‘Vesuvius in Eruption’ (1817–20) by JMW Turner

The Watercolour World is an ambitious online project to digitise the world’s watercolours and rescue this all-too-often overlooked but artistically and historically significant medium from being forgotten. It is creating a wealth of riches for all of us, says Michael Brooks

Fred Hohler describes the idea as “blindingly obvious” in hindsight. Having spearheaded the creation of a digital record of the United Kingdom’s oil paintings, the former diplomat soon realised his Public Catalogue Foundation had left an ‘orphan’ collection of watercolours in dark drawers, cabinets and basements across the world.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

Now, though, these paintings are emerging, blinking, into the light. The Watercolour World is a rapidly growing website that hosts digital reproductions of watercolours from around the world. Even in these early days – the site’s official launch was in January 2019 – it has become an engrossing collection. Whether you are captivated by an 1840 view of Kings Cross as a rubbish dump – the ‘Great Dustheap’ – or sailors chasing a slave ship near Zanzibar in 1876, a seemingly inexhaustible supply of riches is coming into view. “I have a new favourite about four times a day,” Hohler admits.

Watercolour is often passed over as an unimportant medium, despite the fact that Ruskin, Gainsborough, Turner and Constable all used it at various times. “The lower status of watercolour was owing to the fact that it had been invented relatively recently, had not been used by the Old Masters, and was widely used by amateurs for documentary purposes,” says Sir Charles Saumarez Smith, senior director of Blain Southern gallery, and former chief executive of the Royal Academy of Arts.

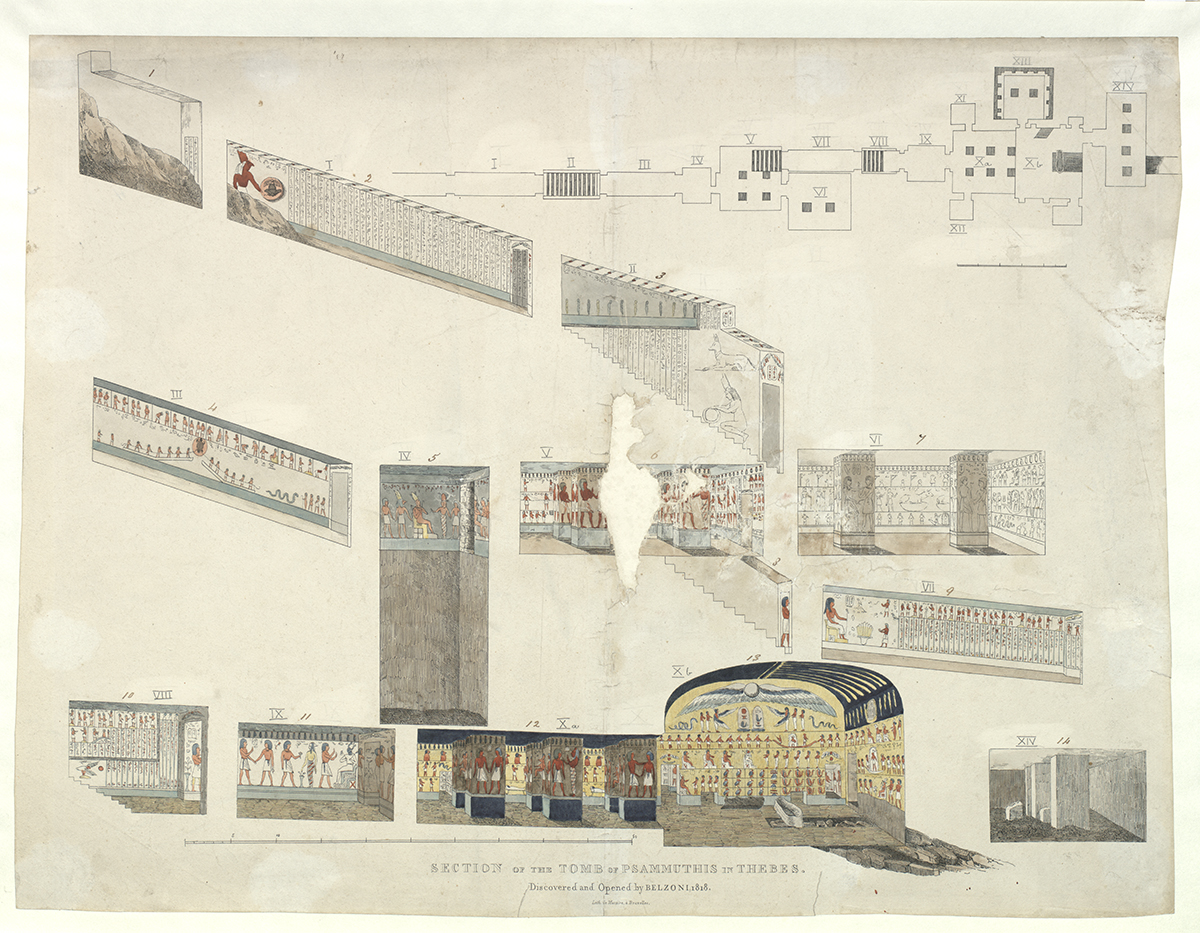

‘Untitled’ [Section of the tomb of Psammuthis in Thebes, discovered and opened by Belzoni in 1818] (1817–20) by Giovanni Belzoni or Alessandro Ricci

At Woolwich Military Academy and elsewhere, officers studied drawing and were taught how to survey a landscape and draw coasts and harbours so that the knowledge of newly gained territories could be spread amongst the military. The watercolourist Paul Sandby was among those who did the training, and the courses were clearly popular, with many accomplished amateur painters emerging from the military academies. As a result, military, government and private collections are awash with watercolour landscapes from across the world, all painted with an attention to detail.

‘The Great Dust- Heap, next to Battle Bridge and the Smallpox Hospital’ (1837) by E. H. Dixon

Many of them, however, have not seen the light of day for decades, if not centuries. “Watercolour as a medium is naturally more susceptible to the effects of heat and light,” says the charity’s chief executive Andra Fitzherbert. “As a result, they tend to be hidden away in dark places or kept in albums where they’re rarely pulled out and enjoyed.”

Read more: 6 mountain restaurants to stir your soul this summer

And that’s where The Watercolour World project comes in. Launched with the patronage of the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall, and realised through support from the Marandi Foundation, The Watercolour World aims to collate hundreds of thousands of watercolour paintings, many of which have never been available to the public until now.

‘Untitled’ [eruption of Mount Vesuvius, 1760–61] (1776) by Pietro Fabris

‘Woodland Scene with a Peasant, a Horse, and a Cart’ (c. 1760) by Thomas Gainsborough

Just as exciting is the scientific potential of the project. Many watercolours offer a view of a world that no longer exists and are a means by which conservationists, ocean scientists, coastal engineers and geologists can reach back into the past, make sense of the present, and perhaps safeguard the future.

There is strong precedent for this. In the 1860s, the government moved the Gunditjmara, the Aboriginal people of the area, off Tower Hill, an extinct volcano in Victoria, Australia. They proceeded to clear the land’s thick vegetation for grazing. Only in the 1960s was there a move to restore the area. Fortunately, the watercolourist Eugene von Guérard had made a painting of the virgin land in 1855, a painting so detailed that the authorities could identify more than 20 species of plant to use in the restoration project.

Read more: Geoffrey Kent discusses the influence of top-earning millennials

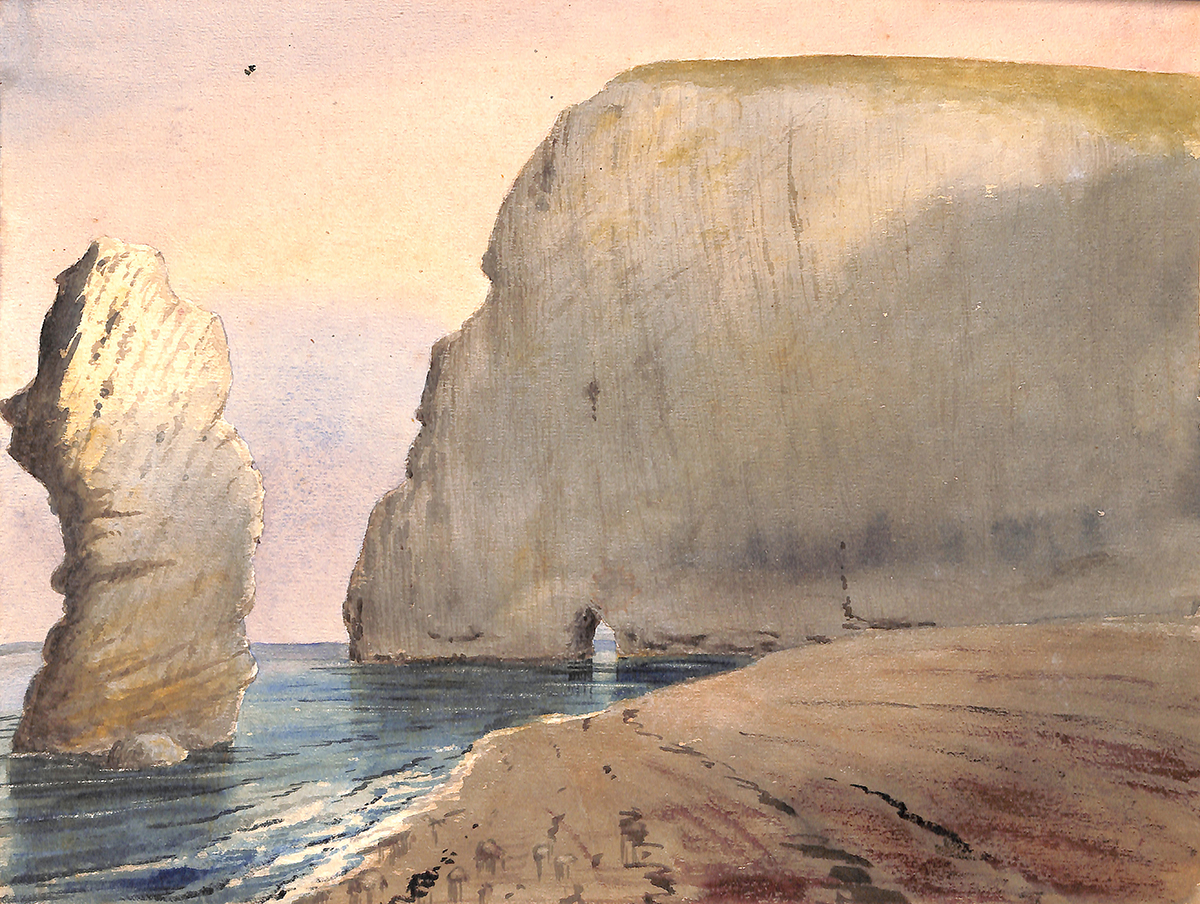

The vast and growing catalogue of paintings in The Watercolour World means that similar restorations might be possible in other areas. Some of the paintings are already in use in a project to catalogue changes in the British coastline over the past 250 years. Geologist and coastal engineer Robin McInnes is in the closing stages of The State of the British Coast Study, which was commissioned by The Crown Estate, the European Commission and Historic England. Using a range of sources, including paintings in The Watercolour World, McInnes has been able to discern where and when beaches have eroded, cliff lines have changed and engineering projects have made an impact on the shoreline. The results of the study will be used to aid conservation and ecological efforts. “They’ve been feeding me coastal images, many from private collections that have never been seen before. I’ve been able to use some in my study,” McInnes says. Some are from less highbrow sources, too. “Postcard companies employed some prolific watercolour artists to paint the coast.”

‘The Encampment in Hyde Park’ (1781) by Paul Sandby

Another environmental application will be in surveys of glaciers. Watercolours have a strong history here. The first known depiction of a glacier, made in 1601, was Abraham Jäger’s painting of the Rofener Glacier in Austria. By the middle of the 19th century, artists were painting faithful renditions of scenes at the heads of glaciers. John Brett’s Glacier of Rosenlaui, for instance, shows the position of the glacier in 1856, as well as a detailed portrait of the erratics, the boulders at its head that had been carried by the ice. The Watercolour World’s collection includes renditions of glaciers by Horace Bénédict de Saussure, the precision of which give a marker for recent glacier retreat. “Climate change is on almost everybody’s mind right now, but in the 19th century artists and scientists were working together documenting glaciers,” says Barbara Matilsky, who curated last year’s ‘Vanishing Ice’ exhibition at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis. Many of the show’s 47 artworks, dating from 1860 to 2017, showed evidence of climate change.

‘Bat’s Hole’ (no date) by Henry Joseph Moule

Using The Watercolour World as a scientific resource is a “fabulous idea”, Matilsky says. She points out that artists and scientists have long worked together to document the natural environment. In the 19th century, for instance, geologists at the Museum of Natural History in Paris commissioned artists to paint glaciers. “They wanted to show students what they look like so they could intuit from these works the processes that formed the glaciers,” Matilsky says. “Scientists were very much aware that artists were important in communicating scientific concepts.”

At the other end of Earth’s temperature scale, The Watercolour World includes dozens of paintings of volcanoes. The 1776 eruption of Vesuvius is particularly well represented, because the British diplomat Sir William Hamilton commissioned the artist Pietro Fabris to paint 54 illustrations of the volcano for his scientific studies of its geology.

Read more: Sir Rocco Forte on building his empire of luxury hotels

Fitzherbert is keen to point out that The Watercolour World will be of relevance to everyone, not just to scientists and culture professionals. All of the images have searchable location and keyword information, allowing people to explore their family history and their local area’s past. “We want to make it personal so that people can navigate through a map and find local places of interest and find family homes or where they were brought up,” she says. “People can use these paintings to reflect on their own lives.”

The Watercolour World operates a small team, equipped with a Fujitsu ScanSnap scanner, to perform the digitisation. In addition, a group of volunteers tag and categorise the images, adding their locations and all relevant data about the artist’s intentions. Only then are they uploaded onto the site.

The project has yielded unexpected gains. One is that, in some ways, the website offers something even better than a gallery viewing. The scanners provide a depth of colour and an ability to zoom in that just aren’t available in a static display. What’s more, observing the paintings on screens means they are, effectively, backlit. “You see it in an entirely different way,” Hohler says. “It’s given a brilliance to these images that you don’t otherwise get.”

Though the collection is already clocking in at 83,000 images, a queue is forming. “The wonderful thing is, as soon as you launch a project like this, it belongs to everybody,” Hohler says. Many institutions and organisations have offered their digitised collections. The Watercolour World is even receiving offers to scan private collections that have never been made public, let alone digitised. “We’ve been overwhelmed by people’s positivity and encouragement,” Fitzherbert says.

Find out more: watercolourworld.org

This article was originally published in the Summer 19 Issue

Recent Comments