Steam cooking can preserve the nutritional value and flavour of delicate vegetables such as mushrooms

The ancient art of steam cooking has gained new impetus with the revolution in healthy and mindful cuisine. Lisa Jayne Harris looks at the artful kitchen innovations from design-led German luxury appliance maker, and chefs’ favourite, Gaggenau

Alice B. Toklas, the celebrated 20th-century literary salon hostess, had one golden rule for cooking: “one must respect the quality and flavour of the ingredients”. Steaming is the most direct way to achieve her objective; it is an efficient way to cook that leaves the food tasting exclusively of itself. Just consider the simple excellence of steamed asparagus with French butter, one of Toklas’s stand-by dishes for entertaining.

Phil Fanning, the executive chef and owner of restaurant Paris House in Woburn and Gaggenau culinary partner, agrees: “You’ve got nowhere to hide with steam: It’s all about the quality of ingredients.” This is essential when you are working with delicate seasonal vegetables like asparagus, new potatoes or peas, but it is just as significant with good quality meat, baked goods or pastry.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

However, healthier eating is another powerful motivator behind the steamed food trend. Boiling vegetables reduces much of their nutritional qualities, such as vitamins C and B1, and other mineral salts readily dissolve in water. Lightly steaming does not disturb the food’s cellular structure or its aromatic compositions the way boiling does, so you preserve more vitamins as well as the colour and texture for a more health-conscious cuisine. “Gentle steam cooking can actually improve the nutrient status of food like asparagus, spinach and tomatoes,” advises registered nutritional therapist, Catherine Arnold, “It makes their nutrients more bio-available to the body.”

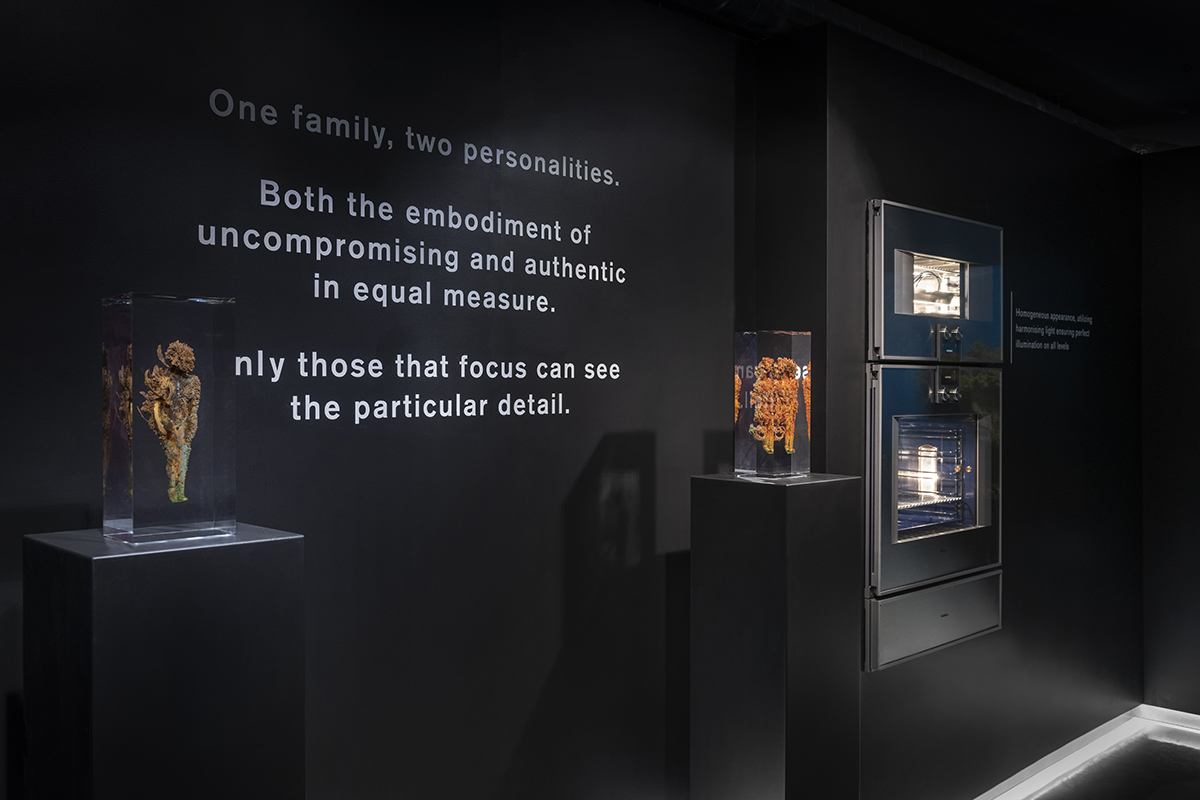

Gaggenau’s 400 and 200 series combi-steam ovens are ideal for the precise cooking of seafood

Gaggenau has pioneered steam cooking in the home for the past 20 years and continues to do so, including combination steam ovens: “Whether you’re cooking in pure steam, or in combination with traditional heat, you’re getting the health benefits of steam cooking, as it maintains food’s nutrients, colour and shape,” says Gaggenau’s category manager, Simon Plumbridge. Steam can improve other healthy eating habits such as juicing, too: “Our juice extraction setting gently steams hard-skinned citrus fruit such as oranges, so you get a much higher juice yield without impacting nutrients.”

Steam cooking is also gaining traction with chefs and home cooks because of the innovations in steam-cooking technology. For all its benefits – puffed soufflés, sumptuous bread, those crisp layers in a croissant – mastering the technique used to require an intimidating level of precision. Today, keen cooks are investing in internal temperature probes, gadgets and state-of-the-art appliances to emulate high-end restaurants at home. “The UK’s food scene has massively improved in the past 30 to 40 years, and this growth in skill and quality is reflected in passionate home chefs’ kitchens too,” Fanning reflects. Our private kitchens are becoming more technologically advanced, and ovens that enable amateurs to cook like professionals are both a luxury and an enabler of creativity.

Embracing both the old and the new makes us all better cooks. “Lots of traditional techniques benefit from having precise control over the humidity,” says Fanning. “Take bread for example. For the perfect crusty baguette, you need about 30 per cent humidity for the first five minutes and then very little for the remaining bake. In a traditional convection oven that requires guesswork, but it’s easily and consistently achieved in a combi-steam oven.” Brands like Gaggenau are making this trend for precision steam cooking more accessible. Their combi-steam ovens can be controlled to within one degree, which continually revises the estimated cooking time based on temperature-probe readings from three different sensors. There is no more guessing: “Steam in its basic principle is an ancient way of cooking,” says Plumbridge. “But controlling the level of steam in combination with a fan is only achieved by modern technology – and that’s what brings professional results into the domestic home.”

Read more: Fashion designer Erdem Moralıoğlu’s guide to east London

Steam is also about convenience; rather than waiting for an oven to preheat, a good steam oven heats to temperature immediately. When you combine that with smart, Wi-Fi-enabled technology that lets you control the oven remotely from your office, or even set the bread to prove whilst you’re watching TV, you have all the benefits of ancient cooking just a voice command away. “Connectivity in the home has a lot of momentum at the moment,” Plumbridge observes, “But we’re more interested in future-proofing, so our ovens have the capacity to integrate with apps on any system such as Alexa or Cornflake smart homes.”

As much as new food trends are about keeping pace with technology, steam cooking also allows you to take your time. Next generation combi-steam ovens can sous-vide for up to almost 24 hours on a mains-connected water system or 11 hours with a tank, and cooking meat low and slow with a good level of humidity means it won’t be subjected to heat expansion and contraction, allowing for a more tender and juicy dish. Chefs also use steam to impart more subtle flavours into a dish, laying herbs under a piece of salmon to infuse the fish or steaming couscous in a traditional couscoussier, in which spices, onions and meat cook in the lower compartment and impart their flavour to the grains above.

“Remember that with a combi oven, steam doesn’t have to be 100ºC,” Fanning advises. “You want to cook vegetables as quickly as possible at that temperature, but steaming a piece of turbot at 60ºC or even lower will give you a much more delicate result. Oxtail or lamb shanks can be very gently cooked sous-vide in a combi-steam oven for hours with virtually no chance of overcooking, and duck legs, pork belly, haricot beans or lentils – if vacuum packed with a fat or oil – can be very gently and accurately made as a confit.”

Icelanders have steamed their bread buried next to hot springs for generations and Chinese steaming baskets have been piled with fluffy rice buns and hot dumplings for thousands of years. Steam cooking might be an ancient art, but revolutionary technology, a modern regard for putting ingredients first and a drive to lighten up our diets means that the technique is equally relevant today. True innovation combines the heritage of centuries of steam cooking with precision and performance that inspires. “That’s why Gaggenau ovens are all hand finished,” Plumbridge says. “Only when you piece a product together by hand, the good old-fashioned way, are you actually putting soul into a product. And that’s what really means something to people.”

Gaggenau’s factory on the French-German border

Precision Engineering

Darius Sanai takes a rare tour of the Gaggenau factory, pictured above, on the French-German border, and is struck by the melding of industry and creativity

The huge sheet of matte-silver metal looks, somehow, tempting and edible as it sits on the machine bed, like a giant slice of space-age food about to be sliced and diced. Lasers home in on a pattern of points on the sheet, and an instant later, it has a precise latticework of holes and is being washed clean. A few metres away, an operator is in charge of a machine that bends metal. It bends it a tiny bit, almost invisibly, but the bend makes all the difference, our guide explains, as it allows the finished product a smooth, textured finish with no sharp edges.

There is a lot of this in the Gaggenau factory; a lot of working with metal, bending and shaping it, machining it, turning it from sheets, delivered through an entry doorway in one building, into the slick kitchen appliances so beloved by professional chefs.

Yet metalwork was not what I expected when walking into the factory of a manufacturer of the world’s leading kitchens. It’s hard to know exactly what to expect; my experience of factories is confined to manufacturers of cars and watches. Both of these are very obviously made of metal in a way high-end ovens, cloaked in a kitchen design and so proud of their electronics and technology, are not. Yet there is far more metalworking going on at Gaggenau than in, for example, the Mercedes-Benz factory at Sindelfingen an hour’s drive to the east, or the IWC watch manufacture at Schaffhausen an hour’s drive to the south.

Read more: Sassan Behnam-Bakhtiar & the artistic revival of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat

Perhaps this ought not to be surprising. We are after all in a real factory, rather than a mere assembly plant where components made elsewhere are put together. Gaggenau may now be synonymous with expensive homes, but, as a timeline in the visitor experience centre where we had arrived earlier demonstrated, it has a history in metal. It was founded in 1683 as Eisenwerke Gaggenau, an ironworks which made everything from agricultural machinery to road signs, by Margrave Ludwig Wilhelm von Baden. Gaggenau itself is a town in the Black Forest of Germany, which, catalysed by von Baden, became a significant industrial centre and still houses one of the biggest Mercedes-Benz factories.

Gaggenau also made stoves, and eventually specialised in the high-end, highly designed, highly technical kitchen appliances it creates today, eventually moving to its current site from its original home. From the sloping road leading to the current factory in Lipsheim, you can see the curved outline of the Black Forest clearly. “I live there, it takes 30 minutes to cycle in every day,” one of our hosts tells me cheerily. The fact that he lives in Germany and we are just across the border in France’s Alsace is irrelevant: this is the new Europe, and there is, in effect, no border.

It’s a scenic setting for a factory, and also an interesting one: just down the road is Bugatti’s factory (really, a very chic assembly plant), so you could in theory pick up your Chiron and then watch your new steam oven being made. (Actually, the factory tours are not yet open to the public, which makes it even more special.)

The factory is a series of buildings each of which is filled with numerous sections and stations doing different creative activities. Gaggenau’s production process is still very manual; there are 350 workers, many of them trained in astonishingly particular skills pertaining to components or electronics of particular products. There is an air of extreme concentration among the small pods of workers, but unlike in watch manufactures, you don’t get the sense that you are the nth tour to visit that day. Workers are not slickly trained to respond to your questions; some of them are so lost in concentration in operating a particular piece of hot, huge or smelly machinery that they seem surprised to see you there.

What does remind me of a watch factory, or perhaps a pharmaceutical firm, is a ‘clean room’, which we observe from the outside. The room, which sits in a corner of the factory, and the people inside, assembling delicate electrical components of Gaggenau ovens, look like characters in a sci-fi movie of their own.

There is, in another section of the factory, a testing station, where every creation is subject to testing on its accuracy, function, and so on. I lingered a minute or two here, eager to see a malfunctioning multi-thousand-euro oven chucked on a scrapheap (or actually, returned to production to be corrected), but it didn’t happen.

The tour ended and we walked back to the Experience Centre, with its view of the Vosges and walls of the latest steam ovens, slick and architectural, beauty made out of, if not exactly chaos in the factory but certainly industrial creativity. More interesting than any watch manufacture I have been to.

Find out more: gaggenau.com/gb

This article was originally published in the Summer 2020 Issue, out now.

In an age when we are valuing experiences over objects, a cookery class voucher is a welcome gift. Raymond Blanc’s cookery school in Oxfordshire is just across the hall from his bustling kitchen that serves Le Manoir’s restaurant, but the ambience is markedly different. Here is the kitchen of your dreams, fully equipped with state-of-the-art Gaggenau hardware in fine wood cabinets. The school channels Blanc’s culinary DNA through its director,

In an age when we are valuing experiences over objects, a cookery class voucher is a welcome gift. Raymond Blanc’s cookery school in Oxfordshire is just across the hall from his bustling kitchen that serves Le Manoir’s restaurant, but the ambience is markedly different. Here is the kitchen of your dreams, fully equipped with state-of-the-art Gaggenau hardware in fine wood cabinets. The school channels Blanc’s culinary DNA through its director,

Kitty Harris: What is it about coffee that resonates with you?

Kitty Harris: What is it about coffee that resonates with you? would you like to work with?

would you like to work with?

Recent Comments