A portrait of artist Sam Falls in Maison Ruinart, the oldest champagne house in the world

American artist Sam Falls is known for the entwinement of nature in his works. The Ruinart Conversations with Nature artist 2025, whose works have been shown at institutions including the Pompidou, Fondation Louis Vuitton and MOCA, speaks with LUX Contributing Editor Rachel Verghis about art, the natural world and loss

Rachel Verghis: You grew up in Vermont. How did the natural world inspire you and your early art?

Sam Falls: I think I took the natural world for granted, it was embedded in me. It came out later creatively, but at the time it was pure enjoyment.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

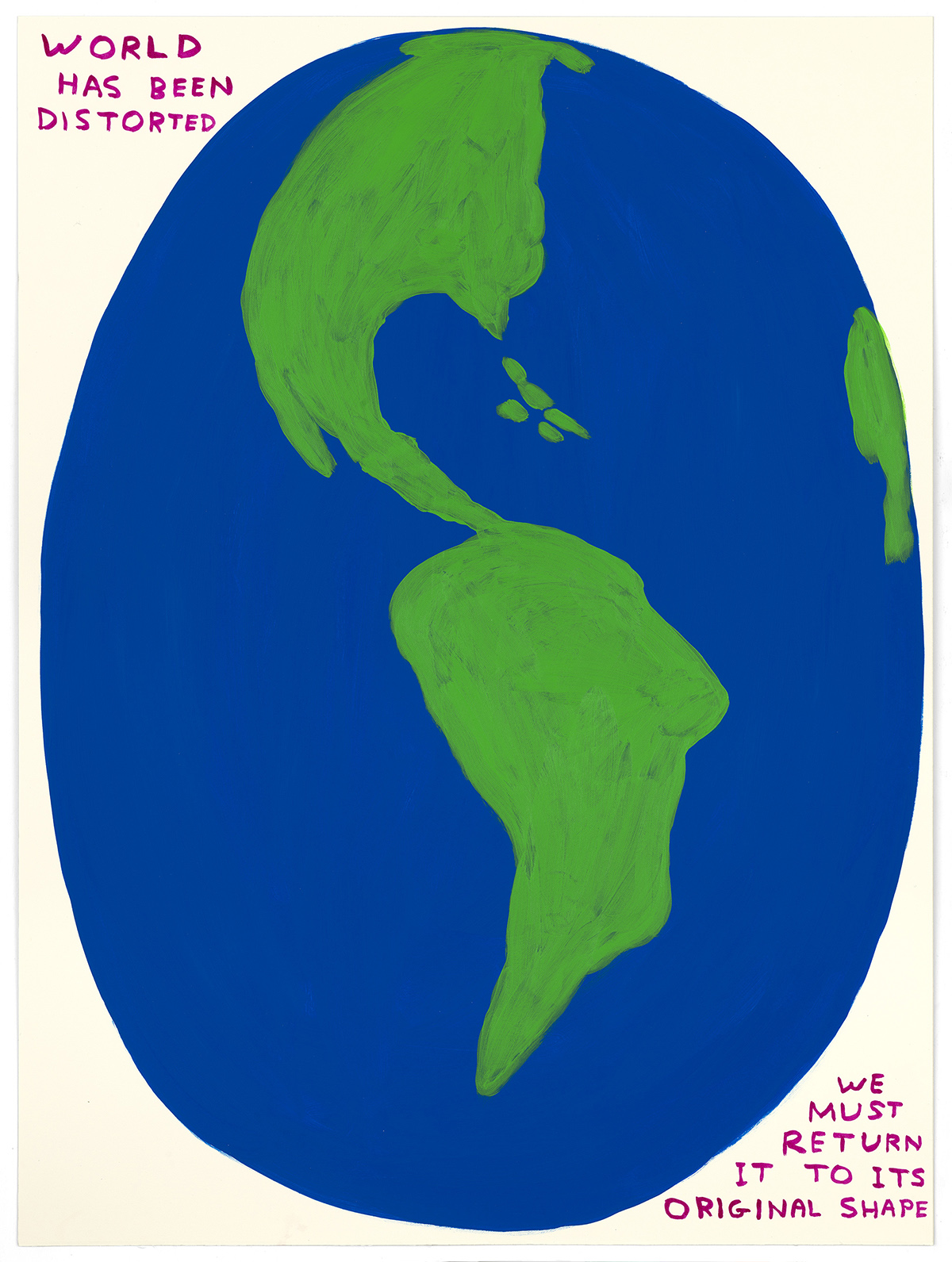

RV: Your contribution to the Ruinart Conversations with Nature 2025 cycle focuses on biodiversity. Is that a concern for you?

SF: It’s a constant for everyone living today, so it’s a big element of my work. It comes out through the subject matter, geography and biodiversity that are site-specific to each area I work with.

Rewilding by Sam Falls, shown at Frieze London

RV: The Ruinart work has been shown across the world. Do you follow the reactions to it?

SF: Yes, I’ve been following the reactions from Frieze Los Angeles, Frieze New York and Tiffany Pop Up in New York. I’m very happy with them.

RV: Is it important in your art to highlight not just nature but the threats to the natural world?

SF: It’s important to speak to the viewer, but also leave space for them. I don’t lead with politics, it’s inherent and available to the sensitive viewer.

Read more: Inside the Monte-Carlo Bay Hotel & Resort

RV: You experienced loss at an early age with the death of your mother. Is there a work of art from this time that has stayed with you?

SF: Yes, Christina’s World by Andrew Wyeth. It’s an American painting from 1948, and it’s in the MoMA. I saw that when I was 10. It struck me technically and emotionally and it stuck with me.

RV: Your children appear in your work. Why?

SF: Well, they emerged in my work as soon as they emerged in my life.

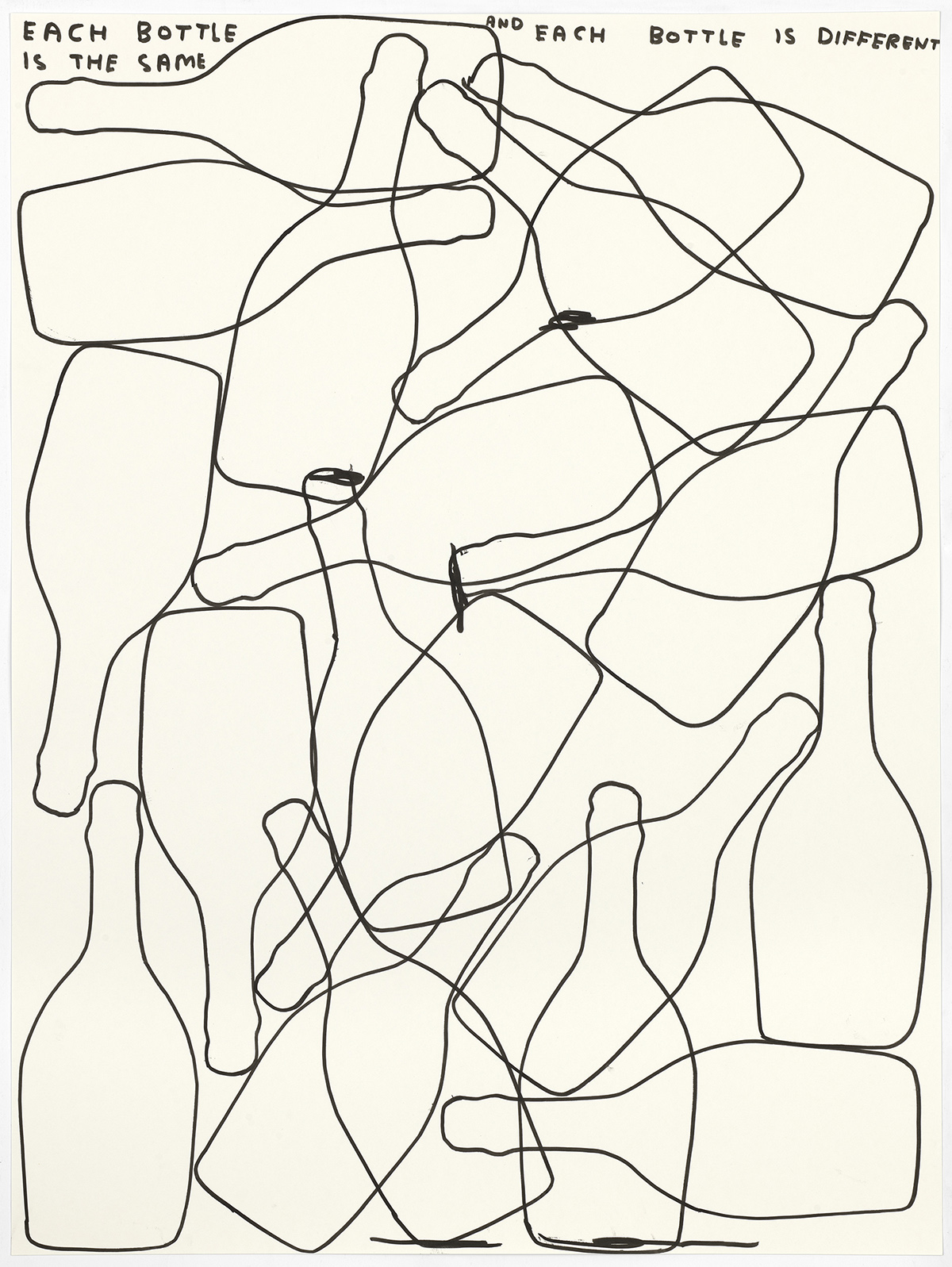

Sam Falls with his artwork King’s Crossing

RV: You once said your work had taken on a more melancholic tone. Why is that?

SF: I think the seasons and the passage of time in nature are more rapid than the seasons of our life. So it’s a microcosm of the passing of life through death that can be translated visually in art.

RV: You use nature to develop the canvas. Can you tell us about solarisation and photography?

SF: I made the decision early on to abandon the mechanical apparatus of photography and use natural sunlight. The process became a valuable source of connectivity to the viewer, because it is mundane and available to everyone.

Read more: A conversation with Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar

RV: Are you an environmental artist?

SF: I’m an artist using the environment, not an environmental artist.

RV: You have rejected the term “land art” to describe your practice. Why?

SF: Land art remains in the landscape. My art is a symbiotic creative process with nature. I remove it and leave no traces. The land is available for the next human or animal to experience it differently.

The process of creating King’s Crossing, made from nature and in nature

RV: What one element remains constant throughout your work?

SF: I would say, care for the viewer and also connection to the primary source.

RV: Is photography still apart from fine art?

SF: It became so familiarised it’s now accepted. But because it is a wider cultural phenomenon in the economy and the capitalist language, it is problematic. I use its representational assets as they apply to art history, rather than to the language of capitalism, integrating it fluidly.

RV: You once said, “Time is the thing that gives me the most anxiety.” Why?

SF: Well, because it is a march to death!

RV: In your practice, is decay a constant?

SF: Yes!

Recent Comments