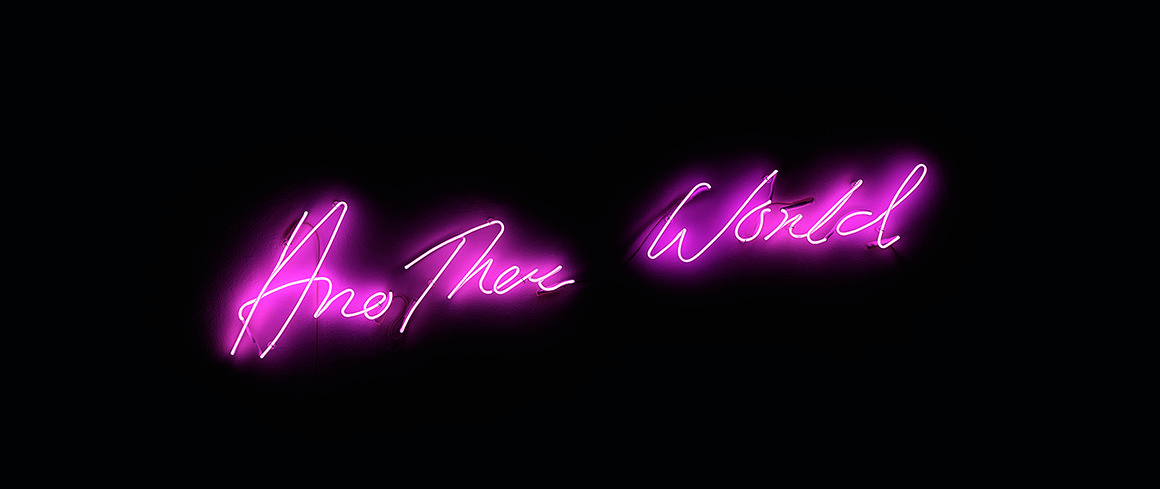

‘Another World’, Tracey Emin

Artist Tracey Emin and Deutsche Bank are marking 100 years of women’s suffrage with a show of work by female artists from the bank’s collection at Frieze London and Frieze Masters, as well as a secret postcard sale for women’s charities. Anny Shaw reports from the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounges

Tracey Emin. Image by Richard Young

To mark this year’s centenary of voting rights for women in the UK and Germany (and the fact there are still places in the world where women can’t or find it difficult to vote), the British artist Tracey Emin and her studio have curated an exhibition of around 60 works by female artists drawn from the Deutsche Bank Collection. Over the course of 35 years, the firm has accrued one of the world’s largest collections of works on paper.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

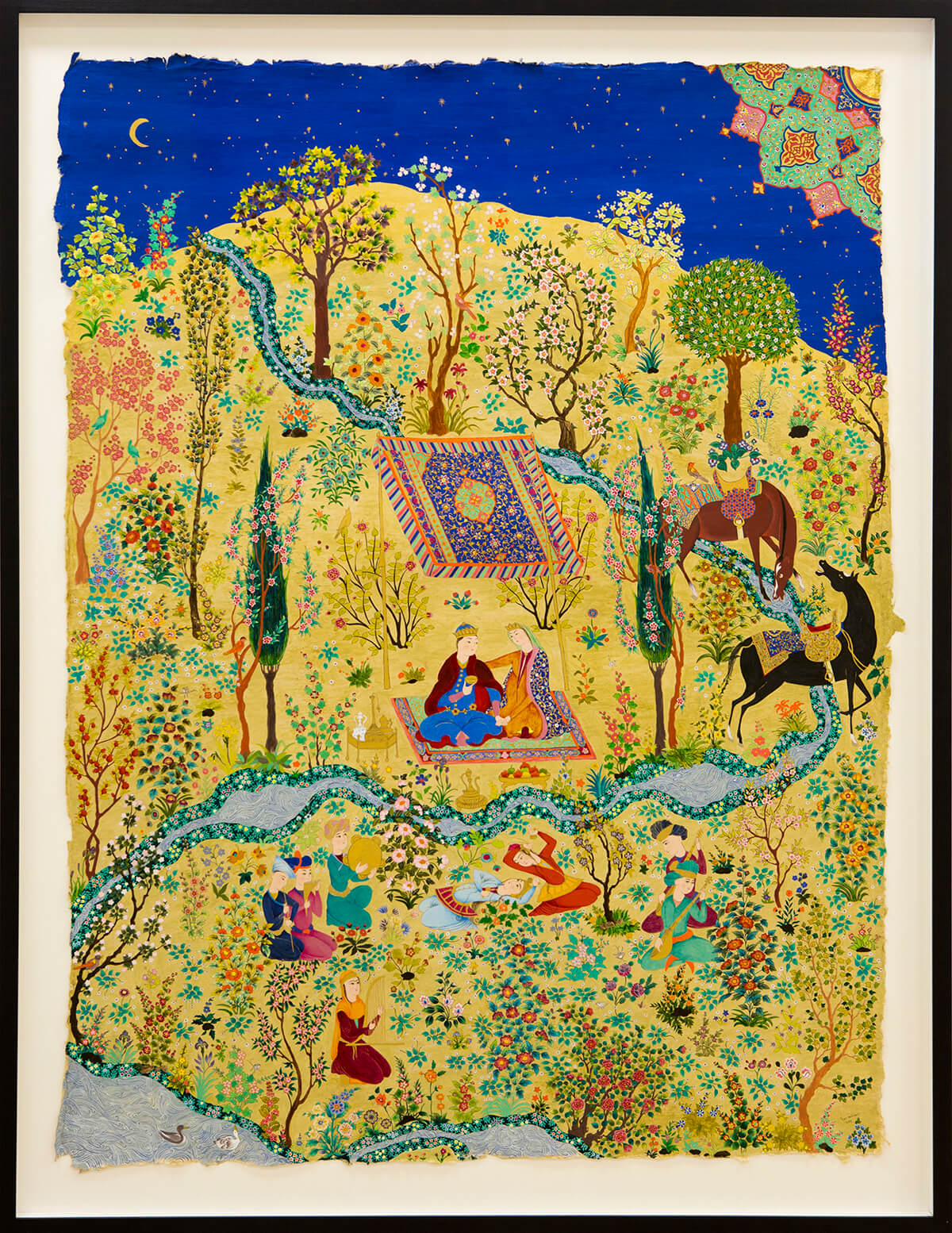

Entitled ‘Another World’, the exhibition spans both Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounges in Frieze Masters and Frieze London, featuring 34 artists working from the late 19th century to the present day. Emin’s selection includes titans such as Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), whose depictions of women and the working class countered the dominant male rhetoric of the time, and Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010), whom Emin admired greatly and collaborated with shortly before the French-born American artist died.

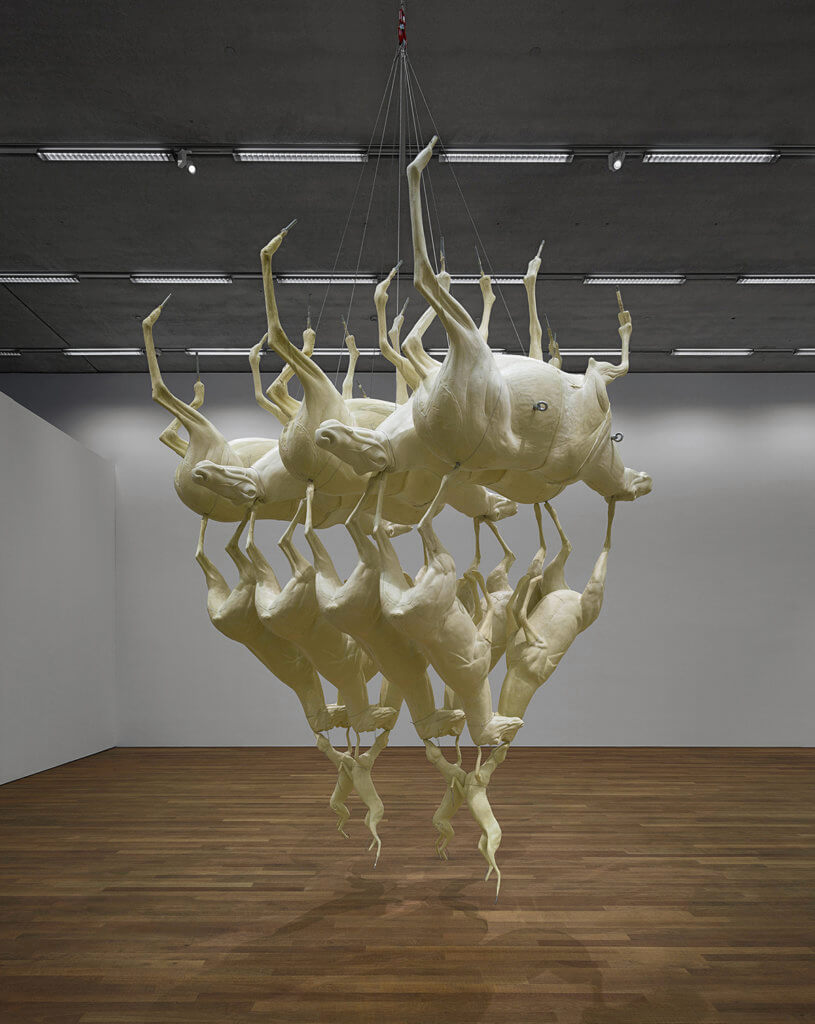

‘10am is when you come to me’ (2006) by Louise Bourgeois

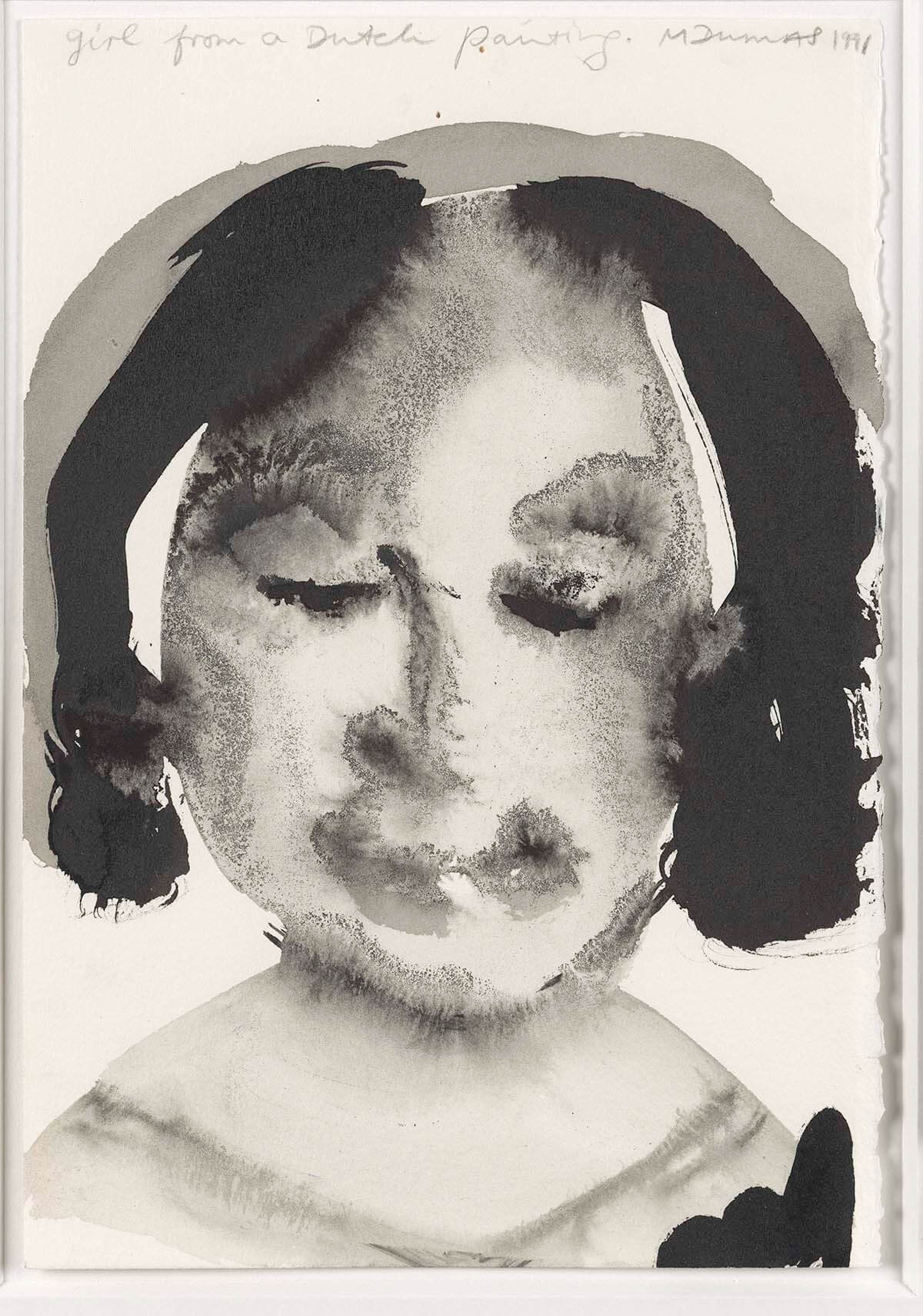

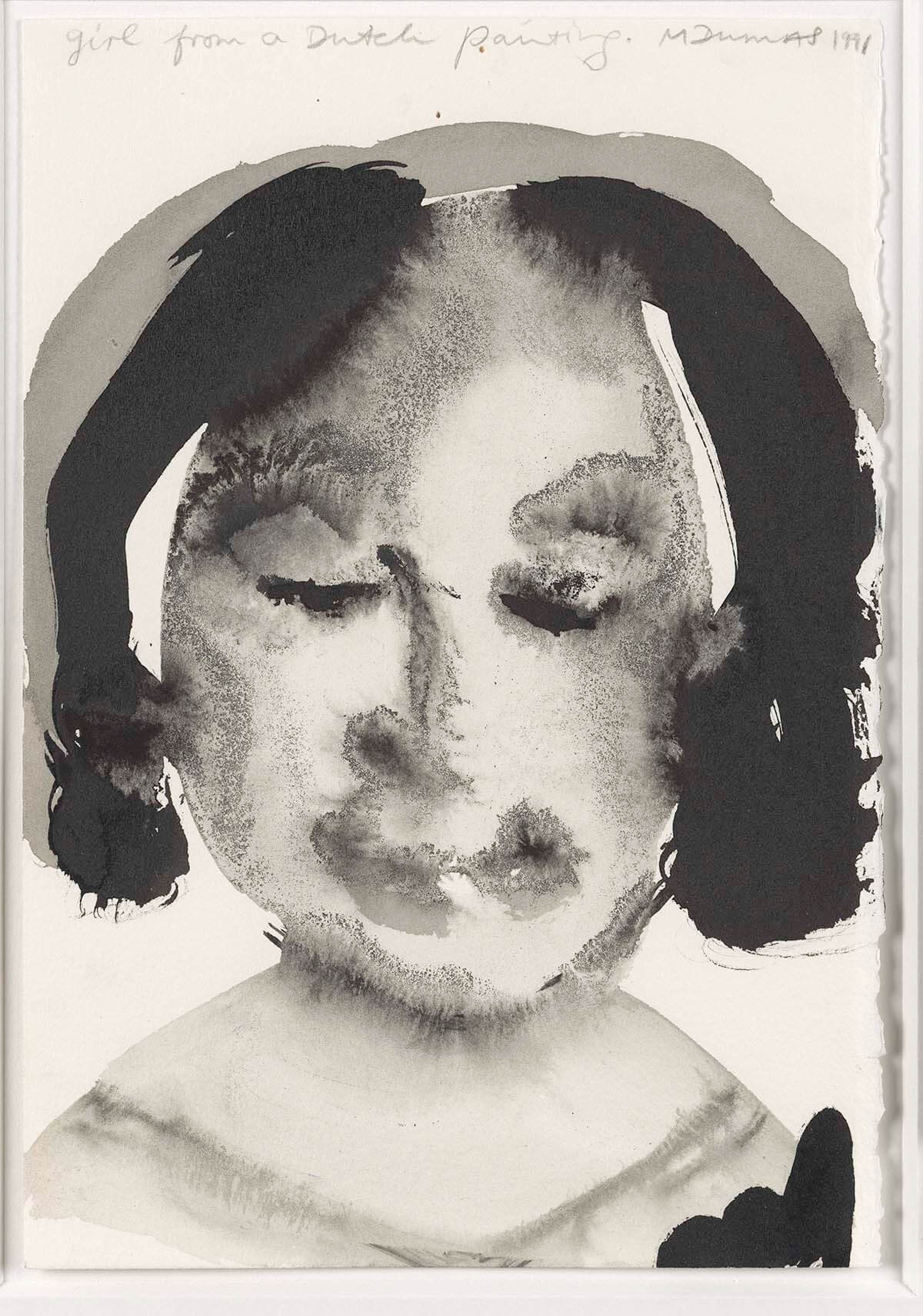

For the show, Emin has chosen Bourgeois’s 10am is when you come to me (2006), a work with 20 etchings including depictions of the hands of the artist and those of her assistant Jerry Gorovoy, painted with watercolor and gouache in various shades of red and pink. Contemporary artists featured in Emin’s selection include Maggi Hambling (b. 1945), whose 1993 aquatint of a heron “appears somewhat comical”, in Hambling’s words, and Marlene Dumas (b. 1953), whose work entitled Girl from a Dutch Painting (1991) represents a state of mind rather than being a portrait of a particular person.

A Show for Everyone

Although the show is dedicated to women (Emin and her studio reviewed all of the 670 female artists in the collection), Emin says she wants the theme “to relate to everybody”. The title could refer to a liminal or dream-like state, she points out. “Another world can be the twilight time when we are half asleep and half awake. Or literally another world, another universe, the animal kingdom, or for me personally, another world represents the afterlife,” Emin says. The artist has created a new neon work, Another World, especially for the show.

“We always look to provide a stimulating and relaxing environment for our guests in our VIP lounges, whether they want to take in our exclusive exhibitions or simply take a break during their visit,” says Nicola West, Global Head of Events, Partnerships & Sponsorships at Deutsche Bank Wealth Management. “This year, Tracey and her team have created something truly spectacular.”

Käthe Kollwitz’s charcoal drawing ‘Frau, auf einer Bank sitzend’ (Woman, sitting on a bench) (1905)

A quarter of the 2,694 artists in the Deutsche Bank Collection are women – higher than the 4% at the National Gallery of Scotland and 20% at the Whitworth in Manchester, though less than the 35% at Tate Modern. However, Mary Findlay, International Curator in the Bank’s Art, Culture & Sports division, acknowledges there is still work to be done. “We are always looking to buy more works by women,” she says. “Diversity and promoting women is something that Deutsche Bank is vocal about. This exhibition is a good way to continue that conversation.”

With the advent of the #MeToo movement and the centenary of women’s suffrage, the art world certainly appears to be changing. So what advice would Emin give to young female artists trying to forge a career today? “Use really good contraceptives,” she quips. “Don’t sleep with gallerists or anybody who could enhance your career. Try to be logical in all your arguments and if that doesn’t work scream the house down. Work every hour God sends.” But most important of all? “Do not compare yourself to anybody.”

‘Another World’ Postcard Project and Sale

Inspired by the annual secret postcard sale held by the Royal College of Art (where Emin studied) and by historical suffragette postcards, which were produced by campaigners for women’s rights as well as by those who opposed them, Emin has approached women artists in the Deutsche Bank Collection and asked them to contribute unique postcard works to the charity exhibition and sale. The result is in excess of 800 works. The project is in aid of organizations, yet to be chosen, that support vulnerable women in London and in Margate, where Emin grew up and now has a studio.

The postcards, priced at £200 each, will be sold anonymously, with around three-quarters on view in the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounge and a quarter available online. “What’s really interesting about selling works anonymously is that suddenly the name of the artist, and all that entails, isn’t important. You’re using your eye and your intuition to respond to what you see,” says Findlay. “That reflects the ethos of the Deutsche Bank Collection – we’re not about big names. Supporting creativity is at the heart of what we do.”

The long-term aim, Findlay continues, is to “create a legacy, and to do something concrete to actually help women who are the victims of abuse and change things for the future.” She expects the financial benefit of the project to continue into next year and beyond for the selected charities. “We have set up the Tracey Emin and Deutsche Bank Centenary Fund, which, with the large number of unique artworks we have to sell, will become a multi-year legacy,” she says.

‘Girl from a Dutch Painting’ (1991) by Marlene Dumas

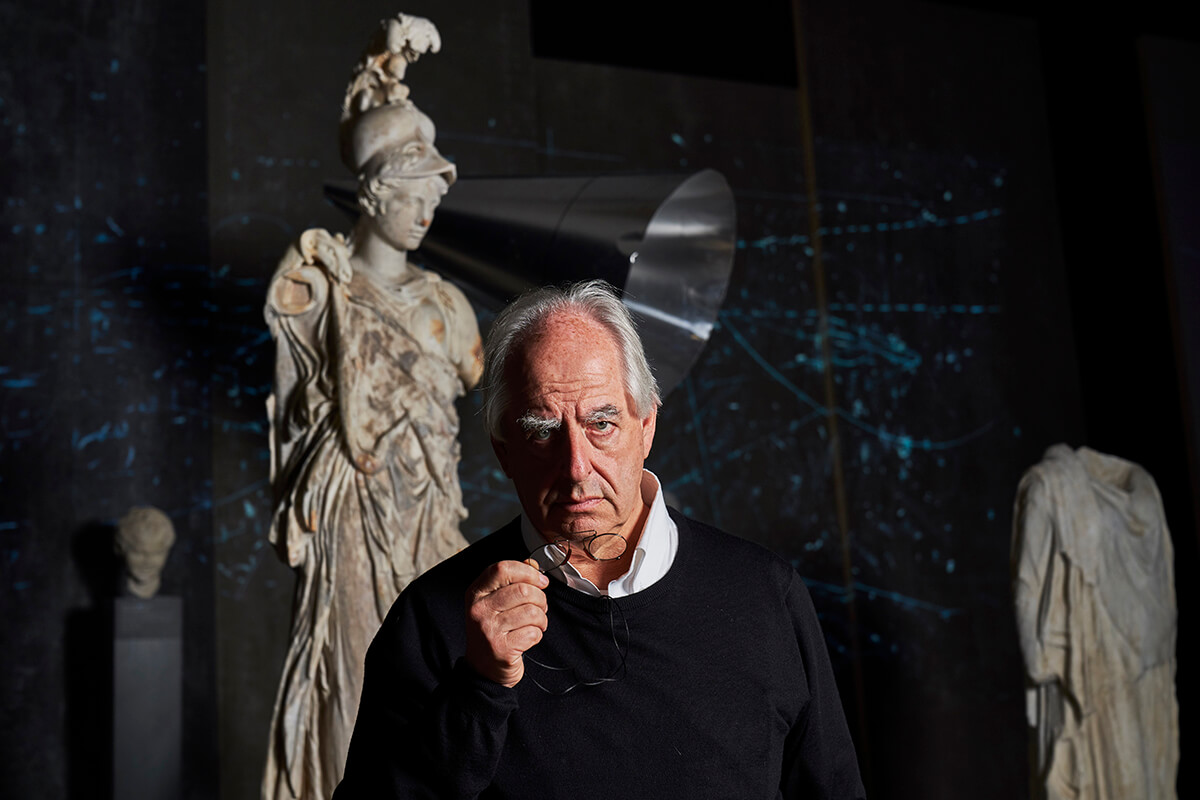

Maggi Hambling

The Suffolk-born painter and sculptor Maggi Hambling, chosen by the campaigners Mary on the Green to create a public sculpture in London to celebrate the feminist writer and thinker Mary Wollstonecraft, was quick to respond when Emin wrote asking for the women artists represented in the collection to submit postcards for charity. “Almost every day a case of domestic abuse is revealed. It takes a lot of bravery to come forward and talk about it,” she says. “If the sale of these postcards helps those who help the victims of abuse, then it’s a great idea.” Hambling says she opted to paint something “rather jolly”. She adds: “I haven’t tried to paint victims. I hope I have done something quite joyous.”

Hambling has sent in postcards to RCA Secret, the Royal College of Art’s annual fundraising secret postcard exhibition, every year since it began in 1994. She is a keen advocate of raising money for emerging artists who are struggling financially; the scheme has raised £1m so far. The anonymous postcard sale is a format that has gained popularity, particularly among charities, but that doesn’t diminish their power, the artist says. “The more attention that is drawn to the victims of abuse the better, and I hope people will spend lots of money on these [Deutsche Bank] postcards. There will be something for everyone; all artists are different.”

Elizabeth Magill

The Irish painter Elizabeth Magill, who has a conference room named after her at the Deutsche Bank headquarters in London, is no stranger to philanthropy. This year she has produced work for no fewer than four charities, including a project with the Imperial Charity marking the National Health Service’s 70th anniversary.

A decade ago, Deutsche Bank acquired a set of 10 lithographs of landscapes by Magill, which have inspired the artist’s postcards. “I wanted to do something that directly relates to that series of prints,” she says. The artist is represented in ‘Another World’ by the painting Bonn 2 (2003), which she describes as “not a landscape as such, but more like a suggested backdrop to how I feel, think and interpret the world”.

‘Bonn 2’ (2003) by Elizabeth Magill

For Magill, an exhibition of women artists, coupled with the postcard project, could not be more timely. “Because of the #MeToo movement and the highlighting of the gender pay gap, I think we are entering into another world for women. At least I hope we are entering another world, although it remains to be seen; we thought the same in the 1960s,” she ponders. Despite the hurdles, Magill says she has never been preoccupied with her position as a woman. “I have always been concerned first and foremost with my work. My advice to a young woman today would be: just focus on your work, don’t be dissuaded.”

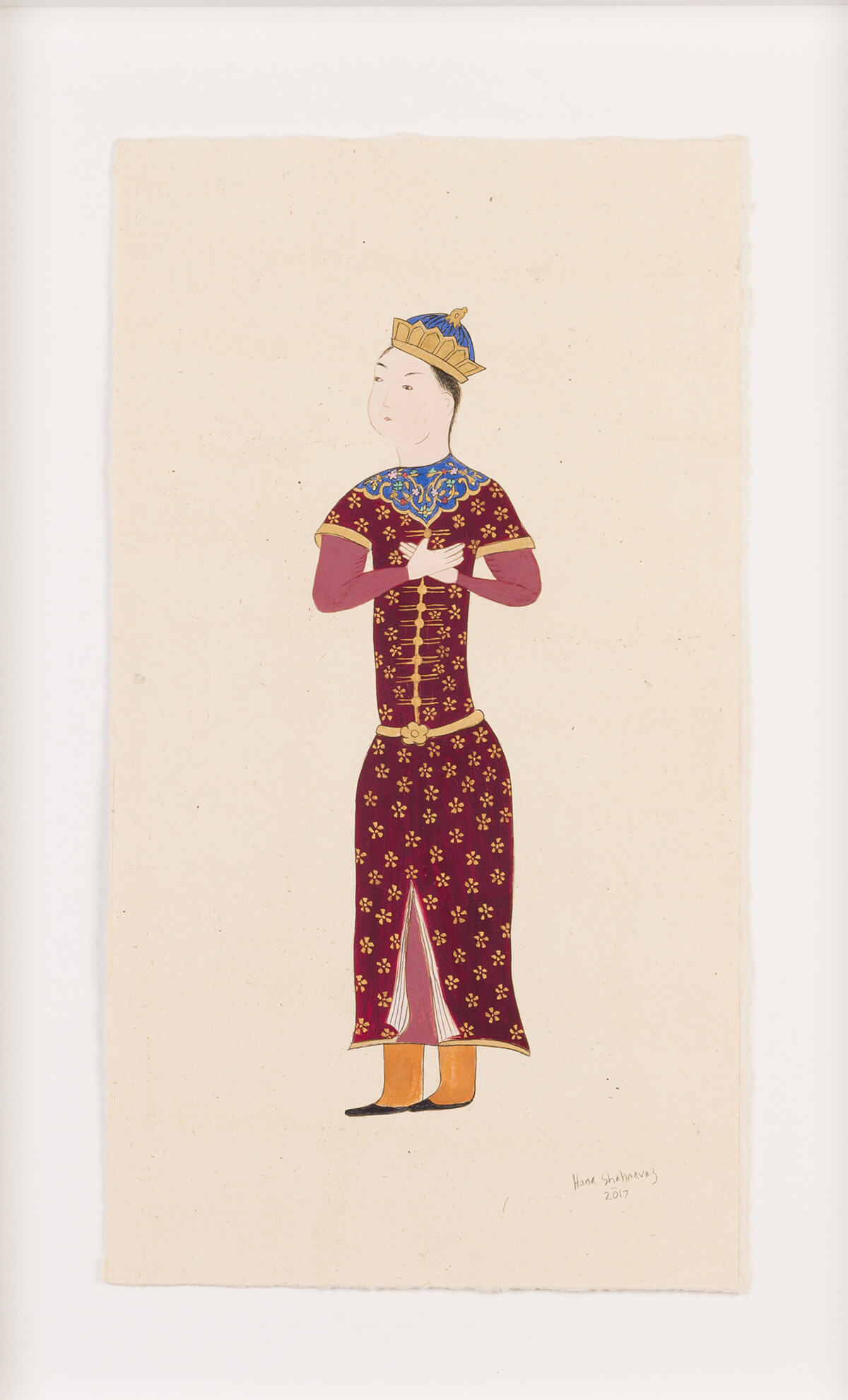

Emel Geris

“To begin with, I did not realize that the postcards would be shown – and sold – anonymously. I saw them as a natural progression of my paintings and just started working,” says the Berlin-based Turkish artist Emel Geris, before wondering: “I hope they won’t be too easily recognized!”

The only difference between the postcards and Geris’s typical work is the scale. “I adjusted the series I am currently working on to the card format, nothing more,” she says.

Tracey Emin has selected Geris’s painting, Dahinter (behind) (2017) for ‘Another World’. The work is part of a series that “deals with dreams, impermanence, trauma and other similar themes”, Geris says. “I created these pictures spontaneously, one after another, like a diary. I still work with these sorts of themes today, but in a completely different way. To see them after so many years seems like another world.” Geris says the #MeToo debate is part of a long-running narrative that is likely to continue for some time. “As long as this strange world keeps rotating, it will probably always be important,” she says. “We have to keep striving to make things better.”

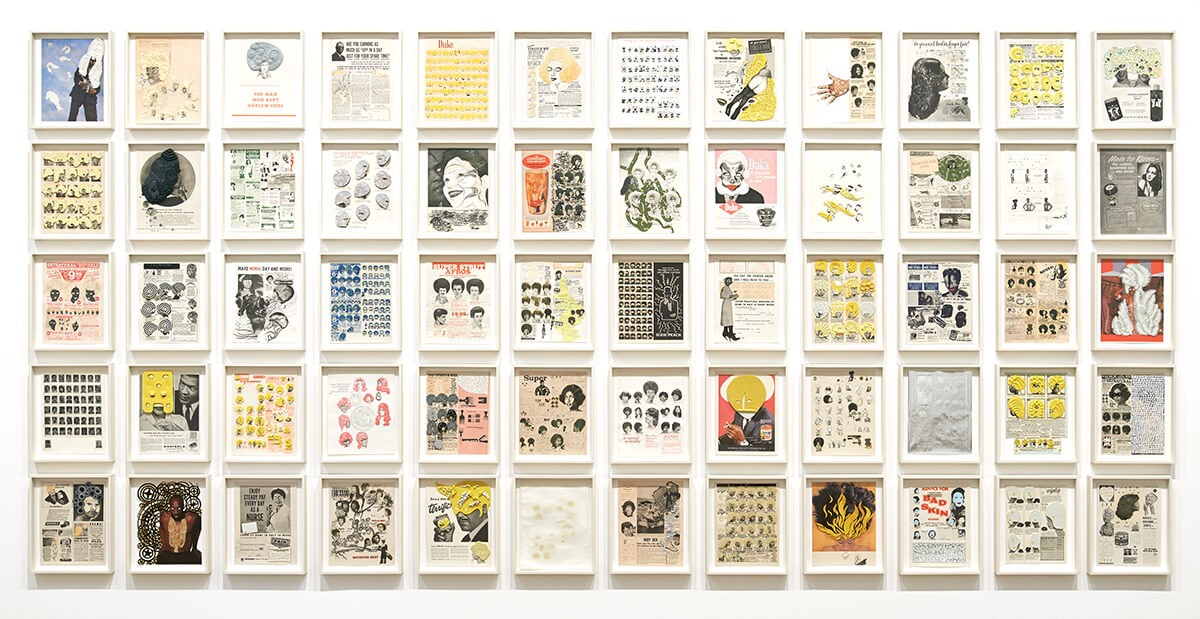

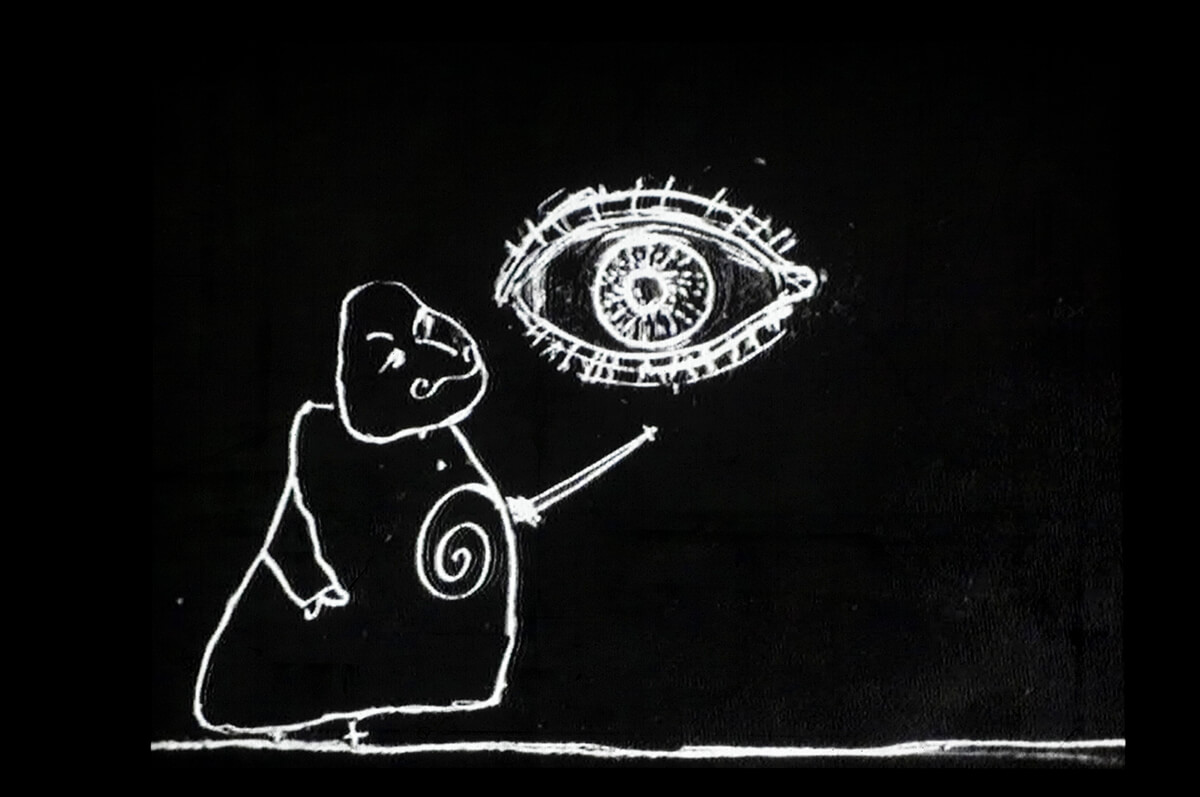

Rosemarie Trockel display

Twenty-one watercolor sketches by the German artist Rosemarie Trockel, many of which depict heads in various guises, have been selected by Tracey Emin to hang in the wide corridor of the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounge that leads to the fair itself.

Most striking among them are a group of drawings that show what appears to be a man’s head, in profile, with a wildly protruding nose, often painted bright red. “Trockel’s ‘Nose’ or ‘Pinocchio’ drawings exist in various versions in both black and white and color, and are mainly from the 1990s,” says Monika Sprüth, the co-founder of the Sprüth Magers gallery, which represents the artist. Trockel has also employed this motif in her sculptures. “They alternate between the figure of Pinocchio, the liar, and a phallic representation,” Sprüth says. “But interestingly the portrait has no clear female or male characteristics. Like many of her works, it deals with gender-specific assignments in a humorous way.”

Rosemarie Trockel, ‘Untitled’ (1994)

Other works on display reflect recurring themes in Trockel’s work, such as portraits of monkeys, people sleeping and domestic objects such as vases and pots. Trockel rose to fame by shifting the way traditionally feminine materials were used – and perceived – by the male-dominated art world, shunning painting in favor of drawing and crafts.

“We’re delighted that such outstanding artists are represented in both the exhibition and the sale,” says Nicola West. “The result is an environment that will not only engage our guests but also give them a chance to participate in a memorable event for a very worthy cause.”

About Art, Culture & Sports at Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank has been enabling access to contemporary art worldwide for more than 30 years with its substantial collection, in exhibitions and through collaborations around the world. Art works: it inspires people to engage with the present and helps them develop creative ideas for the future. Culture transcends borders. It is always an encounter and an exchange. Sports connect people and motivate them to perform and show fairness.

Find out more at db.com/art-culture-sports

Exhibition of Historical Suffragette Postcards

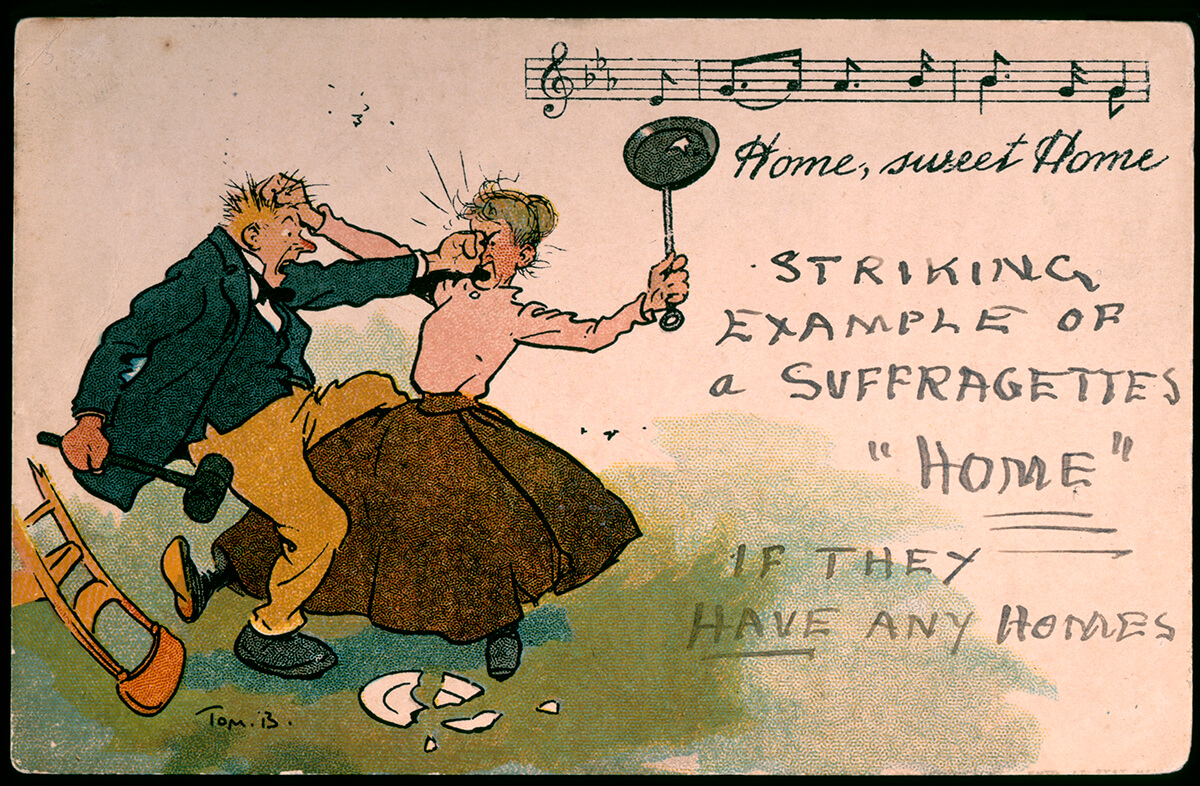

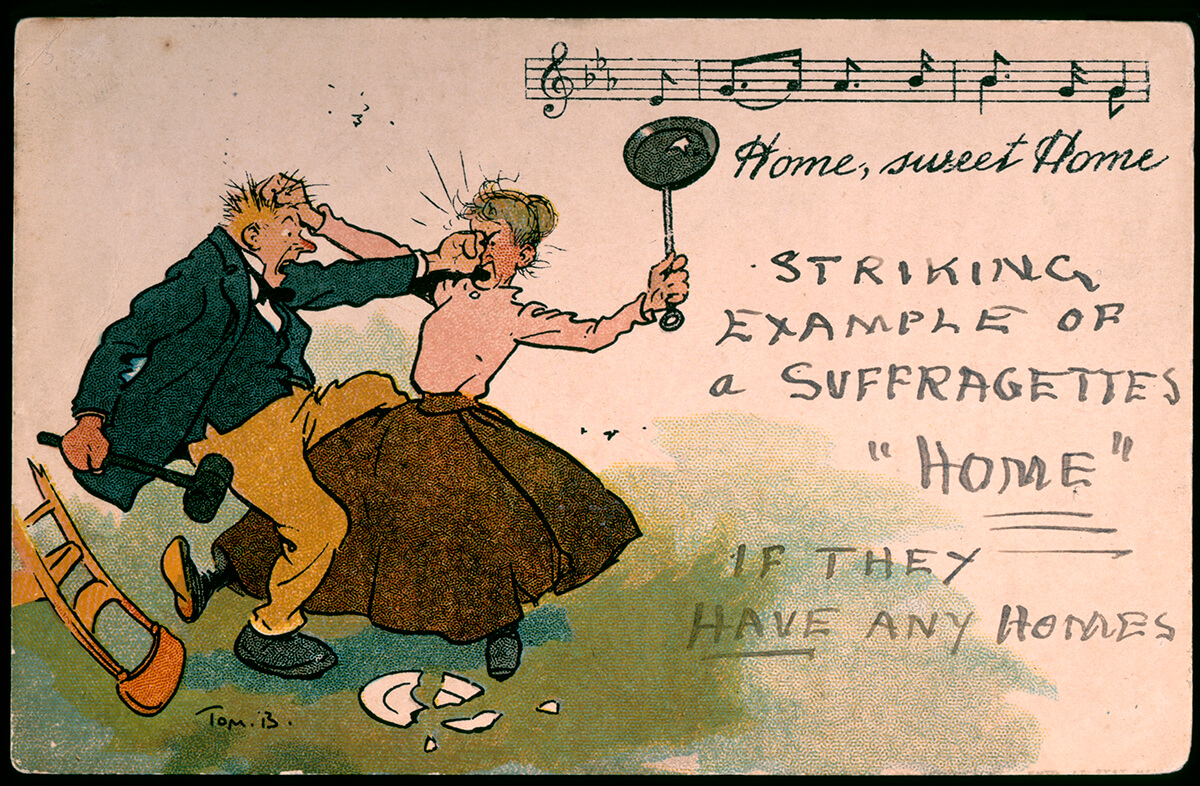

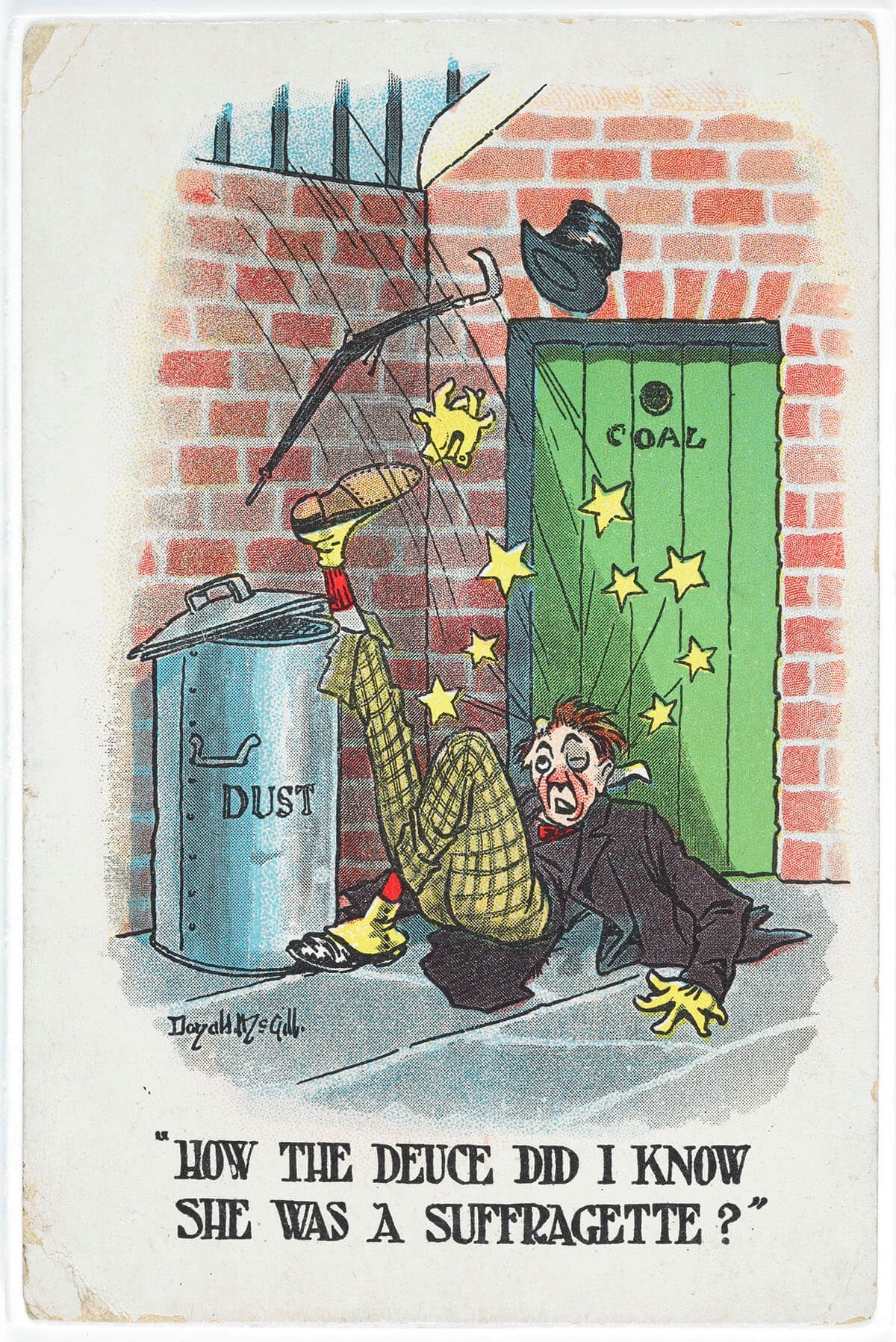

This comic postcard has been annotated with an anti-suffrage message, an example of anti-suffragette ‘hate mail’

A 1907 photograph of “a Lancashire lass in clogs & shawl” being escorted by police from a demonstration outside the House of Commons in Westminster and a cartoon of a stern-looking woman in a meeting hall full of men being asked if she will “go quietly” or be thrown out “by force” are just two examples of some 60 suffragette postcards that will go on show as part of the project.

Deutsche Bank will reproduce postcards from the Museum of London, which holds the world’s largest collection of material related to the militant wing of the suffragette campaign. In 1926, former members of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) came together as the Suffragette Fellowship “to perpetuate the memory of the pioneers”. In 1950, they offered their collection of memoirs and archives to the then London Museum.

Poster parade organized by the Women’s Freedom League to promote the suffrage message

The Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounges will offer a unique opportunity to view postcards promoting both sides of the struggle. Many of the works for the pro-suffrage campaign were produced by two artist groups, Suffrage Atelier and the Artists’ Suffrage League.

“For the suffrage campaigners, it was all about getting the message into the home,” says Beverley Cook, curator of social and working history at the Museum of London. “They wanted to raise the profile of the campaign and present it not just as something concerning politicians, but integrating the fight into every part of life.”

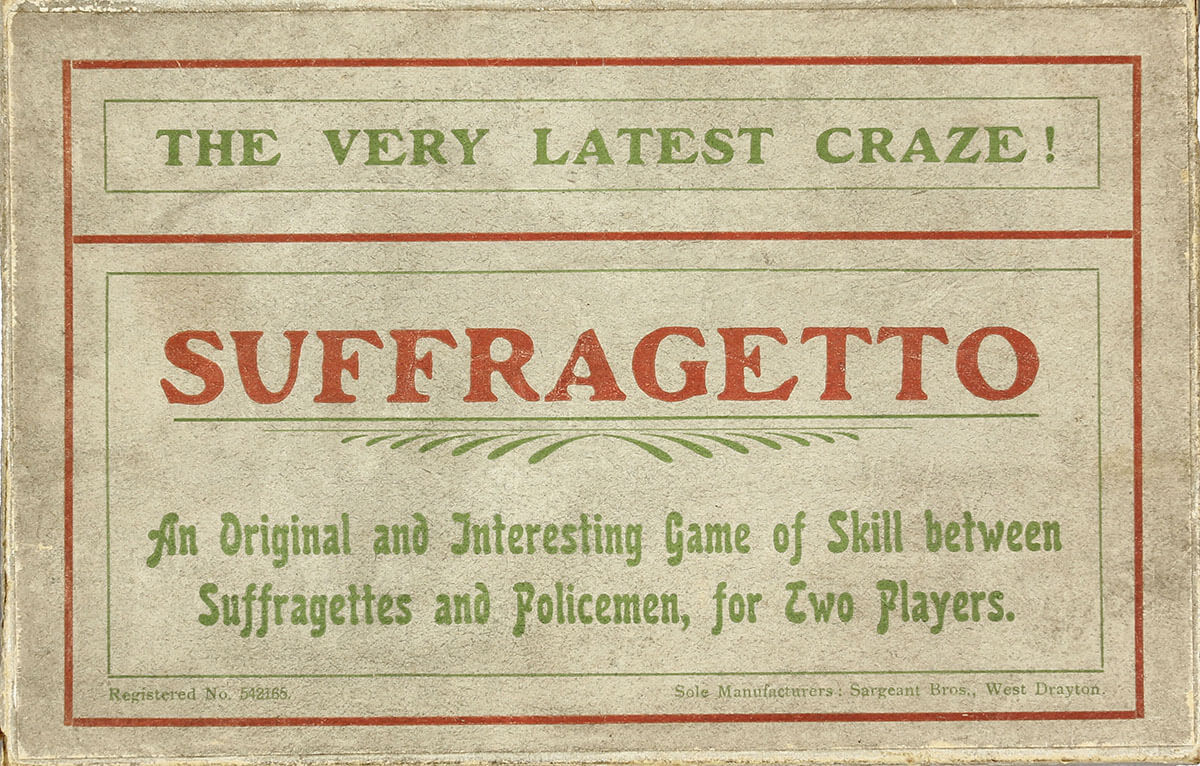

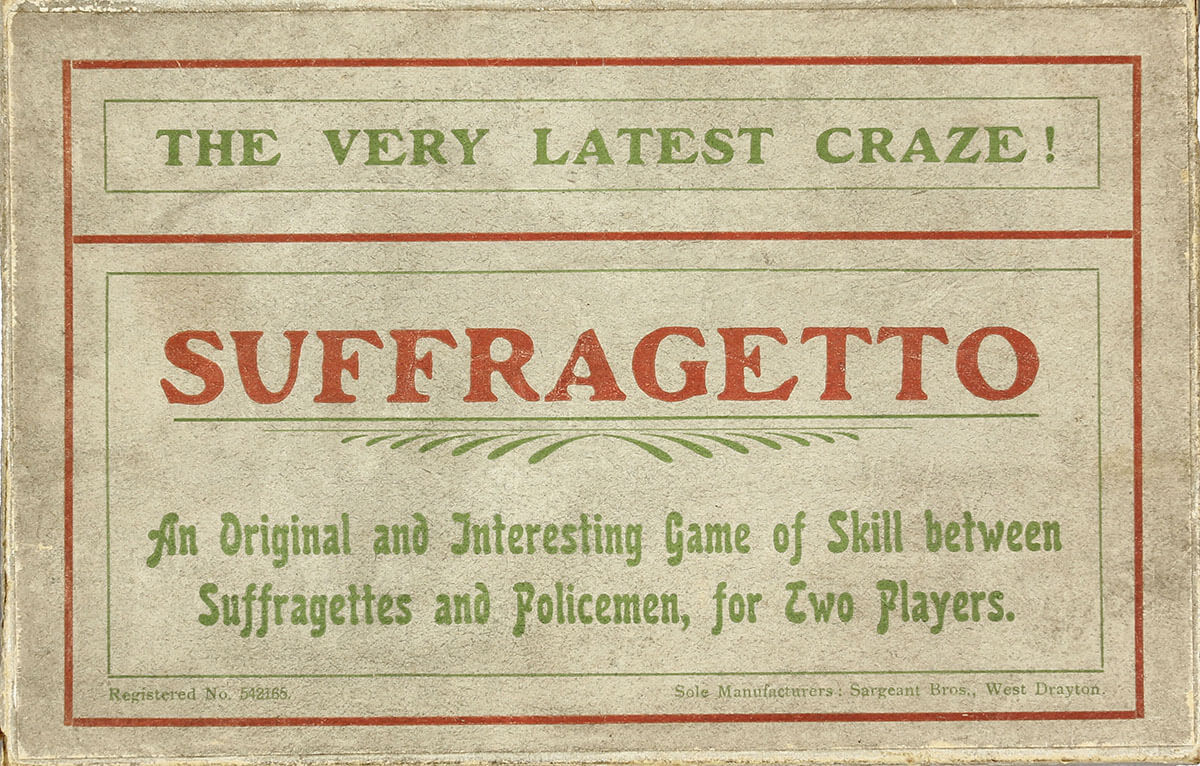

Suffragetto, a board game produced by the Women’s Social and Political Union, from the exhibition ‘Sappho to Suffrage: Women who Dared’, at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, 2018

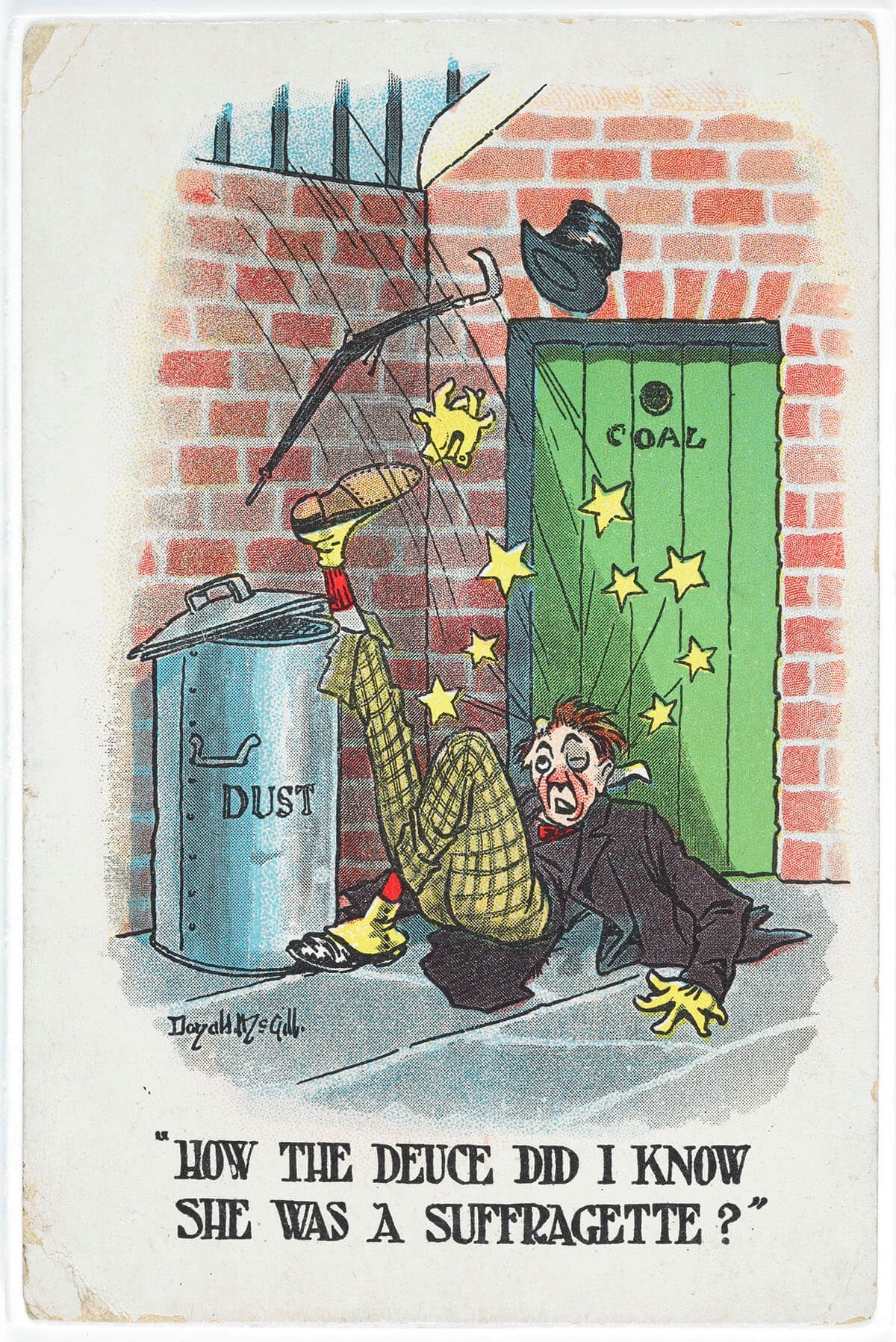

On the other side of the political fence, satirical postcards mocked suffragettes, often depicting them as harridans or as wives and mothers who had abandoned their duties. “They were less formal ‘anti-suffrage’ and more like comic postcards. They were incredibly popular,” Cook says.

With up to seven postal deliveries a day in some parts of Britain, postcards were an effective form of communication. “They were cheap and would often carry very short messages, like ‘See you tomorrow at 2pm’. The telephone was not widely used at the time,” Cook explains. The WSPU and the WFL, which had suffrage shops in nearly every high street, with 19 branches in London alone, were popular outlets.

Commercially produced postcard satirising the suffragette movement

So just how effective were the postcards? Financially, they “added to the suffragettes’ war chest”, Cook says, noting that the sheer number in the museum’s collection (several hundred) indicates their success. “The fact that they have found their way into museum and gallery collections is proof of their currency.” Not only that, but they have also inspired a new generation of contemporary artists to produce postcards. As Cook points out: “The campaign is still as relevant today; it’s just a different battle. In essence, it’s all about women working together to become a force for change.”

Suffragette exhibitions in 2018

Sappho to Suffrage: Women who Dared

(Bodleian Library, Oxford, until February 2019)

Votes for Women

(Museum of London, until 6 January 2019)

Voice & Vote: Women’s Place in Parliament

(Houses of Parliament, until 6 October 2018)

A Woman’s Place

(Abbey House Museum, Leeds, until 31 December 2018)

Ladies of Quality & Distinction

(The Foundling Museum, London, until 20 January 2019)

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

Oxford University is the world’s best, according to august publications like

Oxford University is the world’s best, according to august publications like

1. Philipponnat Cuvée 1522, 2008

1. Philipponnat Cuvée 1522, 2008 3. Philipponnat Clos des Goisses 2009

3. Philipponnat Clos des Goisses 2009 4. Egly Ouriet Les Crayeres, Ambonnay, Grand Cru, Blanc de Noirs, Brut NV

4. Egly Ouriet Les Crayeres, Ambonnay, Grand Cru, Blanc de Noirs, Brut NV

Recent Comments