darvish Fakhr photographed by Hugh Fox

British-Iranian, Canadian-born, American-raised artist darvish Fakhr’s multifaceted practice embraces dualities – light and dark, play and solemnity, movement and stillness – to create a unique sense of tension. Here, Maryam Eisler speaks to the artist about the meaning of his name, cultural heritage and seeking harmony

Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: darvish is a very telling name. Do you abide by the definition of your name?

darvish Fakhr: I never thought about abiding by it, but it was a name that was given to me by my parents, and it has always fascinated me. Growing up, my parents would have Darvish–related items in the house: the axe, and the hats, dolls. I was always curious about it.

[Note: A Darvish is a Sufi aspirant]

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Maryam Eisler: As a child, growing up in the United States, did you know what a Darvish was?

darvish Fakhr: No. I lived on a ranch in Texas with an uncle for about four months. And he said it’s very interesting that your name is darvish “because you have elements of a Darvish in your personality.” I didn’t understand what he was referring to.

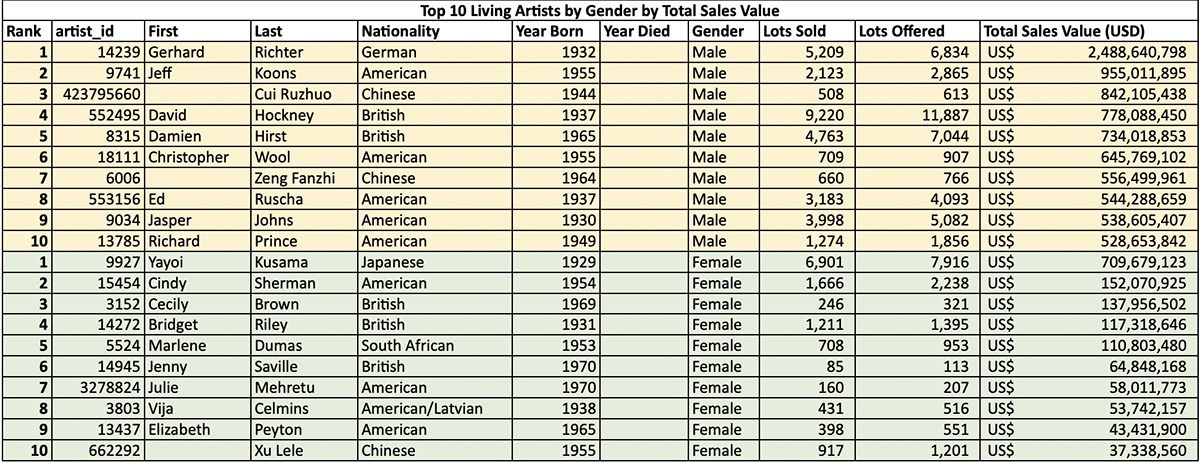

“I gave her an octopus kite for her birthday. It never flew well,” 2020 by darvish Fakhr

Maryam Eisler: What were the personality traits your uncle was referring to?

darvish Fakhr: I don’t know. It was the first time I thought of my name as something other than a name to respond to. Before that, it was just a very unusual name. My American friends hadn’t heard of it. Even for Iranians, it was a surprise that darvish was my first name. I always loved how Iranians pronounced my name, in the way that it was meant to be pronounced, with the emphasis on the ‘e’ sound. I remember liking the sound of it because it had a very hard beginning and a very soft ending, and I felt that I had some of that in me. I’ve always had different gears in my personality.

Above: ‘Notes from the Balcony’ (filmed in Brighton, UK during lockdown)

Maryam Eisler: Do you think this idea of dichotomy in your personality also originates from a cultural dichotomy? You are half Persian, half English. You also spent 27 years of your early and young adult life in Boston, Massachusetts. I also see a multifaceted approach to your art. Whether it is in performance or in painting, you seem to live and be comfortable with these dualities.

darvish Fakhr: The dualities were confusing to me as a child. I never really felt that I belonged to any one thing. And then, because I grew up in Boston, during the 1979 – 1981 hostage crisis, there was a lot of resentment pointed in my direction. And I didn’t understand it. It was very confusing to me. Even my closest friend suddenly flipped on me. Stones were being thrown at my house. My teachers never sided with me either. I felt ostracised those years. And it culminated into a physical explosion which I remember so vividly, surrounded by these taunting kids. I went into this primordial bestial state that became a form of expression. A warning. And it made everyone back off. They had never seen that side of me. It was a very guttural reaction over what was happening to me.

Here and above: darvish Fakhr photographed by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: Was art your answer ?

darvish Fakhr: I needed somehow to come to terms with it, in a way that made sense to me. The only way to do it was through art. Art had a certain alchemy; it offered me the idea that I could take these different elements and turn them into something special. It felt like there was a secret there. And even though I grew up in America, I was fascinated with the Iranian culture. The mystical element of it. My grandmother would pray, and I would watch/be/sit with her. A ceremony in every way.

Read more: Three top gallerists on how the art world is changing

Maryam Eisler: When did you leave Iran?

darvish Fakhr: I never really lived in in Iran. I was born in Canada. And when I turned one, we moved to Boston. I also feel more American that British, even though my mother is English, by origin.

Maryam Eisler: Did you feel that duality in your family nucleus as well?

darvish Fakhr: Yes, my father was an engineer who became a stockbroker, and my mother was a playwright. I always grew up with these extremes in my life. It was the norm. We had a very open minded, somewhat eccentric household growing up. A lot was allowed that might not have been in another household. And I was an only child.

Image by Hugh Fox

Maryam Eisler: At what stage in your life, did you decide to become an ‘artist’?

darvish Fakhr: It came as a result of a slow evolution of ideas, wondering who I was and where I fit in. I started off at Bradford College in Massachusetts and then Boulder Colorado. In Boulder, my mother suggested that I go to Italy for a summer. That’s when I really got into painting, in Tuscany. I then went to the School of Fine Arts in Boston, after which I decided that I wanted to move to Europe, and so I did my masters in London at the Slade.

Maryam Eisler: You personally experienced that antagonistic attitude towards being a ‘foreigner’ as a child all those years ago. Today, thirty or so years on, it would seem like not much has changed as we move towards more polarised societal and political spheres.

darvish Fakhr: It is a worrying state of affairs, but I have hope. I hope that deep down people know what the truth is, but it is the fear that keeps them from embracing the truth, fear of the unknown, fear of change. Deep down, I firmly believe that they know what the right thing is, but there are things that get in the way and muddle up their vision: media, propaganda, fake news. We don’t know what to believe anymore. I also have no doubt that there will be an awakening, but it will happen at a gradual pace. You need to have the darkness in order to see the light, and I am interested in that lightness.

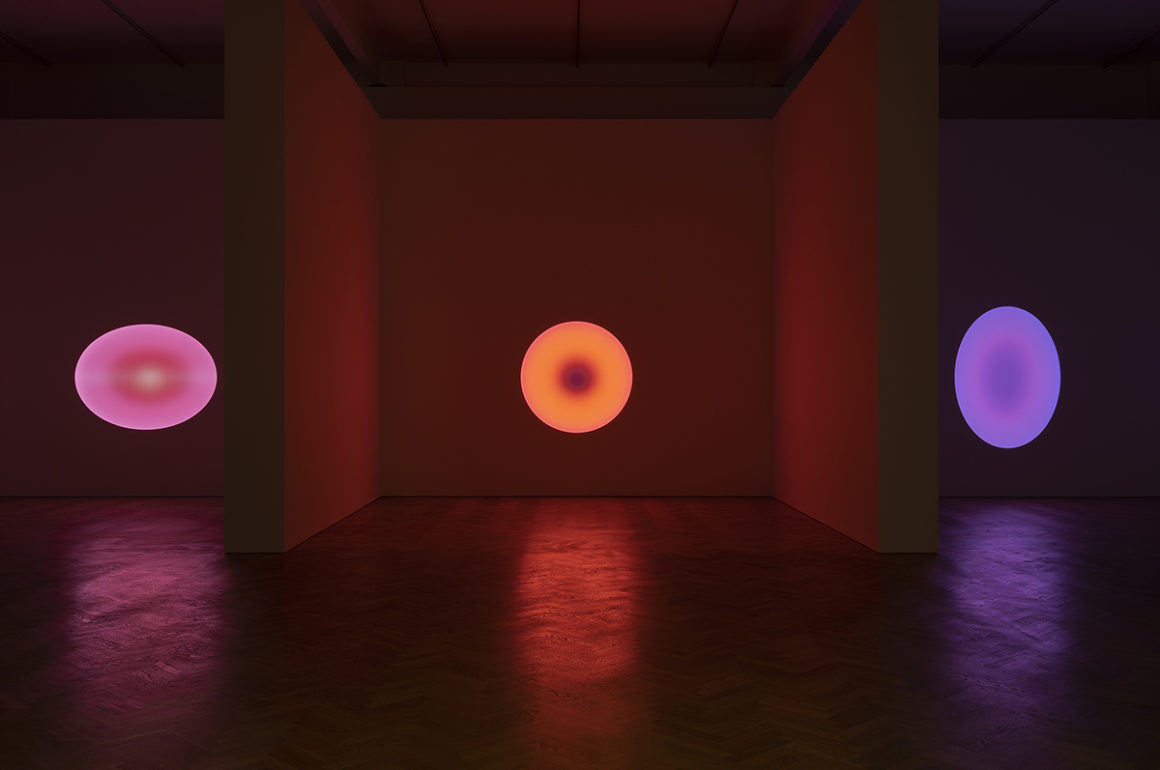

Above: filmed in Venice Beach, Los Angeles

Maryam Eisler: Do you find that ‘ lightness’ in your art? Does your art offer you a sanctuary, a state of calm? Or even a state of possibilities?

darvish Fakhr: I don’t really know where the art begins for me. It just is. Every day. I am more interested in a way of being than making art for a gallery show. I like the idea that there is an overlap. Art, to me, becomes a way of life, a way of believing, a philosophy that manifests itself whether you are painting a picture, or flying on a zip line. And the quality that I am interested in is this lightness, enjoyable and fun.

“He remembers his grandmother mostly for her egg hunts,” 2019 by darvish Fakhr

Maryam Eisler: You paint by memory. Please explain.

darvish Fakhr: That’s right. The lack of information in a memory is what interests me, rather than its high resolution. When I was younger I had a car accident, and I was hit hard on the head. My recording isn’t very good as a result, but I am interested in how I choose to remember things and all the other stuff that’s not included in that memory. Memories are always changing, depending on what your circumstances are in any given moment. It’s this idea of ephemerality in art that interests me. Something that is fleeting, something that is flying through space. Dissipation, or evaporation somehow. Contrasting ideas and concepts.

Maryam Eisler: I also see that in your performances… when you ride the invisible, ephemeral musical wave.

darvish Fakhr: Yes. You can’t control the waves but you can learn how to surf. I like that notion of surfing through your existence. When I do these movements, I often do them in public spaces because I like to feel everything that is around me. And I use that energy to shape what I am working on.

Maryam Eisler: I have noticed your hands shaping the invisible when you perform.

darvish Fakhr: I really feel what is around me. I like to be receptive to it. Some people get the misconception that I am in my own world, but actually, I am very present. I let the music dictate my moves. What I like to do is move in a way that feels natural to me. I also like to do it in public, as I enjoy the stirring up of something that I call ‘gentle civic disruption’. When I am moving, the first thing they want to know is “is he a threat?” When they can see that I am not a threat, then they somehow accept it, or maybe ignore it politely. Or alternatively, they are fascinated by it. Something that is unorthodox. I am okay with all of that. But the notion of surfing is a big part of what I do. I try not to premeditate. Nothing is choreographed. I like to do that with my painting too. What a lot of people don’t realise is that there are a lot of paintings underneath those paintings. I am fascinated by this notion of palimpsest. Where we have stories over stories over stories, but nothing gets suffocated. It is all coming through at some level, and I learned that from Iran, from the walls of Iran.

Read more: Fish&Pips co-founder Holly Chandler on the future of travel

Maryam Eisler: What you are describing to me is human history. Personal stories and bigger histories. Is it not?

darvish Fakhr: Yes. But there was something about Iran that was so ostensible. It was on the walls, and even the road signs were changing. They would bleed through. The community would cover up bits here and there, but the paint would crack and there was something underneath. Something of the past.

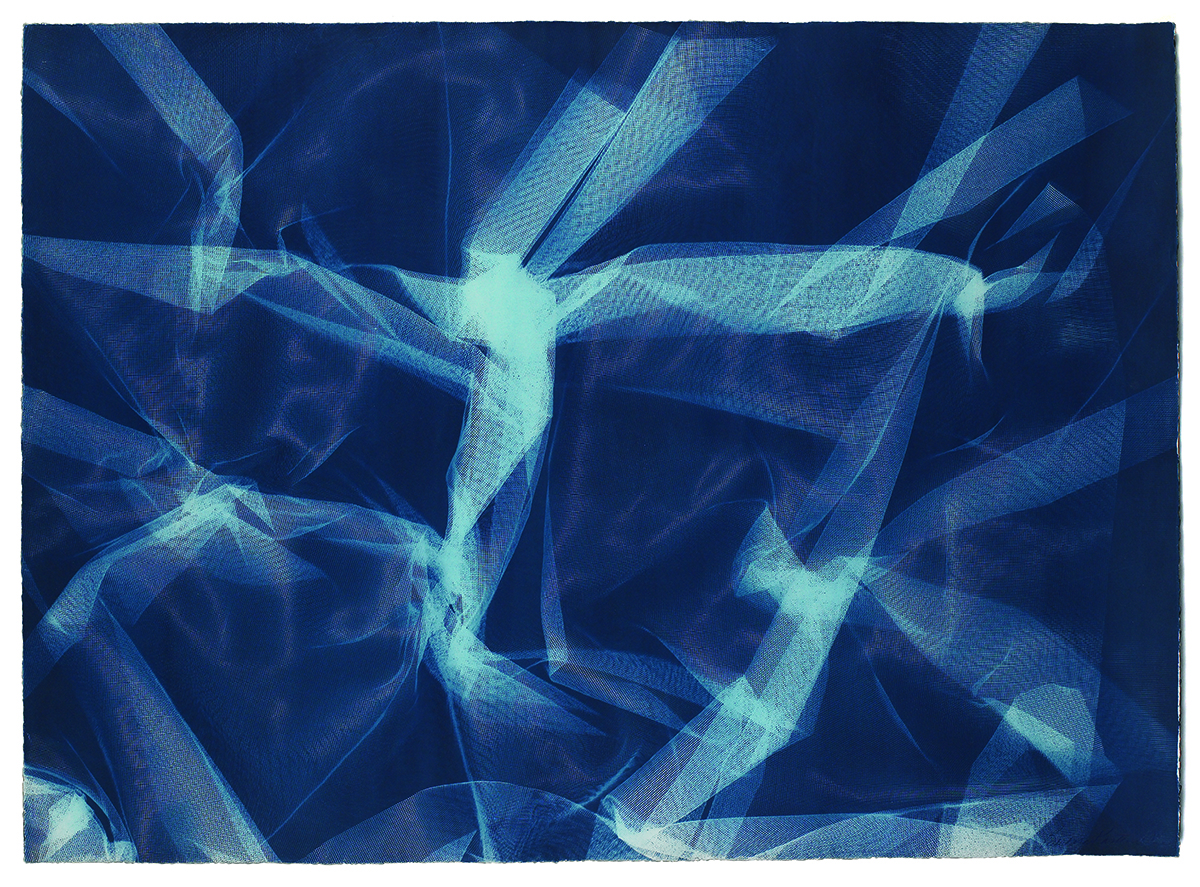

darvish Fakhr is currently collaborating with photographer Hugh Fox on a show entitled ‘Lightness of Being’. Image by Hugh Fox

Maryam Eisler: Where do you find your current inspiration?

darvish Fakhr: At the moment I am excited to be working with photographer Hugh Fox. We are creating a body of work for an upcoming show called Lightness of Being. We hope to show his photographs alongside my paintings along with video and performance pieces. Hugh and I have been working together for about 5 years and when we get together it’s always fun and spontaneous…we just start with a loose idea and then see what happens. The idea could be something as simple as “water” or “corners”.

We do maybe 5% of what the body is capable of doing every day. But, there is so much space there. And the body loves it. I am doing this because I know my body loves it too. And I was starting to break down when I was just painting. I was repeating myself, and I was losing my range of motion. That is when I pulled back. And I stopped painting for a little while. And I have just been working with this notion of fluidity and studying how much is part of who we are as human beings. We are 70% water. We come from water, and then we come into this world. The ageing process is this sort of drying out that happens. I am interested in containing that fluidity and applying it to my art. So that it allows more room for expression. The body ebbs and flows as we inhale and exhale. It is about living it rather than knowing it.

Maryam Eisler: Finally, do you feel that, at this stage of life, consciousness and experience, you now deserve your name?

darvish Fakhr: [laughs] I don’t know. A real ‘Darvish’ goes through a lot of formal training. They study with a master. I wouldn’t say that I can / understand what they understand on that level. I am just doing it my way.

Maryam Eisler: Maybe life has been your master?

darvish Fakhr: That is a nice idea. If it is, then I am still very much a student. My hope is that through my art, the world will see that by borrowing from different cultures, you can create something more special, more unique. I am more about celebrating these differences and combining them into something that can be possibly more harmonious.

Explore darvish Fakhr’s work: darvish.com

Follow on Instagram: @darvish.studio

Recent Comments