The Clos de Tart buildings and vineyard rising directly behind the local village

A celebrated winery is acquired by one of the titans of the luxury industry. After a subtle transformation, Clos de Tart emerges with refreshed ancient buildings and upgraded winemaking. Darius Sanai visits François Pinault’s flagship estate in Burgundy. Photography by Martin Morrell

In the heart of the little village of Morey-Saint-Denis in eastern France, next to the old church and across the road from the boulangerie, is a very old, important-looking building with an archway entrance and an arched window set high in the facade, a cross-shaped window above. The village ends at this building, and beyond it are rows of vines, striped laterally across a hillside rising to a forest above.

The cross above the arched window, a reminder of the Cistercian nuns who ran the estate for centuries

This building is the winery of the Clos de Tart, a name close to the hearts of wine lovers, who for centuries have prized the Grand Cru Burgundy red wine made here in the vineyard behind. The vineyard itself is a monopole, an area owned by one single owner, itself a rarity in Burgundy, where patches of land are often split into strips for different owners.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

The Clos as we know it was founded in 1141 by winemaking Cistercian nuns, who ran it until the French Revolution in 1789. Their manual press, carved from wood like a giant olive press, is a highlight of any visit to Clos de Tart. The estate became even more celebrated in 2018, when it was bought by the Pinault family through its holding company, Artémis Domaines. Owners of Château Latour and Christie’s auction house, the Pinaults are also the second most powerful force in the luxury-goods group through a majority ownership of Kering, the group owning Gucci, Saint Laurent, Balenciaga and many other premium brands.

Views of the vineyard

Four years after the estate changed hands, I am sitting with Frédéric Engerer, CEO of Artémis Domaines and the man in charge of all the Pinault’s wine holdings, in an upstairs room in the winery, above a little courtyard, facing the vines. A refurbishment of the winery buildings has just been completed by Paris-based über interiors architect Bruno Moinard.

Details from the refurbishment by Bruno Moinard

The highlight of this gentle revitalisation is a tasting room on the upper floor of the main building, with windows looking out to the vines and trees beyond – a contrast to Burgundian lore that dictates that even the best wines are tasted in a damp, dark cellar with a view only of barrels.

Details at the estate

We are speaking ahead of a little concert planned at the winery that evening, featuring an octuor (octet) of musicians drawn from the Berlin Philharmonic and leading orchestras in France, an elegant celebration of the completion of the works. The Clos de Tart estate is another jewel in the crown of the Pinault family.

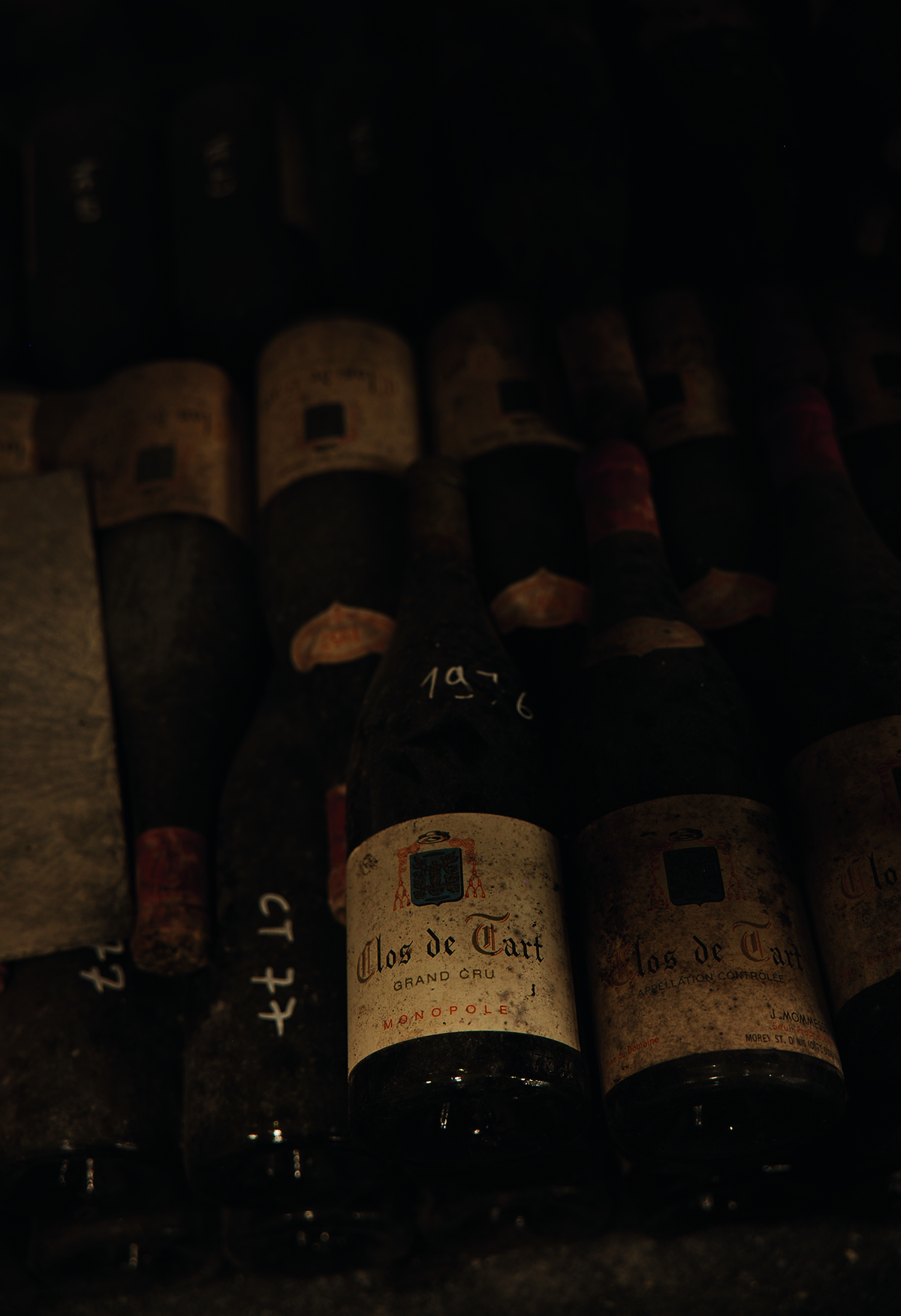

The refreshed cellar, photographed by Isabella Sheherazade Sanai

Quite aside from its holdings in luxury goods and art, its wine group now comprises one of the great estates of Bordeaux, in Château Latour; two Burgundy estates (Clos de Tart and Domaine d’Eugénie), the leading white-wine estate in the Rhône (Château Grillet) and a highly respected champagne house, Jacquesson. What next for Artémis Domaines, I ask?

The vat room containing the precious vats of Clos de Tart’s red Burgundy wine

After a raised eyebrow and a shrug, Engerer offers a little hint. “In Burgundy, we are so happy to be here in Clos de Tart, but we have only red wine with both Burgundy estates, so rebalancing the two colours a bit would be amazing. In the Rhône it is the other way around – only white…”

Views of the vineyard and the restored buildings at Clos de Tart

We should keep tuned for developments, it seems. Lovers of Clos de Tart should be in for a treat because the aim is to make one of Burgundy’s great wines – albeit one that doesn’t achieve the prices and desirability of its most famous labels, like La Tâche or a top Grand Cru Chambertin – even greater. But Engerer also wants to speak about the wine being made now.

Aspects of the revitalised tasting room and Old Press Room

Ever methodical, he first talks about the potential of the raw materials: the grapes grown in the 18.5-acre rectangle that is the Clos de Tart vineyard, just above us. At the foot of the slope, he says, “you have this reddish soil, it’s not very deep and there’s a lot of limestone underneath. And this makes the wines very delicate, very complex.

The tasting room and Old Press Room are a pinnacle of the estate’s elegantly simple renovation

There’s probably more complexity on the north side and a bit more structure on the south side. But even with those north/south differences, you move up the hill and the slope becomes much steeper at mid-point, and then you have deeper soil, and that’s where the sun heats the vines more and gives you a style that is richer, deeper, generally ripening a little bit earlier, with more muscle. And the muscle is even stronger when you go south than when you go north.”

Modernisation of the historic interiors by Bruno Moinard,

If that all sounds a little mind-boggling, it is, and Clos de Tart’s new guardians are in the process of working out just what potential they are sitting on. Engerer says a key development in the revived winery is the ability to make wines from small individual parcels of vines in the different positions in the vineyard, all the better to judge the balance of the final blend.

Viewpoints of the historic interiors, refurbished by Bruno Moinard

For the wine lover, the difference is in the tasting. Clos de Tart has always been a great Burgundy. But that evening, after the magical concert and as a sunny evening turned into a deep blue night, guests tasted some of the great vintages of the past, including 1990 and 2005.

A selection of vintages of Clos de Tart Grand Cru wines

We were also given a tasting of the first vintage made by Engerer’s team, headed by winemaker Alessandro Noli: the 2019. Just three years old, this should have been shy and immature compared to the past greats, but it just seemed like a more layered, more precise, more delineated and more delicious progression of the same elements.

Read more: A Tasting of the World’s Greatest Champagne Houses

Apparently, as the team understands the natural resources they have on their hands more with each year, things will only get better. In the meantime, we are more than happy to settle for a few cases of the 2019, ideally sipped over a rendition of Mendelssohn by eight talented musicians from the Octuor Éphémère, with the slopes of the Clos de Tart as a background.

Find out more: www.clos-de-tart.com

This article first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2022/23 issue of LUX

Recent Comments