Philippe Sereys de Rothschild photographed at the Grand Mouton residence

Philippe Sereys de Rothschild, head of the Mouton Rothschild family wine empire, recently inaugurated a new prize for the arts. Darius Sanai celebrates with him and his family members on the night of the awards, and speaks to him about patronage, the wine world and running one of the world’s most celebrated family businesses

Photographs by David Eustace

It’s a cool, clear evening in the vineyards of the Médoc, the triangular strip of land that stretches from Bordeaux to the Atlantic Ocean, along the estuary of the Gironde river, and which contains the world’s most celebrated wine estates. From the terrace of Château Clerc Milon, rows of perfectly groomed vines stretch out to the left and right; immediately below the terrace, a lawn drops down along a path lined by exotic bushes, to a steel-and-glass marquee. Beyond this temporary structure, which was erected the previous day and will be gone by morning, are more vineyards, undulating up towards Château Mouton Rothschild, over the brow of a small hill.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

The Mouton Rothschild vignoble in Pauillac

As the sun goes down, guests sip Rothschild non-vintage Champagne or glasses of deep red Château Clerc Milon 2009, chatting about the show they have just seen. Suddenly, there is a musical introduction and all heads turn towards the stairs leading up from the lawn, from which 20 or so beautiful young people emerge, with a mixture of shyness and performance, and walk two by two through the crowds before dispersing into smaller groups and chatting to guests over glasses of Champagne.

The new arrivals were dancers from the Ballet de l’Opéra National de Bordeaux; earlier, they had given the performance everyone had come for, in the marquee by the vineyard, in front of 100 seated guests. The show marked the second edition of the biannual Prix Clerc Milon de la Danse (Clerc Milon dance prize), awarded by the Philippine de Rothschild Foundation to two outstanding dancers from the Bordeaux ballet. The two winning dancers, Alice Leloup and Marc-Emmanuel Zanoli, had been awarded their prizes at the end of the show; now, after a brief interval, they and their colleagues were emerging, perfectly attired for the evening, to join the soirée. It was a magical moment during a spectacular evening.

The private wine cellar at

Château Mouton Rothschild

The prize is the brainchild of Philippe Sereys de Rothschild, Chairman and CEO of Baron Philippe de Rothschild SA, and his siblings, Julien de Beaumarchais de Rothschild and Camille Sereys de Rothschild. When their mother, the legendary Philippine de Rothschild, passed away in 2014, they inherited one of the most famous empires in wine. Their company, Baron Philippe de Rothschild, owns Château Mouton Rothschild, one of the five ‘first growths’ of Bordeaux and among the most celebrated and expensive red wines in the world; Château Clerc Milon and Château d’Armailhac, also classed-growth Bordeaux châteaux; the Bordeaux brand Mouton Cadet, and much else.

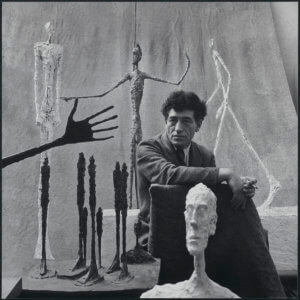

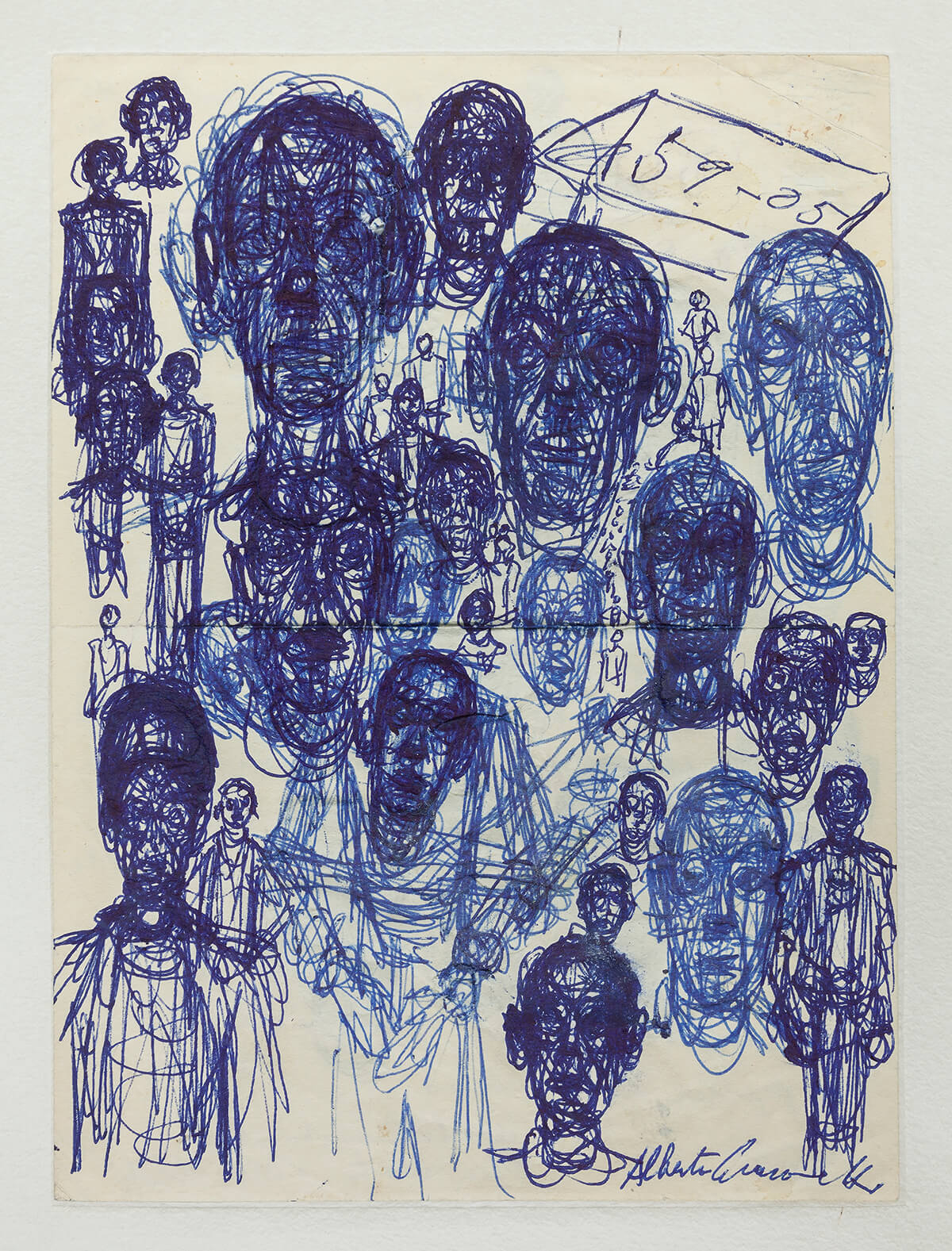

Thomas Jefferson, one of America’s founding fathers, was famously fond of Brane-Mouton, as Mouton Rothschild was then known, and shipped some over to the nascent United States in the 1780s. But it was Baron Philippe de Rothschild, the grandfather of Sereys de Rothschild, who elevated the wine to worldwide fame, first modernising the estate in the 1920s and insisting on ensuring quality by bottling all wines at the Château, and then asking a different celebrated contemporary artist to create a new label for Mouton Rothschild every year. The labels read like a who’s who of 20th and 21st-century art: among them are Jean Cocteau (1947), Georges Braque (1955), Salvador Dalí (1958), Joan Miró (1969), Marc Chagall (1970), Wassily Kandinsky (1971), Andy Warhol (1975), Keith Haring (1988), Lucian Freud (2006) and Gerhard Richter (2015).

Philippe Sereys de Rothschild with his daughter, Mathilde

The gardens of the Rothschild estate

The Baron’s daughter, Philippine, strengthened the link with the arts – she herself had been a celebrated actress, and married one of France’s most famous actors, Jacques Sereys – while growing the business; and so, on this evening surrounded by vines under a sky washed by the nearby Atlantic, with stars emerging from the fading blue, it seems entirely appropriate that her children are both honouring their mother and supporting the arts with this new prize.

Read more: 6 reasons to buy a Hublot Classic Fusion Bucherer Blue Edition

Certainly, the winners seemed delighted: “I am amazed,” Alice told me, with a big, dimpled grin, her perfect, wavy hair and immaculate outfit belying the fact that she had been dancing on stage minutes previously. She was sipping at a glass of Champagne shyly, as if it were a rare treat to indulge. “It’s a great thing for them to do, although I never thought I would win. It just helps make all the hard work worthwhile.”

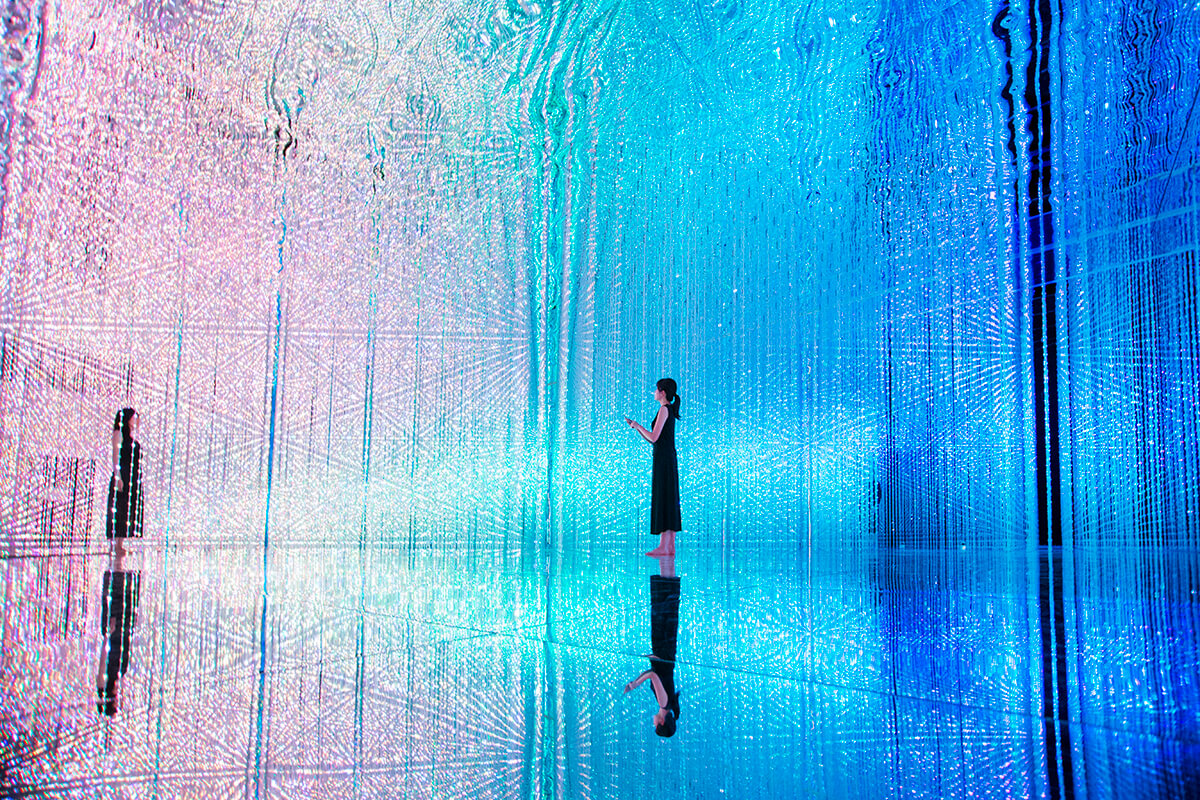

Dancers from the Ballet de l’Opéra National de Bordeaux perform at Château Clerc Milon

The next morning, I meet Philippe Sereys de Rothschild in a drawing room at Grand Mouton, the family’s traditional residence, a few hundred metres away in the heart of Château Mouton Rothschild. The room is square and traditionally decorated; four chairs have been placed facing inwards towards each other. Between two of them is an occasional table, on top of which has been placed a tray containing still and sparkling water, small bottles of tonic water, and two halves of a lemon on a saucer. Sereys de Rothschild walks in, erect, greets us and offers us drinks, before settling down in a chair, squeezing one of the lemon halves into his glass of tonic water.

The next morning, I meet Philippe Sereys de Rothschild in a drawing room at Grand Mouton, the family’s traditional residence, a few hundred metres away in the heart of Château Mouton Rothschild. The room is square and traditionally decorated; four chairs have been placed facing inwards towards each other. Between two of them is an occasional table, on top of which has been placed a tray containing still and sparkling water, small bottles of tonic water, and two halves of a lemon on a saucer. Sereys de Rothschild walks in, erect, greets us and offers us drinks, before settling down in a chair, squeezing one of the lemon halves into his glass of tonic water.

He was up, he says, until past 2am the previous night after the party ended, doing a debrief with his nephew Benjamin, who had helped organise everything. “Yes, last night Benjamin said, ‘We’ve got to do a debrief to know if it went well or not,’ and I said ‘OK, OK.’ So, we went through all the stuff that went well and didn’t go well, and it was the best time to do it because we had everything freshly in our minds. When people visit Château Clerc Milon they know it’s the family, they know it’s the Rothschilds. So, the standard is up there and you can’t disappoint them. Nothing is worse than disappointing people who have come to have a great evening and don’t have a great evening.”

All three of Philippine’s children were at the event; while Philippe oversees, Julien de Beaumarchais de Rothschild, his younger half-brother, is responsible for the collaboration between art and wine at Mouton, and gave a casual and touching tribute speech on the terrace the previous evening, after the formal speeches in the marquee led by Philippe.

It seemed to be quite a grand success for an event that is so young, I observe. “It is a young event and it actually happened much more quickly than I thought it would,” Philippe says. “The Foundation was created in 2015 and we did the first Clerc Milon prize in 2016. We wanted to start the foundation with something local. That was very important for us. Something local, something artistic and something linked to live performance. And all that was linked to my mother, because my mother was very close to the theatre, the Opéra de Bordeaux. Brigitte Lefèvre (president of the jury of the prize and a former administrator of the Opéra Garnier in Paris) really came in very quickly. I gave her a call one day; it was very interesting, she was outside on the street coming out of a documentary on ballet and I said, ‘I’ll call you back’ and she said ‘No, no, no, don’t call me back – what do you want?’

“I talked to her about the prize and everything and I said, ‘I’m looking for someone who could chair the jury.’ She said yes immediately, and it was in November 2015, so it was very, very quick. She was able to put the jury together quickly because after 20 years at the Opéra de Paris, she knows absolutely the whole planet in her world. So, the first prize was awarded in July 2016 and we were very happy.”

It was Lefèvre, he says, who had the idea of the prize specifically supporting young dancers and those who “cement the group together”. “And don’t forget,” he says, “the Foundation only has been going for three years. When we created it in memory of my mother, everyone knew she was very linked to the arts. As you know Mouton is also very linked to art: wine and art, art and wine. We knew we wanted a foundation carrying the name of my mother, and with an artistic purpose. That was very clear. So, we started there.”

Read more: Grand Luxury founders Ivan & Rouslan Lartisien on curating travel

A Harvard MBA, Sereys de Rothschild worked in the finance sector on graduating; in the late 1990s he was chief financial officer (CFO) of an Italian subsidiary of what is now the Vivendi conglomerate. He then ran a successful private-equity fund and created a high-tech investment fund. Was he always fated to take over the family company, I ask?

“No, not at all,” he says, very definitely. “I don’t feel that family businesses have to be run by families. Family business have to have family values, family principles, family ethics, family identities, yes. But that does not mean they have to be managed by the family, which is a completely different thing. We could have said, ‘Managers manage and the family is just there to define the values, principles, identity and culture.’ It was a choice, because it’s true that the family is very much linked to this company, and it was a choice that I made, to say that I was ready to spend much more time with the company, to make sure that we develop it the right way. There is a lot of development going on now, and I thought that the best way to ensure the development was done the right way was to implant myself more in the company. But it could have been different. I did many other things in my life before – some environmental projects, I managed a software company, I developed schools, I did a high-tech fund.

“But I’m not doing it alone, even if I’m managing this company with the objective of developing it, I’m doing it with the family. They are all on the board and we all decide together, and we all take decisions together and we all decide on the investments and whatever we want to do, together. I’m there to manage it and for the leadership, but they are there with me.”

Château Clerc Milon is a different kind of château with a modern vat house designed by architect Bernard Mazières

Is it different, I ask, managing a family business to running other businesses? “Well, although I’m completely conscious of the fact that it’s a family business, I really try to manage this business by asking myself, whenever I take a decision, is it good or bad for the company? Period. Because otherwise, you mix everything up. Don’t forget that we have 370 people working in this company, so what is important is to make sure that the company lives on and that I pass it on to the next generations. If I start thinking to myself I should do things differently because it’s a family business, then you make the wrong decisions. You have to make a decision, as a business decision, as a company decision.”

The Château Clerc Milon label features a pair of dancing clowns made of precious stones

Has his experience in the broader business and financial sector helped? “I think what has helped me is working with people with very different profiles. That’s been the most valuable thing. When you go from an environmental project to working with software engineers, working with more high-tech people, working with people in schools, you get used to going from one profile to another and to working with very, very diverse profiles. So, I can talk with people in the vineyards and I can talk with people on the market and I can talk to the people with the Ryder Cup [Mouton Cadet is the official wine of the Ryder Cup] or I can talk with the manager of the Festival de Cannes. They’re completely different types of people and the fact that I have had my own professional experience before has helped me to really make the difference between managing people with very different profiles. That’s probably one of the characteristics of the wine business, is that you really go from the vineyard up to the end of the line, who can be art collectors.”

The wine empire’s crest on the walls of the cellar

Over the past 20 years, wine has made a transition from being a drink enjoyed by those with the taste and means to acquire good bottles, to a trophy with, at the highest level, an ever-spiralling price. A case of Mouton Rothschild from a good vintage can cost as much as a new compact car, or a haute-horlogerie watch. Is Sereys de Rothschild in the luxury goods business, I wonder?

“No. I don’t really know which business I’m in,” he says. “In other words, in some ways we are in the luxury business, in some ways we are in the collecting business, in some ways we are in the limited series business, in some ways we are an agricultural product, in some ways we are in the tasting and drinking business. Where are we? I haven’t got the faintest clue. But that’s what makes it exciting and very difficult because we are not a luxury product, but we are in some ways a bit of a luxury product.”

Has China, which has been at the heart of the soaring demand for fine wines, affected the way the company does business?

“I would say it has affected it in the right way. What I like about the Chinese market is that it’s really a market of people who like wine, who drink wine, where wine has become part of their life. When they need to celebrate something they think about wine, which is very important, and it’s become a market of people who know wine well and who talk about wine in a very intelligent way. And don’t forget that Chinese people are very sensitive to education, and you cannot understand wine without having some sort of an education process. There is an initiation approach to wine and the Chinese people have understood that. And when you listen to Chinese people talking about wine, some are astonishingly knowledgeable. It’s real wine market in the long term, and a market of real, high-quality wine consumers.”

The wine world has evolved in recent decades. Mouton Rothschild and its fellow ‘first growths’ remain at the top of the ladder, but competitors have arrived from Napa, Italy and elsewhere, and the mid-market, where Mouton Cadet sits, has never been so crowded. What are the challenges facing the business?

“Staying at the top, which is sometimes more complicated than one thinks. The exposure that we have in the media has been multiplied [by the rise of digital media], which puts more pressure on us. It makes us more well-known, but at the same time if you make a mistake or if something goes wrong everyone will know it, so it exposes you much more. But at the same time, it’s very exciting because you’re much closer to the consumer. If they open the bottle and they don’t like it, you know. And 20 years ago, we could guess, but we didn’t know. So, you’re much more in contact with the end of the line, than we were before. Which actually makes things much more rewarding because you know what you’re there for. You know that you’re there to satisfy customers, much more than 20 years ago. So, it’s actually a very rewarding thing and the digital revolution is for me, very positive. The more I hear about the consumer and the more I know the consumer is happy, the happier I am.

Read more: Moynat unveils new collection of bags in London

“That’s the first thing. The second thing is that the market has become much more competitive, at all levels. In other words, it has become very competitive for Mouton Cadet because there are all the Italian wines, all the Australian wines, all the Chilean wines. So we have to fight for our space. But at the same time, it’s also true for cult wines and iconic wines. In other words, the first growths of 20 or 30 years ago were not quite alone, but the market was not too crowded. Today it’s getting more and more crowded. At the same time, it’s exciting because it’s a challenge and it puts pressure and you’re there to make things even better all the time.”

Château Mouton Rothschild has also been working to support the arts, in the form of the collections at Versailles, the legendary palace outside Paris. How do the two châteaux work in tandem, I wonder? “Mouton is linked to paintings, Clerc Milon is linked to dance. So that’s why we really have two very different things. Back at Mouton, because we’ve always been exposed to contemporary art, and it so happened that a certain number of artists that exhibited at Versailles – Anish Kapoor, Lee Ufan and Bernar Venet – also did the label for Mouton. We got in contact with Versailles and said, ‘Can we help you in any way with your contemporary art exhibitions?’ They were very enthusiastic and that’s what we decided to do. Without being immodest, Versailles is an institution, but so is Mouton in a way, although that’s not due to me, it’s been an institution since before I was born. Getting two institutions together that both represent in their own way the ‘art de vivre à la française’, I thought was… rather a great mix.”

There are sounds of activity coming from outside the room; Grand Mouton is gearing up for a celebratory meal with the jury. Sereys de Rothschild smiles as he shakes hands goodbye, and disappears through one of the doors for Sunday lunch with some leading lights in the arts, whom he is supporting. As I walk out along the perfectly raked gravel, and look at the immaculate lines of vine leaves alongside me, I reflect that the faces of the young dancers, the jury members and the patrons may be different, but everything they are doing is comfortably, commendably, consistent through the centuries.

Philippe Sereys de Rothschild on his favourite vintage of Mouton Rothschild:

“It’s difficult! I could mention the greatest vintages: 1945, 1959, 1961. The trouble is, I drank bottles of 1961 when I was much younger – 18 to 20. I drank a bottle of 1961 for my sister’s wedding, and another on her 10th wedding anniversary. Some guests came from England and one person was born in 1961 so we opened a bottle. Each time was different, so how can I say which was the best 1961? The magic about these wines is that they are never the same. They are always fascinating, they are always fabulous. So, if you ask me whether I prefer the 1945 or the 1961, I’d give you one answer today, and a different answer in five years.”

Discover Château Mouton Rothschild: chateau-mouton-rothschild.com

This article originally appeared in the Autumn 2018 issue. Click here to read more content: The Beauty Issue

The next morning, I meet Philippe Sereys de Rothschild in a drawing room at Grand Mouton, the family’s traditional residence, a few hundred metres away in the heart of Château Mouton Rothschild. The room is square and traditionally decorated; four chairs have been placed facing inwards towards each other. Between two of them is an occasional table, on top of which has been placed a tray containing still and sparkling water, small bottles of tonic water, and two halves of a lemon on a saucer. Sereys de Rothschild walks in, erect, greets us and offers us drinks, before settling down in a chair, squeezing one of the lemon halves into his glass of tonic water.

The next morning, I meet Philippe Sereys de Rothschild in a drawing room at Grand Mouton, the family’s traditional residence, a few hundred metres away in the heart of Château Mouton Rothschild. The room is square and traditionally decorated; four chairs have been placed facing inwards towards each other. Between two of them is an occasional table, on top of which has been placed a tray containing still and sparkling water, small bottles of tonic water, and two halves of a lemon on a saucer. Sereys de Rothschild walks in, erect, greets us and offers us drinks, before settling down in a chair, squeezing one of the lemon halves into his glass of tonic water.

Recent Comments