Jonathan Siboni, founder and CEO of Luxurynsight, and Richard Collasse, former CEO of Chanel Japan

Richard Collasse, working with Karl Lagerfeld, built Chanel Japan into a game-changing luxury business in the 1980s and 90s. Here, the Japanese-speaking French polymath, who is a celebrity in his adopted country and as active as ever, speaks with Jonathan Siboni about the differing nature of luxury across different markets, how luxury is a dream, and how ADHD can help you stay at the top. Moderated by LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai

Darius Sanai: Richard, you entered Chanel Japan before the descente du temple, the democratisation of the luxury sector in the 1990s. What are your recollections of that time? Does it feel like a different industry?

Richard Collasse: Absolutely. Japan was a leader: it was not yet number one but became so a few years after I joined in fall 1985. And Japan is a country that has cycles: it goes down, then comes back. When I started, Japan could only rely on local customers; there was no interest among tourists, because the prices were higher than any other countries in the world. We were probably the first – the luxury industry in Japan, I mean – to work on what today we call ‘consumer care’. We were very advanced. So, it was a very different era.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

Jonathan Siboni: At that time with Chanel, it felt like we were at the beginning of an adventure that turned into empires in an incredibly short time. Japan was like learning from the best school because of the way the luxury market was developed in Japan – not just because Japan only had local customers, but because the local customers were Japanese. I think the industry grew from this attention to detail, quality and customer care, don’t you think?

Richard Collasse’s career has been rooted in Japan, Asia’s first prominent buyer of luxury goods and one of the biggest luxury markets in the world

RC: Absolutely. Customers, especially in Japan, have always been demanding. In the Chanel cosmetics business, the caps of the lipsticks were black lacquer: not easy to keep clean and always scratched after a couple of uses. We told the French there are machines in Japan to do the lacquer work, so they got one and began to understand what quality was really about. It was still very artisanal in Japan, about detail and quality, because we only had the Japanese for customers; we didn’t rely on other people to come and buy.

JS: Some of the challenges that the Chinese market is facing today – for instance, people being bored of luxury goods – reminds me of Japan 25 years ago, when people were making a lot of money and spending it on luxury, and then there was, as you say, a cycle. But some brands such as Chanel continued to grow because they changed and reinvented themselves. Are there some lessons that can be applied from Japan 25 years ago?

RC: I think the problem with China is slightly different to the one we had – our issue was not that people were fed up with the brand, but with our attitude. We were taking good care of loyal customers, but with new ones we were a little arrogant.

Also, people didn’t have access to fashion shows and complained that, even if you were a good customer, they were behind closed doors. We had trunk shows going around Japan – small fitting rooms where ladies would try outfits and buy like crazy – but at the boutique, there were no products any more, because they had been sold during the trunk shows.

Jonathan Siboni speaking as founder and CEO of Luxurynsight, a luxury data and strategy company

So I stopped those. I decided, first, our boutiques should be our showplaces, and I made our boutiques very beautiful. Second, we told our salespeople that arrogance is not an attitude, and third, we did an open-air fashion show, where anybody who wanted to come could. In May 2000, Karl Lagerfeld came with 100 top models and showed the haute couture and the prêt-à-porter of the season. Our sales came back right away. We told our customers that Coco Chanel did not create fashion for an elite, quite the opposite: she created fashion for the women who wanted to work. So we did that and we had a new start.

JS: Japan in the 1990s had also undergone economic difficulties but, ultimately, 30 years later it is completely different. I still believe, however, that the only brands that will do well are the ones that reinvent themselves to stay at the forefront of cultural exchange.

Read more: Binith Shah and Maria Sukkar on UMŌ’s ultimate luxury

Speaking of cultural exchange, I’ve always wondered what it means for you, as a French person, to be more famous in Japan than at home, and to get to this level of mastery of a culture that is not yours. When you’re in Japan, do you feel at home?

RC: Well, I was already fluent in Japanese, but people started to know me when I created Givenchy Japan, back in the late 70s. We did the 30th anniversary of Givenchy at the Japanese national television network, which is not allowed to make a brand statement. I convinced them that Givenchy was not a brand, but a part of French culture. And people started to say, who is this guy? But I have a strong power of persuasion. So when I started at Chanel, I already had that aura and it was easy for me to work with our people.

Richard Collasse with his team at Chanel Japan, where he worked from 1985 to 2023, most notably as CEO

We were inventing everything in Japan – the intellectual wealth of the company was that we had different people on the markets. Today, you have managers, who have graduated from the best fashion places, but we are losing the leaders. I’m not talking about Chanel specifically, but the industry as a whole. Because of exactly that: it has become an industry. When I started, it was still artisanal.

JS: What I found fascinating in the golden days of luxury was that the best businesspeople I met were creative and business driven. They would never encroach on a creative director’s decisions, they would believe that everyone has their own role, but they were business creative. That’s something I find fascinating because as a creative you want to be creative, but you also have to reinstate the boundaries of your role.

RC: Yes, I would never have been able to say to Karl [Lagerfeld], ‘We need this kind of jacket because this is a trend that’s just come in.’ That’s not the way it works. But he appreciated my creativity in a different way. With this fashion show back in 2000, nobody dared to go to Karl to tell him it was my idea, until a young PR lady went to see him and, against all odds Karl said “Let’s do it.” It was out of the question to step into the creative territory of the products, because I didn’t have the know-how. But creativity also meant expressing ourselves in the business side of things. And I started to write. That’s when Karl Lagerfeld started to appreciate that I was also a creative.

DS: If the “you” from 40 years ago arrived in Japan now, would your skillset be relevant? Would you become president of Chanel Japan today or would they need someone else, given the way the industry has changed?

“I think my capacity to do different things almost at the same time is because I have passion” Richard Collasse

RC: I don’t know if I would be relevant; we live in a different time. Today, they need managers who can develop the business within budget and who are technicians. I was not a technician. I think the company decided that the managers of my generation were not needed any more.

JS: One thing that strikes me is that luxury is not a business, it is an industry based on culture, marketing, exchange, as well as products. The product is a dream, in a way: I don’t think people buy a $10,000 bag because it holds things better. Somehow, business creativity was a bridge between these worlds of corporation and the real world.

Read more: Omega CEO Raynald Aeschlimann on the watch industry

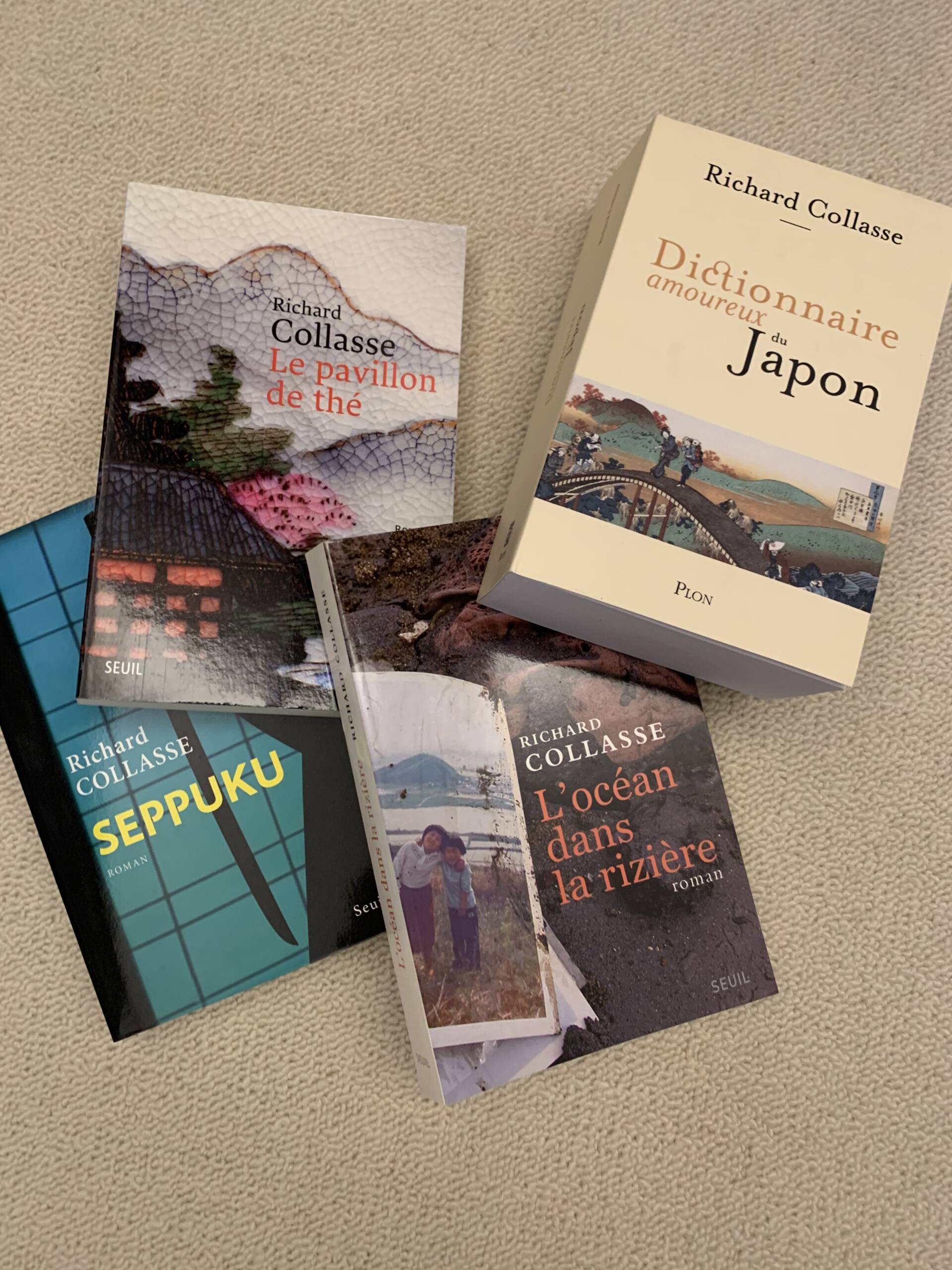

That’s why I wonder – how can Richard find time to do what he does? When I was a student and emailed you, you would reply within 10 minutes, in the middle of the night. How did you manage to do so many things at the same time? Because there was Chanel, and you were also writing books.

RC: I am what you would call today ADHD. I cannot stay still for one minute. I think my capacity to do different things almost at the same time is because I have passion. If you don’t have passion, you’re not going to do that. I have a power of concentration and I am also lucky that I don’t need much sleep – if I needed 10 hours I probably wouldn’t be able to do all these things at the same time.

I’m 72 now and probably as busy as I was at Chanel. But for my 50 or so years in business I always had an assistant, and now I am discovering I don’t know how to book a train or manage my schedule! They allowed me to get rid of all these banal things, just so I could concentrate on the things that mattered to me.

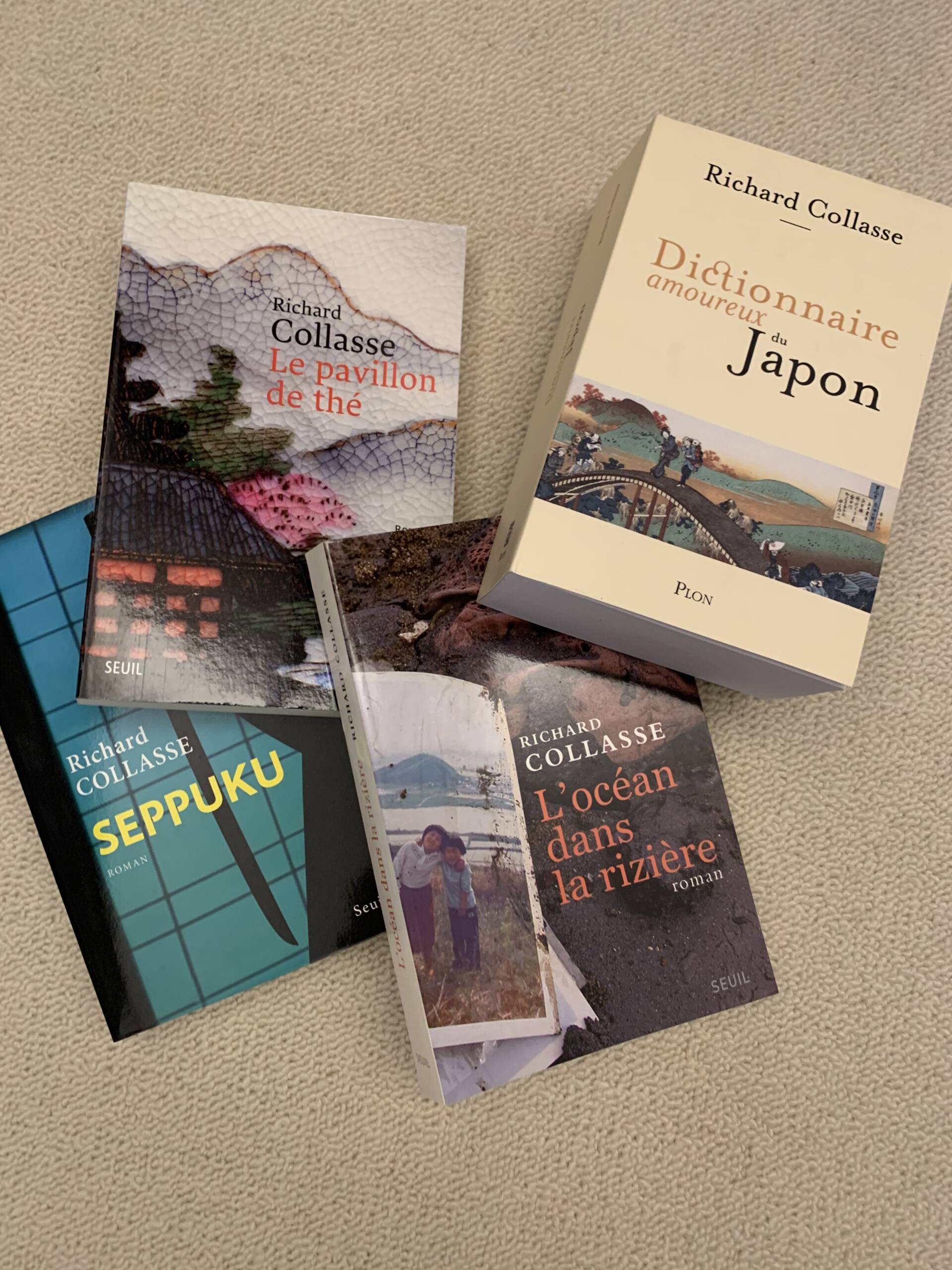

Since first visiting Japan in 1971, Richard Collasse has become deeply involved in its culture, and has published novels in Japan as well as in his native France

DS: It’s so fascinating. Luxury is, of course, bigger now than it was in the 80s. But in what other ways is it different?

RC: It’s an industry that’s concentrated in the hands of very few people, which wasn’t the case in the 80s. LVMH was not that big, Kering didn’t exist and Cartier was like a different company to today. Now all these companies are becoming concentrated, and Chanel and Hermès are the only two remaining in the hands of the [original] owners. China has come to be a rich but, in my opinion, also a fragile business.

Japan, Italy and France retain in common a love for craftsmanship and a passion for sharing it with the next generation. Look at what happened with the reopening of the Notre-Dame in Paris: this should be an eye-opener for young people. The craftsman puts his soul into the product. Far beyond making things well, they have a humility in front of what they are making. That love for the part of the soul they put into the product is unique to these countries.

JS: I think Richard is right. In general, the Chinese value doing things quickly and changing them afterwards, the Japanese want things to be made perfectly. We focus on strategy; they focus on action. It’s often hard to look at each other because we don’t see their vision; just this constant changing.

What advice would you give to young people to find things they can focus on and get passionate about? I find today, a lot of people are on the surface of things, because there is so much coming at us all the time.

After retiring from his nearly 40-year career at Chanel Japan in December 2023, Collasse spent a three-month break as a “temporary monk” at the Za Zen Shinju-An Buddhist hermitage in Kyoto

RC: I think being a visionary is the capacity to create the future – create it, not manage it. You will not have a vision if you are not creative, and this is exactly why I tell kids: try to develop the right side of your brain. What you learn at university is good but it’s not what will make you different, using the right side of the brain will. For many years people were saying they don’t need creatives in business; at a certain point, they were even considered to be dangerous. I remember someone saying it’s good to have you, Richard, but two of you would kill the company! Today it’s different. I think people have to come out of their comfort zone. I always tell my salespeople: get out of your sales point, go and see a different one, and then come back and look at it as a customer. This is part of creativity: to get out of yourself. Nobody teaches young people how to do this, or its benefit, including the pleasure in creating something that works.

Read more: Simon de Pury interviews Olafur Eliasson

DS: One last question: you mentioned, Richard, that Hermès and Chanel are the only big companies controlled by their owning families. How much of a difference does that make if you look at the brands?

RC: I knew we had a certain agility – everything came from my boss’s pocket, essentially. Chanel always does what it thinks is correct, not what other brands are doing. That will stay as long as the company stays in the hands of the owners. At the same time, they structure it differently from the past: they decided that a $20bn dollar company cannot be run weight-first, they also want management. But their vision is not changing, and they try to make sure that people understand this and execute it as it is. This made it easy to follow the vision: it has remained the same for the past 50 years, so you don’t have to worry about what is going on around you. That’s of course more complicated to do now when you’re an $80bn dollar company. But the vision is not changing, and that is very reassuring.

Series coordinator: Charlotte Martin. Online editor: Cleo Scott. Chief sub-editor: Marion Jones.

chanel.com/jp

luxurynsight.com

2. Can you tell us your favourite story about one of the bags you’ve sourced?

2. Can you tell us your favourite story about one of the bags you’ve sourced?

LUX: You also dress a lot of high-profile athletes and sportsmen. Do you take a different approach to designing their clothes?

LUX: You also dress a lot of high-profile athletes and sportsmen. Do you take a different approach to designing their clothes?

Recent Comments