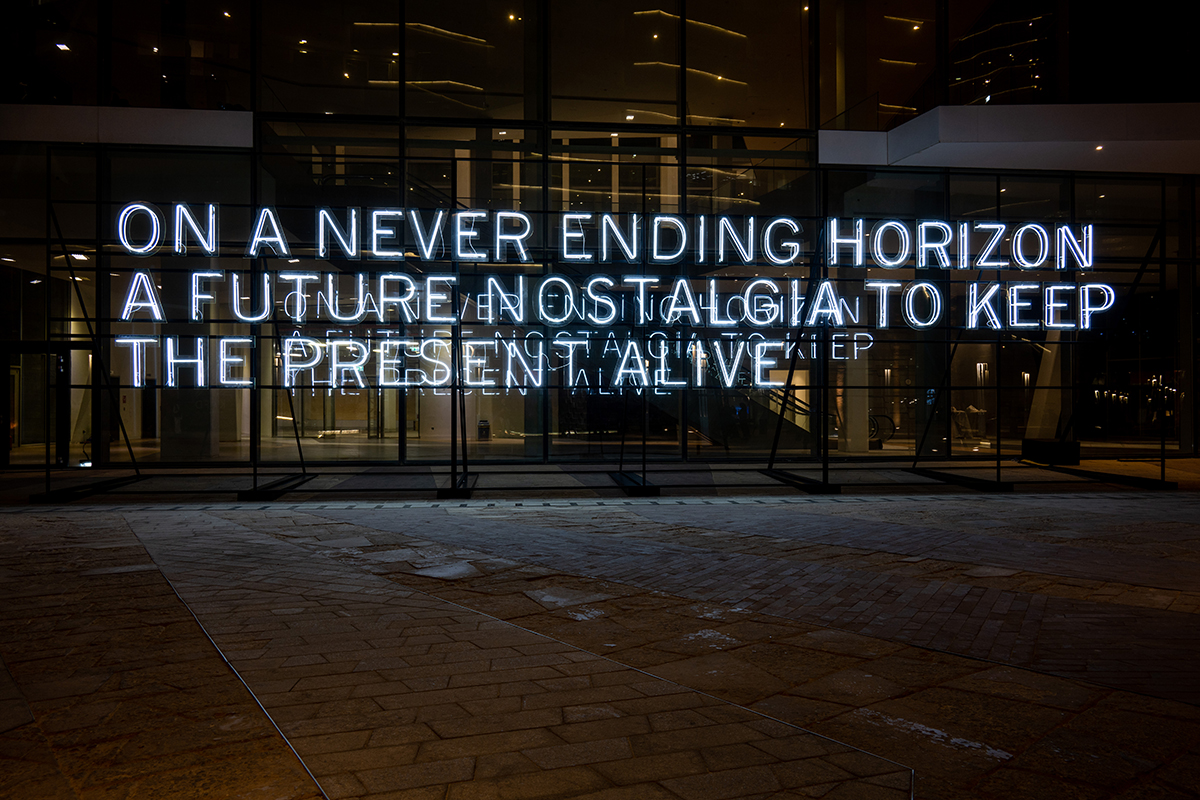

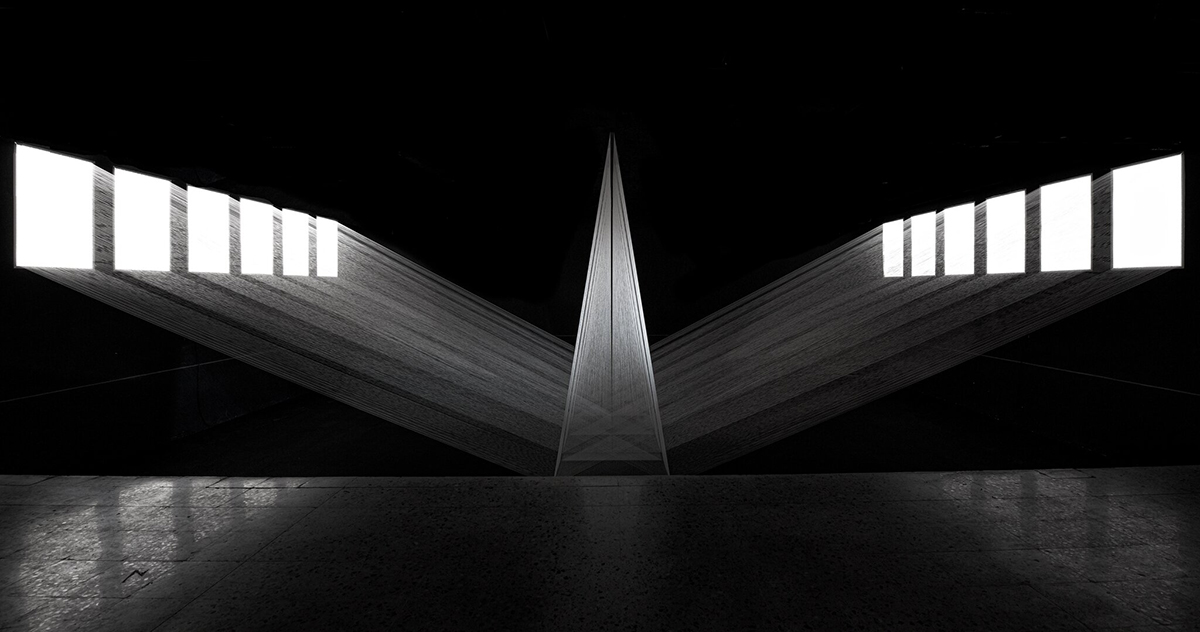

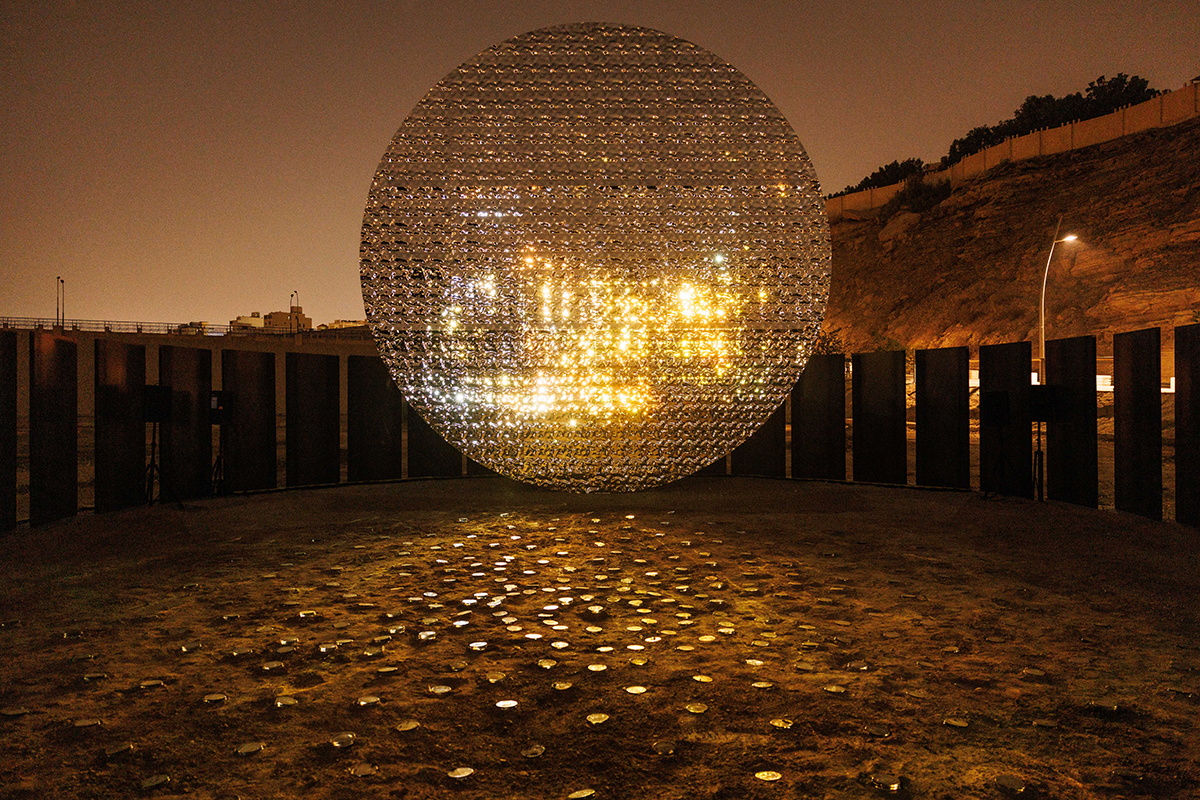

Light Horizon by artist Sabine Marcelis in Wadi Namar, part of the Noor Riyadh Festival 2022

Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia, has not been a city you would associate with art. Yet it has just staged the one of the most spectacular outdoor art shows the world has ever seen. LUX travelled there and was impressed with the breadth and depth of art and local participation

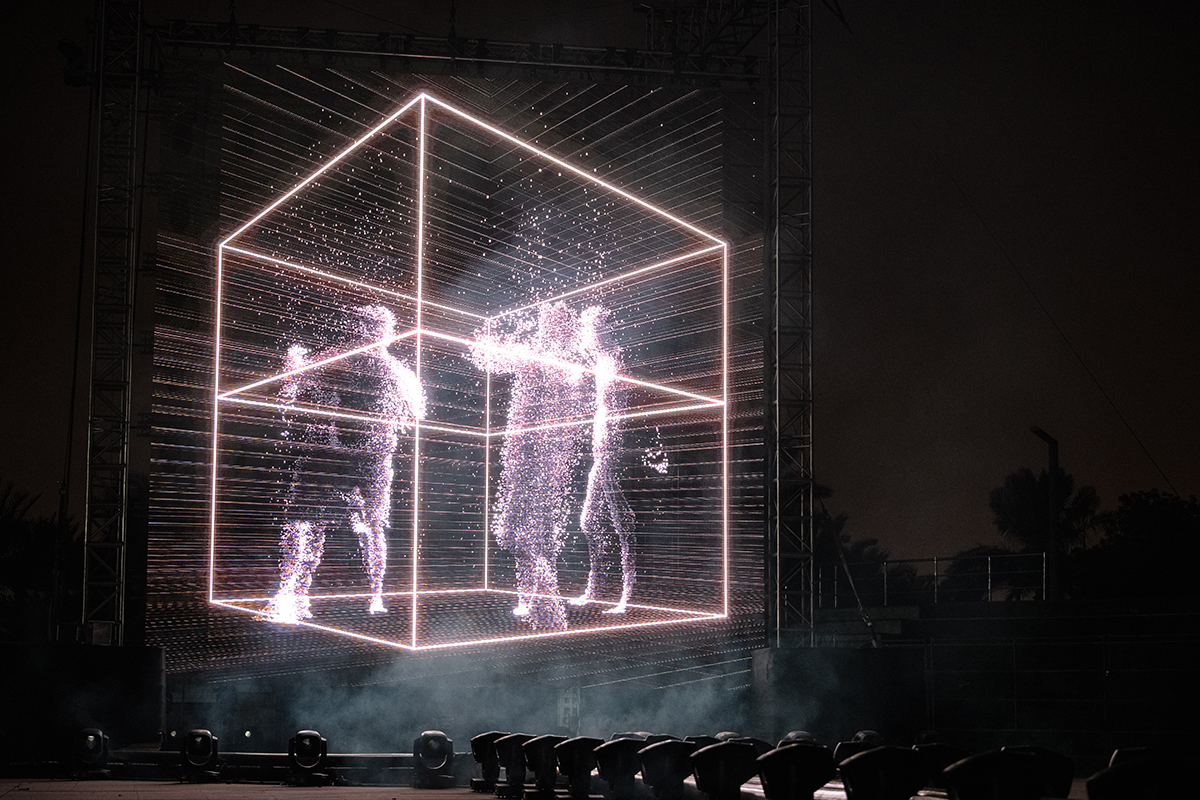

It is a warm autumn evening on the outskirts of a vast city in the middle of a desert. Darkness has fallen, and on the walls of a courtyard, thousands of illuminated Arabic letters are rising and falling, projections streaming up and down and disappearing temporarily into space before reappearing. Families and other visitors, drifting in and out of the courtyard, are enraptured.

A couple of minutes’ walk away, another larger than life light artwork is playing out. This is on the back wall of another building, viewable from a specially made area at the back of its garden, a story of a dream, animated in bold colours and dramatic scenes in a massive projection four stories high. We won’t give away the plot of ‘Fantastic Dreams’ by Morgane Phillippe, playing on a loop in this dramatic setting, but it’s pretty striking.

A couple of minutes walk away, in a piazza, is another artwork, this one seemingly of swathes of red tentacles beneath a huge crimson light, weaving in and out of the exoskeleton of a building. Small children zoom around below it on their scooters, delighting in dodging the crowds clustered below chatting to the artist, Grimanesa Amorós.

Carving the Future by Saudi artist Obaid Al Sufi. The festival showcases local and international artists with dramatic, complex and beautiful installations

This is just a taster, a fraction of the art on show, in what is without doubt the most spectacular outdoor art exhibition at the moment in any city of the world. It sounds like it could be Venice during the (now finished) Biennale, but the scale of the public art here is much bigger, and it is not confined mainly inside buildings and pavilions as it is in Venice.

This is in fact the second edition of Noor Riyadh, a festival of art and light created by the authorities in the Saudi capital to turn the rapidly-developing city into a global art destination and a town where artists can be seen to be thriving.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

For those of us from outside the country who had a view of Saudi Arabia as a place where culture was not encouraged, Noor Riyadh was quite a surprise – doubtless also for many of those in the country itself, as change is coming fast. Noor Riyadh would not have even been conceivable just three years ago, someone closely associated with the festival told me. It is part of a broader plan by the country’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, to catapult the country from being a kind of wealthy recluse of the Middle East, as it has been to date, to a cultural and artistic force.

The involvement and support of local artists is fundamental, another source told me. Although they did not say it directly, I suspected they were thinking of contrasting themselves with neighbours like Qatar and Abu Dhabi, which have, in the last few years, gone from zero to hero in terms of the global art scene, with Qatar acquiring one of the biggest collections of modern and contemporary western art in the world, and Abu Dhabi opening a Louvre and a Guggenheim as if they were architect-designed fast food franchises: but neither of them having much concern about their own culture or artists, perhaps because of their diminutive size. (Qatar does have a stunning Museum of Islamic Art, but the works are from all over the Arab and Byzantine lands, as well as Iran).

De Anima, 2022 by Sarah Brahim. This was the second edition of the festival of light and art based in the Saudi capital

In Riyadh, by contrast, it is all about blending top local artists – and encouraging many more – with expertly curated artworks from the rest of the world, and, importantly, not shutting them away in a private collection but having them on display for all members of the public to see, with no charge, at several locations in this vast city.

One of the co-curators of Noor Riyadh is Hervé Mikaeloff, an internationally renowned art figure who works closely with Bernard Arnault of LVMH, and brands like Dior. I had last chatted with Hervé when he gave me a private tour of the Miss Dior art exhibition he curated at the Grand Palais in Paris. Here he is now, having helped bring in some of the dazzling international art names, at dinner with a crowd of fellow curators, museum directors and collectors at Il Baretto in the King Abdullah Financial District.

Hervé told me, over a glass of mineral water (alcohol is still banned in Saudi Arabia): “We wanted to bring international artists for people to see what they couldn’t see elsewhere. , to show them quality artworks from international players. There are plenty of local artists also. Through the artwork we presented. ,we wanted to bring new art but also an international sensibility to show what is happening around the world. That is why the [2022 festival theme] is called We Dream of New Horizons. I think we succeeded, the public is there, Noor Riyadh is not only for VIPs, it is very popular and I really liked that.”

There was a palpable character of Noor Riyadh being a Saudi initiative, something created by locals, for locals, with the help of very well selected international experts, which Hervé backed up. “Riyadh is not like Dubai where there are people from everywhere around the world. There is local culture and history and I find that very interesting.”

Cupid’s Koi Garden by Eness, in Salam Park. Installations from local and international artists were showcased over a wide geographical area

Riyadh is a huge city, much bigger than I expected it to be in terms of surface area. With the exception of new developments like the rather striking King Abdullah Financial District, where some of the most spectacular installations were placed, much of the city is quite austere: think suburban Orange County with fewer swimming pools. But changes are, without a doubt, happening here. In expensive shopping malls, cafes and fast food restaurants alike, I saw local women sitting without head coverings – since 2019, it has no longer been compulsory for women to cover their hair and wear and abaya in Saudi Arabia, although the majority of women still do. Even the latest advertising billboards for swanky property developments are cleverly photographed so it can’t quite be told whether the woman in the aspirational young couple looking up at the apartment development is wearing a headscarf or not. Judged by Western standards (and whether Western standards are correct for the world is a whole other debate; I’m not always so sure), there is a long way to go in terms of equality, but nobody can deny things are moving in the right direction, quite fast.

And there can be little doubt about the aspiration for quality in the art. Although this was just a second edition of the festival, The Royal Commission for Riyadh City, ultimately in charge of the art program as a whole, sought and received good advice and went for the best. At dinner one night I found myself quite at random sitting next to Alicja Kwade, one of the most prominent and respected artists in Europe, represented by the highly respected König Gallery in Berlin. The others at the table included a well known gallerist and museum director from Europe. I went to view Alicja’s complex, architectural work, Morgana, the next day.

Earth by Spy at King Fahad National Library. The festival exhibits over 120 installations across 40 locations around Riyadh

Meanwhile Charles Sandison, the artist who created my personal favourite work there, The Garden of Light, the rising and falling projection of Arabic letters in the nighttime courtyard, told LUX:

‘With my artwork I wanted to create a technological complex visually dramatic architectural intervention – but also provide an intimate environment where the viewer could find their own place to be. The context of the festival opened up new possibilities and cultural dialogues for my work which I hope will continue’.

The Garden Of Light by Charles Sandison. The festival is co-curated by Hervé Mikaeloff, Dorothy Di Stefano and Jumana Ghouth

The group visiting the opening of the show comprised a significant slice of great and the good of the art world, so much so that if you had funnelled them onto an island in the first week of the Venice Biennale as the guestlist for Francois Pinault’s celebrated party, the French luxury tycoon would not have been disappointed at all.

Another international artistic name, Neville Wakefield, curated the “From Spark to Spirit” exhibition at Noor Riyadh, and told us: “As explored in ‘From Spark to Spirit’, it is evident that light in this world can be seen as an integral means of communication. We are now connected to each other by screens – by the light of information. We communicate with one another through the direct manipulation of light to form words and images that together map a collective consciousness, bringing us together in an era of rapid technological and cultural transformation.”

I See You Brightest in the Dark, 2022 by Muhannad Shono. The range of light art on show includes immersive site-specific installations, public artworks, sculptures, art trails and virtual reality

The festival was put together in several distinct areas of town, and casual visitors from overseas (I didn’t spot any this time, but they will doubtless come in years to come as the event gains credibility and respect in the art world) need careful instruction on where to go and how to get there.

The soul of the festival is perhaps the multistorey light installation by local artist Muhannad Shono, who told us: “The work is an attempt to weave back into tangibility the intangible. The four rooms are a journey through loss, memory and acceptance. The installation exists at the thin line that separates the perceptible and the invisible, the here and those we can no longer hold close.”

Read more: Never-Before Seen Andy Warhol Photographs at the Beverly Hills Hotel

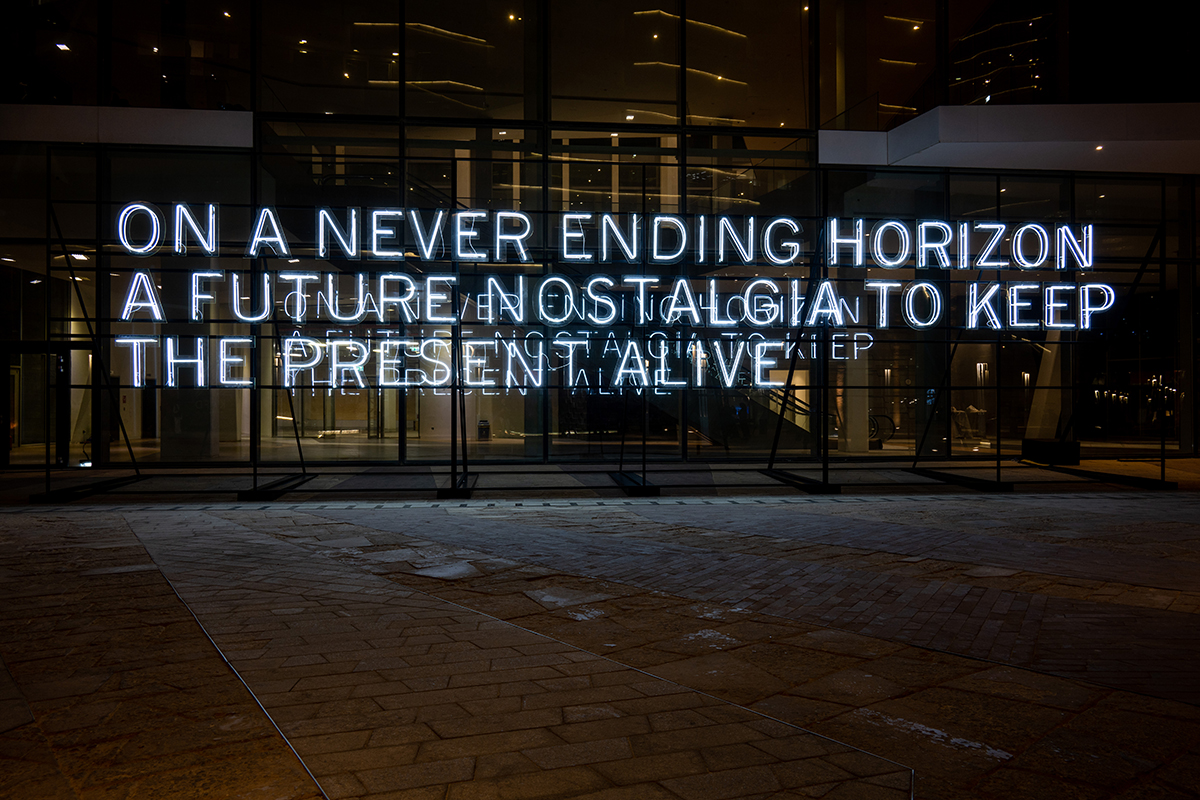

In contrast to the works in the JAX area, in converted warehouses on the edge of the city, was the spellbinding spectacle installed in the swanky new King Abdullah Financial District, a kind of Wall Street without the beer, recently built, architecturally striking and with aspirations to be the leading financial centre in the Middle East. Here, you can’t miss the light poem installed in giant letters: “On a Never Ending Horizon A Future Nostalgia to keep the Present Alive”.

The artist, Joël Andrianomearisoa, was there (many artists were there with their works, which was both surprising and inspirational), and told us it was: “A light poem for Riyadh. Some words suspended on the horizon of our emotions to tell the story of the present, to create the desire of the past and to affirm the vision of the future. On a never ending horizon a future nostalgia to keep the present alive.”

Artwork by Joël Andrianomearisoa. A core element of Noor Riyadh is its comprehensive public program of over 500 events such as tours, talks, workshops, family activities and music

And the works mentioned at the top of this article were in another area completely, the diplomatic quarter, on yet another side of town. There were more works in the desert. These distances are not small: depending on where you hail from, think Venice Beach to Hollywood Hills to downtown LA, or Chelsea to Hackney to Lewisham, or Prenzlauer Berg to Grunewald and back, to begin to get an idea.

This makes the whole thing even more remarkable in a way. Many ambitious festivals would have set themselves in a single location. To show over 120 artworks from 40 countries in 5 districts across the city is not just ambitious but visionary. And if it was part of the vision that middle class families should bring their children to be scooting around the artworks, or laughing as they ran through a light tunnel installation, then bravo.

Rawdah, 2022 by Abdullah Alothman. The festival exhibits more than 120 installations by over 100 artists

Informal public participation and enthusiasm not just for the works, but for the context and joy that artists can bring, is fundamental to creating a momentum around art from the ground up: the Pompidou Centre demonstrated this in the 1980s by turning the Beaubourg area of Paris inside out, and TATE Modern continued spreading the fun in London in the 2000s. Fun is not, I suspect, a word that appears alongside Riyadh in many Google searches to date, but Noor Riyadh used the playfulness of these striking public installations to appeal to the local population and win hearts, first and foremost. For the international visitor, it was the quality and sheet quantity of works that spoke for themselves.

Noor Riyadh was the single best art spectacle in the world at the time of viewing this year. That’s quite an achievement, and if in future years more local artists join in with enthusiasm, and more art world influencers and collectors are visiting, Riyadh may just turn into a prime destination on the global cultural map – and most importantly, a centre of artistic creativity in its own right.

Noor Riyadh is available to visit until Saturday 4th February 2023

Find out more: riyadhart.sa/noor-riyadh

In the second part of our Driving Force series from the AW 2022/23 issue, LUX’s car reviewer gets behind the wheel of the Audi R8 V10 Spyder.

In the second part of our Driving Force series from the AW 2022/23 issue, LUX’s car reviewer gets behind the wheel of the Audi R8 V10 Spyder.