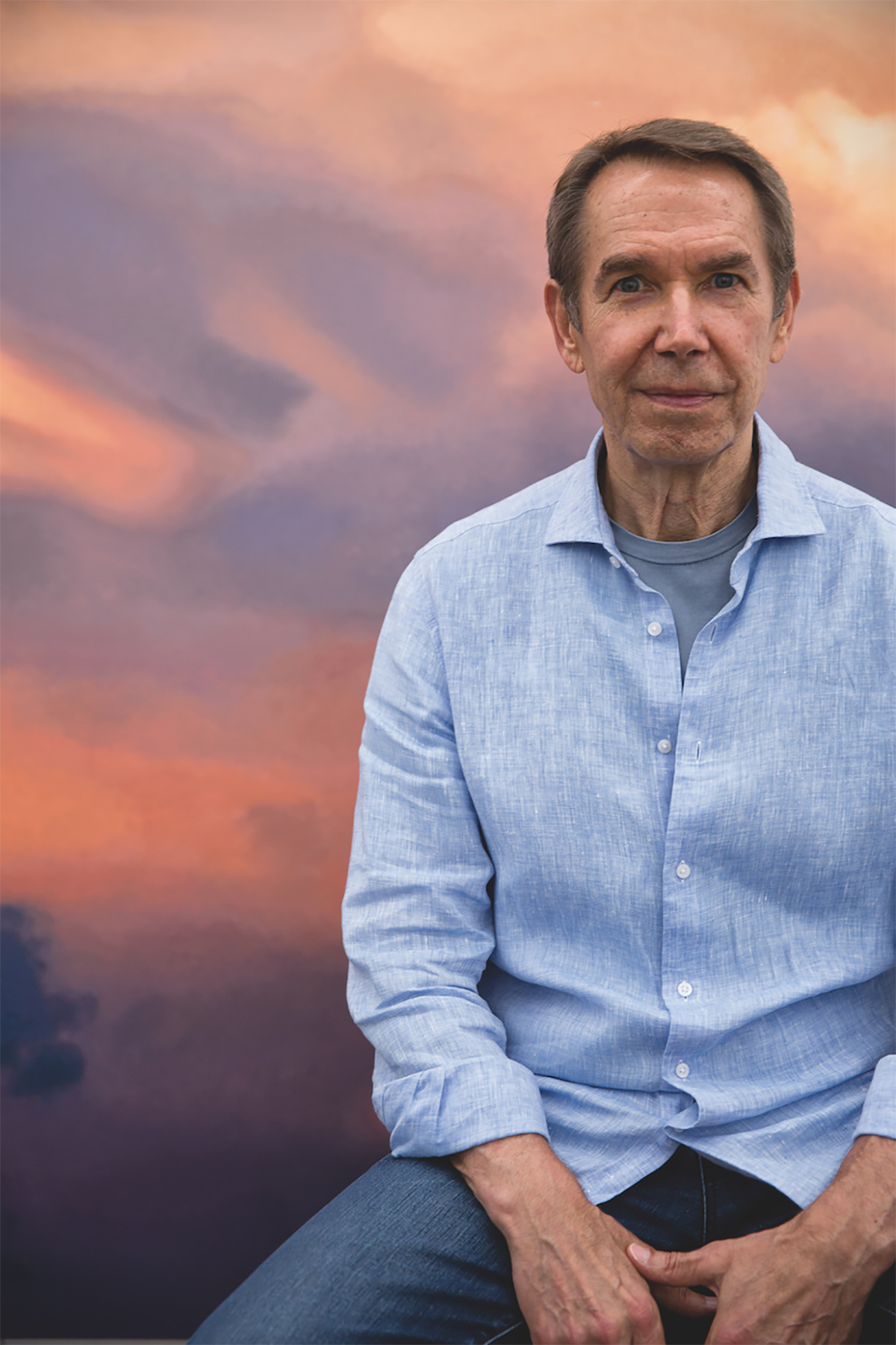

Artist Enoc Perez in his home, photographed by Maryam Eisler

Borne of 1980s New York amongst the backdrop of Warhol, Basquiat, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Puerto Rican artist Enoc Perez has spent his decades-long career exploring questions of identity, heritage, and the urban landscape. LUX Contributing Editor Maryam Eisler talks to him about love, the ‘second phase of life’, and art in the current climate

Maryam Eisler: We’re sitting in your summer studio in East Hampton.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

Enoc Perez: I call it the two-car garage; it’s a studio where my children used to run in as children. This is also where I learned how to make sculptures. I’ve even made little pastoral paintings, something I would not normally do.

ME: Is it a place of experimentation?

EP: It’s my lab. This is a place where I knew nobody would see anything when I first bought it, so I could work privately.

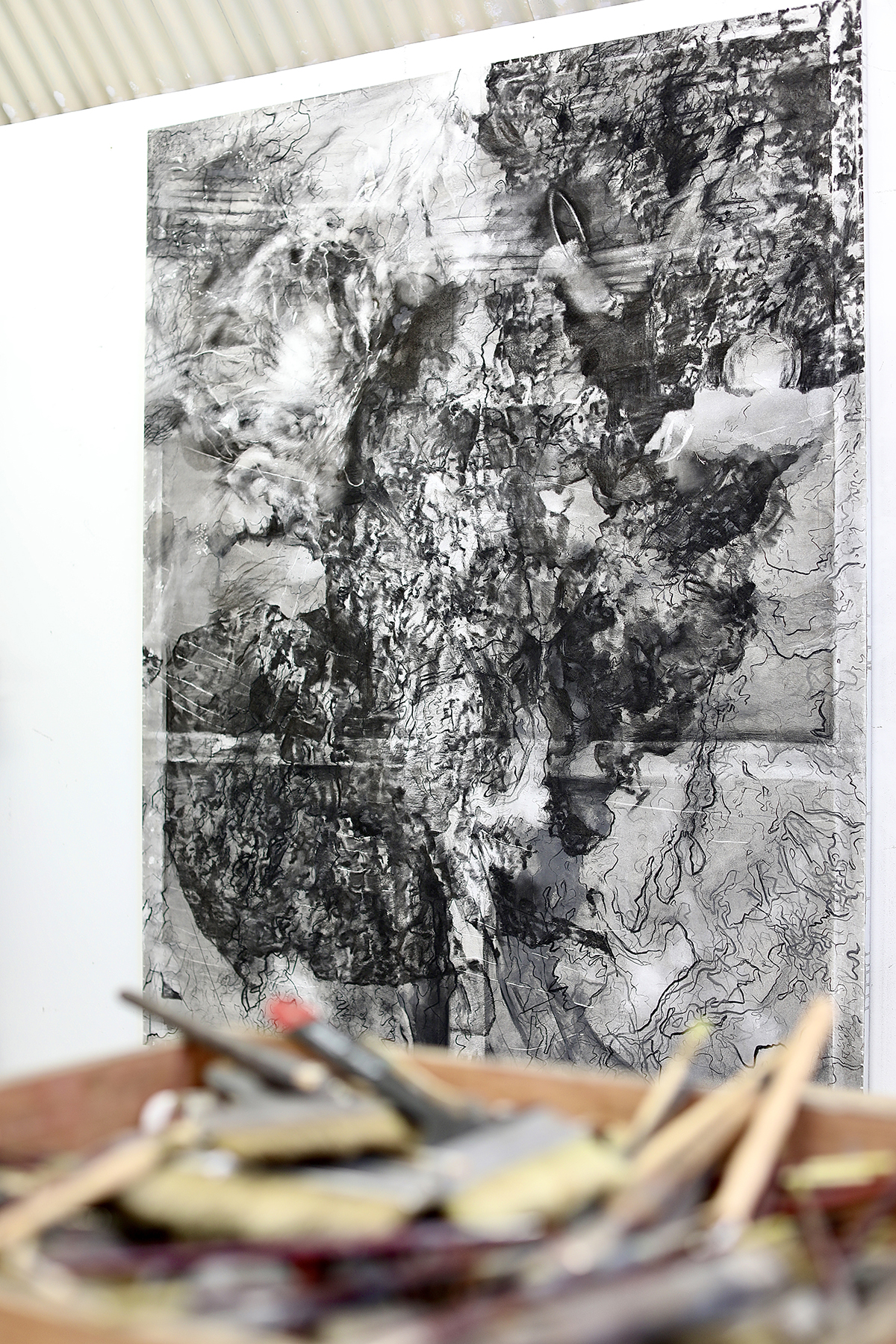

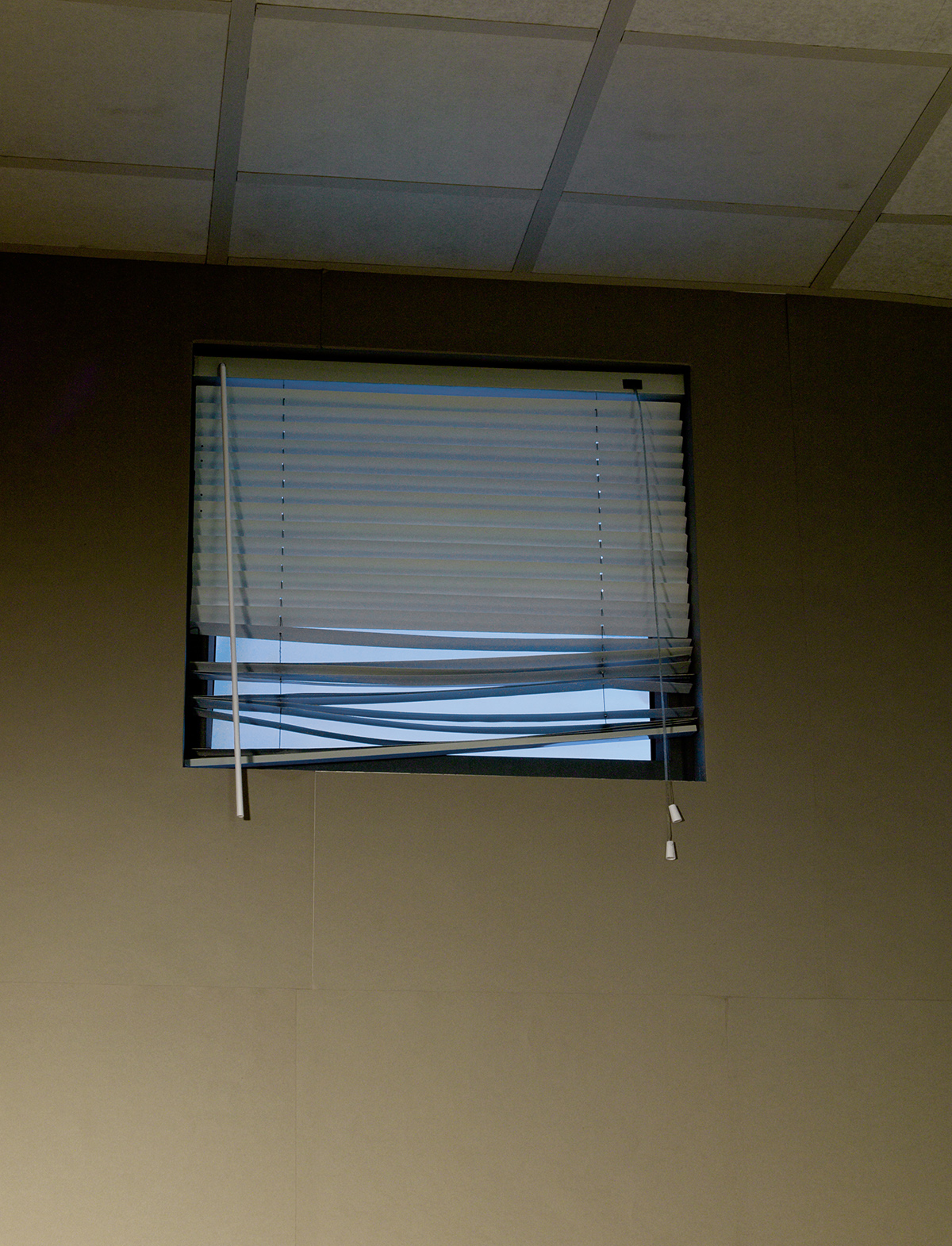

Enoc Perez’s studio, photographed by Maryam Eisler

ME: Your sanctuary.

EP: Sanctuary it was. It’s also about the dreams you dream of. When I was studying art as a young guy, I would see Picasso’s studios in the South of France with Paloma and Paolo, his children, running around. Think of the pictures of Julian Schnabel, with him coming out of the water. I wanted somewhere with a pool, where I could go swim and come back to the studio and work, with my family around, because I personally don’t like to stop working. I feel guilty when I don’t work!

Read more: Luxury travel from the Alps to the Persian Gulf

ME: You told me earlier that this is now the second phase of life; talk to me about your beginnings.

EP: I came here when I was 19 years old from Puerto Rico. I wanted to come here and my dad insisted on that too – if I was going to study art, I had to go to America. He was right. When I graduated at 22, the whole challenge was how to get seen in a city that has so many artists.

It was 1986. Jean-Michel [Basquiat] was still working. I was there. I witnessed it all.

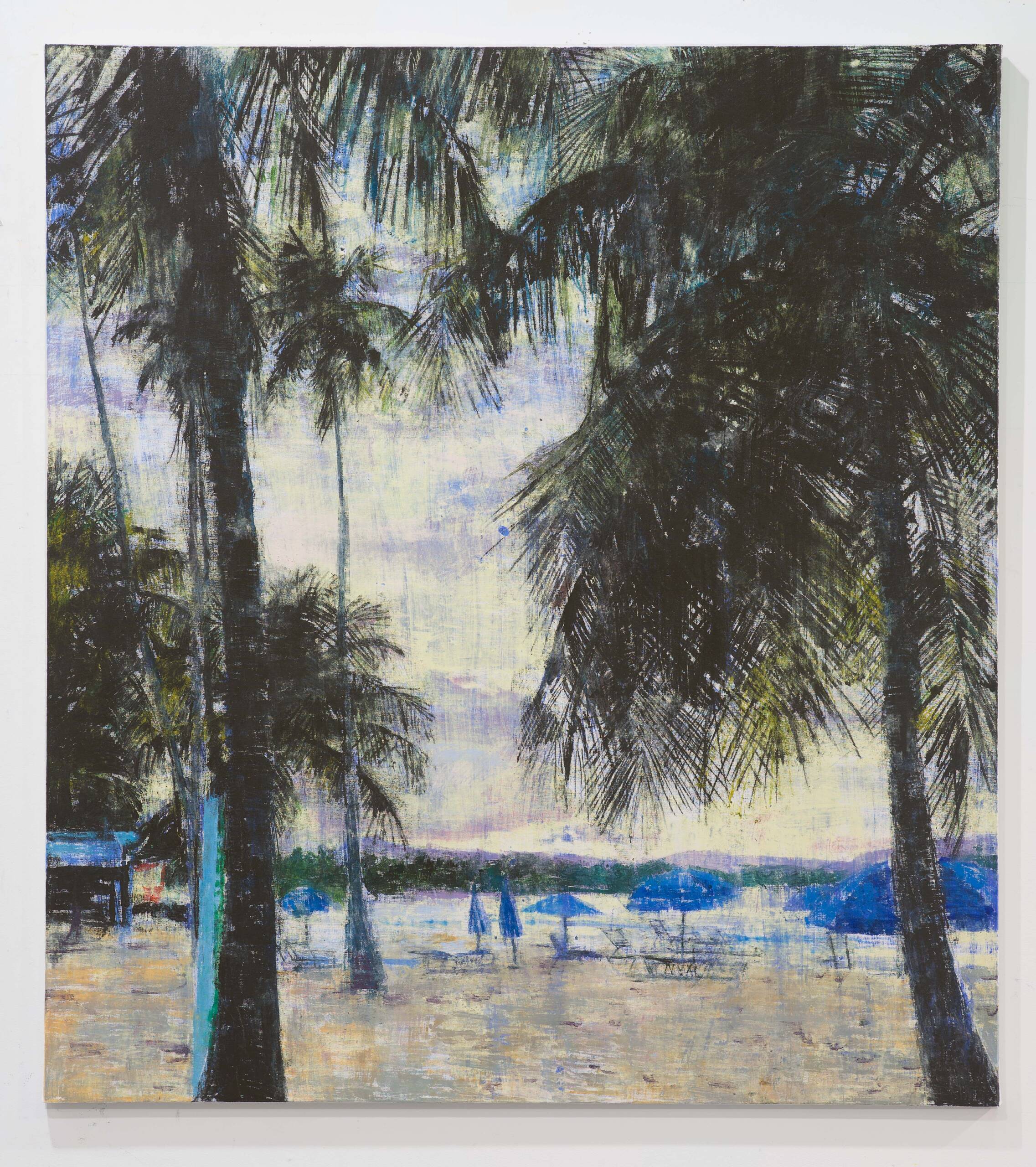

Enoc Perez’s ‘Luquillo Beach, Puerto Rico’, painted in 2025

ME: What was New York like in the 80s?

EP: It was dangerous. It was crazy. You remember The World? You remember all those clubs? It was so exciting. I didn’t even have a style, because I came from suburbia in Puerto Rico, so I pretty much looked like the Sears catalogue!

ME: You were a clean slate, ready to absorb.

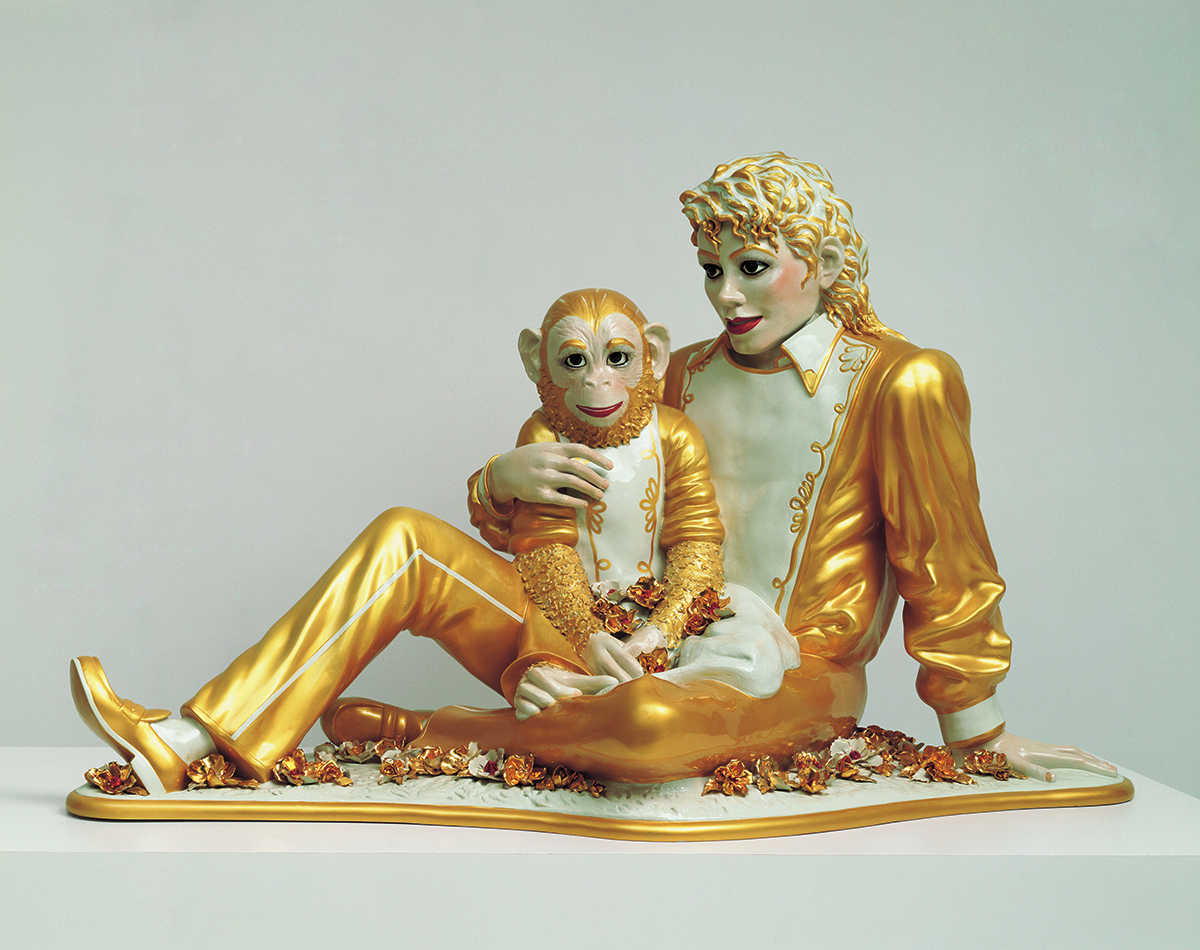

EP: At first, I did my own interpretations of Jean-Michel Basquiat because he was the best. Until I realised that I had to do something that nobody else had attempted or wanted to do, especially as a Puerto Rican. In the early 90s, Felix Gonzalez-Torres started to come to prominence, and he was a game changer – how he saw sculpture and art was mind blowing. I noticed that Felix would be placed into contemporary art auctions, not in Latin American sales. That’s when I decided I didn’t want to be separated.

So, I decided to win the contemporary. Then came questioning of the method. How would I communicate with my audience using a universal language? I looked at Warhol, Rauschenberg, Richard Prince: they all used printmaking in the painting process, especially Warhol and Rauschenberg. That’s when I started doing transfers of drawings.

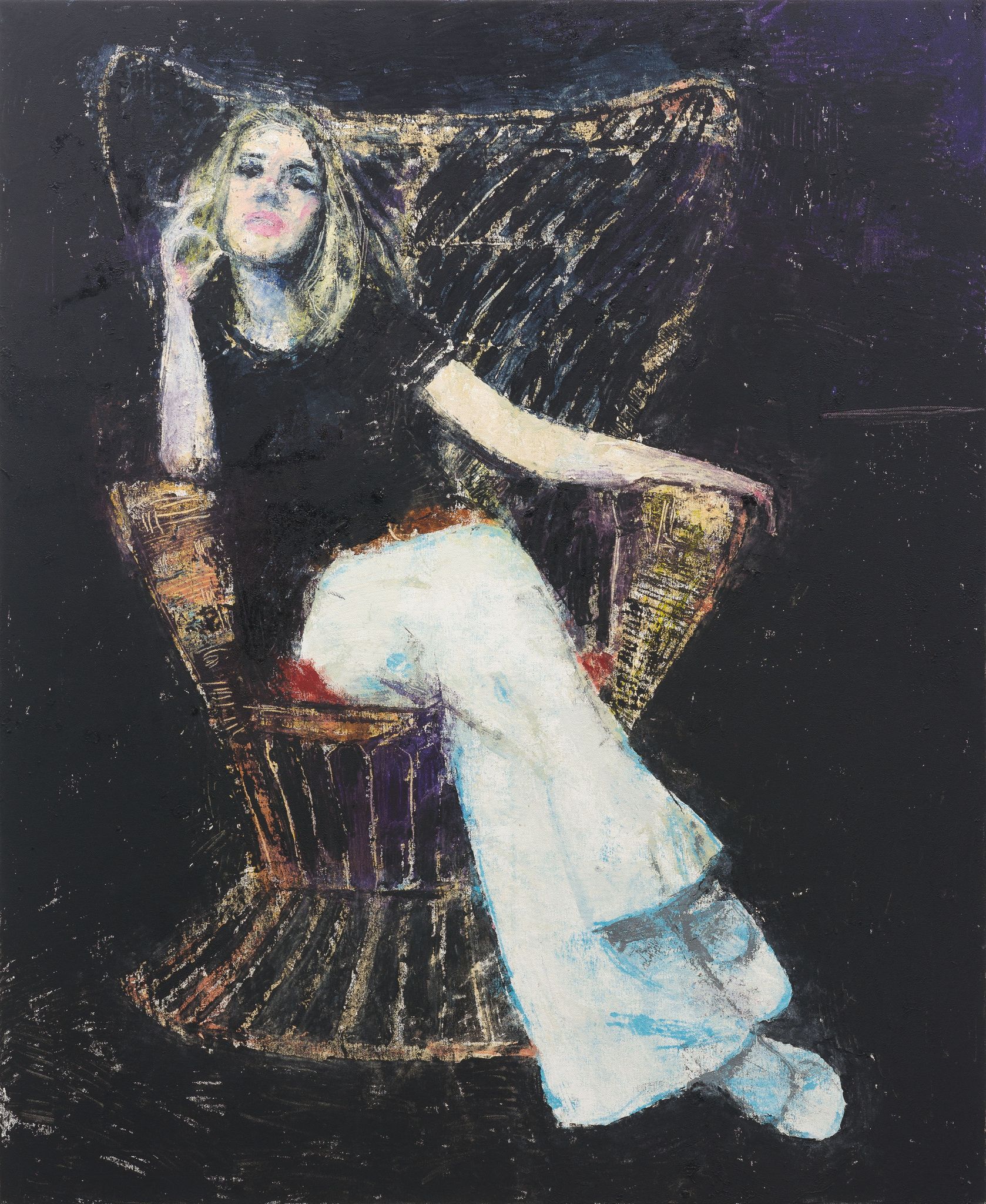

Enoc Perez’s oil on canvas ‘My Mother’s Kitchen’, 2025

It’s like a primitive way of printing. This gave me the relationship I wanted with the New York masters. I wasn’t using any brushes. It was very American. People at the time said they looked like Warhol silkscreens. My sister was working at Ralph Lauren at the time, and I went to pick her up one day for dinner and I noticed they had a colour copier. I opened the machine and it had four colours, the basic colour separation. I thought it would be cool if I used these colours to make my images too. That’s when I started adding layers to my monochromatic canvases.

ME: And that’s how your personal style developed?

Read more: A tribute to Don Bryant

EP: When I started using colours, I knew I had something. I was throwing a house party once, and people were just getting wasted, but they noticed a little painting hanging on the wall. I thought to myself: ‘okay, this is going to work’. I had these non-art and wasted guys actually talking about my art!

I started making paintings of other people’s girlfriends. I was recently divorced. I was angry, so I would take a picture of a couple and cut the guy out. They were paintings about envy, anger and desire. Everything happens because of love. The architecture came up when I first met my now-wife Carole who was married at the time.

Carole’s heels sitting next to the family swimming pool in East Hampton, photographed by Maryam Eisler

ME: Love is everything.

EP: Isn’t it? It’s probably the most basic motivation. But when you’re already in love you have to become more conceptual and talk about intellectual matters.

So, I met Carole. She was married to some other guy, but I wanted to do a show about her, and I decided to do a show in code. This was 2003. I thought to myself, ‘what am I going to do?’. I have a good library of architecture books. There’s a hotel in Puerto Rico called the Normandie. The story of that hotel goes back to the Puerto Rican guy who built it. He had a French wife – a singer. He built a boat for her, but that didn’t work out, so she wasn’t too impressed. Then he built this building based on the famous Normandie liner boat. I said to myself, ‘I am a Puerto Rican and I’m in love with a French woman. This painting will be a portrait of her’. And that was that!

Read more: In conversation with Henry Lumby of Auriens Chelsea

ME: Tony Shafrazi: tell me about him.

EP: Tony? He came in because of the buildings! The works were intellectual and I knew they would spark an interest in someone like him. This was after 2001; we all became painfully aware of the symbols that architecture signalled. Especially after September 11. My architectural symbols were inspired by love. Then, I started thinking about the Caribbean and Latin America, with all their international modernist buildings with beautiful architecture – all symbols of colonisation.

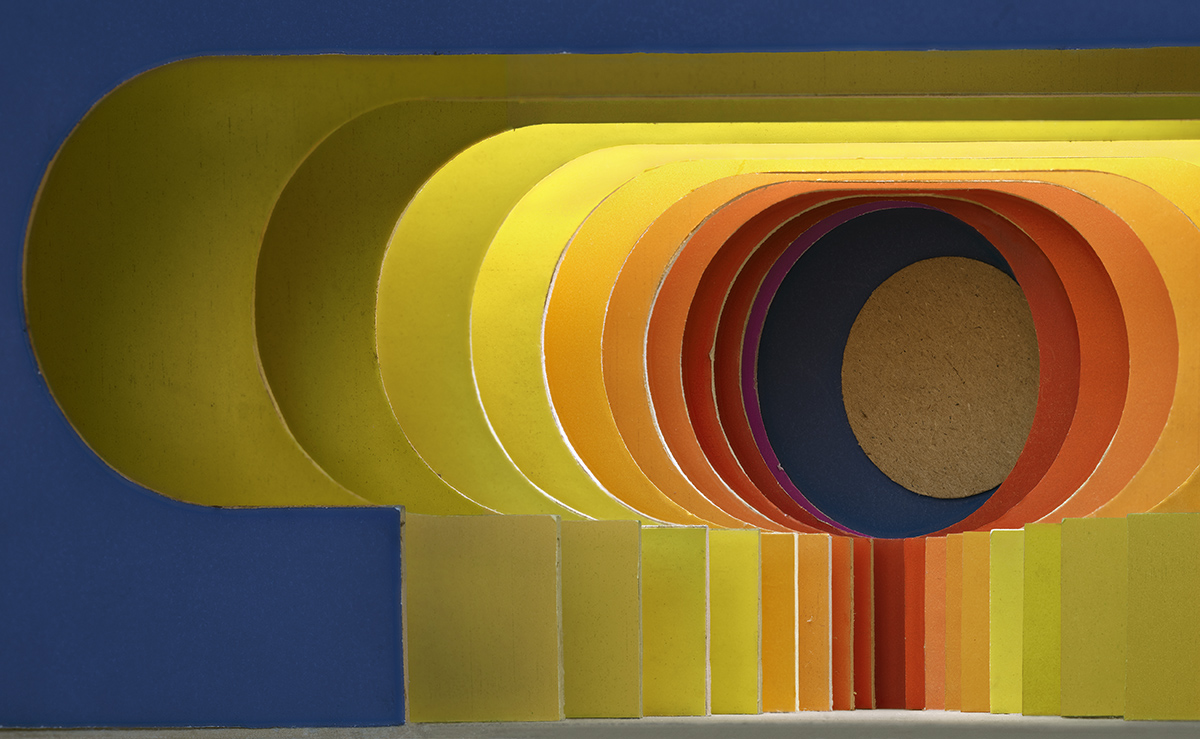

A close-up of Perez’s materials found in his studio, photographed by Maryam Eisler

ME: When did Tony notice your work?

EP: I had a German dealer at the time who took me to Art Basel. He called me and told me ‘Oh, these two guys bought your paintings – all of them!’. He wouldn’t tell me who at first. Anyway, months went by and then he told me, ‘Well, it was Peter Brant and Tony Shafrazi’. At that time, I was starting to join forces with Elizabeth Dee in New York, so she put Tony in contact with me, and the rest is history. Tony even came to our wedding.

ME: Do you regard Shafrazi as your godfather?

EP: He’s a godfather to a lot of artists. But, for me, he was my refinement school. He’s the guy who tells me, ‘No, you cannot do that’, or, ‘Think about it a little more’, or, ‘Challenge me’. He understands art like no one I know. Peter Brant, too. We became friends; Peter commissioned a portrait of Stephanie Seymour. These two men are blessings in my life.

ME: Let’s move to your paintings of beautiful sensual women. You told me that you felt there’s no room for showing these works now? Why not?

EP: I would get killed. I mean, I’m a 56-year-old straight guy. It doesn’t look good and people would criticise me.

‘Ponce Intercontental’, 2023. For Perez, architecture is richly embedded with symbols of love, as well as modernism and colonialism

ME: Do you self-censor?

EP: Well, there’s some degree of self-censoring. But with art, you can store it and bring it out when the time is right. Carlo Mollino has been an inspiration; he found a way to show the female nude in his polaroids in a tasteful and carnal way. There is always that fine line between good and bad taste, and I love him for walking that line.

ME: So, elegant and sensual can go hand in hand?

EP: Yes – look at Mollino’s interiors and what he was able to accomplish with them. He made beautiful polaroids that were found after he died. They will remain a mystery and I think of them as ghosts. Even in my own paintings inspired by his work, I soon thought to myself, ‘Oh my god, they look like ghosts’. They’re an archetype, and as we know, all creativity stems from the female.

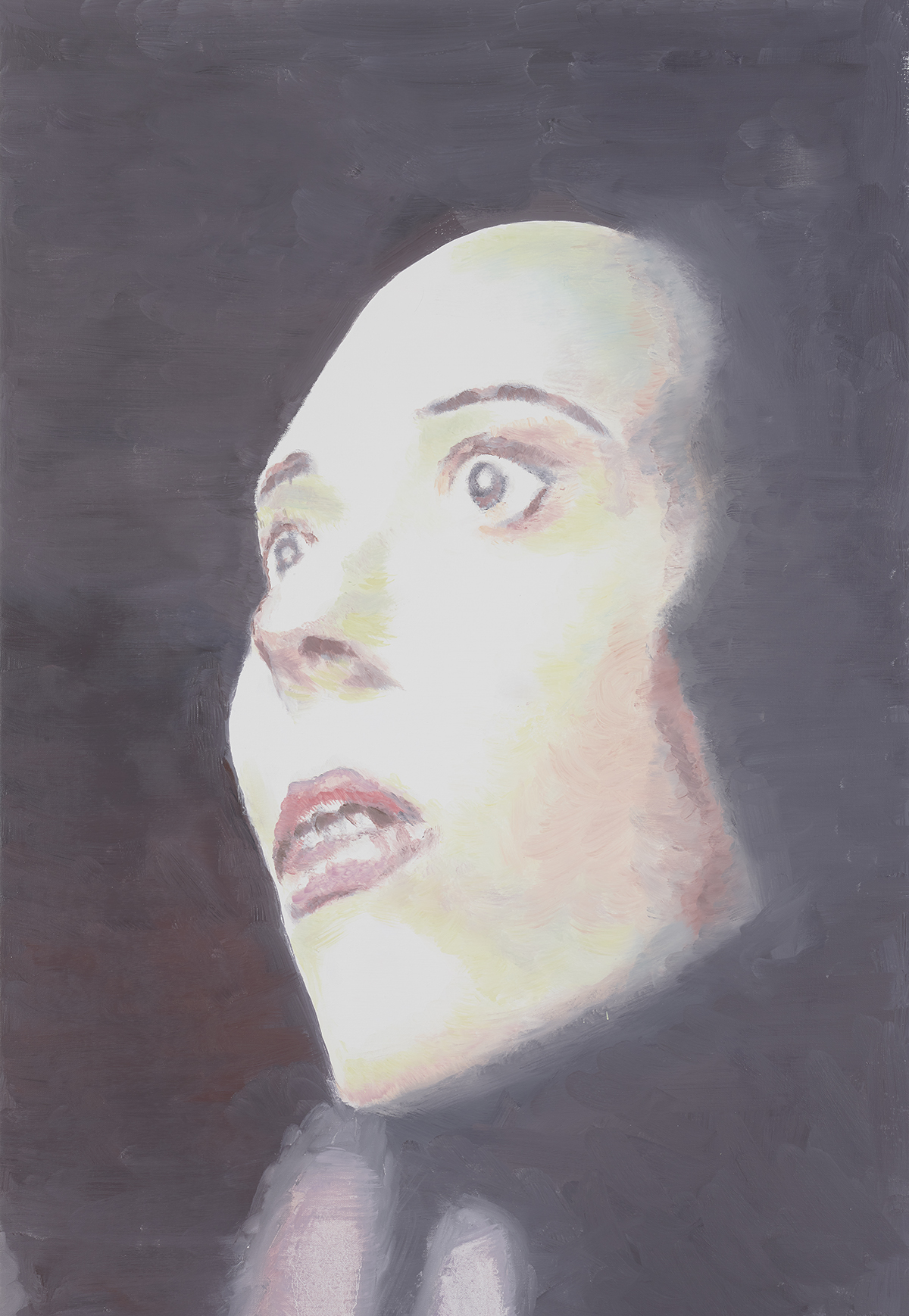

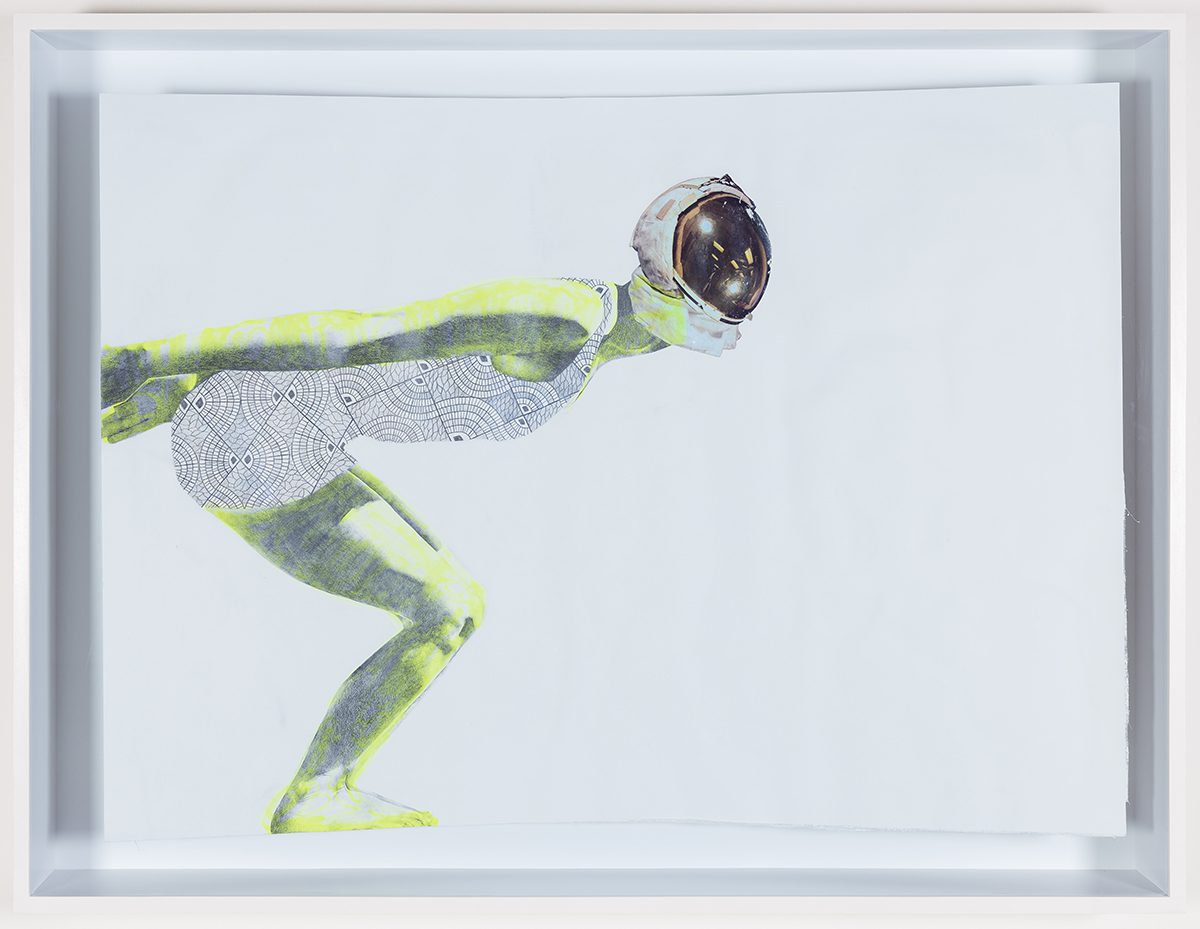

‘After Mollino (18)’ by Enoc Perez (2019), inspired by Mollino’s ghost-like polaroids and interiors

ME: Female is creation. Female gives birth. Female inspires.

EP: Yes, quite literally. If you look at Mollino’s national theatre in Torino, it looks like a vagina – the most beautiful thing. It’s also very powerful.

ME: Do you think the art world looks down on all matters ‘beautiful’?

EP: Seduction is mostly looked down upon, at least in my experience in the art world. The current moment reminds me of the mid-90s, when art became so political. My attitude to that was, and still is, that I think it’s necessary. Personally, I want to inspire. I want to make art that has soul. That, to me, is more mysterious than making just a statement or offering a one-liner. I am active politically in my community, but art is about love for me.

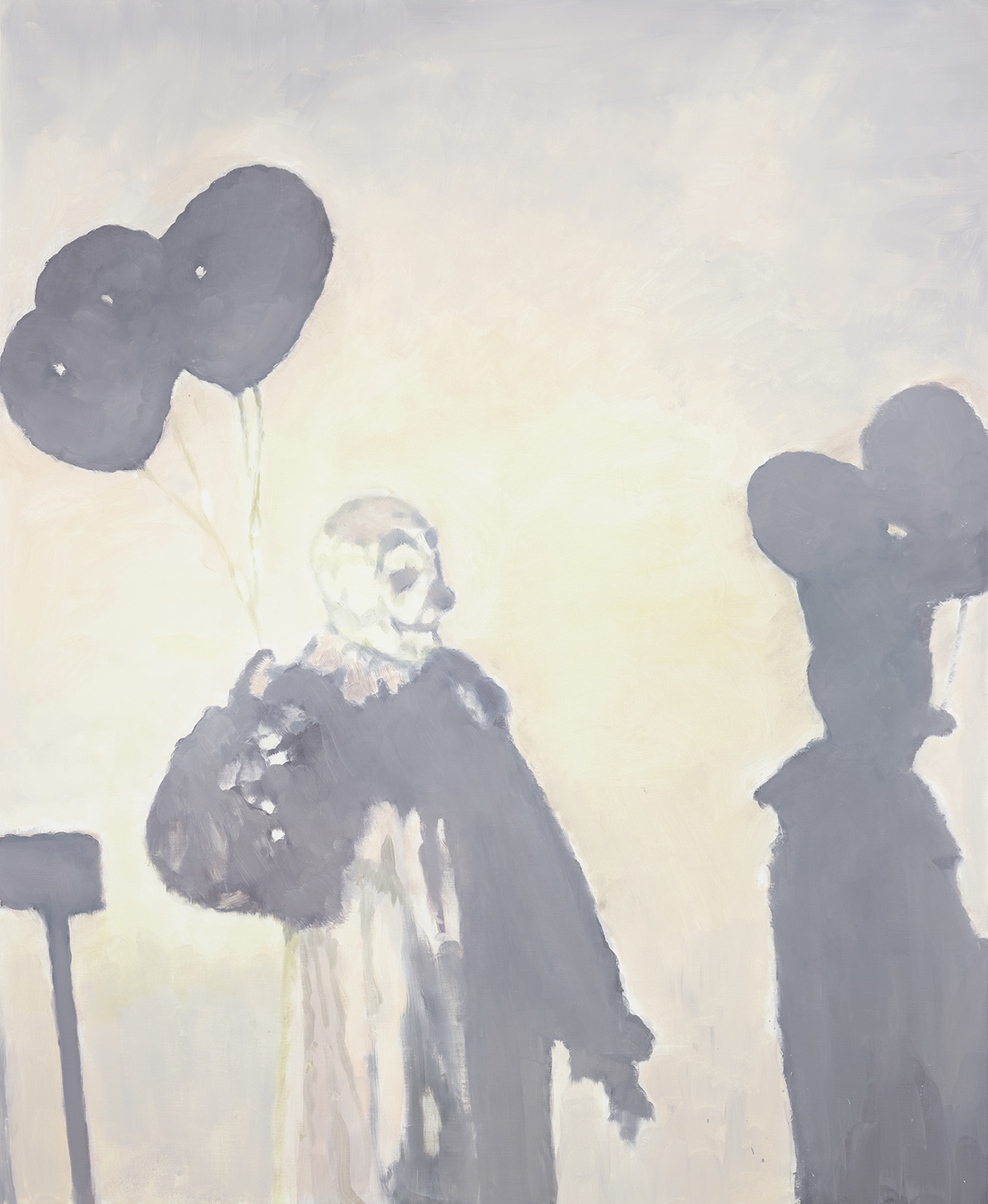

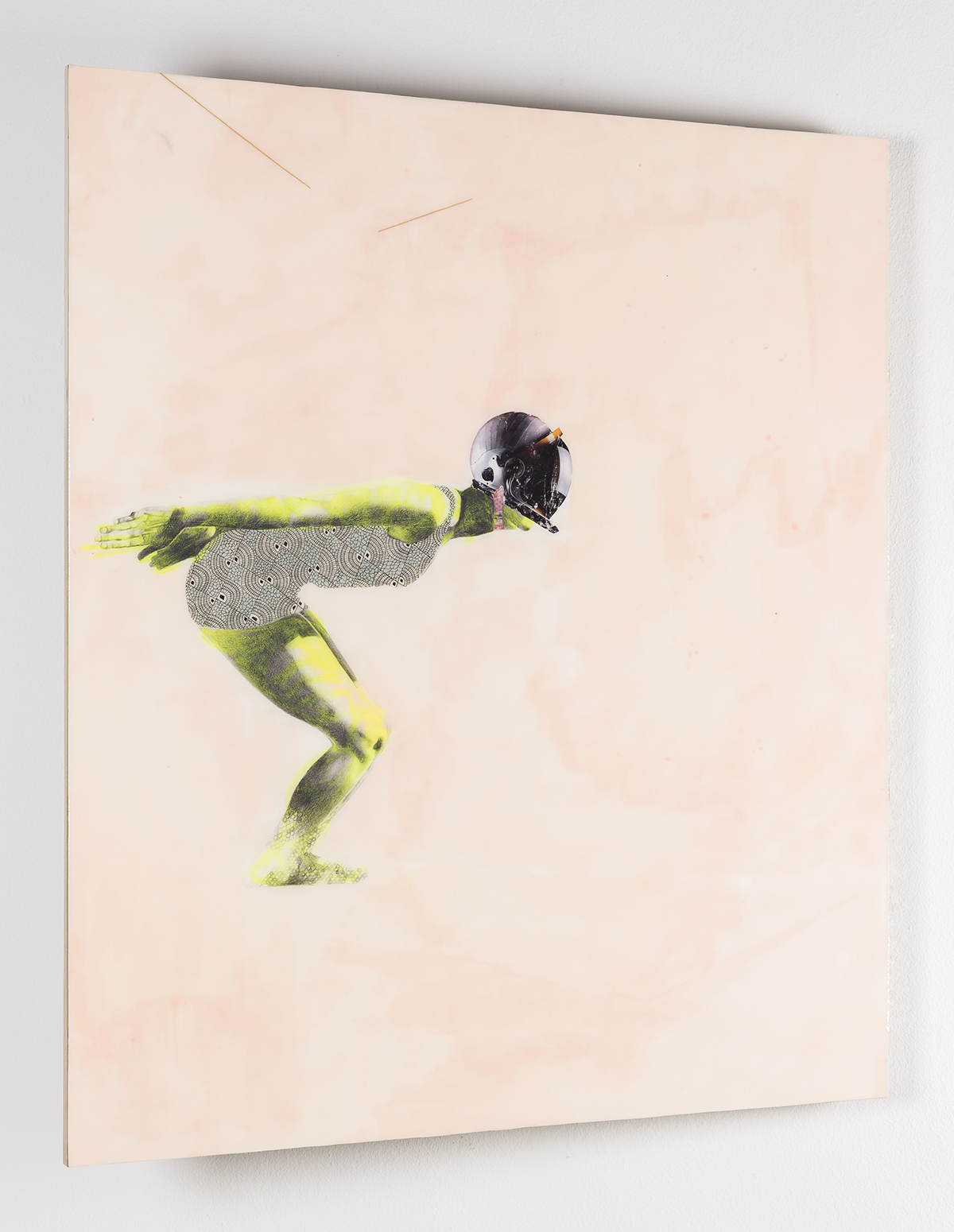

‘Untitled’ made by Perez with oil on canvas in 2024

ME: I also sense this idea of bygone past, some sort of melancholic nostalgia in your work, or a nod to sentimental elegance of the past which we seem to have lost today.

EP: I don’t know if it’s nostalgia. I think it’s about wanting to reclaim a time that only belongs to me.

ME: Your representation of this time looks a bit disjointed, like fragmented memories.

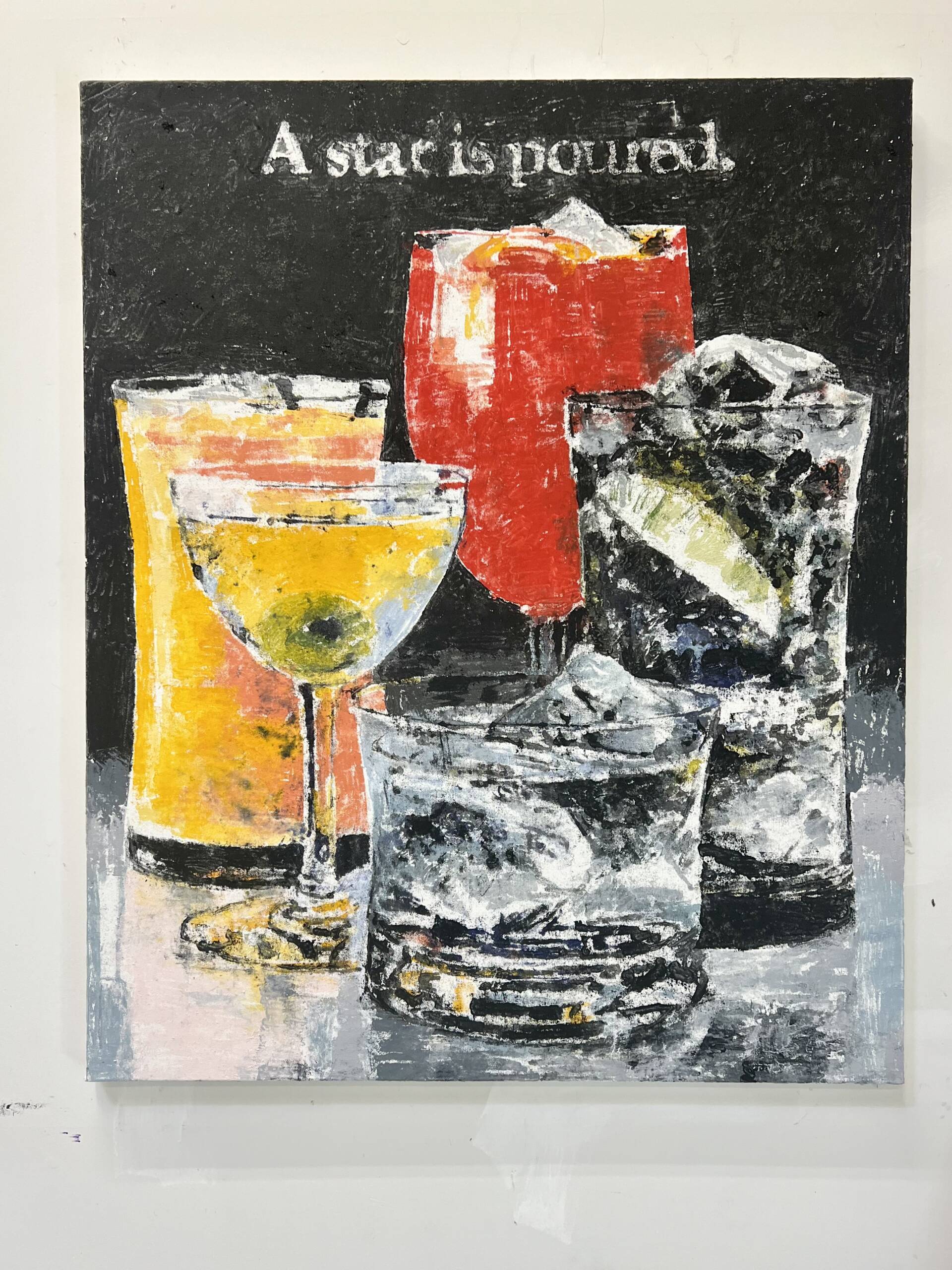

EP: It’s fractured, kind of like myself. When I started to do the Rum Paintings, for example, those were self-portraits. I was an alcoholic at the time.

ME: When did you become sober?

EP: When I had my first son, Leo. My wife went on a girls night out, and I stayed behind to take care of him. I almost dropped him while I was changing his diaper because I was so drunk. The day after, I made an appointment with a psychiatrist. It turns out that I’m OCD, and I was self-medicating. I’m now 17 years sober, and I can only now revisit my paintings from that time.

Perez in his studio, with his process captured by Maryam Eisler

ME: Addiction undeniably is very present in the creative community. What has sobriety done for you? How has it affected your life and work?

EP: The positive side is that sobriety allowed me to be a normal, better father to my children. Also, it has allowed me to properly look at my work in greater depth. I did a project for the Dallas Contemporary about the architect Philip Johnson. When I started studying him and found out about his Nazi activity, I called Tony [Shafrazi] and told him ‘I don’t know if I can do this. This guy was a piece of shit’. He replied, ‘I agree with how you feel, but it’s your job as an artist to critique and to tell the story’. That allowed me to get through the show, but afterwards, I didn’t want to do any more architecture paintings. Think about Johnson’s Glass House. The Glass House is an important piece of architecture for American culture. It was inspired by a house bombed to the ground that Johnson saw while visiting a Hitler rally in Poland. I mean come on!

Read more: At the ICE St Moritz, the world’s most glamorous car show

ME: Where do you find your inspiration today?

EP: I did some of my best paintings in my thirties, so how do I access the person that I was then? That was part of turning 50. At this point, I am competing against myself!

ME: But you are painting as you did, with sobriety. The canvas is ultimately your own skin. I am very intrigued by your use of calligraphy; even that is of the past.

‘Untitled’, 2024, oil on canvas

EP: Maybe I am allowing myself to do that more today. I am having a show in Hong Kong with Ben Brown with my Rum Paintings and I have used words like ‘Go Bananas’, encouraging the alcoholic to get worse! Or ‘it’s nice to know you’re loved amongst friends’ shown with empty bottles. Poetic, right?

ME: Poetic while it’s happening. Perhaps not so poetic the day after!

EP: I also still love the old advertisements. They look like Morandi’s still lives; they’re just like pop art. But ultimately, I like the landscapes because they’re very real, like fragmented memories. The landscape is the only thing for me that is real. And I see it as mine. The Caribbean is mine.

ME: At the end of the day, it’s your world, your imagination, your brain! You allow yourself that privilege. In this world of ours, you cannot control a lot of things. One thing you can control is you.

EP: Understanding the moment, I understand the freedom of being exactly who I think I am.

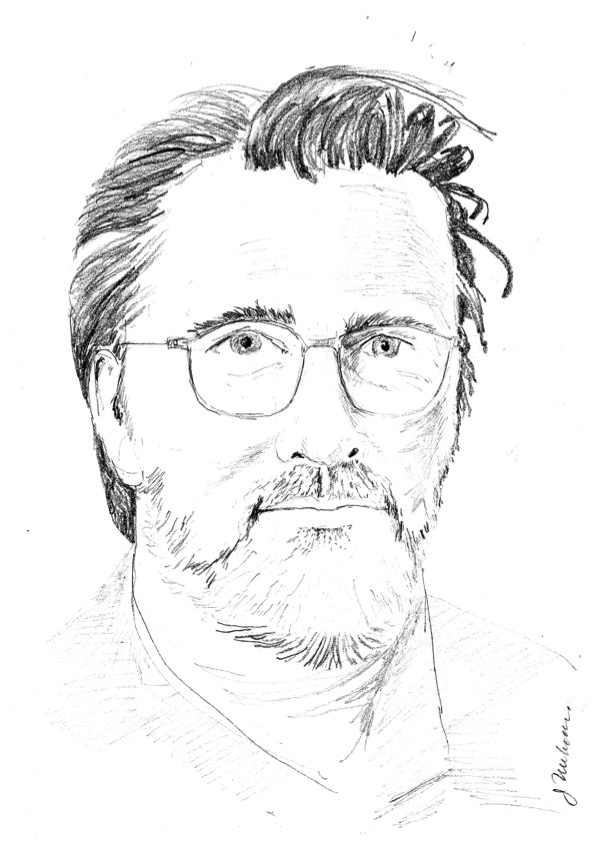

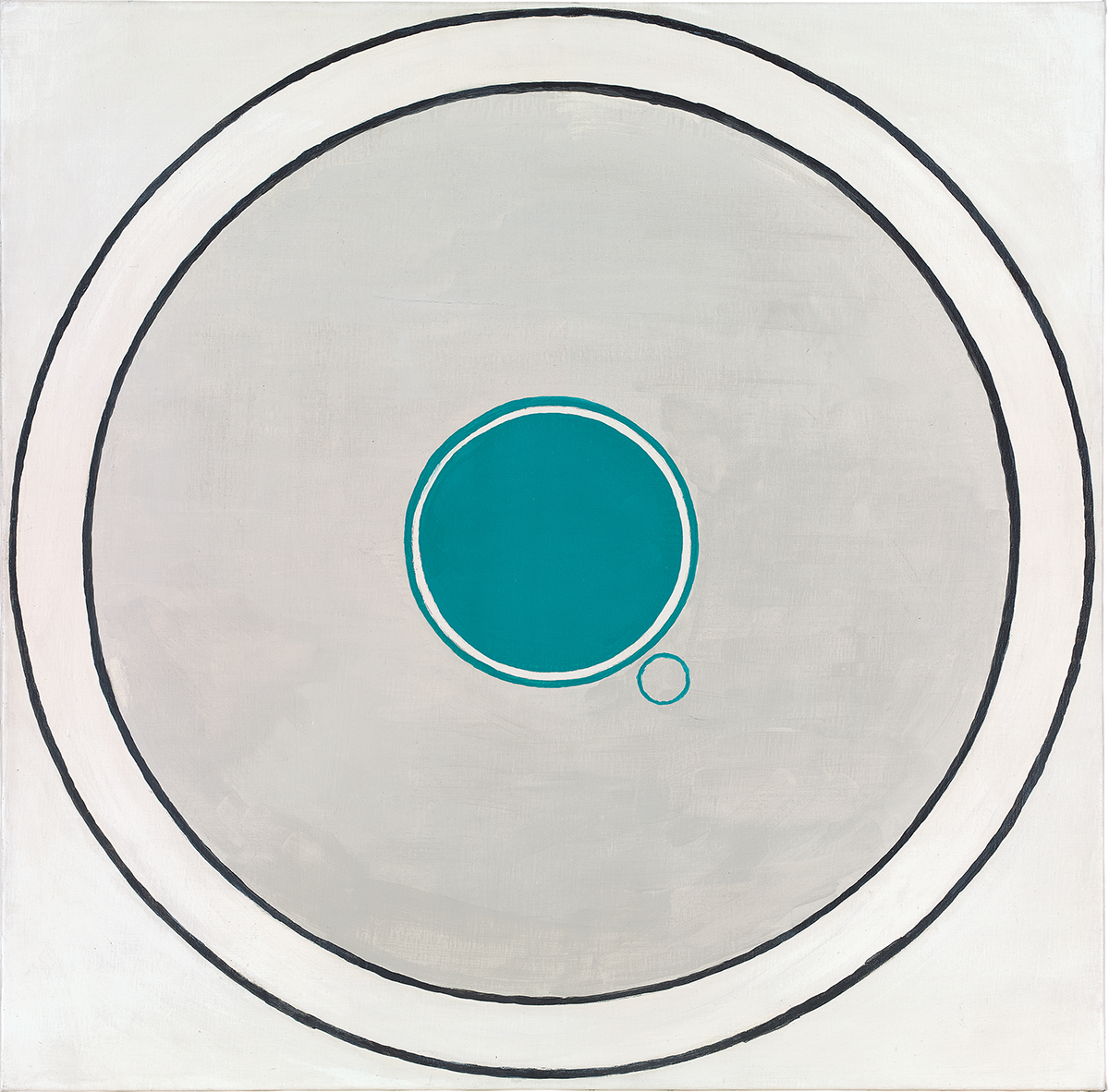

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

In the mid 1960s, Michael Craig Martin emerged as a key figure in early British conceptual art, later becoming the teacher of many of the YBAs such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas. Today, he is one of the world’s most prominent artists, known for his brightly coloured paintings and sculptures of everyday objects. Millie Walton speaks with him about colour, style and listening to his own advice

Recent Comments