Philip and Charlotte Colbert in their fried-egg suits designed by Philip

In a warehouse in east London, Philip and Charlotte Colbert are creating a world of Pop art and sculpture that is putting them on the global map. Darius Sanai speaks to the dynamic enfants terribles of the London art scene while Maryam Eisler photographs them

At the back of a warehouse in east London, Philip Colbert sticks his head out of a doorway. “Come in,” he says, smiling, while simultaneously holding a conversation with his phone on one ear. “No, it needs to be there tonight. Right,” he says, into the phone. His tone is soft, firm, a gentle Scottish accent is present but inconspicuous, almost shy.

Inside, workers are cutting and daubing in an area full of canvasses and paint, and behind a rail of pop-coloured clothes, four more people are on their phones, sitting at desks. Through a space in the wall is another artist’s studio, this one tidier, less colourful, more precise, hung with sculptures of curved forms and creatures.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

Welcome to the world of Philip and Charlotte (through in the other studio) Colbert, the enfants terribles of the London art scene. Philip has been called all sorts of things, including a worthy successor to Andy Warhol; in his zany coloured suits he is a mainstay of the party (and social media) scene and with his classical education (philosophy, St Andrew’s University) combined with his cheeky-to-outrageous art he is one of the capital’s most desirable dinner party guests.

Colbert has created everything from lobsters sold in his (now closed) Paris namesake store to partnerships with Peanuts and Rolex; he has bucket loads of celebrity followers (Cara, Sienna, Gaga) and he’s big in China.

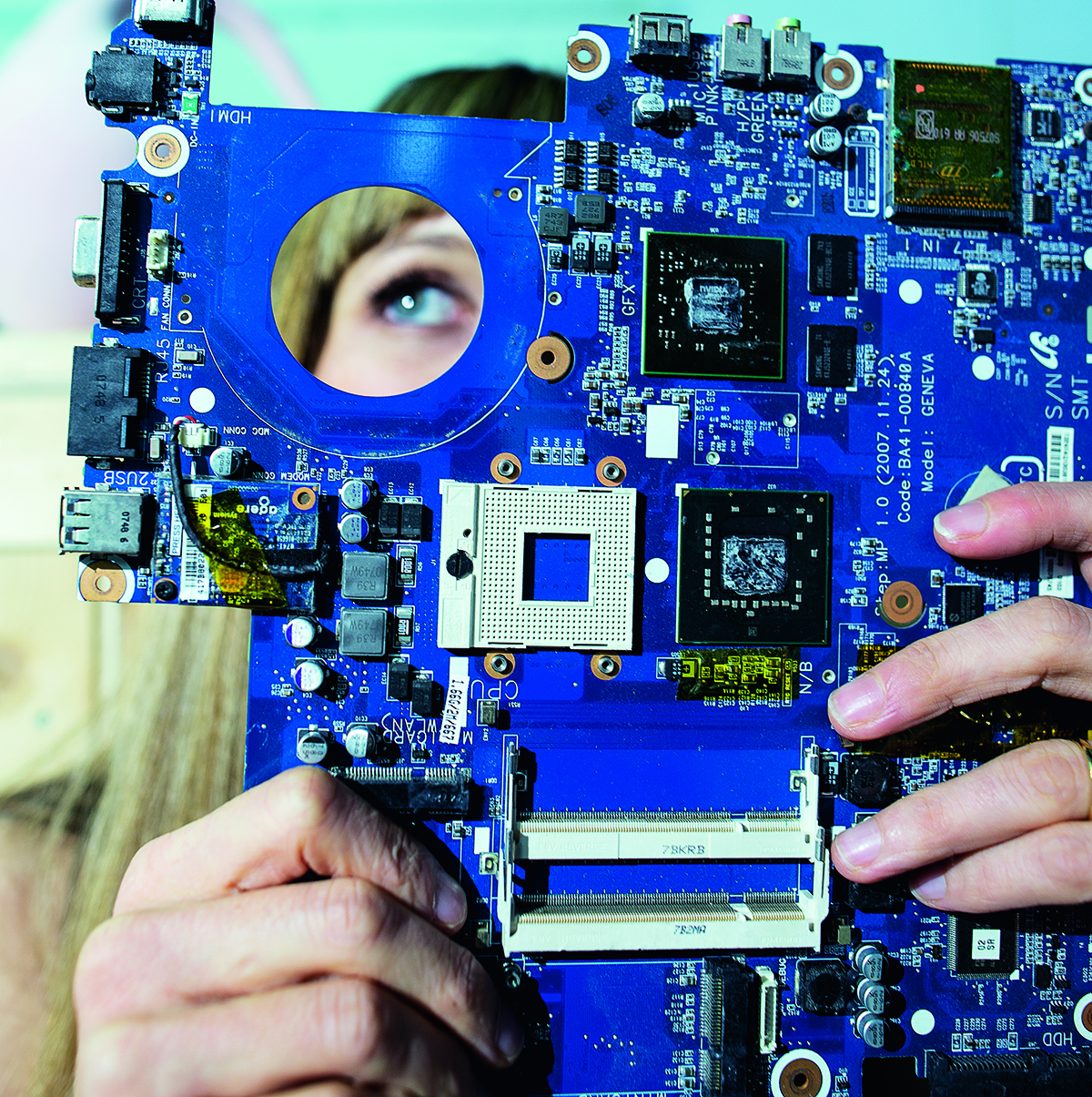

Charlotte with some of her flocked ceramics

But as his latest works show, he is also a proper artist. His ‘Hunt’ paintings, shown recently by the Saatchi Galleries in both London and LA, around each city’s Frieze art fair, are a kind of Raft of the Medusa for contemporary society, riffing on themes around social media’s banal power, swatches from his favoured artists [Dalí, Lichtenstein, Hockney], and providing a poignant commentary on the chaos of contemporary society. They are also vibrant, colourful (as pop art should be) and, frankly, rather beautiful. He thinks of himself as a “neo-pop surrealist”, though a case could be made for him being more pop-impressionist: out of the microcosms of his creations there emerges a whole image of something quite different.

Read more: 6 artists creating new experiential spaces

His wife Charlotte, meanwhile, has created her own artistic world, one which shocks and smiles at the same time. Youthful, photogenic, and with enough wit not to take themselves entirely seriously, the Colberts may just be among the most interesting artists to emerge from Britain in the last decade. And you feel their whole future may just be ahead of them.

Philip Colbert

LUX: How would you describe yourself ?

Philip Colbert: I’m someone who’s trying to create a world. I started out creating a sort of art brand, with artworks and furniture and was, in a way, trying to expand what the idea of art was beyond painting. But recently I’ve come back to painting in a big way and I think fundamentally my journey is about just trying to make my own sort of artistic world. The lobster alter-ego is really an articulation of my artistic persona.

LUX: Why a lobster?

Philip Colbert: I’ve always been into symbols. The lobster was a symbol of surrealism for a lot of surrealist poets and Dalí as well. I like the idea of bringing it to life and taking it on a journey.

Philip Colbert with his iconic lobster alter-ego

LUX: What is art about, for you?

Philip Colbert: The simple essence of art is human freedom, and pushing the creativity that we have. And if you push freedom forward and create more, you push reality and create more freedom for art. There’s something I like about taking the idea of art and trying to inject it with new energy and a new sense of possibility.

LUX: Should artworks be beautiful?

Philip Colbert: It’s an important part of communicating, to understand visual language. A cornerstone of my art is to try and be very positive and use primary colours and really radiate a sort of energy from my works. Even though they may still have a sort of darker undertone, I still like to give them the essence of a sunflower.

‘Untitled II’ (2018) from Philip Colbert’s ‘Hunt Paintings’ series

LUX: Can you talk about ‘The Hunt’ series and how your work has developed?

Philip Colbert: ‘The Hunt’ paintings are important for me. I have been engaging with the idea of contemporary culture and the mass saturation of images and the internet. At the same time I’m still having a conversation with painting. The Old Masters are such a powerful part of art history and I like the idea of making my contemporary Pop culture paintings to be informed by and in conversation with them.

Read more: 6 questions with art collector Kelly Ying

LUX: Symbols from painters – how do you choose them?

Philip Colbert: Well, I was really drawn to elevated images, such as in history painting, with heroic battle depictions by artists such as Rubens. I wanted to underpin the violence of contemporary culture and use the analogy of a more traditional battle scene, to structure it like an Instagram feed. We consume so much today, and we see so much, we’re aware of so many amazingly escapist ideas juxtaposed with a lot of darker elements, like global warming or political instability. A lot of artists have been exploring abstraction or exploring obsession, but I wanted to capture more of this play of light and dark. I thought that the analogy of the battle scene was a good way to explore these tensions.

Philip at work on ‘Screw Hunt II’ (2018)

LUX: Have you felt pushed back by contemporary art establishments?

Philip Colbert: I think of myself as an outsider in a way, because I studied philosophy and really just developed my own practice. I’m not looking for validation from anyone. I feel that in the art world, people are sometimes groomed to want to please, but I’m much more interested in just connecting to people on a real and direct level.

LUX: Are you here to sell art or create art?

Philip Colbert: One hundred per cent to create art. The sales side of it is obviously an essential part of being able to grow because it allows one to do more, but I’m not deliberately engineering my works to be purely reflective of the market, which is not necessarily a bad thing either – Warhol was very good at mirroring what he felt the system wanted. My paintings are complex and intense and highly saturated, so are not the easiest to sell via Instagram, for example.

LUX: Talk about your use of social media.

Philip Colbert: If I think of my paintings as a reflection of my interaction with contemporary culture, social media are a significant element within that. There are some different strands of my work. I’m really developing a lot of these big history paintings, but also I’ve developed ‘Lobster Land’, a virtual reality world, which is the digital world where my lobster character lives. And in Lobster Land there’s a Lobster Bank, Lobster Coin, there’s a museum. I’m building my own reality there, which is one way of engaging with contemporary technology.

‘Hunt Triptych’ (2018) from the ‘Hunt Paintings’ series

LUX: How did you get started in China?

Philip Colbert: It happened very organically. When I had my first exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, curators from China came along and they featured some of my paintings in a group show in China. That was maybe June last year. It was amazing – I saw a crazy energy in China when I was there. So many people came to the show. It has simply evolved from there.

LUX: What are your influences?

Philip Colbert: There’s very much a ‘celebration of appropriation’ in these paintings. I was putting myself at the centre of the piece –you get the idea, it’s like my character is the narrator of the painting but then there’s art history effectively having a sort of ‘battle dialogue’ with this voice. This sort of dialogue is present in an artist’s mind when they’re creating an artwork. There’s the idea of place and time in the relationships to other philosophies and ideas within art, so by putting them into a battle sequence, it represents my own philosophy battling with other ideas and also being able to present a much bigger holistic idea, to create an orchestrated, ‘multi-philosophied’ painting. I’ve referenced loads of things deliberately. Léger was, for me, a very important proto-Pop thinker/painter, and his work was influential on people like Lichtenstein, who often even referred to Léger in the bottom corners of his paintings. My paintings are an evolution of Pop art – I have those references while I’m still playing with abstraction and different varieties of painting styles within a single painting.

LUX: This sounds more like it’s from inside someone’s mind rather than culture?

Philip Colbert: Yeah, I think of the paintings as like mind-maps in a way. I was really interested in ideas of art, so that’s why I like to use preconceived ideas because for me they are language. I could create my own characters but I wanted to use branded ideas that people could understand. So, when people look at the paintings, they will immediately understand ‘That’s Van Gogh’, or ‘that’s a Gucci handbag’. It’s using things that are already loaded with meaning.

Philip and Charlotte Colbert

LUX: Is it strange not coming from a family of artists?

Philip Colbert: No, I don’t think so. Some people’s parents are artists and they follow suit and are inspired by a world they’ve already been presented with. For me, I was always just connected with art and so it was always the language I was immediately connected with. As you know, I went into making clothing first, but I wasn’t making clothing to be a fashion designer, I was making clothing and thinking about artwork. I was more interested in this idea of ‘wearable art’ and trying to use the idea of a brand as a vehicle for art.

Read more: Maryam Eisler in conversation with Kenny Scharf

LUX: What plans do you have for the future?

Philip Colbert: Well, I have an exhibition in Shanghai at the end of June, then I have two shows in Hong Kong, a show in a museum in South Korea, and then another in Moscow in September in a multi-media art museum.

LUX: Do you and Charlotte collaborate?

Philip Colbert: Well, we’re married, so we inevitably interact and have an influence on each other’s work. We have quite a different aesthetic and even though we’re both interested in a lot of the same things, our end picture is very different, which is nice. But I think we both understand each other’s DNA, so we can help each other.

Charlotte Colbert with ‘Self Portrait in Lucian Freud’s studio’ (2018) from her ‘Screen Portrait’ series

Charlotte Colbert

LUX: Tell us about your photography.

Charlotte Colbert: I have done a couple of series. I started in 2013 with ‘A Day at Home’. It correlated the madness of the writer and the madness of the housewife in this domestic space that was both a prison and open to the landscapes of the imagination. It sort of chronicled the porousness of the world around the woman in a decrepit house in East London. We kept shooting as the place was being demolished, so we were getting layers of that story-telling within the building itself. Then I worked on ‘Ordinary Madness’ [2016], which was about our relationship to the digital age. The idea was that we expected aliens to come from outer space and somehow conquer us. But, little by little, we are becoming the cyborg, and technology is being absorbed into our bodies and changing the fabric of our being until we’ve become a new sort of human.

LUX: The video sculptures, ‘Screen Portraits’, are they bronzes?

Charlotte Colbert: No, they’re made of Corten steel. The first one was done for the Korea Institute. I came across this beautiful but heart-breaking story of a South Korean woman, Lee Soon-Kyu, who was 79 when I met her. She was pregnant when the Korean War started in 1950, but was separated from her husband who ended up in the north. She was able to meet him many years later, and went to North Korea with her son, who was then 65, to see him for the last time. It seemed fitting to do her portrait at this moment in her life, after she’d been in this Cold War kind of narrative for decades. She had to stay very still with just one light on her face. The filming of the sculpture was an extraordinary moment.

LUX: The one with a nuclear explosion, tell us about that.

Charlotte Colbert: That’s a piece called Disassociation. It’s a self-portrait. The eyes and the face are very much at peace and the head contains the nuclear explosion. I made it when I was seven months pregnant, at a time when you feel disconnected from the world around you. But I feel that in some ways it’s like an extreme version of everyone’s relationship to the world.

LUX: Neighbouring studios with Philip – how does that work?

Charlotte Colbert: Funnily enough, we’ve done loads of stuff together and I think in some way, we do look at each other’s works and comment on them, but our worlds definitely haven’t fused. I feel like both of us have pushed the identities really as defined against each other.

LUX: The studio, it seems very serene.

Charlotte Colbert: It’s amazing but there’s a lot of interesting characters around, and the building’s quite fun and it’s got all these layers of history. I think at one point it was a kennels, so there were dogs, now there’s more little mice. It’s a really amazing location – we’re so lucky.

Find out more: philipcolbert.com and charlottecolbert.com

This article was originally published in the Summer 19 Issue.