Sunset, a limited edition photograph by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler

Following in the footsteps of Richard Avedon, Irving Penn and Peter Beard, Cathleen Naundorf is a world renowned photographer who works with large format analogue cameras to create a unique painterly aesthetic. Photographer and LUX Contributing Editor Maryam Eisler speaks to the Paris-based artist about photographing the Dalai Lama, creative influences and developing her own style

Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of the artist

Maryam Eisler: Cathleen, you have been working with analogue and large format cameras for some years now. I am interested in your visual aesthetics, especially in what you call your ‘Fresco’ imagery, which sits somewhere between photography and painting, in my opinion.

Cathleen Naundorf: Yes, that is correct indeed. The technique achieves painterly photographs. As a kid, at the age of four, I already had a pencil in my hand; I drew all my life. I was sponsored very early on, and had my first painting atelier at the age of twelve. It was only later that I decided to become a photographer, because I was looking for something that would allow me to both travel and remain close to painting, at the same time. I was young and didn’t want to be isolated in a studio, I wanted to go out and explore the world.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

I was raised in East Germany, and moved out before the wall was taken down; it was very difficult to get out. At the time, I was desperate to travel, and so, I applied for jobs with book editors and printed media. I landed my first job very early on, at the age of 23, for which I had to do a reportage on the Dalai Lama. By luck, I became a travel photographer, and I fell in love with this medium.

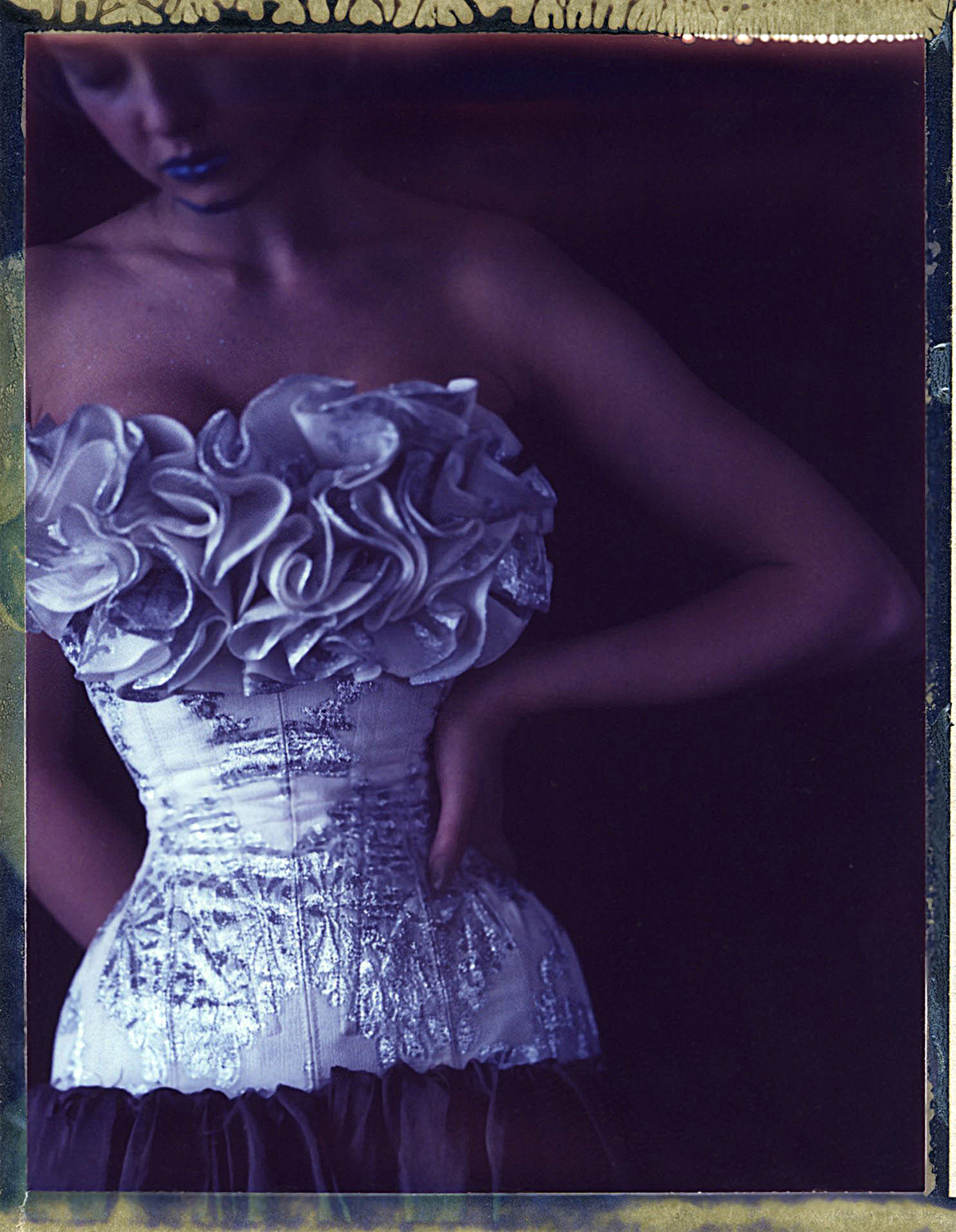

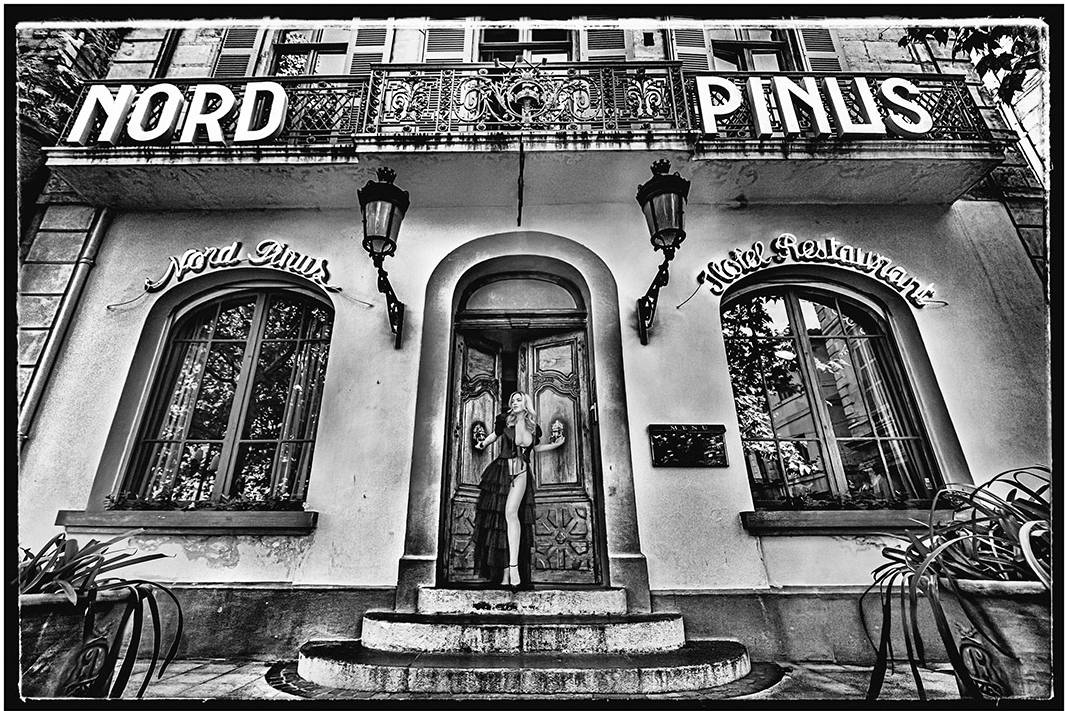

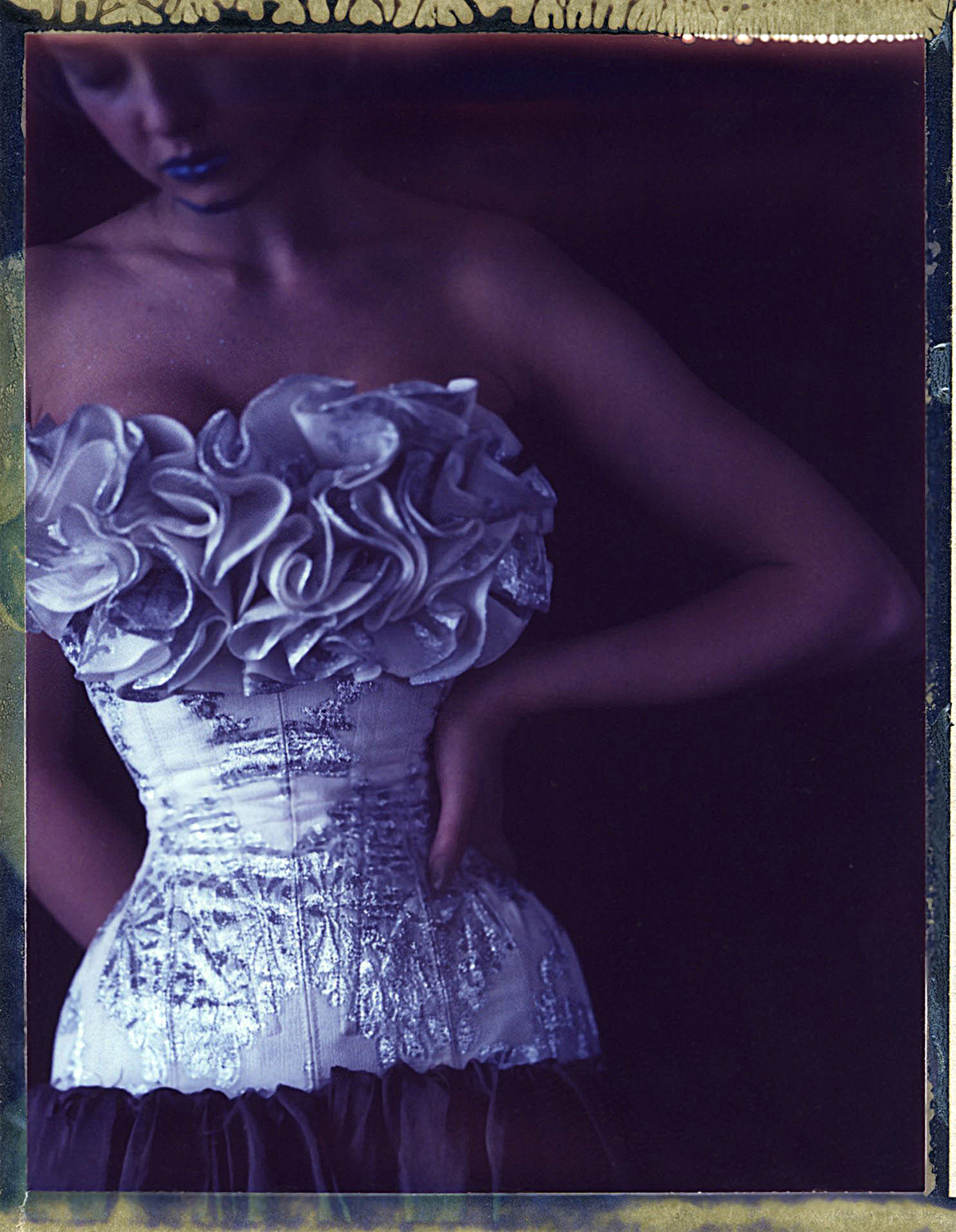

Corset by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Cathleen on a studio shoot. Courtesy of the artist

To go back to your ‘Fresco’ question and achieving that painterly look, I decided to work with polaroid because you see the result immediately. Many 70s photographers also used polaroids as it was a great way to check up on lighting during the photo sessions. Helmut Newton used the XS – 70 polaroids, for example. I used small format polaroids during my travels, and took polaroid portraits of the people I photographed, in order to retain an immediate memory of them. From 2003, I started working in studios and so I chose the professional 8 x 10 inch and the 4 x 5 inch polaroid sheets. There were two reasons behind my choice of this particular material. Firstly, it allows for the development of unique pieces, and secondly, it captures the light in a painterly way. In 2006, I started with the ‘Fresco’ technique, a complicated process, but well worth the complication as it produces stunning results!

Read more: ‘Confined Artists Free Spirits’ – Maryam Eisler’s lockdown portrait series

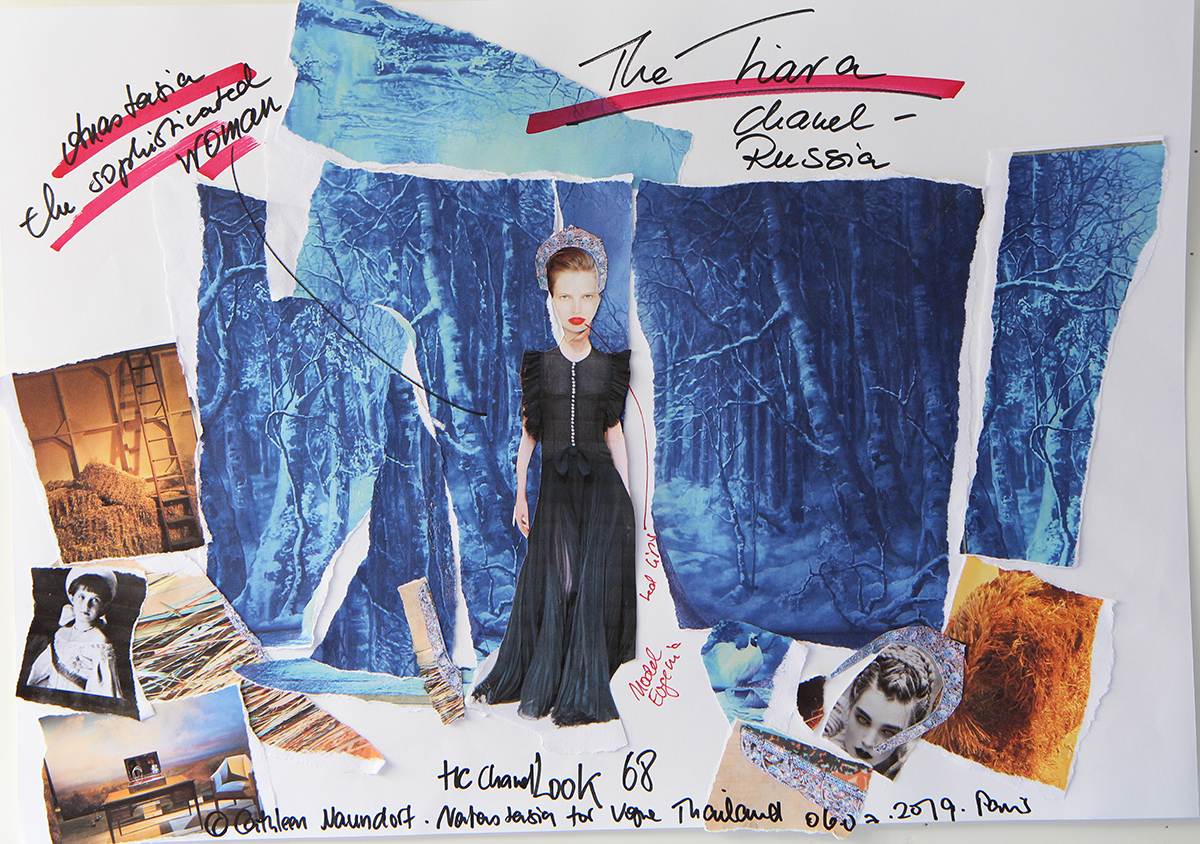

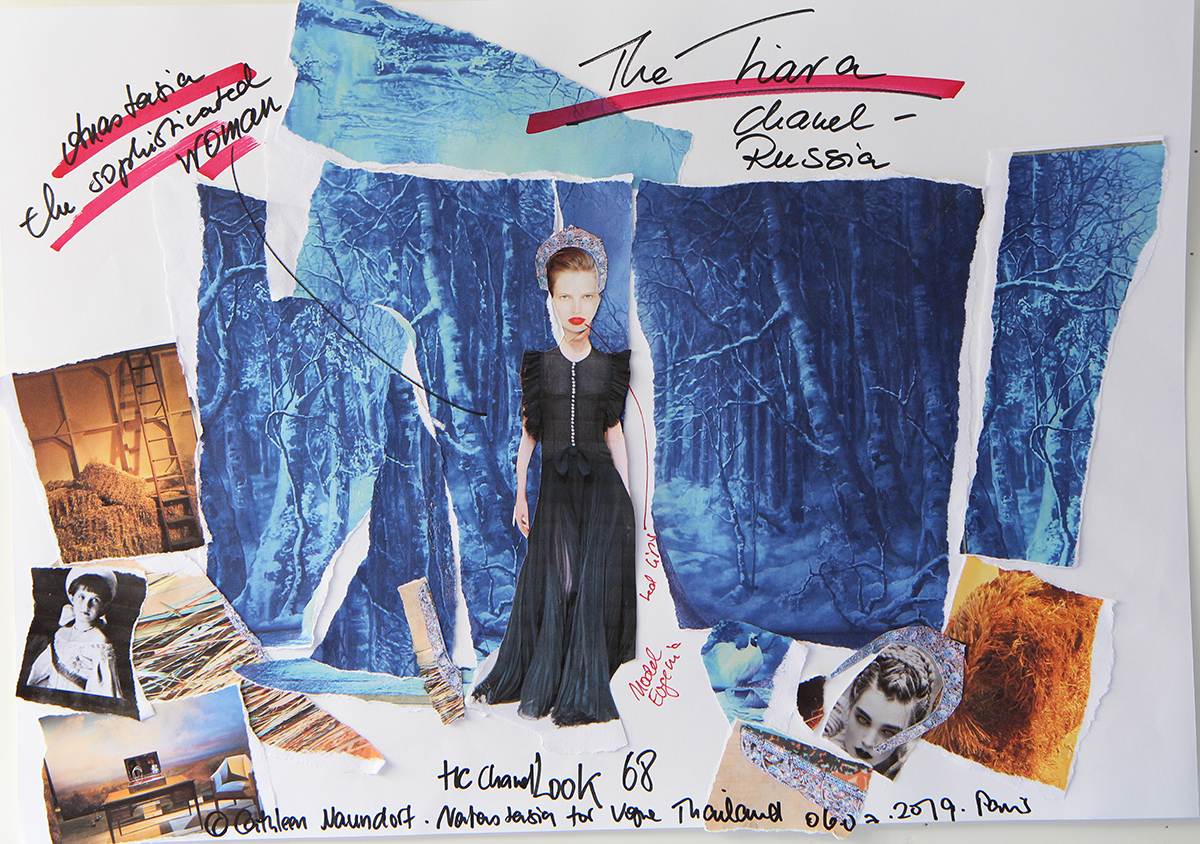

One of Cathleen’s storyboards for Anastasia, Vogue Thailand. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler: I imagine this technique requires everything to be pre–planned?

Cathleen Naundorf: If you work with large format cameras and settings, you have to prepare the photo production well in advance. I draw everything first, each shot, just like you would if you were producing a movie. My storyboards explain the narrative which I have in mind. Each sitter (client or model) receives the story board several days before the shoot so as to get “in the mood”. My team also gets briefed in advance, and as such, all is well prepared. So, once you’re on set, the atmosphere is relaxed, giving time and space to concentrate on the subject, whilst allowing me to pull the trigger at the right moment … the extra ‘wow’ factor!

Read more: British-Iranian artist darvish Fakhr on the alchemy of art

Maryam Eisler: So storytelling is a significant part of your process?

Cathleen Naundorf: It’s always about storytelling. As mentioned, I started as a reportage photographer. When I worked with big agencies, they would always tell me ‘one picture needs to say it all’. I first put this theory to the test when I photographed the Dalai Lama, once when I was 24 and the second time at the age of 26. I think a photograph should always tell a story – this also applies to fashion photography, at least in my case.

Magic Garden, III ,Valentino Garavani, Wideville by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler: Would you say that your collaboration with your sitter equally becomes an integral part of the process?

Cathleen Naundorf: I always ask the person if he or she has agreed to be photographed. It’s a question of respect. Some situations are also very intimate, and the sitter needs to feel more comfortable than usual. With culturally diverse ethnic groups, especially, you need to take time, explain, share with them the process and the purpose of your work. It is a question of trust and communication. With models, they may find themselves nude in front of you. As such, you need to develop trust, respect and comfort, in the rapport which you establish with them. As a photographer, you have to have the ability to open the sitter’s soul, and in turn, they need to be made aware of that. That’s when you bring the best out of people.

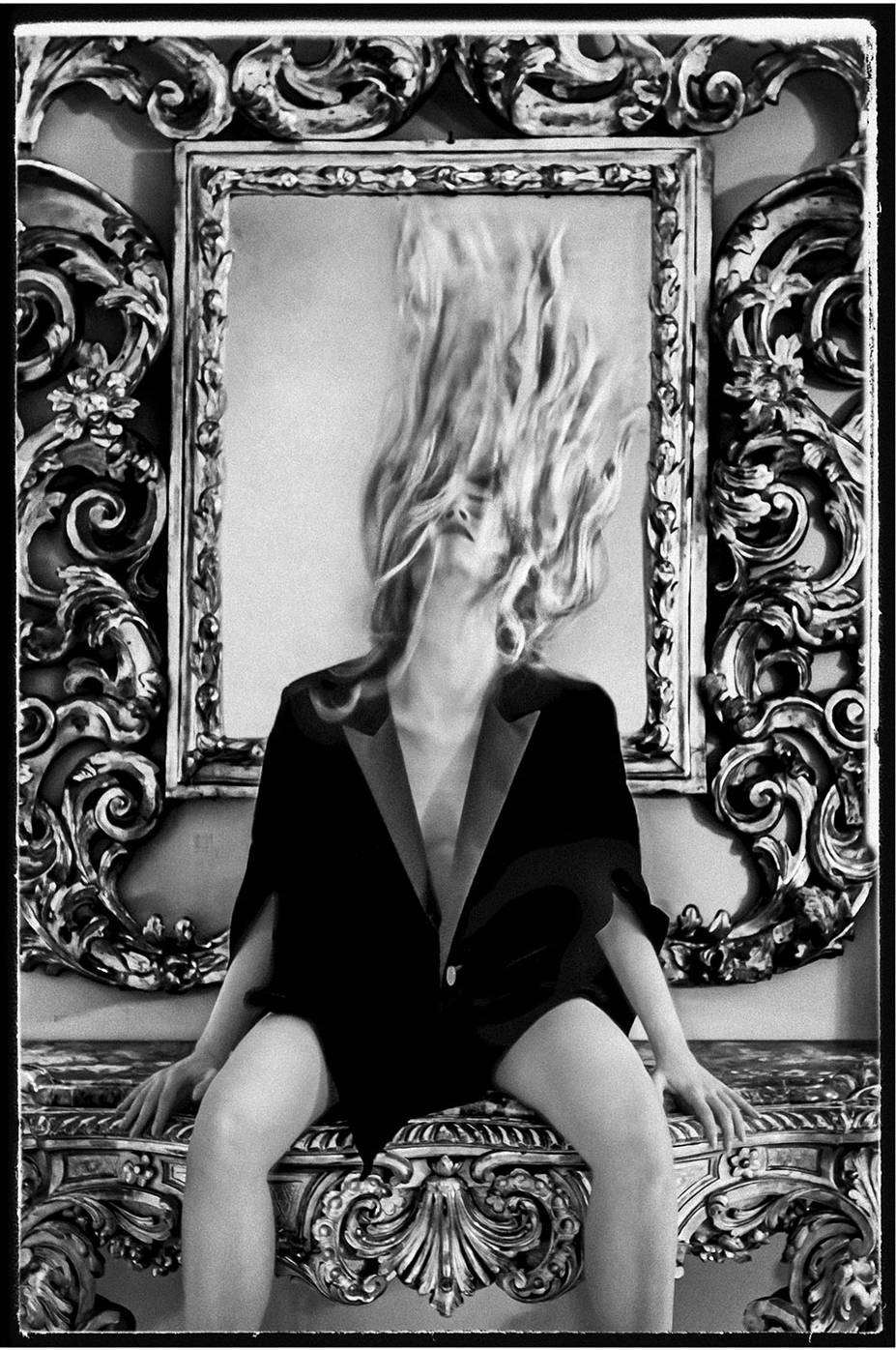

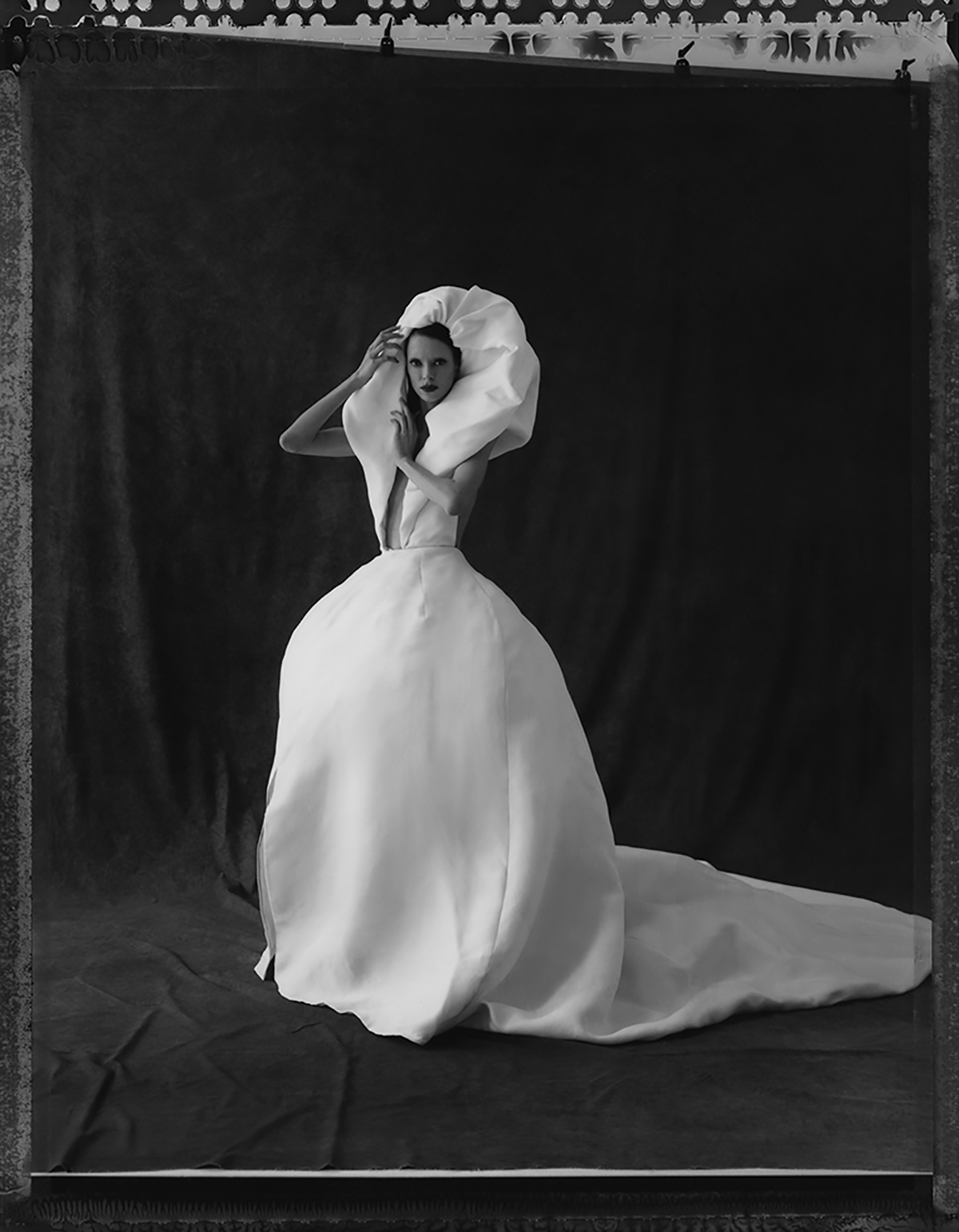

Pose enchantée by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler: Do you have a secret formula or recipe in your photography? A signature of some sort?

Cathleen Naundorf: Not really. I am very critical of myself and try to improve the quality of my work with every shoot. It’s a daily task, step by step.

Read more: A new retrospective of photography by Terry O’Neill opens in Gstaad

Maryam Eisler: Most artists are doubters. They never know when the painting is finished. It is quite wonderful to have that certitude and to be able to say, ‘This is done! This is it!’

Cathleen Naundorf: Yes. When I shoot, I say to the team, ‘Guys that is it; we have it!’ It’s also fantastic to have the polaroid result in 60 seconds. Once I had to shoot the cover for a US magazine and I was photographing Laetitia Casta. I only shot seven polaroids and sent just ‘the one’ to the Editor-in-Chief of the magazine. They complained and asked to see more options, but I knew that that was the one. The magazines sold out, and there was the proof in the pudding! When you have it, you have it!

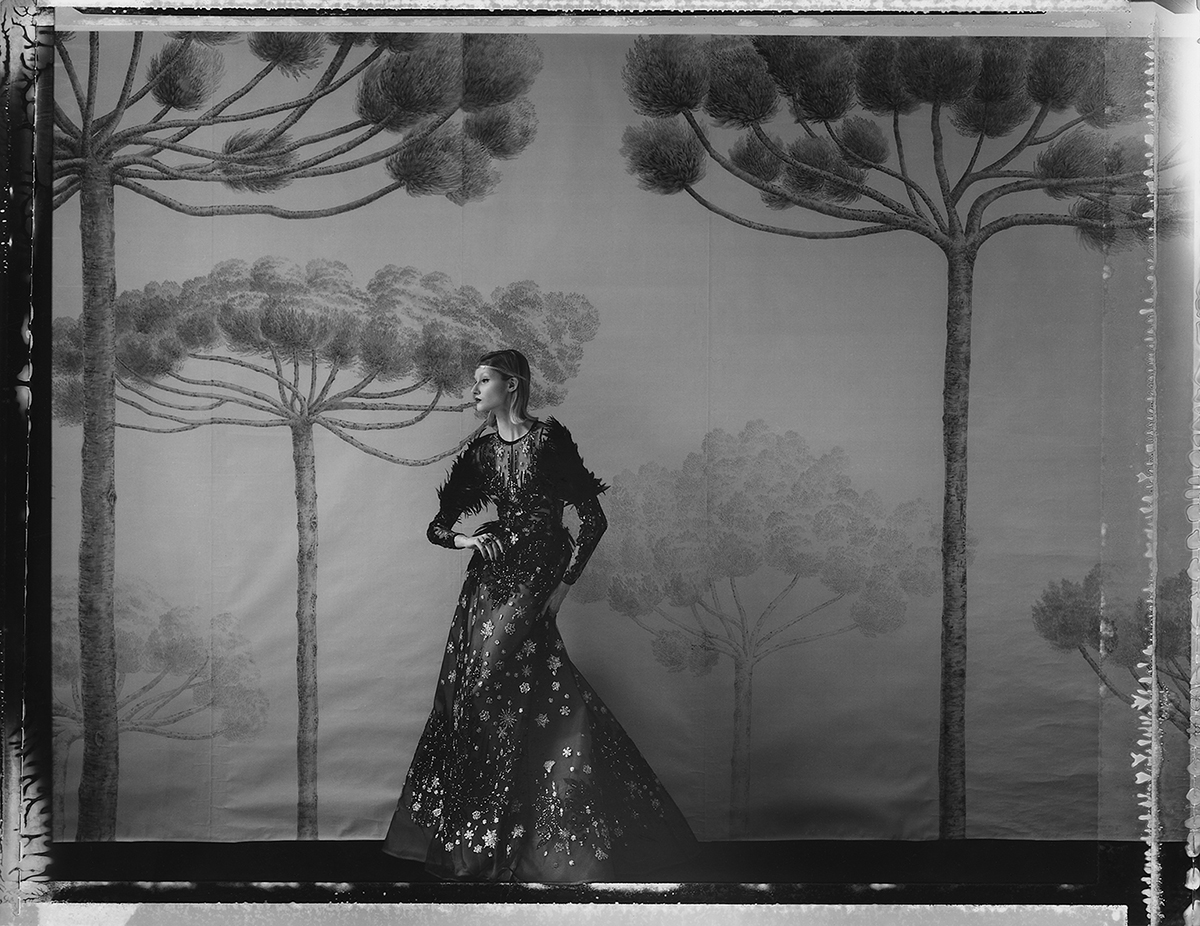

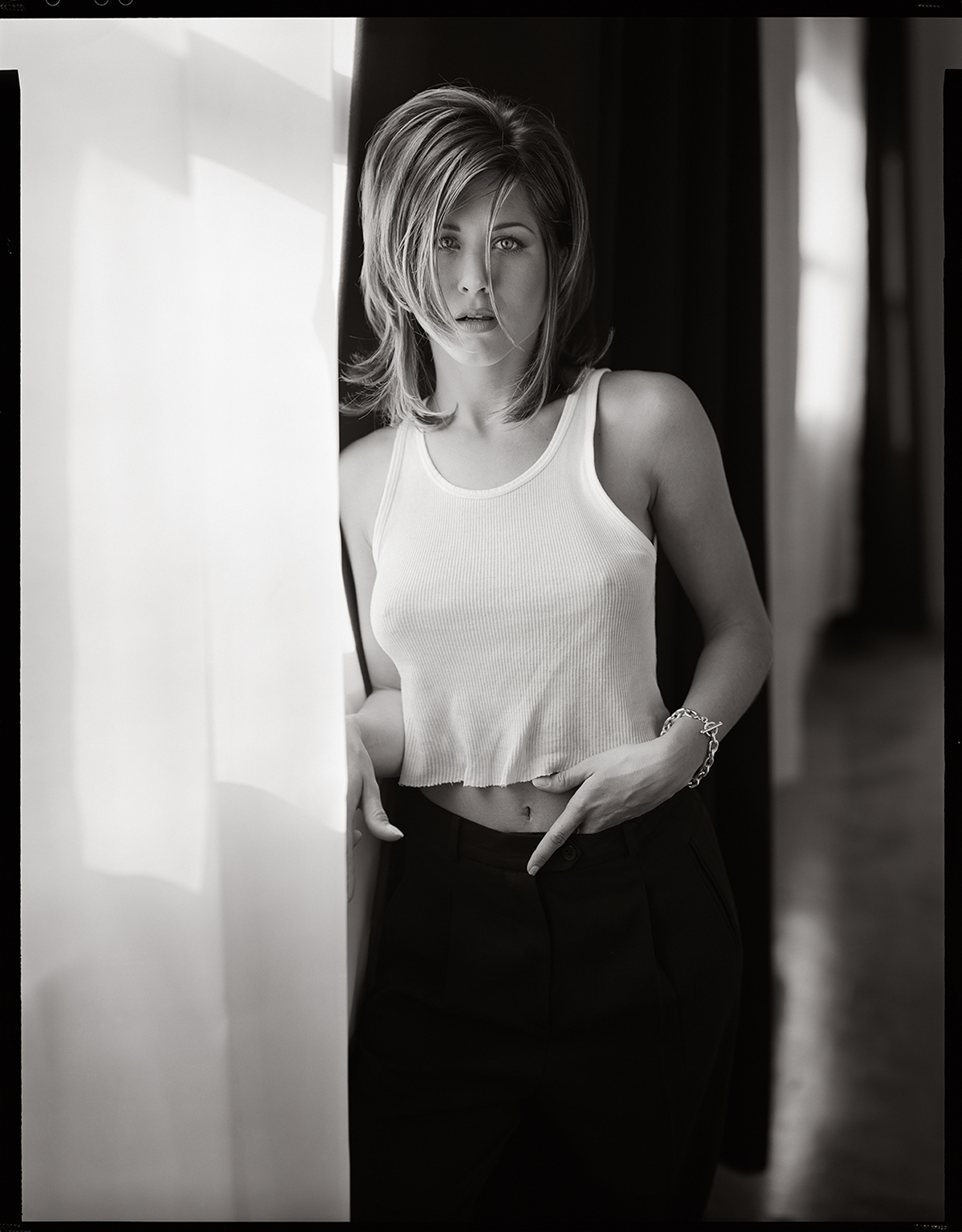

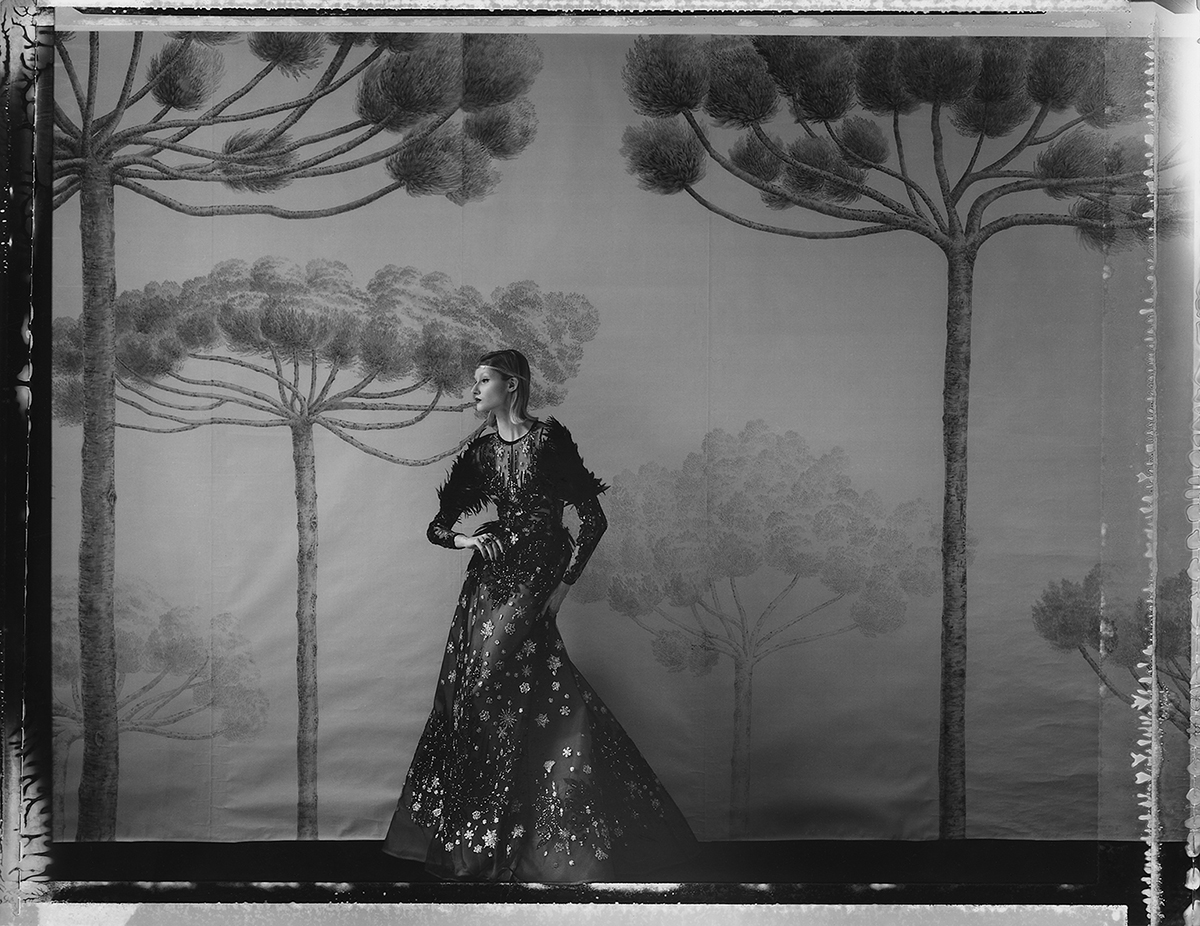

The enchanted forest I by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

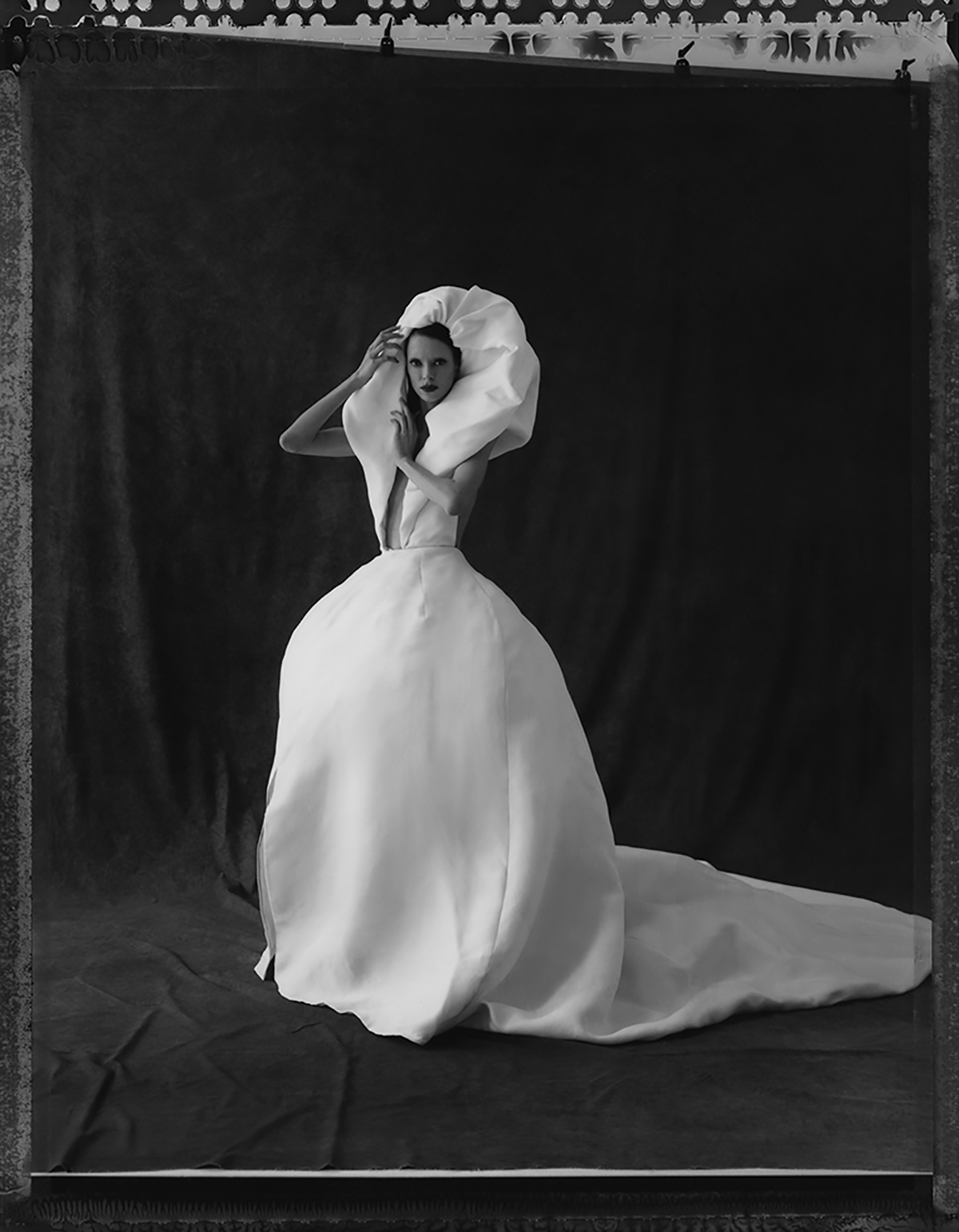

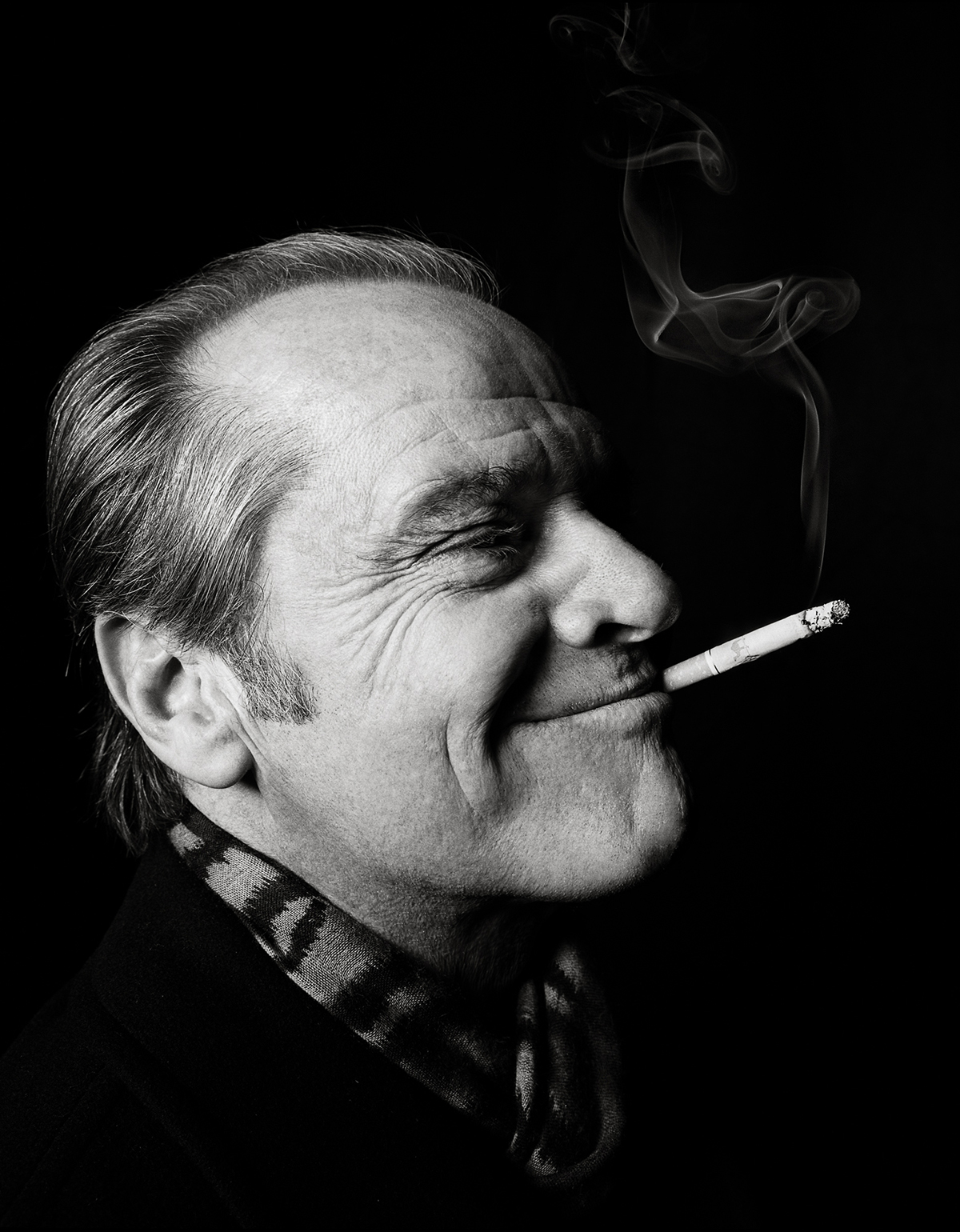

The doubt by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler: How old were you when you left East Germany? And how much of an influence did your country of origin have on your career?

Cathleen Naundorf: I was 17 when I left East Germany. When I was 6 years old, people around me used to say ‘Oh she is an artist, she is so sensitive’. I knew then that I was different. Being raised under that regime made me very strong over the years. Freedom and human rights took top priority in my life as a result. To be physically and mentally free are essential to me. You need to make choices in life and stand for what you believe in. I had to pack my suitcase in 24 hours and take what I could. That teaches you a lot in life!

Maryam Eisler: The choice of photojournalism could be considered activism in itself.

Cathleen Naundorf: Yes, I wanted to give something back to society. At 18, I became an active member of Amnesty International. I worked on cases in Yugoslavia during the war and also in Turkey. In 1993, I met the Dalai Lama. I was very fortunate. As mentioned before, I did a reportage twice on him. I was the youngest photo reporter and I was also the only woman. It was, and still is hard for a woman to be in photojournalism. In East Germany where I grew up, women and men were really equal. So, when I came to the West, I was disappointed. I felt like I had to battle even more in order to gain respect. Even today, I sometimes feel like I have to battle in order to protect my rights and justify my job.

Read more: SKIN co-founder Lauren Lozano Ziol on creating inspiring homes

Maryam Eisler: How do you marry your two worlds together: activism and fashion? It seems like they would normally be at polar opposites of each other?

Cathleen Naundorf: Honestly, I never saw myself as a fashion photographer. Horst [P.Horst] became my mentor and influenced me in the direction of fashion photography at the beginning of my career, alongside the influences of work by Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. I was eventually taken under Tim Jefferies’ wing (Director of Hamiltons Gallery, Mayfair), and the rest is history! When I moved to Paris in 1998, fashion was a kind of ethnic voodoo, with a touch of glamour, especially during the times of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano. It was great and I saw eye to eye with that kind of fashion. But those times are over, there is no Diana Vreeland or Francesca Sozzani anymore. People think I belong to the fashion bunch, but I don’t really. I am considered an artist, even by the fashion industry, and I always want to keep it that way.

In the clouds, II by Cathleen Naundorf. Courtesy of Cathleen Naundorf studio

Maryam Eisler: Talk to me about the influence Horst had on you.

Cathleen Naundorf: When I discovered Horst’s photography, I called him in New York. I realised, that if this is and can be called fashion photography, then I must try and learn it. His work was magnificent. Later we found out, that my family and his family knew each other, because they each had big shops in the town of Weissenfels, in East Germany, on the same street! Can you believe that? He saw my travel pictures and he said ‘ Why don’t you try fashion?’ He influenced me at the beginning, and, of course, later on in my career, I developed my own personal style.

Maryam Eisler: Where do you find your inspiration?

Cathleen Naundorf: Everywhere. I always have pictures in my head! My fantasies drive me. And, I like to realise my dreams. It is these dreams and fantasies that empower me and make me feel alive!

View Cathleen Naundorf’s portfolio: cathleennaundorf.com

Instagram: @cathleennaundorf

Recent Comments