Portrait photograph by Melanie Dunea

Marina Abramović has been tortured and almost killed, by her own audiences, for the sake of her art. She has also redefined the genre and democratised it. The world’s most celebrated performance artist, whose works span five decades, speaks to Darius Sanai ahead of a major retrospective at London’s Royal Academy

In The Marina Abramović Method, a board game-style card set recently issued by the world’s most celebrated performance artist, you are told to spend an hour writing your first name, without pen leaving paper; walk backwards with a mirror for up to three hours; open and close a door repeatedly for three hours; and explore a space, blindfolded and wearing noise-cancelling headphones, for an hour. Some of the instructions, given on large, Monopoly-style cards, are more onerous: swim in a freezing body of water; move in slow motion for two hours. But none of them come anywhere close to asking users to inflict on themselves the suffering and danger Abramović has put herself under over five decades of pushing the boundaries of art.

As she explains below, the Method was intended to take its users away from their phones, and put people in contact with themselves, inspired by her own journey, over 50 years, to understand her own body and mind. Purchasers of the card set can be grateful that Abramović does not suggest they train to become her. The New York-based artist has been lacerated, tortured, cut, stabbed, asphyxiated, rendered unconscious, and more, in the name of her art. She first came to public consciousness in the 1970s with performances like ‘Rhythm0’, in Naples, when she stood in a studio for six hours, provided the audience with implements including a scalpel, scissors, a whip and a loaded gun, absolved them of responsibility, and told them to do what they wished. She did not flinch as she was assaulted, cut, and manipulated.

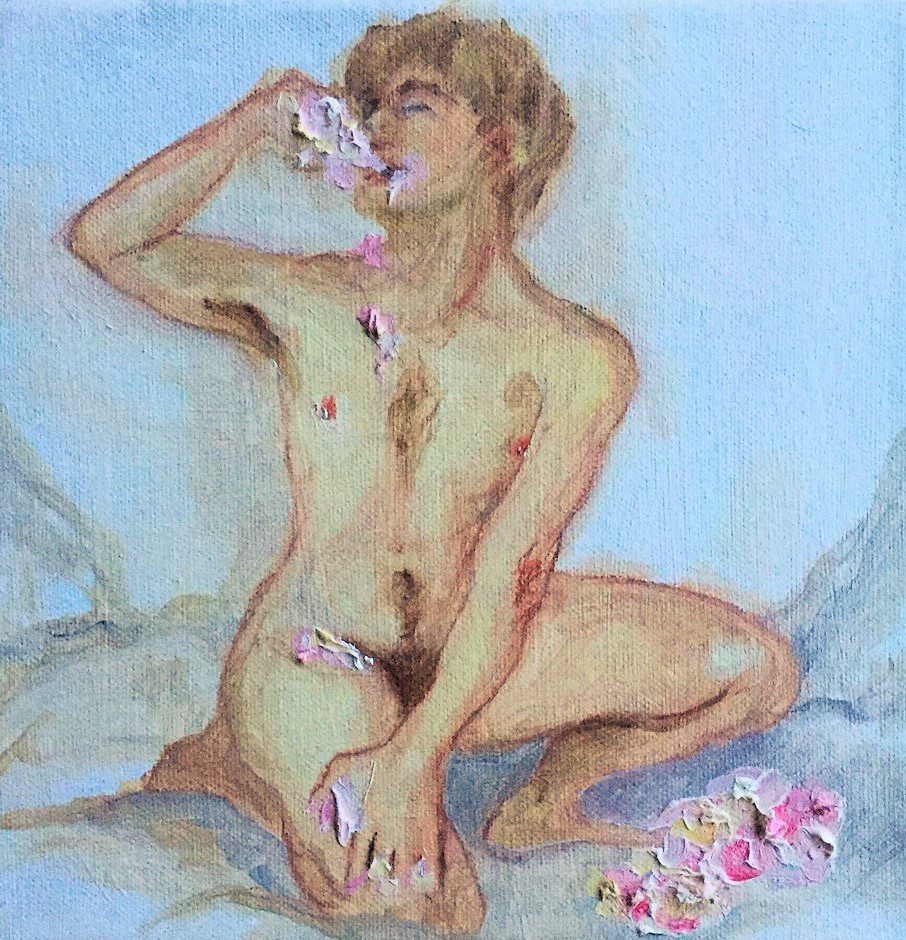

Marina Abramović in a scene from her performance ‘7 Deaths of Maria Callas’, in 2019

Other performances in the same era saw her render herself unconscious; in 1997 she spent four days scrubbing bloody, rotten cow bones in a performance of protest against the war in former Yugoslavia. Possibly her most celebrated performance, ‘The Artist is Present’, which remains the most significant performance artwork in the history of New York’s MoMA, she spent a total of 736 hours sitting static in the museum’s atrium while visitors lined up to take it in turns to sit opposite her (among those who did: Lou Reed, Björk and James Franco).

So, what would Marina Abramović the person, rather than the silent artist, be like? Catching up with her ahead of a major exhibition spanning her life’s work at London’s Royal Academy of Arts (dates to be announced), I was prepared to interact with someone as brutal and scarred as she has a right to be, but was surprised to find a pleasant, highly articulate, methodical, thoughtful, quick-witted and humble interlocutor. Her thoughts on cancel culture and the effects of social media on creativity are as sharp as the scalpels she once offered the public to cut her with. Her answers are art in themselves.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: I have been playing around with The Marina Abramović Method: Instruction Cards to Reboot your Life.

Marina Abramović: The Abramović method came from my long search for how to train myself as a performance artist to be able to really understand my body and mind. For that, I went to different cultures, I went to deserts, to Tibet, to shamans – lots of places to work in different retreats and to try different techniques. This is really dedicated not so much to artists or performance artists, but to everybody. Everyone – farmers, soldiers, politicians, factory workers, young children – can do this method. The exercises are very simple, which I think is beneficial, and it puts you in contact with yourself. I also liked the idea of creating cards, so they’re playful. You have that playfulness, like in a game: you close your eyes and pick a card up and do the method. This exercise is my effort to go back to simplicity, away from technology and video games, away from all this presumption that takes you away from your own intuition.

Marina Abramović cutting crystals whilst exploring Brazil in 1992

LUX: Your performance over the years has involved a lot of danger, personal suffering, and challenges to yourself.

Marina Abramović: In my cards, there is no suffering, no bleeding, none of this stuff. I am not responsible for anyone else, only myself. To me, one of the biggest human fears is the fear of pain. It’s interesting to me that if I stage painful experiences in front of an audience, when I go through this experience to get rid of the fear of pain, and I show that it’s possible, I can be inspirational for anybody else. It doesn’t mean people have to cut themselves or do dangerous stuff, but to understand at the same time that pain does not have to be an obstacle. You have to understand what it is and how to deal with it in your own life. If you look at rituals in different cultures, every initiation conquers the moment of pain, and it really strengthens the body and mind. If you’re afraid of something, don’t sit there and do nothing about it, go through it and have this experience. That is the only way you can be transformed, getting out of your comfort zone.

LUX: Are you trying to change the audience through your performances?

Marina Abramović: The only way that I can get all this attention and understand what I’m doing is to show courage and ability at the same time – that I’m vulnerable, but I also have the guts to do it. Two things. An artist should be inspirational to other people. They have to have a message, to ask questions, not always to have an answer. The pain, the suffering, the fear of dying: these are all elements not just of contemporary and classic art, but the history of humanity.

LUX: Were you always very brave as a child?

Marina Abramović: I was. It was not an easy childhood, to start with. I had a very strict, military upbringing. I was also very sick as a child. I suffered from a condition that caused long durational bleeding, a bit like haemophilia but different, so if I had a tooth taken out, for example, I would have to be in bed for three months sleeping so as not to choke from the blood, because it wouldn’t stop. I had lots of obstacles. Being raised under Communism contributed as well – Communism is all about being a warrior, not caring about your personal life, and sacrificing your life for something. When I came to the West, everybody looked so spoilt to me.

Marina Abramović in a scene from her performance ‘7 Deaths of Maria Callas’, in 2019

LUX: Does it affect the depth of what modern Western artists can create if they haven’t suffered or seen difficulty?

Marina Abramović: The young generation has a whole different set of problems than I had. Their problem is a feeling of being kind of lost and melancholy, of apathy and a lack of belief. You can’t generalise, and of course there will always be one Mozart in every generation, someone who starts creating art at the age of seven. But the others have a lethargic way of life. Everything is available to them. They don’t need to fight for anything. Computer, video games, ice cream: whatever they want, they have it. When I was growing up, I was allowed ice cream once a month if I was good, and mostly I was not. All of this is different. So, I always see them as spoilt, but at the same time it doesn’t come from them, but rather their parents. It’s complicated. I think it’s important now, the idea of the Forest School learning model. They have it in England. Kids can come to the forest and make their own fires, to find food, to learn simple survival techniques. I think it’s a way of going back to simplicity. Simplicity is the way to survive.

Read more: Sophie Neuendorf’s Inside Guide To The Venice Biennale

LUX: Before, in the 1980s and 1990s, people were either creators and artists or they were audience. Now, everyone is a creator. Does that devalue real art?

Marina Abramović: Some years ago, I was invited to go to Silicon Valley to talk to tech people about art, and to my incredible surprise, I found out that they seriously believed that Instagram is art. That was so surprising to me. Instagram is, to me, a very personal way of seeing the world and sharing it with other people. It’s a tool for communication. It’s so far away from art. Art is so different. Also, now, with NFTs and all this new technology, all anyone is talking about is how much it costs and the amount of money that can be made. It has quickly become a commodity. But I really don’t see content, real profound ideas that can move me and bring me emotions, and I think that’s what art is about. [Digital media] unifies people and breaks the borders between countries and individuals, but this is not art. I’m sorry, but it’s not art.

LUX: Has there been a fundamental change in art since the 1970s or 1980s?

Marina Abramović: It is so different. The needs of society are different. In the 1970s, there was so much experimentation. There was incredible freedom in the art scene. Now, we are facing political correctness and diminished creativity in so many ways. So much art that we were doing in the 1970s would never be possible now, because it would be so scrutinised and criticised that galleries and museums would not show it. This is something that, unfortunately, does not help creativity right now.

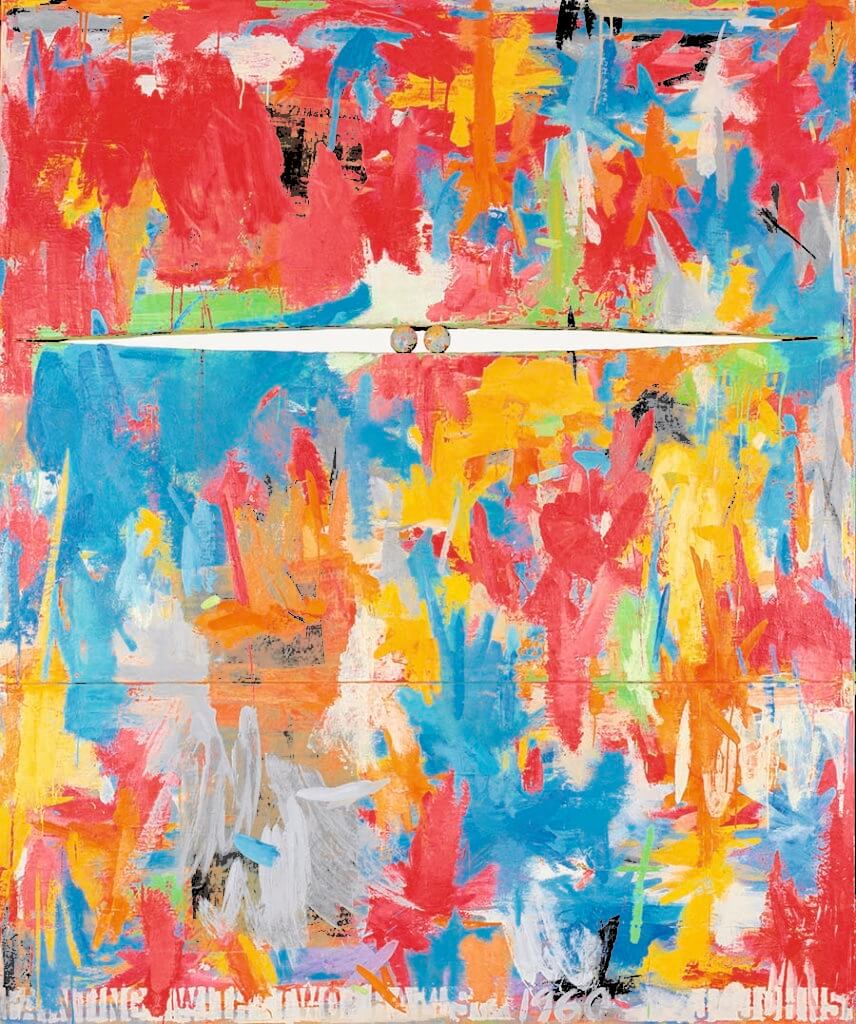

Portrait photograph by Melanie Dunea

LUX: Are people stopping themselves from creating because of political correctness?

Marina Abramović: The true artist does not care about this shit. They don’t care. They will always find a way to do things, if not publicly then it could be underground. Historically, that has always happened. Artists cannot stop creating. It’s an urge, like breathing. You can’t question it. You wake up with ideas and have to realise them. This is your oxygen.

LUX: Do you think the West – what we used to call the ‘free world’ – is going to have a movement of underground artists because they can’t express themselves publicly?

Marina Abramović: I really think so, yes.

LUX: You are taking over the Royal Academy in London. What will we see there?

Marina Abramović: The Royal Academy is, for me, a very big obligation – an honour. I care so much about this show right now, because it’s showing what makes my 50-year career. There will be some really important major artworks from each part of my career of 50 years, but also there will be a big amount of new work, which nobody will have ever seen before. There will be a reperformance element, with young artists reperforming my early works, which I introduced some years ago. Some of my contemporaries say a performance cannot be reperformed – I disagree. And then I am also preparing my new work, which I can’t talk about because I’m superstitious, but I’m definitely doing a personal performance. The show is called ‘Afterlife’. I like this very ironical title, because I’m still alive. I have waited a longtime for this show, because it was supposed to be in 2020 but then Covid came, so it was postponed for three years. You know, at my age, three years is a long time, so I’m really looking forward to the fact that finally it will happen.

Marina Abramović in a cave whilst exploring Brazil in 1992

LUX: If you had been brought up now, in America, compared to when you were brought up in what was then Yugoslavia, would you still be the same artist?

Marina Abramović: I don’t know. I was very happy where I was brought up. At that time, I read all the books that Americans don’t. Not all of them, of course, but generally Americans don’t read. I was very happy with my education. It was so intense. Full of poetry and art and everything.

LUX: Do you still put yourself in as much danger and physical stress as 20 years ago?

Marina Abramović: I have to say, ‘The Artist is Present’ was a hell of a performance and I was 65, my dear. I could never do this when I was 20, or 30. I didn’t have the willpower, wisdom and determination. There was no way. I needed time in order to have the strength. You get strength when you get older and not younger.

Read more: LUX Art Diary: Exhibitions to see in May

LUX: Do you fear getting older?

Marina Abramović: Not so much now – sometimes, when I wake up on a rainy day with pain in my ankles and shoulders, but not generally.

LUX: Do you fear anything?

Marina Abramović: Of course, I fear. Everyone fears things. I have a childhood fear, that if I go to the deep sea, a shark will come and eat me. Even if I go to the ocean and they tell me there aren’t sharks there, I know that the shark knows I’m there and is going to come for me. But that is an old fear from childhood. Like everybody else, when I go on a plane and there is turbulence, I’m immediately writing my testament. I fear. But I think it’s natural, it’s living, you’re living, you’re alive. You’re not immune to fear. Nobody is.

This article appears in the Summer 2022 issue of LUX

Recent Comments