-

-

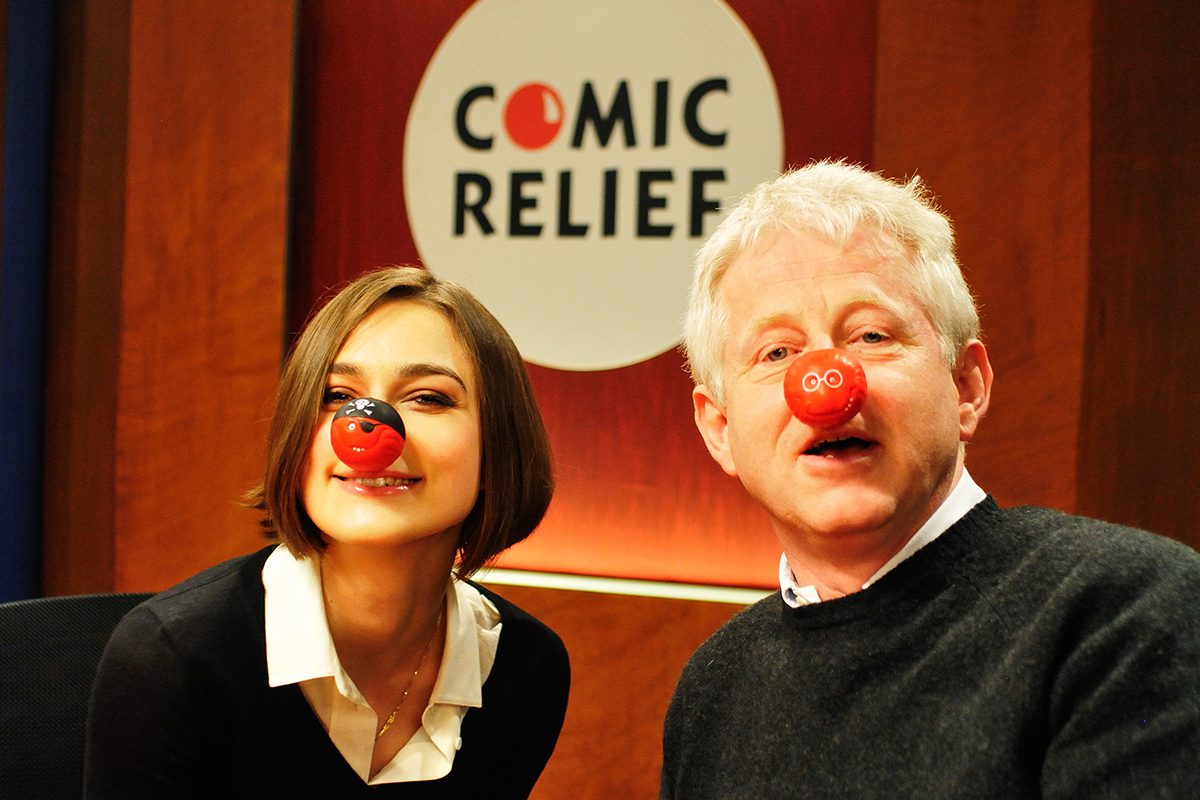

Freida Pinto – The actress shot to international fame with Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

-

-

Abhay Deol in Raanjhanaa

-

-

Superstar Sonam Kapoor

-

-

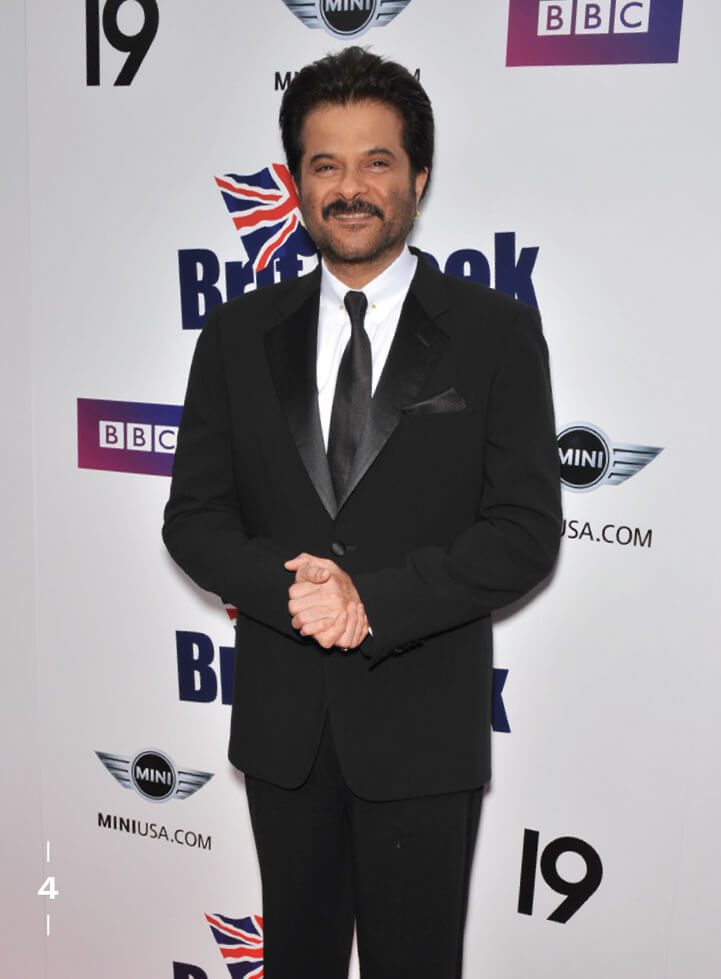

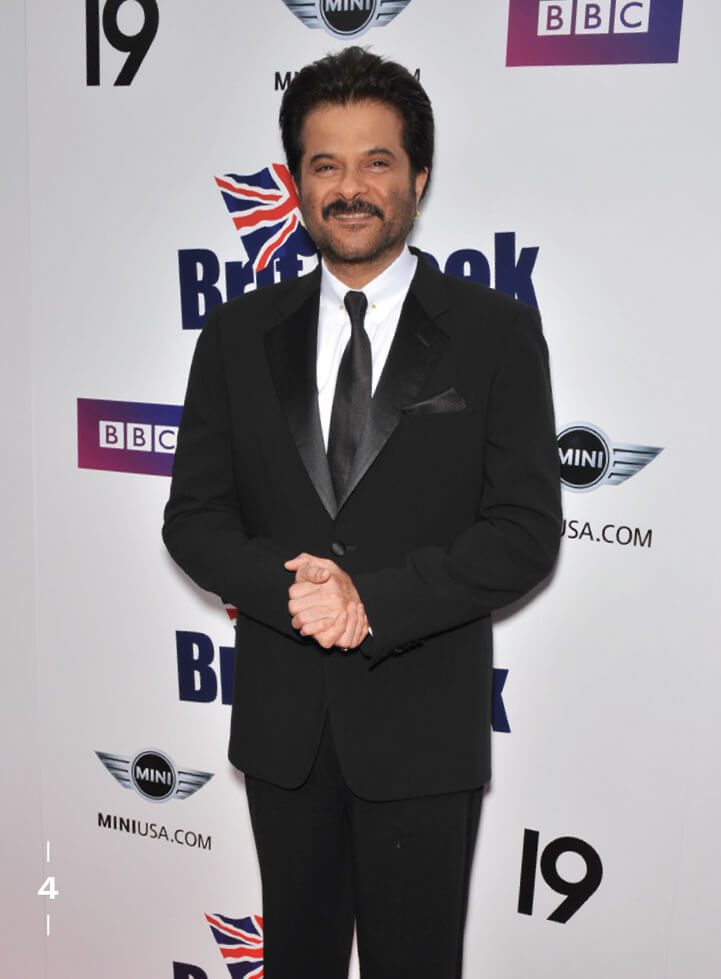

Anil Kapoor – The acclaimed actor appeared in Slumdog Millionaire for which he won a SAG Award

-

-

Raanjhanaa, one of 2013’s Indian blockbusters by Eros International

While Hollywood stagnates, Bollywood is thriving. CAROLINE DAVIES charts the exciting progression of an Indian film industry that is going global

In India, cinema is more than just weekend entertainment. Producing roughly 1,000 films a year, the industry is projected to be worth US$4.5 billion by 2016. Its stars are filtering into LA; Amitabh Bachchan appeared in The Great Gatsby, Irrfan Khan as the baddie in The Amazing Spider-Man and Priyanka Chopra, or rather her voice, appeared in Disney animation Planes. Other names and faces are also seeping into the international consciousness: Aamir Khan, Anil Kapoor, Freida Pinto and Aishwarya Rai Bachchan are but a few. Hollywood may still have the lion’s share of the global film market, but Indian film makers are snapping at their heels. Slumdog Millionaire, Laagan and most recently, Three Idiots, the highest grossing Bollywood film to date, drew big audiences at home and abroad, and with it, new international investors.

But Bollywood is more than a business. It has, after all, been bringing a sub-continent together for decades. Its all-singing, all-dancing and mostly Hindi language films captivate billions, watched everywhere from rural village screens erected on cricket pitches to massive urban cinemas crammed with city workers on a Friday night – not to mention among expatriates the world over. In India, the songs are hummed in fruit markets and blasted out in nightclubs.

Bollywood is taking risks. The stars, the structure, the stories and even the songs are starting to stray from the tried and tested formula of the past. This is a brave new India and it is demanding more.

“Eight or 10 years ago we thought that cinemas would close down,” says Rakesh Roshan, a Bollywood actor, director and producer. “They were very bad; the sound system, the seating, the toilets.”

“The upper middle class had stopped going to the cinema. They watched films on DVD,” says director and composer Vishal Bhardwaj. “Until the multiplexes arrived.”

India’s huge economic growth over the past decade has nurtured the middle and upper middle classes, predominantly based in the major cities. In the early 2000s, multiplex cinemas sprang up in the urban hubs of India. Unlike the pre-existing single screen cinema audiences, the new, airconditioned, well-maintained complexes offered multiple smaller screens.

“Previously, if you couldn’t make a film that filled a hall of 1,000, then it wouldn’t get made,” says writer and director Sriram Raghavan. “But multiplex screens have 200 seats. People will come and fill that.”

The audience packing out these smaller screens does not necessarily have the same taste as the masses in the halls.

“I think cinema audiences have matured,” says Vikas Gulati, a film and music director. “They are looking at films with a little more meaning. They have seen international ideas and storylines.”

But director and producer, Rohan Sippy begs to differ. “I think that audience was always there. They were always open to good content,” he says. “But still, certain types of film are still not going to have more than a 30 million audience, which is pretty small when you consider the population density.”

Thirty million may be a small percentage, but it is still a sizable demographic. Targeting different audiences has given film makers a new freedom to experiment.

“Indian cinema used to be split into commercial and art house,” says Bhardwaj. “Art house was dying, almost dead. Before, being ‘art house cinema’ meant that no one would watch your film. Since then the line has been blurred.”

As concepts have developed, songs have been squeezed. “Every film used to have eight songs,” says Roshan. “Then it came down to six, then five, now three. Now you have songs playing in the background without lip sync. Now people have less time so we have to make shorter films.”

“Songs used to be patches in the narrative,” says Bhardwaj. “Seventeen years back, if the song was not good, people used to go out and smoke. That doesn’t happen now, because directors are trying to incorporate it in the narrative.”

A new generation might also not have as much need for a musical interlude to help the story along. “In Hollywood, they express love by having an intimate scene,” says Roshan. “Because of the sensitivities, we used to have a song. All that can be explained in Hollywood in 30 seconds, we have to show in five minutes. Now the censors are becoming more liberal and we can convey it in a shorter way too.”

But songs are in no danger of disappearing altogether. “When they are badly done, they are a detour,” says Dr Rajinder Dudrah, Bollywood academic and Head of Drama at Manchester University. “But Bollywood song and dance sequences are crucial. When done well they act as narrative accelerators. If you cut out a particular song you would miss a crucial element of the plot.”

“It is the way the audience has been conditioned for more than 100 years,” says Bhardwaj. “There is a song for every occasion in our life and every region has their own in a different language. Marriage, coming of age, death; when we laugh we sing, when we cry we sing, so it becomes a part of our culture.”

It is also a part of the commercial culture. “Songs in Bollywood music are a very big promotional tool,” says Gulati. “It gives you free play on music channels. From the producer’s point of view it makes a lot of sense, because you play a video for three minutes for free rather than for a 30-second advert.”

“I think that the need for songs in Bollywood films is slightly a self-fulfilling prophesy,” says Sippy. “Conventional wisdom says you need a song and the films don’t get made or promoted without, therefore you don’t know how to do without the song. It seems unlikely to completely change; music is still a big reason why people come into movies.”

-

-

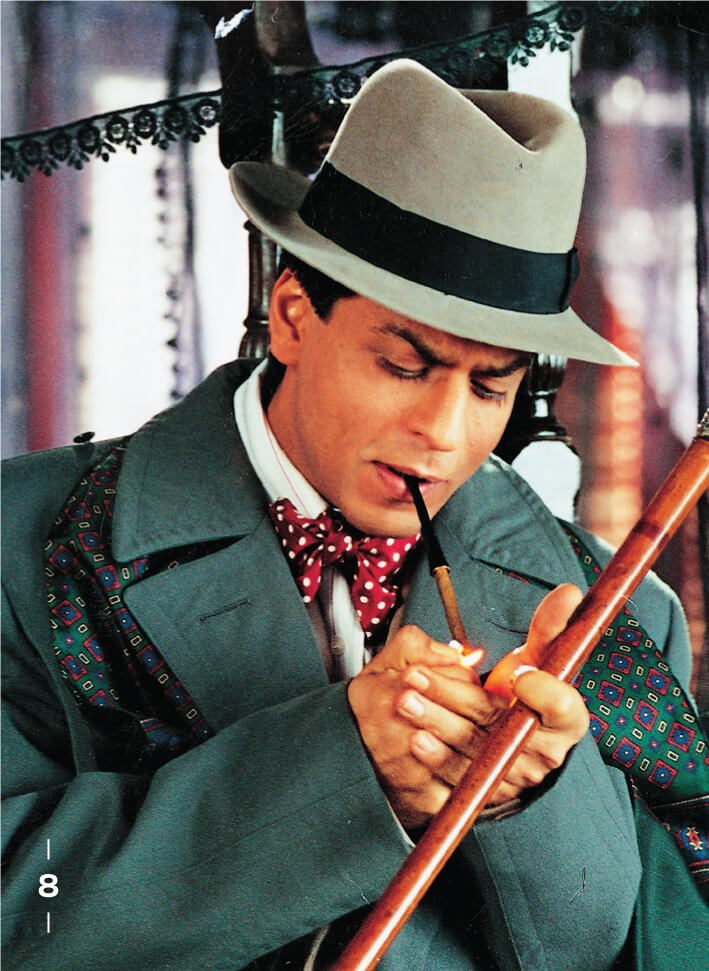

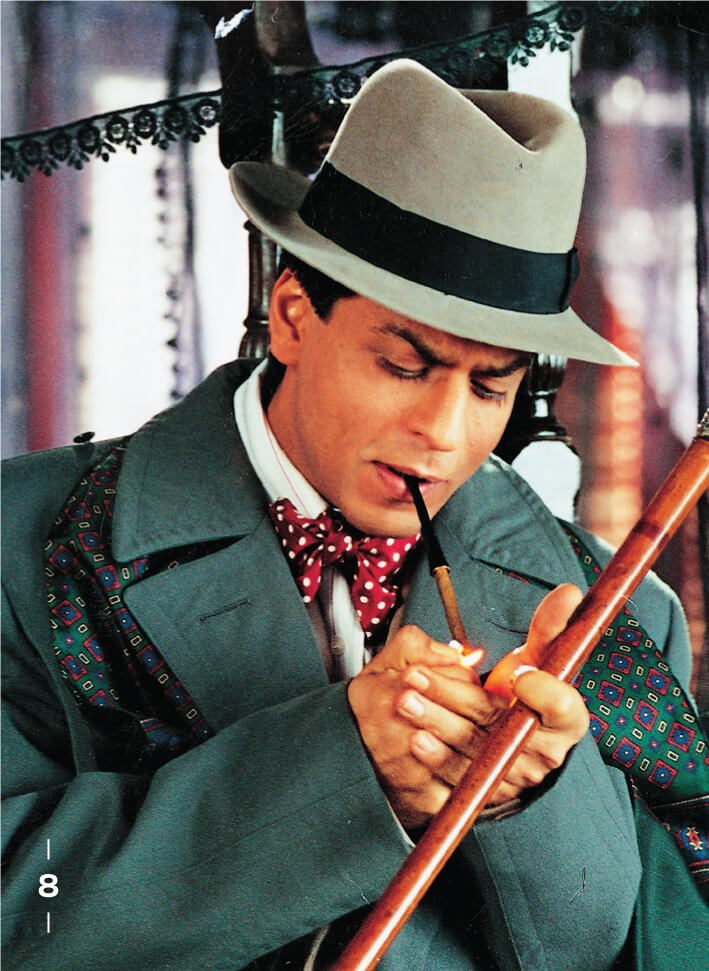

Bollywood megastar Shahrukh Khan

-

-

Jackie Shroff with Shahrukh Khan in the 2002 romantic drama Devdas

-

-

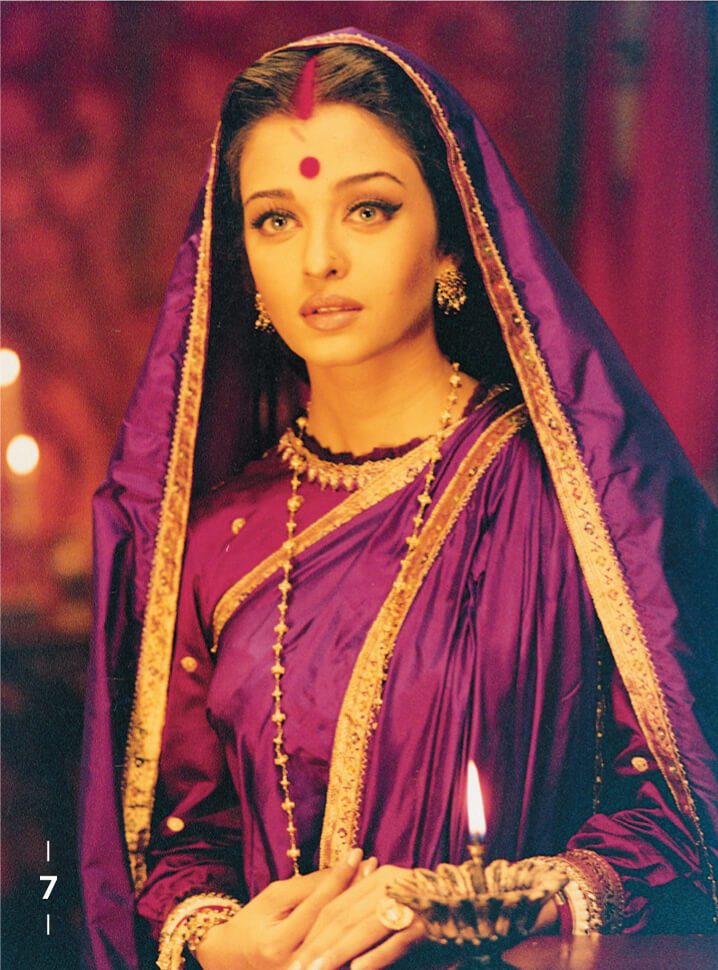

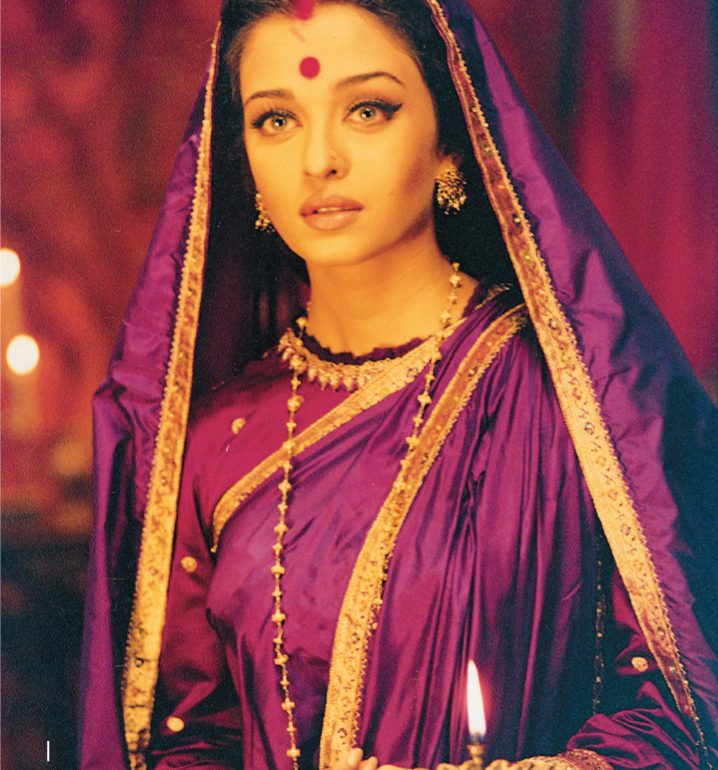

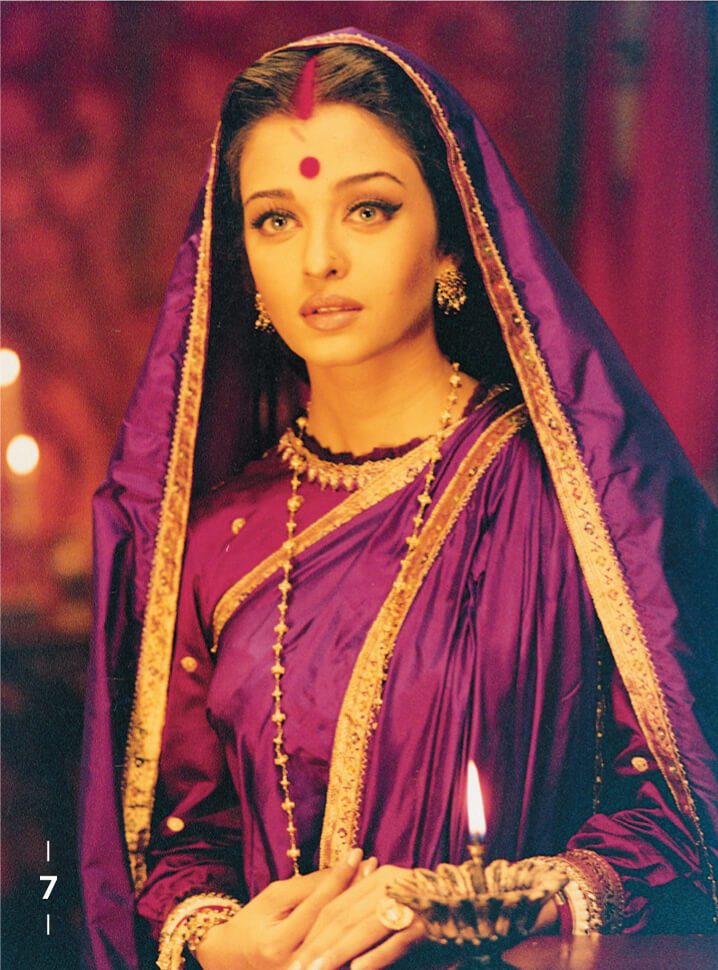

Leading Ladies – Madhuri Dixit and Aishwarya Rai (left and right) in the 2002 film, Devdas

-

-

Aishwarya Rai in Devdas

Storytelling has also changed. “Previously when you were writing a film that you wanted to do well across India, you wouldn’t root it in one city,” says Raghavan. “We often wouldn’t have surnames so you couldn’t tell which part of India they were from. That is changing. Last year there was a film set entirely in Calcutta which used local language and actors. Rootedness is being accepted.”

Not all stories were easy to introduce to India. While casting his Bollywood version of Macbeth – Maqbool – Bhardwaj approached a big Bollywood star. “He read the script and said he enjoyed it,” he says. “But then said ‘he is a loser’. I laughed and told him ‘that’s Shakespeare’s fault not mine’. He couldn’t get what I was trying to do.”

Some contend that the stories themselves are not that new. “It is more the treatment, not so much the story that has changed,” says Sippy. “Maybe some ways of storytelling have changed.”

The huge success of the 2012 film Vicky Donor, a romantic comedy about a sperm donor, was seen by some as a sign of India’s growing acceptance of new lifestyles. “Ideas are global,” says Kishore Lulla, Executive Chairman of the film studio Eros International that created the film. “There is no such thing as ‘just for Bollywood’. It depends how you package it. We are in talks with an American studio who would like to remake Vicky Donor in the US.”

Hollywood may be borrowing from Bollywood, but it is a symbiotic relationship. “From 1997 to 1998, India begun to be liberalised,” says Dudrah. “The government opened the borders and allowed foreign investment. The opening up led to Bollywood partnering up. There were new forms of business and filmmaking opportunities.”

Eros are also due to partner with HBO to create a Bollywood-based version of Entourage, the popular US TV series following a Hollywood film star and his friends. Scripts are not the only thing India has adapted and adopted from the States. Studios, rather than individual producers, are now funding the projects.

“Bollywood today is where Hollywood was in ’40s and ’50s,” says Lulla. “Studios have the financial muscle and distribution. What Hollywood achieved in 50 years, Bollywood will do in 10.”

“The corporates mean that the industry has become more organised,” says Bhardwaj. “When it was just independent producers, it was a mess.”

While Hollywood studios are now notorious for pushing re-runs and re-makes, Indian studios seem to be more open-minded, able to spread the risk.

“Many smaller films with young actors are being made because the corporates support it,” says Roshan. “It is easier now that the corporates have come. The new directors, writers, actors get breaks and a chance to work.

“On the flipside it has become so easy that people are not working hard. That’s why you see short films that come around for a few weeks then disappear. If I’m putting my own money in the film, I will see to it that I get my returns back. But if I am making a film for someone else then I don’t have that pain. I just think ‘let’s do it, we’ll see what luck has got’.”

While the West is playing it safe, Bollywood is testing its boundaries.

With thanks to Eros, Reliance, Sobo Films and Media and Entertainment at The Confederation of Indian Industry

Recent Comments