The reception at Preventicum’s London clinic

London’s Preventicum has been at the forefront of preventative healthcare – where you see and anticipate potential health risks – for almost two decades. Here, Preventicum’s Medical Director, Dr Ying-Young Hui speaks to Samantha Welsh about how about the importance of early detection, and how a holistic approach can give a complete picture of health, guiding on lifestyle changes and potential clinical interventions; and we present some frankly chilling case studies

LUX: What brought about Preventicum’s early start in the competitive health diagnostic space?

Dr Ying-Young Hui: Preventicum launched its pioneering preventive health assessments in London in 2005 at its luxury London clinic. We developed our detailed health assessments to give clients the ultimate reassurance and peace of mind, enabling them to live their lives to the full. Instead of addressing health concerns when they arise, we can detect the earliest signs of and risk factors for heart disease, cancers, stroke, diabetes and many other conditions. This proactive approach allows us to create tailored health and lifestyle plans so that our clients can stay in optimal health and well-being.

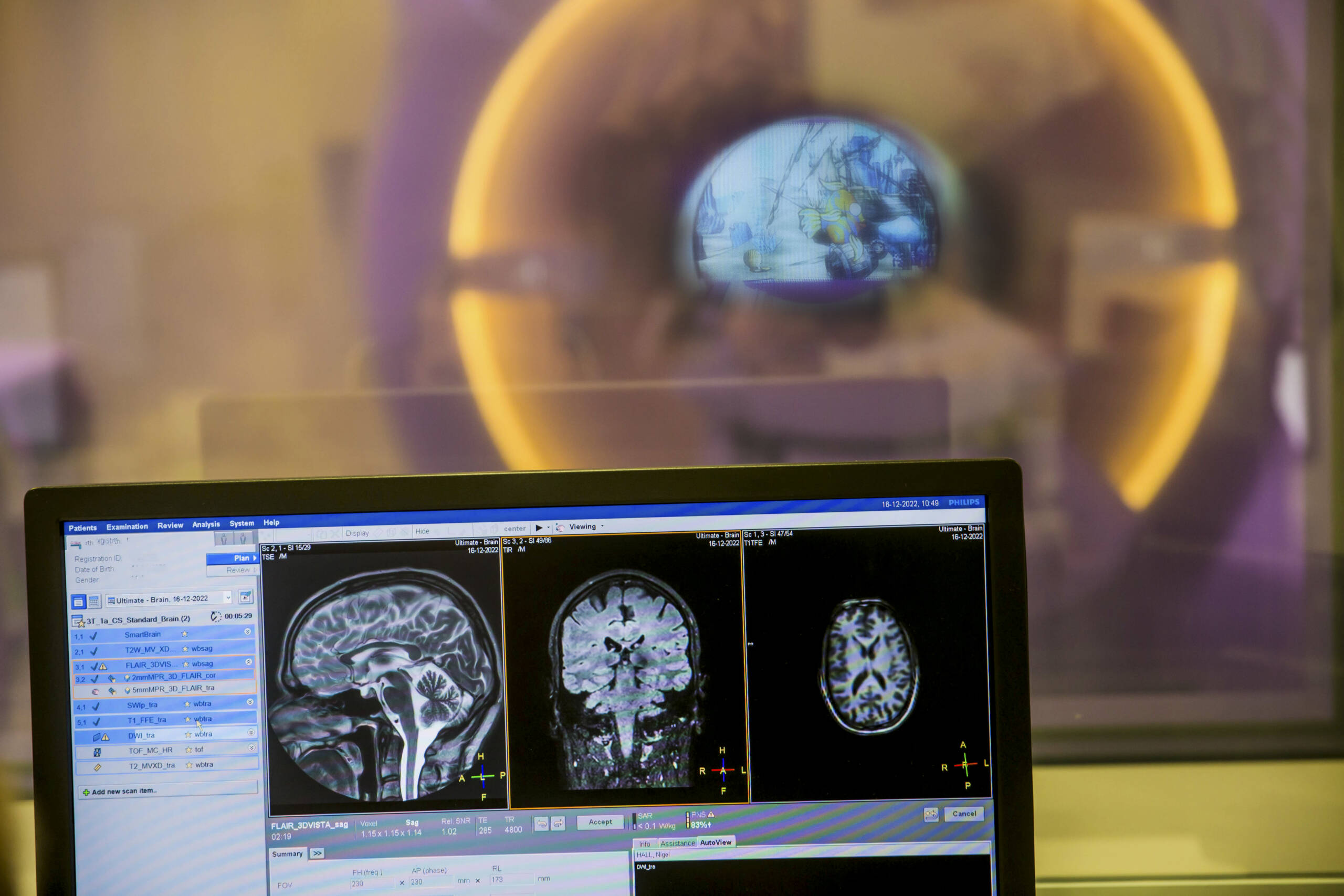

Preventicum offers preventive healthcare, using state of the art technology

LUX: What breakthroughs differentiate Preventicum services from those of competitors?

Dr Y-YH: For over 19 years, Preventicum has been at the forefront of preventive health and we have developed the most advanced and safest health assessments in the world. We combine pioneering cardiac and brain analysis, laboratory tests, state-of-the-art, radiation-free MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and ultrasound scans with detailed GP and Radiologist consultations, as well as referrals to a network of specialists.

Read more: How art is remediating environmental and societal damage from overdevelopment

Preventicum offers the only doctor-led, non-invasive health assessments that are completed on a single day, under one roof, with results available before our clients leave. By consistently researching and introducing new clinical developments, we ensure that Preventicum remains at the forefront of preventive healthcare, offering our clients the very latest, gold-standard tests and technology.

LUX: With the curated approach to the hospitality experience, what does this show about values and clienteling?

Dr Y-YH: At Preventicum, our clients’ experience extends well beyond the medical tests and scans included in their health assessment. Many of our clients describe their experience as “spa-like” thanks to our beautiful environment and our dedicated team who provide unparalleled service and build long-lasting relationships.

Dr Ying-Young Hui, Preventicum’s Medical Director

With a tailored approach, our client’s Preventicum Doctor oversees the tests and scans that are included in their health assessment and along with two detailed consultations, they create a detailed clinical report and lifestyle prescription

LUX: How do you structure the detailed client consultations at the beginning and end of the day?

Dr Y-YH: Each client meets a dedicated Preventicum Doctor who guides them through their assessment and addresses any health concerns. The day begins with up to an hour with their doctor to discuss their current health, medical and family history and any specific concerns they may have. We also assess key lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, alcohol intake and sleep, all which are crucial in determining current health and future risks. This consultation also includes a comprehensive physical examination and a guide as to what will happen throughout the day.

Following the client’s tests, MRI and ultrasound scans, and cardiac assessment, clients have a unique opportunity to review their MRI scans in a consultation with one of our Consultant Radiologists, including viewing their beating heart. The day concludes with a consultation with the client’s Preventicum Doctor to discuss the day’s findings and results, provide reassurance and where clinically indicated, arrange referrals to specialists within our network.

‘Preventicum remains at the forefront of preventive healthcare, offering our clients the very latest, gold-standard tests and technology’ – Dr Ying-Young Hui

LUX: Lifestyles in the developed world are contributing to rising rates of diverse cancers. Where have you had successes in early detection, and how can we help ourselves?

Dr Y-YH: Cancer rates are increasing, including in the younger population, with approximately 375,000 new cancer diagnoses per year in the UK. It is estimated that 1 in 2 people in the UK currently under 65 years old will be diagnosed with some form of cancer during their lifetime. Our doctors are able to detect the earliest stages of cancers thanks to the combination of their expertise and our technology.

Recently, we have found clients who showed early stages of kidney, lung, thyroid and prostate cancer. Detecting and diagnosing these cancers at an early stage usually means shorter and less invasive treatment plan and most cancers have far higher survival rates if found early.

To reduce the risk of cancer, we recommend lifestyle changes such as stopping smoking, reducing alcohol intake, increasing physical activity and maintaining a healthy diet. Annual Preventicum health assessments also play a crucial role in identifying signs of and risk factors for cancers, further aiding early detection and prevention.

‘Each client meets a dedicated Preventicum Doctor who guides them through their assessment and addresses any health concerns’ – Dr Ying-Young Hui

LUX: What is the approach to cholesterol management?

Dr Y-YH: Cholesterol management is crucial for a long and healthy life with a reduced risk of cardiovascular diseases including heart disease and stroke. Effective cholesterol management requires a multifaceted approach, combining lifestyle changes with medication and regular monitoring.

Follow LUX on Instagram: @luxthemagazine

During the client’s initial consultation, we spend up to an hour gathering vital information about their lifestyle, personal medical history, family history and any symptoms. This data, along with results from detailed blood tests, blood pressure, stress echocardiograms, cardiac MRI, oxygenation-sensitive cardiac MRI (OS-CMR) and carotid artery ultrasound allows us to create a personalised cholesterol management programme.

We provide specific and tailored advice about changes which can improve High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and lower Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, such as reducing the consumption of saturated fats, increasing consumption of foods high in omega-3- fatty acids (such as oily fish and avocado), setting targets for moderate and high intensity exercise and optimising sleep quantity and quality.

Our approach emphasises reducing future risk with dietary changes, regular physical activity and when necessary, the use of cholesterol-lowering medications, with referrals to lipid specialists when clinically indicated.

Client room at Preventicum

LUX: Hereditary conditions can be the ‘silent killer’, what is your experience with investigation and proactive intervention?

Dr Y-YH: Hereditary conditions often develop without symptoms until they reach an advanced stage, making early detection and regular health assessments even more important. At Preventicum, clients complete a detailed medical questionnaire that includes a full family history, discussed during their hour-long initial consultation. Our Preventicum Doctors oversee all test and scan results and therefore have a complete view of our client’s health.

This proactive approach has allowed us to identify conditions such as cardiomyopathies, heart valve anomalies, and familial hypercholesterolemia early, leading to timely interventions that reduce the risk of severe health issues. Over the past 19 years, we have successfully identified and managed these hereditary conditions in many clients. We also have a partnership with an expert Clinical Geneticist who we can refer to if clinically indicated.

LUX: What other diagnostic areas offer opportunities for innovations in partnership?

Dr Y-YH: Preventicum is committed to remaining at the forefront of preventive health by partnering with leaders and experts in many clinical specialisms. We have worked with Perspectum to offer LiverMultiScan, which provides a comprehensive view of liver health, including detailed measures of inflammation and fibrosis.

Read more: Louis Roederer Photography Prize for Sustainability

In 2023, we introduced our Optimal assessment, the world’s most clinically advanced health assessment, featuring partnerships with BrainKey for detailed brain analysis of over 25 regions of the brain including brain age and Area19 for a world first in health screening – pioneering Oxygenation-Sensitive Cardiac MRI (OS-CMR). Additionally, our collaboration with Medical iSight allows clients to interact with 3D Augmented Reality visuals of their brain scans using Microsoft HoloLens.

LUX: Can some investigations be unnecessarily invasive for the client, for example, cardiac diagnostics?

Dr Y-YH: All Preventicum assessments are safe and non-invasive. Our innovative OS-CMR technology, the most advanced cardiac assessment in the world, is non-invasive and requires no stress or medication. We rely on radiation-free MRI and ultrasound imaging, ensuring our clients avoid any adverse side effects and are not exposed to potentially harmful radiation.

‘Many of our clients describe their experience as “spa-like”’ – Dr Ying-Young Hui

This approach makes our assessments suitable for annual health screenings and also demonstrates our commitment to delivering the most advanced health assessments in the safest and most comfortable way for our clients.

Case studies: Some chilling real life case studies of lives saved and lifestyles altered from the Preventicum team.

High-grade atrioventricular block

A female client in her mid-fifties booked a Preventicum assessment after experiencing shortness of breath climbing stairs and was anxious about her health. During both the exercise stress echocardiogram and cardiac MRI scans, abnormalities were seen. Urgently referred to see a Cardiologist by her Preventicum Doctor. Further investigation revealed a high-grade atrioventricular block and a pacemaker was successfully fitted. Our client reported an upturn in her health and general wellbeing after this procedure.

Large aortic aneurysm

A healthy Orthopaedic surgeon in his late sixties booked a Preventicum assessment. He was known to have high blood pressure. During our client’s ultrasound scan, a 7cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (ballooning of the major artery running down the centre of the abdomen) was seen which had a high risk of rupturing. He was immediately referred to see a Vascular Surgeon who performed an urgent repair to the aneurysm through the main artery of his leg. Normally, large aortic aneurysms remain undetected with sudden death being the first symptom. Five years on, our client is doing very well, having made a good recovery with follow-up monitoring revealing the aneurysm to be fully repaired.

Lung cancer

A 61-year-old Company Director, returned to Preventicum for his third assessment. He was fit and well, living an active and busy life. The Consultant Cardiac Radiologist saw a 6mm lung nodule in the background of the cardiac MRI scans. The client was urgently referred for a follow-up CT scan. He attended an appointment with a specialist who made the decision to watch this for three months.

During this time, the nodule grew from 6mm to 12mm. A specialist biopsy operation at St. Batholomew’s Hospital then confirmed this was lung cancer. An operation at The Royal Brompton followed where 55% of his lung was removed. He was active straight after his operation and within three months was back to riding a bike, playing golf and running at 80% of his previous fitness.

A radiologist consultation at Preventicum

Severe heart disease

A male client in his early seventies visited Preventicum for a third time. All his cardiac investigations were normal and he was generally in good health, but experiencing shortness of breath during bursts of intense activity. Our client’s resting ECG showed severe heart rhythm abnormalities and a further resting echocardiogram showed a dilated left ventricle with poor cardiac efficiency and function.

This was confirmed in his cardiac MRI and indicated the possibility of dilated cardiomyopathy. We referred our client for review with a Consultant Cardiologist and he had an urgent coronary angiogram. He is now under ongoing specialist care.

Kidney cancer

A 54-year-old Finance Director booked his first Preventicum assessment, feeling in generally good health with no specific concerns to address. During his abdominal ultrasound and MRI scans, a suspicious kidney lesion was seen. Following a comprehensive discussion he was referred to a Consultant Urologist for further investigation. Under the expert care of this specialist, a malignant kidney tumour was diagnosed. He had a successful operation to remove the tumour and thanks to our very early detection, he has not needed any further treatment as the surgery was wholly curative.

Large brain aneurysm with no symptoms

A Property Director in his early forties, booked a Preventicum assessment. He had no symptoms and was generally in good health. During his MRI scans, a large 11mm brain aneurysm was seen. The Preventicum Doctor immediately referred him to a leading Neurosurgeon who performed a catheter angiogram to examine the anatomy of the aneurysm in more detail.

Read more: Cristal evening with Louis Roederer’s Frédéric Rouzaud

Interestingly, the year before his visit to Preventicum our client saw a Neurologist who had carried out an MRI brain scan, but the aneurysm had not been seen. The possibilities for intervention were thoroughly discussed and he opted for open surgery to the aneurysm which was a great success.

Coronary artery disease

A client attended his Preventicum assessment and mentioned a four-week history of chest pain during exertion. During his assessment, he was found to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol and a significantly abnormal ECG. The client was urgently referred to a Cardiologist who performed a cardiac CT, revealing a dangerous blockage in the main artery taking blood to his heart.

Following immediate admission into hospital, our client underwent an emergency primary angioplasty procedure to open the blockage and two stents were put into his main coronary artery. He made an excellent recovery and was put on long-term medications to control his blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Prior to his Preventicum assessment, the client had a very high risk of having a sudden, fatal heart attack.

Thyroid cancer

A 28-year-old male client booked his first Preventicum assessment as he was concerned about his general wellbeing, was feeling tired and had been experiencing night sweats. During his assessment, our client’s full blood count and inflammatory markers were normal. However, during his ultrasound examination, our sonographer noted an abnormal looking lymph node in his neck.

An urgent referral was made to a Head and Neck Consultant and following a lymph node biopsy, the client was diagnosed with a medullary carcinoma (cancer) of the thyroid gland. He had surgery to remove the thyroid gland and 50 additional lymph nodes. The client has fully recovered from this curative surgery.

Recent Comments