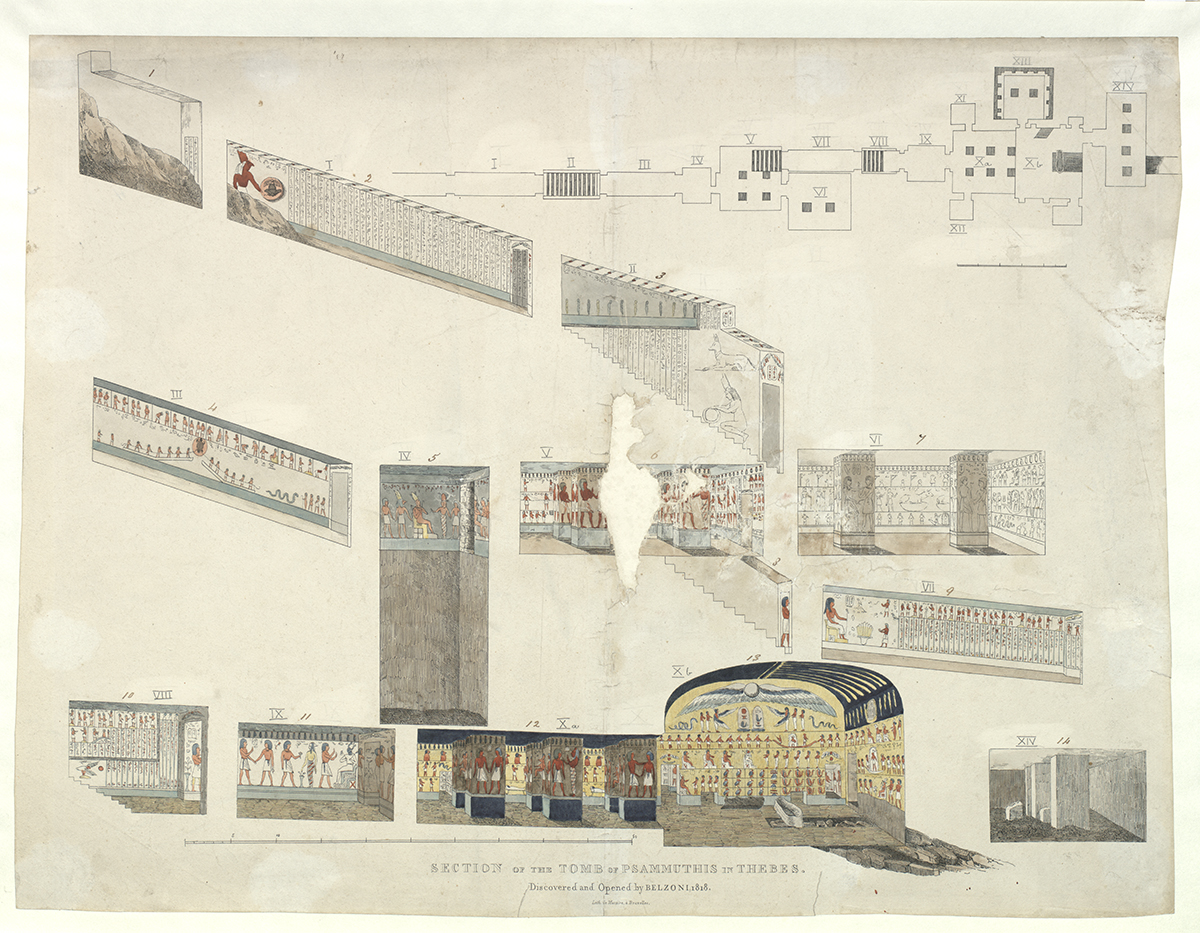

Installation view of Looking Up, Helaine Blumenfeld’s exhibition at Canary Wharf 2020. Photo © Sean Pollock

Helaine Blumenfeld OBE is best known for her large-scale public sculptures whose undulating, ethereal forms evoke a sense of fragility and movement, transforming the environments into which they are placed. In the light of a major exhibition of her works at Canary Wharf, Digital & Art Editor Millie Walton speaks to the artist about working intuitively, the importance of touch and how public art brings people together

LUX: What’s your creative process like? Do you follow a routine, or need a particular atmosphere to create?

Helaine Blumenfeld: I think I have quite an unusual creative process which has changed in a few ways over the years, but essentially, it has always been a process of trying to coordinate what I am feeling and thinking with what I am doing with my hands. That has taken a very long time. Now, when I go into the studio, I am able to disconnect from everything that is going on around me. Francis Bacon used to say that to release that [creative] energy he would either need to be drugged or drunk or both, to allow him to enter into a kind of trance state. I can go into that state, happily, without drugs. For me, it is a state of being. I go into the studio, close the door, and I am there.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

I don’t really look at the work whilst I am making. I take clay and I just keep adding to it or taking away. I have no plan of what I am going to do; I have no drawings. I just communicate with it, and that is how I have worked almost from the very beginning.

I had been working on a doctorate of philosophy, and I could never find the exact words I wanted, but when I made the very first piece in clay, I just thought: ‘This is just incredible! Did I really just do this?’ It was a talent that I had never understood I had, and yet it was so clear. Every piece I made in those early days was a wonder to me and then, we moved back to England from Paris and during the move, some of the pieces got broken. I thought I’ll never be able to do anything like that again.

Now, I do not have that feeling; I see it more as a process. There is a communication between what I am in terms of experience, and the work, and if one piece is interrupted or breaks or collapses, the next piece will follow it.

Helaine Blumenfeld with one of her sculptures. Photo © Sean Pollock

LUX: You mentioned that you were studying philosophy – when did you start making art?

Helaine Blumenfeld: I always had these amazing dreams that I could never seem to translate. The only way that I knew was words, and yet, to have an incredible dream and then to use words is so bizarre because it is a completely different language. For a while, philosophy seemed like the right method for my expression, but I was never satisfied. When I discovered sculpture and began to understand what very simple forms could communicate, I decided I wanted to be a sculptor.

I think that being an artist is not just about having something to communicate, but also finding the right way to communicate it, and if you don’t, you can be frustrated. Discovering sculpture opened up the whole world to me.

Helaine Blumenfeld, Exodus V, 2019, Photo © Henryk Hetflaisz

LUX: Was lockdown a creative time for you?

Helaine Blumenfeld: Well my main studio is in Italy, so I have not been able to go back at all. In fact, because I had this very big show [Looking Up] in Canary Wharf, I was meant to go back before we had finished the installation to bring back two pieces that I had not quite finished, but my husband said not to go. It was lucky that he did because otherwise I would have spent the whole lockdown without my family.

In the end, we managed to get the entire show of 40 pieces up at Canary Wharf just two days before lockdown. The opening, which didn’t happen, was intended to be the day of lockdown. When I went back to Cambridge, I was suddenly aware of the virus and what it was doing, which I hadn’t been, and the first two weeks were very anxious. I thought I would have contracted it because I had been working with so many people, including one of my assistants from Italy who had come over, and whose wife had the virus. But after that period, and I think a few artists will tell you the same, it was one of the happiest periods in my whole life. No pressures from the outside world, no commitments, no engagements, no travelling back and forth to Italy, which I normally would do for two weeks here and two weeks there. I was with my husband all the time which I hadn’t been since the beginning of our marriage. And I had clay; I had all the clay I needed. I was working, and I have done more work in the period of lockdown than I have in the last three years I think. So, yes it has been immensely creative.

Read more: Confined Artists Free Spirits – artists photographed in lockdown by Maryam Eisler

LUX: Do you ever start a sculpture and decide to abandon it if it’s not working?

Helaine Blumenfeld: There are different ways of working. Someone like [Constantin] Brâncuși, who I admire enormously as an artist, was held back by his own sense of perfection. Each piece had to reach what he wanted, and it never did, so he would have to abandon and try again. He was tied to certain ideas, whereas I believe that each piece is as good as it can be. I work through the idea rather than trying to get it right in that particular piece. As I said, I never have a clear idea of where I am going or a vision that I need to achieve; the vision comes in the piece.

Helaine Blumenfeld, Taking Risks, 2018, Photo © Henryk Hetflaisz

LUX: That sounds very liberating.

Helaine Blumenfeld: In sculpture, the gesture can be completely yours. When I am working, I don’t look at what I’m doing I feel it intuitively as it happens. Very often when I am in Italy, I finish something in clay and I cover it and wrap it with wet cloth, and then when I go back, I have no idea what I am going to find. I have never seen it objectively or critically, I have just seen it intuitively. When I do unwrap it, then sometimes I will say ‘Oh, that doesn’t work’, and I won’t go on with it. At that moment, I am really seeing with a critical eye. It’s like seeing your lover in another way from the corner of your eye or a different angle which allows you to seem them objectively for a moment. When I come back to the work, I am able to see it objectively, and at that moment, I know intellectually whether or not it is working.

It is a bit of a different process if I want to do a large piece, however, because when I am working, I have no armature or inner support system. If I had that I would know exactly what I was going to do because the inner structure would dictate what I was going to make. Without that structure, the sculpture is initially incredibly fragile and if it is going to last, I need to have it cast in plaster quickly. Then, when I know the forms, I don’t feel the same resistance to having an armature. At that point, I have an assistant who will mechanically enlarge the piece for me with a proper armature and leave it in a rough state for me to take over. It does happen when I think a piece is very good, but when the scale changes, it doesn’t work. I think that is a mistake that certain sculptors make, thinking that everything can be large when some pieces work better on a small, intimate scale.

Helaine Blumenfeld, Exodus IV, 2019, Photo © Henryk Hetflaisz

LUX: What role do you think public sculpture can play in urban environments such as Canary Wharf?

Helaine Blumenfeld: I think that sculpture, in general, in a public place, creates a private space for people to enjoy. In a way, it creates a space that people can claim ownership of. My idea is to somehow mediate between the personality and the mechanism of a landscape and to create something that is personal and that people can relate to. For example, my first public commission was in centre of a walkway, and I went around and had a look at how people used space. There was a gigantic sculpture there that people would walk around to avoid. Somehow the massiveness of it mirrored and competed with the architecture in a way. So, I decided to do a sculpture in five pieces, that people could walk in between and interact with that would be on a human scale, and it was such a success.

Helaine Blumenfeld, Fortuna, 2016, Photo © Sean Pollock

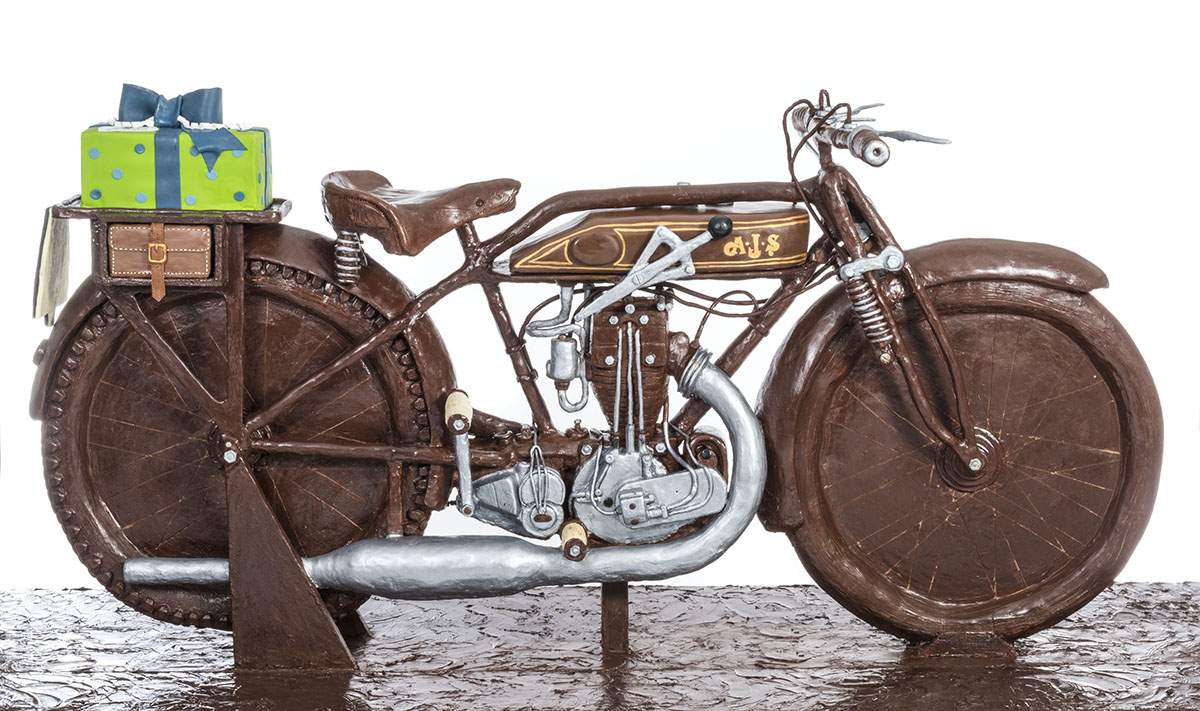

My piece Fortuna, which was put up in 2016, was originally meant to go to the new area of Wood Wharf. When it was finished, it was temporarily put into an area in Jubilee Park, and in a very short space of time, that area in the park was overwhelmed with people coming to interact with the sculpture. When word got around that it was going to be moved, people were horrified. That particular area was meant for changing exhibitions, but the piece remains there and people still go to see it.

Read more: American artist Rashid Johnson on searching for autonomy

Also, in that same area, there is a sculpture called Ascent. After lockdown when you could have groups of six, I went back to see the piece and they had made circles on the ground around it so people could sit in those circles and know that they were social distancing. On that lawn there were six different circles of people sitting. They obviously knew each other and they were celebrating something. I had gone there because wanted to photograph the piece. When I arrived, a man looked at us and said ‘Oh, I see that you want to photograph Ascent‘ which was amazing, that he even knew the name. He said ‘Let me show you the best view!’ He took me round to the side and in fact, it was my favourite view. My friend told him that I was the artist and he knew my name too. He announced to the group of people in their circles: ‘This is the artist’. Every person in that area stood up and clapped. It was like it had been an opening. He told me that he came to the sculpture every day and that it was his point of light in the darkness, it gave him some hope that things could be better. It was an amazing experience for me.

Helaine Blumenfeld, Flight, 2019, Photo © Sean Pollock

LUX: Speaking of intimacy, you’ve said before that you like people to touch your sculptures. Why is that important for you?

Helaine Blumenfeld: Oh, I think it is vital for people to touch the work. I think we do not touch enough in our society. So much of our feeling and experience comes from touch. As babies, our world is all about touch, but we are are losing that. Very early on I had a show with people from LightHouse for the Blind, and all they could do was touch. You would be astounded at what people could feel from touching a sculpture, another level of understanding, from just their hands.

You can see that people are entering into the sculptures where the bases have worn away. I often ask the children who are sitting inside, ‘What are you feeling?’ And they say something like, ‘I am in a secret forest and I am protected from all the things around me.’ It is lovely to see how a sculpture encourages imagination.

Often at public exhibitions, whether it is in a cathedral or in Canary Wharf, I see people discussing with each other, and they don’t know each other. ‘What do you see in it? What are you looking at?’ Not only does art introduce a huge audience to beauty, it is also allows people relate to something outside of themselves, it introduces them to another realm. I think that is an incredible way that art brings people together.

LUX: One final question: what’s inspiring or interesting you at the moment?

Helaine Blumenfeld: It is hard for me to use the word inspiration; I feel incredibly moved. When an artist dreams a dream that is so deep within his own being, it is not just his dream, it is not just his pain, it is universal. That is what I hoped I was doing before, it was coming from within, but much of what I am doing now is coming from without. I am thinking about how people are trying to connect at this time, to reach out and see the perspective of other people. There is a much greater effort because we are all in this together. It has broken down that sense of isolation which I felt was leading to the precipice. So instead of expressing something deeply personal, I am trying to feel something that effects everyone. I think that is where the new work is going.

‘Looking Up’ by Helaine Blumenfeld runs at One Canada Square until 6 November 2020 and throughout Canary Wharf until 31 May 2020.

For more information visit: helaineblumenfeld.com

Recent Comments