The scene of the 2018 Gaggenau Sommelier Awards ceremony gala dinner, held at the Red Brick Art Museum in Beijing

More than sheer knowledge of wine, it takes dexterity, impeccable service and the ability to inspire the diner to be a top sommelier, as the finalists of the 2018 Gaggenau Sommelier Awards in Beijing discover. Sarah Abbott, a judge at the final, describes the peaks of that fine wine world

We are watching Kei Wen Lu about to extinguish a candle. He pinches – does not blow – the flame out. I breathe a secret sigh of relief, and discreetly tick my scoresheet. Beside me, fellow judges Annemarie Foidl, Yang Lu MS and Sven Schnee mark their scorecards.

Kai Wen, one of the 2018 finalists

Such is the assessment of elite sommellerie. Kai Wen won the Greater China heats of the Gaggenau Sommelier Awards, and he is now performing the “decantation task” in the grand final, in Beijing. He faces a room of Chinese and international press, and the relentless gaze of we four judges.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

For this task, there are 40 elements on which our young finalists are judged. Decanting seems straightforward, perhaps: open a bottle, pour it into a decanter, leaving any sediment behind, and serve a glass to each of your four guests. It is the attention to tiny details that transforms the everyday to the excellent, and the exigent to the sublime.

This task has been created by judge Yang Lu, Master Sommelier and Director of Wine for the Shangri-La Group. Yang has passed the toughest sommelier exam in the world and knows what it takes. Mentor and hardened veteran of elite sommellerie, he challenges these young recruits with his relentless eye for excellence.

From left to right: David Dellagio, Mikaël Grou and Emma Ziemann, three of the finalists, in front of Gaggenau’s wine storage cabinets

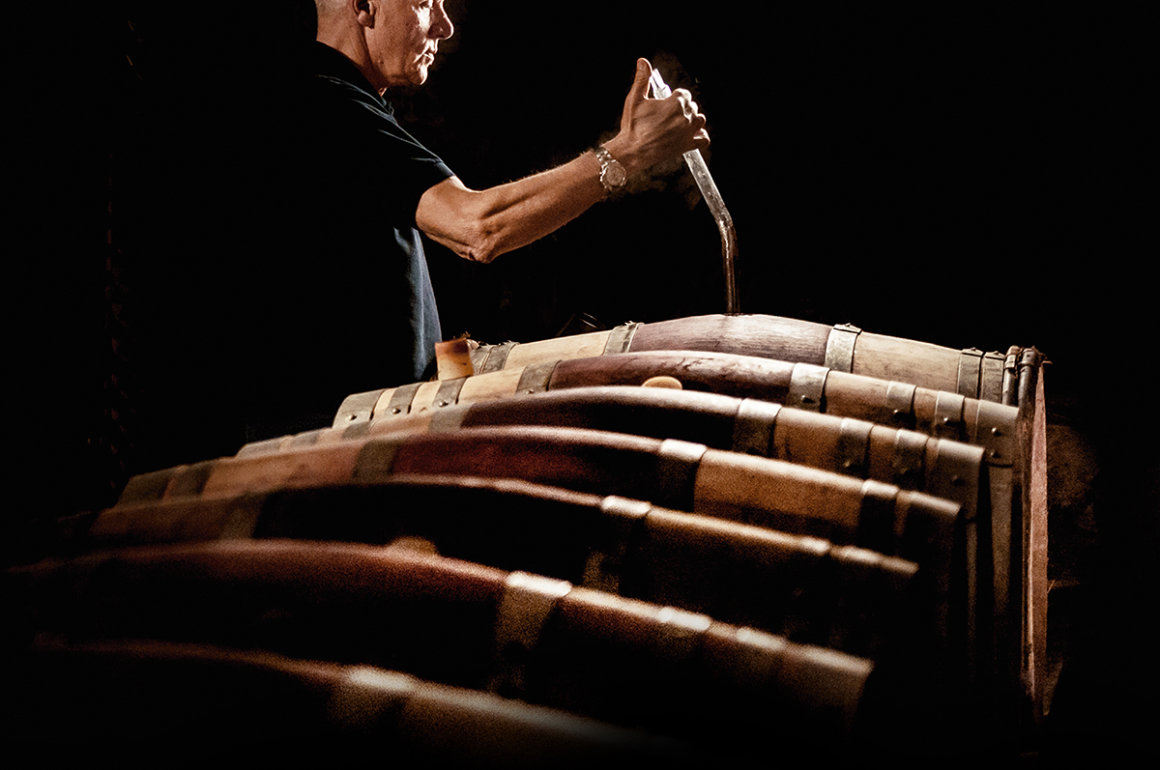

The guéridon must be wheeled smoothly to the right of the host. The bottle must be eased from the shelf and placed gently into the wine basket. You must remove the capsule foil cleanly, and the cork smoothly, without disturbing the bottle in its cradling basket. Ah, but have you remembered to light the candle before you’ve uncorked the bottle? And to wipe the bottle lip with a clean napkin before extracting the cork? And have you assembled those napkins on the guéridon before you bring it over? Kai Wen’s hand is steady as he decants the wine over the lit candle. The room is eerily silent, a camera man is panning up close, and Kai’s every move is magnified for audience and judges on TV screens.

Yang has set traps. He has planted dirty glasses. And he has set out two different vintages of the requested wine. One ‘guest’ decides that she doesn’t fancy the red wine. Can she have a glass of sparkling wine instead? Contestants will lose six marks if they pour the sparkling before serving the other guests their decanted red. More points are ripe for deduction for forgetting the side plate or to offer to remove the cork, or for unequal pours. And for puffing out that candle.

Kai Wen is friendly, focussed and diligent. He avoids most of the traps and completes the decantation within the scarce nine minutes.

Read more: How politics trumps science in the GMO debate

Despite the rigour and specificity of the marking scheme, the personal style of each contestant comes through. Emma Ziemann is the Swedish finalist. Confident and authoritative, she impresses by greeting the judges as if in the theatre of a busy service. She holds our eye, and sails through the decantation, coping well with a dastardly technical question from Yang – designed to put the contestants off mid-pour – about the Saint-Émilion classification.

The pressures of time and occasion are merciless, and most evident during the blind- tasting challenge, in which contestants must taste, describe and identify seven wines and drinks. All identify the Daiginjo Sake without problem, but the old stalwart of French crème de cassis liqueur stumps several. These non-wine beverages are served in opaque black glasses, masking any colourful clues.

Mikaël Grou, the eventual winner of the 2018 Gaggenau Sommelier Award

South African finalist Joakim Blackadder shows relaxed charm and cool humour. Mikaël Grou, the French finalist, excels. Engaging and poised, he tastes, describes and correctly identifies five of the seven wines and beverages within the allotted twelve minutes. Mikaël impresses for the range and precision of his technical vocabulary, and for his enticing, consumer-friendly descriptions.

All instructions from the judges are spoken and may be repeated only once. It is easy to miss a critical detail. Young, enthusiastic Zareh Mesrobyan is the British finalist. Originally from Bulgaria, he works for Andrew Fairlie’s renowned eponymous restaurant in Scotland. Annemarie Foidl, head of the Austrian Sommelier Association and our chair of judges, gives the instructions for the menu pairing task: Zareh has thirty seconds to read the menu, and four minutes to recommend one accompaniment for each course. “Please include one non-alcoholic beverage and one non-wine beverage.” Zareh seems to love the task. He does triple the work, giving not one but three creative and detailed pairings for each course. Sadly, he cannot gain triple marks.

Read more: Artist Rachel Whiteread on the importance of boredom

The structure of sommelier competitions is well-established around the world, and ours includes many of these classic elements. But Gaggenau is looking for that extra spark, so Annemarie has devised a new task called Vario Challenge, after Gaggenau’s new wine storage units. Built into the stage wall are several wine storage units, calibrated to different temperatures. Each contestant must work their way through a delivery of twelve wines, describe each wine to the judges as if to a customer, and put the wine in the correct cabinet. Swiss finalist, Davide Dellago, excels, wheeling between judges and Vario with grace, and summing up the style and context of each wine with wit and confidence.

The world of sommellerie can seem elitist and arcane. The cliché of the stuffy sommelier

persists, rooted in an increasingly faded world of starched cloths and manners, and of

knowledge used as power, not as gift. As Yang Lu says to me later, it’s critical that sommeliers retain their love for and connection with customers. They must work the floor. Taking part in competitions is a means to an end, not a job in itself.

And what is that end? After a gruelling day of competing, our six finalists worked the floor at a gala dinner. Here is the theatre where sommellerie performs. And this was quite a production. The Red Brick Art Museum, a young, bold architectural venue in Beijing’s art district, was a hip, stylish space. Banqueting tables were dressed in silver and late-season flowers and berries, evoking autumnal birch and harvest bounty. It was time for our young sommeliers to serve not clipboard-wielding judges, but honoured guests.

Chef André Chiang plating up for the gala dinner

Our finalists presented six wines with six courses, to each table. The menu was created by André Chiang, the Taiwanese-born, Japanese-raised and French-trained chef, who won two Michelin stars for his Singapore restaurant, Restaurant André. Thoughtful and visionary, Chiang is a revered superstar of contemporary Asian culinary culture. So, the pressure was on.

South African finalist Joakim Blackadder

The finalists had been given just two hours on the previous day to taste the wine with the judges and acquire the facts they needed to tell their wine stories with conviction and colour. All the wines were Chinese. Just five years ago, matching exclusively Chinese wines to food of this nuance, precision and individuality would have been a tall order. Big, gruff, blundering Cabs were the rule. But the ambition and accomplishment of Chinese winemaking today has soared, and these were excellent matches. So it was that our contestants were able to tell a new story of Chinese wine to guests. Of six different styles, of six different grapes, and from six different regions.

Grace Vineyard Angelina Brut Reserve 2009, an intricate and sabre-fresh, champagne- method sparkling, was served with the pure, enticing first course of braised abalone with green chilli pesto and crispy mushroom floss.

They presented Kanaan Winery’s mineral, elegantly aromatic 2017 Riesling with the softly textured, seductive second course of asparagus, caviar broken egg and non-alcoholic Seedlip Garden 108 herbal spirit.

Read more: PalaisPopulaire & Berlin’s Cultural Revolution

Contemporary Chinese wine is inspired by European traditions, but the deeply traditional aged 2008 Maison Pagoda Rice Wine thrilled our sommeliers with its tangy, nutty intensity. Both strange and familiar, it recalled old Madeira or Oloroso, but with a deeper, salty well. It was superb with the dark marine crab capellini, laksa broth and curry-dust sea urchin.

There is one dish that Chef André never removes from his restaurant menu (I suspect, having tasted it, for fear of riots). European culinary tradition and Asian technique come together in this dish of foie gras jelly, black truffle coulis and chives. Part jelly, part mousse, this intelligently decadent dish was paired with the delicately sweet, honeyed 2014 Late Harvest Petit Manseng from Domaine Franco-Chinois.

The first and only red of the evening was perfumed and confidently understated. 2015 Tiansai Vineyards Skyline of Gobi (yes, as in the Gobi Desert). This scented, floral and plush syrah/viognier was a surprisingly successful pairing with chargrilled Wagyu beef.

You know that a wine culture is developed when signs of an iconoclastic counter-culture peek through. Our final wine of the night was, in essence if not in name, a natural wine. Bottled in one-litre flip-top bottles and made from the too often dismissed hybrid grape vidal, the 2017 Mysterious Bridge Icewine was as wild and fresh as the mixed-berry jelly dessert with which it was served.

Our sommeliers told these stories. They blossomed in service, freed from the heat of their earlier competition but also strengthened by it. They delighted our guests with their own delight in these new discoveries. This is the calling of sommellerie – to notice, describe and share the beauties of wine with new ideas of what is beautiful.

In the end, Mikaël Grou was victorious. But, as fellow judge and head of Brand Gaggenau, Sven Schnee said, each of those young sommeliers were winners. They, and we, were touched by this experience of Chinese history, culinary culture and pure vinous potential.

Discover more: gaggenau.com

This article was first published in the Winter 19 Issue

Recent Comments