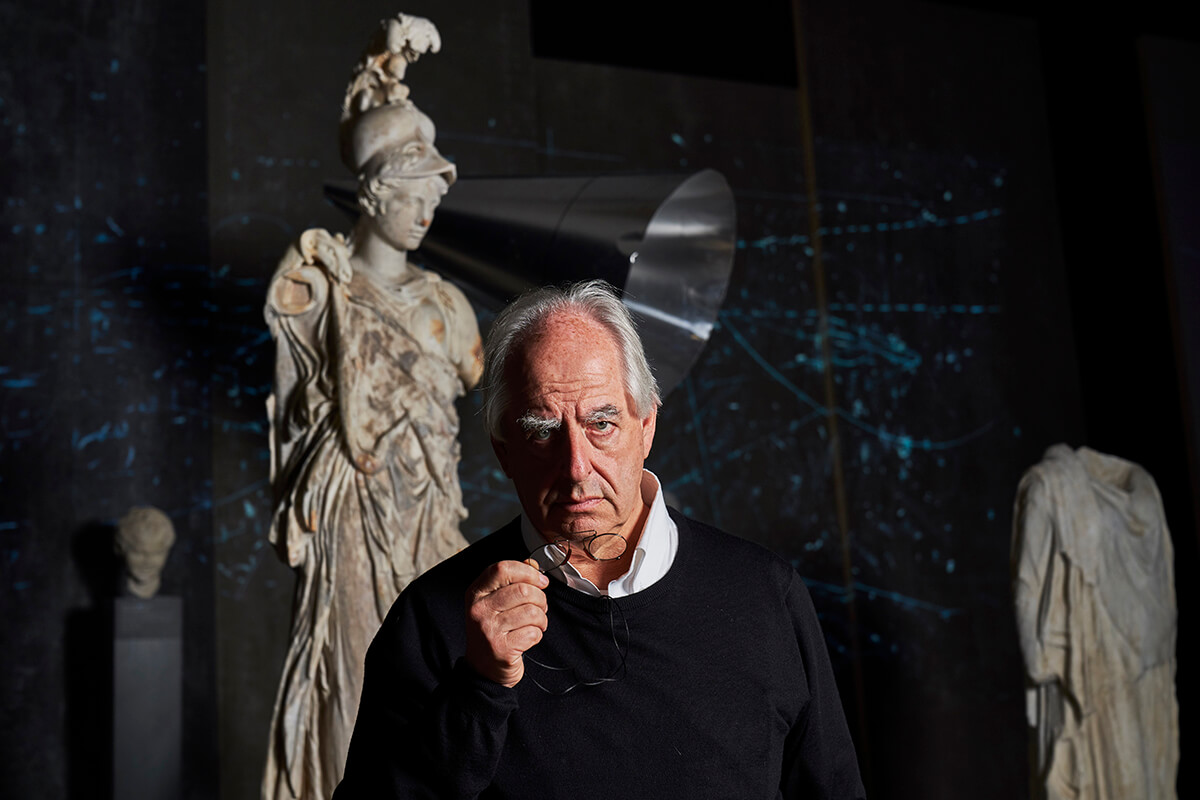

As the globe’s art lovers gather at Frieze London, Anna Wallace-Thompson interviews one of the world’s greatest living artists exclusively for LUX. The expansive career of William Kentridge has seen him design opera sets, stage multidisciplinary performances and create hard-hitting and poignant drawings and animations. His work explores the legacy of apartheid, as well as the human condition, and the ever-repeating cycles of history and memory.

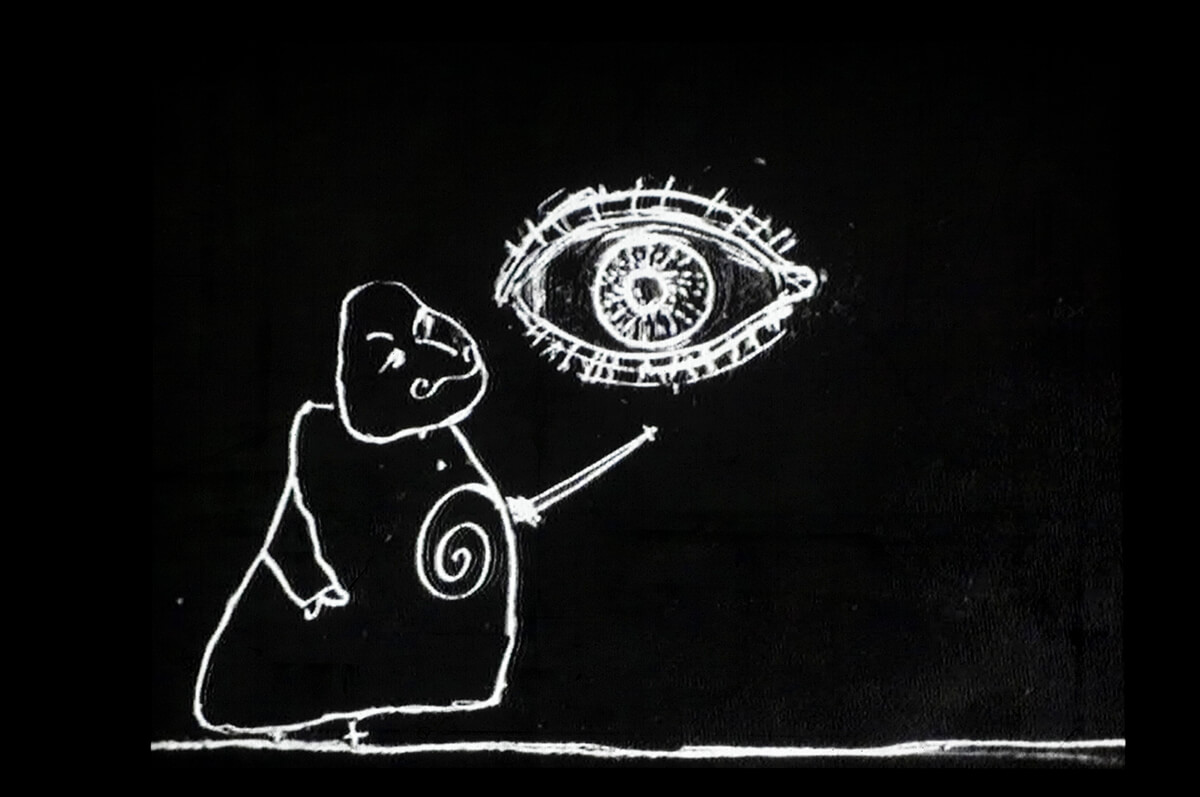

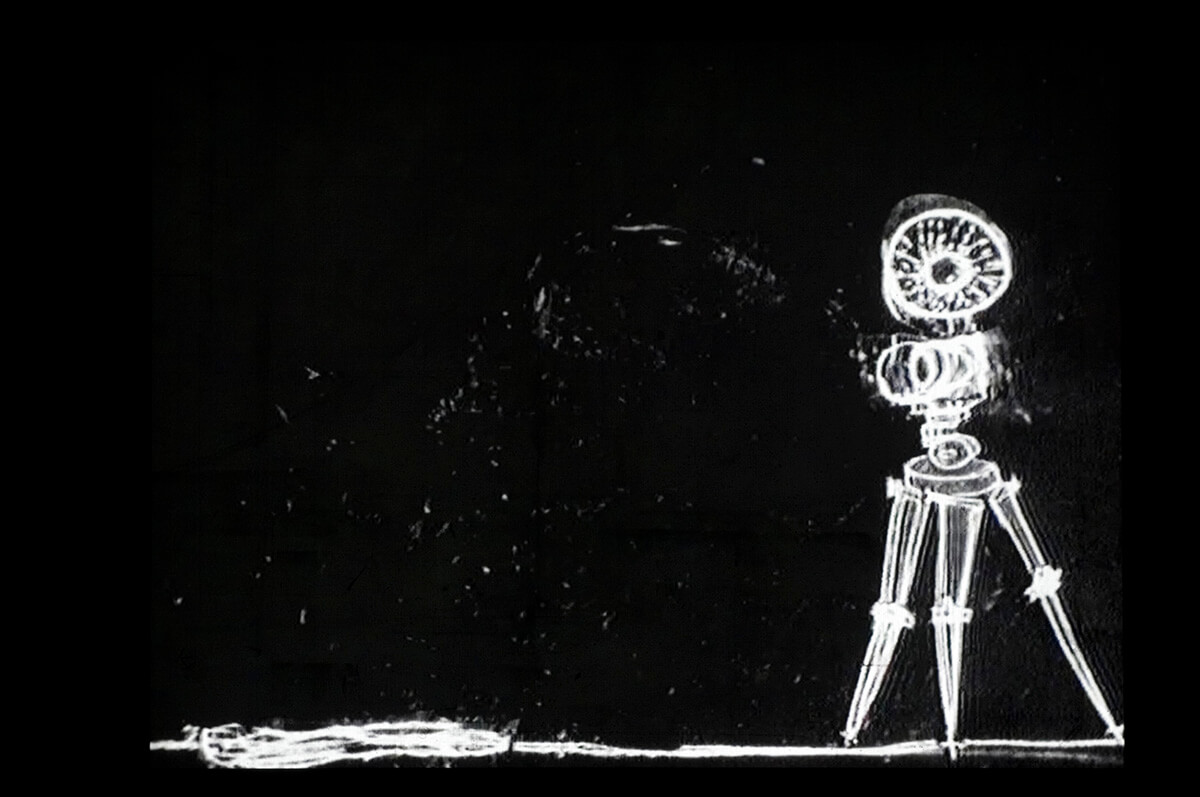

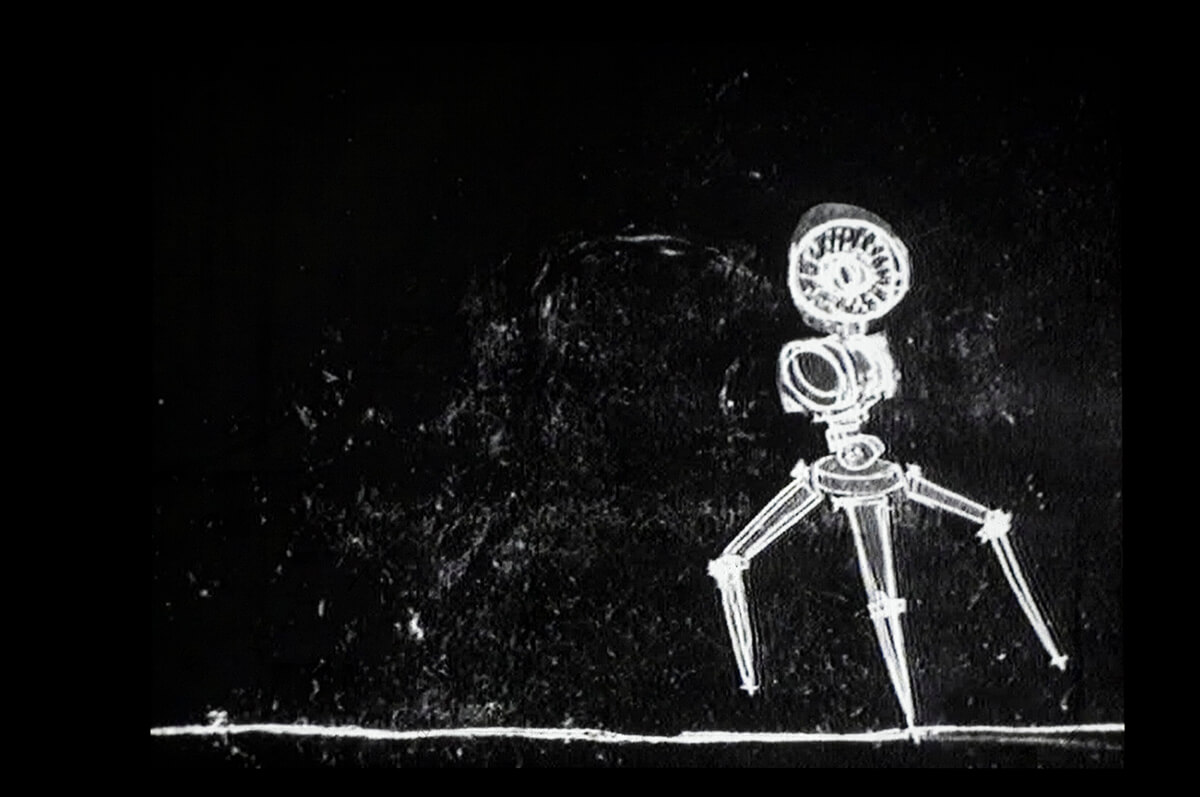

When William Kentridge was three years old, he wanted to be an elephant. At 15, he declared his intention to become a conductor, but was somewhat crestfallen to discover one needed to know how to read music in order to do this. In his twenties, he decided to attend theatre school, and it was there, he says, that he found the confidence to realise he would never become an actor. At 30, a friend broke the news to him: stop calling yourself a technician, or a set designer. You’re an artist! No more talking about ‘falling back’ on a sensible career – time to sink or swim. This should have come as no surprise, for Kentridge had always been drawing and creating – “to make sense of the world”. At 34, he had a breakthrough. His 1989 animated film Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris introduced an intrigued audience to the first of what would become nine films chronicling the rise and fall of the characters Soho Eckstein, his wife, and her lover Felix Teitelbaum – all brought to life, in charcoal, through a unique draw-and-erase stop-motion animation technique.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

Carnets d’Égypte (2010), a multimedia ‘excavation’ of ancient Egypt

In fact, the world of William Kentridge is defined by those dark, deft lines of charcoal, which, as he explains to me, “make us aware of the work we do in recognising what we are looking at”. They capture, in a few strokes, the nuances of bodies and personalities, joy and heartache. When animated, they appear and disappear over and over to create living, breathing figures; the erased traces of lines remaining in the background, marking the passing of time and the endurance of memory. Now, at 63, Kentridge is often referred to as South Africa’s Picasso, and his fiercely intelligent oeuvre encompasses those signature charcoal drawings and animations as well as sculpture and theatre. He also creates vast, multidisciplinary performances using shadow puppetry, music, dance and sculpture – so that theatre school wasn’t wasted after all. His work has appeared in museum shows around the world, most recently Thick Time at London’s Whitechapel Gallery (2016–17), and O Sentimental Machine (2018) at Frankfurt’s Liebieghaus. He also debuted a special performance at London’s Tate Modern in July, titled The Head & the Load. The latter is, he admits, is “filling all my thoughts at the moment. It is the most ambitious work I’ve done… even though it is not necessarily the largest.” For, of course, in addition to theatre, Kentridge also has decades of opera design under his belt – and that means whole choirs on stage.

Read more: Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar’s dialogue across time and space

Kentridge is also a striking man. He is not particularly tall, yet appears tall. His sharp features, marked by dark bushy eyebrows are at once stern yet kind, lending him a sort of old world grace and gravitas (it is telling that Linda Givon, founder of his long-time gallery, Goodman, has referred to him as “a genius and a gentleman”). His parents, Sydney and the late Felicia Kentridge, were anti-apartheid lawyers. During his career, the now 95-year-old Sydney defended Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu as well as the family of activist Steve Biko in the infamous Biko Inquest – investigating the death of the Black Consciousness Movement founder at the hands of police. Kentridge has spoken of the pervasive sense of “indignation and rage at the dinner table” during his childhood, as well as a now-famous story during which the young Kentridge, thinking it was full of sweets, accidentally stumbled upon a box full of police photographs of brutalised bodies being used as evidence. Those images, he recalls, percolated in his subconscious and found their way into his work decades later, and it was only then that he himself recalled the incident, and told his father.

‘O Sentimental Machine’ (2015) at Liebieghaus in Frankfurt

With this backdrop of apartheid, it is natural that there is violence in Kentridge’s art, but there is immense, overpowering beauty too. Much of his work is political – a ruthless yet contemplative exploration of the human condition and the ramifications and consequences of apartheid in South Africa in particular, but also events in general. History, for Kentridge, is a collage – a series of intermingling events each affecting the other, and it is his insight into ‘the other side’, the understanding that “everyone’s triumph is someone else’s lament” that gives it such an edge. “I imagine working with Kentridge is what it must have been like working with Charles Dickens or Shakespeare,” the Whitechapel’s Iwona Blazwick tells me. “He is a phenomenon. Of all the artists we’ve worked with, he’s the greatest polymath, and so open and excited to work with other people.”

Scenes from ‘The Head & the Load’ (2018) performance at London’s Tate Modern

This is the reason why, to define Kentridge’s work as exclusively South African would be misleading in many ways. Its impact and appeal lies in its ability to transcend cultural boundaries. Speaking in the documentary, Certain Doubts of William Kentridge, he has explained, “The work is political in that it takes the political part of the world as one of its subject matters, in the same way one could look at love or deception or the structure of personalities, as a subject to endlessly investigate and play with.” For him, it is the ambiguity of any ‘message’ in his work that allows him such freedom – and part of why he loves, and often uses, Dadaist elements, as reflective of a process of not making sense in order to make sense. In many ways, this is the essence of Kentridge, as is his interest in what he has dubbed ‘the less good idea’. He often quotes the adage “if the good doctor can’t cure you, find a less good doctor” – if one idea isn’t working, find the less good one, for that is where the interesting stuff truly happens.

When I meet him, he is in London to unveil a slightly different artistic project, namely, this year’s Vendemmia d’Artista, an annual artist commission by Italian super-winery Ornellaia. The collaboration feels natural, for Kentridge has something of a special relationship with Italy – evidenced most recently by the vast, 550-metre-long processional fresco, Triumphs and Laments, ‘reverse stencilled’ along the walls on the banks of the Tiber (high-pressure water was used to remove layers of dirt from the wall’s surface and create the images).

Kentridge’s Salmanazar creation for Ornellaia’s Vendemmia d’Artista

For Ornellaia’s 2015 Il Carisma, now in its 30th vintage, he has created special wine labels, drawing in charcoal on the pages of old Italian cash books sourced by him from flea markets in Tuscany. On them, he depicts grape pickers and wine secateurs, a shadow procession, as it were, of the people and tools involved in making wine, celebrating “a great harvest of hard labour”. And the secateurs? “I’m interested in things with hinges,” Kentridge explains. “It gives objects an anthropomorphism, and creates things that can walk.” Two of these figures will be realised as three-metre-high, painted steel sculptures and placed in the Ornellaia vineyard itself.

Read more: Entrepreneur John Caudwell on luxury property & philanthropy

The sale of these special bottles by Sotheby’s raised £123,000 for the Victoria & Albert Museum. The star piece, which went under the hammer for £50,000, is a Salmanazar with a mirrored casing. When placed upon a special drawing, it reflects a series of figures, bringing to life Kentridge’s vineyard procession. “The thing about mirror reflections is that you get an image without end,” Kentridge explains. “There is no edge to the form: it has a top and a bottom, but you can keep circling around. In this case it’s a static drawing of wine pickers, growers and makers, and at the Tate it will be humans carrying shadows along a long curve as they circle around a stage.”

Kentridge is referring to his most recent project, an expansive theatrical production marking the centenary of the First World War – and more specifically, the role of the millions of African porters and carriers who served (for the most part unacknowledged and forgotten in the historical record) in that war. The Head & the Load takes its name from a Ghanaian proverb (‘The head and the load are the troubles of the neck’) and draws on Kentridge’s vast experience of operatic production, set design, shadow puppetry, mechanised sculpture, dance and film projection. Debuting over the summer at Tate Modern, it saw Kentridge team up with his longtime composer collaborator Philip Miller as well as choreographer and dancer Gregory Maqoma to create a theatrical, musical procession.

“I am interested in processions for a couple of different reasons,” Kentridge muses. “One is that they have to do with human foot power – people moving themselves along. Obviously, this has echoes of migration, of refugees walking and the idea of human power moving from one part of the world to another.” The other aspect, he explains, is to do with lateral movement, referencing the analogy of Plato’s cave, in a processional work the figures move sideways to the viewer, rather than backwards and forwards (towards and away from). When they pass by us,we become passive, witnesses to the passage of time. “The world is filled with people, with loads on their backs and their heads, walking across the world,” he explains. “What is our relationship to that passage of passing?”

Stills from ‘Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris’

Plato is also key, as shadows have become one of Kentridge’s signature motifs, the use of monochrome (greatly influenced by what he sees as a rather bleak landscape around Johannesburg) evident in his animation works as well as in the use of large-scale shadow puppets and mechanical sculptures. “Colour had so many problems for me, associated with how one used it, that it stopped the question of what one was using it for,” Kentridge has said. “Charcoal, black and white, it’s much closer to writing… instead of writing with a pen, one’s writing in a shorthand with images and the images can always be at the service of something other than themselves – an idea, a theme, a question that’s being asked.”

Read more: Caroline Scheufele on Chopard’s gold standard

The use of shadow processions in his theatrical work, then, is an evolution of his schematic moving figures, as seen in films such as Ubu Tells the Truth, in which he combines moving puppets with charcoal animation. “There is something very simple about shadows, in that you take a basic shape, and when it’s cast as a shadow, one still recognises it,” says Kentridge.

“For example, without having to make a real model of a boat, you can cut out the silhouette of one, and everybody will recognise your boat – even though it’s just a few sticks and some cardboard. So in that sense, it is a sort of poor art form, yet it has a real richness of both allusion and illusion when you watch it.” There is a lot to be said for the democratising abilities of the ‘poor art form’ of silhouettes and puppets – indeed, in the 18th and 19th centuries, cut-paper silhouette portraits became a cheap and affordable alternative to photography or painting. “I hadn’t thought of them in that form specifically, but there is something very simple about them,” Kentridge responds. “A silhouette has a kind of life and a presence. We’re so good at recognising and putting meaning to a shape, so even if we don’t know how to draw something, we can recognise it as it appears in front of us. A lot of the pieces I create, when I look at them on the ground, I can’t quite tell what the image in front of me is, but as soon as it’s held up, and its shadow is cast, it reveals itself completely. I’ll be surprised, even though I made it – you can’t always predict what the shadow will be.”

When it comes to the theme of The Head & the Load, as with much of Kentridge’s work, it deals with historical events, human flow and facts that might otherwise slip through the fingers of history. During the First World War, there were over a million African casualties – of these about 30,000 were soldiers, but a staggering 300,000 were carriers, another 700,000 civilians. “I was astonished at my own ignorance at the start of the project, and the way in which these fatalities devastated different sections of Africa,” he says. “I also had no idea of the 300,000 Chinese in the Western Front, or the hundreds of thousands of Indian sepoys that were in Africa and in France.”

Kentridge’s fresco ‘Triumphs and Laments’ (2016) along the walls of the Tiber in Rome

It seems unfathomable that something like this could be so unknown. “I think this is because, all the air, as it were, has been taken by [the Eurocentric experience of] All Quiet on the Western Front and Wilfred Owen – that’s what we learned in school,” says Kentridge.

“That’s what one found so moving, and had such a strong connection to.” As a nod to this, The Head & the Load does feature a fragment of Owen’s poetry – translated, in true Kentridge Dadaist fashion, into forgotten French as well as a dog barking (“well, it might have metamorphosed now into a crow rather than a dog,” he twinkles) – Kentridge’s way of saying it’s time to remember other things as well, to be aware of someone else’s lament. The work stands as emblematic of the fraught relationship Africa has had with Europe since colonisation of the continent began, what Kentridge characterises as, “Europe not understanding Africa, not hearing Africa, and Africa having all of these expectations and hopes of Europe.” He pauses and smiles sadly. “As somebody said to me: ‘Not one of our dreams came true. Freedom! Oh, we missed the boat again.’ So yes, it’s incomprehensible.”

View William Kentridge’s portfolio: mariangoodman.com/artists/william-kentridge