Durjoy Rahman is an art patron and collector, and the founder of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

Art collector and patron Durjoy Rahman founded the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation in 2018 to promote South Asian art and artists to global audiences by hosting exhibitions, commissioning new works and facilitating cross-cultural residencies. As part of our ongoing philanthropy series, he discusses the business of art philanthropy and why artistic narratives play an essential role in documenting history

LUX: How does giving fit with your beliefs?

Durjoy Rahman: Giving has been engrained in me since childhood. My parents instilled the importance of money management by giving me an allowance from a very early age. I was always told to save, use and give from that amount. It’s something I teach my children. The gift of knowledge is often held in high esteem in Asian culture more so over monetary ones. Due to limited availability of wealth to majority of the people and the long history of colonialism, the patronage of the arts and culture was very scarce and I wanted to contribute in a meaningful way. I feel privileged to be able to promote artistic endeavours from southeast Asia.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: Why were you compelled to collect art as opposed to another valuable asset type?

Durjoy Rahman: I started collecting by chance not by a scheduled plan. We received a beautiful painting as a wedding present from a prominent artist. I wanted a few more paintings for my walls, so I started to visit galleries to find things I liked. Then I started reading more about the artists whose works spoke to me. I collected pieces that were notable and told stories about their artistic journey. Most pieces were passion buys just because I loved them. The inherent value of art lies in the pleasure of acquiring it and holding on to it. If one goes in with the mindset of building assets, the fun of collecting evaporates in entirely. Of course, the collection is valuable not because of its market value but because many were done by artists who introduced new techniques in Bangladesh and played an integral part of our art history. Many works were destroyed due to lack of preservation so not many notable works remain.

LUX: What triggered your decision to advocate for South East Asian artists?

Durjoy Rahman: South Asia has a rich cultural heritage. Art, music, and dance are a part of our daily life, but because of the long history of colonialism, artistic patronage was scarce. After independence, more and more art institutes were established and art movements were started. Now, the world is becoming more connected and the traditional hubs of art in Europe are also encouraging more diversity. This has made the global art scene very interesting and not limited to only European schools. The South Asian art scene is becoming more established with the growing number of art events and institutions, but still the artists need a lot of support to be able to establish themselves internationally. Patronage is essential for art to thrive and survive. Our artists are very talented and I hope that the individual like myself can contribute to introducing these artists to an international audience.

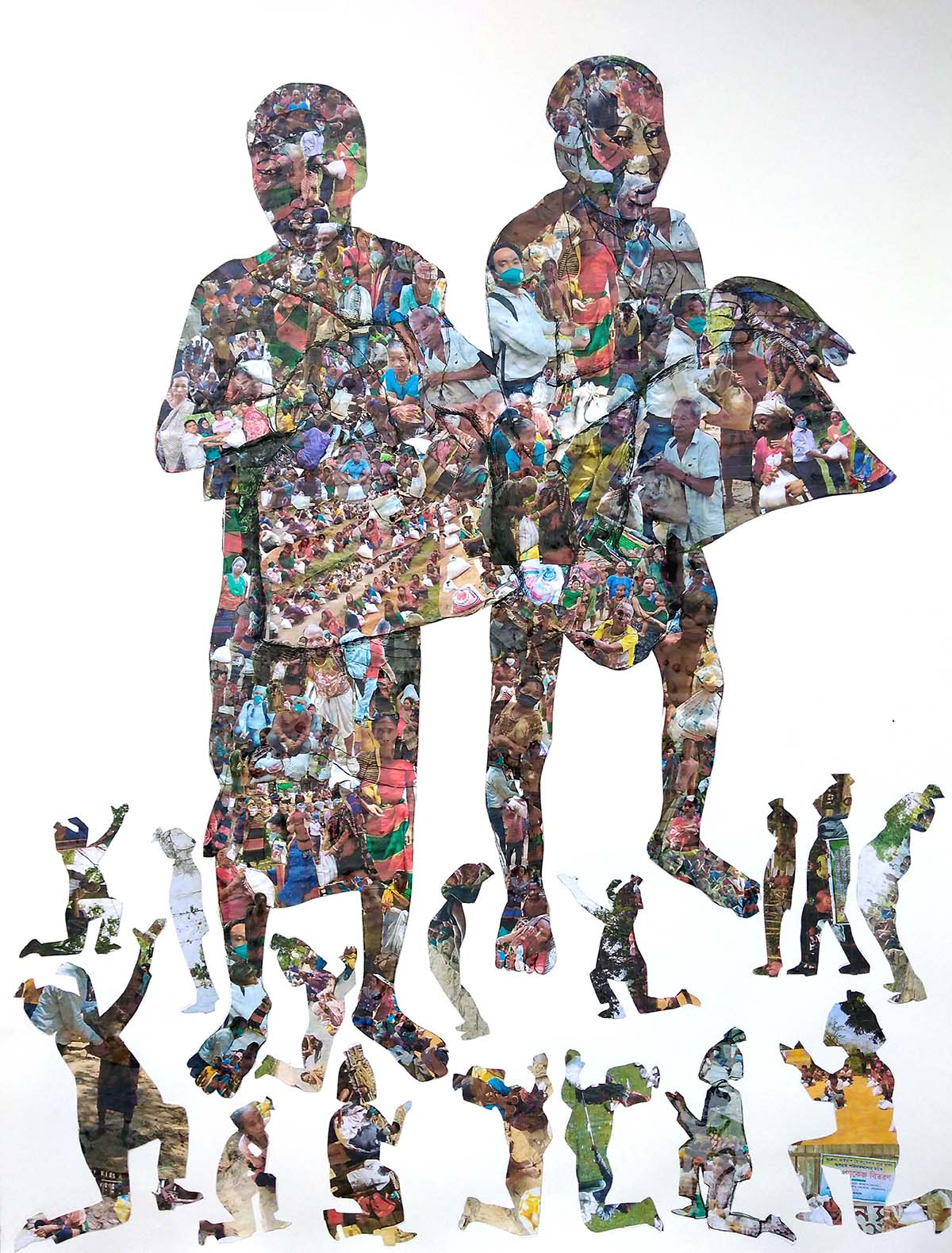

Joydeb Roaja, The Right to Relief, 2020 – one of the artworks included in Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation’s 2020 online exhibition Future of Hope

LUX: Western narrative discourse about South East Asia is dominated by tragedy, conflict, schism, floods, famine, genocide. What is the relevance of art in crisis?

Durjoy Rahman: South Asia was under colonial domination for centuries. The postcolonial period has been plagued by border and religious conflicts. Conflict, famine, tragedy has happened in every country in the world; the Great Depression in the United States, Europe after World War I and II. Every country has experienced suffering but the Western narrative about our region was most remembered because of globally televised news that emerged in the 60s and 70s that established these stereotypes for South Asia. All crises always inspired the creative community. It’s their narrative that makes us understand human suffering better. Otherwise, it’s just historical information. The birth of Bangladesh in the 70s was followed by a famine. Many artists depicted horror with their artworks. I think these artworks depicted suffering for generations to come and understand what the country went through. Only humans can create beautiful things out of a painful experience. The narrative creates history.

Read more: Jewellery designer Tessa Packard on charity & creative thinking

LUX: Where will the voice of truth and art tell the history in these dark times in Myanmar?

Durjoy Rahman: It is said the history is often written by victors but it is little relevant now due to global access of information to everyone. Every narrative is available and it is up to reader to draw their own conclusions. Documentation and witnesses about Rohingya plight made the world change their views. The sufferings are established fact result from the autocratic activity by the ruling regime. The quarter that caused these past miseries have solidify their position with the new situation that recently unfolded in Myanmar.

Artworks and tapestries created by Rohingya women and children depicting the horrors they endured will always be a part of history; they have cast aside the “official” narrative .

Mong Mong Sho, Songs Of Covid 19, 2020 from the Future of Hope exhibition

LUX: Why did you headquarter DB Foundation in Dhaka and Berlin?

Durjoy Rahman: Berlin and Dhaka are both thriving art cities filled with many talented artists. DB Foundation aims to be a conduit for art and artists across Europe and South Asia. Berlin is an international city for art and design and a perfect place to build greater awareness for South Asian artists on the global stage while Dhaka remains DBF’s epic centre for activity.

LUX: Your focus is ‘to promote art from South East Asia and beyond in a critical, international art context.’ Which countries particularly?

Durjoy Rahman: Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

LUX: Are there examples from this rich art heritage you are excited to have introduced to the West?

Durjoy Rahman: Bengal has thousands of years of heritage in art and craft. Textiles were one of the wonders from this region and played a dominant role in our glorious past. Historically, the intricate weaving in Muslin fabric from Bengal received an appreciation from the West and also became a sign of superior craftsmanship in many European royal courts.

Through the DBF’s outreach program and artist residency program, we aim to show the world once again the skill and creativity of Bengal. I have the privilege of donating a work by Mithu Sen from West Bengal, India to the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany. Her work is based on a collection of memorabilia that people normally collect as souvenirs. It was a great accomplishment to help bring Mithu’s work to the western audience according to the Museum press release the first work of a female contemporary artist collected by a major public institution in Germany.

Currently, we are working on a project that will tell the story of displaced elephants due to the Rohinga crisis where the artist used sustainable material like bamboo and quilt making skills to tell a story about this plight of humans and animals caused by conflict. The work will be displayed internationally with the support and initiative from DBF.

LUX: Your archive of artists, past and present is acclaimed and you mentor emerging artists. What was the game-changer for DB Foundation in a critical sense?

Durjoy Rahman: The real challenge for us has been to find a niche in the global art events and to make a meaningful contribution to the artist community. We adopted the model of a residency program centred around an idea or a burning issue. Artists from different parts of the world interpret the central theme. For two weeks the artists live and work together. For artists in southeast Asia, it’s a unique opportunity. For artists from Europe, this is also an experience to work with the brilliant artists from Asia and understand their perspective. So I would say our Majhi Art Residency program is a game-changer for DBF foundation which we have been hosting since 2019 and plan to continue for the next ten years.

Sujan Chowdhury, Wings of Hope, 2020 from the Future of Hope exhibition

LUX: How did the pandemic affect upcoming exhibitions, commissions and residencies?

Durjoy Rahman: We have ventured alternate art space to exhibit art on a limited scale while major public exhibition spaces were closed. We continued our International Art Residency in Berlin during Berlin Art Week 2020 despite pandemic and to maintain consistency of the continuation of our supported projects internationally. However, the pandemic has really brought forward the need to use technology in every aspect of our lives and the focus has shifted to connecting virtually. We too are focusing on remote initiatives and found the many ways one can connect to a greater audience. We still tried to engage artists and marginalised artisans during the pandemic while observing safety protocols. Last year, at the peak of the pandemic, many craftsmen and their families in Bangladesh were greatly affected due to the economic downturn and low tourism activity. We created an initiative to support traditional craftsmen and their families by offering practical and financial support so that they can continue the creative process.

Read more: Alia Al-Senussi on art as a catalyst for change

LUX: Circularity could be said to future-proof giving. How can business support art philanthropy at the level of helping people help themselves as opposed to funding them top down?

Durjoy Rahman: The business of art philanthropy has been historically top-down going back to how art and crafts were supported by royal and affluent patrons in the Europe, Americas and Asia. I think that to create a more sustainable and self-sufficient model, the public needs to get involved and be motivated. While I think that the top-down approach will always be a critical part of art philanthropy, businesses can create public demand by creating programs for the public (especially virtual events) meant to keep the public engaged and inspired. As long as this demand exists and businesses are meeting it, they will become partially self-sustained in funding channels.

LUX: 2020 was Covid-dominated, hopeless, until the point of vaccines’ licensing, as will be seen when lexicographers list the vocabulary we used most. What can art philanthropy offer in a wider sense to humankind?

Durjoy Rahman: The Covid pandemic has really focused the public on the importance of one’s mental health. Creativity, art, and culture are the ultimate mind healers, and art philanthropy supports that. Being a cultural foundation DBF were probably the first organisation in Bangladesh got involved with front line workers to equip them for better safety and serve people more confidently.

Here & above: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation launched its philanthropic project “Bhumi” in 2020 to support rural creative communities in Bangladesh. Courtesy Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation and Gidree Bawlee Foundation of Art

LUX: Your passion to connect extends to activism through your support of satirists and the rights of minorities. What do you feel was particularly relevant to defend in 2020?

Durjoy Rahman: Migration, displacement, and supporting minorities. We focused our activities with minorities in 2020 through one of our major initiatives “Bhumi”, where we worked with artists and craftsmen from a marginalised ethnic group. We are currently working with Rohingya refugees and the environmental consequences of this mass migration. We are trying to build awareness among the international community about the plight of this ethnic group and its impact on the fragile hills of our border and the already dwindling elephant herd which inhabit that area.

LUX: Where has DB Foundation facilitated public discourse and created the climate for political change?

Durjoy Rahman: Diversity has been at the centre of the creative field, especially now. We have done several initiatives across Europe and Asia aimed towards actively facilitating our activity in the arts and culture from South Asia. Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation wants to bring representation to these artists, give them the recognition they deserve, and bring their voices into the art conversation, so they are heard. Our initiative “Future of Hope” has also highlighted a key word “hope” during the early break of pandemic. Now, “hope” has become a global slogan.

LUX: What one piece of advice should an art philanthropist share with the next generation?

Durjoy Rahman: Be generous when thinking of art and culture – a small contribution can make a significant impact on the art and artist.

Find out more: durjoybangladesh.org