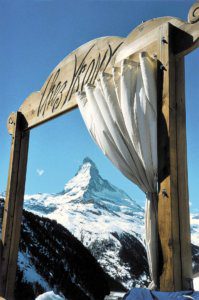

The breathtaking views of the Matterhorn are worthy of any postcard and a million selfies

Above Zermatt, Switzerland’s most spectacular mountain village and home to the Matterhorn, high-altitude restaurants like Chez Vrony combine tradition with chic, and put the haute into cuisine, as Darius Sanai discovers

All-round views are breathtaking

Mountain hut cuisine will be familiar to anyone who has skied the Alps; raclettes, fondues and other dairy confections. Fresh in the best sense of the word – sourced locally, recently – but rarely sophisticated.

We were looking forward to a little mountain cuisine as we approached Chez Vrony, in Findeln, high above the resort of Zermatt. It was a clear, warm summer’s day, and we had been hiking down from Fluhalp, a hut positioned high above a former glacier I enjoyed gazing at in my childhood in the 1980s (now melted, due to global warming, Mr Trump). The hike had taken us through a fantastical rock wonderland – where part of the mountainside above had simply collapsed into several football fields of Mini-sized boulders. We strode along the side of Stellisee, a lake whose reflections of the famous Matterhorn, facing us from across the broad Zermatt valley, have featured in a million postcards. We edged along a narrow path, a sheer drop to our left, as the glacial valley disappeared into a stream far beneath us; we could just make out the sound of a stream, a distant, constant swirl, like a giantess shushing its infant.

Read next:Kazakh artists make world art breakthrough at Venice Biennale

Descending, we walked past the highest trees, stumpy starter Christmas trees that had the temerity to grow above the otherwise uniform treeline; and skirted around another lake, this one more green, where children splashed and a thousand tiny frogs appeared and vanished into the grass on its edge.

The restaurant’s idyllic terrace, above the Findelnbach stream

Past a rock ridge, we gazed down and saw the hamlet of Findeln, home to Chez Vrony; only another ten minutes of descent down the well-made, sand-covered path and we were there. Chez Vrony is a wooden village hut from the outside, a sophisticated terrace restaurant from the other side. Ushered in by a lady who knew everyone (was this Vrony? Her daughter?), we were whisked past groups of well-dressed hikers (a curiosity in itself) and sat on sheepskins atop benches by a broad wooden table. The Matterhorn stared down, a world of ice, rock and snow, across a forest and a valley. We could have been served supermarket sandwiches and would have declared it the most wondrous refuge in the world.

But Vrony has other ideas. The menu was haute cuisine in both meanings: ingredients plainly sourced from the mountains, like the ‘pink-roasted entrecôte of Swiss lamb served with a port-steeped fig and hazelnut potato purée’, but with real panache and delicacy. (For a simpler option, the beef in the Vrony burger was sourced from the pasture above the hut.) We could have stayed all afternoon; indeed I think we did.

Vrony serves mountain cuisine with a sophisticated touch

Afterwards, it was 45 minutes’ rapid downhill hike through a scented forest as dusk approached, to the outskirts of Zermatt. The Matterhorn, changing angle and mood, always there with us, always a reminder that, however civilised the food, and however much we melt the glaciers, above Zermatt, this greatest of all Alpine villages, is a wild world, not our own.