After the unexpected success of his first two books, Amish Tripathi resigned from his career in financial services and became a full-time writer of spiritual fiction. Twelve years on, he has sold 5.5 million copies across 9 books and achieved the records of fastest- and second-fastest-selling book series in Indian publishing history. The polymath has since added more strings to his bow as a fledgling film producer and Director of London’s Nehru Centre, which promotes cultural exchange between India and the UK. Tripathi speaks to LUX about his life philosophy and the future of Indian culture on the global stage

1. Your first book, The Immortals of Meluha, was rejected by 20 publishers before you self-published it, and yet it went on to become a bestseller in India within its first week of sale. To what do you owe your persistence?

Ancient Indian wisdom says that the most persistent and effective are those who are detached from success or failure, because failure fills demotivation in your heart, which can stop you, and success fills pride in your mind, which can distract you. If you can detach yourself from consequences, and just enjoy your work, your karma, then you become unstoppable.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Perhaps, without realising it, I was following this ancient Indian wisdom from the Bhagvad Gita. I was happy in my financial services career. I was earning well. So, I wasn’t really thinking too deeply about whether my book Immortals of Meluha, would succeed or fail. I wasn’t seeing it as a way to make money, let alone a pathway to another sustainable career option. The book was, in a way, the voice of my soul. And I just wanted to try everything that I could to get it to readers. After that, it was up to the readers whether they liked it or not.

I still follow this philosophy of detachment when I write. I genuinely don’t care at all about the opinions of readers, critics, editors etc when I write. I write the way it comes to me, trying to be as close to my heart as I can. That’s the best way, I think, for any creative to be. Be detached, true to the art, and don’t think about success or failure. The rest is up to fate.

2. You started writing full-time – resigning from your 14-year career in financial services – following the success of your second book, Secret of the Nagas. What prompted that change from banker to author of spiritual fiction?

By that time, my royalty cheque had become more than my salary. So, it was a pragmatic, albeit apparently boring decision. I know it sounds sexy to get a great idea, kick your boss, and jump into something new, but I had to be pragmatic and practical with my career choices. I come from a humble family background; I cannot be irresponsible. There are always bills to pay!

3. Your books tend to amplify the historical. What role do you think the past plays in informing the present?

There are two approaches to change in human civilisation. One is evolutionary, where the present builds upon the shoulders of the past, taking along the best of the past, while reforming that which is not good. The other is nihilistic, where it is assumed that everything about the past is bad, we need to break it all down, and start from scratch. I am certainly not nihilistic: I am evolutionary in my approach.

That doesn’t mean that I think we should oppose all change, where we worship traditions to the extreme and become hidebound; but the other extreme of being nihilistic is not good either, since it usually leads to too much chaos. The evolutionary path, where we retain the best of the old, and bring in the best of the new, is, in my opinion, the best way. And I guess that reflects in my writing.

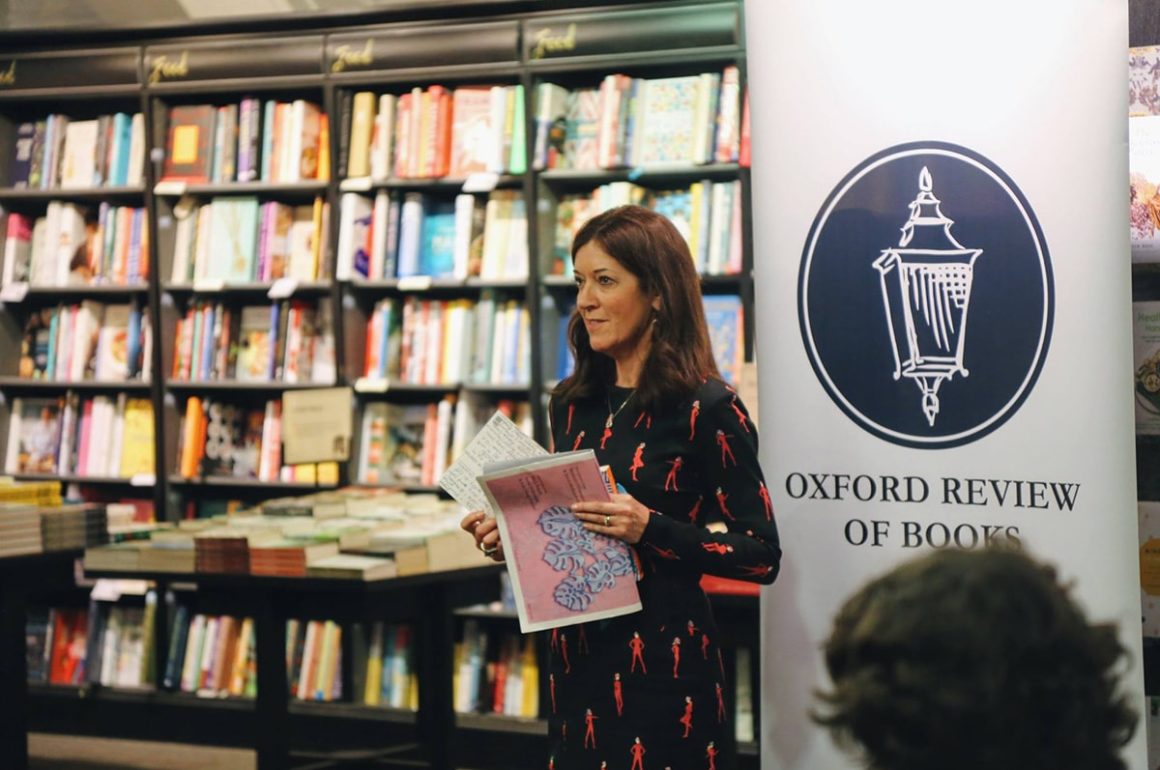

Amish Tripathi speaking at an event with Anil Agarwal and Amitabh Shah

4. Your next project will see you produce the film adaptation of your book, Legend of Suheldev: The King Who Saved India. How are you preparing for that challenge?

I have been an author for over a decade. And the Gods have been kind to me in this field. But film production is a completely new area for me, and when one is entering a new area, it’s always wise to get good partners. This project is also period war film, so the budget is quite significant: we need to manage it well. We have hired senior people in my production company, Immortal Studios, based in Mumbai. We have also tied up with a TV production company (one of the largest in India) as a partner for this project. I am hopeful that we will be able to put together a good film on King Suheldev. We will certainly try our best!

Read more: Emilie Pastor & Sybille Rochat on Nurturing Artistic Talent

5. Besides being an author and columnist, you’re the director of the Nehru Centre, London, which works to facilitate intercultural dialogue between India and the UK. Why is it important for you to engage in diplomatic work of this kind?

I genuinely believe that ancient Indian culture has particular relevance today. We are told about a dichotomy nowadays: namely, that one can either be traditional or liberal; one cannot be both. There are problems with this approach. If we destroy all traditions, sense of family and community, then we atomise society. We end up with the problems of loneliness and the mental health and stress issues that naturally result. At the same time, if we put all traditions on a pedestal, then we have no space for liberal ideas like women’s rights, LGBTQ rights etc. Society would be in a far worse situation without these liberal ideas.

Ancient Indian culture can provide a model for that balance, of being both traditional and liberal at the same time. This gives you the roots and solidity that traditions give you, but also the freedom and ability to soar that liberalism provides. Isn’t that worth propagating? This is what I get to do through this diplomatic role, and it’s why I enjoy this job – because it is in consonance with the values I try to imbibe into my writing.

6. Are you optimistic about the future of Indian art and academia on the global stage?

Certainly. I think ancient Indian culture always had something positive to contribute to the world. But since for most of our post-independence existence, India was an economic under-performer, with very little global power, it was understandable that few foreigners were interested in our culture. Despite those constraints, however, many parts of our culture have been accepted across the world, including yoga, Buddhism, cuisine, films, and so forth. As our economic footprint expands and India becomes a wealthier and more influential country, I am sure that more and more aspects of our culture will find salience across the world. I am proud that through my diplomatic role and my books, I get to make my own small contribution to this journey.

Recent Comments