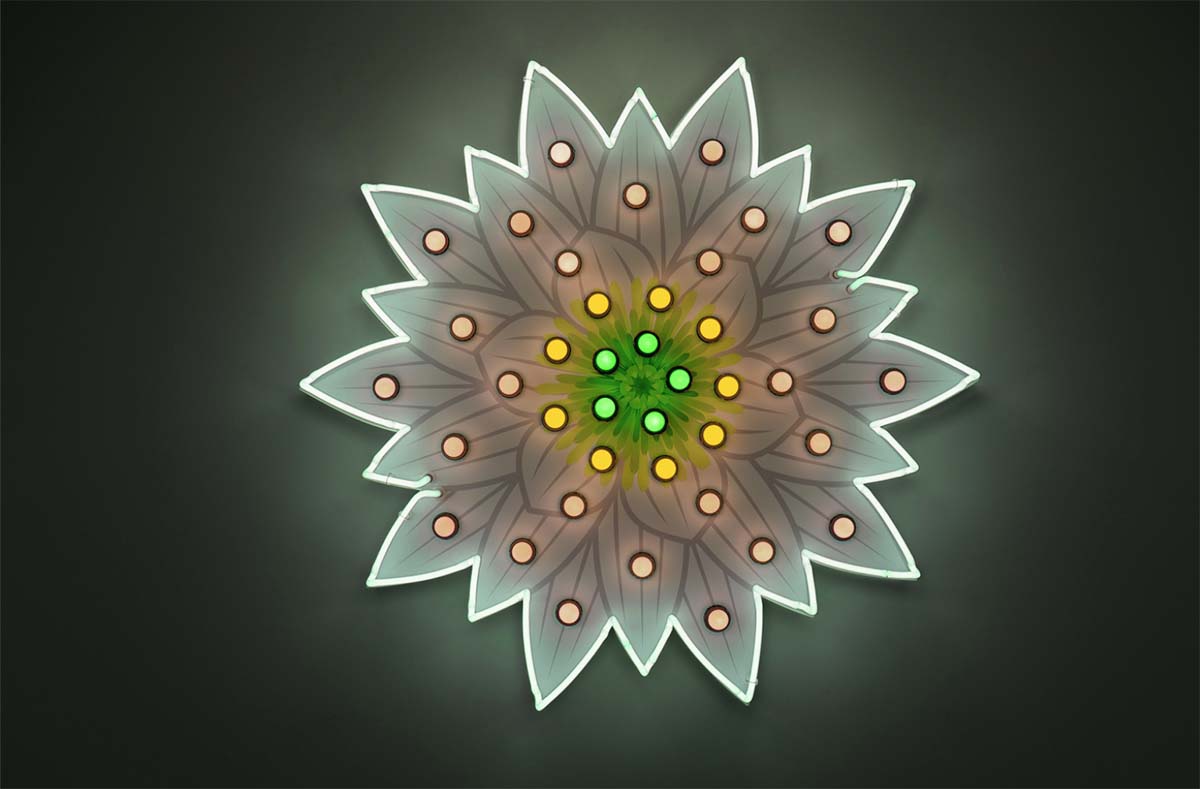

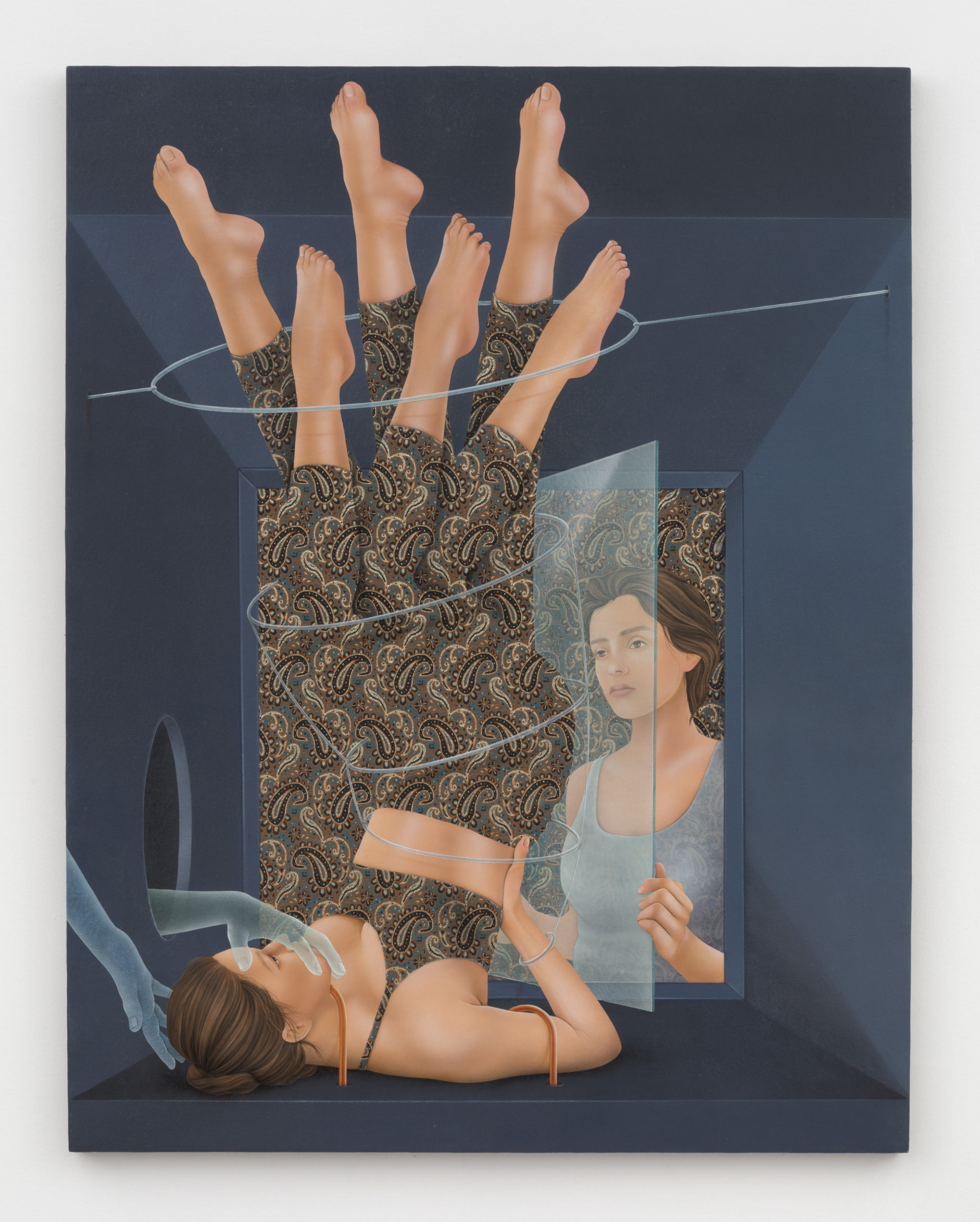

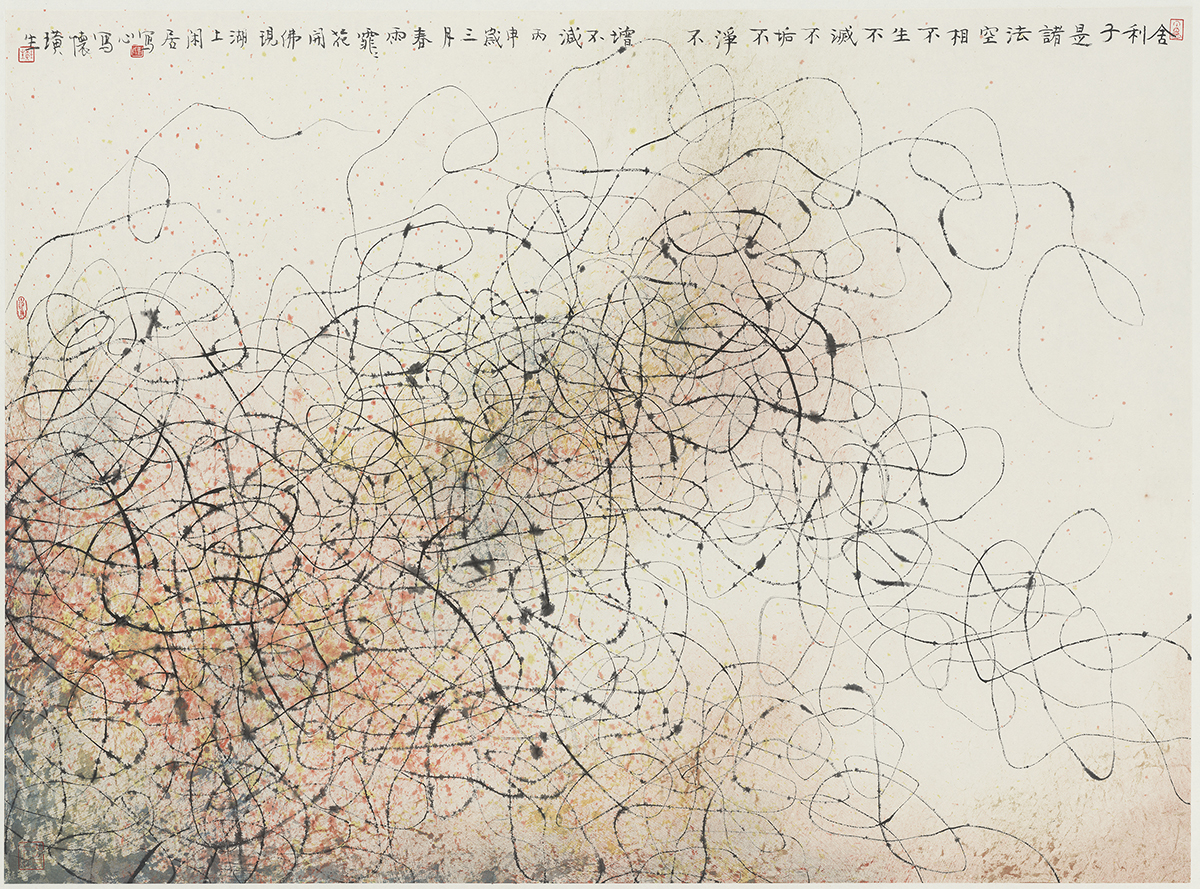

Shapla from the series ‘Efflorescence’ (2013-19) by Iftikhar Dadi and Elizabeth Dadi. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

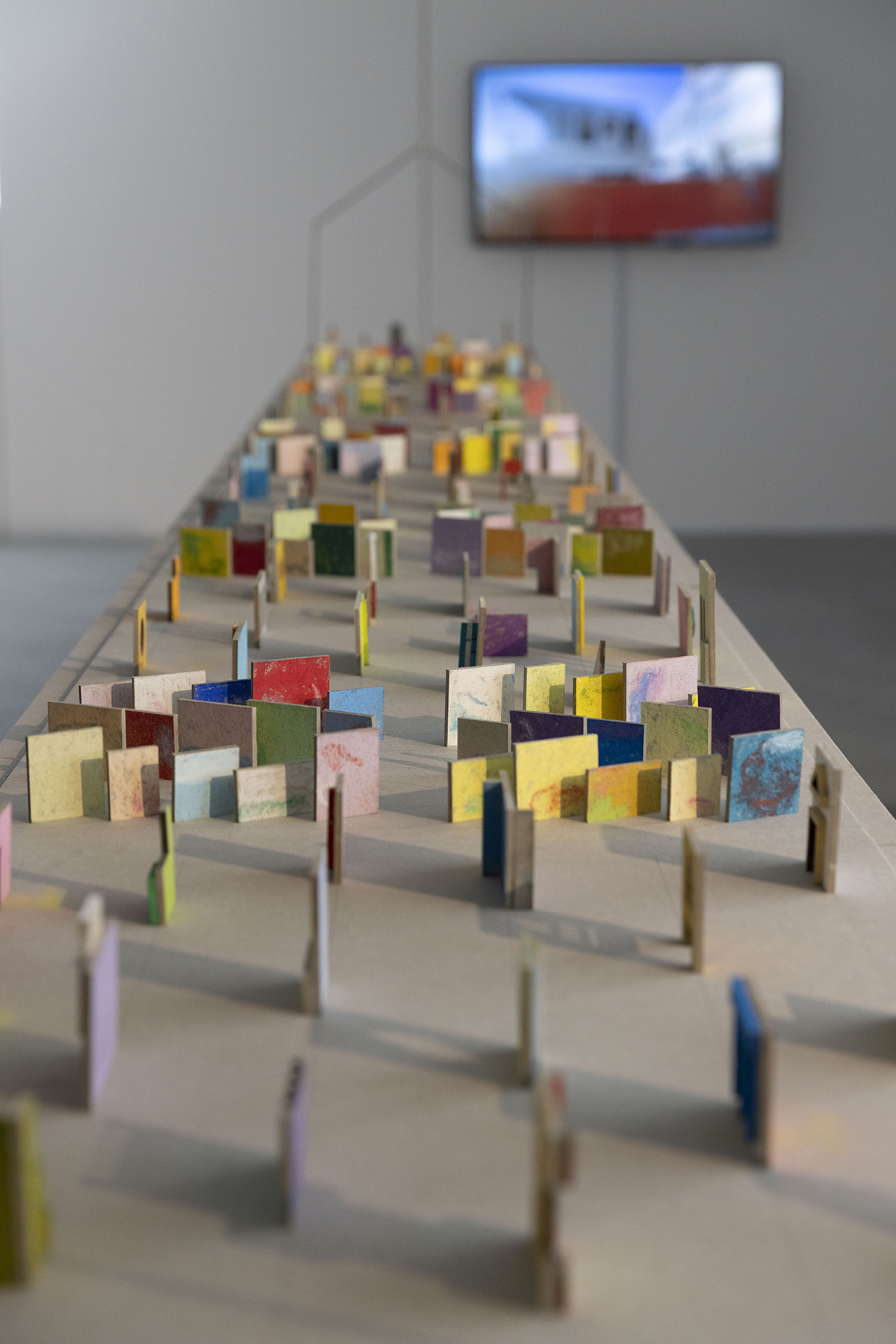

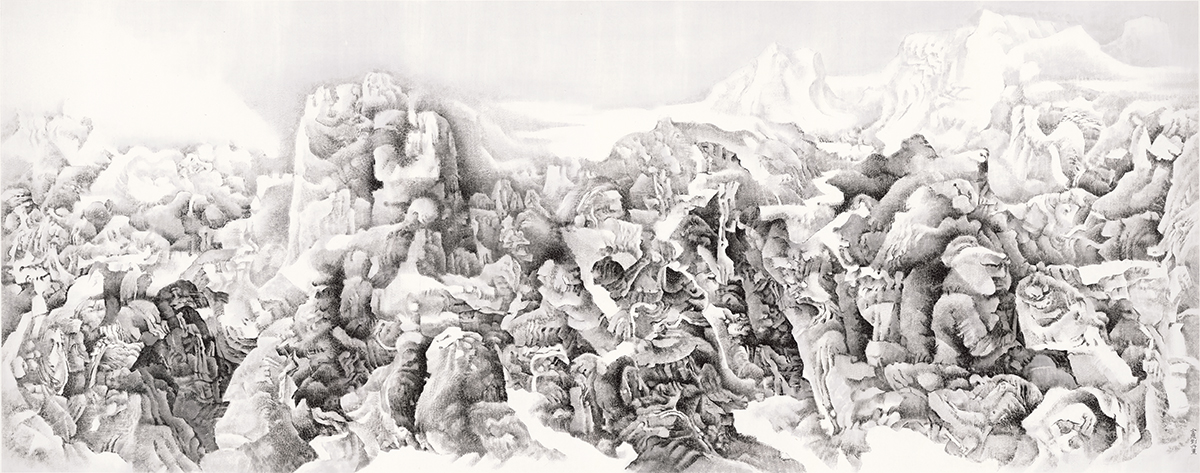

One example of Durjoy’s mission to raise awareness of such artists is the 10-year Majhi International Art Residency Program. ‘Majhi’ in Bengali means boatman or the leader or guide. He is the one, explains Durjoy, who steers people on the boat on a certain course. “My vision is to take artists from South Asia and the Global South to Europe every year to work with artists there so that they can exchange thoughts and ideas.” The first edition of the Majhi International Art Residency took place in Venice in 2019 and the 11 artists selected included Dilara Begum Jolly, Dhali Al-Mamoon, Rajaul Islam (Lovelu), Noor Ahmed Gelal, Uttam Kumar Karmaker, Kamruzzaman Shadhin, Umut Yasat, Chiara Tubia, Cosima Montavoci, Andrea Morucchio and David Dalla Venezia. They are from different regions of the world: six were born in Bangladesh, one is of mixed Turkish and German heritage, and four are Venetians. During their stay, the artists were invited to reflect upon the question: “Does life in these uncertain times of crisis and turmoil make art more interesting?” The question was a response to the title of Ralph Rugoff ’s 58th Venice Biennale that year, ‘May You Live in Interesting Times’. The first residency resulted in a dialogue of works that achieved exactly the aims of the foundation, with the artists choosing the title of the final exhibition.

The residency continued in Dhaka as part of the annual 15th Contemporary Art Day organised by the Association of the Italian Museums of Contemporary Art and supported by DBF. ‘The Scent of Time’ exhibition was hosted at Edge, The Foundation and featured work by the residency’s artists.

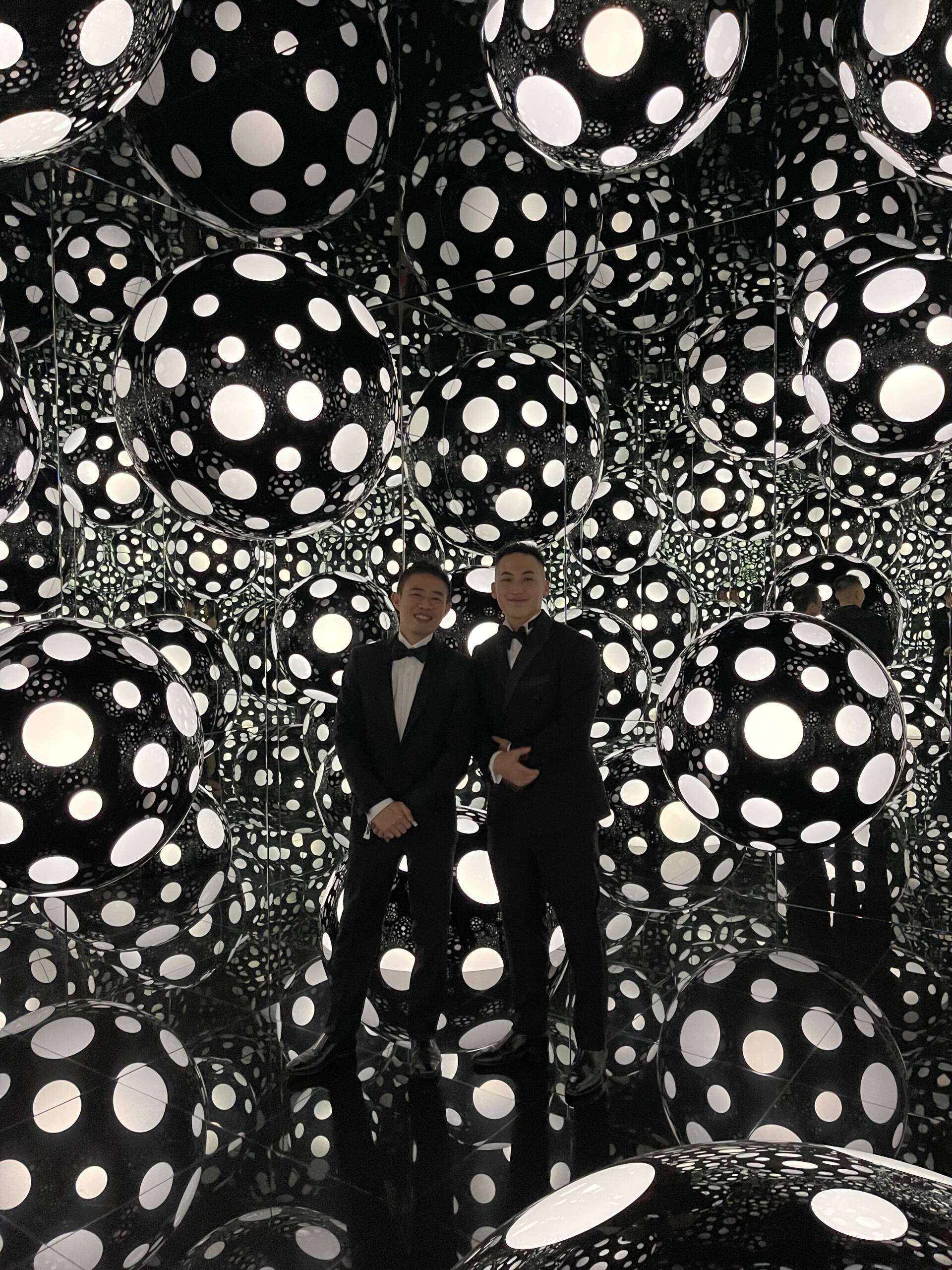

The Mahji International Art Residency in Venice, 2019, with artists David Dalla Venezia (top) and Umut Yasat. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Durjoy recently acquired a second work by Morucchio for his collection, a digital print on aluminium titled Merlyn. Durjoy says he was attracted to the artist’s work that drew attention to the dangerous effects of mass tourism in Venice, the subject of Morucchio’s project ‘Venezia Anno Zero’ documenting the serenity of the city during lockdown.

“Majhi, the boatman, travels from one destination to another – just like the artist going to the residency, he does not stop in one fixed place,” explains Durjoy. While 2020 posed numerous challenges, Durjoy made sure the Majhi residency continued. “When 2020 closed the world, we didn’t stop,” he says. “Because we already have a strong presence in Berlin, we decided to stage to residency there as part of Berlin Art Week.” The residencies, like Durjoy’s multifaceted vision, always involve numerous factors. For the Berlin exhibition, he invited a food and music collective to enliven the venue.

Read more: Gaggenau’s Jörg Neuner on embodying the traditional avant-garde

The foundation is now gearing up for its next location, Eindhoven in the Netherlands in October 2021. The theme is ‘Land, Water and Borders’. While Durjoy admits it is a challenging topic, it is ultimately one that reflects the present post-colonial struggles the world continues to experience. He says that, like the residency in Berlin, they will incorporate sound and acoustics into the residency that will take place during the Dutch Design Week. “It’s important that we make everything current,” he adds.

Durjoy’s cross-cultural efforts to elevate artists from South Asia are also apparent in his foundation’s recent partnership with the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, where international artists join a residency programme with an emphasis on experiment and critical engagement. “The objective of this partnership is to promote the exchange between artists from South Asia and the international artists’ network of the Rijksakademie and the strengthening of the position and visibility of artist from South Asia,” explains Susan Gloudemans, the Rijksakademie’s director of strategy and development. The first Fellowship is for Rajyashri Goody from India, who started her residency in September 2021. Rajyashri has been selected from 1,600 artists from 115 countries for one of the 23 residency positions available. The Fellowship covers the living expenses of the artist and is a direct way of contributing to the professional development and breakthrough of a promising artist. “The importance of DBF’s support of the Fellowship programme goes beyond the individual artist,” Gloudemans adds. “We know from experience that this line of support will increase the participation of other artists from the region in the Rijksakademie programme and that the local art scene in Bangladesh and South Asia will be able to benefit from the exchanges and collaborations that result from it.”

Durjoy Rahman with the artists and curators from the residency’s 2019 edition. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

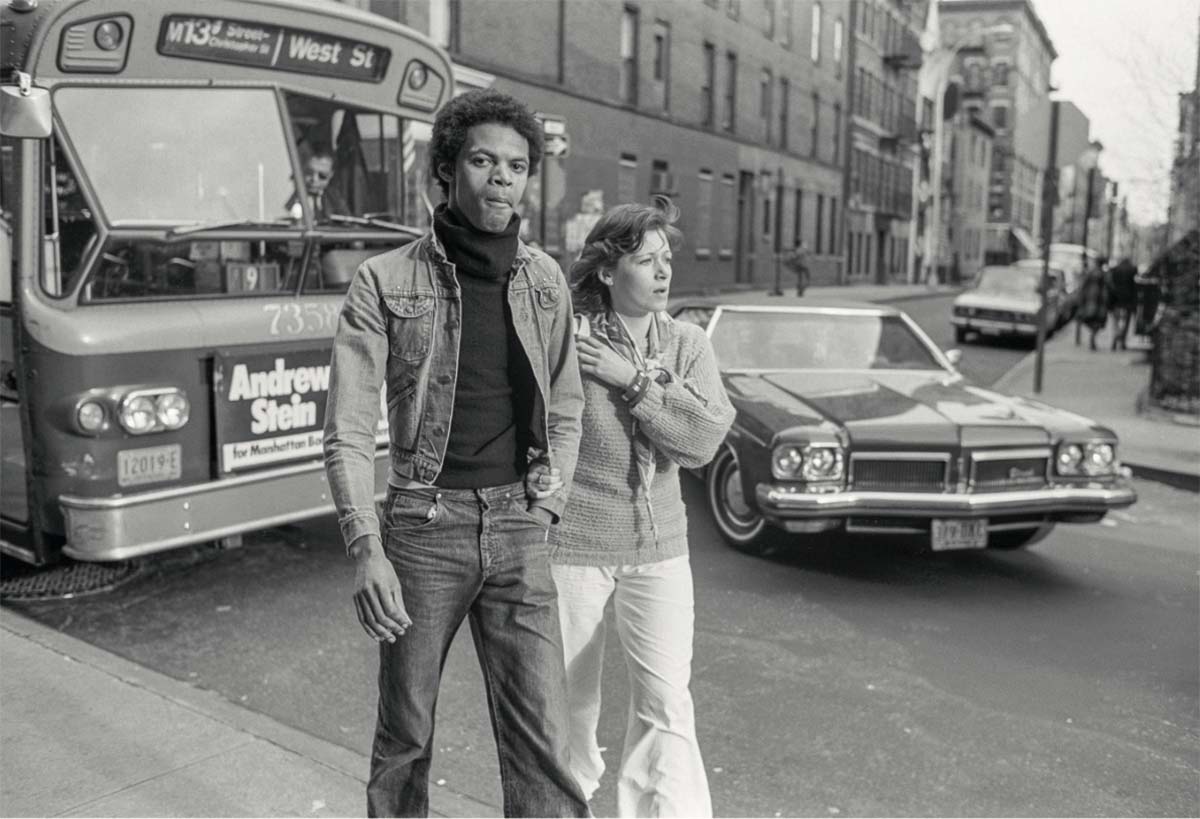

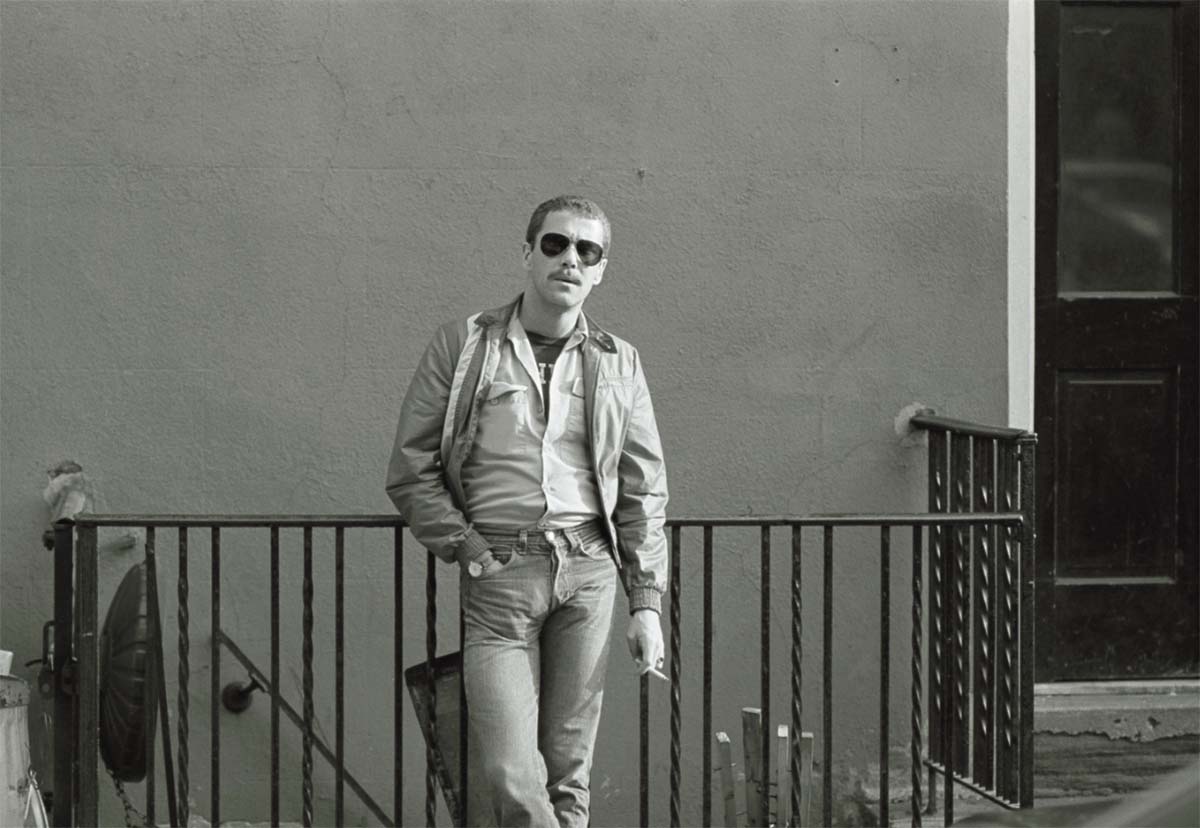

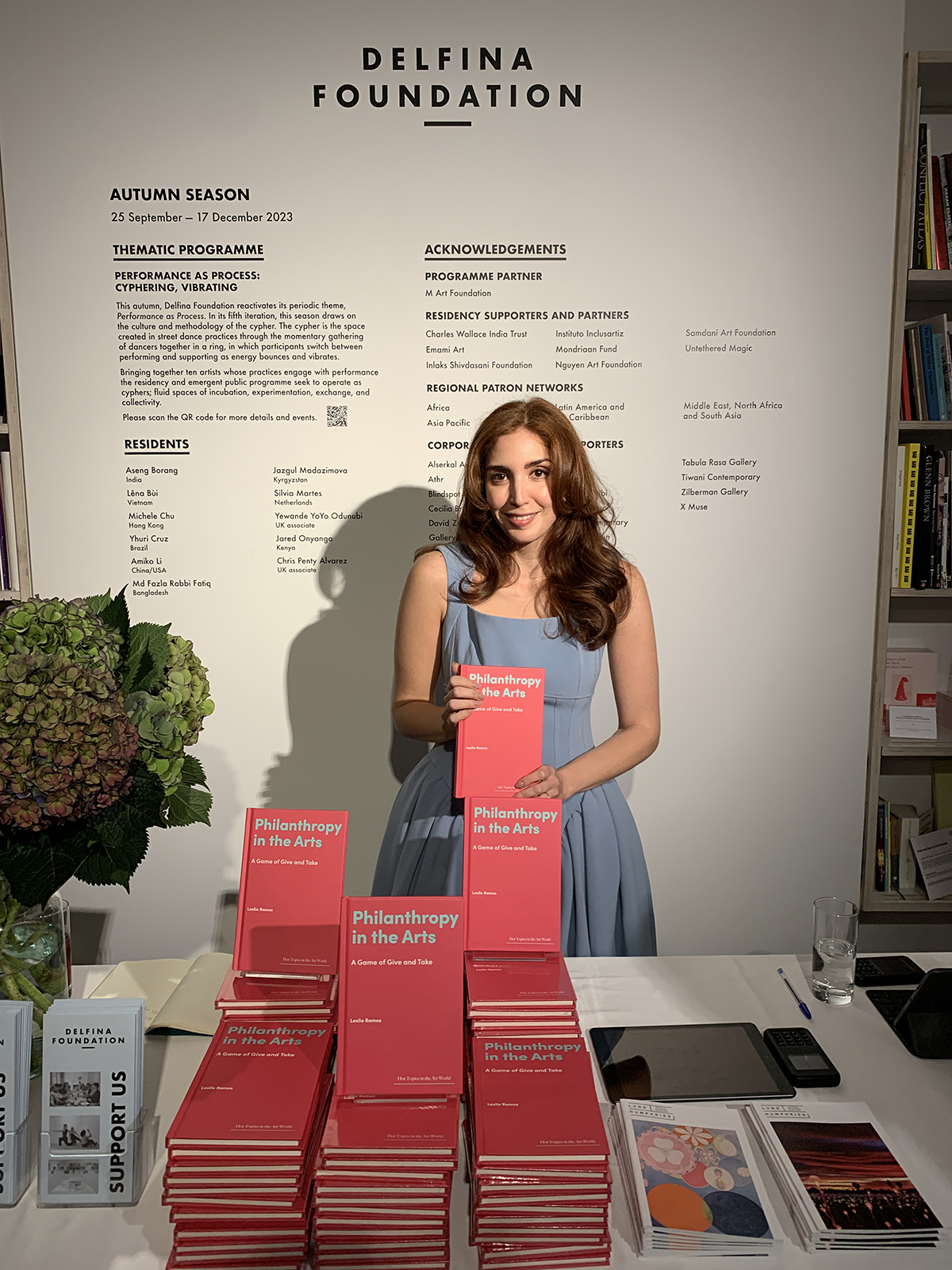

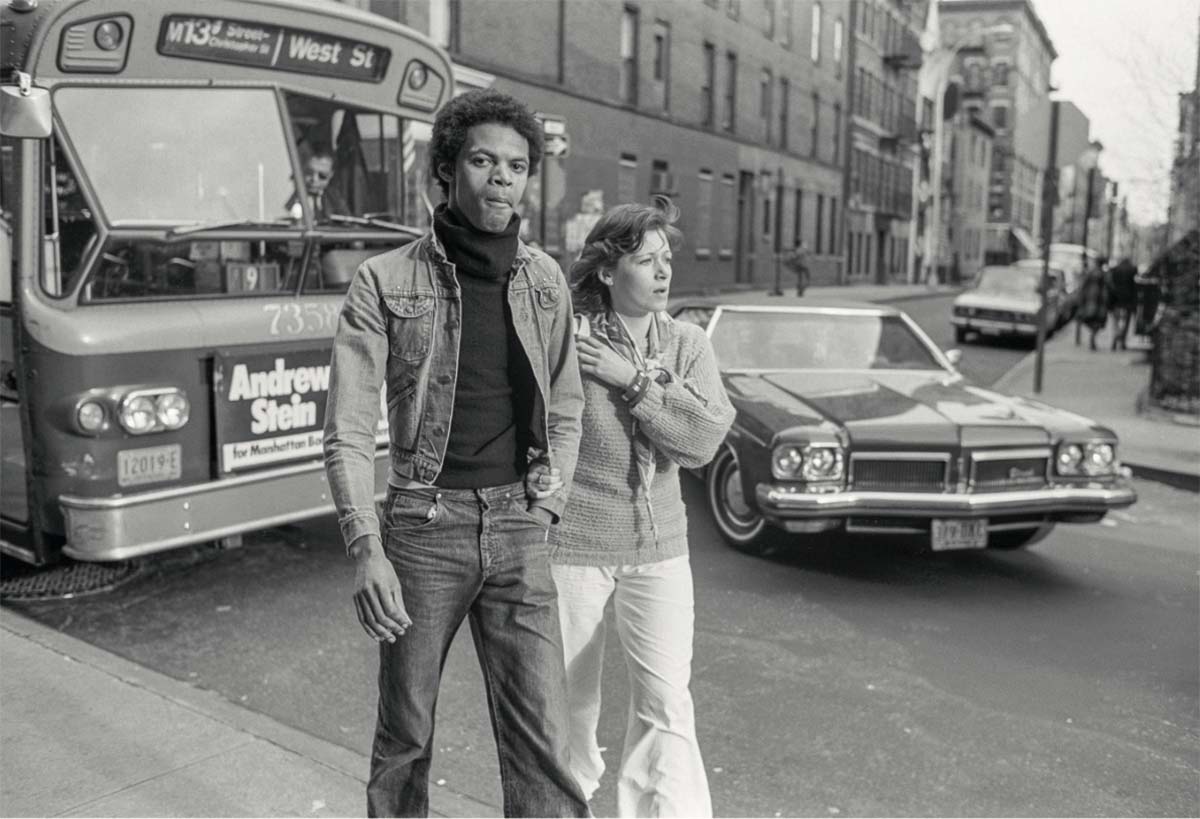

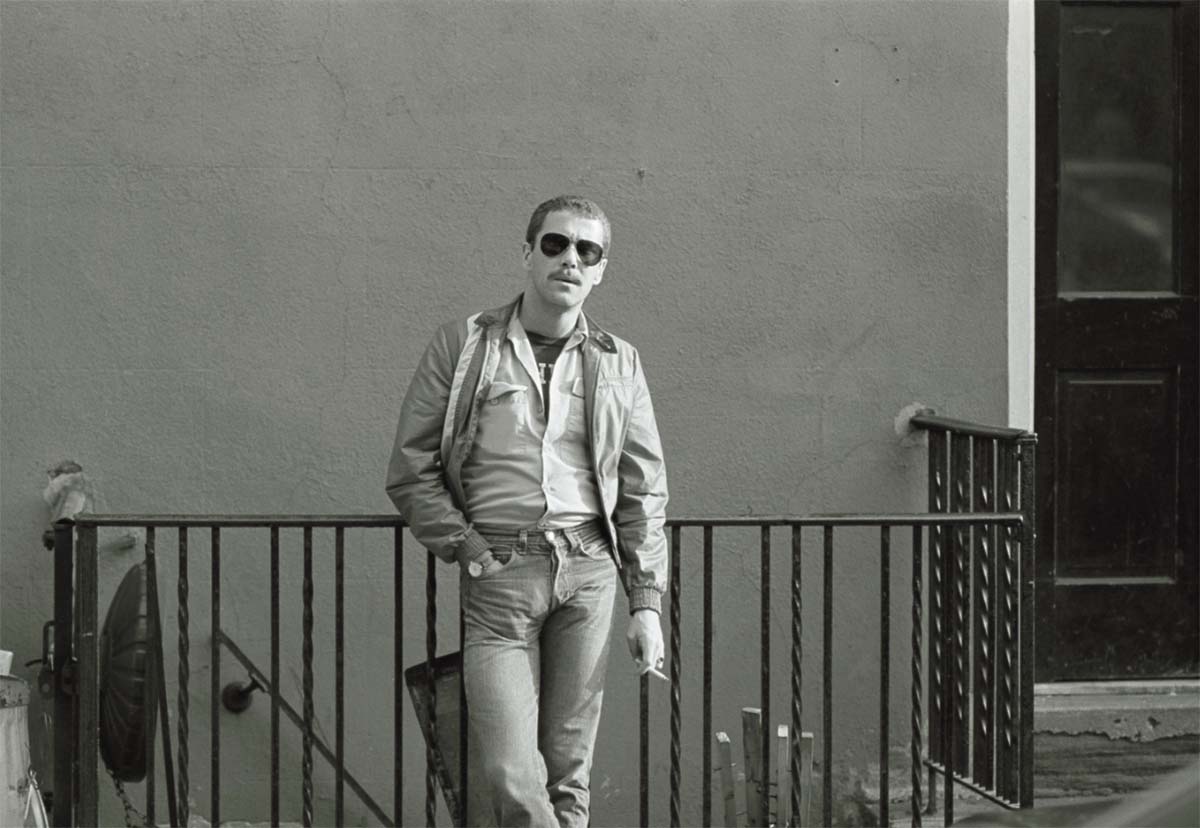

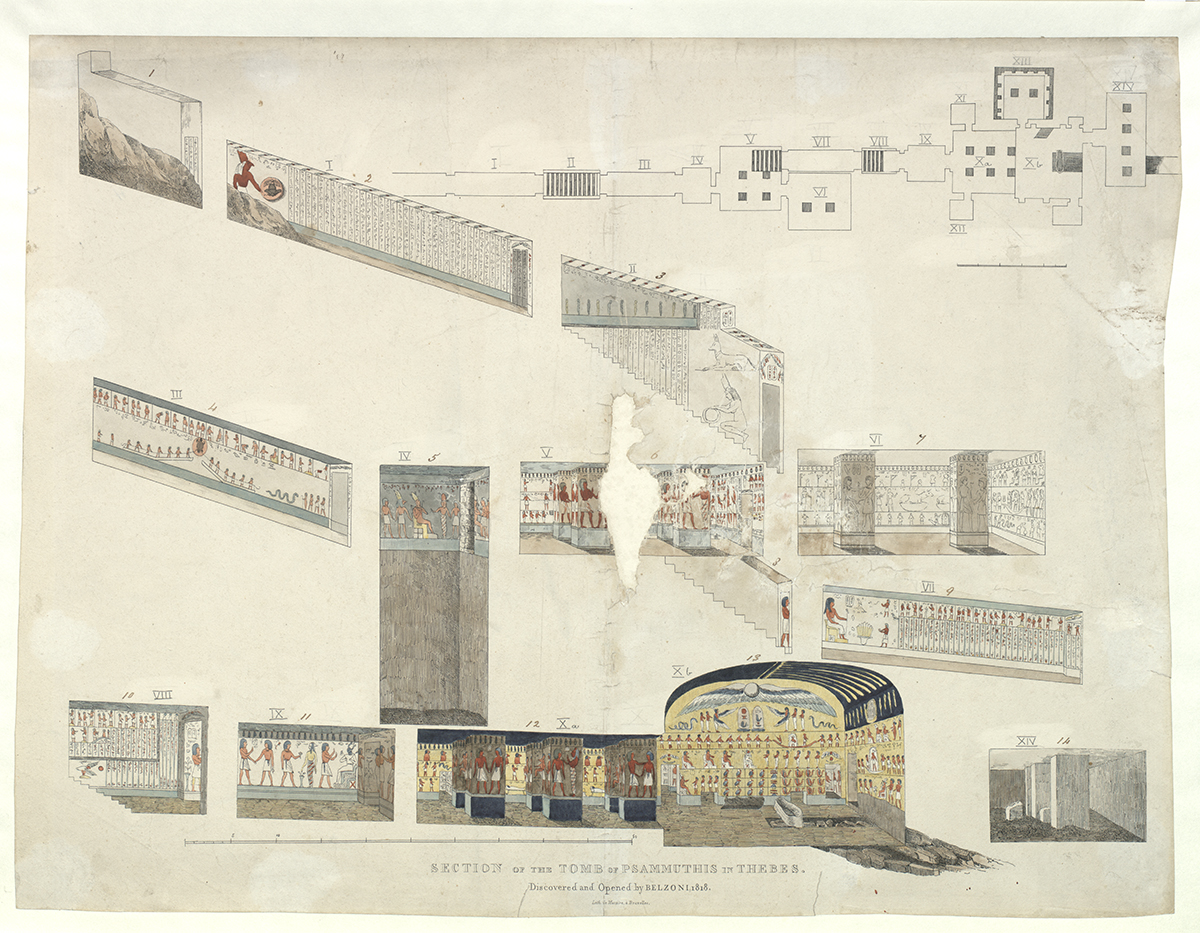

Durjoy’s passion and endless enthusiasm for his foundation’s mission is contagious. A silent artistic revolution seems to be taking place in Dhaka and Berlin, one that is urging artists and arts practitioners to become more open-minded in their approach and vision through artistic and creative dialogue. These are results, as Durjoy knows, that can only come about when people from various cultures and nations are brought together to speak, work and learn from each other. In March 2021, the DBF hosted ‘From Here to Eternity’, a one-day online symposium looking at topics such as gender, sexuality and race in relation to art and photography; the transnational consciousness in cities of the UK, North America and India; and artistic responses to social and political change. Along these same themes was DBF’s support for renowned Indian photographer Sunil Gupta’s show ‘From Here to Eternity: Sunil Gupta. A Retrospective’ at The Photographer’s Gallery (TPG) in London in 2020–21. “Given the scarcity of cultural organisations promoting the work of visual artists from the Global South, the Durjoy Foundation is filling an important vacuum within cultural relations,” says Francesca Pinto, the director of business development at TPG.

The North-South divide is a present reality reflecting centuries of colonialism, tensions and political feuds. If trauma is inter-generational, then to heal the resulting pain means looking at its origins, and Durjoy’s work through DBF attempts to make past wounds less painful through an understanding and recognition of the other through art. It starts, as he is demonstrating so passionately, by raising awareness about challenging socio-political and economic subjects. As he puts it: “When the headlines no longer carry these stories, then art can continue the narrative.”

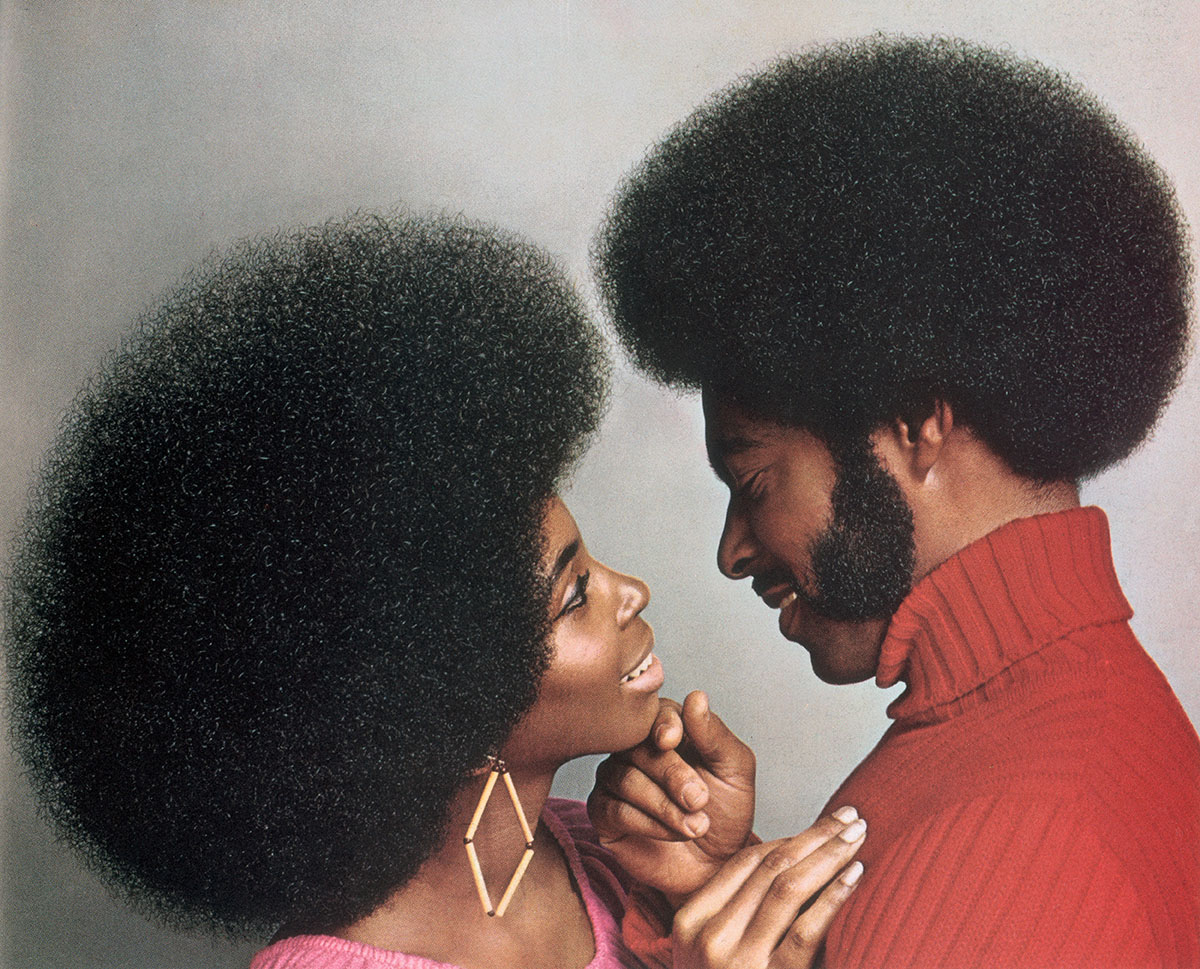

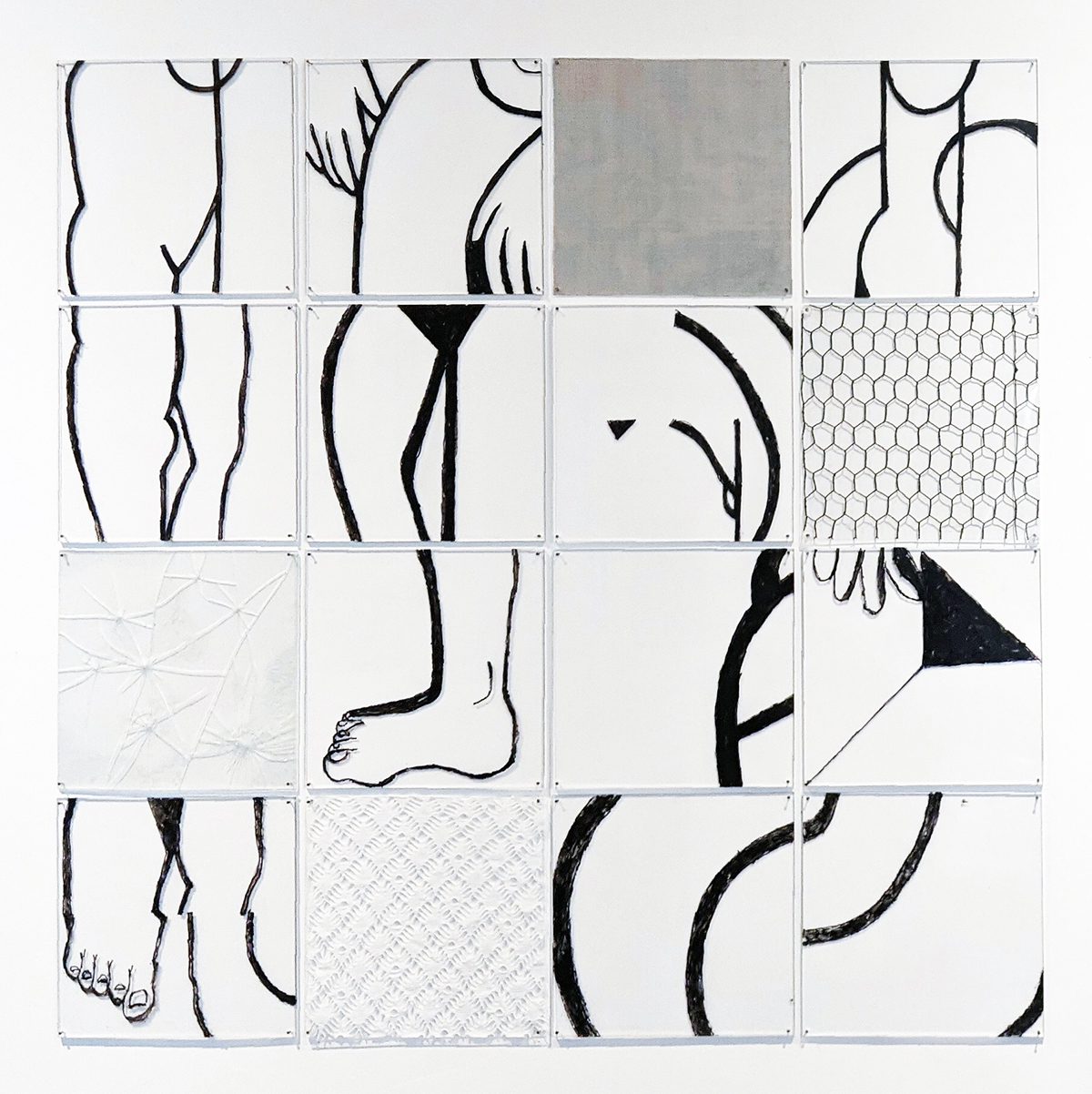

Images from Sunil Gupta’s series ‘Christopher Street’ (1976) from Durjoy Rahman’s collection. Images courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery and Vadehra Art Gallery. Copyright Sunil Gupta. All Rights Reserved, DACs 2021. Courtesy of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

How to define the Global South?

There is still much discussion over how to define the ‘the Global South’, a term coined in the late 1960s but being increasingly used today. The concept of the Global North and Global South (or North-South divide) describes a grouping of countries according to socio-economic and political characteristics. The Global South usually denotes lower-income countries, once referred to as Third World countries, while the Global North is often equated with developed or First World countries. However, this distinction can be misleading. Nations in the Gulf of Arabia, for example, are in the Global South but can be characterised as Global North countries. “During the Cold War we had the Third World model, which referred to the first world, second world and third world,” explains Ifkhtiar Dadi, a professor in the Department of the History of Art and Visual Studies at Cornell University. “Since the 1990s, the Global South has emerged as a working definition to look at the realities of these regions over the past 30 years since the end of the Cold War. I feel it is the most neutral and effective term today but the critique against it is that it evacuates the politics of an unequal world.”

As borders continue to be disputed despite an increasingly globalised world, the ideas of ‘home’ and ‘belonging’ continue to be questioned. Dr Devika Singh, a curator of International Art at Tate Modern who specialises in art from South Asia, illuminates the paradigm in the book Homelands: Art from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, published to accompany the exhibition of the same name at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, UK. “The notion of homeland belongs to the realm of the imagination and to seemingly distant, yet constantly revisited, pasts,” she writes.

“It also belongs to our present times of suffering and anxiety often spawned by national borders. The imposition and safeguarding of borders disrupt not only the long histories of human movements and exchanges, but also shared pasts, languages, and cultures. Displacement, whether forced exile or voluntary expatriation, and the notions of home and nation, therefore, appear intrinsically connected.”

Find out more: durjoybangladesh.org

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue.

Maryam Eisler: How wonderful that you have so seamlessly managed to connect your work around nature with a place of great natural beauty,

Maryam Eisler: How wonderful that you have so seamlessly managed to connect your work around nature with a place of great natural beauty,

JOHAN GRANVIK

JOHAN GRANVIK

KAREN O’MAHONY

KAREN O’MAHONY

2. Can you tell us your favourite story about one of the bags you’ve sourced?

2. Can you tell us your favourite story about one of the bags you’ve sourced?

The first watch in the series recalls long- past glory days with a brushed platinum case to echo the dashboards of classic Scuderia Ferrari models, as well as a leather strap and bright-yellow markers and hands to bring to mind old-fashioned speedometers. The model celebrating the here and now does so with a 3D carbon case and a strap made from Nomex, the fire-resistant material Ferrari drivers rely on to keep their suits from going up in flames.

The first watch in the series recalls long- past glory days with a brushed platinum case to echo the dashboards of classic Scuderia Ferrari models, as well as a leather strap and bright-yellow markers and hands to bring to mind old-fashioned speedometers. The model celebrating the here and now does so with a 3D carbon case and a strap made from Nomex, the fire-resistant material Ferrari drivers rely on to keep their suits from going up in flames.

Recent Comments