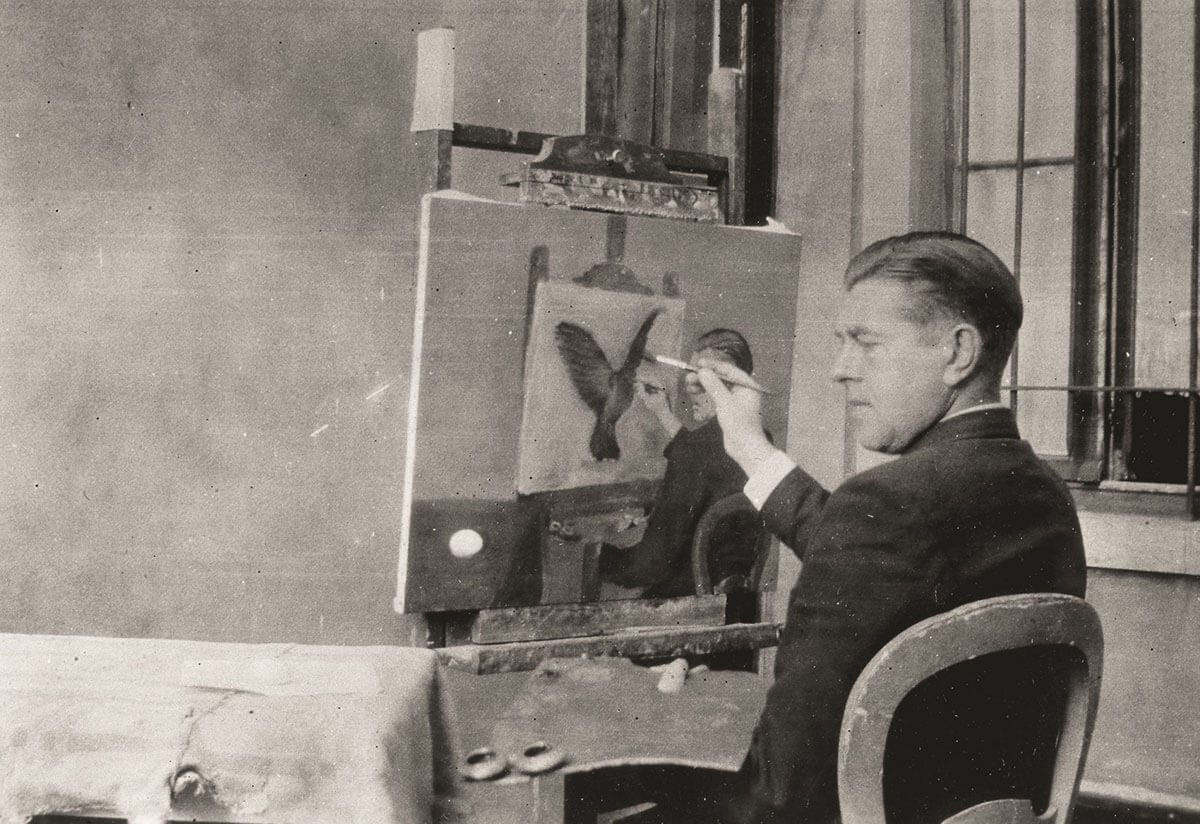

Marc Ferrero in his studio

Marc Ferrero’s unique practice of ‘Storytelling Art’ combines aesthetic styles and visual references from different artistic movements and cultures to create striking, narrative-driven paintings. His most iconic artwork ‘Lipstick’ first appeared on the watch face of Hublot’s Big Bang One Click last year, and this month, marks the launch of the latest edition in monochrome. Here, we speak to the artist about visual storytelling, the language of colour and man versus machine

Marc Ferrero wearing his Hublot watch

1. Tell us about the concept of Storytelling Art.

Artistic movements will always be a mirror of their generation. To me, a simple graphic representation doesn’t speak loudly enough to create big emotions, but stories touch many different sensibilities. Telling a story, means that you enter in the imaginary world of people. Nobody is passive in the face of a story, because it mixes two different concepts, inaccessibility and identification.

Each time somebody stands in front of one of my paintings they can relate to it through their own story; this creates a very dynamic relationship between the public and me as the artist. Faced with a graphic representation you are a spectator; faced with a storytelling painting you are an accomplice… it makes a big difference.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

I created the Storytelling Art movement because I thought the field of painting needed a new approach. The normal process for most painters is to start from reality, to create a personal vision. I reverse that process by starting from my imaginary world and creating an entirely new world that is expressed through stories and fictional characters.

Compared to the other visual arts, the evolution of framing in painting is close to zero. I purposefully try to create different framings in order to produce more dynamic images and suspense. Storytelling art is not a graphic style, it is all about interpretation. The fact is all paintings tell some kind of story, but with my work, nobody will discover its story through an audioguide… The story is expressed on the painting directly.

Fiction, manipulation and fusion are the main words of Storytelling Art movement. What could be more connected to the time we are living in now?

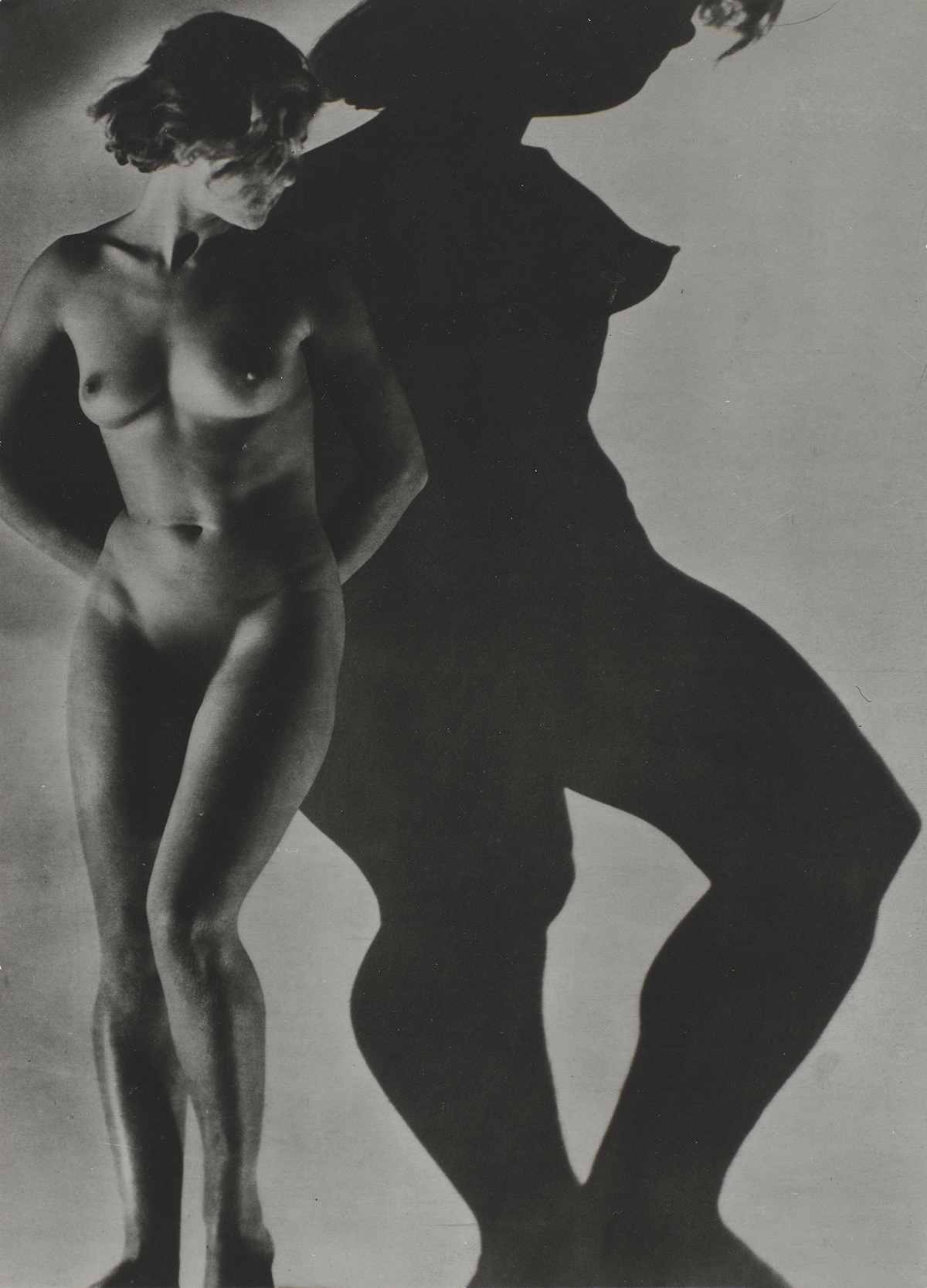

2. What’s the story behind your iconic artwork ‘Lipstick’?

The central subject of the LIPSTICK painting is a woman wearing large black glasses. In art history, when an artist wanted to create a feminine subject, he made round shapes. For me, what a woman says is as important as how she looks; this is the definition of a ‘modern woman’. My way to express that psychological reality is to use angles, lines, and Cubist forms through the glasses. The LIPSTICK rebalances all these lines because it is a symbol of femininity. All around the main subject, there are many different realistic portraits of woman, who express the different roles that a modern life can offer.

Big Bang One Click Ferrero Steel Red

3. How did you go about adapting the design for the latest Hublot Big Bang One Click?

The first time we met with the Hublot team in Switzerland everybody felt in love with my series of LIPSTICK paintings so it made sense to use that design. We worked as a team with Hublot’s graphic designer to translate the spirit of the painting onto a smaller scale. Usually, I work on a much bigger scale so I had to rework some outlines of the different figures around the central subject. To reproduce a painting onto a watch without trying to find the balance between the size of the dial and the spirit of the

painting itself would be a failure for sure. The strap is based on a stencil that I made specially for Hublot; it completes harmony of the watch.

Read more: How Hublot’s collaborations are changing the face of luxury

4. There’s a distinct graphic quality to your paintings – what inspired this style and what role does colour play?

Storytelling Art is a fusion of all kind of graphism on the same plane. This creates different values of time and space, which is absolutely necessary if you want to express several ideas or a specific story through a painting. Until now, an artist typically belonged to one graphic movement only, but to me, that’s old fashioned and doesn’t represent the time we are living in, but it all depends on the purpose of the painting. For example, my most recent paintings are based on abstraction to express a dehumanised world and the struggle of my characters in a society ruled by mathematical formulas and machines. I stick the characters onto the canvas in a comic strip, creating a fusion between abstraction and graphism which has a very powerful visual impact.

Colours have their own language in my work. For example, red is the colour of passion, audacious people and glamour, blue is the colour of transparency that expresses quiet places and the respect of tradition, but if you go to turquoise, it will express tropical places, holidays… Orange is the colour of energy, violet is the colour of dreams, yellow is a very convivial colour etc. Black and white fit with all other colours but never compete with them. Black has no movement and white is the colour of the future. I love to mix, and experiment with colours to create great harmonies.

5. Are you especially drawn to a particular type of story or character?

Mixing the verticality of a painting and the horizontal concept of a story opens up new fields of possibilities. The stories I’m working on go through the filter of my art.

Graphic tools offer me the possibility to divide a story in different sections of graphic styles. Pop art, for example, tends to fit very well with the heroes of my story. The ‘banksters’ of the story are expressed through Cubism. The world of the machines is treated through surrealism and abstraction, which fits

with the idea of a dehumanised world or the opposite idea of a dream world.

When I’m working on a story, I experiment. My studio is a laboratory, not a place where I copy myself. The type of stories and characters I love to create must fit with my imaginary world and my specificity of being a painter, but it could be a surrealistic modern fairytale or a kind of dream with a V8 engine.

6. What are you working on now?

I am working now to adapt one of my stories with movie producers in Los Angeles. The climax of the story speaks about a dark idol who has changed the value of time and created the acceleration of the world. It is a world led by magic mathematic formulas and machines. The heroes (Lisa L’aventura, Duke Spencer Percival, Cello Di Cordoba) have created a secret network called ‘La Comitive Society Club.’ All the members of that network are connected through another measurement of time, in which the time is not based on hours, but on emotions and colours. The time of human emotion will fight the time of acceleration… It is a story about the fight between humans and machines.

Find out more: ferreroart.com; hublot.com

Recent Comments