Liza Essers and Durjoy Rahman in discussion at Goodman Gallery, Mayfair, London

In the first of our series of online dialogues, Liza Essers of Goodman Gallery and South South speaks with philanthropist Durjoy Rahman about the western eye on art, and the future of culture in the Global South. With an introduction and moderation by Darius Sanai and created in association with the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation

History is always written by the winners. Whether or not that is true, there is more than an element of truth as far as art history is concerned. The West, home of most of the world’s wealth for most of the past millennium, is where the biggest auction houses, collectors, galleries, institutions, and market-makers are based. When the average LUX reader thinks of art history, they are more likely to think of Michelangelo or Monet than Khmer sculptors or 12th century Chinese visual artist Zhang Zeduan.

The art fair is now a global phenomenon, and Art Basel and Frieze, the two biggest players, have editions in Hong Kong and Seoul, as well as London, Paris, Basel, New York, Miami and Los Angeles (note the weighting there between East and West). But they are American and Swiss-owned organisations driven by legitimacy from heavy-hitter galleries in New York and London. When Abu Dhabi wanted to gain instant credibility in the art world, it opened a Louvre (with a Guggenheim coming soon).

Yet art did not start in the West, and is unlikely to end in the West. One of the most significant organisations seeking to loosen the western grip, and accompanying neo-Orientalist viewpoint, in the art world, is South-South. Co-founded by the esteemed Johannesburg-based gallerist Liza Essers, owner of Goodman Gallery, who represents William Kentridge, among many others, it bills itself a resource for artists, galleries, curators and collectors across the global south.

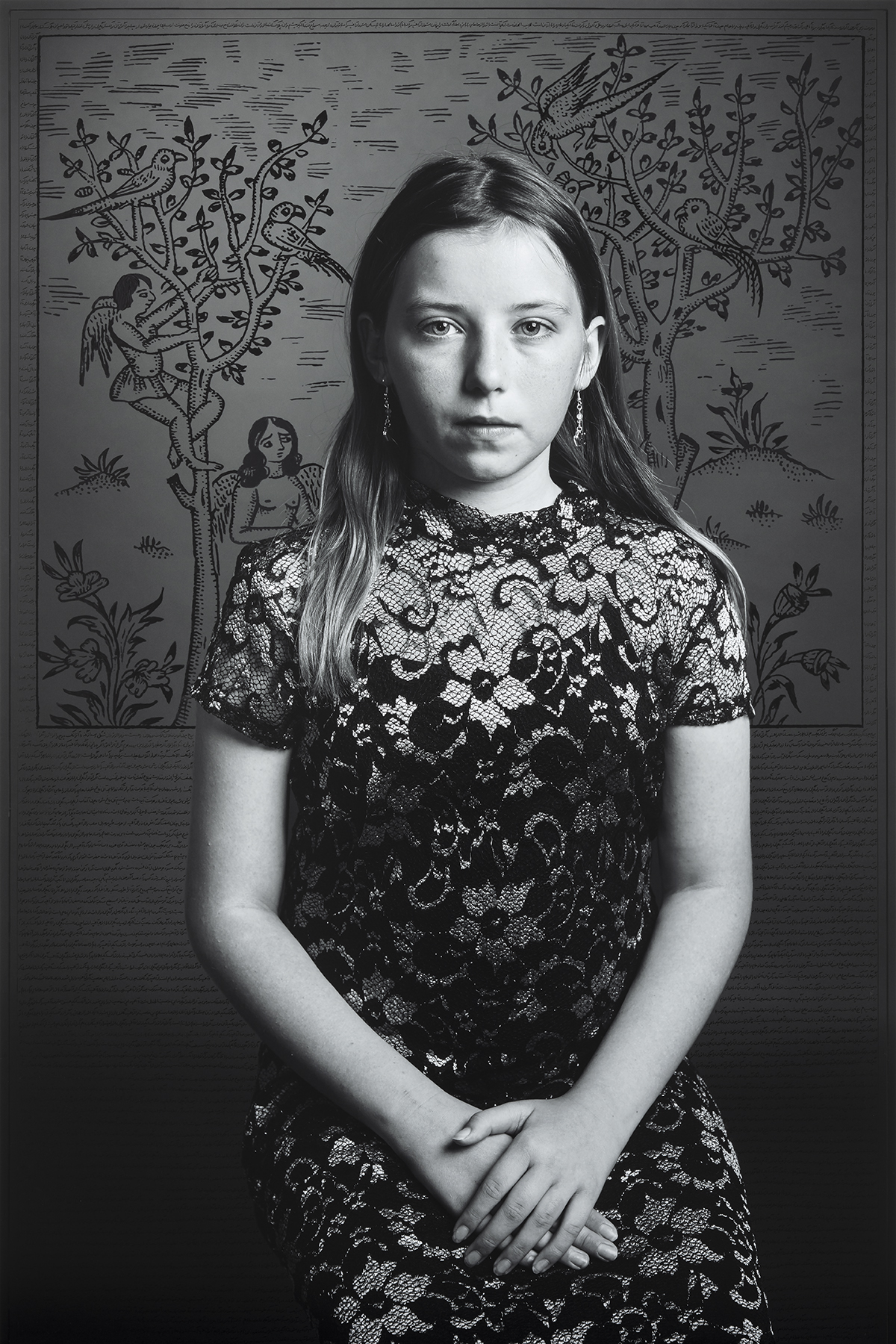

Liza Essers. Photographed by Anthea Pokroy. Courtesy Goodman Gallery

For the first in our series of online dialogues, we brought Liza together with a growing force in the rebalancing of east-west art relations, Durjoy Rahman. Founder of the Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, Durjoy is a multifaceted collector and philanthropist supporting artists and institutions across South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. The foundation supports a residency at Amsterdam’s Rijksakademie, is launching a new partnership with India’s Kochi Biennial and London’s Hayward Gallery, and supports the esteemed Sharjah Art Foundation, among many other initiatives.

The dialogue between two intriguing leaders in art in the Global South was moderated by LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai, himself from Iran, in Essers’ Goodman Gallery in Mayfair, London.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: Liza, you set up South South as an organisation which does not just promote dialogue and art action, but additionally serves as a way to provide artists and galleries with a new way of interacting and selling work.

Liza Essers: Absolutely, it goes back much further than I think most people realise. South South started in 2010 after visiting Brazil and being completely inspired by walking through the streets of Sao Paulo and thinking about Johannesburg. These two places I felt had shared histories and realities of their current situation. South South then started as a curatorial initiative that I began with Goodman Gallery. There were two strong curatorial initiatives; South South and another project called In Context, that was looking at the dynamics and tensions of the place. I was really interested at the time in the term the ‘Global South’ which was very much established by Lula da Silva, as an economic term around foreign policy. I suppose my background in economics got me thinking about seeing these real distinctions within the Western art market and The Global South, in a context of underlying political and economic realities. Over the last 12 years, there have been big multi-place projects with galleries around The Global South.

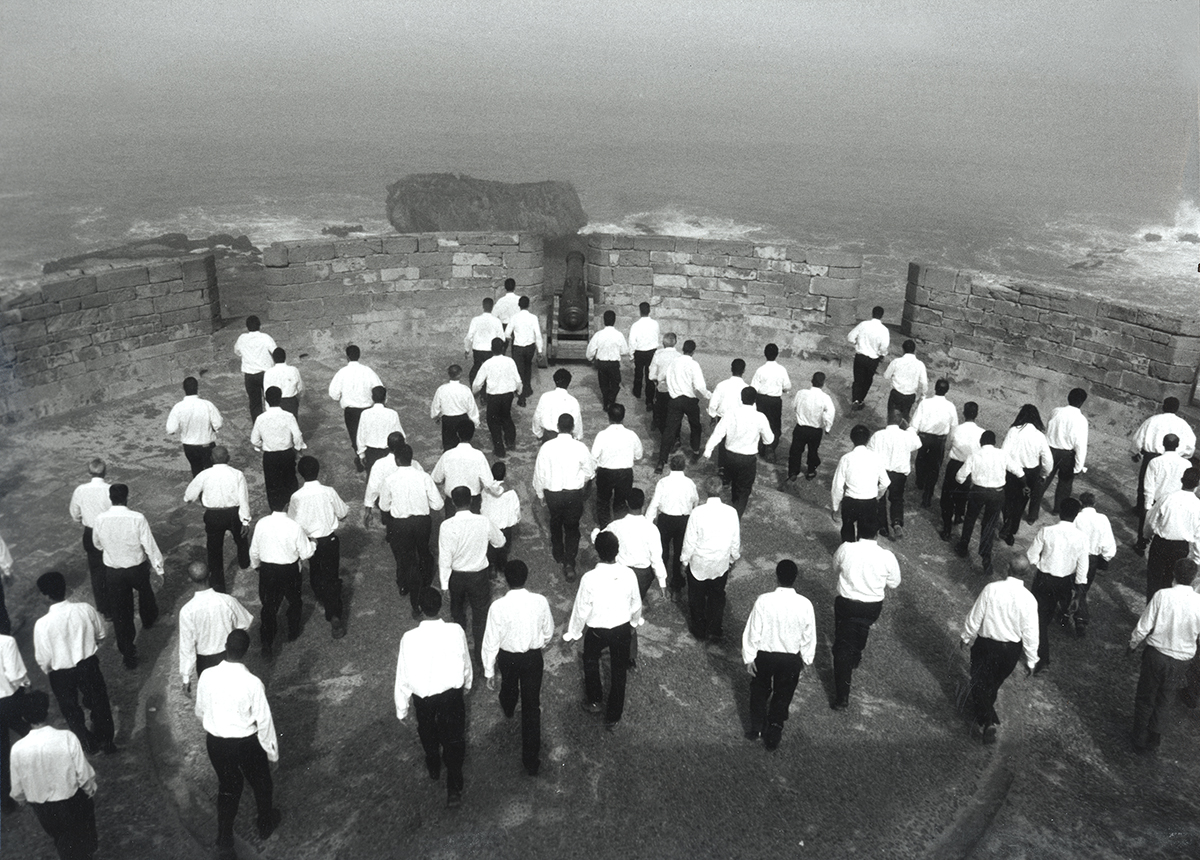

Samson Kambalu, Beni Flag- Sovereign States (this is not what I meant when I said bang bang), 2019

LUX: Durjoy, do you see any parallels between the work of your foundation which is focussed around supporting south Asian art, artists and organisations, and the work of South South?

Durjoy Rahman: Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation (DBF) was founded in 2018 and our mission was to support artistic, socially-activated practices. Not only do we promote South Asian artists, but also all across The Global South. There are many similarities between artists living in Asia, Africa and even South America with a lot of their work being interwoven as they live in similar social positions and environments. We also work with artists from Africa whose practices are aligned with social contexts that exist in South Asian countries like Bangladesh. For example, we hosted an artist from Ghana whose work we collected back in 2017 and his practices are very similar to those that we see in Dhaka. When I found his work and I realised the similar socio-economic environment, we started working with him and donated his work to a museum in the Netherlands for his first show in 2018, which is now in their permanent collection.

LUX: As part of the driving force behind the gathering momentum and support for artists from The Global South, is there a need for more organisations like yours?

LE: I feel that there is a need of course, but more importantly, we need collaboration. Instead of everyone trying to individually reinvent the wheel, the whole art world needs to shift together. Collaboration is so much more powerful if people work together to achieve better things for the arts.

DR: I agree, but I also believe that we need to make these artists more visible in their role throughout European history. A lot of South Asian or African artists came to Europe in the 50s and had shows alongside Picasso or Miro, there was a real cultural exchange. Unfortunately, due to the economic situation right after the end of colonial history, in Asia we became less visible and prominent. There is an urgency to work together to establish the position of the global south so that we are equally important in the development of modern art.

LE: Absolutely.

SP-Arte 2022

LUX: Is there a challenge for people to become artists in some countries in the global south, due to the lack of recognition of an art as a viable career? My father, who was Iranian, was a huge art lover and collector but he would have been aghast if I had wanted to actually be an artist.

LE: You are spot on. It is much better than it was, as there are more museums and contemporary art spaces, but there is still a long way to go concerning cementing arts and culture as central to education. For example, in our school system in South Africa, it isn’t part of the mainstream education system, so it is not something that kids are even growing up with. People who are struggling and are below the breadline want their kids to go and become professionals rather than artists due to the perception that they would be unable to make a living.

DR: Regardless of which class, middle or upper, the concept of your child having an arts career, has always been looked at with scepticism from the parents. Every family wants their children to be prosperous and this is not something that has traditionally been considered with an art career, as it is a high-risk option. I think, however, that the times are changing with the increase of museums and art spaces. I think more and more people will be interested in creativity and artistic practice because of the larger income generation.

LUX: Let’s talk about the Western Eye on the Art world. People might say “I’m going to go to an African Art Fair” or “going to look at some Asian Art” but they wouldn’t talk about a “European Art Fair”. Should that change and how important is it?

LE: I think it is of critical importance and one of the main reasons why I felt that it was not constructive or positive for Goodman Gallery to associate with the term African Art Fair. I do think we have to move away from the confines that come with these labels, and consider art as a global language, which is about the human condition globally. I think it is too driven by economics and markets in the West.

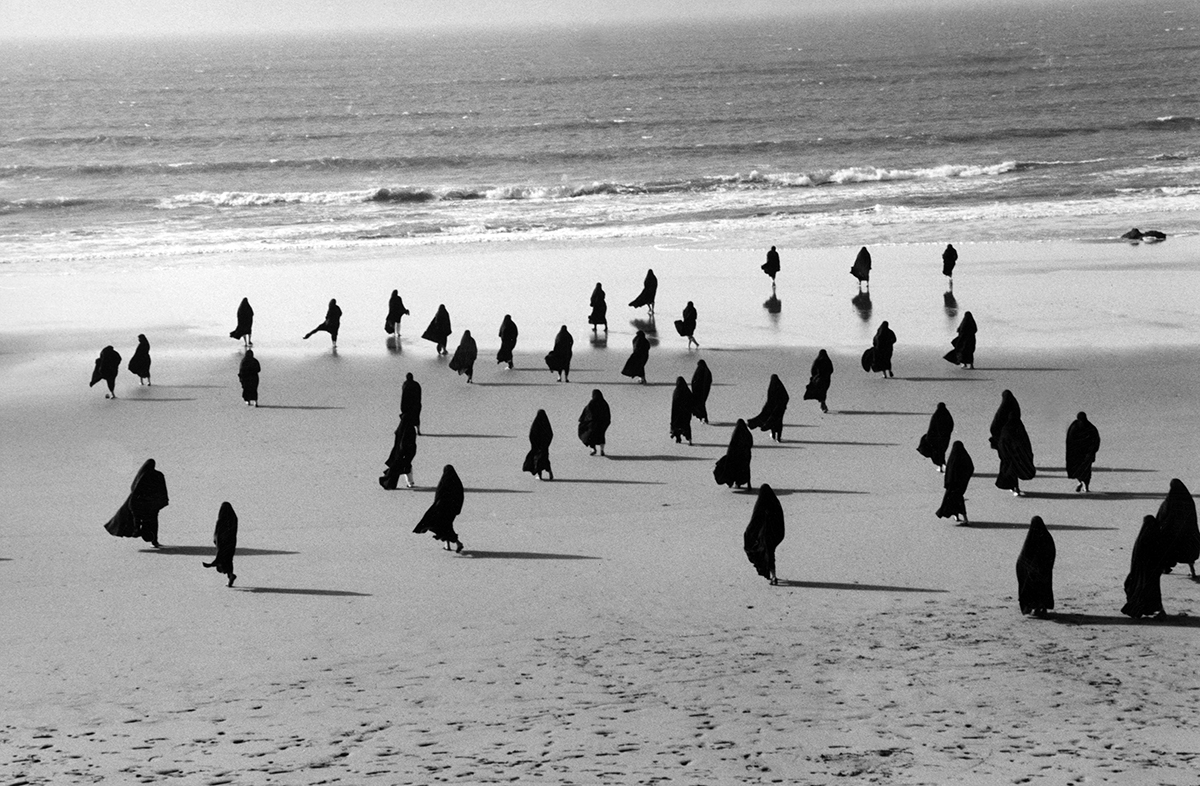

Yinka Shonibare CBE, Un Ballo in Maschera, 2004.

DR: I agree! Art is global – it’s not about Asian, African, American. I also think that it has a lot to do with the influence of a lot of organisations that have a ‘South Asian Sale’ or ‘Asian Art Week’. It doesn’t matter how much we think that the art is global if the branding or wording pushes us further into the corner that we want to come out of. This seems to be shifting as the West is looking more at the East. Of course, it will take time, but eventually one day art will be global, and for now we must work together to create global branding rather than regional.

LE: I will say that where it has been useful, if one thinks about a counterpoint, is something like the Johannesburg Art Fair. There has been a benefit of this as it becomes an educational opportunity to build a local collective and for artists to make money. I think we need give a little bit of credit as these regional fairs help to build art markets within our particular communities where there is an absence of cultural institutions and big museums.

Read more: Alan Lo On The Next Asian Art Hotspot

We also encourage these regional fairs to focus on quality and moments, bringing international art into the programme. That’s why for the Johannesburg Art Fair this year, being on the advisory board, South South have an interesting role in creating this shift. We included a video program with international galleries showing artists within the art fair context. It would be too expensive for galleries to show up at international art fairs, but it is an interesting way for audiences to experience international artists and galleries through the South South platform. This has been successful at art fairs this year as audiences can see international art.

LUX: Do you think there is a form of colonialism within the art world, whether conscious or unconscious, from major galleries and auction houses?

LE: I do feel so, although this is probably a bit controversial. We have all got a broader responsibility within our lifetime that I think we generally don’t necessarily take seriously enough and many of the big galleries will colonise or take the artists from the galleries in the Global South. They could be supporting artists and the community in a more productive way. Many galleries want William Kentridge, for example, but how many of them have actually shown up in Johannesburg and understood the context. It just becomes about brands and markets.

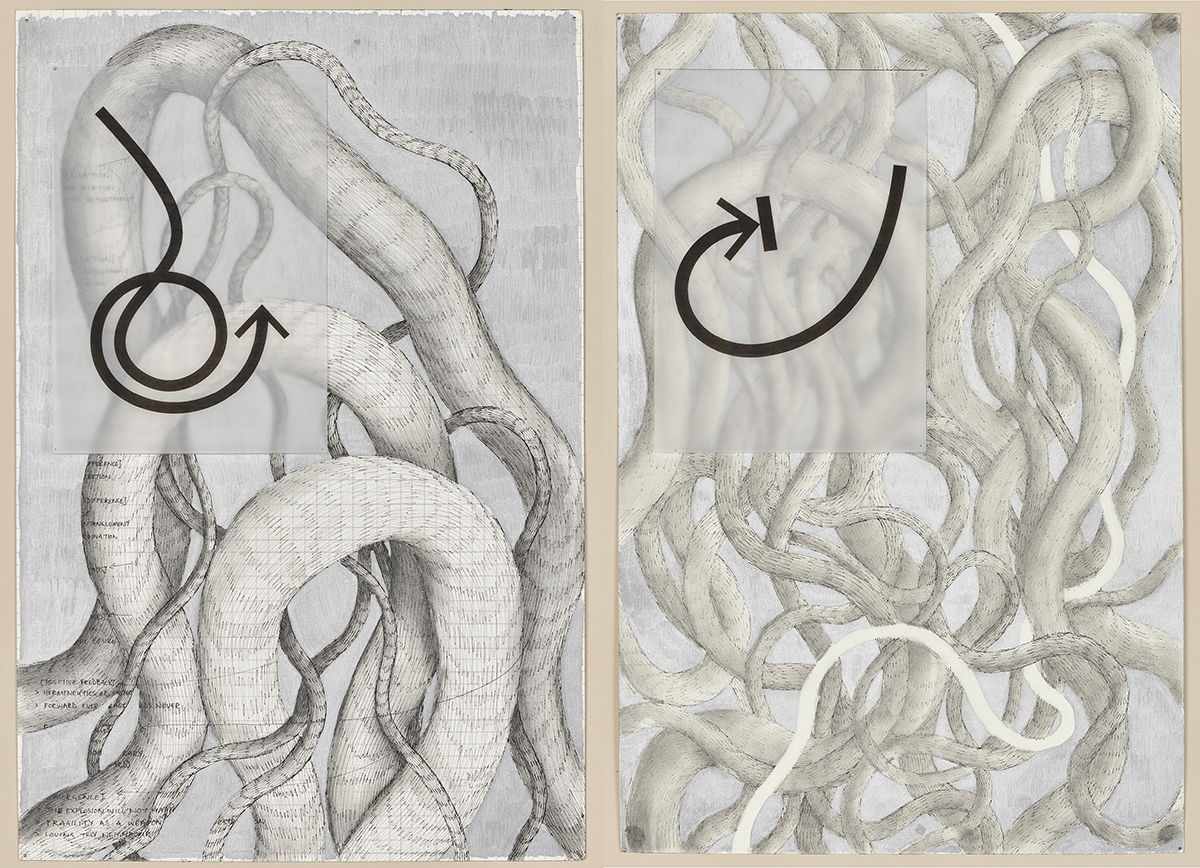

Nolan Oswald Dennis, notes for recovery (touch), 2020

DR: In these galleries the financial aspect is a very big factor and a lot of emerging galleries are not able to participate in the big fairs. I think it is more about the financial strength of certain galleries and their ability to dominate space rather than colonialism.

LUX: Looking to education and the consideration that many people who move in the Western art world have Art History Degrees, a.k.a an education dominated by the teaching of the European History of Art and 20th Century US history. Does there need to be a shift in the way the history of art is taught and its many origins and truths?

LE: Definitely – I think that is one of the fundamental pillars of South South. It is much more about the curatorial aspect and the archive than it is around the selling of art. We have a whole archive section on the website where we are looking to gather in one central place and repository of the history of art from The Global South. It is amazing how all of these histories or particular moments in The Global South are not written into the history books, so the idea is really around gathering all of them into a central space.

DR: Information, which is a big factor, was not available or generated in our part of the world – it always generated from Europe, for example there was a huge printing industry in Germany. Due to the fact we, politically and financially, relied on the Western world, they became the authority of information through their dissemination. That is where a lot of things have been influenced, it is not because of colonialism but because of the financial strength they had, that they told their own story, rather than The Global South.

Installation at FNB Art Joburg

LUX: Liza, Durjoy, what would you like to ask each other?

LE: For us at South South, we are now in a place where we want to recognise that post-covid we are returning to ‘business as usual’ with exhibitions and art fairs. I suppose what I am struggling with is how to make South South post-covid meaningful in the art world going forward, when we have to deal with the art world in its old form which is being on the road every few weeks for another fair. I am interested to know if you have any ideas while we are in a moment of reflection on how to move forward and make a success out of it?

DR: The South South platform must be balanced between commercial and non-commercial activities, because ultimately no activities can be successful long term if the business is not culturally sustainable. I think that covid has given us all a realisation of what the world needs, but I always say that art is an object too. We need to ensure its commercial viability. But on the other hand, what we have seen pre-covid at the art fairs is everything attached to the commercial sense. If we can encourage all the stakeholders and beneficiaries associated to work together to create a programme that is designed to give The Global South a stronger presence, I think that would be brilliant and give more representation and visibility to these artists.

Find out more:

Recent Comments