Maryam Eisler photographs Thomas Croft in the Skarstedt Gallery space in London

Architect Thomas Croft founded his firm in 1995, and has since designed spaces for fine art institutions, London’s great estates, and beyond. In conversation with LUX Chief Contributing Editor Maryam Eisler, he tells us about building the art world

Maryam Eisler: Tom you are closely linked to the art world, whether its to do with projects related to its patrons, the galleries, or the artists. How did this close association develop?

Thomas Croft: The first artists I ever met were Rose Wylie and her husband Roy Oxlade, who at the time were pretty unknown, and my first ever job was in the 1980s designing their home studio.

Before starting my own office, the architects I worked for often did art projects; after graduating from the RCA my first job was in New York for Richard Meier who had just won the Getty Center in LA. Then back in London I worked for Rick Mather who had just got his first gallery job for Leslie Waddington in Cork Street. After that I worked on the Kerlin Gallery in Dublin for John Pawson, and also with some of John’s great collector clients like Joe and Marie Donnelly. Being able to collaborate with creative patrons who had such high-level architectural objectives was a bit of a revelation for me at the time.

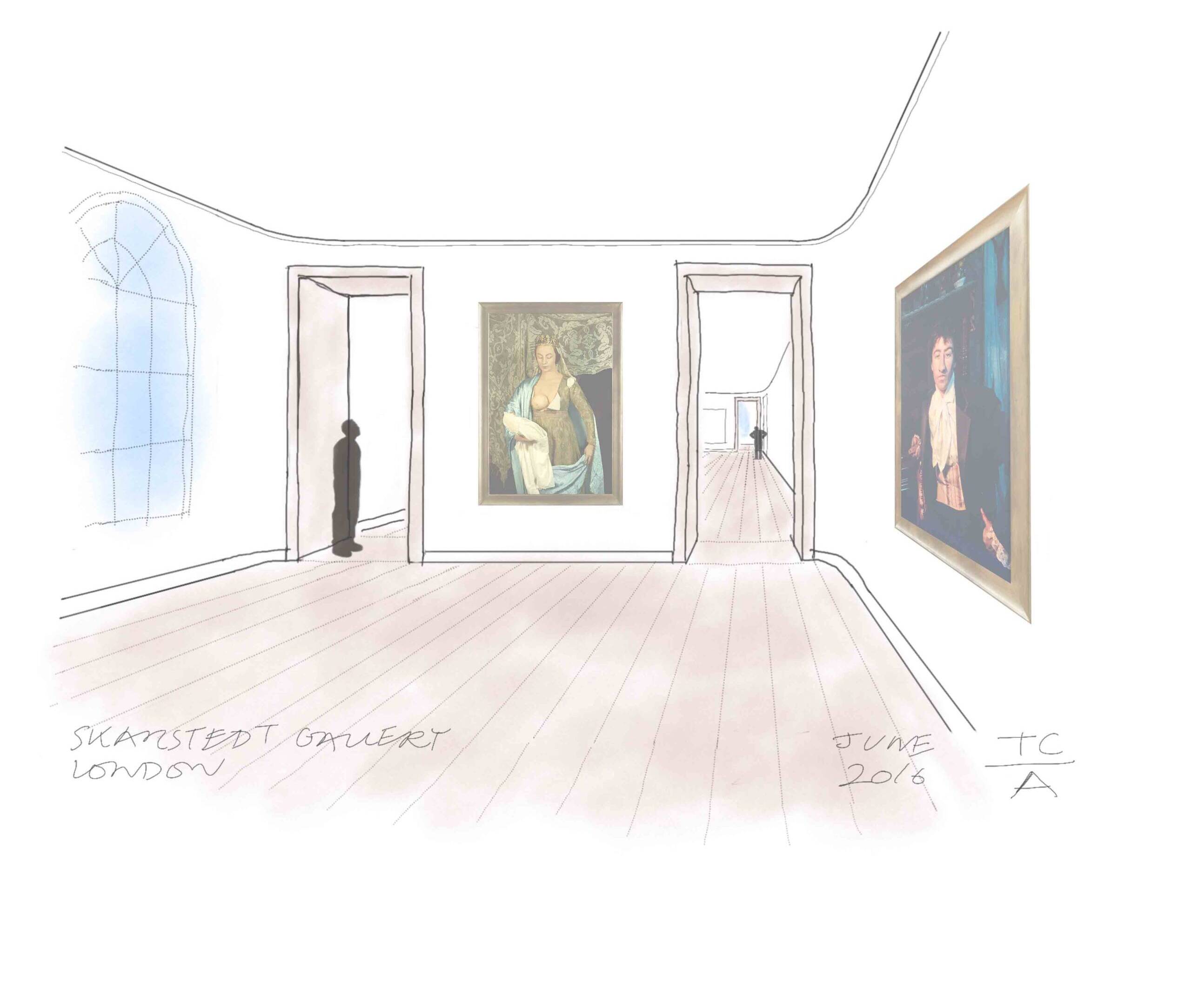

Plans for Skarstedt Gallery London by Thomas Croft Architects

When I started working on my own, quite a few of my jobs were art-related. The first was Timothy Taylor’s original gallery, and then subsequently Ordovas Art on Savile Row, David Gill on Duke Street, and Sotheby’s New Bond Street where we were master-planners for a long time. We’ve done a couple of galleries for Skarstedt, first on Old Bond Street and then on Bennet Street. We also designed Per Skarstedt’s flat in the historic Albany building in Piccadilly, where we’ve worked extensively. And of course there’s often a cross-over between art collector and art world professional projects; Yana Peel’s London family home is a good example.

Read more: Is this the greatest wine collaboration ever?

We’re currently reworking Cromwell Place’s arts hub in South Kensington; it was originally designed by others but constraints beyond their control conspired to make the layout feel very confusing. We’re moving the front door to a completely different street to simplify the user experience and greatly improving the hospitality offering. There’s going to be a big relaunch this Spring and it’s been fun working on a much bigger scale than a normal stand-alone commercial gallery.

Cromwell Place’s Arts Hub in London, redesigned by Thomas Croft Architects

ME: What was the first experience that sparked your interest in architecture?

TC: It was as simple as meeting architects as a child. They seemed like nice people, lived in nice houses, and it seemed like a nice thing to do. But I also remember being fascinated by how the world looked on a macro scale – why did a Swiss house look different from an English one?

ME: Your work has a distinct and recognisable aesthetic to it. Simple, elegant lines with a focus on volumetric spaces that invite light. How flexible are you when it comes to evolving or adapting that style?

TC: We believe in a style for the job; we’re always trying to assess the client and the site in order to evolve what works best, which in dense urban situations often also involves simultaneously bringing the local planners along for the ride.

Thomas Croft photographed by Maryam Eisler, in the realised Skarstedt London space

We work on a lot of historic 18th and 19th century buildings which inevitably requires a certain stylistic adaptability. Our biggest ever project, in terms of cost, has been a recent renovation of a Fitzroy Square house originally designed in 1790 by Robert Adam. By the early 20th century it was the Omega Workshop’s HQ and then later it became an NHS foot hospital in which all the original Adam design had been stripped out. Our job was to create a historically authentic but totally new speculative Adam interior that also worked beautifully as a modern family home.

The exterior of the Royal Yacht Squadron, photographed by Richard Davies

ME: What was the first building that truly captivated you — where you stood, observed, and felt deeply connected to its essence?

Read more: Top chefs on how to be sustainable

TC: At school I did an A-Level thesis on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Houses. I can’t say that Wright has been a big influence subsequently, but of course he was a towering genius & landed like a thunderbolt in the late 19th and early 20th century.

As a young student I remember Foster’s Sainsbury Centre bringing a tear to my eye, I know that sounds slightly corny now but it was just such perfect realisation of a completely modern architectural idea.

Design for Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes by Thomas Croft Architects, photographed by Richard Davies

Since then, buildings don’t often do that, but Toshima Art Museum by Ryue Nishizawa on an island in Japan’s Inland Sea recently did. It’s a domed building, but extremely large. It’s about the size of four tennis courts inside, but quite low, and doesn’t have any windows. It has holes in the roof, so it’s open to the air. Nishizawa worked with the sculptor Rei Naito who created little spurts of water which come up through tiny holes in the floor, and which then trickle around and, because the floor isn’t quite flat, disappear down other holes in a very randomised way like scurrying insects or drops of mercury. A magic confection.

ME: What is the best conversation you’ve had with an architect and who was that architect in question?

The interior of the reimagined 1790’s house by Robert Adam, photographed by Richard Waite

TC: I have had great conversations with John Pawson because he would say things that you didn’t expect, though I have to say it usually involved John talking and everybody else just listening! I remember him once saying: “it’s not about the walls; it’s about the space that the walls enclose.” Having gone through seven years of architecture school that was a new one to me. So often conventional architectural practice is just about form making and imagery.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

ME: I’m a huge admirer of architecture and deeply fascinated by spaces and the emotions they evoke. Beyond the lines, the structure, and the aesthetic — which are, of course, subjective — I’m curious about the emotional attributes of spaces. How much does the emotional impact of a space influence your work?

The reimagined 1790s house as a negotiation between its classic features and modern design, photographed by Richard Waite

TC: Working on homes is always a deeply personal experience for people. The idea of designing something that makes somebody feel at home is quite tricky and it’s often about trying to have a deep and emotional reading of the client. Homes are an expression of how people are, and some people don’t know who they are and so sometimes it’s our job to try to find out.

Alternatively, some people already know exactly who they are; we worked with Sir Paul McCartney on his home in the Sussex countryside and the most fruitful collaborations are often with clients like him who’ve given a lot of thought to the kind of a world they want to live in, but just need assistance in order to help achieve it.

Plans for a reimagined 1790’s house by Robert Adam, London

ME: Talk to me about layering your work with that of an interior designer.

TC: For homes we’re happy leaving the furnishing to a great interior designer or to the clients themselves. Unusually for architects we like the resulting layering and think it’s all part of the project’s story. We’re very Catholic and enjoy working with designers as diverse as Francis Sultana, Philip Hooper at Colefax and Fowler, Suzy Hoodless, Sarah Delaney, Olivia Outred, etc. More minimalist architects, for obvious reasons, need to have total aesthetic control but that’s just not what we do. In any case, when you’re working with an old building, what you’re doing is a simply adding another layer, so you might as well just accept that and make the best of it.

ME: In your own words, how would you describe your particular style and use of texture?

Notting Hill Villa exterior: ‘you can either express the modernism in opposition to the older building or it all becomes modern’ – Thomas Croft (photograph by Richard Davies)

TC: Our starting point is that we’re modern architects. Working in a historic environment, you can either express the modernism in opposition to the older building or it all becomes modern. We can hold both modern and historic ideas at once, and projects are usually the most successful when there’s a tension between them.

Personally, I like living in a modern space. In London we have a 1970’s house that we bought because the planners and locals would be pretty disinterested in what we did to it; it’s great having that freedom in Notting Hill which is otherwise so heavily constrained.

Notting Hill Villa interior: ‘we can hold both modern and historic ideas at once, and projects are usually the most successful when there’s a tension between them’ – Thomas Croft (photograph by Richard Davies)

ME: What is your dream project?

TC: We’re doing a dream project now I guess – it’s a very elaborate modernist folly in a huge landscape garden in Kent that coincidentally used to belong to my great grandparents. It doesn’t really have any brief at all, which is so different from our regular jobs with their very specific and complex programmatic requirements.

Read more: Coralie de Fontenay on women luxury entrepreneurs

ME: We’re sitting in Per’s (Skarstedt) gallery. It’s a beautiful space with really incredible volumes that you’ve managed to create, allowing light to come through in a basement which doesn’t even look like a basement! It’s sublime! I hear it was George Condo who introduced you to Per?

Transparent Tower Folly in Kent, designed by Thomas Croft Architects

TC: It was a sort of triangulated introduction between George (encouraged by our mutual friend Peter Fleissig), the gallerist Simon Lee for whom we’d done work and who represented George in London at the time, and space agent David Rosen of Pilcher London who specialises in finding galleries their London spaces. So, we certainly had a lot of people rooting for us and Per’s been a great client.

ME: One regret in your personal art collection?

TC: I’ve always thought Richard Hamilton is a great artist and when I was working for Tim Taylor he offered me a Five Tyres Remoulded as a barter in lieu of some fees. However, it’s not a very expensive edition so perhaps I should just buy one now and move on…

A portrait of Thomas Croft outside the Skarstedt Gallery London, by Maryam Eisler

ME: Anyone else on your personal art shopping list?

TC: When people ask that I usually say that I’m just trying to buy back pieces that were sold off by my family in previous decades! In our country home in Whitstable we’ve still got a lot of 18th and 19th centuries family pictures but many of the best ones got deaccessioned in the 1900’s sadly. Three family portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds were sold off at that time, however I know the current whereabouts of two of them and I’m in touch with their owners. In principle it would be great to have them all back – though of course the only problem in buying back family portraits is that one can never sell them again because it’s not like regular collecting: instead it’s about getting the family all back together again!

Recent Comments