Two cameras, one journey, two childhood friends — and eighteen days to shoot their surroundings across the American West. Maryam Eisler and Alexei Riboud had followed separate paths for 38 years. Would the two photographers’ love of the still image converge their paths? LUX finds out

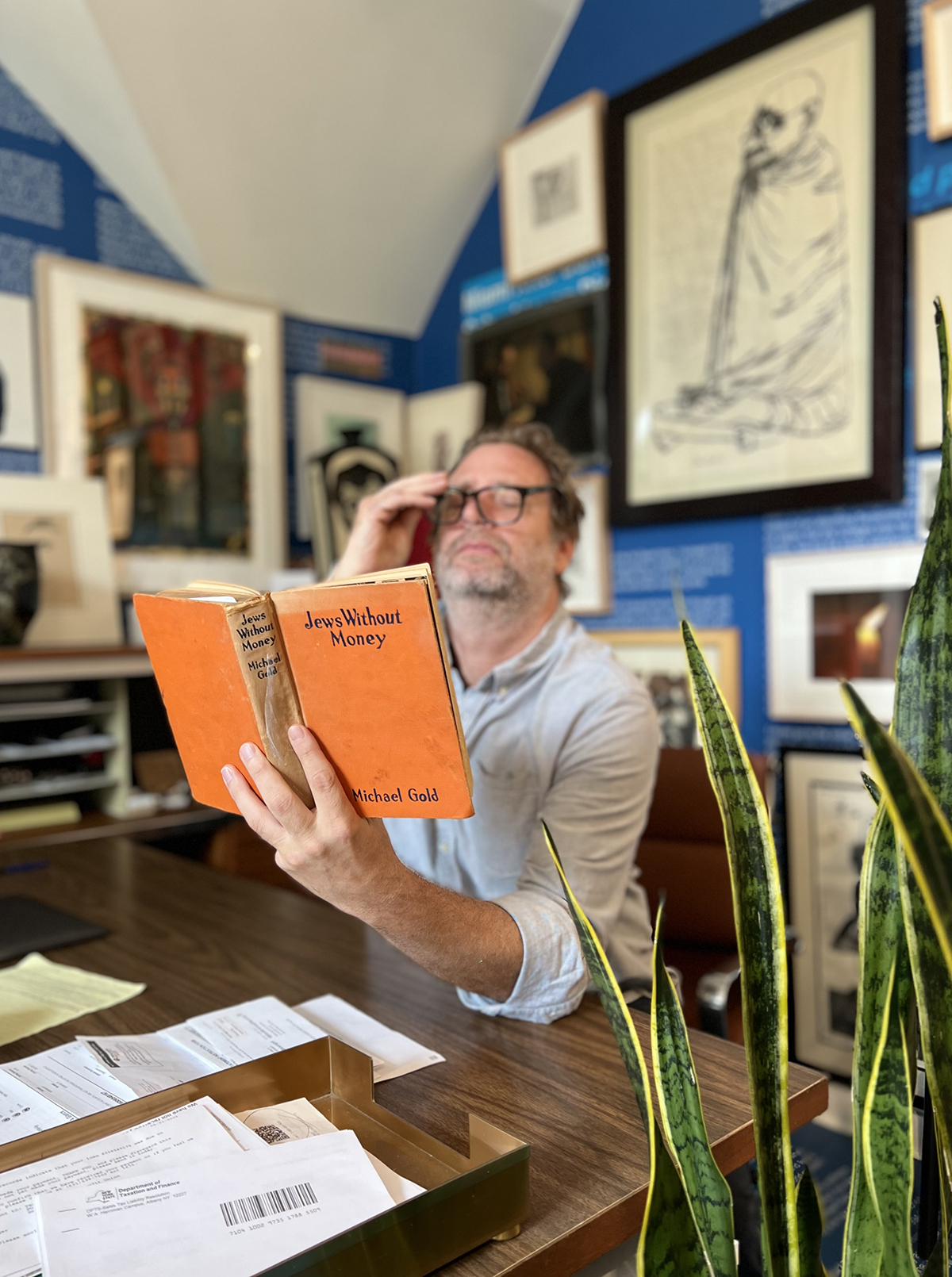

After graduating from high school together in Paris, in 1985, Maryam (then Homayoun) Eisler and Alexei Riboud parted ways; Eisler to the world of business, first at L’Oréal and then at Estée Lauder in London and in New York; Riboud to the world of graphic design and photography, in Paris, New York and Johannesburg, following in the footsteps of his celebrated parents, photographer Marc Riboud and sculptor, author and poet Barbara Chase-Riboud.

Lights glowing faintly, flickering occasionally on an old, lonesome sign for a motel on the border of Marfa, Texas, that is long gone; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

Nearly four decades later, in early 2024, the art world brought them back together, for a three-week American road trip through parts of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah, photographing space, place and people along the way in a form of visual dialogue. In, and in-between locals travelling by car, well over 2000 miles, from Houston to El Paso… Marfa, Presidio and White Sands to Santa Fe and Canyon Point… they’d hop out of the vehicle at any given moment, and say ‘See you in an hour!’, and go their respective ways, out in the wilderness, reacting to circumstances as they came across them, vowing not to give any advice to each other on what or how to shoot. Not even sharing their images until they returned home.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Laughing, the two recall the fifteen U-turns they took on one straight 22 mile road from Espagnola to Ghost Ranch, because they kept seeing elements they wanted to capture, not to mention the 24 hours they spent obsessing over a missed opportunity, a derelict 1950s motel, now far behind them.

White sands National Park, New Mexico, photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

The images that Eisler and Riboud produced provide an intriguing study of contrasting perspectives and techniques. They both certainly shared a road trip, but in artistic terms (and fortunately for the viewer of the works), they were on parallel journeys, each producing compelling results. As Carrie Scott, the art historian and curator, notes: ‘I am buoyed by the conversation here between these two artists. Maryam and Alexei are shaping our perceptions of the American West through their dual lenses, which in turns gives us a moment to reflect on our fixed perspectives.’ It’s a far cry, as Scott adds, from the ‘longstanding tradition in American photography, dating back to the 19th century, of a singular male voice and viewpoint.’

A friendly security guard at the Concordia cemetery in El Paso, TX giving Eisler and Riboud directions to the tomb of John Wesley Hardin, the man who earned himself a reputation as one of the Wild West’s most pernicious gunslinging outlaws; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

Riboud is attracted to the outskirts and grey areas, the transitional spaces and borders where he finds the elements to compose his photographs. His approach has been refined over many years of shooting in diverse locations, including Havana, Tokyo, Johannesburg, Mumbai, Shanghai, Chicago and of course Paris — usually with a focus on the peripheral spaces within or next to large cities.

A railway track cutting through the town of Marfa, Texas, photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

‘I like wandering into places I have never been to, especially on the margins of well-known locations, exploring the counter-space of an established geography. My photography is about experimentation. I gather fragments from urban landscapes, in an effort to capture innate structures’, says Riboud. ‘On this trip, I was drawn to the outskirts of towns, and to the frontiers between human settlements and the unpopulated natural environments.’

A Navajo Nation dancer performing an indigenous ritual dance impersonating animal spirits, Page, Arizona; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

‘This trip was a huge challenge for me’, says Eisler: ‘My focus has always been on the figurative and more specifically on what I like to call the ‘Sublime Feminine’ in its physicality and in its essence. I had to push myself to work in a new way, this time around, moving away from body landscape to natural landscape.’ But would she find parallels between nature and figure?

Read more: Maryam Eisler: Intimate Landscapes

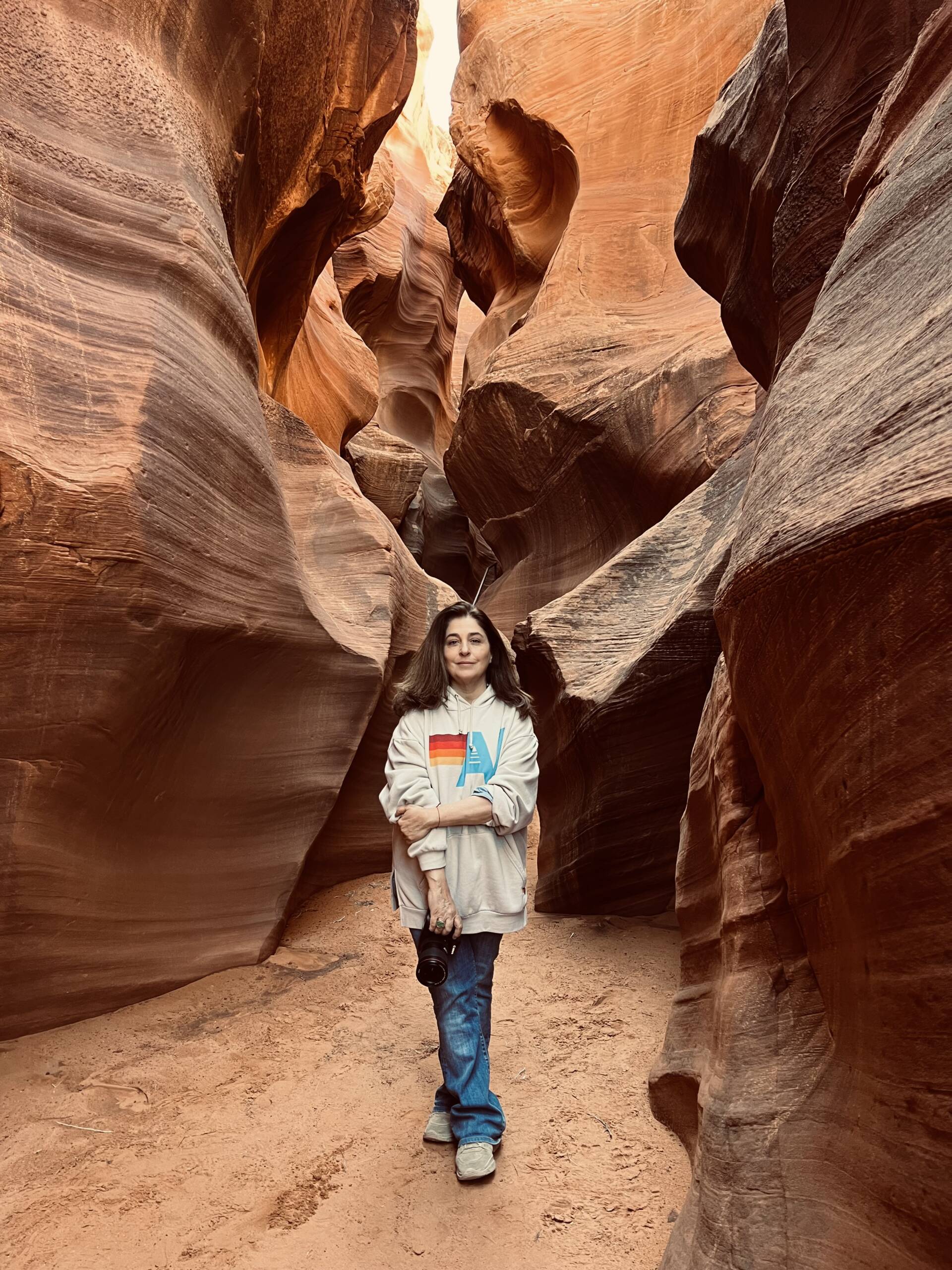

‘In my work, I always talk about female ‘body architecture’ in dialogue with spatial architecture… its curvilinear slopes, its nooks and its crannies, its valleys. I have often explored this theme in big, barren, hostile nature, from Iceland to Mexico and beyond, except this time the female figure was not there to be photographed. I also surprised myself in adopting a new way to work… primarily using a wide angle lens (which I never do) in order to capture as much of the big sky and vast land as my lens could take in. I wanted to visually overdose on the nature that surrounded me!’

In between walls of a teared down house in the border town of Presidio, Texas, photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

It’s no wonder that these two photographers operated quite differently during the road trip. They are two very different characters. Eisler’s made a quicksilver shift from business and writing to art, and has the smiling, knowing grace of a meditative guru while retaining the poise of a terrifying boss.

Alexei Riboud, photographed by Maryam Eisler on US Highway 90 near Van Horn, Texas, 2024

Riboud, on the other hand, projects a laid-back-almost-to-horizontal suave creativity. Nonetheless, both have clearly forged a deep connection that transcends their decades apart and their contrasting artistic and technical sensibilities.

Homeless young man in downtown Houston with a t-shirt depicting Martin Luther King and Malcolm X’s encounter; Houston, Texas; photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

To the extent that the origins of their photography have links, they are serendipitous, through a mutual interest in graphics. Riboud, who did graphic design for an advertising agency in South Africa in the 1990s, began to photograph on weekends, and enjoyed it enough to make it his main focus.

Derelict remains of the former Art Deco movie theatre in Marfa, Texas; The Palace, closed since the 1970s, is now an illustrator’s studio; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

At L’Oréal, Eisler’s involvement in the development of ad campaigns — what she calls ‘surface beauty’ — revved up her dormant love of visual story-telling. Today, one can experience both the outer and inner dimension in her exploration of the ‘Sublime Feminine’. Laughing, she recalls her father’s niggling voice in her head, asking her what she was doing with that ‘love of photography’ she had so enthusiastically written about in her college applications? But life after the (Iranian) Revolution would dictate otherwise, until years later.

Looking through the US-Mexico border wall in El Paso near Amara House at La Hacienda, an organisation working to inspire connection beyond borders through mutual understanding and meaningful action in pursuit of narrative systems, and personal change; El Paso, Texas; photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

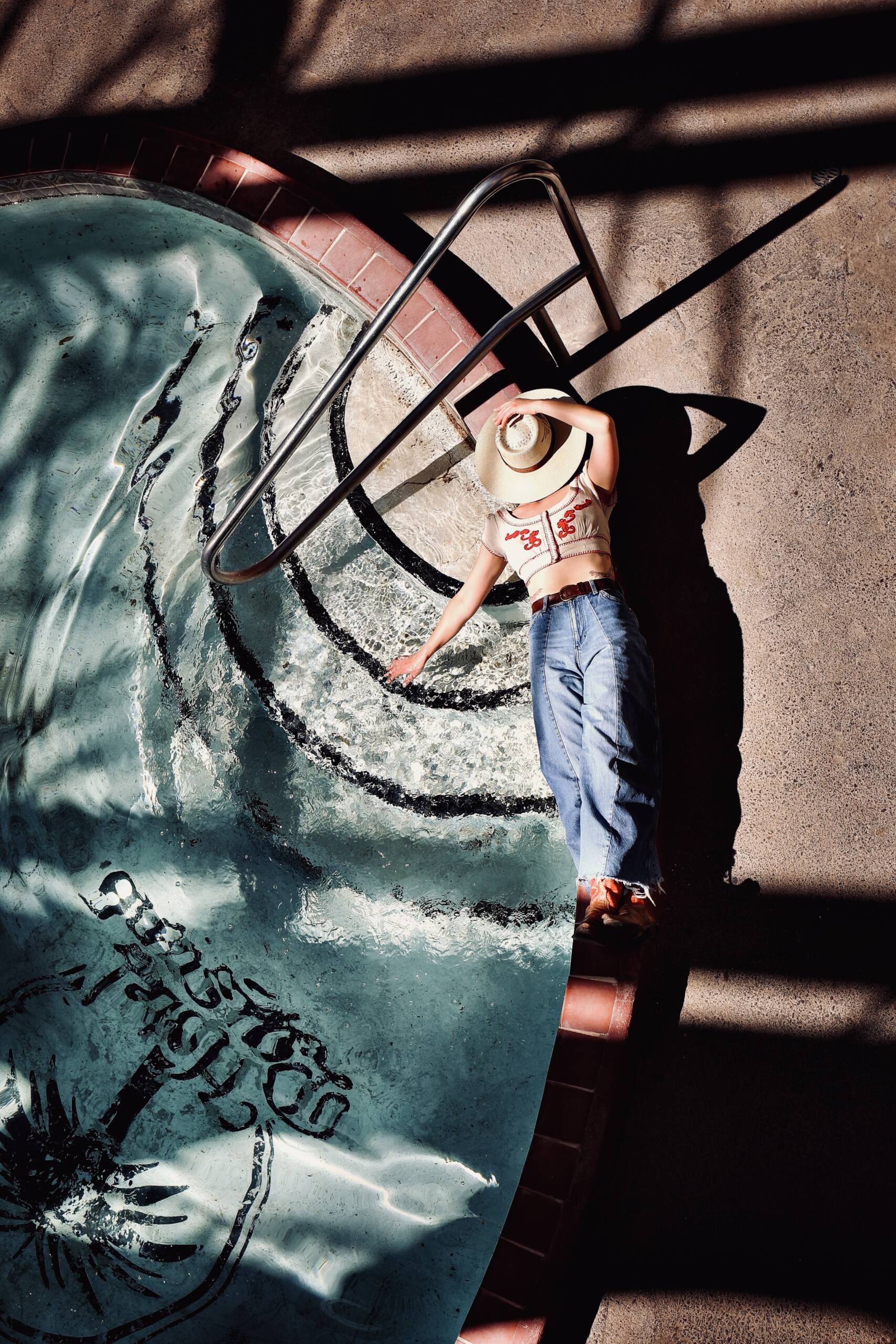

Both Alexei and Maryam have indelible memories from their trip. Alexei reflects back on the town of El Paso, near the US-Mexico border: ‘‘There was the feeling of being at a crossroad of narratives with stratified areas, unsettled spaces in transition.’ Maryam recalls a moment on the border of Utah and Arizona: ‘A hypnotising Native American ritual dance made me think deep about indigenous cultural history and the suffering that the native people have and continue to endure… I was completely mesmerised by the strength of the dancers storytelling through moves anchored deep in tradition.’ Riboud points to the gentrification of Marfa, Texas: ‘Beyoncé and Jay-Z just bought a house there! You get a sense that it’s rapidly changing from the isolated artistic outpost that Donald Judd built all those years ago; the city is now attracting newcomers, as real estate prices are booming!’

Alexei Riboud, photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

The two photographers’ contrasting visual perspectives provide fertile ground for dialogue, and – as Scott says, ‘a new, layered perspective on the complex reality of the 21st-century American West. Where Maryam’s portraits provide narrative depth – each portrait becomes a story, a window into the lives, cultures, and experiences of individuals within that vast expanse – Alexei’s focus on the landscape reflects on America’s historical relationship with western expansion.’

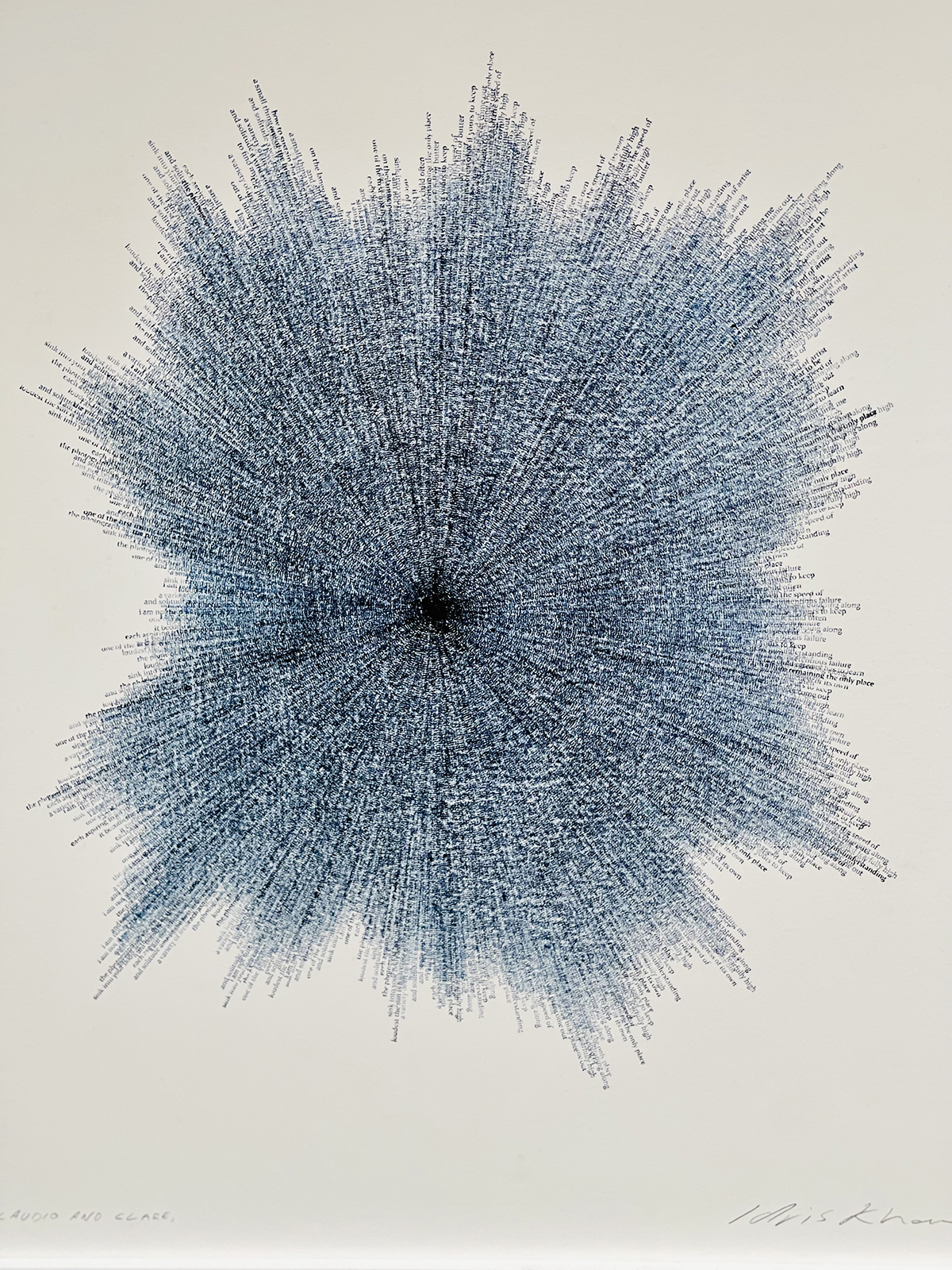

Maryam Eisler, photographed by Alexei Riboud, in Upper Antelope Canyon, Arizona 2024

Riboud praises Eisler’s link between the female body and the architecture of space and place, as well as her graphic eye mingled with sensuality. For Eisler, it’s Riboud’s conceptual visual rendering—‘almost like a painting’ — that stands out above all. ‘The lens Alexei uses enables him to capture space and light in a very unique manner. The end result is subtle, painterly and beautiful, with incredible hues of light pinks and accents of deep purples in some instances. I think Alexei uses light to paint.’

Along the banks of Rio Grande river near Los Alamos, New Mexico. This is the view from the House at Otomi Bridge that frequently hosted Manhattan Project scientists. A team room and restaurant at the time – once post office and train station – where Oppenheimer kept a standing reservation for whenever he wanted to dine; New Mexico; photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

Kamiar Maleki, Director of Photo London, expresses their effect on one another – their oscillations, recalling Maryam’s ‘evolution from exploring the female figure to this more recent body of work’ and its ‘profound shift towards celebrating the Sublime in a new and different way – as displayed in Mother Nature‘, as well as ‘in the vast potent (waste) lands of the American West landscape.’

Maryam Eisler, as photographed by herself at Prada, Marfa, by Elmgreen & Dragset in Valentine, Texas, 2024

For Alexei, it’s his ‘minimalist elegance, presenting viewers with unexpected compositions that speak volumes through their simplicity.’

Portrait of an outsider Texan artist, James Magee, a dear friend of the painter Annabel Livermore, whose painting he sits in front of, and who various writers have described as his alter ago, a relationship referred to by The New York Times as ‘a tough act to follow’, photographed in El Paso, Texas, by Maryam Eisler, 2024

Reflecting on the journey, Eisler says, ‘I still recall the vastness of land and the ever-changing skies and clouds. We could’ve produced an entire body of work on the clouds of New Mexico; the evolving light and its plethora of shades… It was sky theatrics every day! As we drove on Interstate highways, I could not help but feel a deep sense of inner peace.

Alexei Riboud in White Sands National Park, New Mexico, photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

In fact, I had a memorable moment in White Sands National Park, as the sun was setting down amidst scarlet and purple skies. I recall seeing Alexei, camera in hand, standing on the opposite hill, akin to a dot in the greater universe… And for just a second or two, which felt like eternity, I took off mentally into a parallel state of mind, engulfed by Mother Nature. It was so powerful’.

Weary billboard with missing parts north of El Paso in the vast plains of Texas; photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

‘I think the camera changes what you see, particularly when it’s your first experience of a place, of a unique location’, says Riboud. ‘Something happens that you can’t control; it’s your subconscious working, through the frame of the camera, on the construction of the image.’

Roughly halfway between Van horn and Valentine on U.S 90 reside crumbling buildings seen through a chain link fence: a one time significant railway dewatering station, now turned ghost town of Lobo, Texas; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

And when it’s not the camera, there are parallel – or, rather, oscillatory – expressions, from a writer they met along the way. Glimpse below the poem ‘Eileen’, written by poet Amanda Bloom in West Texas. Her series of linguistic short takes provide a further mode of expression, imbricating the tapestry of their journey:

Poet Amanda Bloom lying by the pool of the iconic ‘Hotel Paisano’ in Marfa Texas where the cast of the 1956 Hollywood movie ‘The Giant’, starring James Dean & Elizabeth Taylor, stayed during the filming of the movie; photographed by Maryam Eisler, 2024

Windmill sentinels

over the oil field.

The air is quick here.

You can’t keep your

thoughts with you.

The star dome

holds you down

while you move.

The yucca heads higher

than a street sign,

flowers brown and dry,

still hanging on, stalk bent

from day after day of the

troposphere in motion.

Learn surrender from

the yucca. It rattles

before its release.

The land is home

to ore, ice volcanos,

ocean floor turned

high desert, Eileen

the horse that did

not die on the way

to El Paso, you.

Pumpjacks pull.

Windmills spin.

The yucca shudders and

two brown blossoms

light on the wind.

Eileen stretches

her bum leg.

The journey – from photography to poetry – provides, in Carrie Scott’s words ‘a dialogue about the deep humanity embedded in the landscape’s history’. And, indeed, it is ‘a tapestry’ as well as a dialogue, as the Director of Photo London concludes – ‘of beauty, emotion, and storytelling, inviting viewers to contemplate the profound depths of the American big nature experience alongside the quiet poetry of simple existence.’

Here, in Riboud’s street scene in El Paso is what Eisler calls his ‘geometric approach to depicting space in its subtle linearity, very unique to his eye’; photographed by Alexei Riboud, 2024

From dialogue, to tapestry, the works will soon be woven into a book, as well as an exhibition to be launched around Photo London 2025 – and in a way, as Scott aptly notes, ‘that we haven’t seen before’.

See More:

Recent Comments