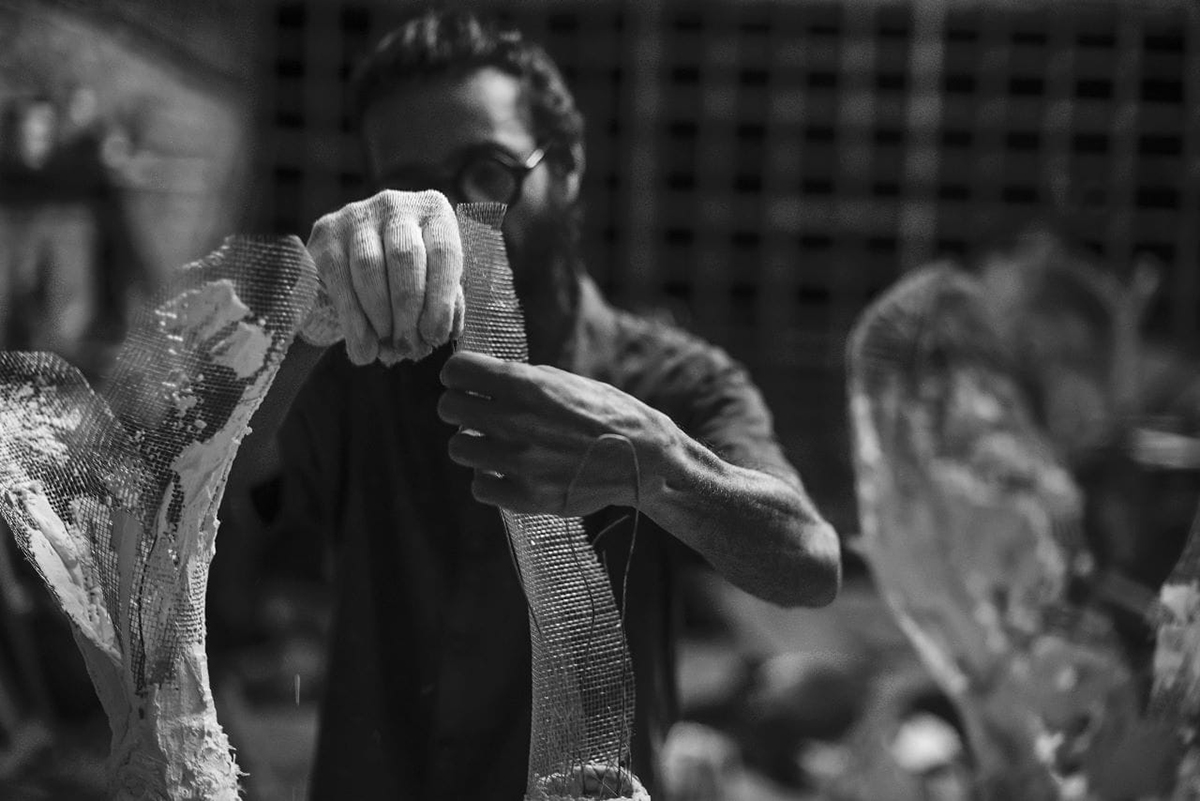

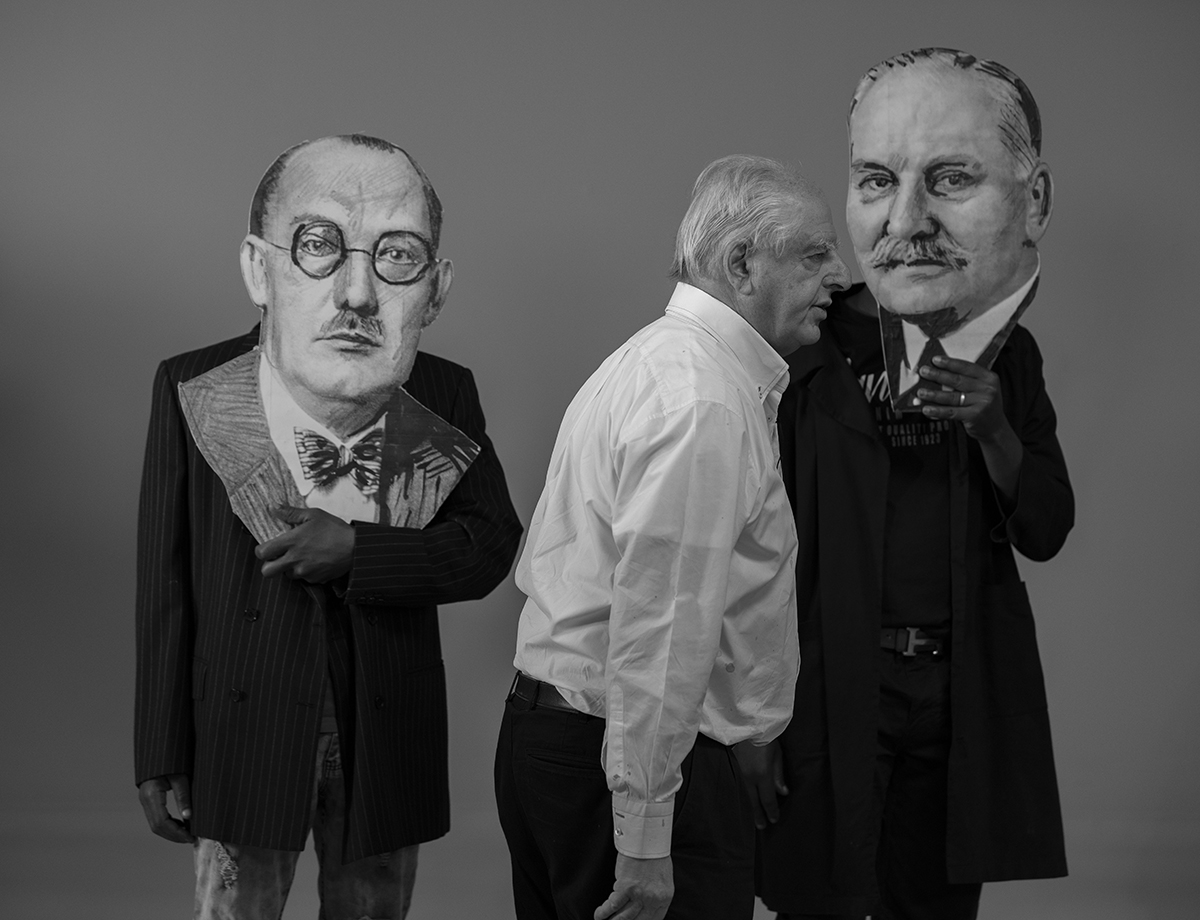

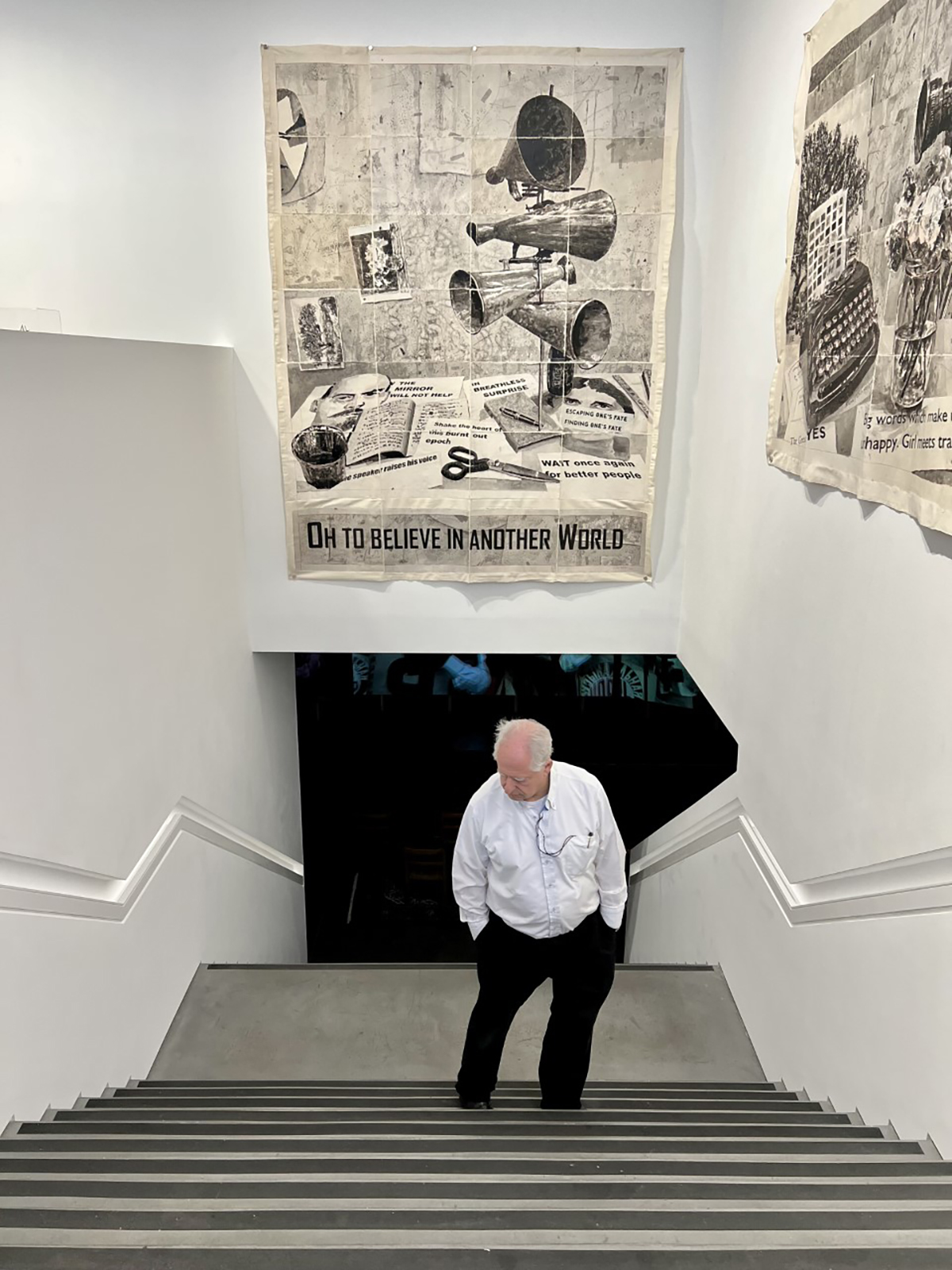

Camp Xakanaxa, on the Khwai River bank

Ella Johnson travels through Botswana on an eco-safari, where the highlight is encountering more hippos than humans – in a landscape owned by wild creatures and where humans are just fleeting visitors

Arriving at Botswana’s Makgadikgadi salt pans in the dry season feels like landing on the moon. Travel westwards by helicopter from Leroo La Tau and watch the dense African bush melt into spacescape. Step out of the aircraft onto a vast flat plain: besides the grey earth cracking underfoot, a total absence of sound predominates.

It is an extraordinary place to be on the final leg of an ultimate safari tour through northern Botswana’s Okavango Delta and beyond. A designated UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Okavango is a vital wetland region teeming with biodiverse wildlife and habitats, and is the chief stomping ground of Desert & Delta Safaris, one of Botswana’s foremost tour operators. We have been touring with Desert & Delta for the past seven days, encountering creatures and terrains of encyclopaedic variety – and now this most surprising, lunar-like landscape.

Elephant viewing from one of the EVs at Chobe Game Lodge

We had started out at Chobe Game Lodge, in the Southern African country’s northeast. It is the only permanent game lodge inside Chobe National Park (so named after the Chobe River that intersects it), and we encountered 33 elephants at the waterfront before checking in. We also get an hour’s head start over neighbouring lodges on the morning game drive: for us, the difference between a rendezvous with three lion cubs and their vanishing as other trucks piled in.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

The government’s “high-value, low volume” tourism strategy finds full expression at Chobe. The lodge, managed by locals, was the first in Africa to hire an all-female guiding team (the Chobe Angels) and the first in Botswana to electrify its safari fleet – the solar-powered boats and EVs were a game-changer when it came to proximity with the Big Five.

Chobe is as upmarket as it is eco-conscious. It is run on biogas and has its own recycling plant, where waste plastic and glass are repurposed as decking. It is also where Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton celebrated honeymoon number two in 1975, and their very private suite has an infinity plunge pool. Our own room featured a roll-top bath and objets d’art from Zimbabwe, Morocco and Egypt; colours were vibrant and textures natural. Our favourite hangout was the cave-like bar, to which we headed at aperitivo hour for Amarula (Botswana’s answer to Baileys) before a meal on our private terrace.

the Honeymoon Suite patio at Chobe Game Lodge

Next came perfect isolation at our next stop, Nxamaseri Island Lodge, at the uppermost point, or Panhandle, of the Okavango. We reached it from Chobe via a short plane journey west and a boat ride through the Delta’s permanent, papyrus-lined floodwaters. The lodge occupies its own side channel, meaning we encountered more hippos than humans there. Our lodging – one of nine, connected via boardwalks through the overgrowth – was comfortable, albeit with fewer bells and whistles than Chobe. Evening meals were communal and hearty. Wi-Fi was intermittent.

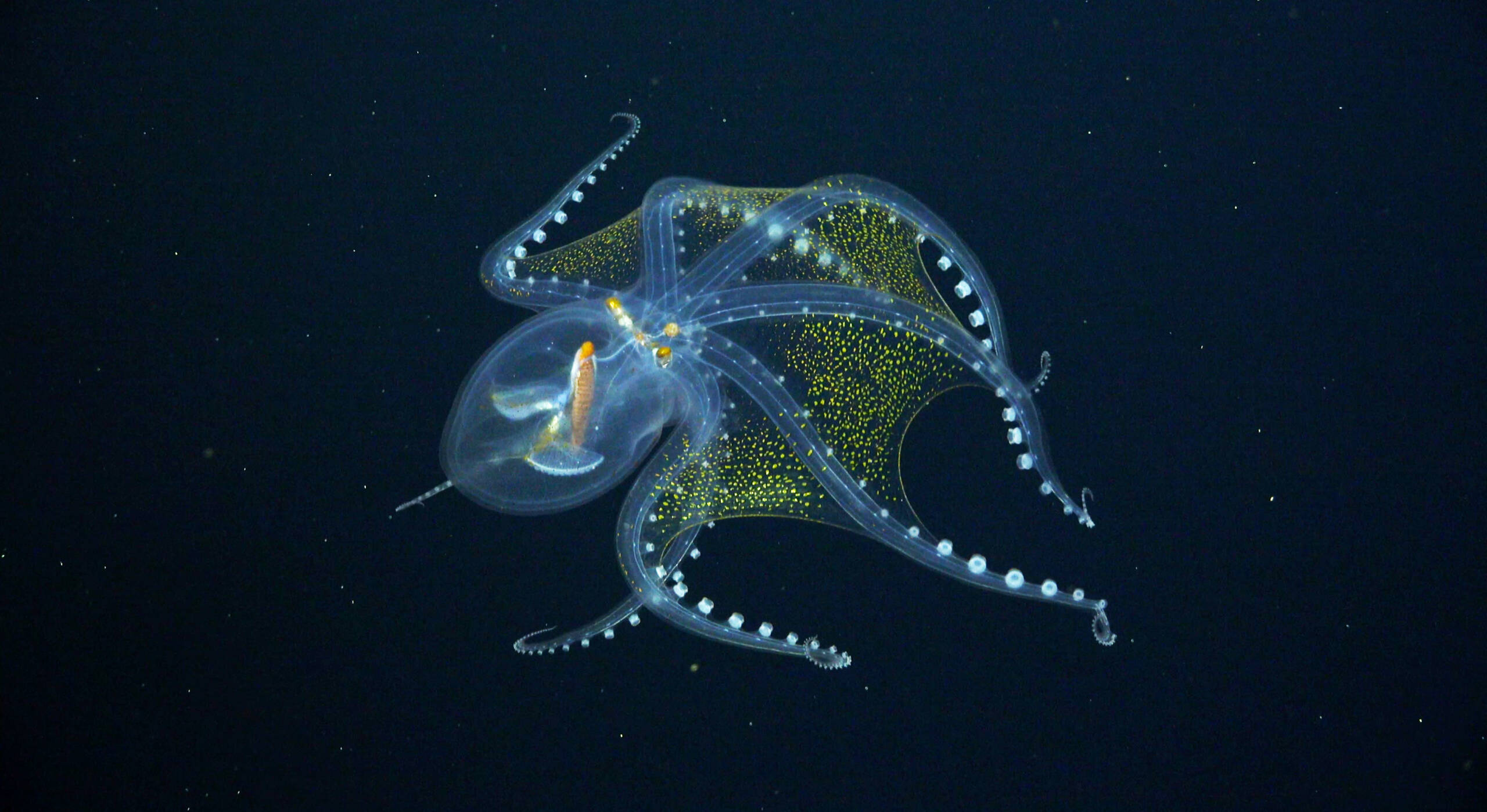

The Nxamaseri region is home to around 325 of Botswana’s 500 native bird species, and we soon became adept at naming slate-coloured boubou, malachite kingfisher and Pel’s fishing owl from the comfort of our evening river cruise, G&Ts in hand. We had a more sobering experience in the mokoro, traditional wooden canoes that brought us nose to nose with crocodiles (perfectly safe, our guide testified).

We therefore welcomed the land-based trip to the Tsodilo Hills, another UNESCO World Heritage Site nearby, with cave paintings by bushmen including the San and Bantu, from 800 to 1300AD, and some reputedly far older. Although their meanings have become less intuitive over time, these paintings have been well shielded from the elements by way ofrocky overhang and ancient baobab. It is also, perhaps, the Botswana we had come to find. From our guide, Metal, we had already learnt that elephants have ten different vocalisations; that the Vogelkop bowerbird likes to decorate its nest with shiny things; that it is possible to deduce, from a pair of erratic footprints, that a guineafowl has recently met its end with a cheetah. So, too, as we studied the Tsodilo paintings more closely, rich patterns emerged.

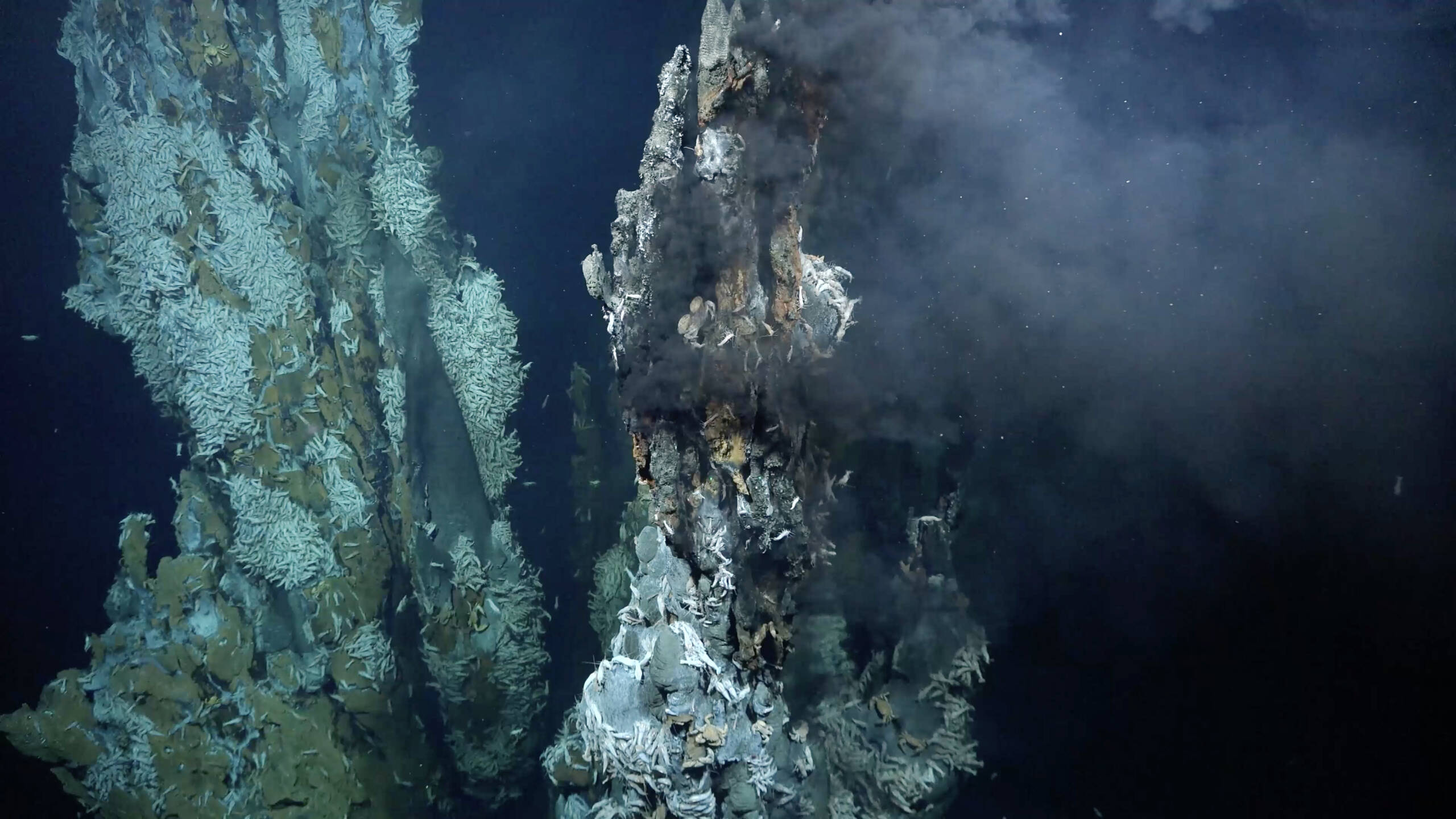

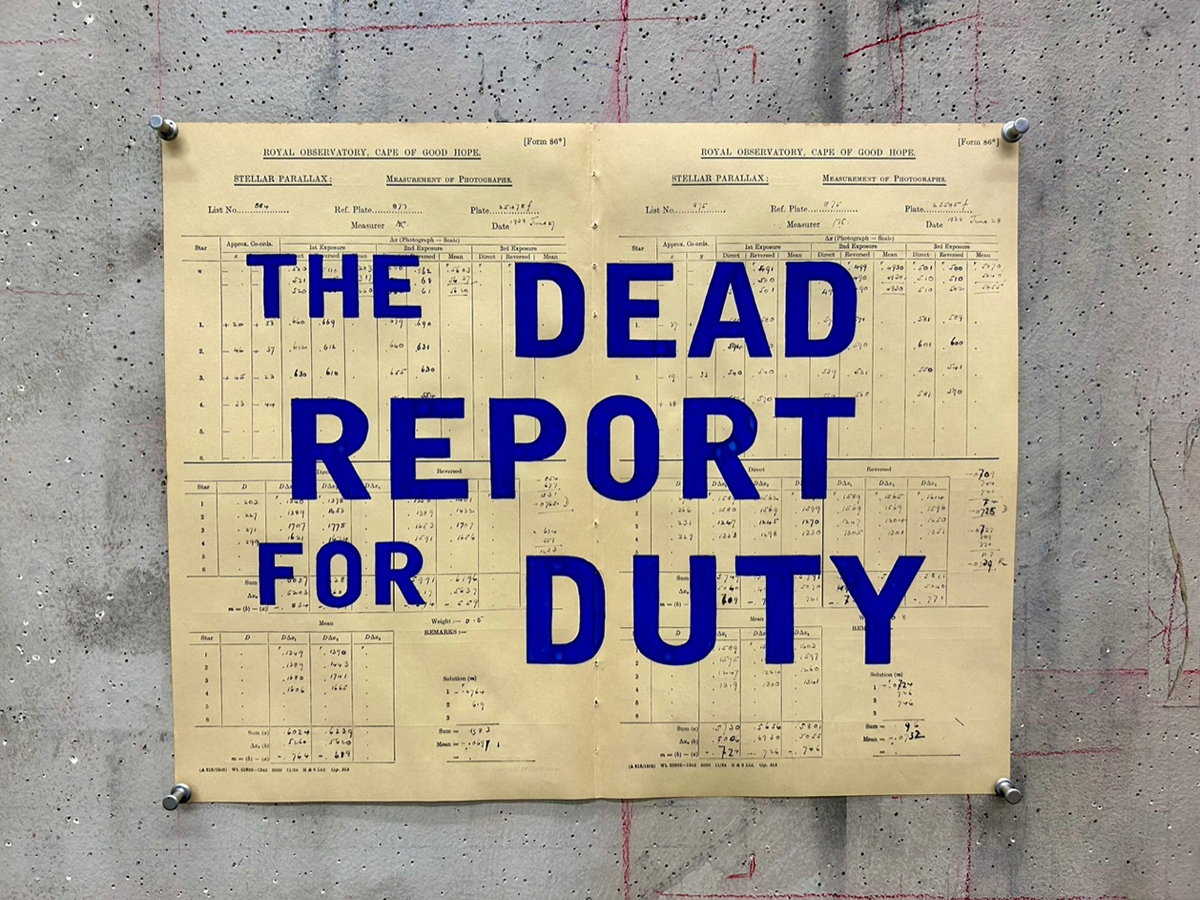

Outdoor dining at the glass-fronted Leroo La Tau

Another short flight east across the floodwaters brought us to Camp Xakanaxa, on the banks of the Khwai River, in the arid Moremi Game Reserve. Here is a sense of drama: petrified trees dot the horizon; the fragrance of wild sage hangs heavy. Fitting, then, that our guide, TS, would race us out to catch sight of two evasive cheetahs after hours (they slinked across our path unexpectedly, our wheels kicking up dust as we screeched to a halt). Or that we’d have a close shave with Oscar, a battle-scarred hippo who loiters in Xakanaxa’s communal areas, after. Thank goodness, then, for Xakanaxa’s selection of South African reds (Saxenburg, Leopard’s Leap) to decompress after the action.

The kaleidoscope shifted again at Leroo La Tau, our final stop, in the Makgadikgadi Pans National Park. This is an ever-changing, aqueous environment – viewable from one of 12 glassfronted thatched suites hovering ten metres above the Boteti River, where we spent an entire afternoon watching zebras rove in their hundreds.

Read more: Ocean Fantasy: the Ritz Carlton Maldives, Fari Islands

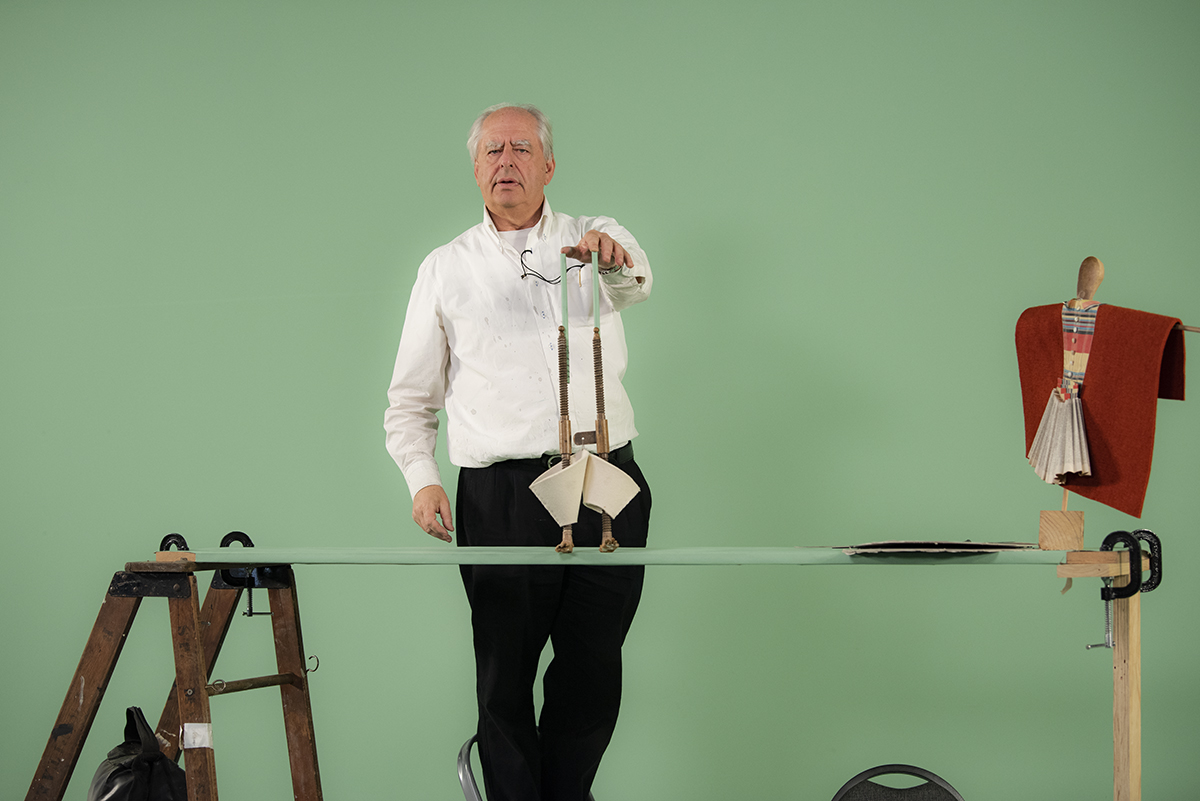

Desert & Delta offers a salt-pan sleep-out for guests staying at Leroo for three nights or longer, but take our advice and pay upfront for a helicopter ride to beat the five-hour drive through the desert. On touching down, our personal chefs cooked a three-course meal for us on the flats; our bed was as if transposed from a Four Seasons, king-sized with crisp, white sheets – and unmediated views of the Milky Way. At roughly the size of Belgium, the Makgadikgadi salt pans are the biggest in the world: to sleep on them, tentless, was to experience darkness and solitude for the first time.

Flying back to Leroo, the moonscape slid back to more familiar bush territory. It is paradoxical, perhaps, that the highlight of our safari was a place devoid of life altogether. Yet it speaks directly to the appeal of a country whose ancient landscape continues to yield up the new and unexpected. In tapping into its extremities, Desert & Delta Safaris takes an old classic and offers a highly original take.

An otherworldly sleepout at Makgadikgadi salt pans

Getting there

We travelled to Botswana via Doha with Qatar Airways. The airline’s signature Qsuites in business class have sliding-door partitions to lose visibility of fellow passengers and bring an extra element of privacy (the partitions reach to chest height, so it’s not quite like having a full suite). On boarding we were greeted with a glass of Charles Heidsieck Rose Millesime and Diptyque amenities and an on-demand dining service with a broad choice (we went for cheese and port followed by a warming Karak Chai). More sociable passengers stopped by the Sky Bar, in its own section of the plane, for a negroni mid-flight. On our layover at Doha, we stopped in the Al Mourjan Business Lounge for sushi and more champagne. Its galactic art installation and water feature made it easy to pretend we were in a five-star hotel.

Find out more: qatarairways.com

Our hosts

Chobe Game Lodge, Nxamaseri Island Lodge, Camp Xakanaxa and Leroo La Tau are among nine Botswana safari locations owned by Desert & Delta Safaris and located within Botswana’s wildlife destinations.

Find out more: desertdelta.com

This article was first published in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of LUX

Recent Comments