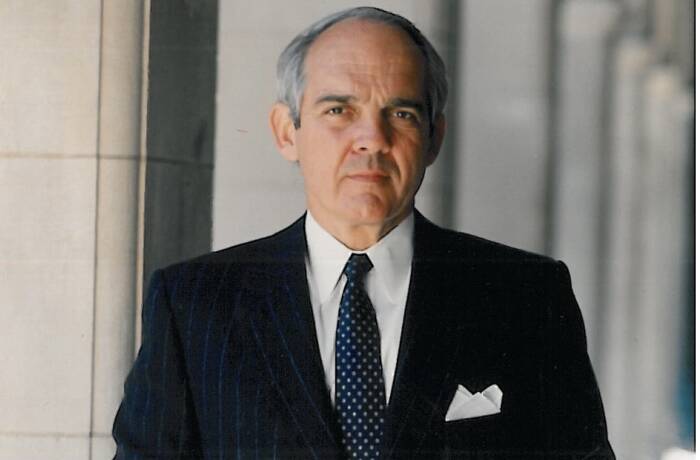

A soirée to celebrate Cristal and art in London. Left to right: Lorna Mourad, Jennifer Chamandi Boghossian, Rob Boghossian, Ege Gürmeriçliler, Darius Sanai, Laurent Ganem, Maria Sukkar, Frédéric Rouzaud, Anne-Pierre d’Albis-Ganem, Nadim Mourad, Richard Billett, Samantha Welsh and Malek Sukkar, with an Anish Kapoor artwork on the wall

Louis Roederer, maker of Cristal and other celebrated champagnes, has long led the way in environmentally conscious winemaking, using biodynamic and organic techniques. CEO Frédéric Rouzaud has also brought his passion for art photography to the fore with a series of initiatives supporting photographers around related themes. Now the champagne house champions massal selection, an expensive way of allowing natural selection to create diversity in the vineyard and complexity of taste. LUX visits the vineyards in France and speaks with Chief Winemaker Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon about how working with nature is the hardest – and most rewarding – labour of all.

Frédéric Rouzaud, CEO of Cristal maker Louis Roederer, commissioned artistic photographer Jean-Charles Gutner to create a series of images based on the leaves produced by grapevines of different varieties grown using massal selection

A Conversation with Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon of Louis Roederer about how working with nature stimulates biodiversity, conserves the soil – and makes the greatest wines

LUX: How long does it take someone to gain the necessary expertise to identify the best vines in a vineyard and to curate a massal selection?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: It’s not one person only. Louis Roederer’s In Vinifera Aeternitas project was launched in 2002 and includes a group of experts: Professor Jean-Michel Boursiquot from Montpellier, probably the most talented ampelograph [one who identifies and classifies grapevines] in the world; Lilian Bérillon – a nursery owner specialising in massal selection of the best domaines all over the world – and his team; and our own vineyard team.

Jean-Charles Gutner, creator of Solar Panel, Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon and Frédéric Rouzaud

LUX: I read that for massal selection at Louis Roederer, you say the best bunches are small or medium in size, weighing 100g to 110g and of perfect quality. What makes a perfect grape?

JBL: ’Perfect quality’ does need explanation. In our quest, it means a combination of clean fruit – disease-free through thicker skins and good aeration – and homogeneous phenolic ripeness in berries of the same cluster, avoiding green or overripe berries that could create vegetal or cooked-fruit notes.

LUX: Louis Roederer is also opening up new possibilities by growing young vines without American rootstocks, that is, pre-phylloxera style [phylloxera destroyed many European vineyards from the 19th century onwards, a crisis combatted by grafting European vines onto phylloxera-tolerant American vine rootstock]. How is it working?

JBL: So far we must admit we have had little success in this experiment. Most of the vines have now been infected by phylloxera. Only very few are still alive. We follow them to see if they are resilient or not. We are also working on different clones of rootstocks.

A leaf from a Chardonnay vine from Avize, a village in the Cotes des Blancs, the hillsides renowned for producing the greatest Chardonnay wine in the region

LUX: What do you find most exciting about massal selection?

JBL: The most exciting thing is to witness the huge biodiversity within Pinot Noir. There can be up to 10-15 days difference in the ripening process, which is amazing.

Read more: Two key players in British fashion raise the game for personal shopping

LUX: You have said of massal selection that you had to regenerate the plant material and recover some of the singularity of the Louis Roederer style through massal selection. Does this affect the taste?

JBL: The first goal is to regenerate virus-free vines for a strong ecosystem, through the diversity of individual vines replanted with pools of a minimum of 30 individuals. The second goal is to protect our unique legacy: we have chosen our oldest plots of vines, pre-1960, to select our massal vines. Those vines now make Cristal rosé, but before 1974 they were the heart of our Cristal domaine from its inception in 1876. Therefore, we believe that by regenerating this material, we are also on a crusade in the name of taste.

Louis Roederer uses sustainable practices, including massal selection, to work with nature and achieve the most accurate expression of its unique terroirs

LUX: In massal selection, the talk is of going back in time, to recultivating the uniqueness that wine used to have. But has wine always tasted the same, or did it taste different, say, in the pre-phylloxera era, and if so, how?

JBL: The idea is not to go back in time. Our In Vinifera Aeternitas project aims to restore the diversity of vines, which will reinforce the natural resilience of our production and ecosystem.

LUX: How does Louis Roederer’s process of massal selection differ to competitors?

JBL: It is our own unique legacy, therefore it cannot be compared to anyone else’s. We have also elevated the idea in an artistic dimension, such as when the photographer Jean-Charles Gutner teamed up with the In Vinifera Aeternitas project to craft unique pictures of the biodiversity of our ecosystem in his Solar Panel series.

The making of leaf images, from the Solar Panel series, by Jean-Charles Gutner

LUX: How has massal selection changed Louis Roederer’s character as a company?

JBL: It has not changed our character, which has always been to secure our family-owned business for the next generations. In Vinifera Aeternitas is one part – the biodiversity and taste part – of a higher ambition, which includes many other aspects of permaculture, like reducing our footprint through responsible soil, water and energy use. Hence our family motto: “hand in hand with nature”.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

LUX: What led the Rouzaud family and yourself towards a climate-conscious future?

JBL: The key was probably our meeting with Bill Mollisson, the father of permaculture, in Tasmania in early 1990s. It became obvious to all of us that we had to secure the future by introducing the philosophy of permaculture – working organically with nature not against it, considering craftsmanship and social aspect, biodiversity, low energy use, rotation, the balance of tradition and innovation.

“Perfect quality” black grapes from the vineyards are used for propagation in Louis Roederer’s massal selection

LUX: What is the future of massal selection? Will it ever take over from clonal selection, which ensures uniformity and consistent quality?

JBL: Unlike clonal selection, our massal selection is a permanent quest. Every year we must reselect new individual plants and add some individuals of different origins for propagation. It must be a permanent process if you want to restore biodiversity, as vines adapt and mutate under abiotic factors, such as water and soil.

Read more: Lebanese couturier Elie Saab on designing beauty

LUX: What is the future of massal selection? Will it ever take over from clonal selection, which ensures uniformity and consistent quality?

JBL: Unlike clonal selection, our massal selection is a permanent quest. Every year we must reselect new individual plants and add some individuals of different origins for propagation. It must be a permanent process if you want to restore biodiversity, as vines adapt and mutate under abiotic factors, such as water and soil.

Gutner’s leaf images champion the biodiversity of the Louis Roederer vines

LUX: How many people are involved with massal selection at Louis Roederer?

JBL: All our vineyard team is involved: 50 to 60 people!

LUX: Does massal selection make economic, as well as environmental sense?

JBL: Not in the short term, but we are family owned and take all our decisions for the long term.

Interview by Isabella Fergusson