Alain Servais is an investment banker and collector of art-as-ideas, whose family collection is showcased in The Loft, a repurposed factory in central Brussels. In a conversation moderated by LUX’s Leaders & Philanthropists editor, Samantha Welsh, Servais speaks with South Asian philanthropist and collector, Durjoy Rahman, about supporting artists who give minorities a voice and make people think.

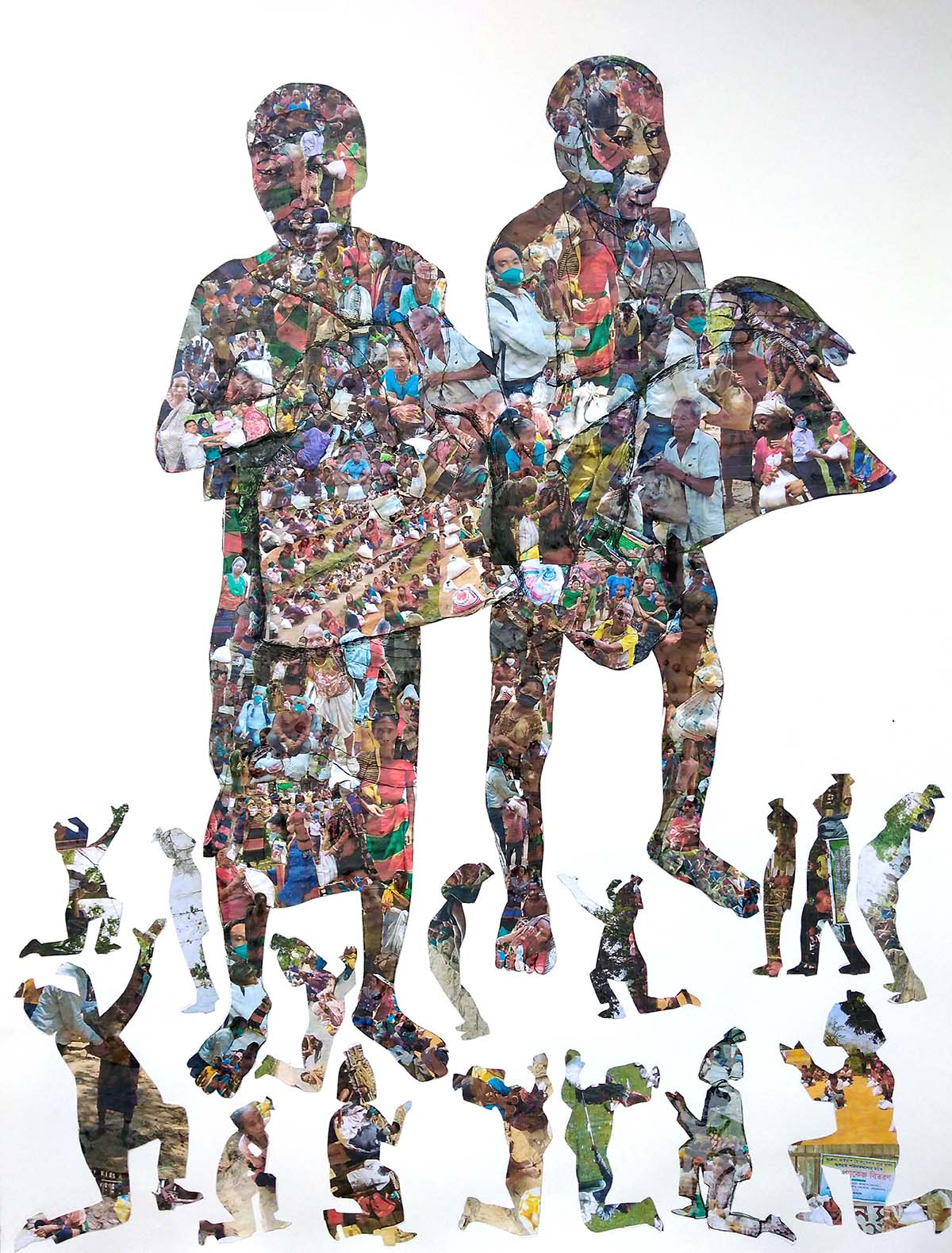

Alain Servais (left) and Durjoy Rahman (right). Photo montage by Isabel Phillips

LUX: How has business shaped your your passion for art?

DURJOY RAHMAN: I started my career at a very young age when I started my business in textiles and garments production. It was when I started exporting that I found that I experienced a negative perception about Bangladesh. I had to engage in a kind of cultural diplomacy when I went to business meetings! I would talk positively about the good things happening in Bangladesh, sharing what was interesting for buyers in course of business development.

ALAIN SERVAIS: For me it was about filling a gap rather than part of my business plan. Investment banking is about trying to understand human nature, anticipating what will happen, asking questions, maybe about the effects of a societal drift to the far right, or changing attitudes to minorities, the potential disruption from new tech and social media, and so on. So understanding herd instinct is very important. In its way it’s pretty sterile as it is all about money. You are missing the voices of so many different people. That is what is interesting in Art.

LUX: How did you become interested in art?

AS: I have no collector-parents, no experience of studying or making art at all, I fell into art by accident. It’s about the convergence of those interesting parts of human nature, professional and private, a kind of curiousness. And that came from working in investment banking, because you are so used to absorbing a massive amount of data and opinion to make decisions.

DR: It was an accident for me too. I was visiting New York and I first saw the silk screens of Marilyn Monroe and Ingrid Bergmann (which in fact I eventually collected). I decided to license and reprint the graphics on a European fashion brand T-shirt, by Replay I remember. It was this fashion x art collaboration which catalysed my art journey.

LUX: So discovery is a big part of your vision?

DR: Yes, I was frequently away on business in Europe and North America, and I would visit the many galleries and museums as I was passing through, always noticing the contrast with South Asia, where we had few institutions despite our long cultural heritage and traditional practices. So that’s why I decided that one day I would do something about it by creating a platform of my own.

AS: I love traveling, discovering other cultures, getting close to parts of the world that people have prejudice and ignorance about. I had the chance to go to Bangladesh and discovered a totally different, very rich culture. The way I process the experience is through bringing back works of art.

LUX: Should collectors open the door to alternative realities?

AS: We should stop making out that collectors are Superman/woman! We are just human beings finding outlets in art, revealing society’s many problems in the process. This is about my own interest in contemporary culture. I have a real problem with nostalgia and the selfishness of it all.

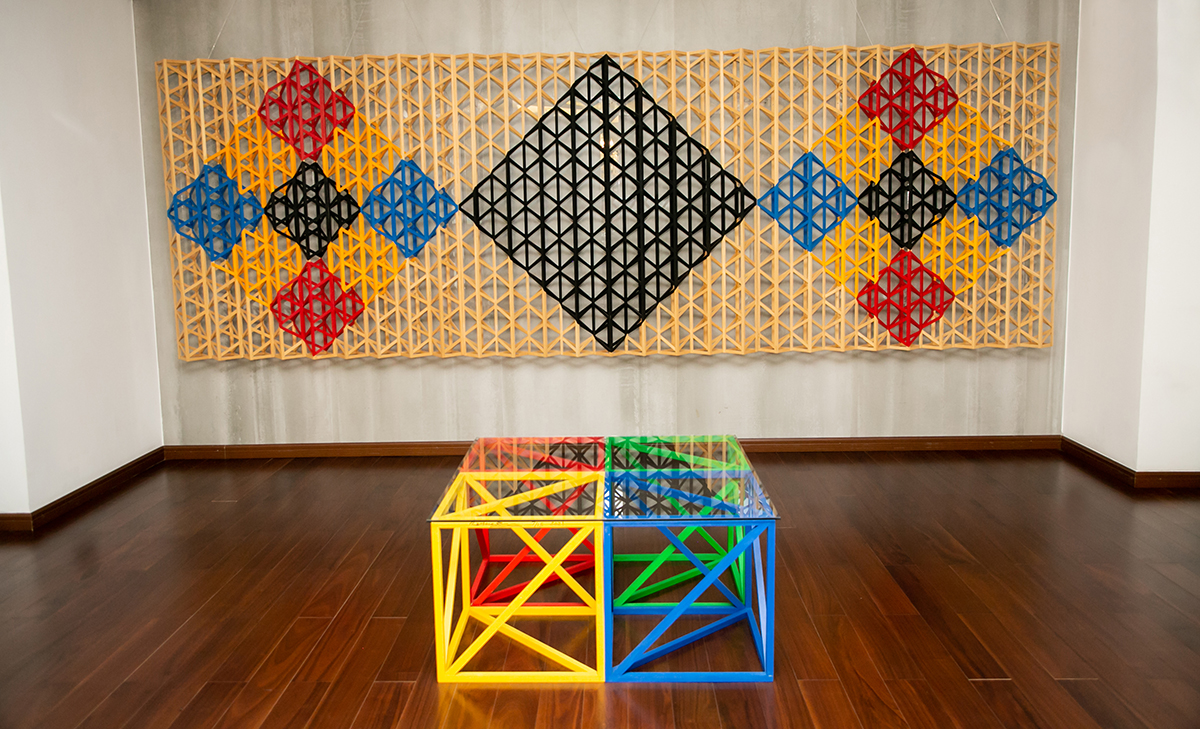

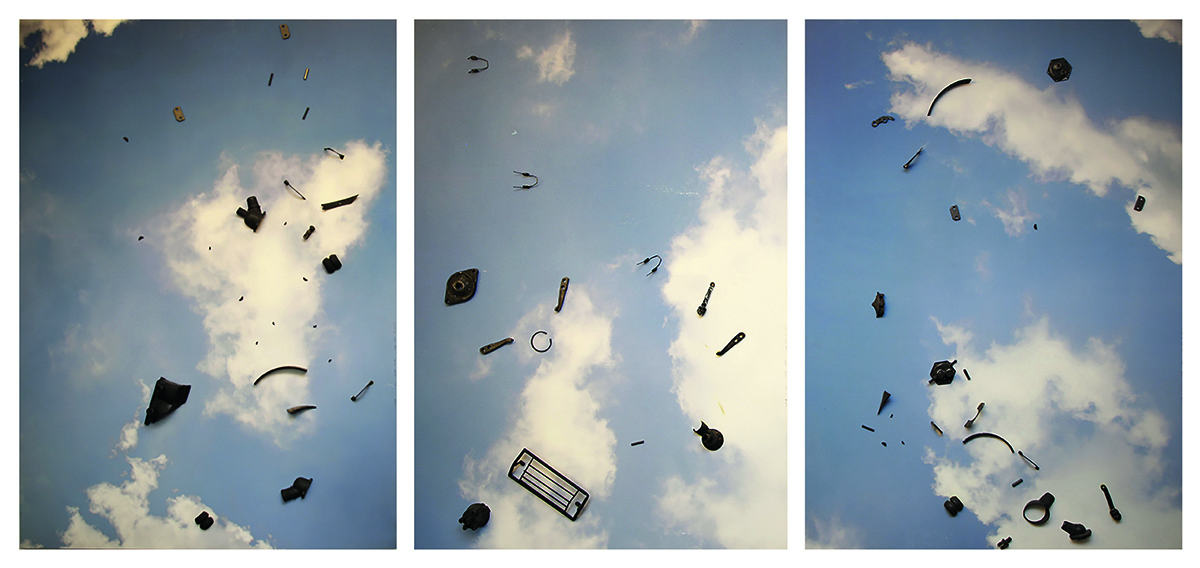

Artworks in a 2019-2020 exhibition at The Loft, the 900 square meter space which has housed the Servais family collection since 2010.

LUX: Is this why you collect ‘emerging’ artists?

AS: Emerging artists for me are the artists who are not selling-out to that nostalgic drive. It’s about the art created today that is worth preserving. Every major museum on the planet is based on the private collections of a few crazy collectors who plugged into whatever was going on in society at that time and collected artists who were expressing that in a particularly advanced way. For instance, forty years ago, Sophie Calle the French installation artist was already anticipating social media and reality shows – people want to watch people. So it’s about collecting and preserving artists’ works really early on, when Society does not yet understand their message.

DR: I agree, I really dislike the term ‘emerging artist’! These are claims not accurate predictions of who will be a great artist. In the art world, there is a structure, a platform, discipline, practice, so we can to an extent deduce who may emerge to be a strong or great artist. As to how successful they will be, that is far harder to judge. If you look at Bangladesh, Bangladesh is only 52 years old, so most artists here have actually been ‘emerging’ since 1971 ie post-Independence. DBF supports artists from this period and empowers them to create innovative bodies of work, influenced by social change. It’s about their context, their transmission of their knowledge and their influences.

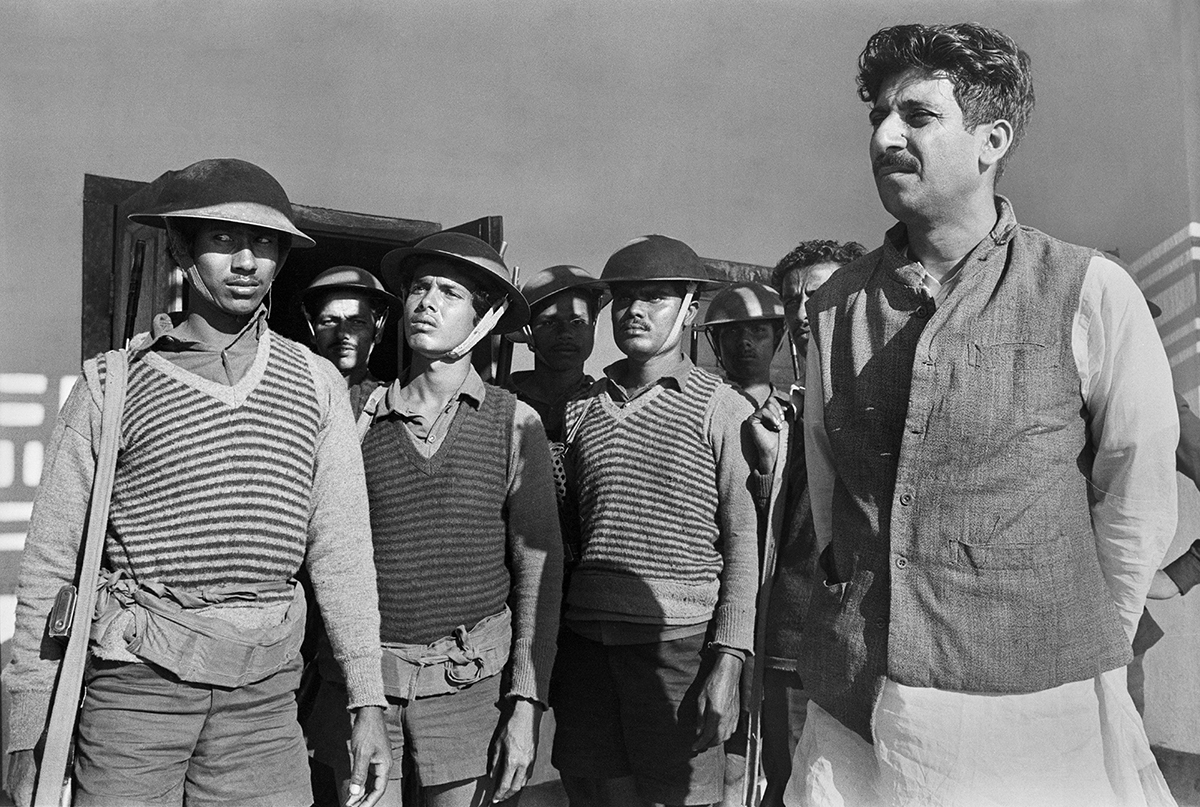

Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation Creative Studio in Dhaka features works from around the Global South including, ‘Orator’ By William Kentridge (right) and ‘Rise of a Nation’ By Raghu Rai (left)

AS: Yes, yesterday I bought an innovative work from an artist from Bali. She had been totally underestimated to the extent she had never, in fact, even been called an ‘emerging artist’. She had, though, created new narratives through traditional Balinese painting and coloration, all pretty outrageous and about sexual liberation, lots of crazy images of penises, vaginas and everything. A good artist is someone that sends a message to the world, and a good collector is the one that understands this message before the masses. They are two sides of the same coin.

LUX: How is art messaging the voices of minority artists?

DR: We should first define what ‘minority’ means. After all, it means different things to different people. Sometimes, I feel like a minority when I enter the room at an event in the global North! It can be discomforting but I get over it with introductions and conversations.

AS: Yes, Durjoy, you’re right, you are a minority when traveling, and I am even an minority in Belgium – because when people visit The Loft they don’t get the art at all and probably think my kids should be taken into care! We are both minorities because we are both free-thinking individuals and non-conformists.

The Great Revel of Hairy Harry Who Who: Orgy in the cellar, 2015, by Athena Papadopoulos, in Dérapages & Post-bruises Imaginaries, the 2018-2019 exhibition at The Loft in Brussels.

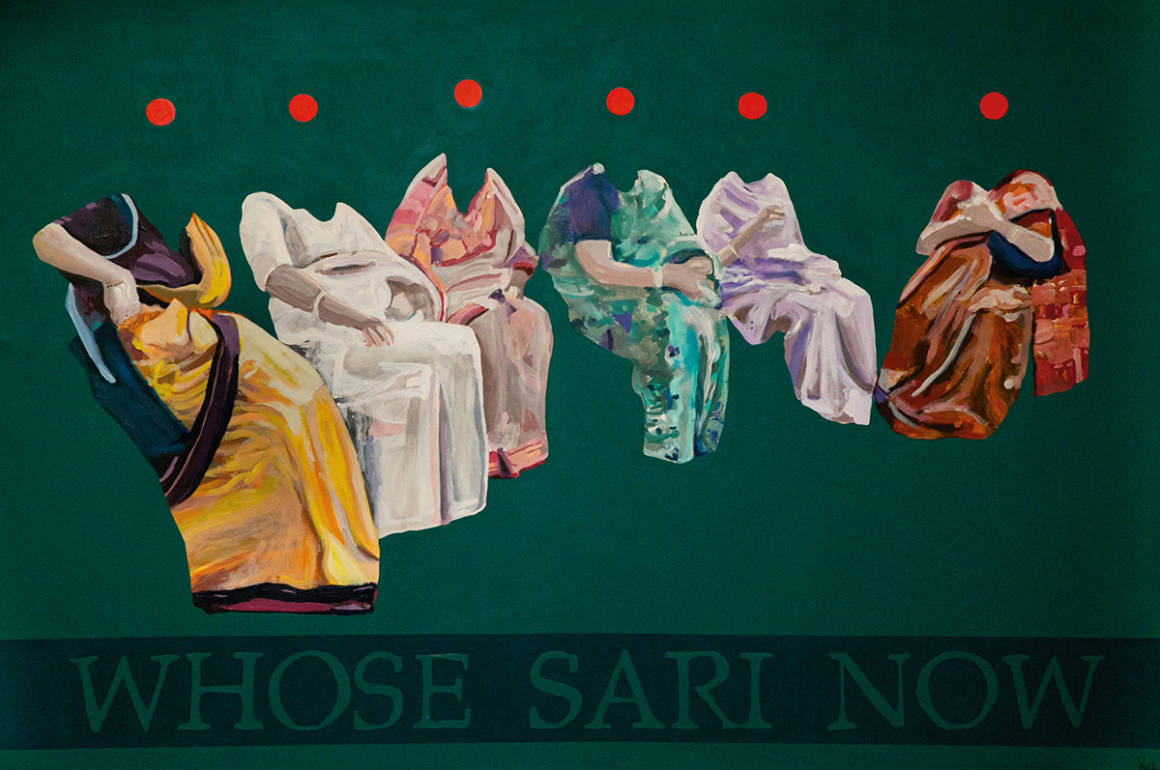

DR: With the minority artists in Bangladesh, it’s not just about their religion or social status but can be about differences in cultural practice. For example, the remote Hill Tracts indigenous communities in Bangladesh are considered to be minorities, so when we talk about the cultural heritage of Bangladesh, DBF showcases their arts and crafts to the global North. By shining a light on their art we are bringing them into the discourse and including them in society. With our Future of Hope program during Covid, we included these indigenous artists from the Hill Tracts and two have become very prominent right now. Similarly, we took our project for Kochi Biennale from the remote northern region of Bangladesh. This was a very significant artwork created by ethnic communities who would never have been exhibited on the world stage.

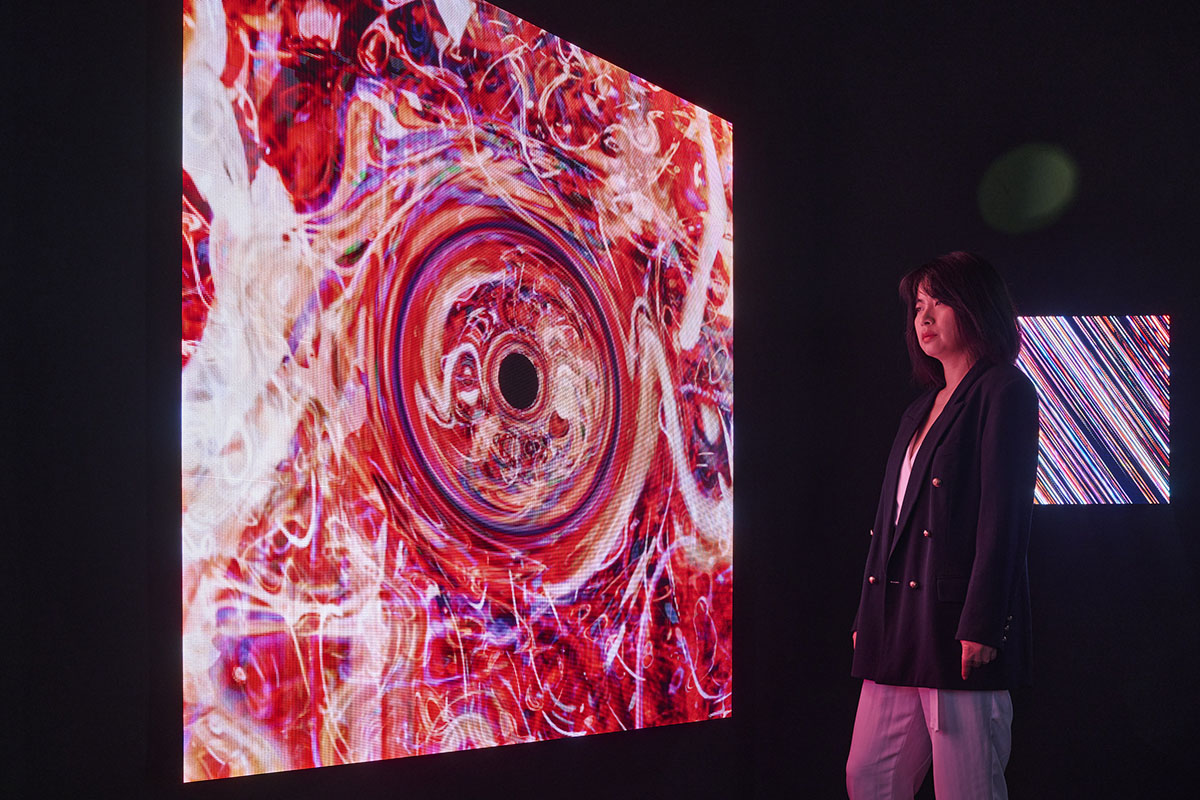

Installation view of Bhumi, with support from The Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India.

AS: I learn a lot from the artists from the global South. Recently, I bought a work by a photographer from Bangladesh. It is an image around infrastructure, bridges, highways and I wanted it not just because I loved the aesthetic but because the message around it was deliberately unfinished. After I’d bought the work, not before, I made sure I sat next to the photographer at the festival dinner and was grateful for the experience of talking with him, on equal terms. It is a two-way business.

LUX: What is the responsibility of the audience toward the artist?

DR: Artists practice as they wish. It’s how the audience accepts their work that is the question. As a collector and as a founder of a foundation, we open up the opportunity for a deeper engagement from the audience with the artist’s social concerns. These activations are beyond direct action and inventions, creating a positive ripple effect. You have to ask yourself, ‘Am I here to change the world or to support a range of alternatives?’ We enable artists to create bodies of work that widen their potential for recognition on the world stage by bringing awareness of their voice and their cause.

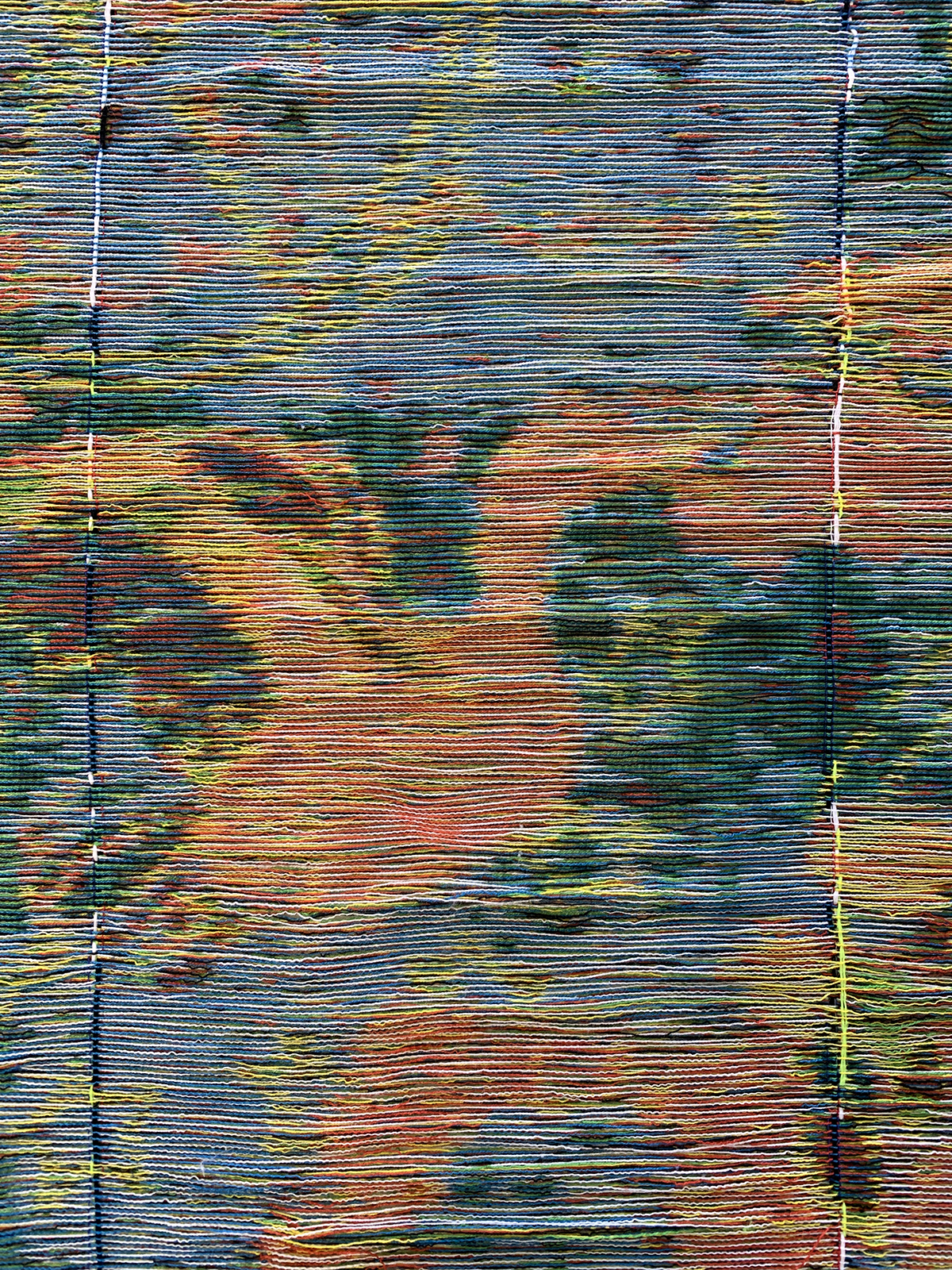

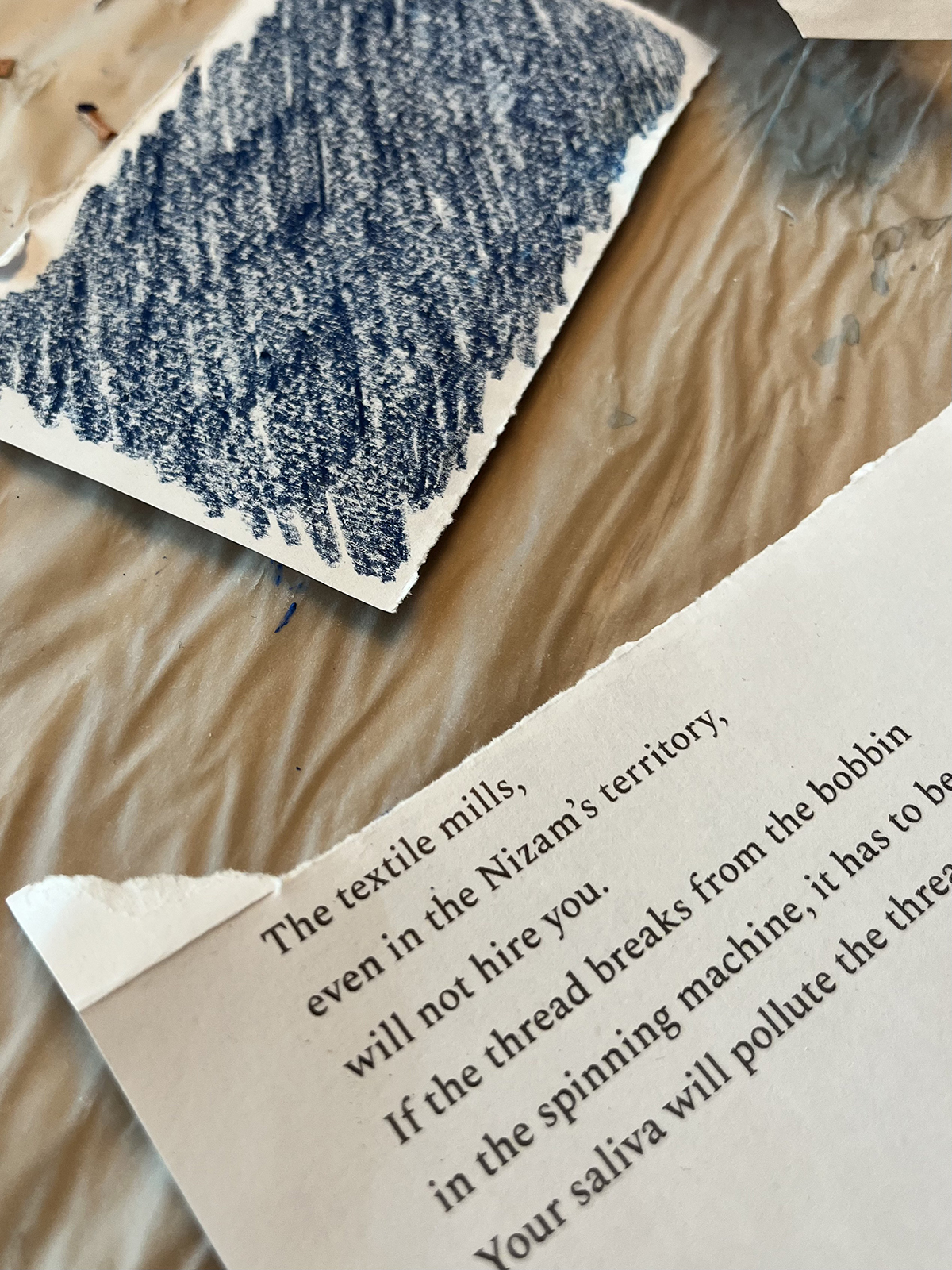

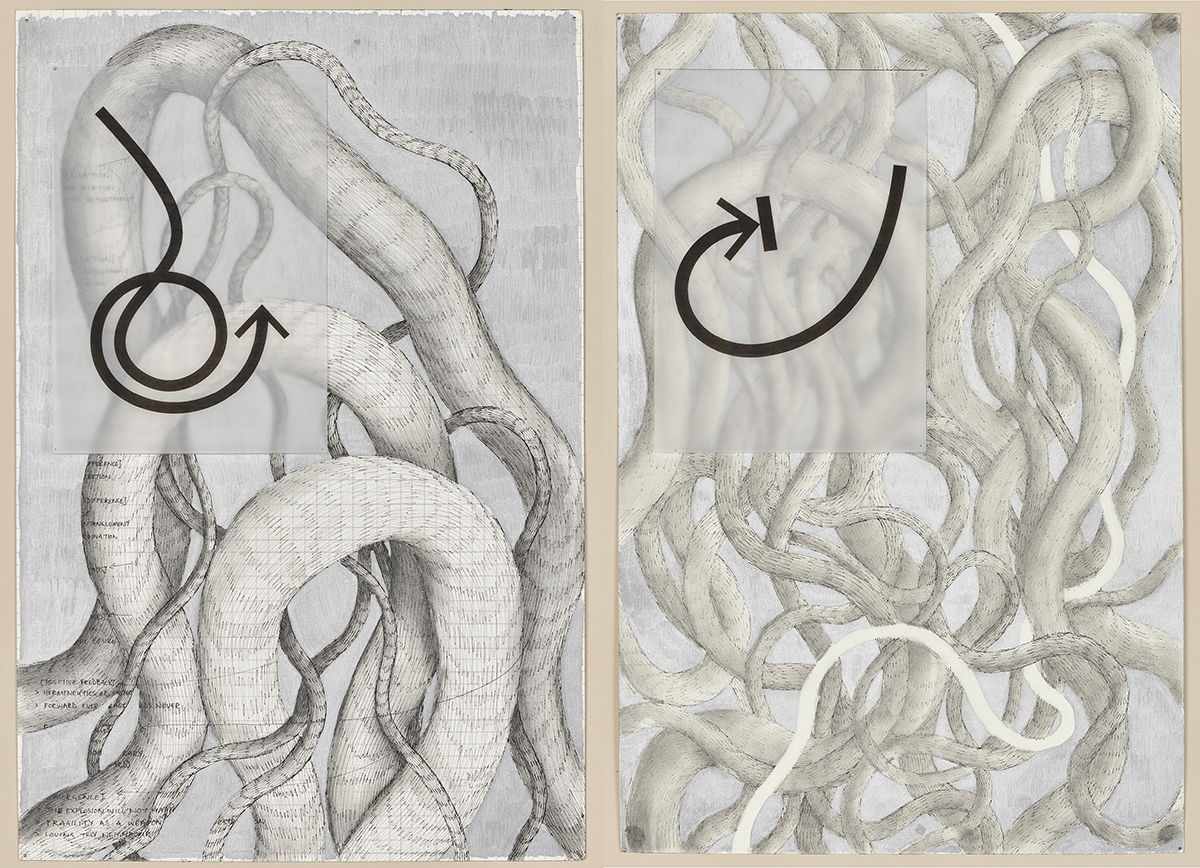

Parables of the Womb by Dilara Begum Jolly at DBF Creative Studio.

AS: As far as the responsibility of the artist is concerned, I don’t like the quasi-deification of the artist. There are so many bad artists around! It is not enough to call yourself an artist to be an artist. I was with a collector in Istanbul last week and he told me he had reserved an exhibition space for a solo exhibition by an emerging artist, emphasising it had to be an artist with no gallery representation. It was to be for six weeks. He actually refused the the first offer, saying “I want to see if artists will fight for it!” For him, the fighting was an important element as so many artists were not thinking about what they are doing and why they were doing it.

LUX: Where do you think your art philanthropy will be, ten years’ from now?

DR: With DBF, we want to be an influential and vital activist who has used the power of art and culture to good effect, to make positive, impactful change in terms of social justice. I agree with Alain, we must question everything and that curiosity must inform our vision for the next decade.

Servais hosts exhibitions from his collection of international contemporary artists at The Loft, where he also hosts artists’ residencies.

AS: Because governments are funding the arts the arts less and less, I spend more and more time documenting the works I’m acquiring! I’m doing this to record for posterity the complexity of the artist’s thinking. I hope institutions give more power to curators to offer opportunities to interesting artists so we have the vital two-way discussions. I think we are going to go through extremely difficult times and I would not like to be this young generation. We need people like Durjoy, we need these discourses, we must give people a voice, and we must make people think!

Find out more: durjoybangladeshfoundation.org

Servais Family Collection on Instagram: @collectionservais

Recent Comments