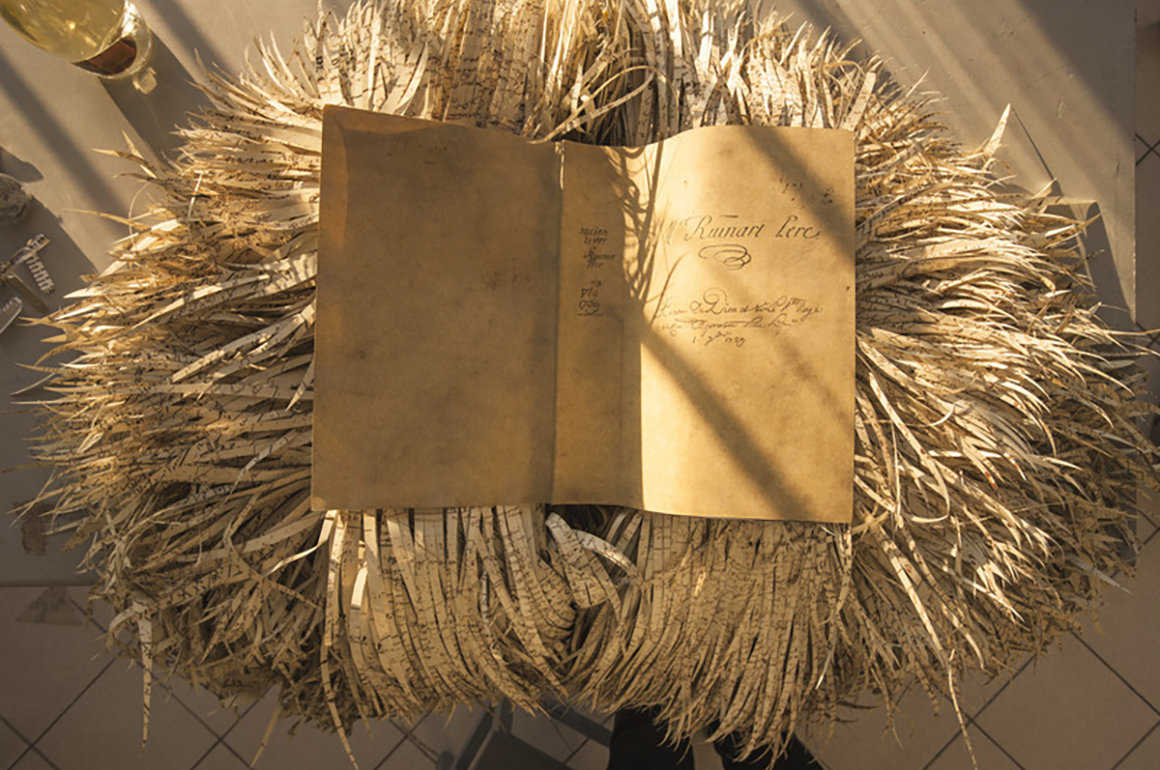

One of the walled gardens at the former Laennec hospital at 40 rue de Sèvres Cour in Paris’s 7th arrondissement, a masterpiece of 17th century architecture that underwent a major refurbishment from 2000 and is now the headquarters of the Kering Group and Balenciaga. Image by Thierry Depagne

Plenty, if you listen to Marie-Claire Daveu. She is in charge of Kering’s 2025 sustainability strategy, the broadest plan of its kind ever created by the fashion and luxury sector. LUX Editor-in-Chief Darius Sanai sat down with her at Kering’s spectacular new offices in Paris to learn more about how Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta et al will become paragons of social responsibility – and why it matters.

“It’s beautiful, and it lets you feel like you can breathe.” Marie-Claire Daveu is looking at a ‘living wall’ on the lower ground floor of her company headquarters; the wall is covered with plant life, a canvas of different shades of green. A few steps behind her, a large space, gently lit, is punctuated by what look at first to be types of dwelling, but turn out to be beautifully sculpted pseudo-retail showrooms. It all feels like the public areas of a boutique hotel, perhaps one carved out of an old chateau.

But we are not in a hotel; we are at Laennec, the headquarters of Kering, luxury and fashion group founded by French industrial titan Francois Pinault and now run by his son, Francois-Henri Pinault. Kering, formerly PPR and before that Gucci Group, owns Gucci, Bottega Veneta, YSL, Brioni, Boucheron, Stella McCartney and numerous other prestigious brands, as well as sportswear maker Puma. [Mr Pinault Sr also owns the auction house Christies and the first growth Bordeaux wine estate Chateau Latour.]

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

But I am not here, at Kering’s new headquarters, to talk fashion. Daveu, as Chief Sustainability Officer, is in charge of the group’s industry-leading sustainability and corporate responsibility ethos, a ground-breaking philosophy that has since its inception in 2012 required each brand to self-impose a rigorous Environmental P&L, which is published publicly, to ascertain how it has complied with the high bars on sustainability, sourcing, carbon footprint, water usage, and other measures stipulated by Daveu.

The philosophy is the brainchild of Pinault Jr, who stated simply that “We have no choice”. Earlier this year, it was expanded into a more comprehensive plan for 2025 which includes a widespread promotion of women within the Kering group and a commitment to reduce the group’s environmental footprint by 40%.

A “live wall” at the Kering Headquarters

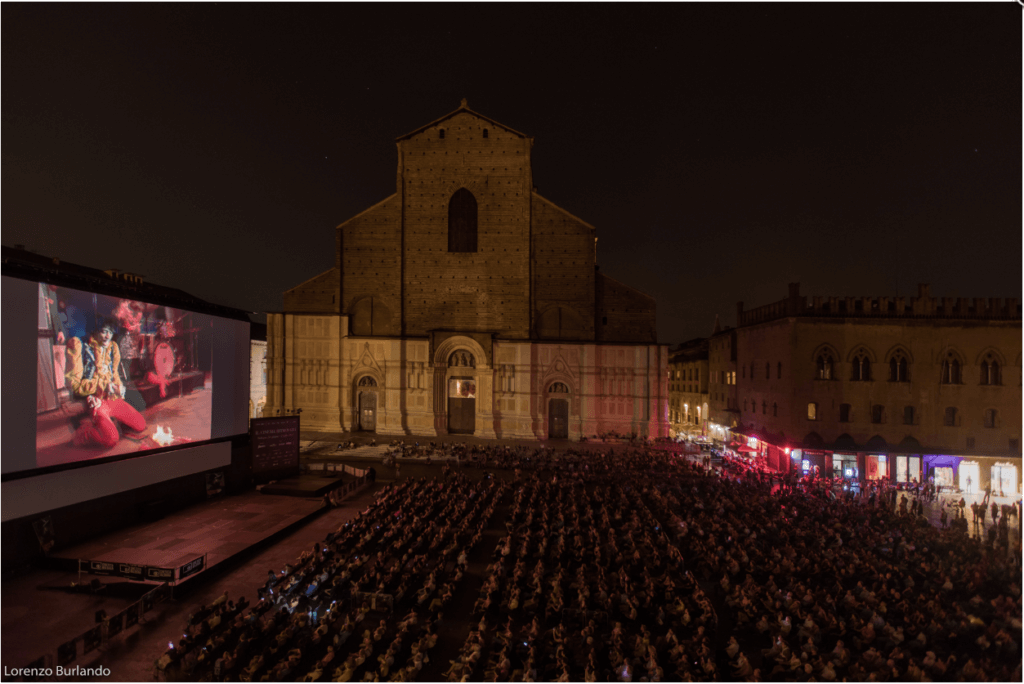

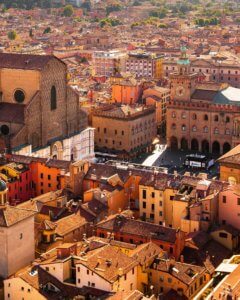

Laennec is the physical embodiment of the Kering philosophy. Formerly a hospital, opened in 1634 and functioning until 2000, it is a palatial building in the heart of the Left Bank. Walk through the gates into the vast courtyard and you could be strolling through the grounds of a chateau in the Loire; there is not a hint of corporate branding, not a suggestion that you are anywhere except within the demise of a beautifully kept stately home (in the centre of Paris!).

This minimal impact on the environment was one of the key concepts behind the company’s move last year.

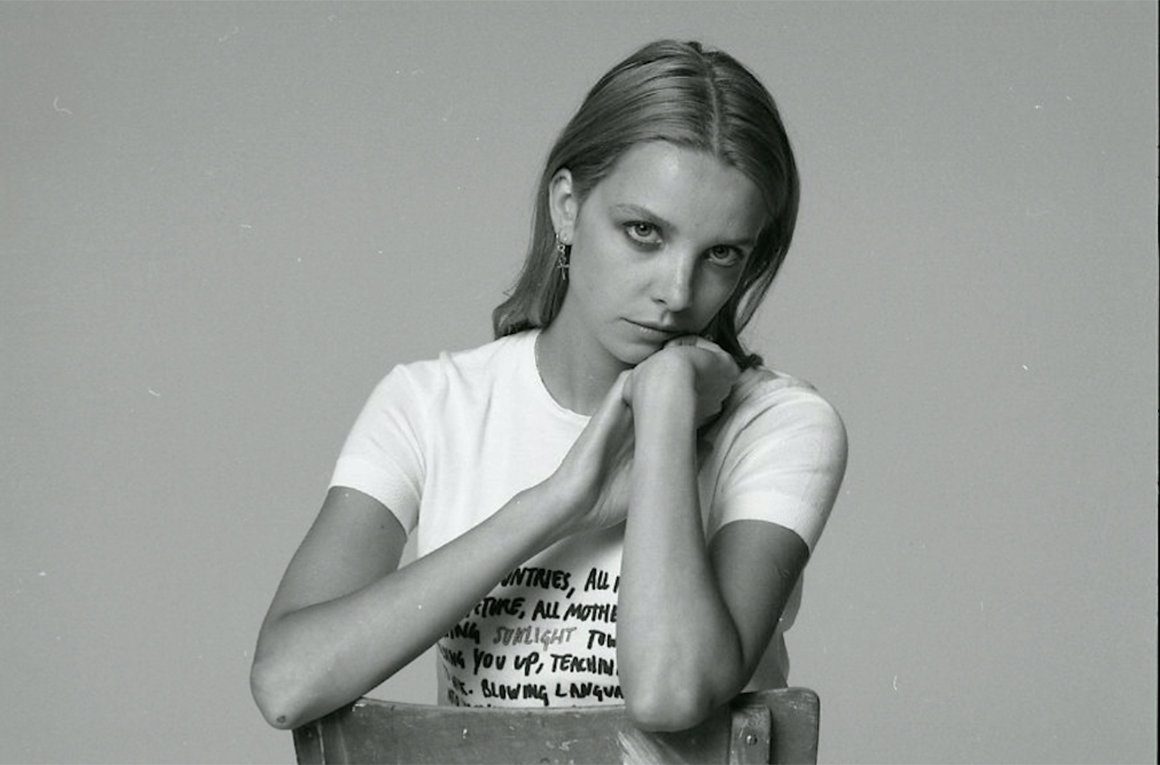

Daveu, slim, chic, and articulate, looks every inch the Kering woman; but she is a conservation academic by training and was most recently the chief of staff within the French Ministry of Ecology. We head along through some more wonderfully welcoming workspaces – the vibe is more hotel-museum-bar than office – into a meeting room. Daveu is enthusiastic, chatty, curious; she takes the copy of LUX I have brought with me and leafs through it, ogling an image of a mountain retreat, wishing she could be there.

She is also candid about the reasons behind Kering’s responsibility strategy and in explaining why individual Kering brands do not necessarily drum the corporate philosophy into their consumers.

Very rarely in the marketing-led world of luxury and fashion does one come across an individual or corporation undergoing a programme, let alone creating an entire corporate strategy, that is not directly aimed at increasing the bottom line in an easily-demonstrable way, whether through sales, PR hits leading to sales, or cost-cutting wrapped in eco-sophistry (like all the hotels who volunteer not to wash your linen for you unless you ask). And yet, Kering’s sustainability and (from 2017) corporate responsibility and equality strategy appear to be precisely that; a philosophy created by an owner aimed simply at raising the bar in luxury and, if not exactly making the world a better place (you couldn’t claim to do that while selling leather bags and shoes and shipping textiles around the world), then limiting and in many cases reversing the harm we are doing to it; as the interview highlights below illustrate.

Marie-Claire Daveu, CSO of Kering. Image by Christopher Sturman

LUX: It has now been more than five years since Kering launched its sustainability strategy. How would you score yourself?

Marie-Claire Daveu: From the beginning, Francois-Henri Pinault defined sustainability as something really key to him. We first defined a set of targets in 2012, for 2016. During the spring of 2016 we communicated externally where we were with every target. That was key to us, because we feel that one of our values, beyond sustainability, is transparency. Transparency not only internally, with our employees, with all of our stakeholders. So that is why we had the feeling that we had not only to communicate the good results, but also when we were not able to reach our targets. And to try and explain why we were not able to reach a target.

So I think it is very important to show that even if you are a major company, you have some difficulties. And it is also through working with other people, people from your own industry, but also universities and NGOs, that you will be able to tackle the issue with and come up with the right solution.

So in a nutshell, we can say, we’ve had major successes. Such as in PVC. One of our targets was to really eliminate PVC from all of our products and we can say we are at 99% PVC free. We were also able to work a lot on our ethics goals because we defined what our ethics goals were. We bought 55 kilos of fair-mined gold. We also have other targets; bovine leather and calf’s leather. The objective was to be sure that they were 100% sustainable. What was very important in this first step was knowing they were 100% sustainable by knowing the traceability. And the first difficulty we found was knowing where it was really coming from. We now have good results for example with crocodiles and alligators – we are over 90% sustainable. Now, when we speak about precious skins we are over 60% sustainable; and this shows that in some areas we have to continue to work on it.

Another development is that now when we make a new hire, they know that they have to be totally involved in the sustainability path. This is also something that creates a real dynamic inside the company. It’s something that is really key. In 2016 we were recognised by external rankings that we still continue to lead our industry in this field.

When we spoke before you mentioned the Materials Innovation Laboratory [a closed location in Italy where the company’s scientists and technicians experiment with new materials]…what I would say is interesting to see is that it has become something very natural for the brand and the design team to cross to the materials from the innovation lab. We need to really push and to create this kind of cross-fertilisation. We say, ‘Go to see them, they are doing interesting things. They can open your mind about new topics.’ So now, we have direct contact between the design teams and the team based in Novara in the Materials Innovation Laboratory. This is one of the key successes of which we can be very proud.

LUX: This year is a key year for Kering – your strategy has moved beyond sustainability and also into human responsibility. Why?

Marie-Claire Daveu: At the end of 2015 we made a major decision that we would like to write a new chapter on sustainability for the next 10 years. That’s why we talked about 2025 [in a media announcement early in 2017]. We made a decision saying we want to continue to define the standards on the social side and on the environmental side. We want to define what we call the sustainable luxury sector or luxury industry, or luxury products. It applies to those three words. We had the feeling with the strength of the work we have done that we can have a 360 degree approach about sustainability.

That’s why this time we decided not only to work with an action plan on the environmental side, but also to include more of the social side. This also links to not only with our own human resources, but to think outside of the boundaries in the supply chain, and also for broader society. As luxury leaders we set the trends, so it was key to work on the social side. We want to also formalise more and to think not only for the short term but the long run too.

One of the most important difficulties I have to manage is that we are in an industry where people, not everyone, are more focused on short term. But when we are speaking about sustainability, we are thinking about the long term. In this company we are very lucky because Francois-Henri Pinault thinks really long term; he doesn’t think short term. But you also have to push inside the company. When you meet some CEOs you speak about the end of the year, that’s okay because it works for the fashion calendar. When you are speaking for the next 10 years, its not obvious for them. Because previously we did not ask them to think in this way. But when you are in sustainability one important learning in our action plan is also the fact that if you want to change things in depth, you have to have time.

You can make incremental progress in the short term, and you have to; but if you are thinking to change a paradigm and change a business model as we want to do, you have to accept that it will take time. 10 years sounds a lot but in reality it is nothing. So you have to think long term, and at the same time to have a calendar accepted by our people also.

LUX: Is it a challenge to get CEOs and other staff to think so long term?

Marie-Claire Daveu: It’s a challenge. So that’s why to tackle this issue we decided to create a specific steering committee for this project. This steering committee was the Kering executive committee. So the first time, at the level of the group, we had the executive group becoming the steering committee of a project; it was to send a strong signal that sustainability is really at the core of our business strategy.

So during 2016 we defined this new strategy. We organised two kinds of road shows. Francois-Henri met the executive committee of every brand to explain why sustainability is key. Also to see how they approached this topic. And he did the same thing with every designer and his or her team. So for the first time we met all the designers and their teams to have an open conversation about sustainability and how they can be more engaged with this field. We have new designers and all of them were very open about this topic. Most of them, not all of them, were really interested.

LUX: Were they interested because they are the younger generation?

Marie-Claire Daveu: Yes. And also when you are a designer you understand the world where you are living. If you don’t understand you won’t be successful. They don’t know the technical side in detail, but they understand that it is not possible to not take into account environmental topics or the social topic, in the supply chain.

After that, where it becomes really interesting is the fact they can express in their manner their expectation, and it’s our job to give them the right tools and opportunities to transform their vision into reality. In our sector the key people are the designer and their team, so if you don’t involve them in the story…okay you will do a great job with the building and the boutiques, but you won’t change the paradigm. During it you can see how much Francois-Henri was involved as he had to see each brand twice every year to explain why sustainability is key. So it was a good exercise for him to wrap up his philosophy and the way we were doing things.

LUX: And do the designers then start to think differently even before they start to design? So instead of thinking let’s use that material for that design they start at the beginning and think what can we design that will be the most sustainable?

Marie-Claire Daveu: We don’t put sustainability as a constraint for the designer or do something that limits their creativity, because at the end of the day they have the last word. But the reaction of most of designers was “oh thinking like that it stimulates us and also our creativity and it gives us another way to think about it”. So for example if we are speaking about fur, they will come and ask their team ‘Could you tell me if this kind of species is okay?’

Courtesy of Kering

And it’s our job from the technical side to identify the suppliers of the cotton farming that will produce organic cotton for example. Cashmere has a major impact on the environmental side because of the land use. So when you look at the EP&L even if you are using a small volume you have a big impact. So it’s very interesting to say look at that, and then after they can make a different choice or we can also say let’s try to find other suppliers in other countries where we will reduce our impact. So it is also how we can create platforms for raw materials. It’s not making the revolution, because when we speak on a lot of topics also with our own experience from the period of 2012 to 2016 I think know we have clearer diagnosis. We have many, many interesting pilot projects. I won’t say we have all of the solutions but we have many solutions. One of the issues of the group is to really put at scale all of the pilot projects we have identified. So that is why also we have both where the designer can come and ask questions and propose them and after it is only to do the roll out of pilot projects.

LUX: Do you personally have conversations, formal and informal, with for instance Tomas Maier [the designer at Bottega Veneta]?

Marie-Claire Daveu: Yes, we began our road show with Thomas Maier, and he for example, during the first period Francois-Henri was also very involved to eliminate and remove PVC for the collection. And they found a way not to use it. But really I don’t want to make a difference between all of the designers because really all of them, I don’t want to speak about Stella, because Stella is also showing the way in the sustainability field, so it’s a little different. But for all of the rest of the designers they were very open and they were very involved in doing something.

To give you a concrete number for the environmental side we want to reduce our environmental footprint by 40%. This is huge. When I say this kind of number perhaps people won’t react and think it’s something huge but it’s nearly half of our environmental footprint. To do that it’s not only in our own operations, but working on the supply chain. If you remember, over 93 per cent of our environmental footprint is linked with the whole supply chain. Seven per cent is linked with our operations only. So if you want to reduce you have to work not only very closely with your suppliers, but also to make a link to find innovative solutions. So that is why to be able to reach this 40% we want to first apply everywhere what we call our ‘Kering Standard Target line’ which means of course to take into account the environmental side, social side and the welfare of animals. One of the topics we want to push during this new chapter is really the criteria for animal welfare. We also feel that as a luxury company we can really push this.

To do all of this, the reduction of the environmental footprint by 40%, we are defining the number for every brand. To be sure that at the end of the day when you add everything up of Gucci, Brioni and Qeelin, for example, that you will reach a reduction of 40% across all of the brands. What we communicate as a strategy is at the level of Kering because as we are Kering what we think is key is to show as a luxury group we can reduce by 40% our environmental footprint. And after, of course, the way of doing it won’t be the same if you are in Stella McCartney or Gucci because you don’t use the same raw materials, you don’t produce the same products and also the design won’t be the same. As concrete example, we can speak about the welfare of pythons, but Stella McCartney doesn’t sue leather or fur so this kind of issue won’t apply to her. Now, if Stella uses new generations of materials she will also analyse their impact on energy because sometimes we have feel we have great ideas and when you do the lifecycle analysis you see its very energy intensive so you have to pay attention.

LUX: Gender parity within your company is also an aim.

Marie-Claire Daveu: At the level of the company we are nearly 60% women but then you have numbers by brands and then by functions. So our objective, like in nature, is to create biodiversity everywhere, at every level and function. So again it is not to apply quotas but it is to take the best but we change the mentality too. It’s an ongoing process. Its 58% women for the groups and then 29% on the executive committee and 64% of directors are women. We are now the board with the most women in the France. We are 64% at the level of the board in France! I can’t tell you how much of a great success it is, because we are a Latin country. Less than Italy but we are a Latin country. Its something new and Francois-Henri wants really to continue to push this. Of course we pay attention to the quality of the people, it’s not to only have women, or international people – if they are not good they are not good. The second goal we have is that we want to be the best place to work in the luxury industry. You can say that that is a little vague so to be sure that it is not only our internal investments we want to use external recognition as we did with sustainability. For example, when you are speaking about climate change you have CDP ranking. So we will try to be recognised externally. The last topic, very linked with business, is that we want to continue and reinforce craftsmanship and specific skills in our industry. It sounds very easy. But we are very conscious we won’t be able to do this by ourselves, even if we have the Bottega Veneta school, the Brioni school, Gucci is working hard with universities but when we are speaking about watches and jewellery we need also to have specific partnerships in Switzerland because we need specific skills but at the same time we won’t hire so many people. It’s something we need to think outside of the box to create something new.

LUX: These new developments, for example the animal welfare, is that all part of your job?

Marie-Claire Daveu: Yes. My job is to find specific certifications, to say to work on in this place in the world not everywhere. When we are speaking about fur, to use not this species but more of this species. So we write guidelines and standards and we give them the tools to reach and apply this standard. This is the work of my team. And after to implement the operations it is the job of the people in the brands. So it is under the responsibility of the CEOs and the designers. We don’t want to only say: “you have to, you have to!” But also to support them. And sometimes, perhaps, we will make big mistakes, so it’s key also to have their feedback and to see what it means. When you are speaking about sustainability we are not NGOs, so we also have to earn money and to be realistic and to be pragmatic.

LUX: Presumably it would be harder to do all of this is the company were not majority-controlled by the Pinault family?

Marie-Claire Daveu: I don’t have that in mind, because we don’t think like that. It’s not a cost, it’s an investment.

LUX: With the end consumer, say the average Gucci consumer for example, are they aware (any more than before) that this is a brand that takes its sustainability and welfare seriously? And does that matter?

Marie-Claire Daveu: I don’t have the quantitative answer; I only hope so. As you know, we don’t communicate directly to our consumer when we speak about sustainability. On this point there are no changes. Perhaps Stella McCartney is communicating a little bit more than before directly with her clients.

LUX: But that was always part of her brand.

Marie-Claire Daveu: But when you buy the product of Stella McCartney it is not written that they are sustainable products. You have, for instance, written organic cotton but if you don’t look for it you won’t see it. And when you enter the shop you don’t know.

Some people think, if they don’t know that about Stella McCartney pieces, they believe that the python skin shoes are real python!

LUX: Maybe only a minority of people are aware. But with Stella it’s one step for the consumer to research, whereas with Bottega or Gucci it’s two steps – “Its Bottega; Bottega is owned by Kering; and Kering has this broad sustainability strategy.”

Marie-Claire Daveu: Gucci, Bottega or YSL, they don’t communicate all of this directly to the customer, true. With brands like Gucci, they are doing some communication at the corporate level. You have Gucci and Global Citizen and Gucci and Chime for Change, but its more focused on the social side. You also have Marco Bizzarri, who has given a few key interviews where he has said a few words on sustainability. But it’s not strong and tough communication, true. As part of Kering they are fully free to communicate or not to communicate. As Kering I think we try to communicate, but I’m sure not enough because it takes lots of time, we communicate more to our industry. As Kering, I am not able to tackle our customers of the brands. But again, our customers are also citizens and they read the newspaper and they look at what happens in NGOs so I am sure they have more information, but, yes it is not obvious. So they have to make the link. Francois-Henri Pinault does not want to put sustainability at the core of the business strategy to sell more products but instead for two reasons. First for ethical reasons and secondly because he thinks there is no other option. It is a necessity if we want to continue our business.

Further, is the fact that I have the feeling that with social media, the new generation ask more questions. They are curious what is behind the products. And when we go to the boutiques and speak to our employees they say that more and more people are asking questions. So it’s good!

LUX: But it’s unusual for a luxury industry to be doing so much and not communicate it via the brands, no?

Marie-Claire Daveu: That’s why we are different. In luxury we are unique. I always say it is the spirit of Francois-Henri that when you are speaking about luxury, sustainability is inherent to the quality. Just as you don’t describe the quality of your product in all of the details. You know its heritage…so it’s a similar approach. You take a care of the people and you take care of the planet.

One thing that is very important in our philosophy is to openly share our discoveries. And to make the link with innovation. We feel that on the social side, but also on the environmental side, that in the next chapter of our strategy we need to push innovation. And to do this we will take two approaches. First is to invest in start-ups and new companies. New companies that can invent new processes or identify new raw materials which could be very interesting. And the other axis is to create more cross fertilisation between our company and other companies. I don’t speak only about digital; it could be with the car industry or the food industry but to create something new.

Courtesy of Kering

LUX: Is that underway already?

Marie-Claire Daveu: No. It’s something want to put in place in our next chapter. And to also work with the technical people in these industries helps to imagine the future. That’s why the supply chain is important. The beginning of the structure is steel forte. It’s really the raw materials because you can have a lot of impact here. Thinking of raw materials that can work across the entire industry. When you are thinking about biodiversity you can think across the industry. I can’t disclose the name but today we are organising a meeting with a few companies which are not in our sector to speak about natural capital. It’s also a way to change the world, to make a better world and also to be very pragmatic. When you are speaking as Kering for many raw materials or processes, even if you are a major company of a big size, we are not big enough to change alone. That’s why we need to go with other sectors that are using the same processes and the same raw materials. And it’s not linked with creativity or the fact that luxury is unique. You have to divide. You have the “back office” and after you have creation – creation is key. But we have a lot of work to do on the basic things. You asked me about the customers…a lot of people ask this question. I think to be honest it will take time. For me, they don’t ask questions because they think the luxury world is already perfect. This is why we are continuing with this strategy and connected with the London College of Fashion. We feel that training is important but in fact it is very operational because we anticipate a need to prepare the next generation of people who will work in the fashion world. For us it is time and investment. We don’t have a direct feedback about money but we feel that it is our responsibility. If they have this way of thinking during their studies, when they take responsibility in brands it won’t be a question for them. It will be something they put into reality very quickly. We developed our app with Parsons in the United States called “My EP&L” for the students. We simplified the EP&L a lot but it’s to show the environmental cost of each of the materials and processes involved in the student’s design. For example, which material, from where, to manufacture where and then you get the result of your environmental footprint. Behind every item we have a way to calculate each of its environmental impact. After, what is very pedagogical is that you can change silk to cotton instead and you will see you will reduce your footprint by only changing one thing you can make a big difference. For students this is great fun.

LUX: In terms of the specific stories where we are talking about production and the sourcing, in terms of your suppliers, are there any stories about how suppliers have changed or you have chosen suppliers who have changed their ways so it has benefitted both the environmental, the humanitarian and social side?

Marie-Claire Daveu: It’s a tough question to answer. What we have done and what we are doing with some suppliers is to apply a program which we call “clean by design”. It’s more focused on the environmental side which I why I’m not answering for the social side. What is interesting to think is that first, these suppliers are not only working for us, so when we apply this program it is to create a specific relationship with the supplier and we hope that it will also be useful for their own business. They can present to other customers the fact that they take into account the environmental side, energy and water consumption etc. So I will say one very big major program we have is suppliers in Italy and we want to develop this program outside of Europe for example, in China. We also have a specific program linked with embroidery in India. I don’t know if you know how it embroidery factories work in India but its men, because this kind of work is not done by women. You have a different kind of structure and now all the luxury companies are going to their embroidery to India because you have this kind of skill there. So we are trying to develop a specific program with these kind of suppliers not only to improve the working conditions of the employees but also to give them a vision and support them in developing their business in the future. Also to pay attention to the fact it is noble to work in this field to continue so the next generation are inspired too. We have to work more and we want to go beyond social compliance and work on capacity building. That’s for the next chapter. When you are talking about social compliance it’s less sexy as a story. But its hard work we have implemented in 2016 we have work to continue to put sustainability clauses in our contracts. To put in place a specific team to do audits in our supply chain. We create this new entity at the level of the group, at the corporate level, the report of the internal audit. We create the structure, the process to be sure. And this takes time as we also need to explain to our suppliers why this is key. Not only to have control, we are not policemen, but it is a win-win effect for them. When we meet problems we won’t say we won’t work with you but it’s to help support them implement the right solution.

LUX: And these suppliers are presumably long term suppliers? Because they are going to change their structures to work with you?

Marie-Claire Daveu: I wouldn’t say it like that. Most of our suppliers in the luxury side we know them very because we have been working with them for a long time. When they make these changes in investment and practice it’s not only for us. The world is changing. So if they want to develop their business in they need to develop their sectors to include sustainable criteria. One of the key elements we want to share with them is that it is not just to please us but it is also a self-investment. Of course the size is not the same because when you are in luxury its small suppliers, kind of atelier, you don’t have so many people. But they need our support and the support of other big groups to help them. This takes time. My opinion is that it takes time because you have this small structure. When we change suppliers, for example if we have a new designer and he wants a new kind of fabric, and you need to identify a new supplier, we are doing pre audits. The contracts, the clauses, the support. So it is really a partnership with the suppliers in this field. After explaining to them how important this is and they are interested in this it’s good for them. But at the beginning they only see it as a constraint. It takes time, you need money and you have to accept it will take time to explain everything.

LUX: And then it has a much bigger effect on the industry.

Marie-Claire Daveu: Yes, you have a kind of snow ball effect.

LUX: Fast fashion and disposable fashion are very un-environmentally friendly. Is that a challenge? Or does it not affect you because it’s not your part of the industry?

Marie-Claire Daveu: I would say as Kering we have our vision, and we implement it, after that I hope we can influence others. To set standards in our sector, we can help and support change. We are all in the textile sector – and we are the second most polluting sector. So as a sector we really have to include into sustainability or we won’t be able to continue. As Kering we try do the best we can within our own boundaries and we try after to influence our suppliers and to show others that it is possible to include sustainability. Which is why it comes back to the designers and the universities because if you raise awareness about this kind of topic to new generations who will work in our industry…not all will work in the luxury industry but in the textile industry it is good to spread sustainability everywhere.

Interiors of the Kering Headquarters

LUX: Tell us about this sustainable HQ building. Were you personally involved?

Marie-Claire Daveu: Yes. We are the first building in France, with this kind of certification, both the BREEAM and HQE. When you are building for the first time, creating a new building, it is easier than in our case, when you have to manage with an old monument or a pre-existing building. This was more complicated because you have to respect the culture and the history and at the same time add to it. We are the first historical building to have the BREEAM certificate. You can’t just do what you want. You have to respect the culture of the building which I think is important, but of course also it costs more. And if you don’t want to spend more and more money, you have to be innovative and to find a way to be environmentally friendly and to keep the culture of the place. Step one was the building and step two is how you manage the building. We are involved in both because we feel the number of kilowatts a business can lower is huge.

We are also going to make honey in our garden with our own bees. This summer, certain people will be receiving a small quantity of honey from Kering – it will be so luxury. Très très chic.

kering.com

Recent Comments