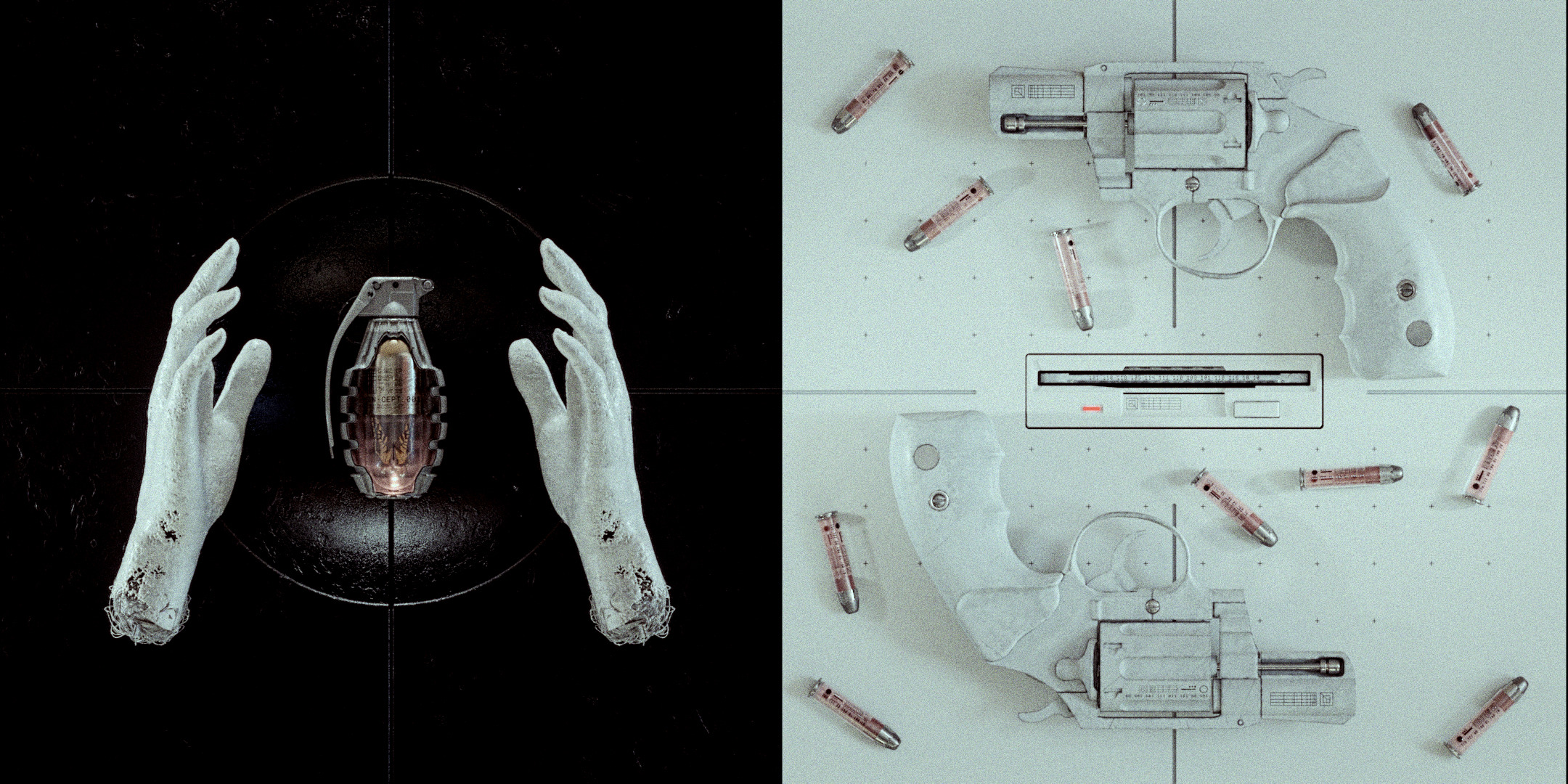

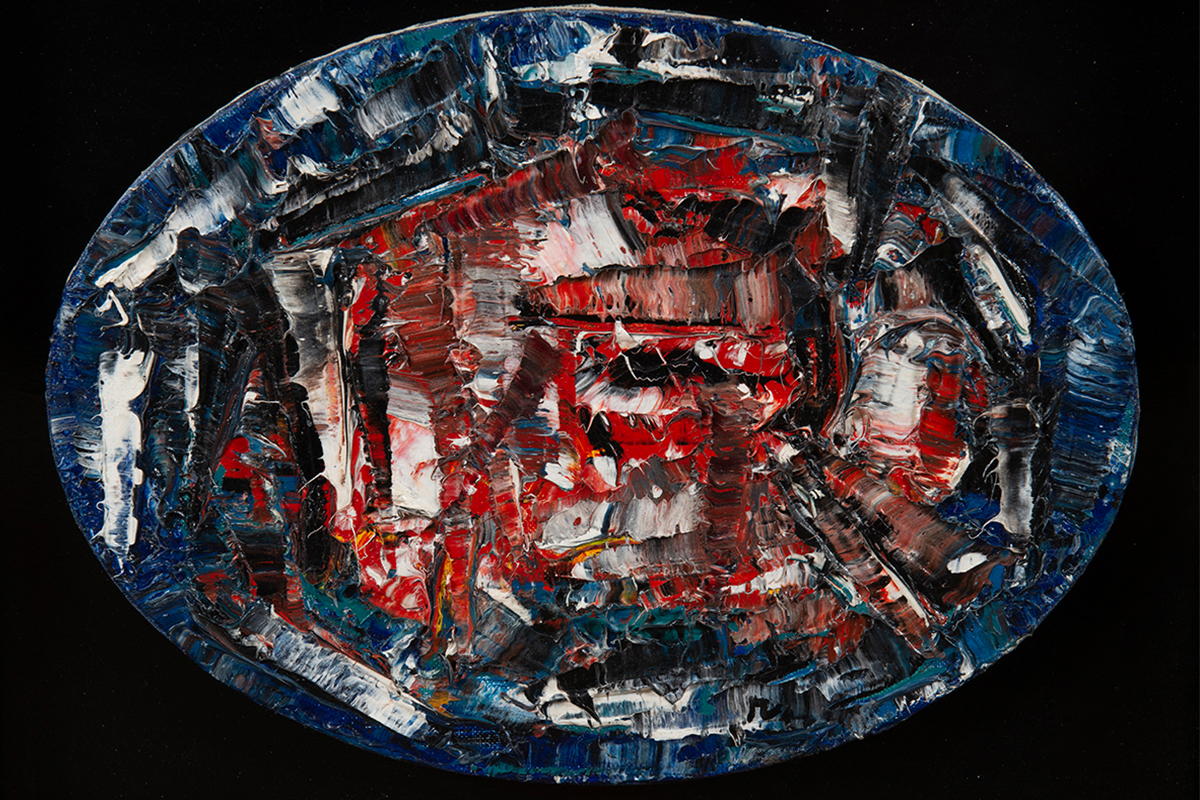

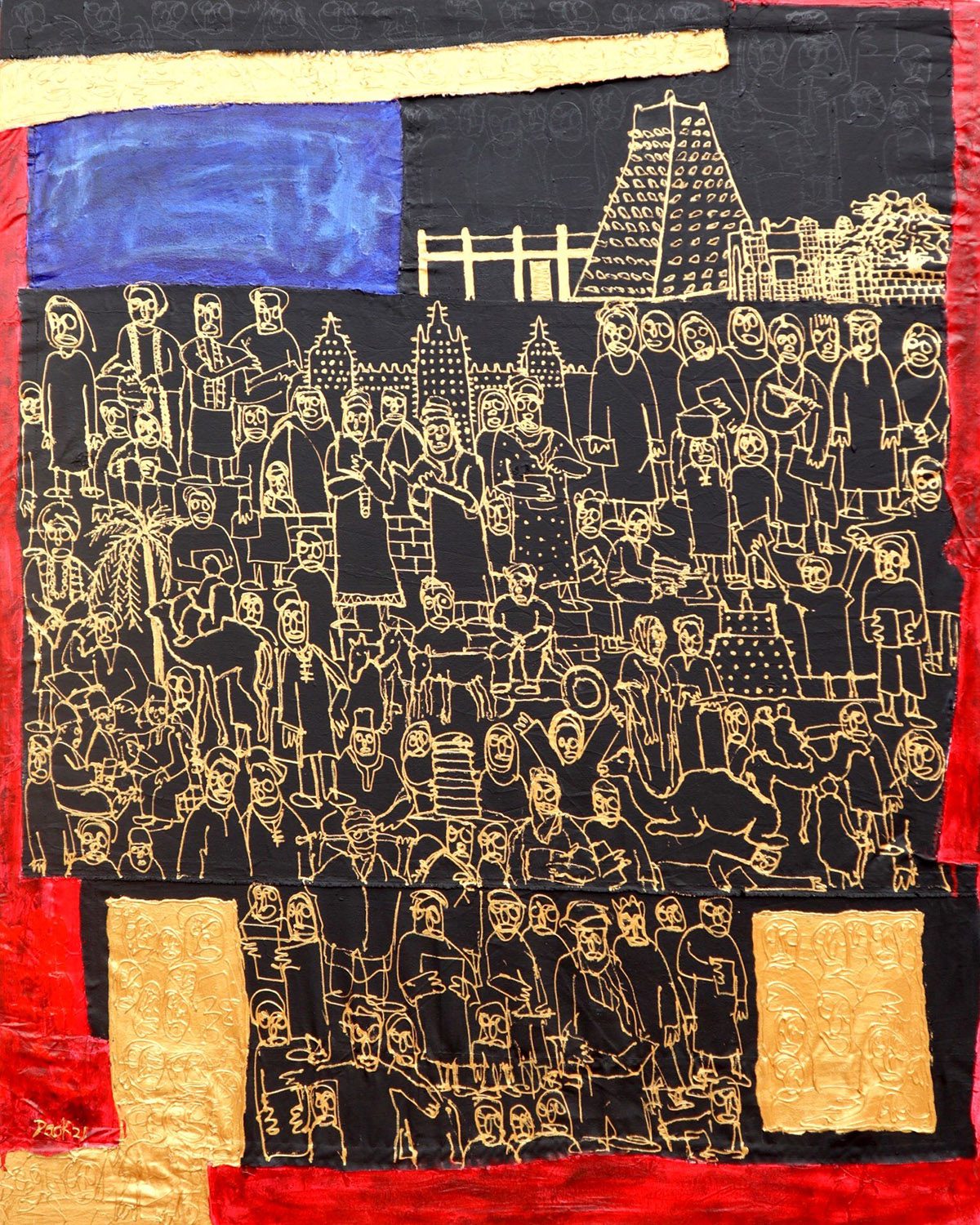

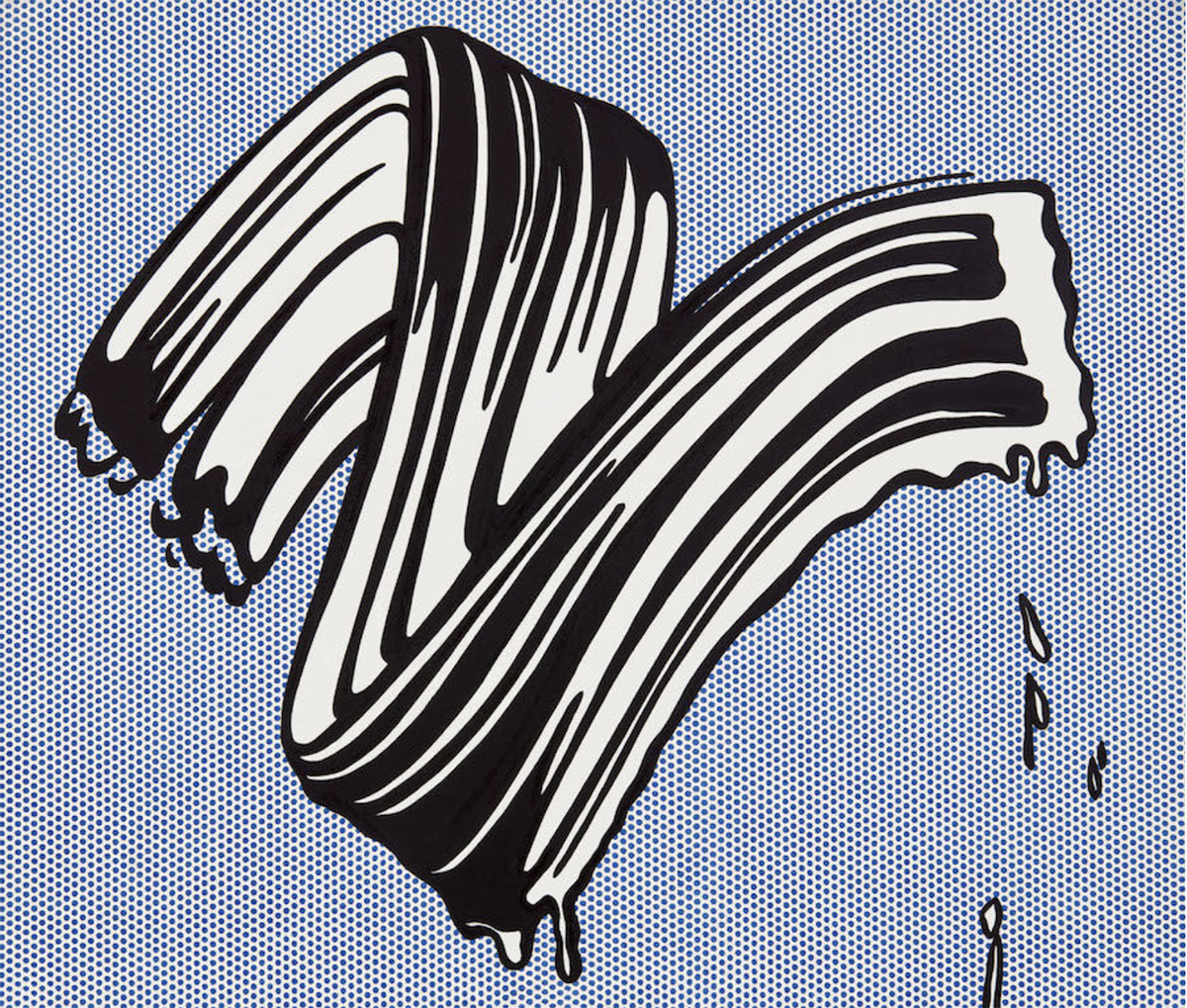

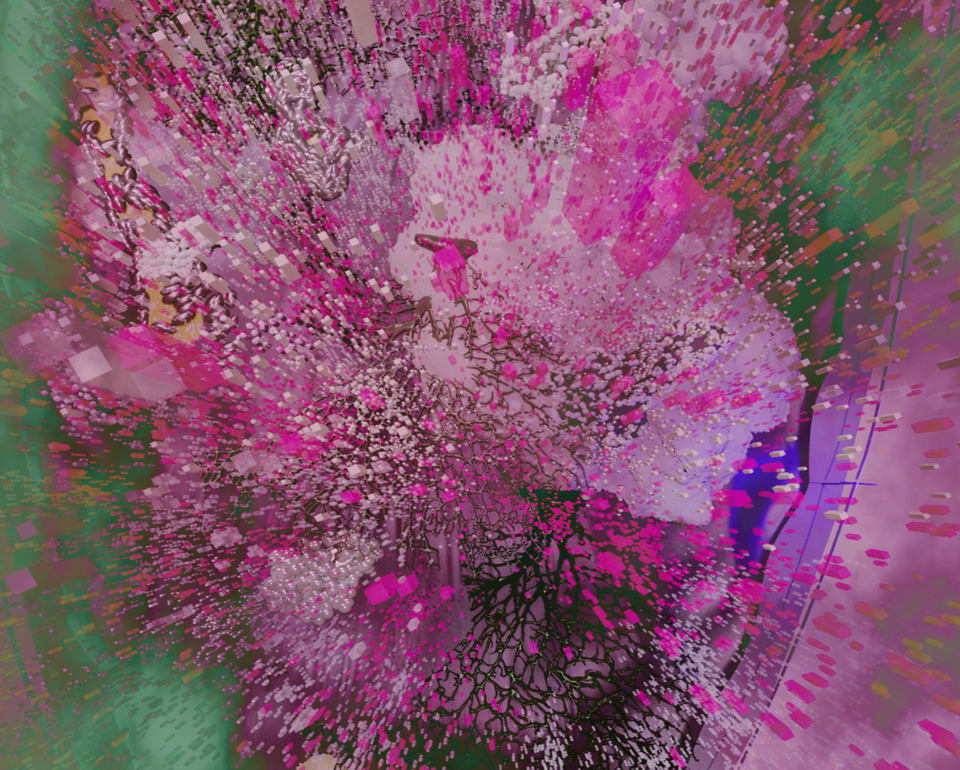

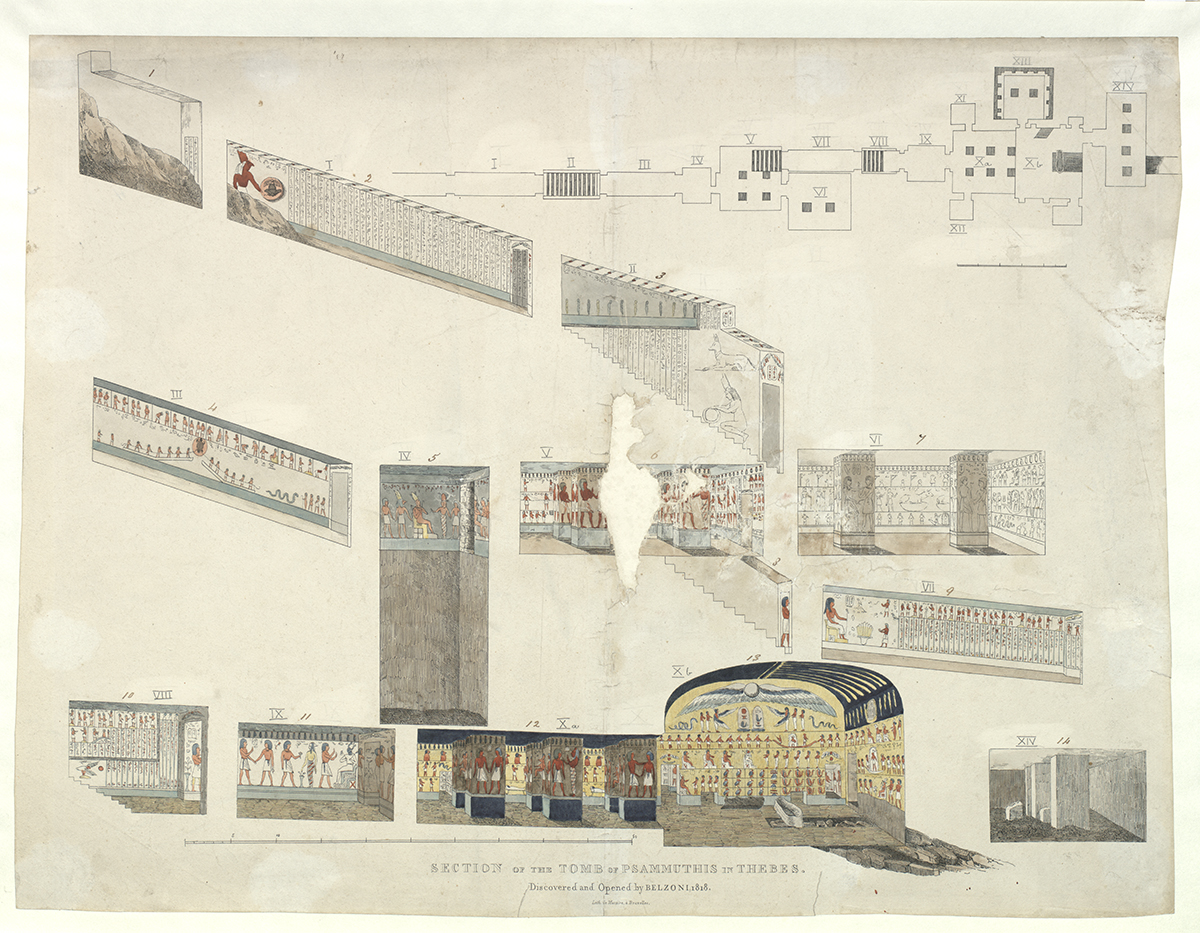

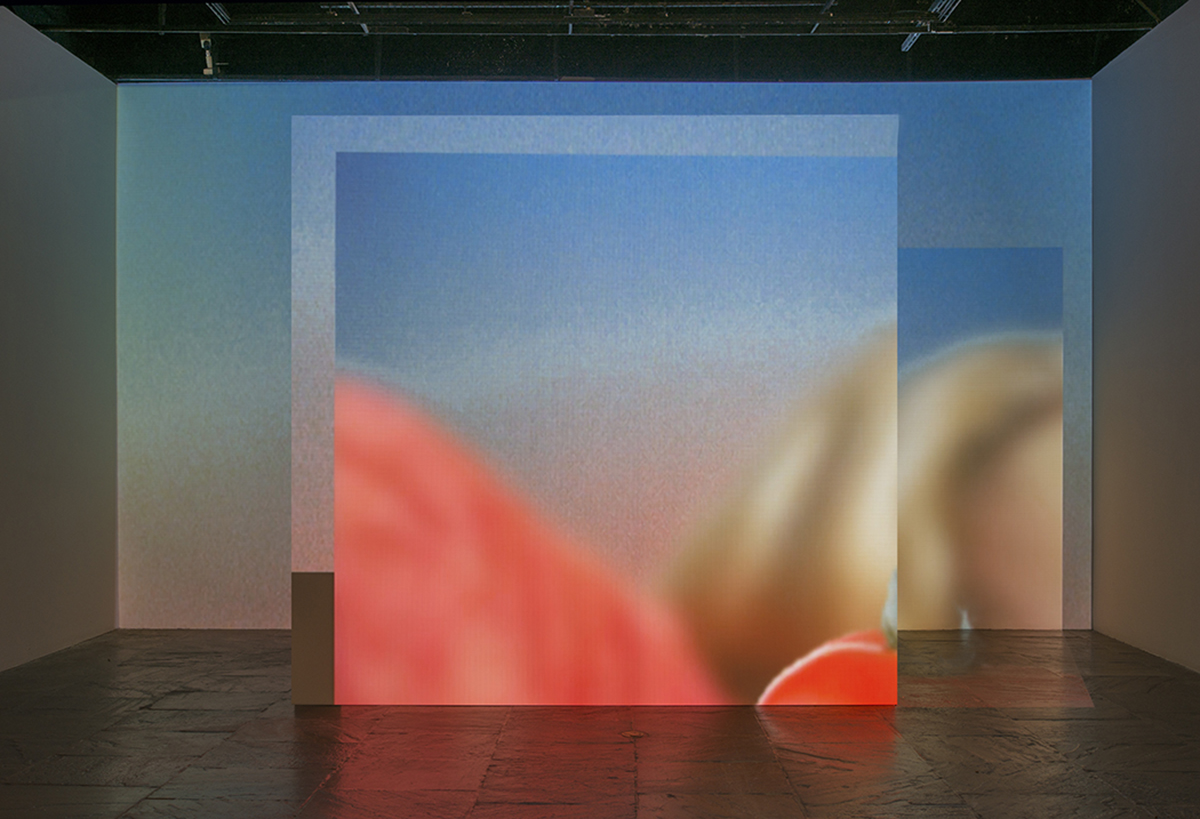

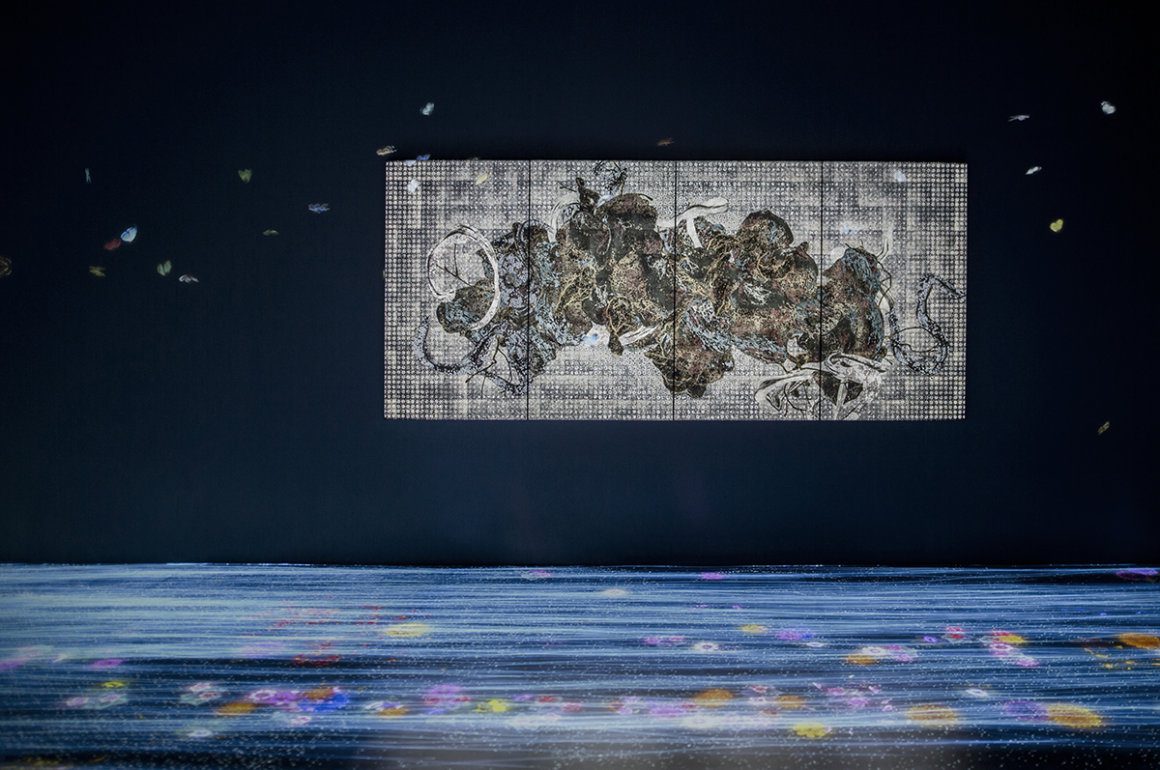

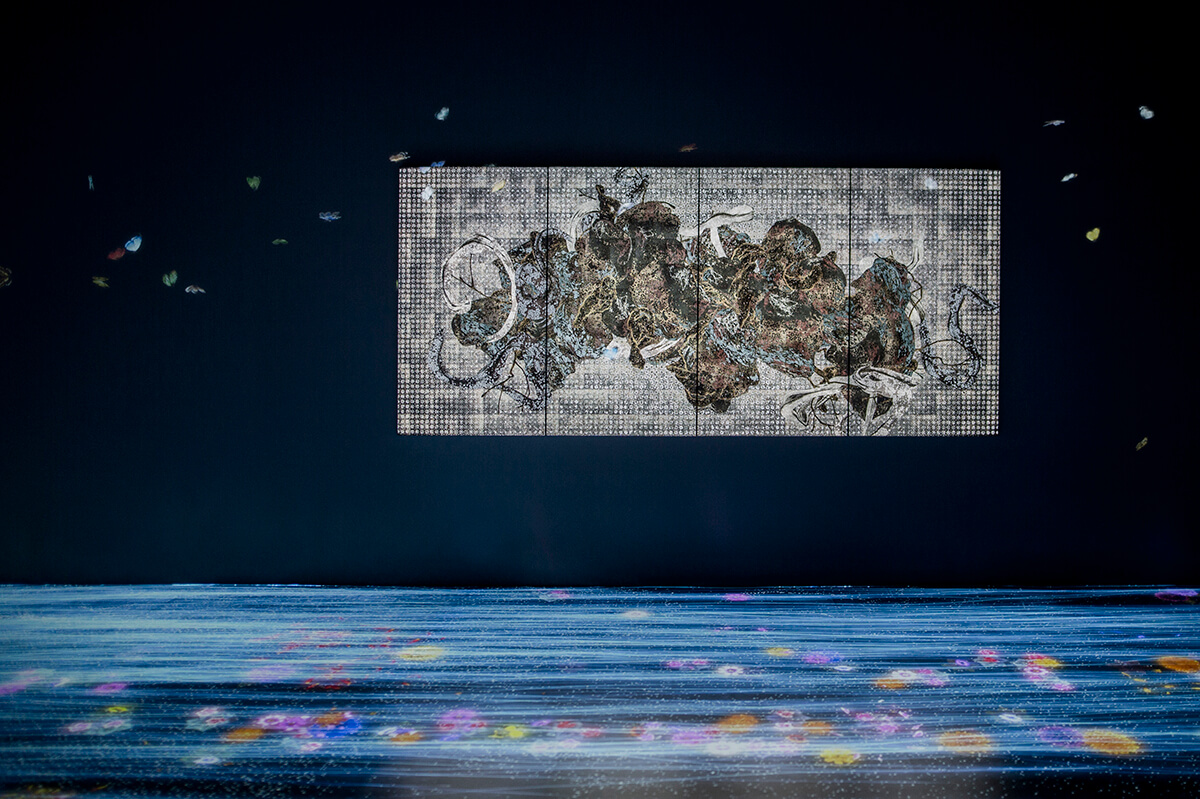

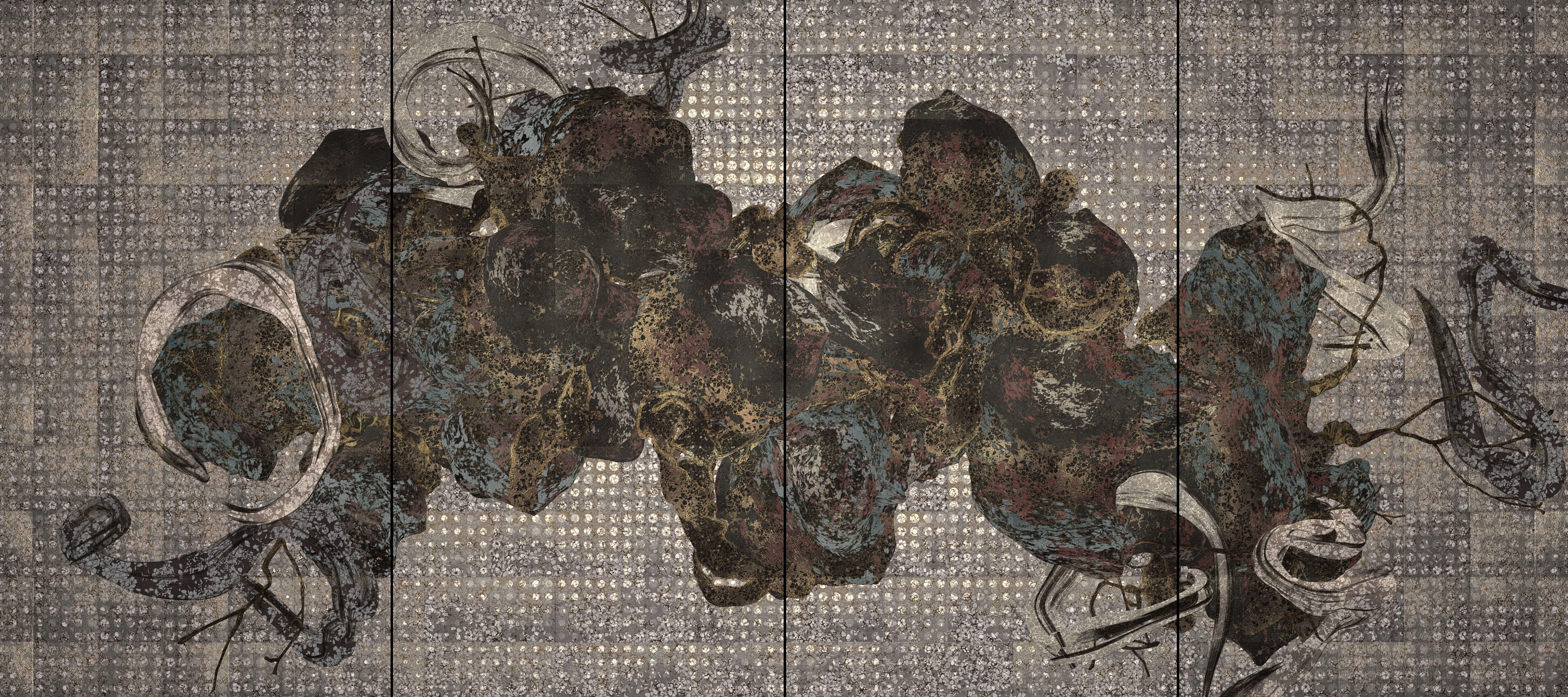

A collage of works from Ash Thorp’s ‘Nascent’ series (2022)

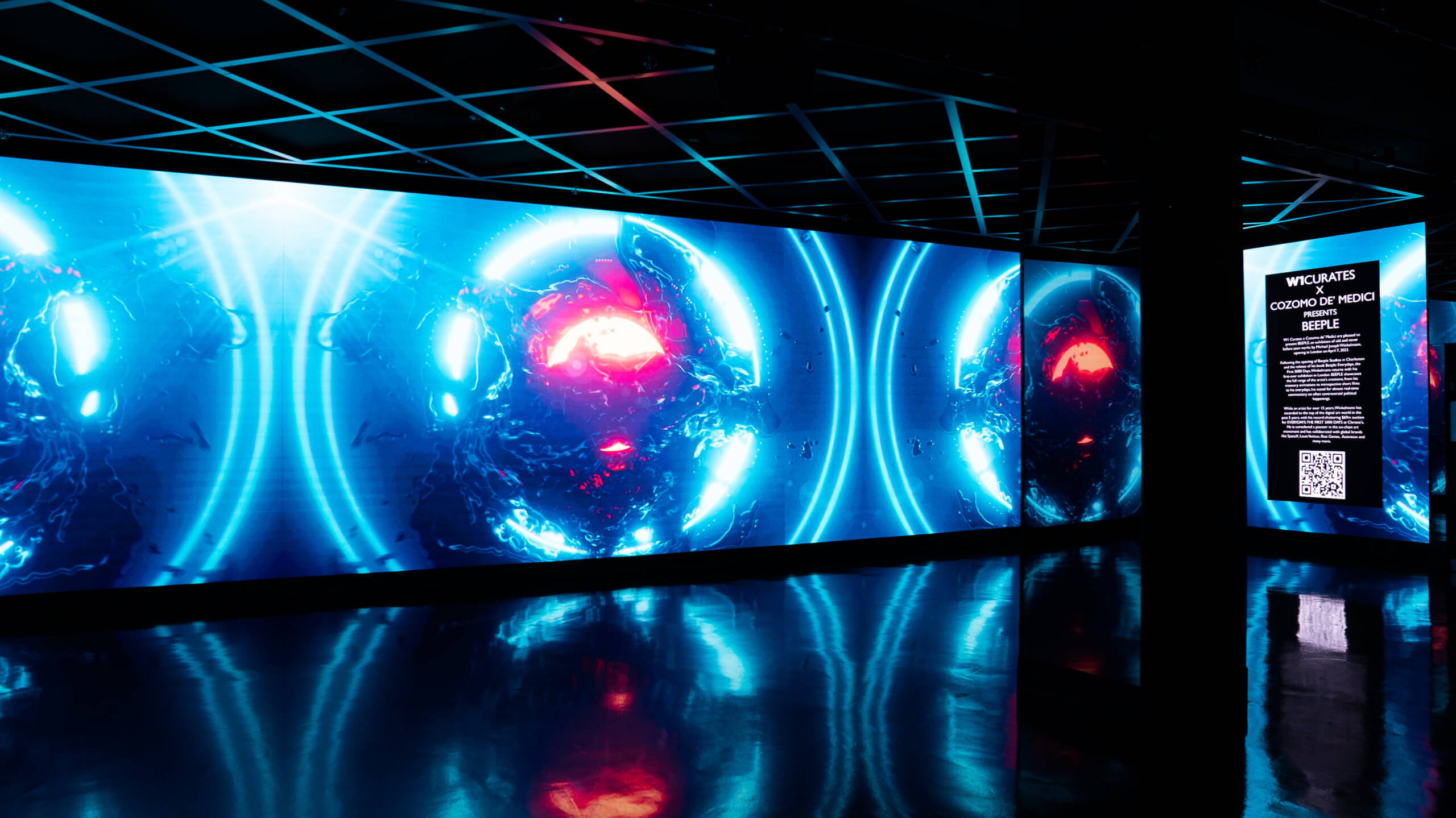

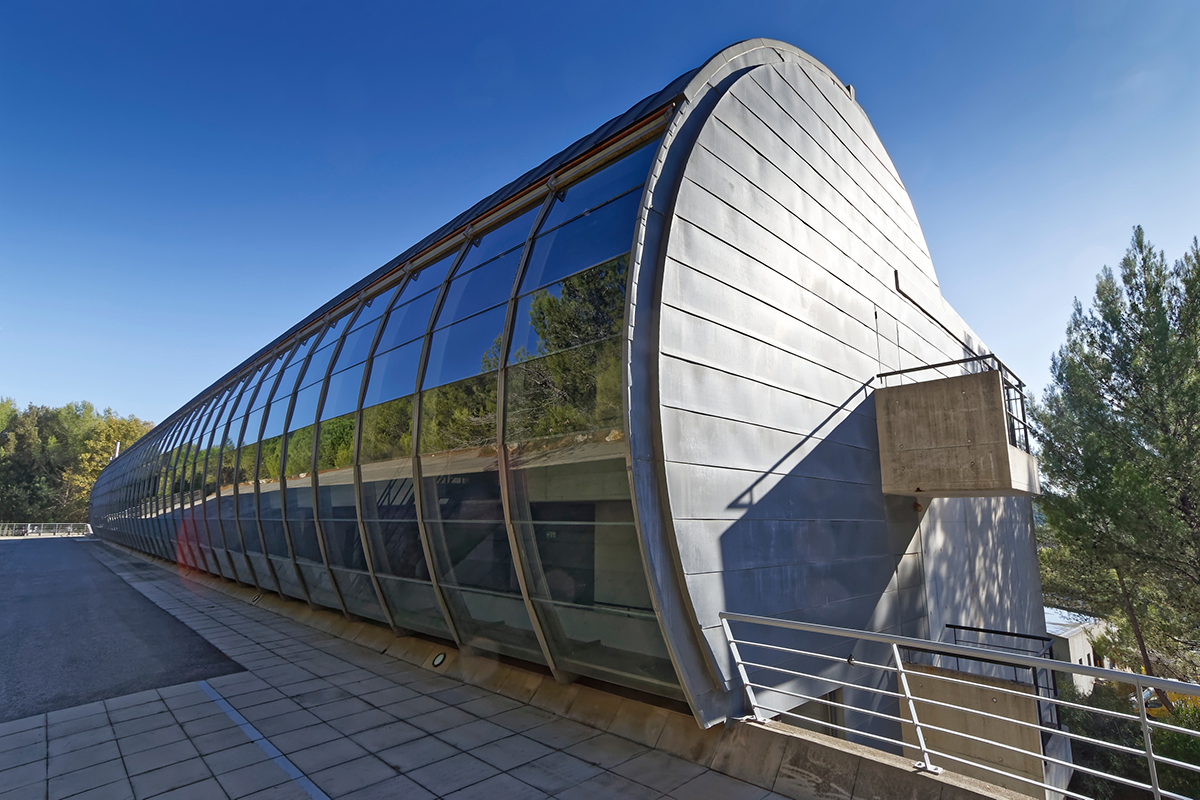

California-based Ash Thorp is a digital artist who creates complex, conceptual artworks. LUX met him recently at a solo show of his works on the giant screens of the W1 Curates space in Soho, London, during the Frieze Art Fair, an exhibition supported by uber-creative super luxury watch brand Richard Mille. We caught up with him in his studio in San Diego, southern California, to speak about past projects, future plans, and the tide of digital art.

LUX: You first started with traditional art and then transferred into digital art. Does digital art creates more of a dialogue between the art and viewer than traditional art?

Ash Thorp: All forms of art serve diverse purposes and employ their own unique mechanisms to engage viewers. For me, the key distinction with the dialogue digital art creates is its symbiotic relationship with the advancement of humanity. Technology plays a pivotal role in shaping our world in this current era and digital art is intricately linked to it. It mirrors the current state of our society and reflects our ongoing transformation as a species. This connection introduces multifaceted levels of engagement, contributing utility and value, not just to the artist but also to the audience.

LUX: You have mentioned a 80/20 rule in our discussions about your art. Can you elaborate this?

AT: I strive to supply 80% of the context and intention of the artwork, and then invite you, the viewer, to extrapolate and complete the remaining 20% based on your own narration. The hope of this artistic intention is to prompt you to apply your own personal values, make predictions, form estimations, and view the piece through your unique lens. My role is merely to provide an initial platform upon which you can create further dialogue. I believe that art is most potent when it transforms into a conversation between the creator’s intent and the viewer’s interpretation by provoking questions, stimulating thoughts, and evoking emotions.

I welcome and value this engagement with my work, urging viewers to explore further and contemplate the underlying themes and ideas that elicit their thoughts and feelings.

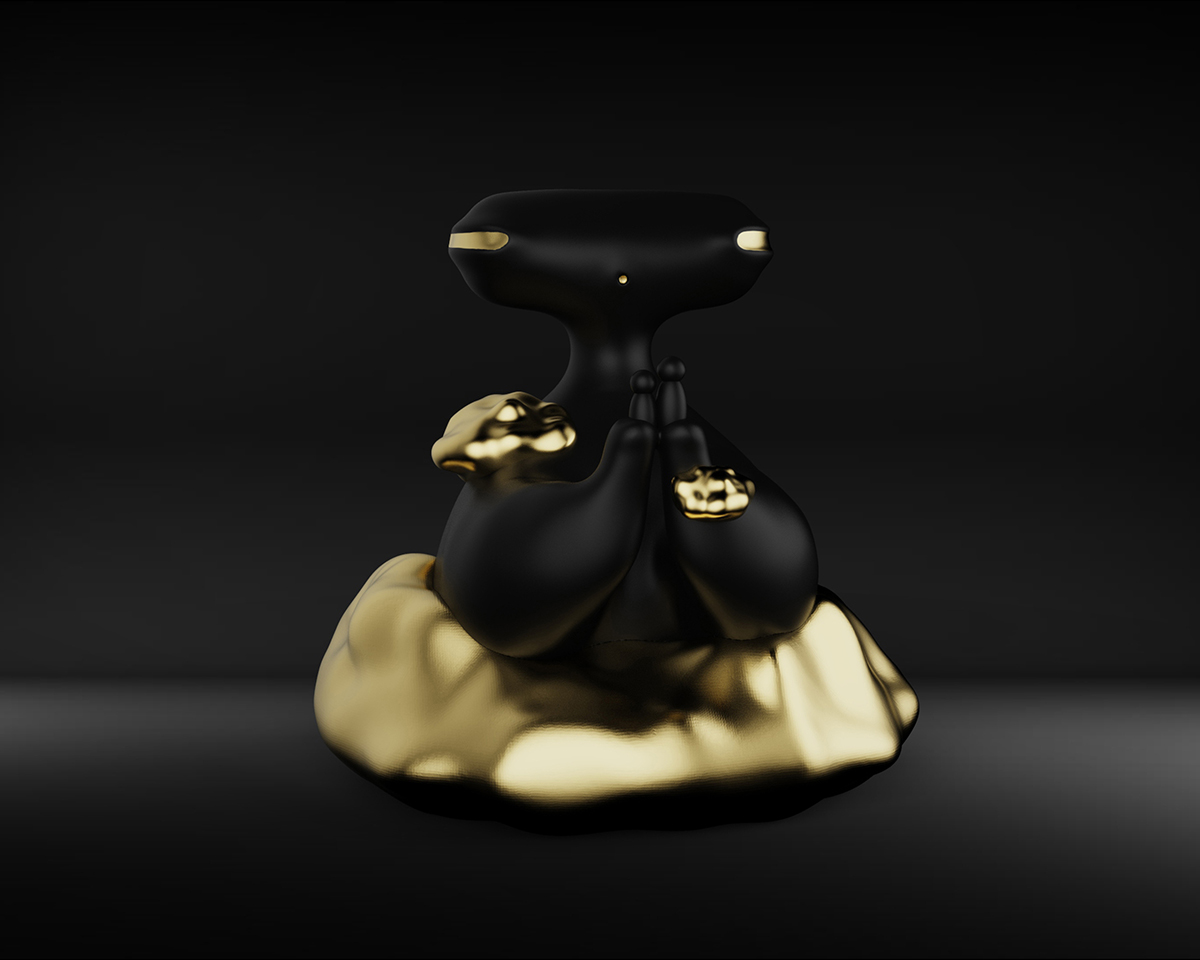

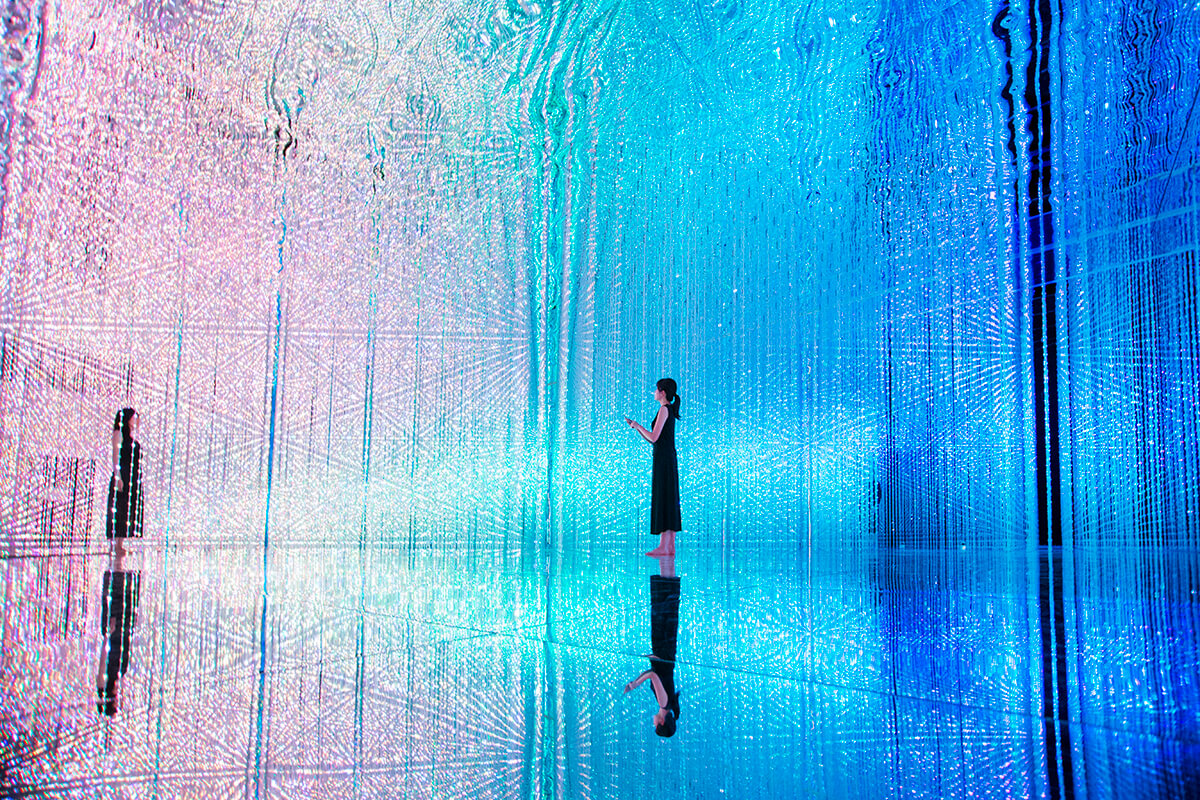

The Happiness Pills from Thorp’s ‘Nascent’ Series’

LUX: Is training in traditional art fundamental to the practice of digital art?

AT: I believe in order to develop a profound understanding of any chosen pursuit, it is important to understand its origin and then dedicate yourself to its further exploration. This journey of self-discovery involves understanding one’s place in the artistic landscape, appreciating the work of those who came before, and gaining insights into how they expressed themselves. My early exposure to the traditional fundamentals of art during my formative years provided invaluable insights into the development of my current artistic practice. Absorbing as much knowledge as possible from all pathways will help cultivate a diverse and enriched mind, thereby benefitting both the individual and the broader world.

LUX: AI is, of course, the buzz topic of the current moment. How do you think it will shape our view of digital art?

AT: The ever-present allure of being introduced to anything new and technologically significant is a phenomenon that can be very captivating; in the realm of art currently, this is the integration of AI. While AI can provide an alluring spectrum of possibilities, allowing it to assume a dominant role in the creative process doesn’t evoke the same intrinsic value for me. I believe the essence of artistry is found in the triumphs and pitfalls, of creating it, and being able to experience the pure joy and raw emotions resulting from personal exploration and discovery.

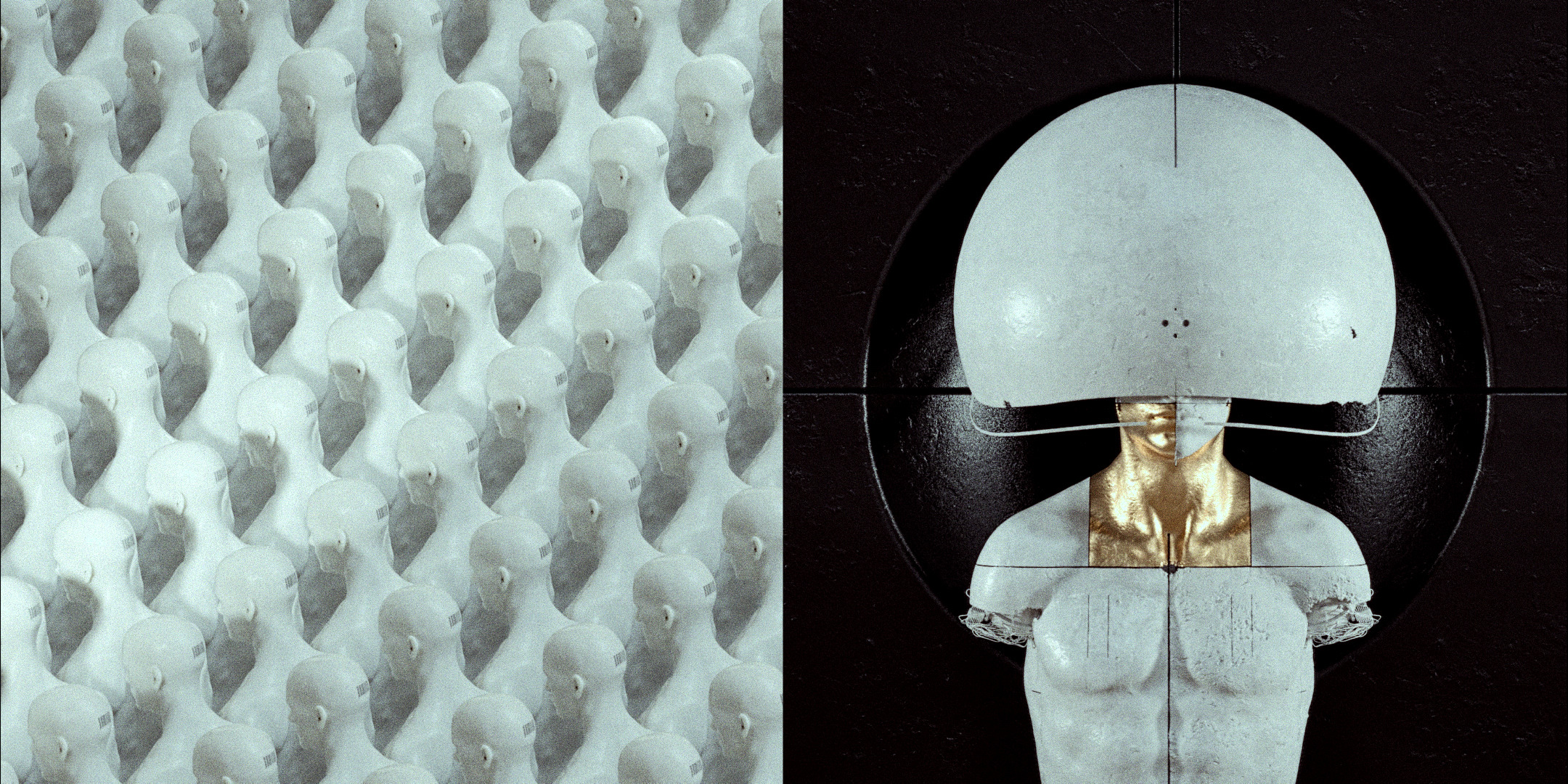

Balaclava by Ash Thorp from the ‘Nascent’ series

LUX: Do you feel that the AI-employed art is still yours?

AT: The ethical considerations surrounding the use of AI, particularly in generating content, hinge on the specifics of the training model and the group of data utilized. Before AI, plagiarism was more easily tracked back to a distinct source and straightforwardly deemed a transgression in any form of communication. Now we seem to be entering a new era without transparency and a range of polarizing answers to this question. The implications of this ongoing debate will profoundly change the art industry and the world. Ultimately, our actions should not deprive oneself or others of an authentic mind and voice.

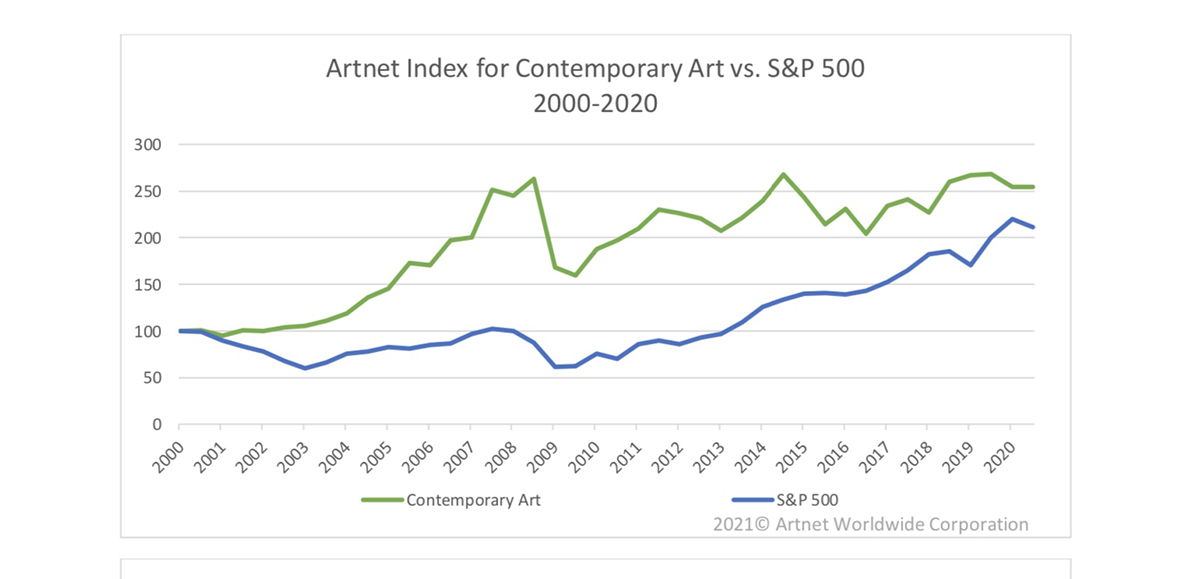

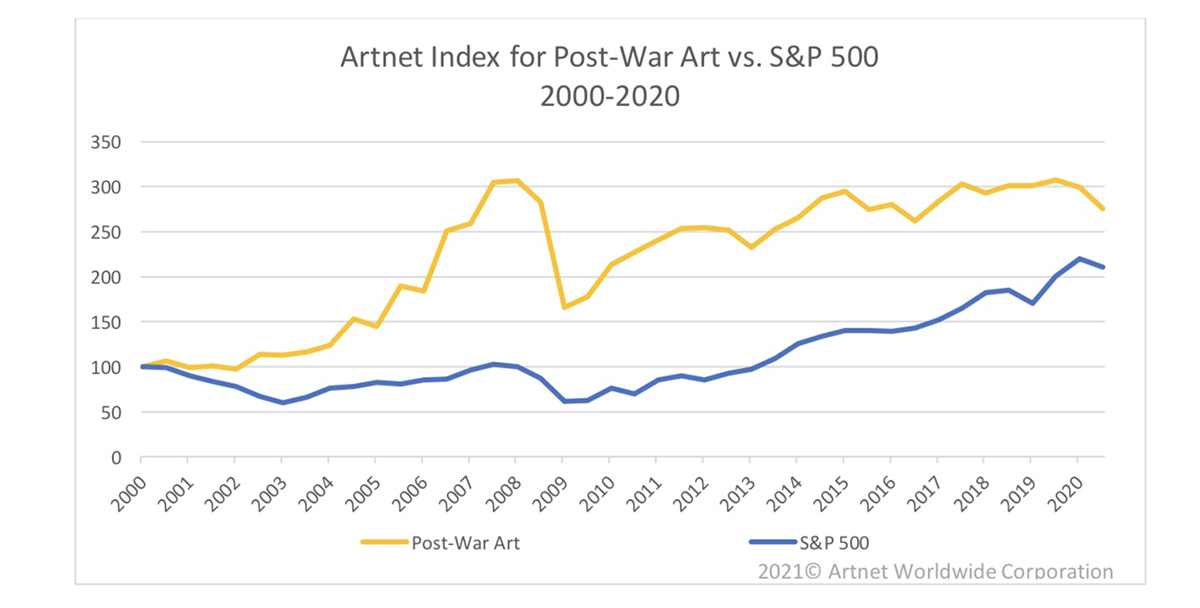

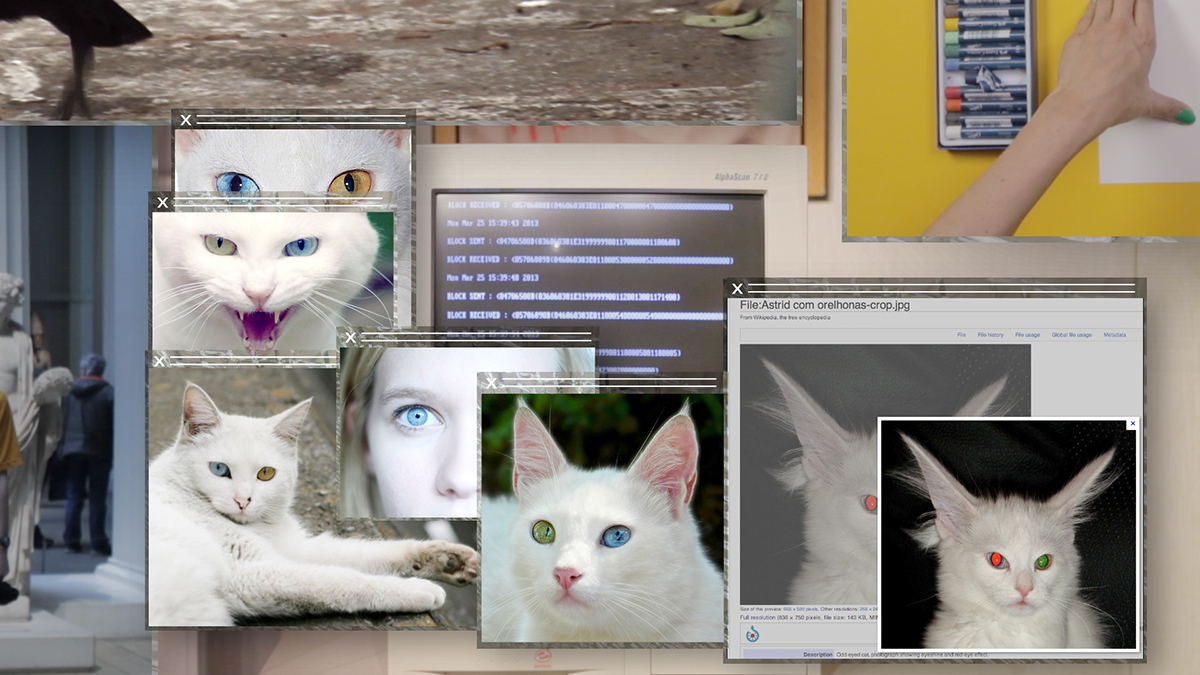

LUX: In terms of collecting and selling, how will new concepts such as crypto art, blockchain and NFTs change finances in the art world?

AT: The value of art has always been subjective, based on its own unique currency determined by those who acknowledge and collect it, but not always made public. Blockchain and NFT technology facilitate an evolution of this valuation process by transparently enhancing the public tracking of changes in ownership and value. Works of the past involve an extensive review process to determine proprietorship and authenticity which can now be more easily verified with technology.

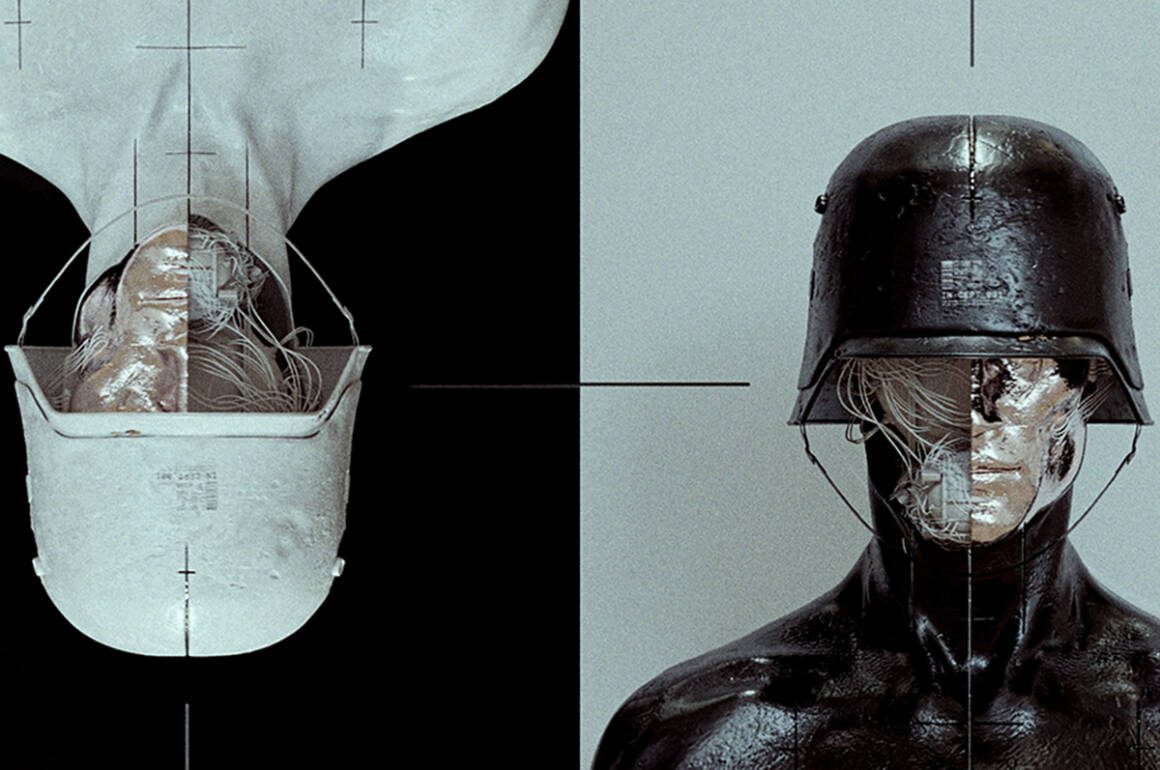

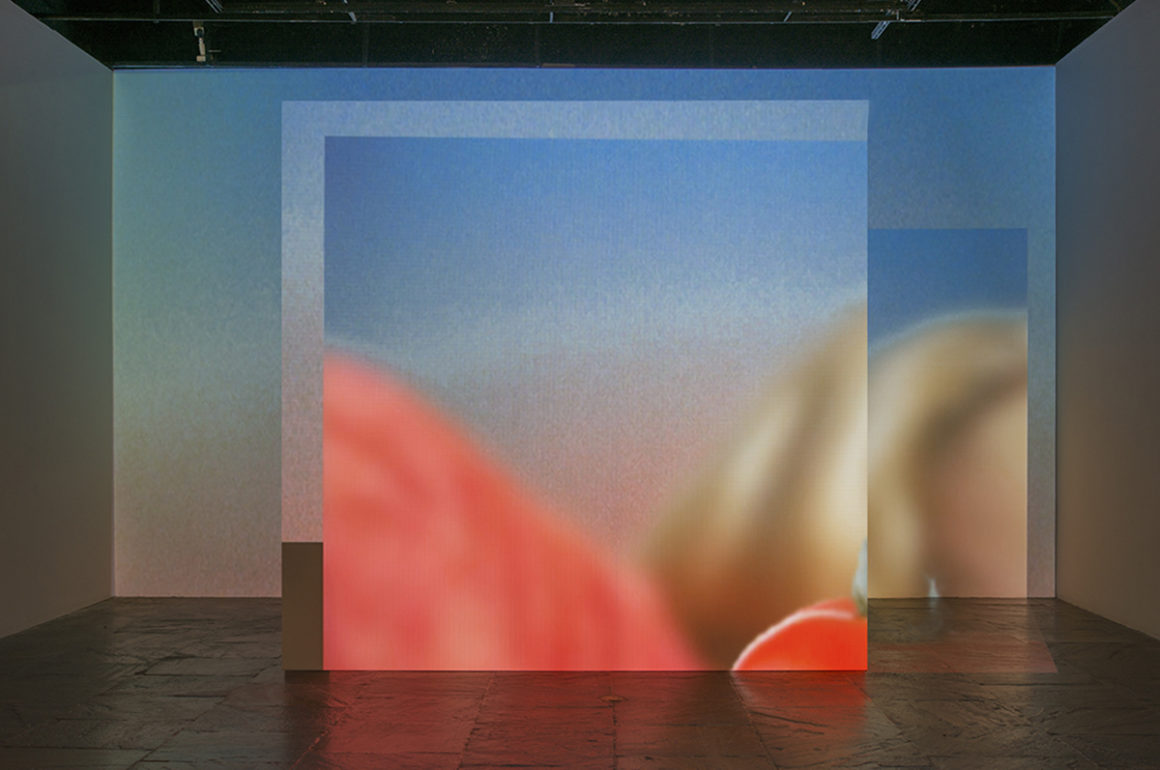

LUX: You recently featured at Frieze London collaborating with W1 Curates, Seth Troxler and Richard Mille. How did you find the collaboration and do you enjoy digital art’s interdisciplinary possibilities?

AT: Showcasing an art exhibition during Frieze London was a monumental and wonderful experience. I greatly enjoyed working with everyone at W1 Curates and being introduced to Seth Troxler and the team at Richard Mille. Bridging the relationship across multiple industries through art created such a profound moment which everyone celebrated and commemorated together. This blending of media should hopefully inspire others to continue to follow suit with future collaborations and more venues, as it truly creates a surreal magical experience.

LUX: You have a particular interest in cars. What inspires you about them?

AT: My fascination with cars is a childhood passion that has endured time. The love of cars encapsulates so many aspects I cherish in life: the intricate design, precise engineering, scientific underpinnings, technological marvels, and the connection between humans and machines. I don’t merely see cars as vehicles of transportation. I enjoy the mental retreat to a space of childlike innocence, and perceive the deep-rooted romance within them.

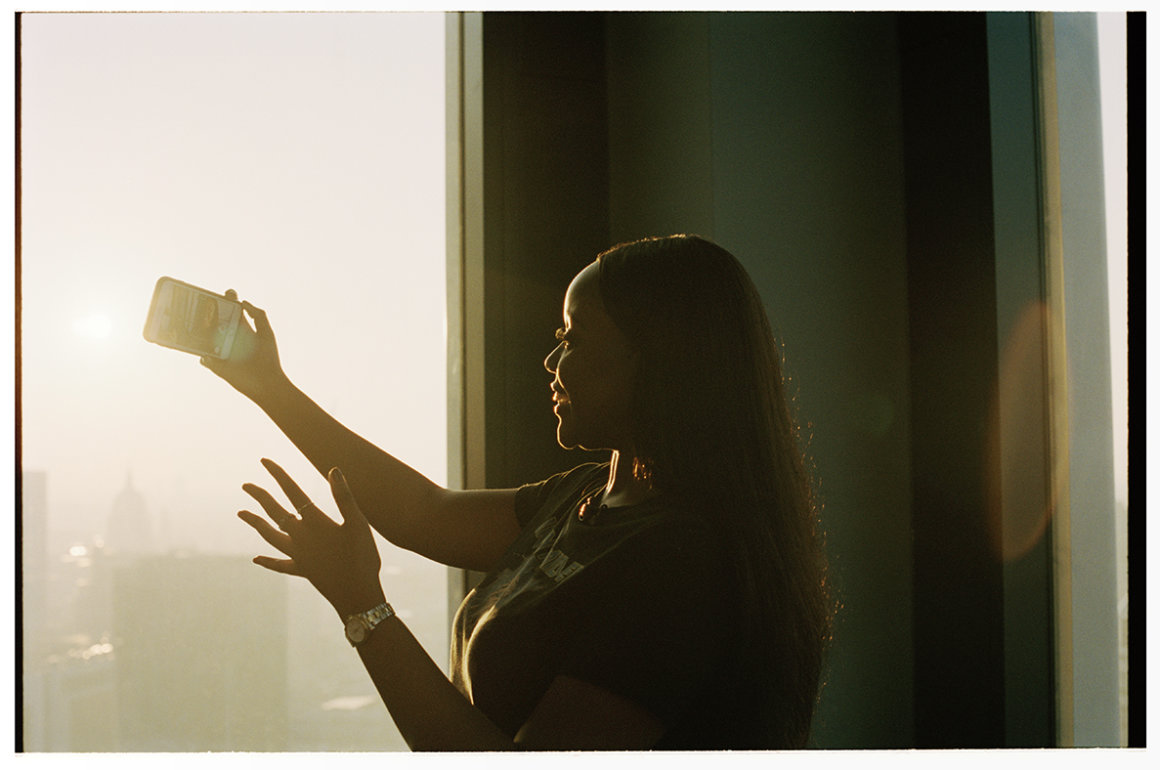

Following by Ash Thorp from the ‘Nascent’ series

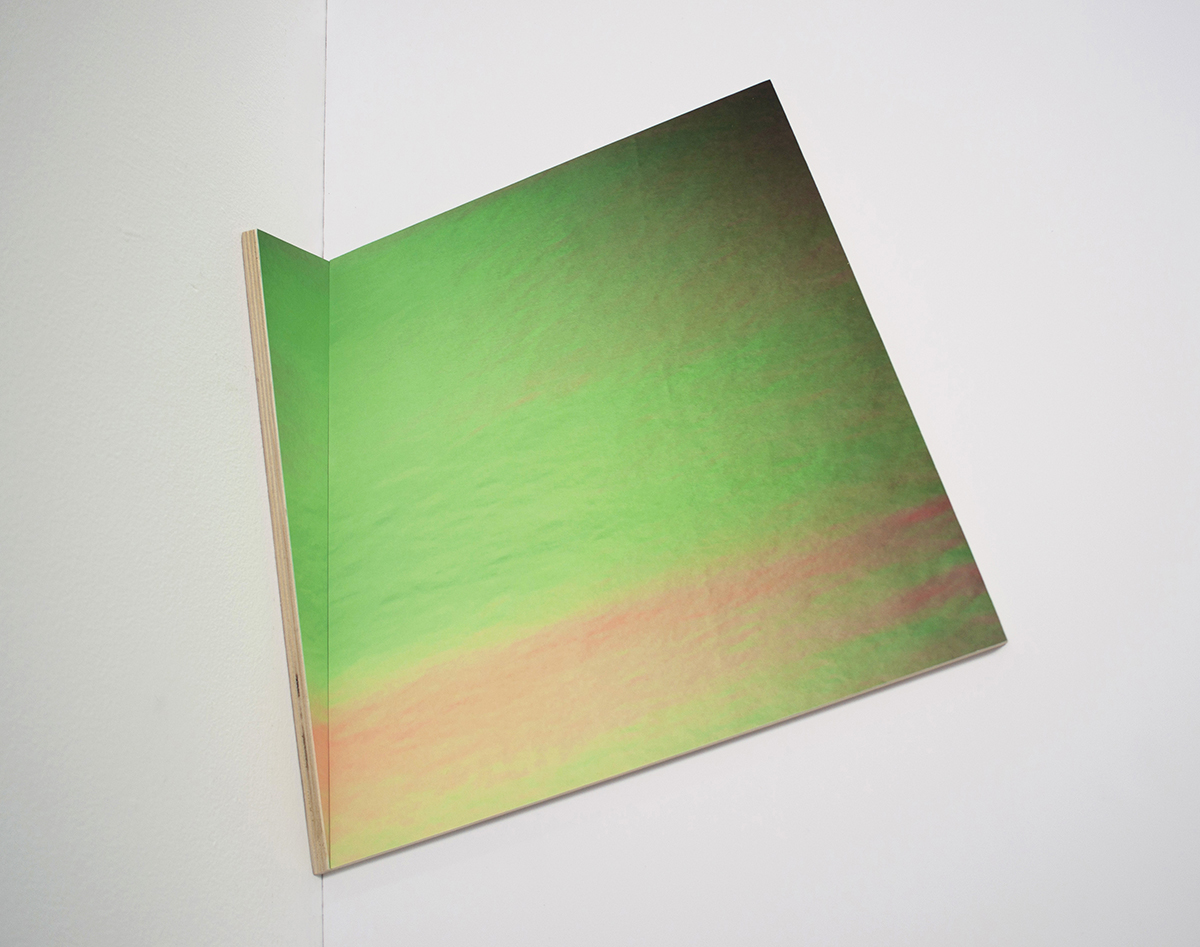

LUX: How has your digital art changed over time?

AT: Previously my work was primarily recognized on feature films like the Batman, but now I’m also able to showcase the more personal evolution of my digital art with blockchain technology. I’ve found the opportunity to delve deeply into a personal journey of my thoughts and curiosities. It’s a transformative journey that has significantly shaped both my perspective and my artistic endeavors, granting me the sovereignty to explore.

LUX: What are your upcoming projects and where do you see your art heading?

AT: I’m currently engaged in several exciting projects that cannot be disclosed just yet until their public release. As for the direction of my art, my overarching objective is to continue self-discovery, to understand further why I create this work, and to recurrently explore the fundamental answers to life.

We’re talking over Zoom and email. Though technology facilitates our distanced conversation – San Diego to London – in my opinion, it is less personal than an in person meeting. Are there areas of digital art which, relying on technology rather than the body or physical tools, make the relationship to the artist less personal? If so, does it matter?

Art curation is necessary and often overlooked in the digital space, primarily due to the convenience of technology. Traditional works often demand a dedicated physical visit to a specific gallery or institution, which assists a narrative that it must be of higher value and experience. The challenge for digital art lies in finding opportunities for it be equitably appreciated and valued, for it to be seen to enhance our lives as much as any other form of art.

Find out more: www.altcinc.com

One place where the impact of the digital revolution is most evident is on online platforms such as

One place where the impact of the digital revolution is most evident is on online platforms such as

Recent Comments