Idris Khan in his studio with new works incorporating musical scores. Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Idris Khan is one of the world’s hottest abstract artists, drawing on his Muslim heritage to create works that gain a different meaning every time you look at them. Darius Sanai meets him in his London studio to discuss colour, the Koran and his suburban childhood, while Maryam Eisler photographs him

I first met Idris Khan on a plane. We were flying back from a private view of an exhibition in Baku, where both he and his wife Annie Morris have had their works shown in the Zaha Hadid-designed Heydar Aliyev Center.

Idris was scrawling through some photographs he had taken on his iPad. They showed aspects of Hadid’s then new design in an abstract, mystical, almost humorous way. I said I wanted to publish them in one of the magazines I edited for Condé Nast; after a little persuasion, he agreed.

At that stage, I had no idea that Idris, one of Britain’s most prominent painters and sculptors, had originally trained in fine art photography. It explained the richness of the images I saw on his iPad that he had taken just for his personal pleasure.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

It is, in fact, hard to classify Idris, hard to pin him down. As he points out in the interview below, even his ethnicity is not quite what it seems: he possesses a completely Islamic name, but is half Welsh and was born and educated in the UK. Tall, slim and fair-skinned, he could pass as any Englishman in the lanky Jarvis Cocker mould; but he was actually brought up as a devout Muslim by his father, a surgeon from Pakistan who had settled in Birmingham.

His art is also deceptive. He has created his own, distinctive and trademark shade of blue, known informally as ‘Idris Khan blue’, through blending ultramarine and Prussian blue; yet he is a sculptor and maker of 3D objects as much as a painter.

Every time I meet him, he is gentle, thoughtful, disarmingly self-deprecating, and not in a staged way. But there is an intensity and steeliness there, and originality of thought amidst the lightness of touch, that has allowed him to become the celebrated artist he is.

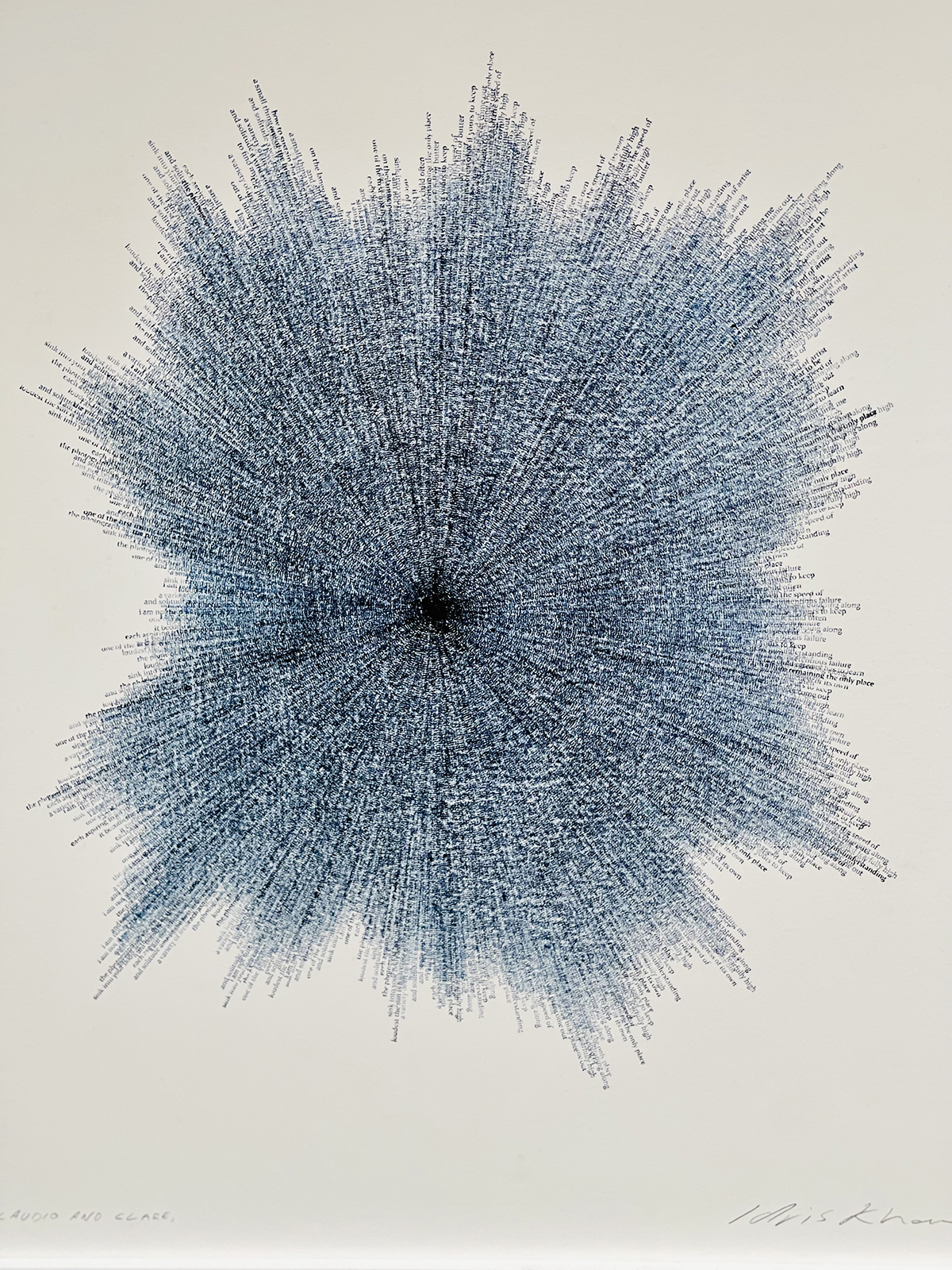

One of the artist’s works with stamped texts

We meet at his studio in an artistic area in east London. It is a striking, warehouse-type building on a single floor; his wife, the acclaimed sculptor Annie Morris, occupies a near identical studio next door. Walking into Idris’s studio, you find yourself in front of a long, wide art table with paints and objects neatly lined up. There is a multitude of materials, but it is the tidiest studio I have seen.

At the back, behind the glass partition, is his office; behind his desk are stamps of lettering he creates for some of his works. They are artworks in themselves. A passageway off to the left leads to an open-plan kitchen area which opens out into Morris’s studio. She is there, working on a spectacularly coloured array of sculptures and stained glass; she chats to us for a while before returning to her own works.

Khan has been commissioned to be the Lounge Artist for Deutsche Bank at Frieze London 2021, where the artist will be creating an immersive blue environment. Meanwhile, I look on while Maryam Eisler photographs him in a variety of locations in the studio for our cover, and then he and I settle down on suitably socially distanced chairs to chat.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

LUX: Was there anything in your background to suggest you would become an artist?

Idris Khan: I had a very normal suburban upbringing: my father was a surgeon and mother was a nurse and I was a really sporty kid. It was probably through education that I sort of fell upon becoming an artist.

Read more: The eco-art organisation making a stand at Frieze London

LUX: So, when you were single digits, were you doing artistic things?

Idris Khan: No. I can remember loving to draw, but the creativity came late, probably when I was around 17 or 18. I went to do a foundation year and it was photography that gave me the keys or the tools to go on and express myself in an artistic way.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

LUX: There was no plan to become an artist?

Idris Khan: No, I wanted to be an athlete. It was strange. I loved running – that was my top sport. But it just didn’t work out and it was just like, “What’s the next thing, the next best thing you’re good at?” It’s funny, isn’t it? That weird pressure when early on you want an artistic career, especially when two professional people – my parents – were saying, “Well, you know, graphic design is what you need to go into.” And I was thinking, “Hmm, I don’t want to be a graphic designer… my portfolio is full of photographs and beautiful things.” And from no understanding of that kind of career, I had to fight for it. I went to Derby University to study for my photography BA and had great teachers there and that helped me. They paved the way for me to come down to London to do my master’s at the Royal College of Art.

LUX: Did you always expect to be an abstract, conceptual photographer?

Idris Khan: Very much so. I never really saw myself as someone who was going to be a landscape photographer or go out into the world and take those kinds of pictures. I was already a studio-based photographer and for some reason I always liked photographing very still things. It’s interesting – when you’re a student, you’re sort of looking for things that you want to pursue in some way and so, I found myself going back into empty sports interiors. It’s kind of weird, the access a camera gives you to go into these places. So, I would photograph the walls of squash courts. I loved the marks that were made in the squash court wall. Somehow, when you frame those marks they start to look like paintings. They no longer look like a squash-court wall; the marks in the wall and the floor just started to have this energy, and there’s a certain element of stillness. It’s amazing that a photographer can get access to empty spaces like that. I’d say, “Oh, can I come and sit in your squash court for half an hour?” Normally they’d say no, but a camera gives you this licence.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

LUX: And how would you describe yourself? An abstract artist? Or is that irrelevant?

Idris Khan: It is relevant. I think I always try and push that level of abstraction, whatever medium I’m working with. So, if I’m working with a photograph, I like the deception that you don’t know whether it’s a photograph or not, it just looks like my hand or marks made on a piece of photographic paper. I think it was about three or four years outside of college that I met Annie and she was the first person to say, “Well, why don’t you make a sculpture?” I did a bit of film and things like that, but she said, “You know what, there’s a great idea. You deal with layering photographs. Why can’t you deal with that same idea, but in different materials?” So, I made my first sculpture for which I sandblasted musical notes onto steel and used that same process of repetition and layering and time and the eradication of time, and then that sort of led itself into what I’m doing now with the big blue paintings and language eradicating language. Same idea, just pushed into different mediums.

Read more: Sophie Neuendorf on the Legacy of Valmont’s Didier Guillon

LUX: Musical notes and stamps of verses – why are they of interest, particularly?

Idris Khan: I think Islam probably gave me the sort of trigger to deal with repetition and language and the eradication of language. And the reason was that my father wanted us to become Muslims; we were praying five times a day, mosque every Friday afternoon… that’s what he wanted for us. And of course, it became an act of rebellion: first my brother, then my middle brother, then me. I said, “Well, now we’re not going to do this anymore.” But I can’t help that, somehow, that part of my life is inherent in what I do. So, talking of repetition for example, I find Islam very repetitive – returning to the prayer mat every day, repeating the same verses all the time. I remember very clearly my father saying, “Repeat after me, repeat, repeat after me…” – and that’s the way I was processing language. I didn’t know what I was saying. I think what I do is a reflection of that, to be honest. Looking back to my twenties, the work I was making and the way I was using language, I was kind of confused with the culture when I was growing up. Being the only white kid in the mosque, it was kind of a role reversal in terms of race. I was the white boy everyone was looking at and I felt uncomfortable. Am I using that way of linking something to my heritage or trying to eradicate it? That’s the kind of thread I could try and bring together.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

LUX: And what’s your relationship with your heritage now?

Idris Khan: I don’t know. I really like the fact that I have it to tap into occasionally. I don’t think there’s many kids from that sort of background who actually do become artists. And I’d love to give back to that culture a little bit. I’m doing a proposal at the moment [for a spectacular public sculpture in Saudi Arabia] and I don’t think you could go there with a British name and delve into the Koran. But my name gives me access to be able to do that; there is that little bit of faith, perhaps, somewhere deep rooted, that I can engage with and have an idea and a concept that I can push.

LUX: So you feel that your name is more Islamic than you?

Idris Khan: Yeah, definitely.

LUX: Is that a drawback or is it just a thing?

Idris Khan: I think it’s just a thing. It’s funny when people see me and they haven’t seen a photograph of me or anything like that, they’re always very surprised by what I look like. Maybe I should just look a bit more exotic. I’m not sure, but I definitely think that’s the case.

LUX: Do you feel obliged to make art that your gallery can sell?

Idris Khan: It changes. I think when you were young, you obviously want to start working with a gallery straight away. I felt that I was very nurtured by Victoria Miro in London. I was a 24-year-old coming out of college, quite young for an artist to start working with a commercial gallery straight away. And what was in my mind at that time was if I was making something for sale. So, every show from then on adds more pressure to have a successful exhibition, meaning: does the work sell out? And I have found that over the past 15 years or so that the pressure to sell is much higher than it was. Because of the art fairs and the machine that is the art world, there’s a lot more pressure. I suppose that can spill into the artist’s mentality, but I don’t particularly care too much about that sort of thing. I like making bodies of work. Yes, we’ve got to keep the studio going and things like that, but I don’t like to say, “Okay, if I’m not going to have a sell-out show, then I’m a failure.” I don’t feel that pressure. Everybody likes to say, “Oh yeah, I sold out”. It never used to be like that. And so, what does that mean? Does that mean a successful show? I don’t know!

LUX: How do you control the pressure to sell?

Idris Khan: I like putting limits on the number of paintings; for example, six blue paintings at a particular size. And if you can put limitations on yourself, that’s important too, because otherwise you could just keep going. I could probably have made layered music pieces in black and white from 2006 for years, but I said no.

Khan with his stamp works. Photograph by Maryam Eisler

LUX: And what about museum shows?

Idris Khan: They’re different. I see them as giving me greater freedom to show a breadth of work rather than the usual commercial shows. It’s about what happened in those two years – you’re showing the work you’ve done during that time. What I love about what’s happening in Milwaukee in early 2023 [where the first US retrospective of his work will be held at the Milwaukee Art Museum] is that it’s a survey show of 20 years of my work. And it’s such an exciting thing to do, to bring your work together at different moments and look back and see the journey it has taken and how it has changed. You’re hopefully reaching a much bigger audience than comes for commercial gallery shows and a different part of the audience, too. I hope that part of my career develops more.

Read more: Inside Maja Hoffmann’s Provençal Art Hotel

LUX: What else would you still like to do?

Idris Khan: I’m working on a proposal at the moment [for a public artwork in Saudi Arabia], which is rather big. I’ve been thinking about it for three years. If I get that, it’ll be a wonderful thing to do. I just did a nice little piece of public art in London [65,000 Photographs at One Blackfriars in 2019]. There’s a real excitement when you make something like that, so I’d love to do more.

LUX: How often do you and Annie see each other during the day in the studios?

Idris Khan: You know, Annie is so busy it’s like, “Why would you be coming in here?” It’s only when I ask her to come over for an opinion or I go there, and she has an opinion. And it’s just not about art making. Sometimes it’s about selling a work and everything that comes with being an artist.

Annie Morris with Idris Khan in her studio.

LUX: How did you meet?

Idris Khan: In 2007, she was exhibiting at a gallery in west London. I had a mutual friend called Rebecca in New York. In fact, the first time I met Annie, Rebecca said, “You have to meet Annie Morris.” And then she told me that she was coming to London and said, “You’ve got to come to Annie’s exhibition”. I went but I was a bit lazy, thinking, “God, west London, it’s too far…”. But I went and then she had a show in New York in the same month that I was having one and I flew in to see it and, you know, there’s no lie here, we’ve been pretty much together 24 hours a day since then. She moved in after a month. Got engaged after five.

LUX: Are you very similar as people or just matching?

Idris Khan: Is Annie louder? Perhaps! I suppose maybe similar but different energies. What’s great is we both respect each other’s work massively. I mean, now I’m moving more into colour. That’s probably because I can’t get away from all the colour next door. I was very much monotone, you know, with my black and white works, and then there has been this sort of explosion. She will probably get into more monotone, hopefully! There’s unbelievable respect and influence in both directions.

LUX: Annie is Jewish, you were brought up a devout Muslim. Is there relevance in that?

Idris Khan: I think if Annie was a lot more practicing, then maybe. I mean, there’s definitely choices of faith: holidays, things like that. And the kids weirdly see themselves as Jewish, or want to be more Jewish. They want to have a connection to a religion, which is kind of interesting. I don’t know whether that’s because of the schools they’re going to or whatever, but they quite like to say, “My mother is Jewish, so I am too. My father’s Muslim, but because it’s my mother, that’s what we are.” I’ve got absolutely no problem with that. They like to learn about both faiths as well. I think it’s one of those questions which doesn’t necessarily come up, but it could one day. Maybe the show in Israel [at the Alon Segev Gallery, Tel-Aviv, in April 2022] will be kind of an interesting place to look at that. Could I start using the Torah? Can I use Hebrew to make a painting? Could I combine Arabic and Hebrew together in a painting? What would that look like? That show will be a good excuse to be able to do something like that.

Collaborations with Frieze and Deutsche Bank

Idris Khan took over the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounge at Frieze London this October. “I’m making the Lounge into this kind of blue world with blue carpet and blue paintings. You’re going to be walking down the corridor from the fair, with one of my works made into wallpaper which becomes very immersive, into the lounge. I’m also going to be showing a huge array of the stamps that I have made my paintings with over the past 10 years. I’ve made quite a lot of these stamps – probably over a hundred thousand – but it is the first time I’ve actually exhibited them as an installation. What I really love about them is that they become relics of the paintings. I mean, not many artists can say, ‘Well, here are my brushes’. They’re interesting things as they’re still objects in their own right. Even having been along a kind of journey as paintings, they exist as there are these passages of writings in blocks. I’ll be showing shelves and shelves of these.”

He has also created artworks for the first exhibition, also to be launched in October this year, in a new programme of art to be shown at Deutsche Bank’s new offices in the former Time Warner building on Columbus Circle in New York. “I’ve made four large grid paintings using watercolour and sheet music. Each is a set of nine different variations on a colour tone from blues, reds and greys based on colours of the seasons. I like working with a grid of colour – it’s like looking at the colours of the seasons in one instant. And Annie will be showing a large sculpture there as well. We’re looking forward to seeing it all installed. Hopefully it will be a real explosion of colour as you walk into the space.”

Find out more: victoriamiro.com

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue, for which Idris Khan designed our logo.

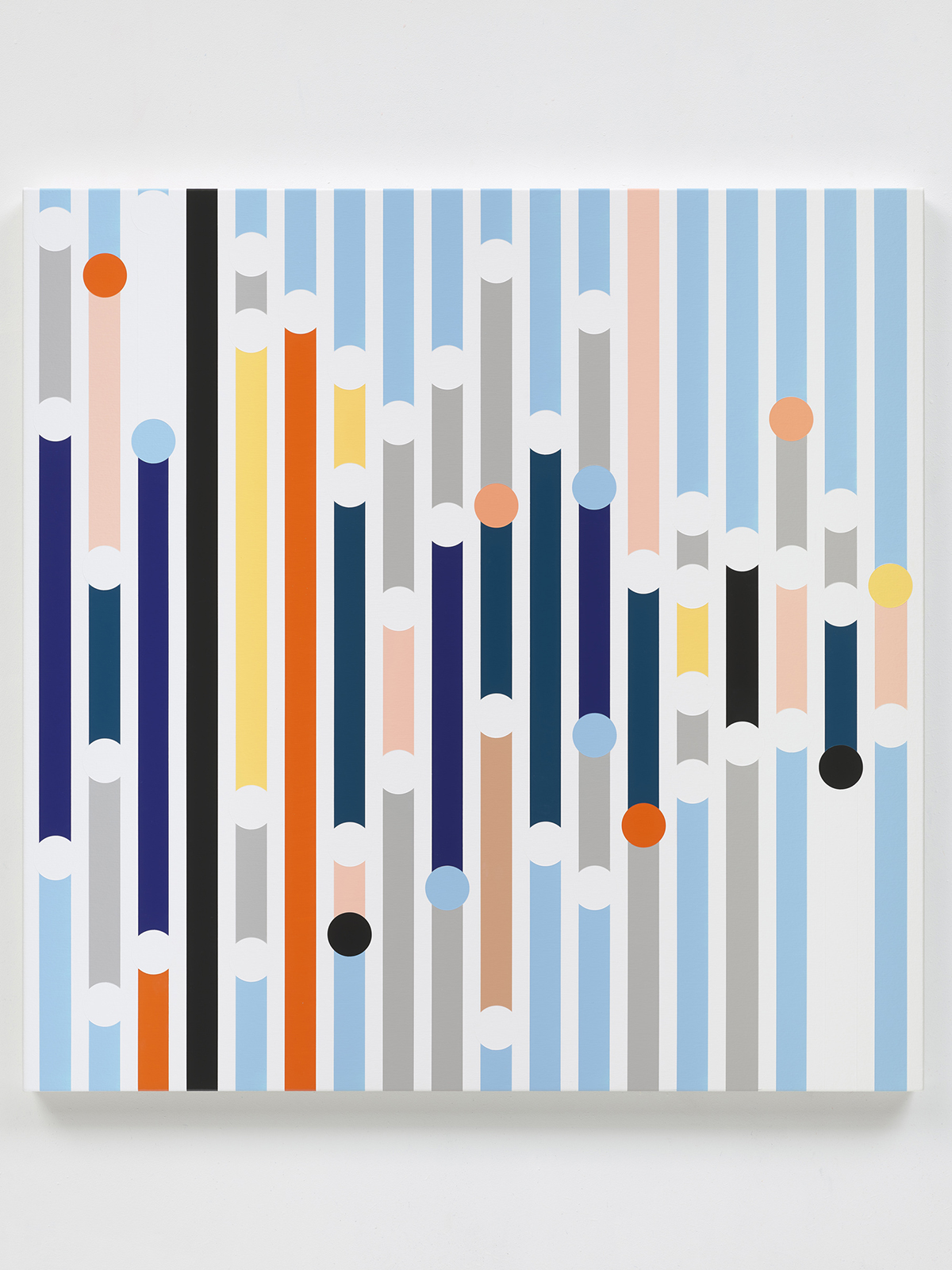

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

Recent Comments