Tamara de Łempicka, Young Lady with Gloves (1930)

As part on an ongoing monthly column for LUX, artnet’s Vice President Sophie Neuendorf outlines a brief history of women artists, and discusses their recent rise to prominence

Sophie Neuendorf

We define ourselves, as nations and individuals, mainly through our respective cultures. Since the stone age, art has been a signpost for humanity, and a reflection of history and the zeitgeist. Over the past few years, we’ve often been amazed by the discoveries made by archaeologists and what these tell us about generations past and how humanity has evolved since.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Artists were first commissioned to illustrate the word of God for those unable to read and since then, art has evolved to not only depict religious or mythological scenes, but also the joys and perils of everyday life. Especially in Italy, France, and Spain, prominent political, royal, and influential families commissioned artists to portray their lives for posterity.

However, the artists receiving public recognition for their contribution to the documentation of culture, have until, very recently, only been male. But how can an accurate portrayal of humanity take place when women (who make up half of the world’s population) are marginalised or ignored?

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait

Paying a historical debt, the contribution of women to the canon has only been recognised in recent years. The first documented female artists emerged during the Renaissance, during a time when it was either considered not ‘seemly’ and completely forbidden for women to be artists, and several obstacles stood in their way. First and foremost, their training would include the dissection of cadavers and the study of the nude male form, while the system of apprenticeship meant that aspiring artists would have to live with an older artist for several years. This made it nearly impossible for Renaissance women to follow this path, seeing as other “expected duties” took precedent. Florentine artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1653) was one of the few artists able to practice her passion. Trained by her father, she was the first female artist to be admitted to the prestigious Florence Academy of Fine Arts.

Read more: Alia Al-Senussi on art as a catalyst for change

Several years later in France, Neoclassical painter Adelaïde Labille-Guiard (1749 – 1803) became one of the first women artists to be admitted to the distinguished Académie Royale, where she exhibited her works. Soon after, she was appointed Peintre des Mesdames: painter to the King’s aunts. Astonishingly, several male painters were so threatened by Adelaïde, that they spread rumours alleging sexual misconduct in order to discredit her. But she persevered, and became a mentor many other female artists.

One of her contemporaries was the completely self-taught artist Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. Active during some of the most turbulent times in European history, she was admitted into the French Academy as one of only four female members, thanks to the intervention of Marie Antoinette. Forced to flee Paris during the Revolution, Vigée Le Brun traveled throughout Europe, impressively obtaining commissions in Florence, Naples, Vienna, Saint Petersburg, and Berlin before returning to France after the conflict settled.

Joan Mitchell, Untitled (1979)

Only a few years later but on a different continent, American artist Mary Cassatt was born in Philadelphia. Headstrong and independent, she trained as an artist and fled to Europe in order to study Old Master paintings in Spain and France. After befriending Edgar Degas, Cassatt was invited into the Impressionist circle, and by the turn of the century, her reputation was thriving in France. In 1904, she was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. Soon, American artists in Paris sought her blessing and advice, while wealthy Americans sought her discerning eye and connections.

Courtesy of artnet

In the same century, Polish-Russian aristocratic artist Tamara de Lempicka took the French art scene by storm. Forced to flee St Petersburg and the Russian Revolution in 1917, de Lempicka headed for Paris, where she studied painting in the ateliers of Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and quickly found success. By the early 1920s her works were appearing in major Paris exhibitions, such as the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Tuileries. Nicknamed “the baroness with the paintbrush,” she is renowned for her art deco style which oozed cool chic and elegant sensuality.

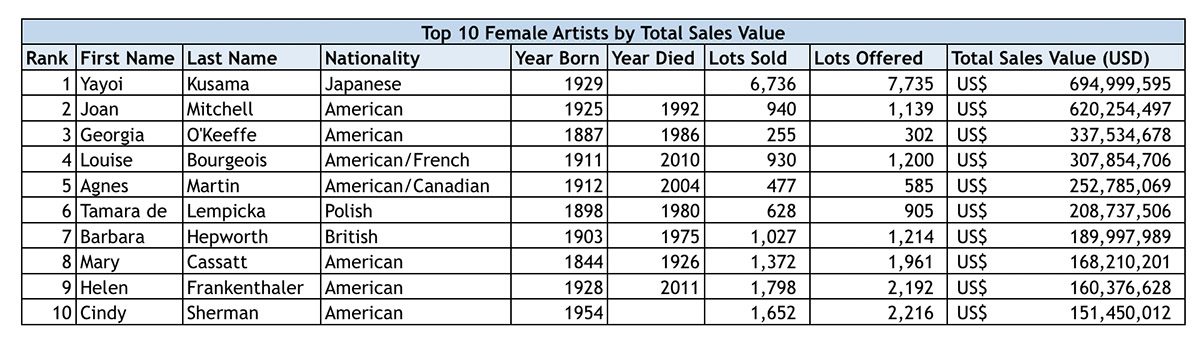

Not long after, but on the other side of the world, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama began painting at an early age. Without any formal training, she emigrated to New York to pursue her passion. Now famed for her psychedelic paintings and sculptures, Kusama remains one of the top 10 highest grossing women artists in the world.

Yayoi Kusama in the studio

That brings us to 2021, the era of ‘me too,’ and a question arises: has the work of women artists been reduced to gender politics and to the circumstances of its production rather than being judged for its quality?

Read more: A prima ballerina dances in the London lockdown moonlight

Even though women artists are finally being recognised and forming a formidable part of the canon, it will take another few years for them to feel completely secure and appreciated in the art world. Ground-breaking artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, or Cindy Sherman have liberated themselves from identity politics and are held in esteem by the quality of their oeuvre.

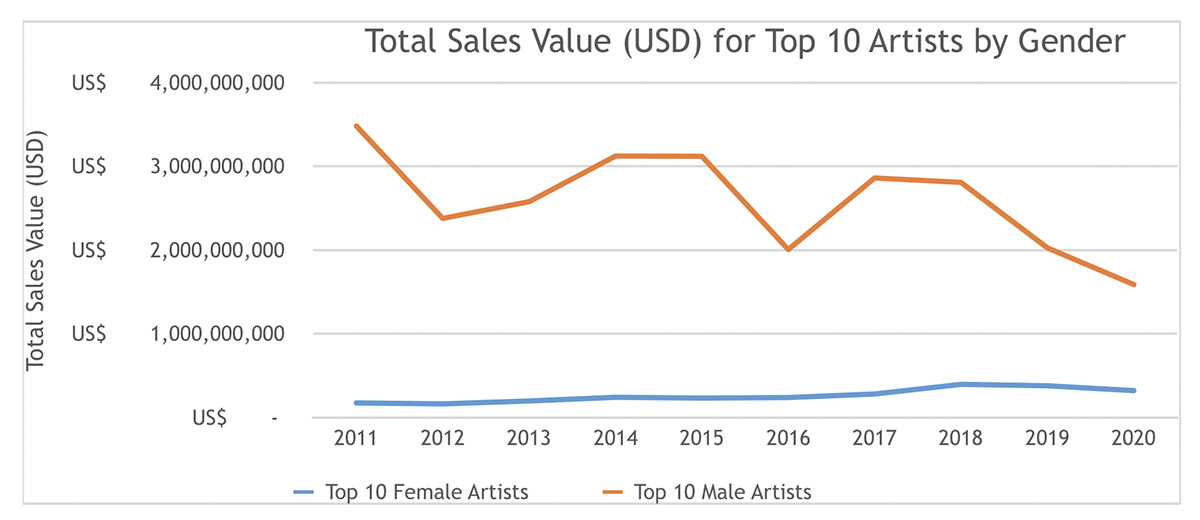

However, regardless of the obvious quality of their work, there is one glaring aspect which hasn’t yet translated: when looking at the monetary value of female artists in comparison to male artists, female artists are still incredibly undervalued. In 2020 alone, the top 10 highest grossing female artists achieved $322,780,748 in comparison to their male counterparts, who achieved $1,590,134,429 (source: artnet Price Database).

Infographic courtesy of artnet

While we can’t undo the past, we can work towards building a richer and more equal picture of art history, ensuring that future generations see us through all facets of humanity. How else, if not through the arts, are we supposed to learn from the past and create a brighter future for humanity?

Follow Sophie Neuendorf on Instagram: @sophieneuendorf