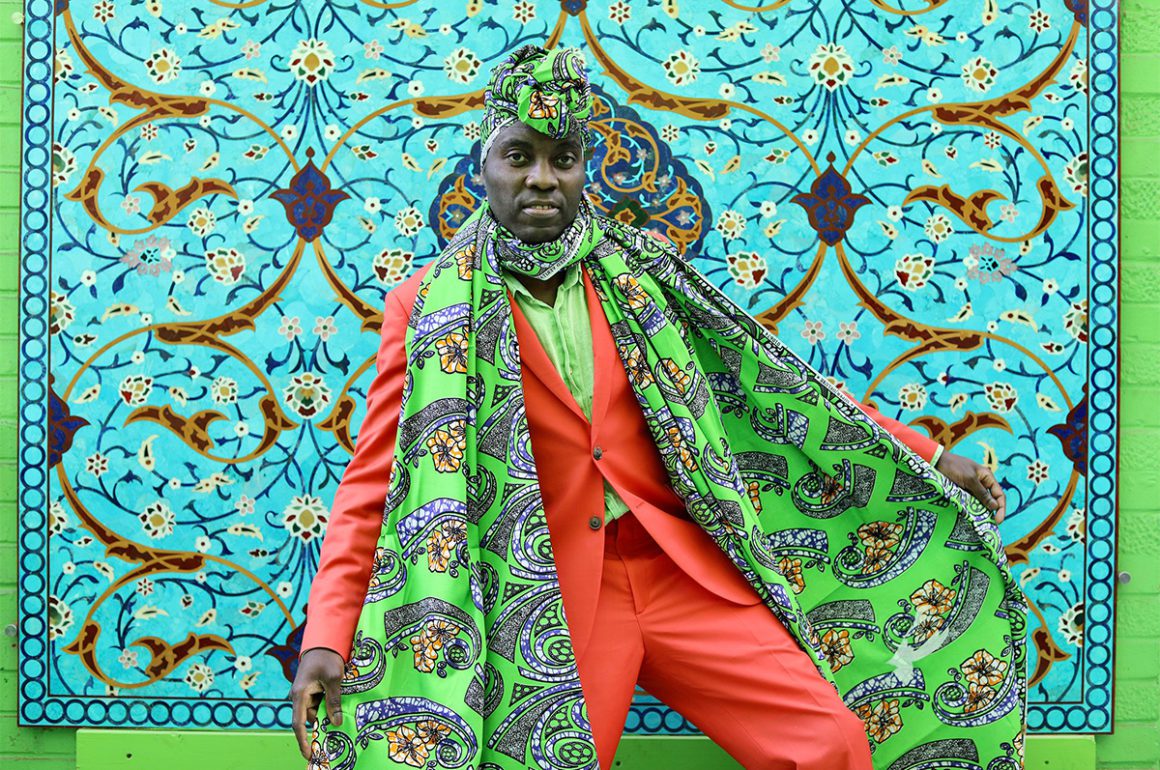

Iwan Lukminto at the Tumurun Museum in indonesia

Iwan Kurniawan Lukminto is VP of Sri-Tex, one of Indonesia’s original and fastest-growing textile manufacturers, which supplies product to garment factories across the world, manufactures uniforms for 33 nations’ armed forces, workwear for global corporates, and merchandise for a significant number of global fashion multiples. Lukminto speaks with LUX Leaders and Philanthropists Editor, Samantha Welsh, about art philanthropy and national identity in a post-colonial world.

LUX: You are a much-awarded textile entrepreneur, what do good governance and philanthropy share in common?

Iwan Kurniawan Lukminto: Well, the basics of any good organization, whether it is focused on society where philanthropy is key or on corporate shareholders where good governance is required, both need to promote accountability, transparency, and adhere to ethical conduct. Both aim to have positive impacts. At the end of the day, the basics are the same; the difference lies in the contexts and settings where they are focused.

LUX: What is it about art philanthropy that appealed, as opposed to other ways of giving back to communities?

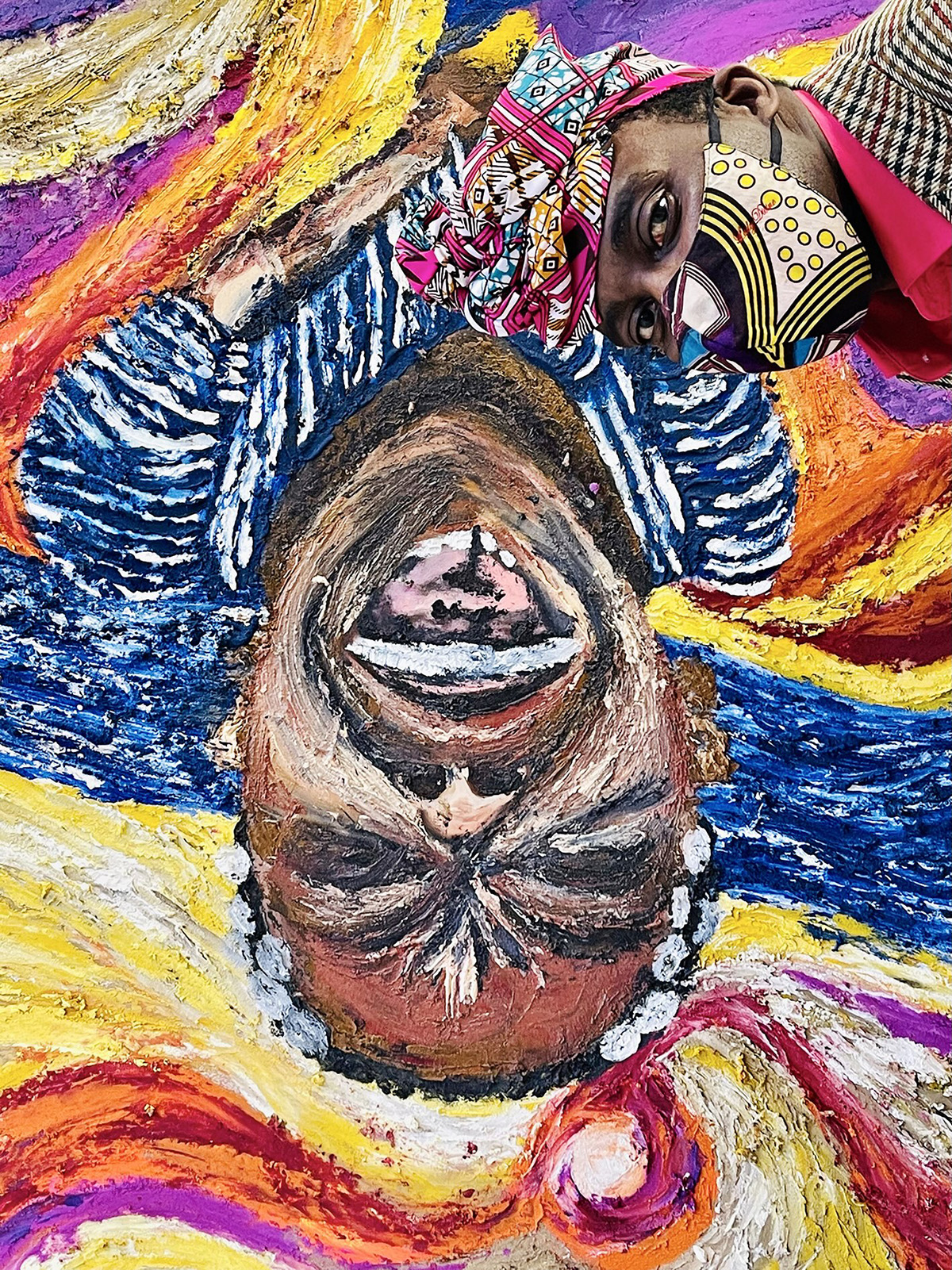

IKL: Art has always been my passion. In art philanthropy, we focus on the arts, starting with Indonesia’s art scene, which I feel is still lacking support from both the government and the private sector, despite its good potential and quality. Indonesia, with its unique historical background and multicultural diversity, has much to offer, yet it remains under the radar of the international art scene. Thus, I aim to preserve and promote it, hence the birth of the Tumurun Museum.

Art philanthropy interests me particularly because it is enriched with human experience. It tells stories about the past, the present, and the vision of the future in creative, thought-provoking ways. In art, we catalyze the essence of knowledge, looking beyond science, mathematics, politics, etc., and translating it in the most aesthetic way. For example, consider how Alicia Kwade talks about mass and physics by placing a globe on a plastic chair.

In short, art intrigues and excites me, making me see outside and beyond the box. Thus, I want more people to have the same experiences.

Follow LUX on instagram: luxthemagazine

LUX: What was the founding vision for Tumurun Museum?

IKL: Tumurun aspires to be a flag bearer for Modern and Contemporary Indonesian art while remaining inclusive and receptive to global artists who dialogue, engage, and enrich its core collection.

LUX: How are audiences responding to its outreach programs?

IKL: The city of Solo is one of the art centers in Indonesia, focusing on performance art, while Yogjakarta city (around 100km away) is another art center in Central Java. The absence of an art museum in the region enhances our visibility and perception among our audience.

Iwan Lukminto founded the Tumurun Museum, Surakarta, in 2018 to house the extensive collection of modern and contemporary art amassed by the Lukminto family.

LUX: What was the art landscape when the so-called East Indies was a colony of the Dutch?

IKL: There are broadly two categories of audiences: the art community and those outside of the community. For those from the community, it is again subdivided into a few groupings: for those who are from the home community, such efforts are very much appreciated as curated narrations are not common in the scene, and any such effort would spark conversations for new findings and alternative perspectives, which is always positive. For those from the outside, outreach programs allow them a chance to come close to art that is not part of their daily life. Their appreciation might not be within the art historical context, but the joy and, more importantly, the curiosity of looking at something new, something beautiful, or even something strange are real.

LUX: How are artists developing new narratives from exotic ‘Utopia’?

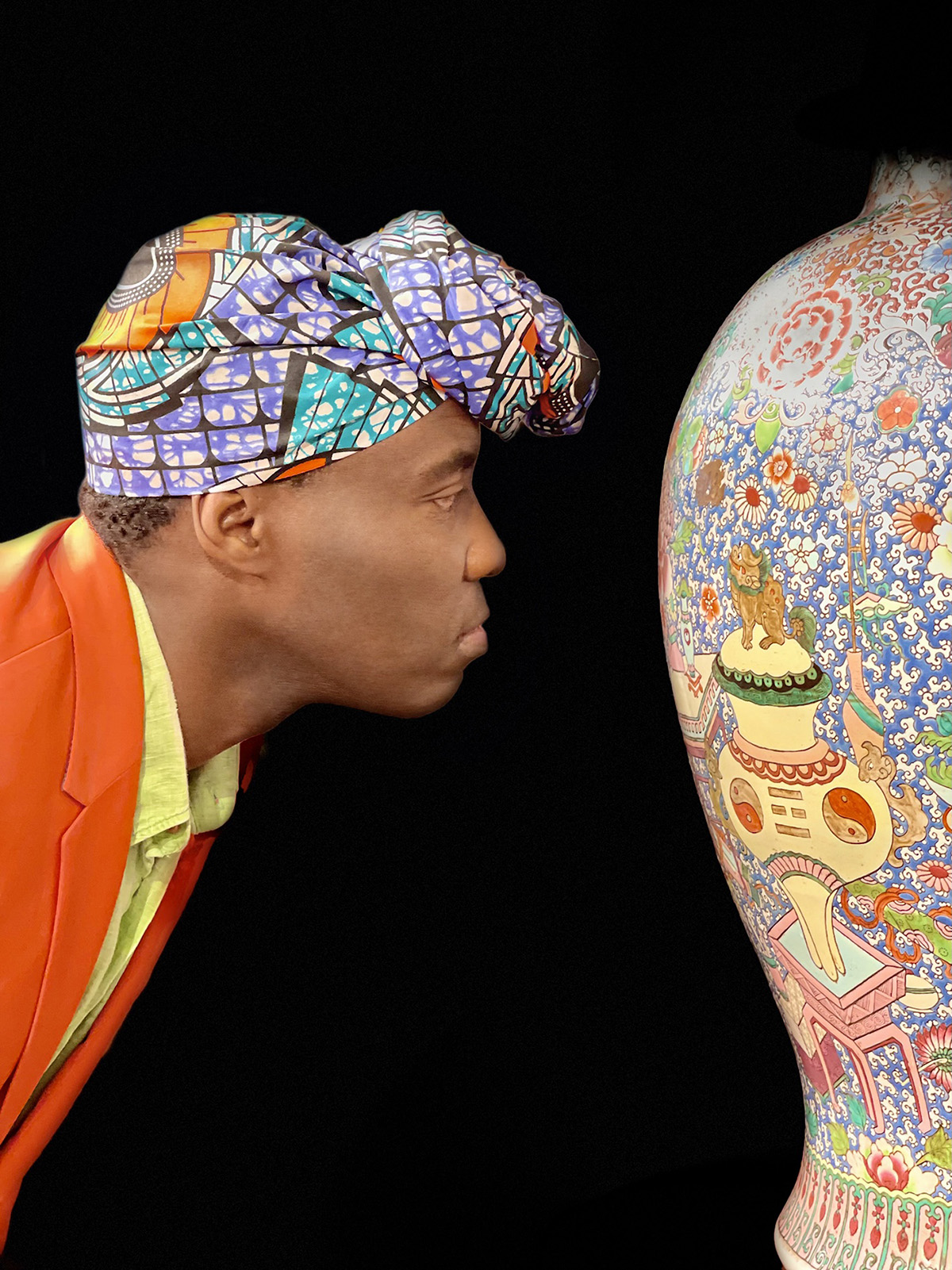

IKL: During the 18th to 19th century, these Western artists were amazed by Indonesia’s tropical land and began recording all they saw and experienced with drawings and paintings. Then, Indonesian artists were directly taught by Western artists on how to draw and paint, strictly following the rules of Dutch School teaching with Romanticism style of portraiture or landscapes. This teaching persisted for generations until the 1930s, when the revolutionary era emerged, and artists began to oppose this approach to art-making.

Indonesia is not solely about beautiful landscapes and pretty people; we also face social issues such as poverty, discrimination, and genocide. Therefore, this group of artists shifted to freeform expression and discovered the true “Indonesian” identity in their paintings.

LUX: Is this shaping a new identity for the nation?

IKL: Indonesian modernist artists began to embrace nationalist “characters and elements” in their works, which was a direct critique of the colonial painters who, according to the modernists, were not depicting the real Indonesia. I don’t believe any art movement alone can shape a new identity for a nation. However, art always reflects the spirit of the time. After the WWII, with pro-independence movements rising all over Southeast Asia, the art of that era also reflected a desire for independence, respect for indigenous cultures and art, and the aspiration to be authentic Indonesians. This sentiment is not only evident in visual art but also in literature, music, films, and other forms of expression.

Read more: Hansjörg Wyss on his pioneering work in conservation

LUX: Can this benefit Indonesia’s international relations?

IKL: Yes. For centuries, art has been a tool for international relationships. Art speaks a language so gentle that many willingly listen, yet so powerful that it can incite nations to rebel. Regarding Indonesian art, it initially served as a promotional tool where the Dutch showcased the beautiful landscapes and cultures of Western Indonesia.

If this is referring to Tumurun, then I believe that as a private museum whose core collection aims to showcase a narrative of modern and contemporary Indonesian art within a local/Asian context and aspires to expand the dialogue to a global context, it would always be useful for the purpose of education, dialogue, and exchange. This contributes to a greater understanding and appreciation, which are the foundations of all foreign relations, between countries and, more importantly, between cultures.

LUX: What do you hope your legacy will be?

IKL: Tumurun originates from the Javanese phrase ‘turun temurun,’ which literally translates as “passing on from generation to generation,” standing at the heart of the founding principle of the museum. Committed to education, Tumurun collects, preserves, and interprets modern and contemporary art, and explores ideas across cultures and regions through curatorial and outreach initiatives. We hope that by standing proudly with our vision and mission, the collection could inspire more generations to come.

Recent Comments