Aquajenne in Paradise II Elevator Girls (1996) by Miwa Yanagi. Courtesy Deutsche Bank Collection

At the heart of Deutsche Bank’s worldwide art programme is one of the most interesting and diverse corporate contemporary art collections in the world. It is part of the bank’s sponsorship of the Frieze art fairs and instrumental in the bank’s support of this year’s innovative curatorial and philanthropic projects, including a collaboration with London artist Idris Khan. Arsalan Mohammad reports

DEUTSCHE BANK WEALTH MANAGEMENT x LUX

This turbulent year marks not only the 150th anniversary of the founding of Deutsche Bank, but also the 40th birthday of its iconic art collection, one of the most substantial corporate collections of contemporary art in the world. A specialised assortment of works, numbering some 55,000 pieces, the collection spans styles and genres and reflects a global mix of talent, from art megastars to exciting newcomers. The art is predominantly works on paper, as this somewhat neglected medium was considered ripe for collecting and institutionalising when the collection was first initiated by the management board in the late 1970s. The collection is bound by only one other rubric: that the works should provide creative, cultural and intellectual inspiration to the creative, cultural and intellectual inspiration to the bank’s employees, clients, visitors and artists alike.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

The Deutsche Bank Collection, which is part of the bank’s Art, Culture and Sports programme, is based in multiple sites across Germany and in its offices worldwide. It also sits alongside a calendar of art events – the bank is the long-term sponsor of global art fair Frieze, it publishes an acclaimed arts magazine, engages in numerous exhibitions and presentations worldwide, and maintains an active purchase programme that prioritises discovering fresh ideas and idiosyncratic thought from young and older artists around the world. You can witness this for yourself at the bank’s impressive PalaisPopulaire complex, in the heart of downtown Berlin. A purpose-built forum focusing on arts, culture and sports, here one can enjoy works from the permanent collection alongside works on loan, as well as a lively calendar of music, film and cultural happenings.

Molo, Kenya (2008) by Zohra Bensemra. Courtesy Zohra Bensemra/Reuters.

This profound commitment to culture is central to the bank’s ecosystem and is a vital component in its identity. It recalls the pioneering spirit of corporate evolution that began when billionaire philanthropist David Rockefeller began the Chase Manhattan Bank’s art collection back in the 1950s. Since then, the notion of a corporate entity finding inspiration, identity and creativity within art has become standard practice, a means of fulfilling social responsibility, nurturing employees’ potential and attracting clients and business from the world’s wealthiest investors.

The PalaisPopulaire, Berlin. Image by David von Becker

A significant part of this success is due to Deutsche Bank’s Head of Art, curator Friedhelm Hütte, who has managed the collection for more than 25 years. A quiet and learned person, Hütte’s strategy of proactively engaging with, encouraging and supporting new and unexposed talent over the years has given him an appreciation for edgy new art and access to the creative minds behind it. Since beginning at the bank’s cultural division in 1986, he has carefully steered its growth, enriching the bulk of the collection with a knack for spotting talent early. Thus, the bank’s inventory includes early works by Damien Hirst, Gerhard Richter and James Rosenquist, all acquired when the artists were yet to become as famous as they are now. “We always want to discover new artists,” says Hütte, “This doesn’t mean that the artist has to be young – it could be that an artist is older but hasn’t found the success that we feel he or she should have.”

Read more: The market for modern classic Ferraris is hot right now

As well as supporting artists through purchasing work, the bank is also committed to emerging talent via its Artist of the Year prize, which has catapulted artists from around the world at the start of their careers, such as Wangechi Mutu, Yto Barrada, Roman Ondak and Imran Qureshi, into the global limelight. “It’s not simply a prize of a sum of money, it’s really to support the artist, so they can reach a new level,” explains Hütte, who offers the example of how an exhibition by Qureshi led to his being represented by Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris, “one of the top ten best galleries in the world!”

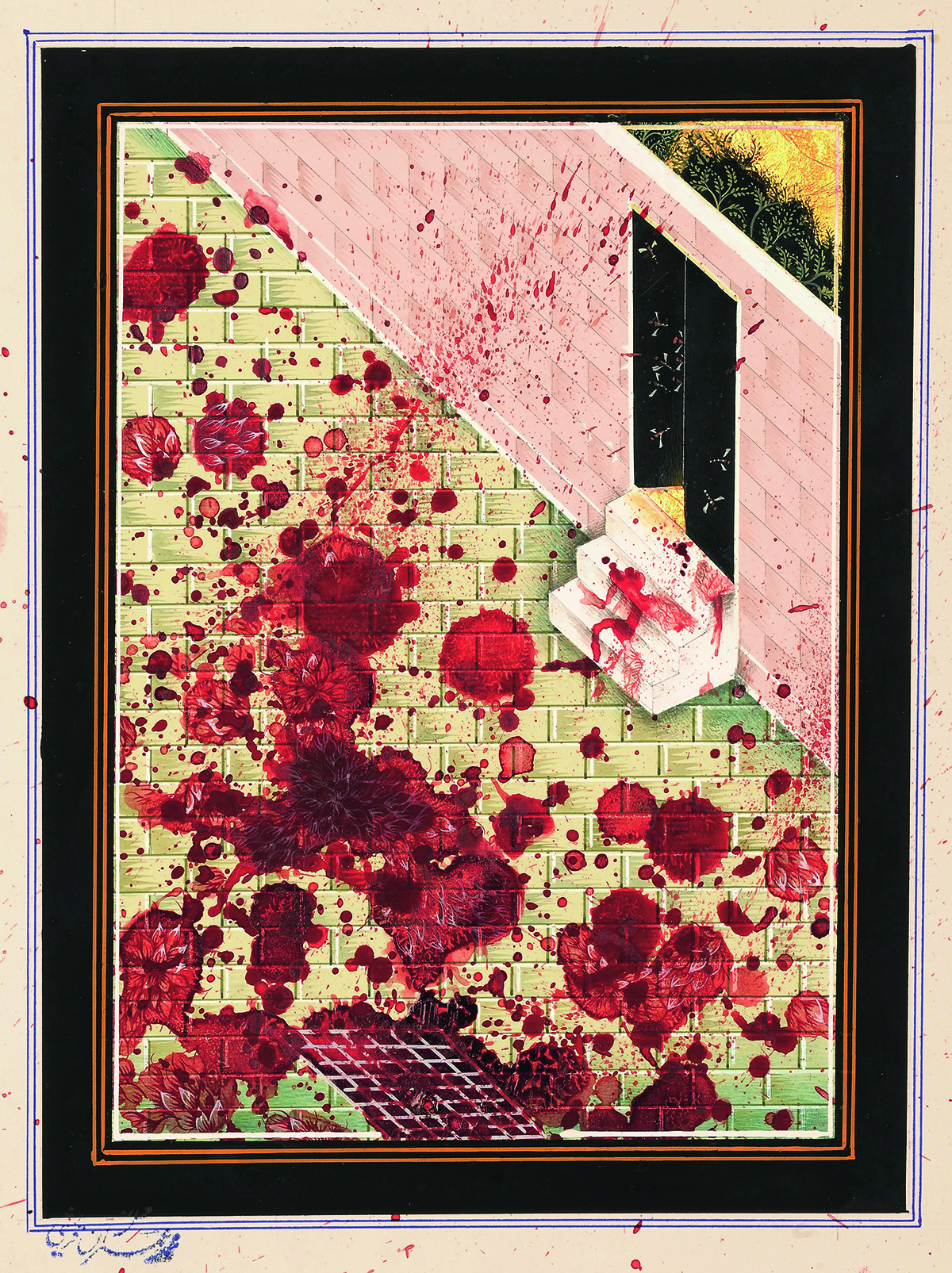

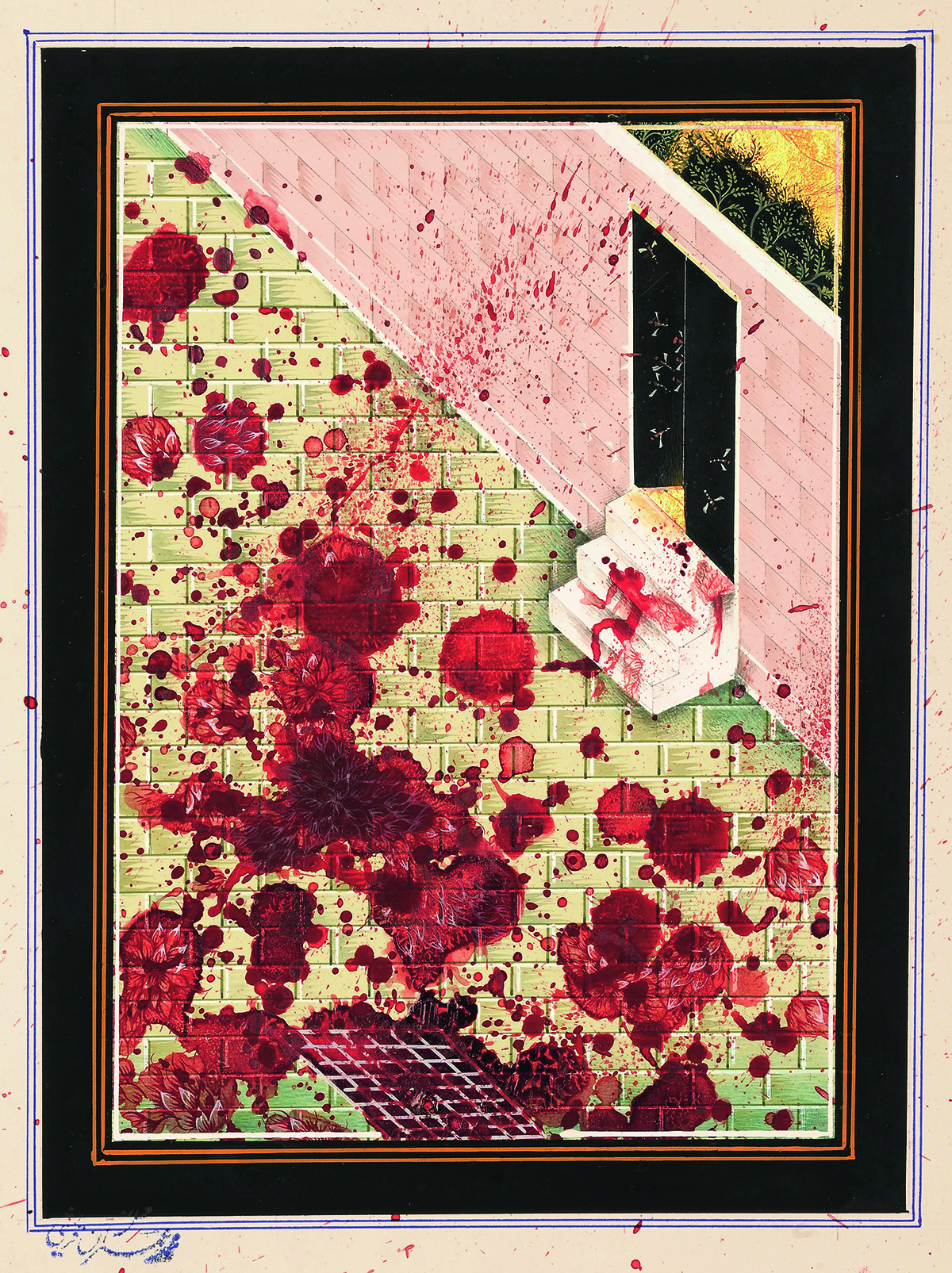

Detail of Blessings Upon the Land of My Love (2011) by Imran Qureshi. Courtesy Deutsche Bank Collection.

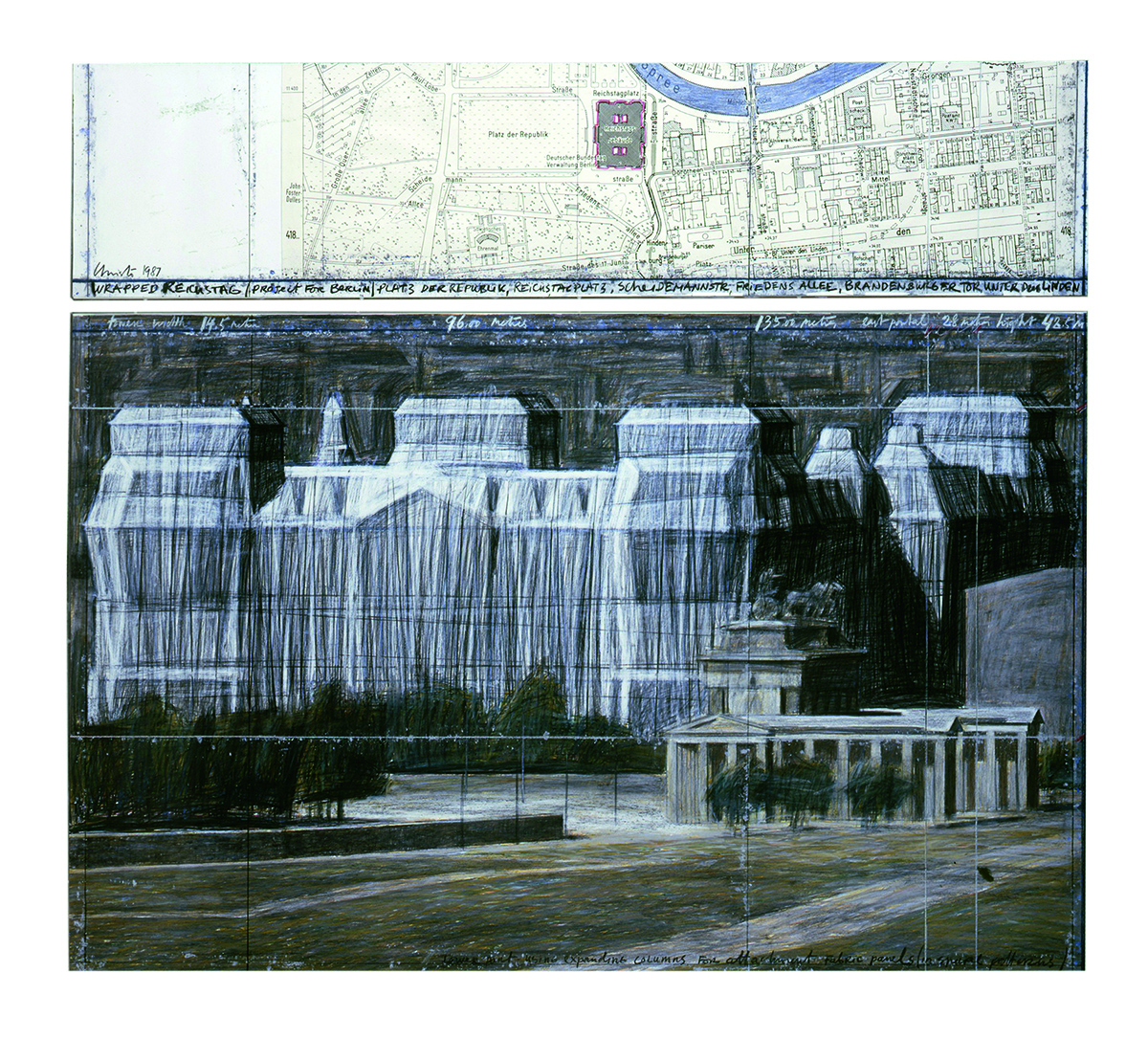

In the summer of 2020, amidst social distancing and other pandemic restrictions, the PalaisPopulaire continued with its planned exhibition of work by artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Christo, who died in May 2020, is best remembered in Berlin for his 1995 performance in which he and his wife Jeanne-Claude wrapped the Reichstag in fabric. The plans, blueprints, ephemera and sketches for that mammoth undertaking have been on show as part of a major exhibition entitled ‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Projects 1963–2020’. The exhibition features approximately seventy works loaned by Berlin collectors Ingrid and Thomas Jochheim, friends of the artist and catalysts for the show.

Wrapped Reichstag (Project for Berlin) (1987) by Christo. © Christo.

“We showed Christo the [PalaisPopulaire] museum last year,” Ingrid Jochheim recalls. “And he was very fond of it. He had partnered on projects with Deutsche Bank several times in the past, always successfully. Just four weeks before his passing, he wrote to me and asked me to give his compliments to the team there.”

But this being 2020, there are more pressing matters at hand. The reconfiguration of partner Frieze London in the autumn as an online event has afforded Deutsche Bank the opportunity to present a curated selection of works that are relevant to our challenging times. The resulting presentation, curated from the collection by the bank’s international art curator Mary Findlay, gathers a selection of more than 30 artists from around the world, each of whom articulate perspectives inspired by issues such as Black Lives Matter, gender equality and sexuality.

Read more: British artist Marc Quinn on history in the making

Titled ‘Taking a Stand: Art & Society’, the online exhibition will show work by a broad spectrum of artists, including Banksy and Joseph Beuys, Iran’s Shirin Aliabadi and Algeria’s Zohra Bensemra, black American artists such as Kandis Williams and Kara Walker, and well-established artists such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Imran Qureshi and Albanian photographer Adrian Paci.

Black Lives Matter protest, Union Square (2014) by Wolfgang Tillmans. Courtesy Deutsche Bank Collection

At times such as these, Deutsche Bank’s fleet-footed operation means their global team have not only been able to respond rapidly and with creativity to events, to build shows on an online platform for Frieze or cope with physical restrictions on visitors to PalaisPopulaire, but also to build on their one-world progressive ethos and take direct immediate action to address the entrenched problem of diversity in the arts.

In association with Frieze, Deutsche Bank are launching a fellowship, The Frieze & Deutsche Bank Emerging Curators Fellowship, to support curators from black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds in the UK. Financing the mentorship and education of a curator is a complex process, but at Deutsche Bank a solution has been found in which one of their prestigious collection artists, Idris Khan, is to design a face mask for sale, based on a design inspired by Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’. The plan is in its final stages of preparation, but the energy and enthusiasm inspired by the chance to make a difference is palpable in conversations between the Frieze and Deutsche Bank staff involved.

Centro di Permanenza temporanea (2007) by Adrian Paci. Courtesy Deutsche Bank Collection.

“The fellowship is about fostering systemic change,” explains Frieze London’s artistic director, Eva Langret, who came up with the idea. “It’s about organisations across the nonprofit and private sectors recognising that diverse programming is not enough, and instead working together to embed more diverse voices within arts institutions and organisations that lead the agenda.” In its first year the fund will be supporting a curatorial fellowship at London’s Chisenhale Gallery and the intention is to inspire an ongoing strategy to empower arts professionals from across communities to make an impact on the country’s art scene.

Read more: Four leading designers on the future of design

Curating change is at the heart of the idea, and at 2020’s Frieze London, we will witness, albeit online, how well this approach fits with the Deutsche Bank Collection. “Where we can, we buy works that make a difference,” says Findlay. “There is this idea about artists using their creative platforms as activism – well, we are buying art to make our offices stand out and look exciting, but in some of those works, we are very much looking at what the artists are trying to articulate. This concept is about us engaging with society and the virtual platform will have all sorts of different types of work. There’s lots of interesting work here. I wish we could put it all on a wall and not online, but there you go!”

While there is every sign that the complex workarounds, compromises and challenges that have come to characterise 2020 will continue into our hazy and uncertain future, in surveying this tapestry of arts from across the globe, we can at least draw solace and wisdom from the world of art to inspire, educate and support our frazzled minds at times of crisis. And with the Deutsche Bank team’s deep-rooted commitment to giving a platform to some of the world’s most urgent and pressing issues, there’s every reason to support and engage with it yourself this autumn.

Idris Khan in his studio. Photograph by Stephen White

Behind the mask

British artist Idris Khan has been asked to make an artwork to help fund the bank’s new fund for emerging curators. Here he talks about his inspiration for the new work.

“During lockdown, my partner Annie and I decided to leave London for the countryside. When we arrived, the trees were bare, everything was brown and black. But over the months, I focused on the changing colours, something I probably wouldn’t have done otherwise. It was almost like watching four seasons within two months!

“I took several copies of Vivaldi’s ‘The Four Seasons’ and decided to paint all those colours that I saw during lockdown.

“The image on the mask is my version of bluebells. First, I watercoloured the sheet music, scanned each page then digitally layered the music on top. It’s like capturing many moments of time of looking intensively and also the time represented in musical notation, so it’s titled Time Past, Time Present. I think that this represents what we’re all going through, hence the reason to wear a mask.

“I think this fund is incredibly vital, as a lot of funding and support has been cut, especially during the pandemic. I believe the fund will give curators the opportunity to make incredible exhibitions and will go on to support diverse exhibitions, so that when this nightmare is over we can all enjoy looking at exceptional art.”

Find out more: db.com/art

This article features in the Autumn Issue, which will be published later this month.

Recent Comments