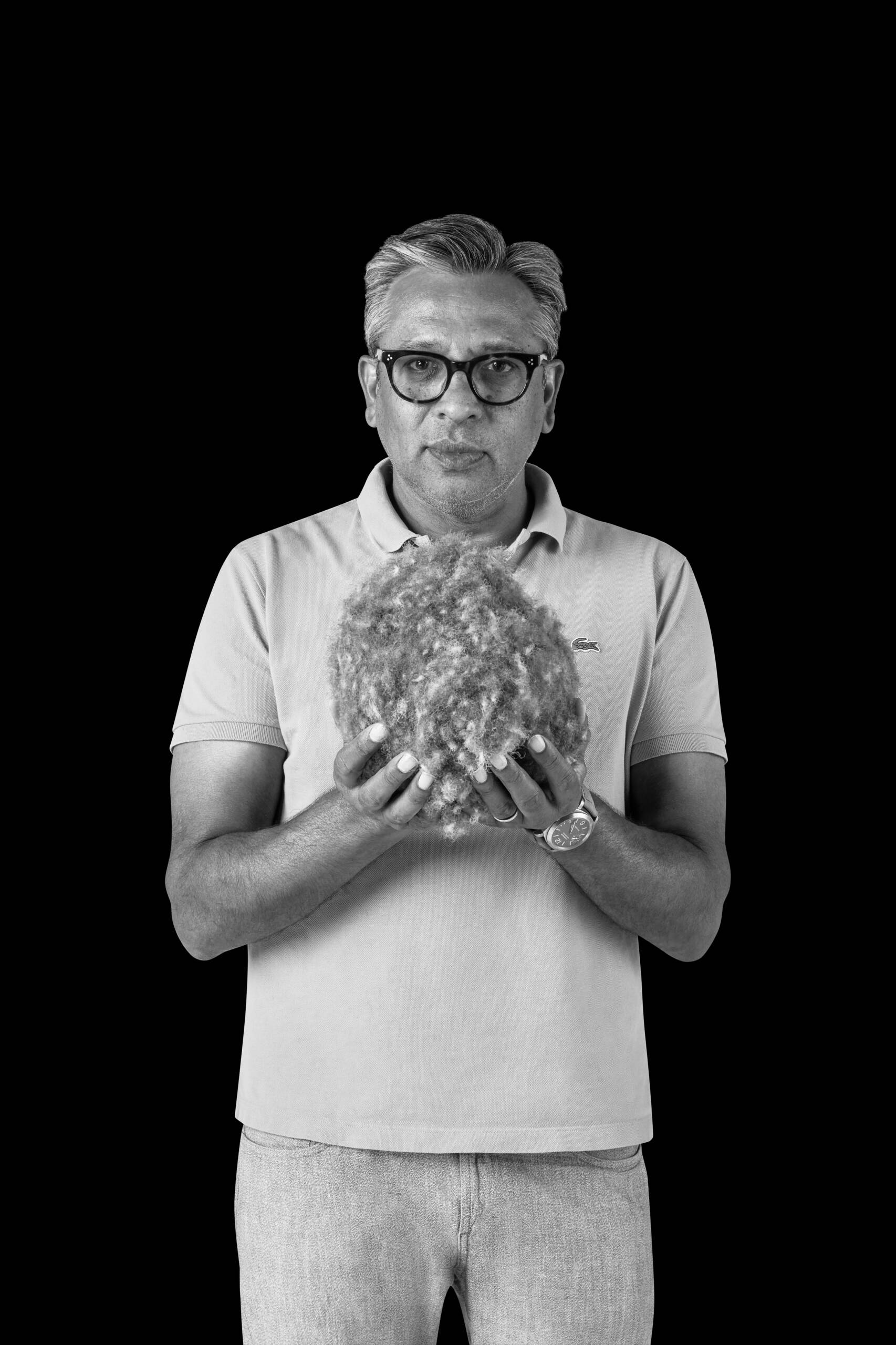

Bas van Kranen, Executive Chef of Restaurant Flore at Hotel De L’Europe in Amsterdam

Dutch chef Bas van Kranen has redefined fine dining throughout his career at restaurants Bord’Eau and Flore, introducing plant-forward menus with a focus on sustainability – and earning two Michelin stars along the way. In a conversation with LUX, he tells us about his beginnings as a chef, his inspirations in Dutch agriculture, and the future of micro-seasonality in fine dining

LUX: You started your career quite young at 14, after a dinner at a Two-Michelin-Star restaurant. What was the name of the restaurant and the food that night, and how did it spark your passion?

Bas van Kranen: I actually didn’t eat there. I started working behind the dishwasher. The restaurant was Da Vinci in Maasbracht, just two streets away from where I grew up. At 14, I knocked on the door and asked Margot Reuten if I could get a job in the dish pit, because I wanted to become a chef.

The outside of Restaurant Flore, where sustainability meets fine dining in a serene, Michelin-starred setting.

From that moment, I was completely absorbed by the rhythm, the ambition, the quality of the food, and the service. It was like entering a different world. I had been fascinated by food since I was six. There are so many photos of me smiling with something edible in my hands. Working at Da Vinci set the tone for everything that came after. It showed me what was possible when passion meets discipline, and it gave my ambition a clear shape: this is what I wanted to do with my life.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

LUX: And now you’re known as one of the youngest chefs in the Netherlands. What would 14-year-old-you say if he saw where you are now?

BVK: He would probably be amazed. But I think he’d also recognise the drive. I consider myself lucky to have a mindset that doesn’t settle. The moment a goal is reached, I’m already looking forward to the next. What matters to me today is the idea that anything you choose to do, you should do it as well as you possibly can. Whether it’s a simple salad, a sandwich, or a bunch of flowers on a table. If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well.

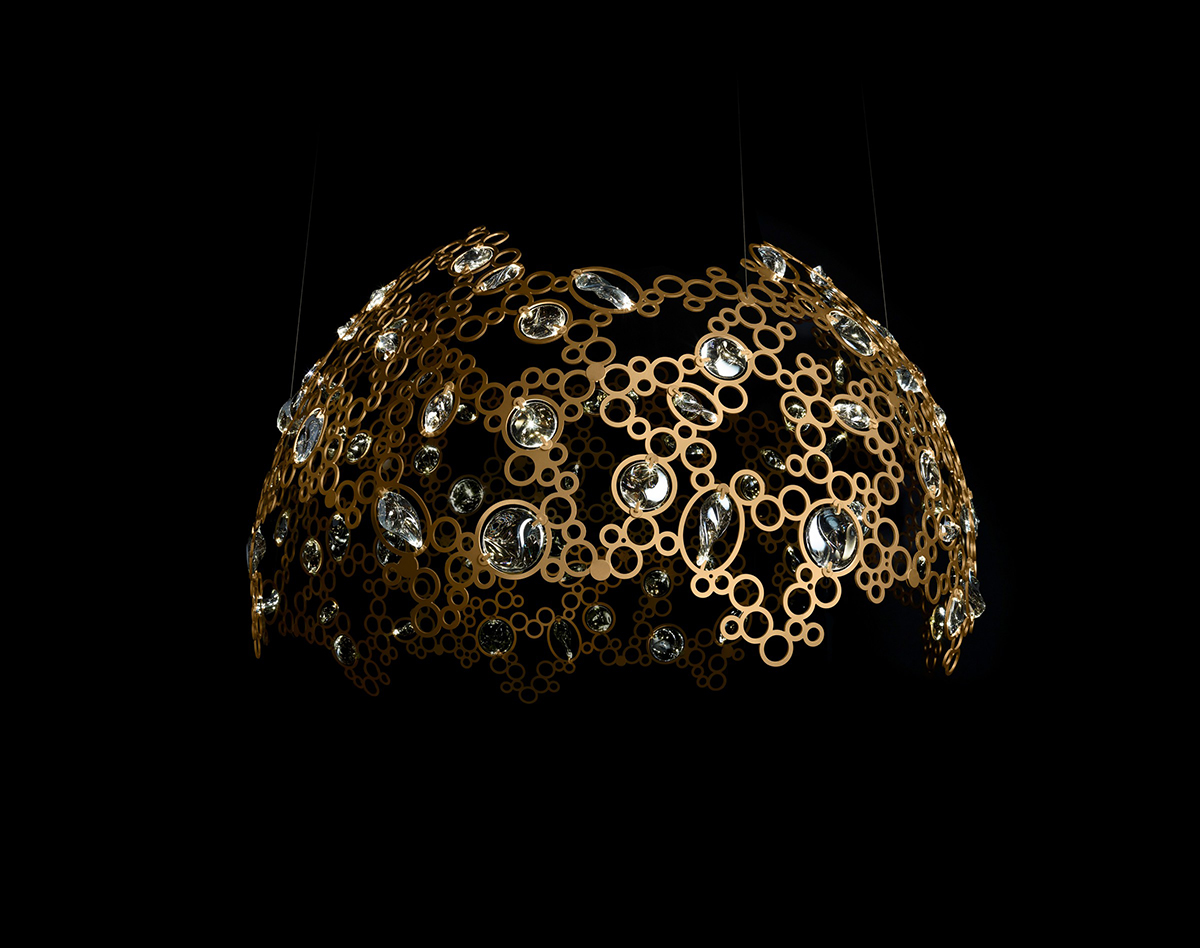

The beautifully curated interior of Flore

LUX: Flore is reopening and many are excited – but what inspired the name? Can you define the meaning behind ‘Flore’?

BVK: The name ‘Flore’, derived from flora, meaning ‘blossoming’, encapsulates the essence of our culinary philosophy. It represents the plant kingdom and the unfolding of flavours in each dish. The name speaks directly to our vegetable-forward approach and our connection to the natural rhythms of Dutch agriculture. Just like plants flourish under the right conditions, we believe flavours should be allowed to express themselves at their natural peak.

Read more: Mont Cervin Palace and Beausite, Zermatt review

LUX: With the reopening, the interior and design have also been renovated. What elements and inspirations shaped the new space?

‘It’s all about harmony between the food, the space, and the story we’re telling’ – Bas van Kranen

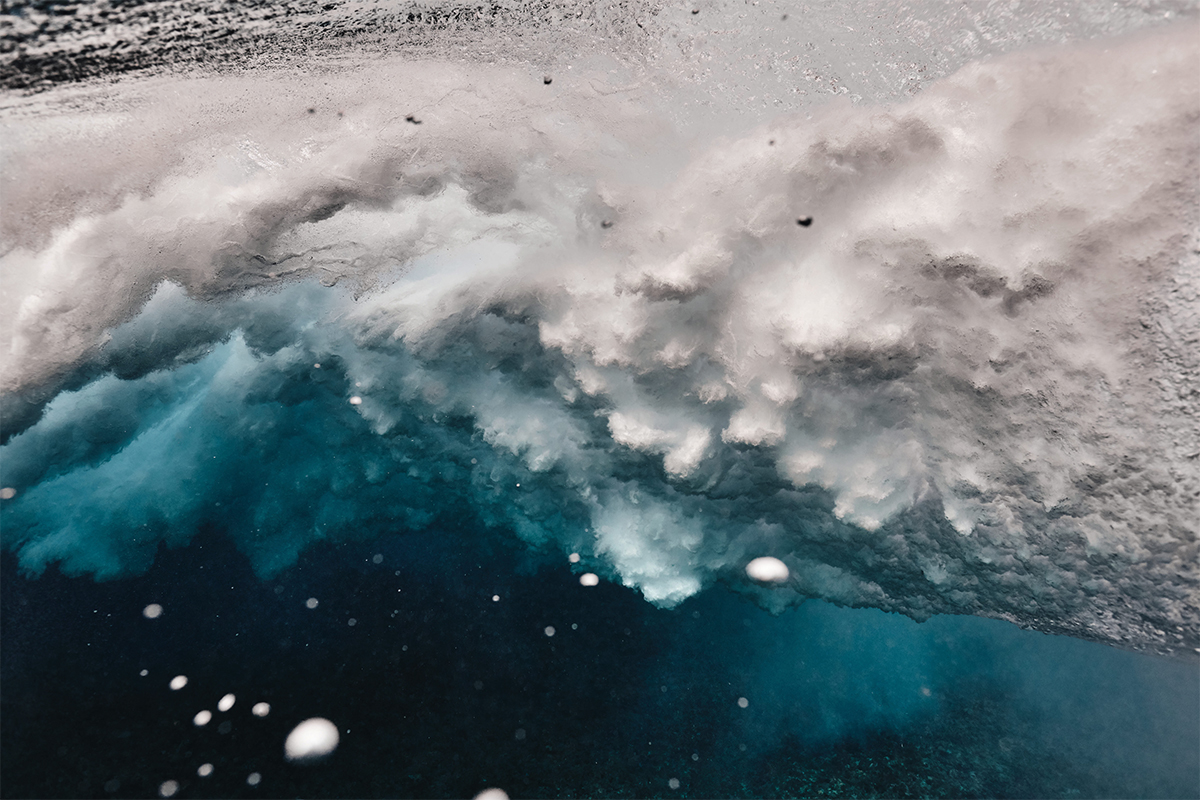

BVK: We wanted the design to reflect the same values as our food: rooted, natural, and intentional. Together with Reiters-Wings Studio, we used carbon-negative materials inspired by traditional building methods, for example, lime and hemp plastered walls. The ceiling undulates like the Amstel River, bringing a sense of movement and locality. The furniture is reclaimed wood, and we designed the ‘Flore Chair’ in collaboration with Tim Reiters to complement our vision. It’s all about harmony between the food, the space, and the story we’re telling.

LUX: The phrase ‘conscious fine dining’ – how would you define that, and how does it live at Flore?

BVK: Conscious fine dining means making the best possible decisions at every step, not just in cooking, but in sourcing, design, and service. At Flore, we work with hyperlocal ingredients, maintain a deep fermentation program to minimise waste, and collaborate closely with biodynamic growers across the Netherlands. We aim to prove that true luxury isn’t about imported rarity but about care, quality and proximity. Conscious fine dining shifts the focus from status to substance, from exclusivity to integrity.

Culinary innovation is at the heart of Flore, seen in this transformed risotto dish

LUX: Your travels have influenced your cuisine – how do you translate those inspirations into your dishes?

BVK: Travel for me is about learning techniques and principles, not copying flavours. Spending time with different cultures around the globe has taught me a huge amount about balance, fermentation, restraint and seasonality. Japanese cooking in particular has influenced how we draw out deep flavour with minimal intervention. We don’t recreate dishes from other cultures. Instead, we use those techniques to express Dutch ingredients in a new and more meaningful way.

Read more: The morning after the night before at St Moritz’s Dracula Club with Heinz E. Hunkeler

LUX: What country has been your favourite to visit, and what dish did it inspire?

BVK: Japan has made the deepest impression. The culture is rooted in respect, technique, and nature. It’s incredibly refined. Right now I’m studying how to age and refine seaweeds, the way Japanese chefs have been working with kombu for hundreds of years. It’s like a new language of flavour. That’s the beauty of it. It never ends.

No dish is repeated at Flore; each dish is made using local and seasonal produce

LUX: Flore was named ‘Vegetable Restaurant of the Year’ in 2024 and holds two Michelin stars and a Green Star. What did those awards mean to you, and are there any other recognitions you aspire to?

BVK: Receiving two Michelin stars and a Green Star within eight months of reopening was incredibly affirming. The ‘Vegetable Restaurant of the Year’ recognition meant a lot, not just for us, but for the shift it represents. It shows that a plant-led menu can lead the conversation in fine dining. We’re not chasing more titles. What we want is to help redefine what excellence means in our field, to set a new standard that includes responsibility alongside creativity.

LUX: Why did you decide that no dish would be repeated, and that the menu would evolve constantly throughout the season?

‘The space, the interaction, the materials, the sound – everything is designed to support what’s happening on the plate’ – Bas van Kranen

BVK: It’s a direct response to our commitment to Dutch micro-seasonality. We work closely with nature and producers, adjusting our menu every week based on shifts in weather, soil and harvest. This keeps us creatively alive and allows us to present each ingredient at its absolute peak. It also invites guests into a specific moment, one that can’t be repeated. That kind of authenticity is powerful.

LUX: What changes do you see in the dining habits of your guests?

Read more: Six of the best hotels in Scotland reviewed

BVK: There’s a noticeable shift towards conscious dining. Guests are more curious, more engaged. They want to know where things come from, how they’re made, and what they represent. There’s also more openness toward plant-based options and non-alcoholic pairings. We’re seeing a move away from the old markers of luxury, toward something more thoughtful and personal. That’s very encouraging.

LUX: Is there a generational difference in what people like to eat?

Some seasonal produce used to create the ever-changing menu at Flore

BVK: Younger guests are often more fluent in sustainability. They’re excited by fermentation, by unusual vegetables, by zero-waste thinking. But across generations, we see a growing interest in real food stories and a willingness to step away from what’s expected. Older guests sometimes have deeper emotional connections to traditional ingredients, which leads to interesting conversations. What unites everyone is a deeper awareness of the impact of food.

Read more: Inside Aston Martin’s Valhalla and Vantage

LUX: How important is the overall experience beyond what’s on the plate?

BVK: They’re inseparable. The space, the interaction, the materials, the sound – everything is designed to support what’s happening on the plate. We want guests to feel a shift when they walk through the door, a kind of transition into a more grounded, present moment. Conscious fine dining is about mindfulness as much as taste. When all elements are in alignment, the experience becomes something you carry with you.

The entrance to Flore: ‘We want guests to feel a shift when they walk through the door, a kind of transition into a more grounded, present moment’ – Bas van Kranen

LUX: Who are your culinary heroes?

BVK: Dan Barber, for his work on agriculture and flavour. René Redzepi, for changing the way we think about fine dining. Yoshihiro Narisawa, for translating nature so elegantly onto the plate. And Jonnie Boer, who has been putting Dutch ingredients like magnolia, wild duck, crayfish and pikeperch on the map for over 25 years. I have great respect for that.

LUX: If you could be transported anywhere in the world to eat and drink anything, what would it be, and with whom?

BVK: I’d go to one of the remote Japanese islands with my partner Roos and our close friends. Somewhere in the forest, overlooking the sea. We’d grill freshly caught fish, open a pot of aged miso, and make a salad from Japanese seasonal greens. And we’d drink a bottle of Nichi Nichi sake – one of the best I’ve ever tasted. That’s the dream. Good food, natural surroundings, and people you love around you.

Recent Comments