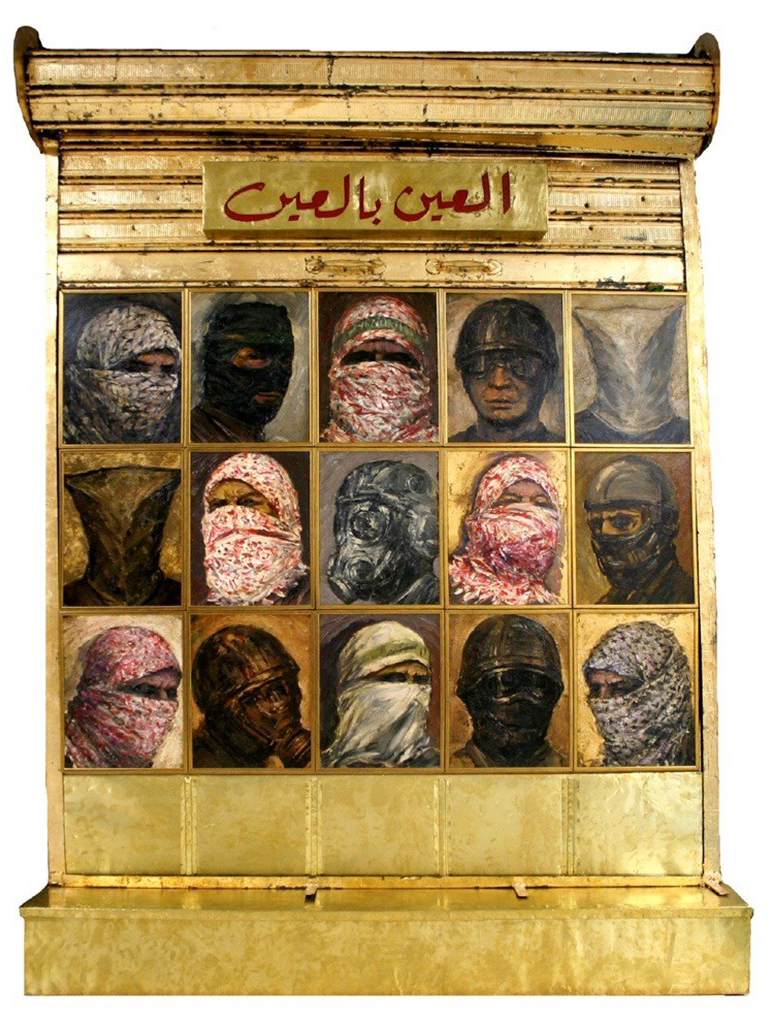

Installation view from Huang Yong Ping’s exhibition ‘Wu Zei’ at Musée océanographique de Monaco (represented by Kamel Mennour)

The art world has been hit harder than most industries by the global pandemic, but the industry is adapting quickly with new digital platforms and a renewed focus on local identities. Nick Hackworth speaks to three leading European galleries, Victoria Miro, Kamel Mennour and SETAREH, about the future and how their businesses are responding

‘It was too much’ is an almost universal sentiment expressed now by those at the top of art world reflecting on pre-Covid times. For those caught up in the global merry-go-round of art fairs, biennales and major openings, the disconnect between the art – the thing-in-itself – and the business and culture around it, was increasing apparent year on year.

The energy and flavour of that now, suddenly distant world is brilliantly captured in the prologue of Boom, Michael Shnayeson’s recently published account of the rise of the contemporary art market. His opening scene is set in the Grand Hotel Les Trois Rois on the eve of Art Basel 2017, where the mega dealers are congregating: ‘Gagosian has flown to Basel on his $60 million Bombardier General Express jet two days before the fair’s first choice VIP preview… Most other dealers would arrive on Monday, a day before the fair’s coveted VIP opening. A few, like silver haired blue chip dealer Bill Acquavella, would arrive in their own planes. Others would descend at Basel’s EuroAirport in NetJets filled with collectors and money, like an art world air force.’

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Basel was, of course, just one of the many stops in a hyper-globalised art world sustained by an increasingly intense circulation of people and product. In a bid to capture as much of that energy as possible the biggest galleries, the likes of Gagosian, Pace and Hauser & Wirth opened spaces across the world, becoming truly global businesses.

Generally speaking, however, art is an object of aesthetic and intellectual contemplation, often revealing more of itself to those willing and able to take the time to look and think – a resource squandered by a culture of constant travel. Then the pandemic hit, the music stopped – cue much soul-searching about the systemic problems in the art world, prime among them, an profound imbalance between the global and local.

Victoria Miro, London & Venice

Founded in 1985, Victoria Miro is one of the most significant contemporary galleries in the world and a foundational presence in the London art scene, representing some 40 international artists and artist estates. The gallery has a boutique space in Venice, and a space in Mayfair, London, but without doubt the gallery’s spiritual home is its extraordinary complex of voluminous spaces designed by Claudio Silvestrin in its building on Wharf Road in East London.

Victoria Miro and gallery partner Glenn Scott Wright in Victoria Miro Mayfair, with artworks by Yayoi Kusama

Artworks courtesy the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro. © YAYOI KUSAMA

Glen Scott Wright: “We don’t see ourselves as specific to a locale. Our artists come from all over the world, they show all over the world, and the world comes to London. I think London is a great place to be for that. In the past, of course, we were able to to engage with specific localities through art fairs. For a while we were doing something like twelve or thirteen fairs a year but obviously that will change now and we’re finding different ways of addressing that global marketplace. The digital marketplace is going to be an increasingly important, of course.

Read more: Meet the winners of Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation’s awards

We recently did a collaborative project with David Zwirner called Side by Side, where we created a micro-site, showing some of the artists that we both work with. We also used the occasion to launch an extended-reality app called Vortic Collect, a project that Ollie, Victoria’s son, has been developing for three years now. On Vortic people can actually enter our spaces virtually and look at art. They can walk around a Grayson Perry sculpture, they can walk up to a Njideka Akunyili Crosby painting and look at it close-up. It’s really very exciting that people can look at exhibitions on their phones or their iPads and have an accurate experience, in terms of being able to see what the art is like.

Victoria Miro, 16 Wharf Road, London N1 7RW. Courtesy Victoria Miro. Photograph © James Morris.

Installation view of THE MOVING MOMENT WHEN I WENT TO THE UNIVERSE

, by Yayoi Kusama, Victoria Miro, Waterside Garden, 16 Wharf Road, London N1 7RW. 3 October – 21 December 2018. Courtesy the artist, Ota Fine Arts and Victoria Miro. © YAYOI KUSAMA

We’ve actually doing well in terms of sales on these digital platforms. We’ve had opened a sell-out show with Flora Yukhnovich on Vortic. The project with David Zwirner was very successful for us as was Frieze New York online. This illustrates an interesting point. I have clients of the old-school variety who’ve been collecting for decades and faithfully go to all the major fairs, biennales and openings. Some of them have written to me and said, ‘Look, we’ve always bought art that we can see, experience and engage with in the gallery, at an art fair, or see in a major exhibition. That’s not going to happen anymore. We’re not travelling. We’ve never bought art digitally, but we still want to buy art! So we’re going to be buying art and looking at digital images for the first time.’ These are several conversations that I’m merging together. But, in essence, the way people engage with art is changing and I think that’s a really interesting paradigm shift.

In terms of what change we would like to see happen in the art world as a result of this crisis, the change of pace is good. I mean, the amount of travelling I was doing! I just looked at first ten weeks of the year in my diary and I was in a different city, at a different opening, at a different event, at a different exhibition every other day. And this is all over the world, from Paris to Asia, to Australia to the States. Literally, just bouncing around all these places. I was recently scrolling through my photos and it was just pictures of planes and airports and different cities and dinners and openings and artists. My life was crazy! So less travel would be great and in terms of global warming it’s good that we’re not shipping things willy-nilly all over the world. Just having a little bit of breathing space has been fantastic.”

Find out more: victoria-miro.com

Kamel Mennour, Paris & London

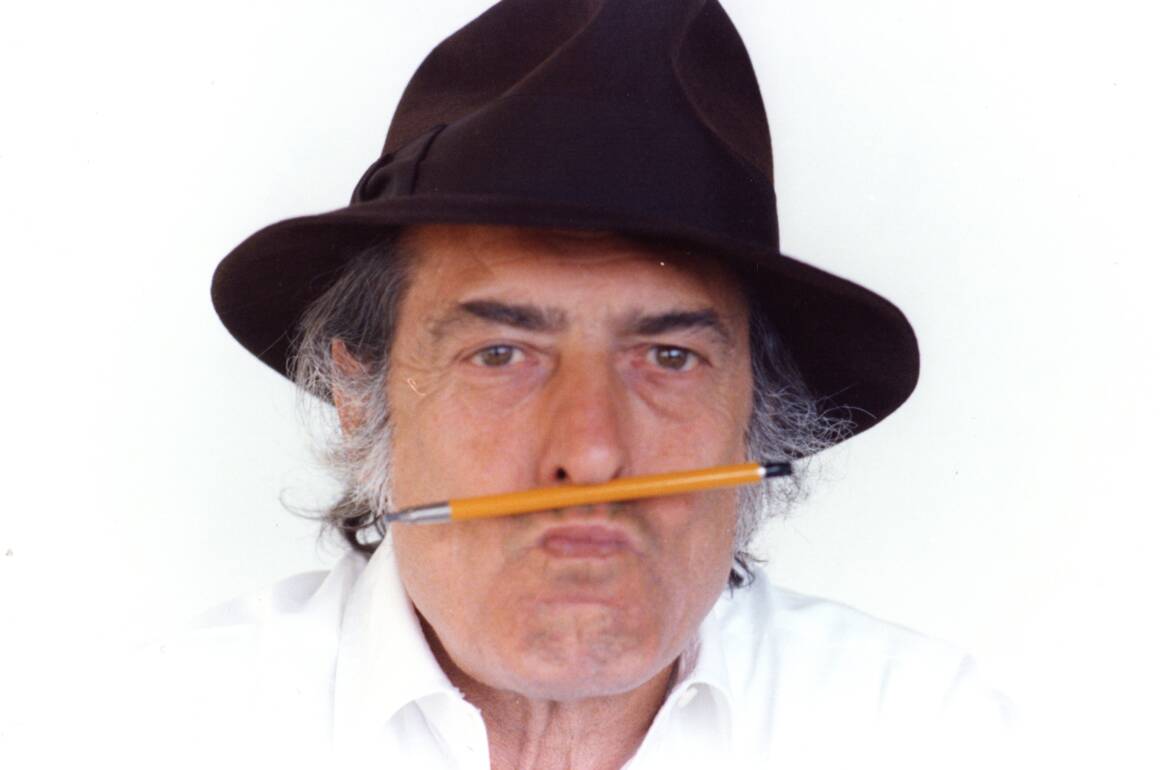

Kamel Mennour

One of the world’s most respected gallerists, Kamel Mennour has been in business for over 20 years. His roster includes some 40 artists, including Tatiana Trouvé, Anish Kapoor, Lee Ufan, Daniel Buren, Douglas Gordon, Philippe Parreno, Martin Parr and Ugo Rondinone. Mennour is known for the quality of his program, going the extra mile to realise the creative ambitions of his artists and for championing his home town of Paris. He has three galleries in the city, two on the left bank and one on the right bank on the prestigious Avenue Matignon, as well as a boutique London space in the Claridge’s building.

Kamel Mennour: “People were often offering me opportunities to open everywhere. Bigger spaces in London, New York or Hong Kong and I was always saying no. I prefer to be extremely stable and to be extremely confident and strong in my city. I decided long ago that being Parisian was in the DNA of the gallery.

Read more: Bentley reveals its sleek new Bentayga model

As you may know, twenty years ago, Paris was totally empty, there was nothing in terms of contemporary art. I was thinking that I could, along with others, help restore Paris’ place in the art world. Also I didn’t want to be the number 38 in New York, you know? In Paris I am one of the key players, the one that the Pompidou Centre or the Palais de Tokyo calls. But of course, in order to expand and promote my artists and the gallery, my strategy is to be ambitious at art fairs like Frieze or Basel, and to stage extremely strong displays that keep the attention of the art world.

Kamel Mennour’s gallery space on Avenue Matignon, Paris

An installation by Tatiana Trouvé at Kamel Mennour’s booth at Frieze London 2018

When we opened the space on Avenue Matignon [on the right bank of Paris], people said, ‘Are you kidding? Why are you opening there?’ The right bank, yes, that’s where the wealthy collectors live, but for contemporary art at that time, it was a desert, a total no man’s land. People are coming there now, but my idea was quite retro. In the thirties and the forties, before the second World War, the right bank was where the centre of Paris’ contemporary art scene, but it collapsed as France collapsed. So I wanted try to do something new and bring something back. I said to myself, instead of opening something weak in New York, I would prefer to be confident and strong in my own city and to be very present. When a collector or the director of a museum wants to see me, I’m here. I can be extremely reactive and I am always taking the subway or an Uber to meet people. I also represent artists from my city. Some of my artists are based in Berlin or New York, but most of them are here and I’m always trying to persuade artists to come and live in Paris.

Now, with lockdown, the world we knew before – with planes and travel – is gone. Now, I’m thinking every day how lucky I was to have had this intuition, to be strong here. I wish them all the best, but it will be extremely difficult for those galleries that have places all over the world to manage in this new world.”

Find out more: kamelmennour.com

SETAREH, Düsseldorf

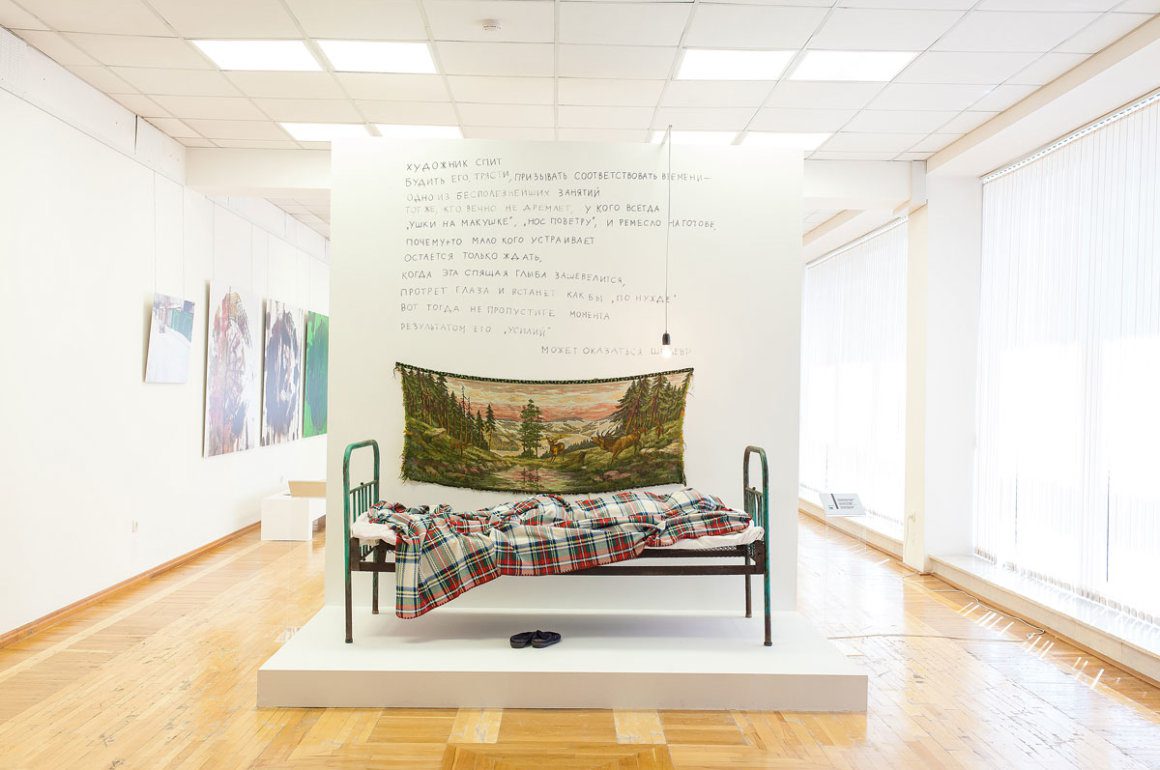

Samandar Setareh

Founded in 2013 by two brothers – Samandar Setareh and Elham Setareh – SETAREH grew out of a third generation family-run business specialising in textile art. That background eventually led them to open the gallery which now has three spaces in Düsseldorf, including two on the city’s grandest avenue, Koenigsallee and one, SETAREH X, that showcases emerging artists. With its broad program of global contemporary art, the gallery has brought a new and vital energy to the venerable Rhineland art scene. Highlights have included shows of new Iranian and Chinese contemporary art, as well museum quality shows of major German art such as Hans Hartung and the Zero group.

Samandar Setareh: “I think this pandemic will have a profound effect on the art world. I already see successful business models being challenged. Galleries that had detached themselves from their artists and their natural collector base and moved into a kind of travelling environment and artificial marketplace are going to find it difficult. Galleries that are are deeply rooted in relation to their collectors and their artists will be the winners of this new time which we are facing. This is an approach we’ve had from the beginning. On starting the gallery, we decided to be deeply rooted in this area and to make that a point of excellence in a sense. We have deep relations with the collectors and collections here, and we’re very close to the institutions of the regions. We have world-class museums in this area, the Ludwig museum in Cologne is very close, the NRW Collection in Düsseldorf and one of the best things is that we have is the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, which has produced perhaps 75% of the very important German artists in the post-war period. So while Düsseldorf isn’t a financial hub compared to places like Paris, London or New York, it’s a cultural production hub.

Read more: Founder of London Art Studies Kate Gordon on digital art history

‘Light and Ceramics’ by Otto Piene at SETAREH Gallery, 2014

Installation view of Zero group exhibition at SETAREH gallery, Düsseldorf

When we started in 2013, the art market was exploding in terms of how international it was becoming. The Rhineland then was still dominated by all big artists, such as Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Joseph Beuys (who all come from the Düsseldorf Academy), the Zero art movement, Markus Lüpertz and Jörg Immendorff and so on. They dominated the way people collected and accepted art. Being from a mixed German and Persian background, one of our missions was to expand and broaden the kind of art that collectors in the region looked at and to make it more diverse, culturally. So we staged the first Italian Modernism art exhibition in Germany, the first contemporary Iranian art show in the region and have showed artists from China and so on. That’s why we also had to have a number of different spaces in the city so that we can show a wide range of art at the same time.”

Find out more: setareh-gallery.com

Nick Hackworth is a writer and curator of Modern Forms, an art collection and curatorial platform founded by Hussam Otaibi, Managing Partner at Floreat Group.

Recent Comments