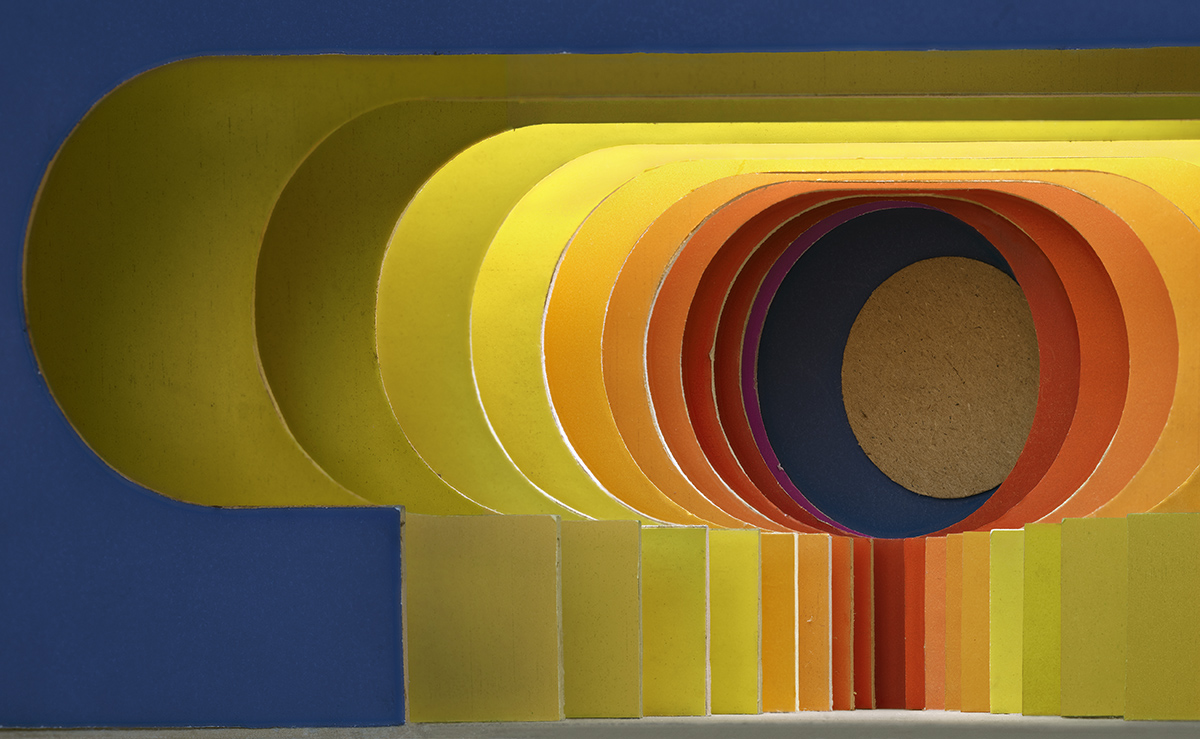

‘Big Bang Fountain’ (2014) by Olafur Eliasson

The Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson famously brought the sun to Tate Modern. He is now returning for a major retrospective this summer. He talks art, cuisine, and slumber with Christopher Kanal

Olafur Eliasson

“I am incredibly happy about the whole thing,” Olafur Eliasson explains of the major retrospective of his work at Tate Modern in London that opens in July 2019. With ‘Olafur Eliasson: In real life’, the revered Danish- Icelandic artist returns to Tate 16 years after his ground-breaking The Weather Project famously filled the gallery’s Turbine Hall with the illusion of a sunset that was as eerie as it was sublime. Hazy memories of basking in the dazzling surreal sunlight mask the fact that The Weather Project has been one of the most critically acclaimed art installations so far this century and was experienced by over two million people.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

“We were lucky to warm up with the iceberg project,” Eliasson says with a gentle laugh. In December 2018 Eliasson staged a feat that could have come straight out of an Icelandic saga, but which had a very contemporary and urgent environmental message. The Scandinavian artist hauled centuries-old icebergs from Greenland to the banks of the river Thames to demonstrate the effects of climate change. Twenty-four icebergs, originally from the Nuup Kangerlua fjord in south-western Greenland, and weighing up to six tonnes each, were placed in a circle outside Tate Modern and another six were put on display in the City of London as part of Ice Watch, a collaboration with award-winning Greenlandic geologist Minik Rosing. People gawped at, touched and even tasted the ice. “I’ve been studying behavioural psychology, and looking into the consequences of experience,” says the artist. “What does it mean to experience something? Does it change you or not change you?” When Ice Watch London debuted, Eliasson and Rosing pointed out the sobering statistic that 10,000 blocks of ice such as these are falling from the ice sheet every single second.

‘Beauty’ (1993) at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 2015

‘Ice Watch’ (2018) by Eliasson and Minik Rosing, outside Tate Modern, London

Of course, Eliasson is not just celebrated for The Weather Project and icebergs. His varied works span not just temporary public art projects such as The New York City Waterfalls (2008) and large civic projects, such as the design of the façade of the Harpa concert hall and conference centre in Reykjavík (2013), but also small art projects and social enterprise endeavours. For Glacial Currents (2018) Eliasson created a group of watercolours produced using ancient glacial ice fished from the sea off Greenland. The ice was placed atop thin washes of colour on paper. As the ice gradually melted it displaced the pigment to produce extraordinary shades.

The studio’s Little Sun project, meanwhile, provides clean, affordable solar energy and light through a simply designed LED solar-powered lamp. “It brought me back to being a student,” he says of envisaging the design. “This is of course the greatest thing that you are not in fact getting older but you are getting younger.” The Little Sun lamp, which was launched in 2012, produces up to five hours of bright light. Over half a million lamps have been distributed to off-grid communities in 10 African countries.

Read more: Why you should be checking into L’Andana in Tuscany this month

The prolific 52-year-old artist is also an avowed foodie. So much so, that his Berlin studio has a professional kitchen run by his younger sister Victoria Eliasdottir. “This experimental kitchen is very much part of the life of the studio where dining together and sharing ideas has become enormously important for us,” he says. “The food in the studio is more family style where we put the pots on the table and we eat out of them,” he says, adding, “It’s not French service.” In late summer 2018, the siblings opened Studio Olafur Eliasson (SOE) Kitchen 101, a temporary restaurant/gallery by Reykjavík’s harbour and it became a hugely popular hangout. “Really great food always has a frictional element because it reminds you of all the not-so-great food you have eaten,” Eliasson says. “Good food is always on a trajectory and a journey. A great cook shapes a taste just as an artist shapes a sculpture. In that way great cooking is a very sensual, alchemic activity.”

Façade of Harpa Reykjavík Concert Hall and Conference Centre (2005–11)

Eliasson’s studio is in a former brewery and chocolate factory in Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin, an area that was once part of the city’s Soviet Sector during the days of the German Democratic Republic and a haunt of intellectuals, artists and East Germany’s gay community. Eliasson splits his time between Berlin and Copenhagen, where his art historian wife, Marianne Krogh Jensen lives with the two children they adopted from Ethiopia. The huge four-storey studio is home to a collective of around 80 artists, architects, engineers, developers and researchers. Each floor is a distinct hive of creative activity. Eliasson is certainly not the first artist to run a collective. Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York springs to mind, but Eliasson and his studio work very much as a collaborative team – he likes to call it ‘The Lab’. He is, however, no ringmaster: “I have always insisted on an open and transparent studio. There is no mystical, magical authenticity idea in keeping me as a kind of mythical figure.”

One of Eliasson’s most celebrated designs involved a collaboration with Copenhagen- based architectural firm Henning Larsen and Icelandic studio Batteríið Architects. Inspired by basalt crystals found in the geology of the dramatic Icelandic landscape, Eliasson’s glass façade design for the Harpa concert hall in Reykjavík scattered reflections of the surrounding harbour, the fluid sky above and the looming Mount Esja across the bay. By night Harpa is a glittering spectacle of light. The building is in a constant flux of visual metamorphosis, which constantly alters perceptions. No one minute is the same. “The object is not necessarily the most interesting part about art, says Eliasson. “It is what the object does to me when I look at it or engage in it that is actually interesting. You are somehow provoked into a more negotiating role because you think, ‘What am I looking at?’ Then you are also more likely to enquire, ‘Well, what does looking actually mean and why am I seeing things the way I see it?’”

‘Waterfall’ (2016) at the Palace of Versailles

Eliasson was born in Copenhagen but returned often to Iceland after his parents separated when he was eight. His father was a cook on fishing boats as well as an artist, his mother a seamstress. Growing up in Scandinavia, the varying light, storm winds, bible-black winter nights, crystalline ice and vibrant norðurljós (northern lights) all infused Eliasson’s imagination. During the long summer holidays of his youth, Eliasson returned to Iceland to spend time with his parents and grandparents. The Icelandic landscape has been a lasting source of inspiration to him, particularly in its unique power to challenge how as an artist you interpret place and space through its beautiful yet unfamiliar and primal character. Eliasson tells me he likes to sit in his Reykjavík studio for inspiration because of the extraordinary quality of light in Iceland due to the island’s high latitude. As a boy he recalls that during the oil crisis of the 1970s, the Icelandic government used to switch the power off at 8pm to save energy, announcing the blackout by ringing the church bells. Eliasson fondly remembers the long, haunting twilights of dense colours and long shadows that were the only source of light.

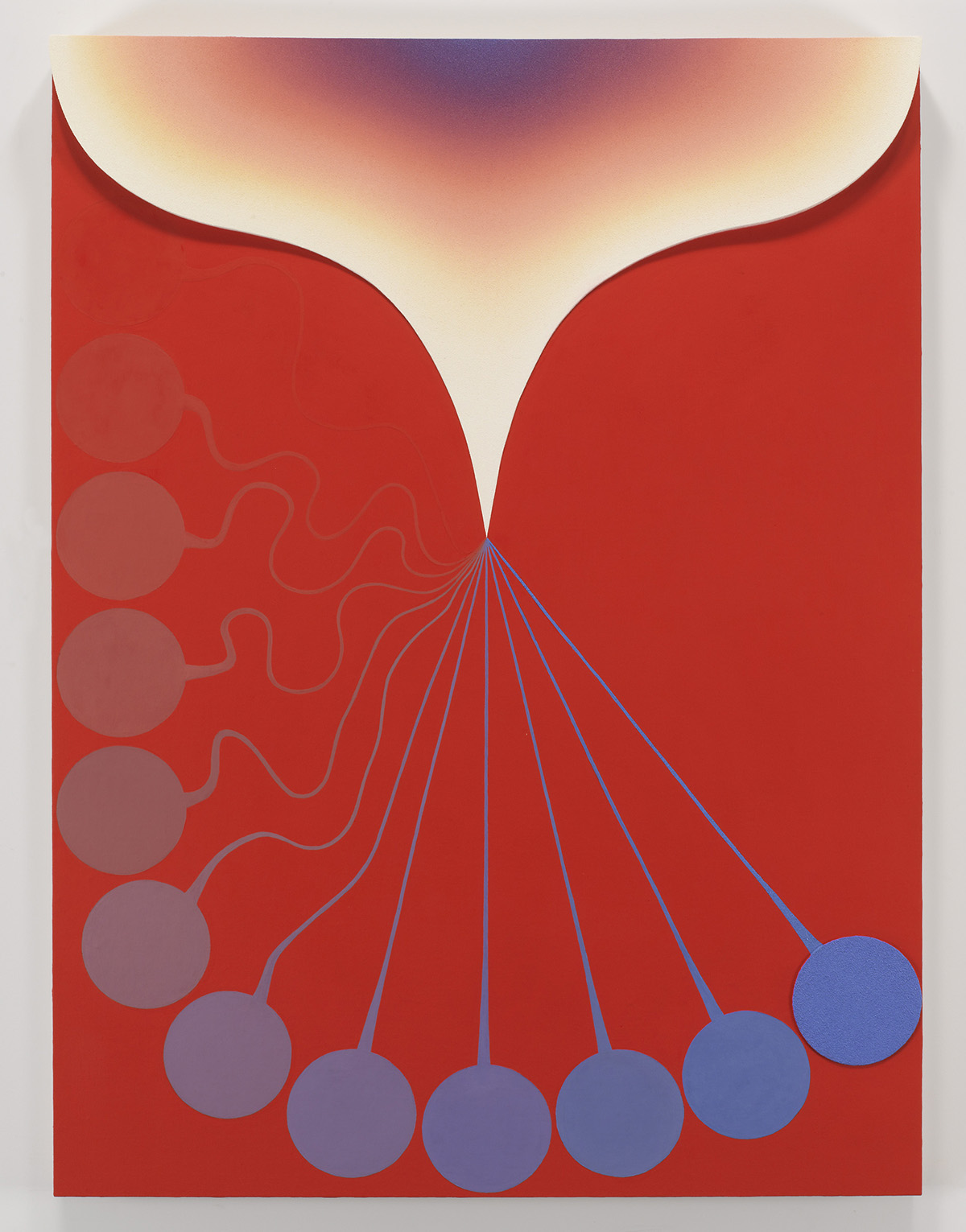

‘Umschreibung’ (2004) at KPMG Deutsche Treuhand-Gesellschaft, Munich

At 15 Eliasson had his first solo show, of landscape drawings in Denmark. “My father was an artist who influenced me and both my mother and him were more focused on me feeling successful with what I did,” he reflects. “When I did crazy doodles, they would say, ‘This is a great drawing’ instead of ‘This is not a house’. My father would say, ‘Why don’t you just fill in the blanks and it may end up being a dog or cat?’ I realise now that this was not so bad because it gave me the confidence that something abstract actually had the potential of becoming meaningful. This is something I have carried throughout my life.” After studying at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Eliasson moved to New York and worked for the Canadian minimalist artist Christian Eckart in Brooklyn. In the mid 1990s, he moved to Berlin, then a new cultural frontier following the fall of the Wall.

Read more: 6 Questions with renowned British art collector Frank Cohen

During the financial crisis Eliasson had an idea that he could save the Icelandic economy by buying all the grey sheep running around the country. Grey sheep are less popular than black or white sheep with farmers as they are harder to spot in the autumn, when they are rounded up and brought down from high mountain pastures where the grey sheep are indistinguishable from the rocks and the ground. “As an idea, a grey sheep is indecisive, it is a making-your-mind-up-as-you-go kind of sheep,” he says, with a bit of mischief. Eliasson’s plan was to farm these sheep in the harsher northern fjords where they would graze on wild berries and grasses. “The southern sheep are generally grass-fed sheep fattened up like turkeys in Kentucky,” he points out. “The texture of the wilder sheep meat is a lot darker, like deer.” Eliasson reveals he envisaged making his own version of Icelandic blóðmör blood sausage but with a North African twist, adding dates, onions, raisins and truffle oil. “People thought I was insane,” he says. “I guess Icelanders are not so much into North African food considering the history of the Tyrkjaránið pirate raids by the Barbary corsairs on the Vestmannaeyjar [a small archipelago off the south coast of Iceland] in 1627. I realised that I had probably contributed to the financial crisis rather than saved it but I tell you this sausage was amazing!”

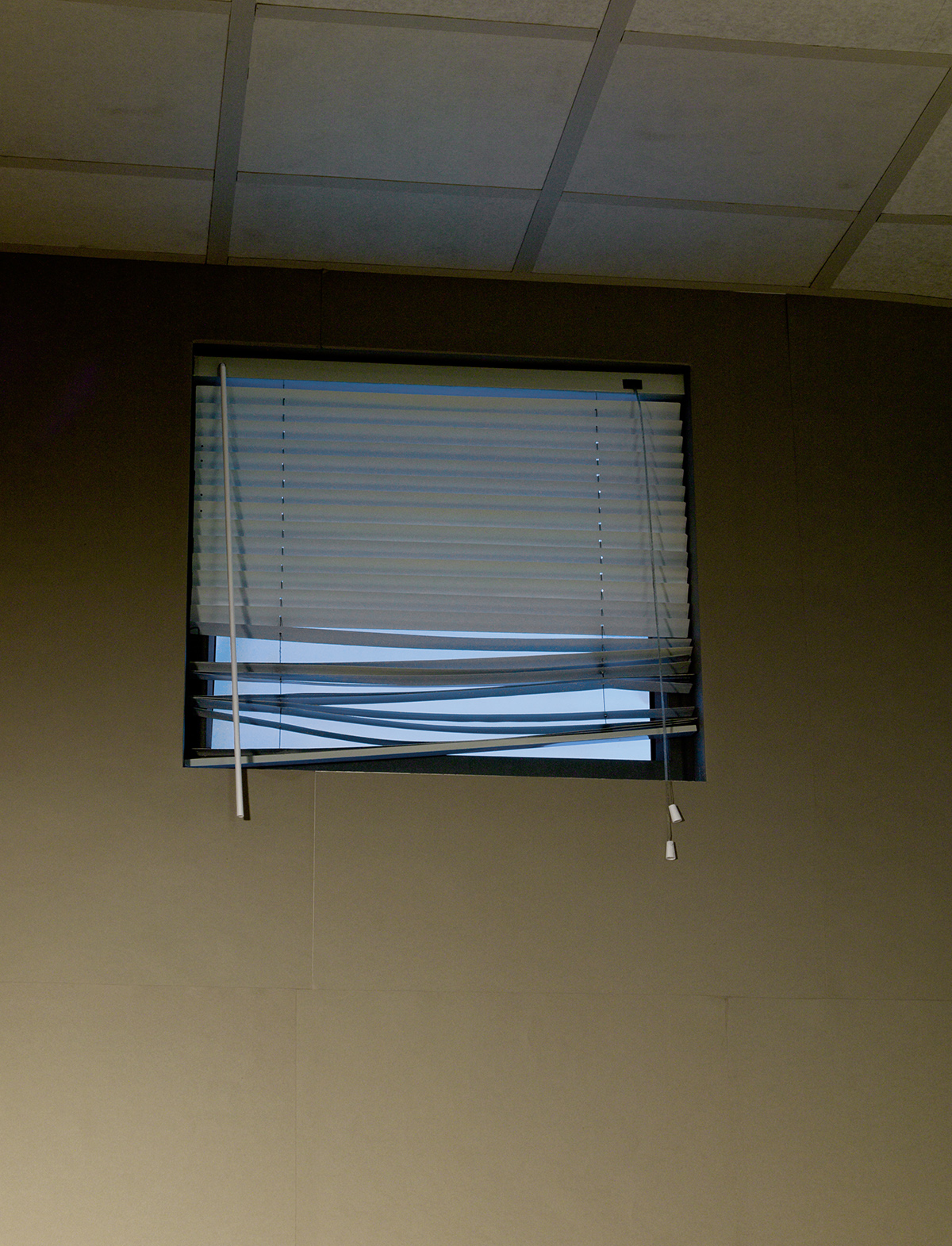

‘The Weather Project’ (2003) at Tate Modern, London.

Amongst the sketches, models and large collection of vintage light bulbs in Eliasson’s studio there is an archery target. For inspiration, the artist will often pick up a bow and shoot an arrow into it. A lucky bulls-eye indicates a ‘yes’. It reveals Eliasson’s particular approach to his work. “I love supporting the people around me who I believe in and trust,” he says. “I learn so much from them, so it is a nice exchange. It’s a great luxury to be working with chefs, scientists or politicians. As long as I don’t start to cook or make science. I get stressed when I boil an egg.”

Answering the call

“This is a kind of profession you end up in,” says 29-year-old Victoría Elíasdóttir, who Condé Nast Traveller hailed in 2016 as one of the ‘10 Young Chefs to Watch’. “I kind of did,” she adds but then adds, “No, I kind of didn’t.”

Born in Denmark but raised in Iceland from infancy, Elíasdóttir grew up with food. After travelling around South America in 2007, she returned to Iceland and went to college. “Society said that being a chef was bad for your body, it’s not family friendly, you drink a lot and do drugs,” she says. “I tried graphic design and psychology. I started all these things but I always ended up talking about food, talking to my classmates and teachers about what I cooked yesterday, what I was going to cook tomorrow. In the end one of my classmates said ‘Why don’t you just give in?’”

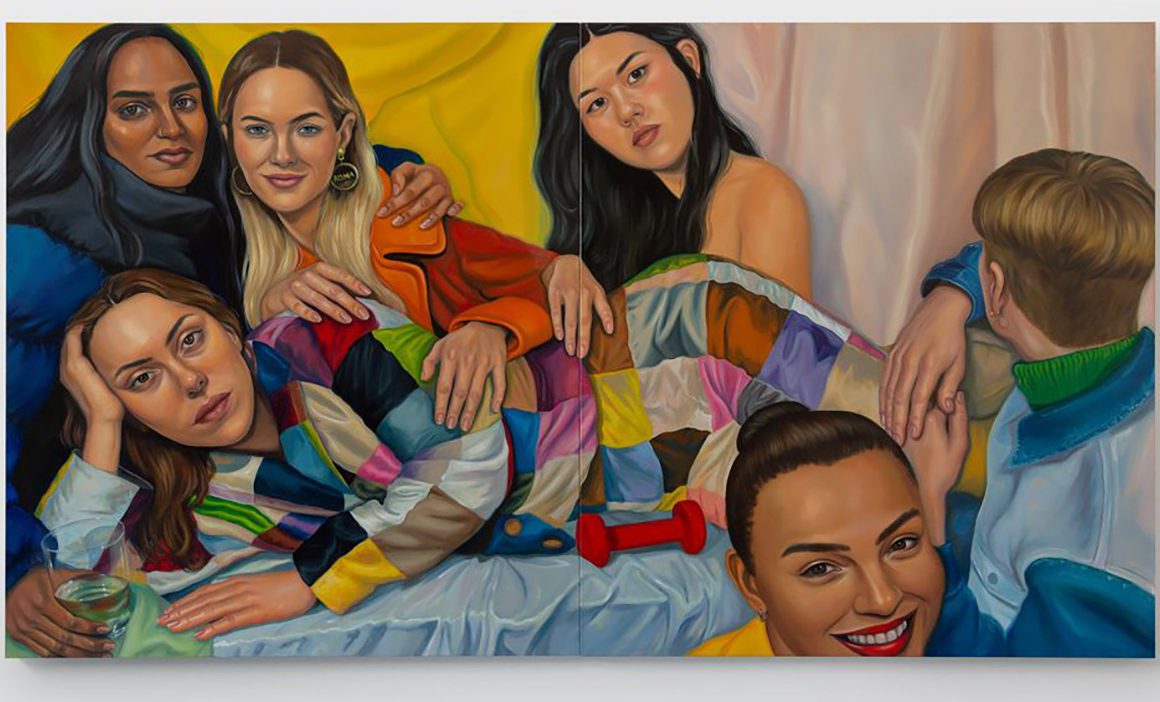

‘Your Spiral View’ (2002), installation view at Fondation Beyeler, Basel

Elíasdóttir went to chef school in Reykjavík and initially found it tough: “My initial experience of being a chef was not very encouraging. On the other hand, I have always been drawn to things that kick up the adrenaline in a way.” After graduation she worked as head chef in a small summer hotel in southern Iceland, an idyllic place by a lake filled with wild trout and which grew its own tomatoes and cucumbers. There followed a stint at Chez Panisse in California under the eyes of culinary visionary Alice Waters before ending up in Berlin and helping run her big brother’s studio kitchen.

In 2015 she opened Dottír, a temporary restaurant in Berlin’s Mitte that occupied a building that had been a Stasi surveillance centre. It was a hit, with inventive dishes such as beet-infused salmon served raw and North Sea cod with Jerusalem artichoke cake, creamy sauce and trout roe. “Beetroot has been something that has been with me from as early as I can remember,” Elíasdóttir enthuses. “When I was child my mother used to serve it to me on a piece of rye bread with liver paté.” She also has a fondness for lakkrís (liquorice) and uses it when she can.

Elíasdóttir also caters for high-end corporate events. She recently created a seven-course vegetarian menu for Mercedes-Benz. “Everyone was a bit sceptical but afterwards I had comments from these big men, used to lobster and meat dishes, saying, ‘I don’t feel like I missed anything!’”

Avoiding the tired New Nordic cuisine label, the heart of her cooking is avowedly rooted in Scandinavian gastronomy. Think simple fresh seafood, herbs and regional, seasonal produce. “We have great farmers here in Iceland,” explains Elíasdóttir.

Sci-fi by design

Acclaimed French director Claire Denis’s new film, the sci-fi drama High Life, boasts a spaceship designed by Olafur Eliasson. Denis, best known for her widely praised films including the existential Foreign Legion drama Beau Travail (1999) and avant-garde vampire story Trouble Every Day (2001), has made her first English language film also her first foray into science-fiction.

High Life stars Juliette Binoche and focuses on a group of miscreant astronauts on a mission to reach a black hole in search of an alternate energy source. Eliasson’s involvement is his first work for a feature film but his second collaboration with Denis – together they made short film Contact in 2014 that explored themes of black holes and abstraction. Denis and Eliasson’s mutual fascination for these phenomena is evident in High Life, a story that Denis has been nurturing for 15 years. High Life opens in spring 2019.

‘Olafur Eliasson: In real life’ is at Tate Modern, London from 11 July 2019 to 5 January 2020. For more information visit: tate.org.uk and olafureliasson.net

This article was originally published in the Summer 19 Issue.

Recent Comments