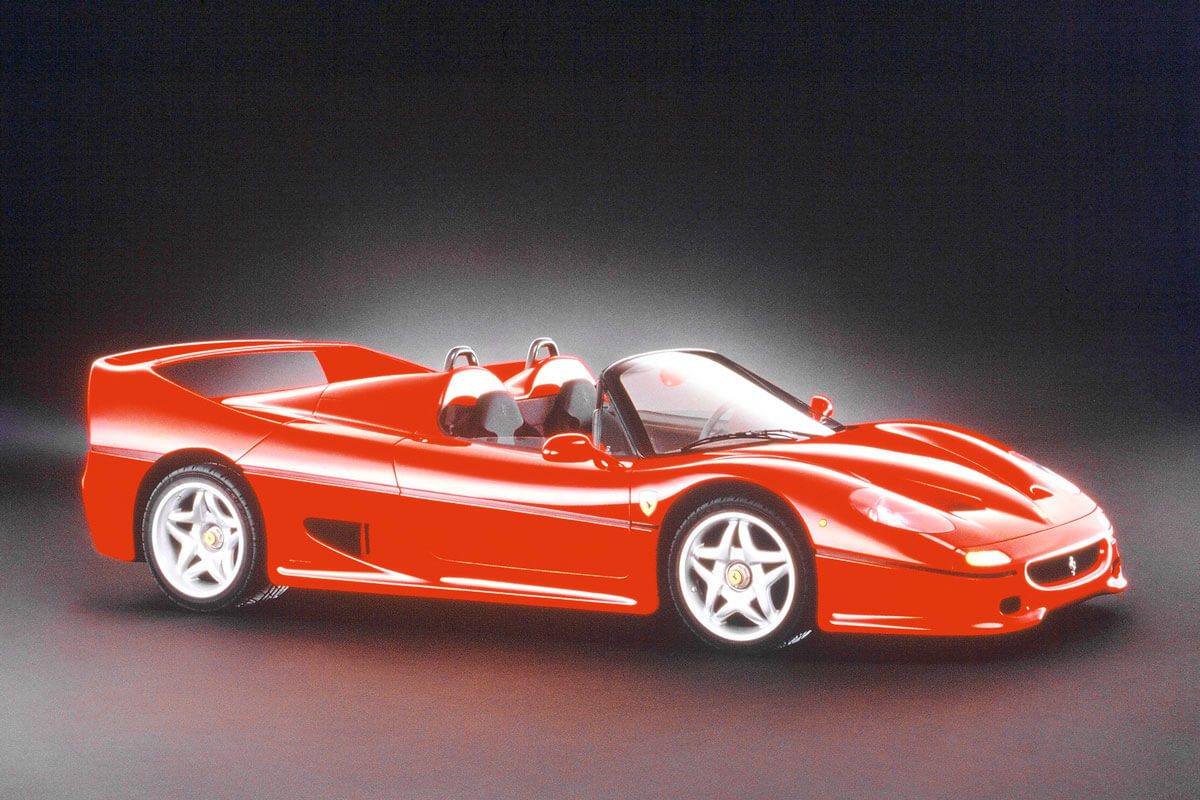

The 1997 Ferrari F50, of which only 349 were made. Image courtesy of Ferrari S.p.A.

Classic cars are, for a new generation of luxury collectors, something of a conundrum. On the one hand, they are perhaps the ultimate ‘investment of passion’, objects which you can cherish and use, and which nonetheless gain value over time. On the other hand, for some people the idea of a classic car conjures up an unappetising image of an ancient, uncomfortable contraption sitting broken down by the roadside, leaking unidentified fluid, while people of today breeze past in Teslas or in the back of their Uber.

And I sympathise with both sides. With all the opportunities afforded by digitization, internationalisation, and a connected world – developments I see as almost entirely positive – who now has time to spend their Sunday mornings trying to fiddle around with a vehicle that, even when running properly, has no air conditioning, no connectivity, and is slower and noisier than the average contemporary people carrier?

And yet…the greatest cars are a combination of art, engineering, and, for those who enjoy driving, enjoyment beyond what many of the hi-tech vehicles of today can offer. Today’s new car market offers dozens of cars that can exceed 150 mph, and post breathtaking times on racetracks, but most do this so competently that the joy of driving has turned into something akin to a dull feeling of being driven. And this will only accentuate as people increasingly are driven, by self-driving machines.

Read next: Danish model, Rianne ten Haken on the fashion industry and teaching yoga

All of this has been postulated as a reason behind the rise of what has been dubbed the ‘modern classic’ collector’s car market, a term that your author helped bring into the mainstream back when this development was in its nascence a few years ago. The term encompasses cars that are as rapid, comfortable and reliable as most contemporary cars, but, through either quirks of engineering or having been manufactured at the point where the old classic car era turned into the new, are as enjoyable as the older ones.

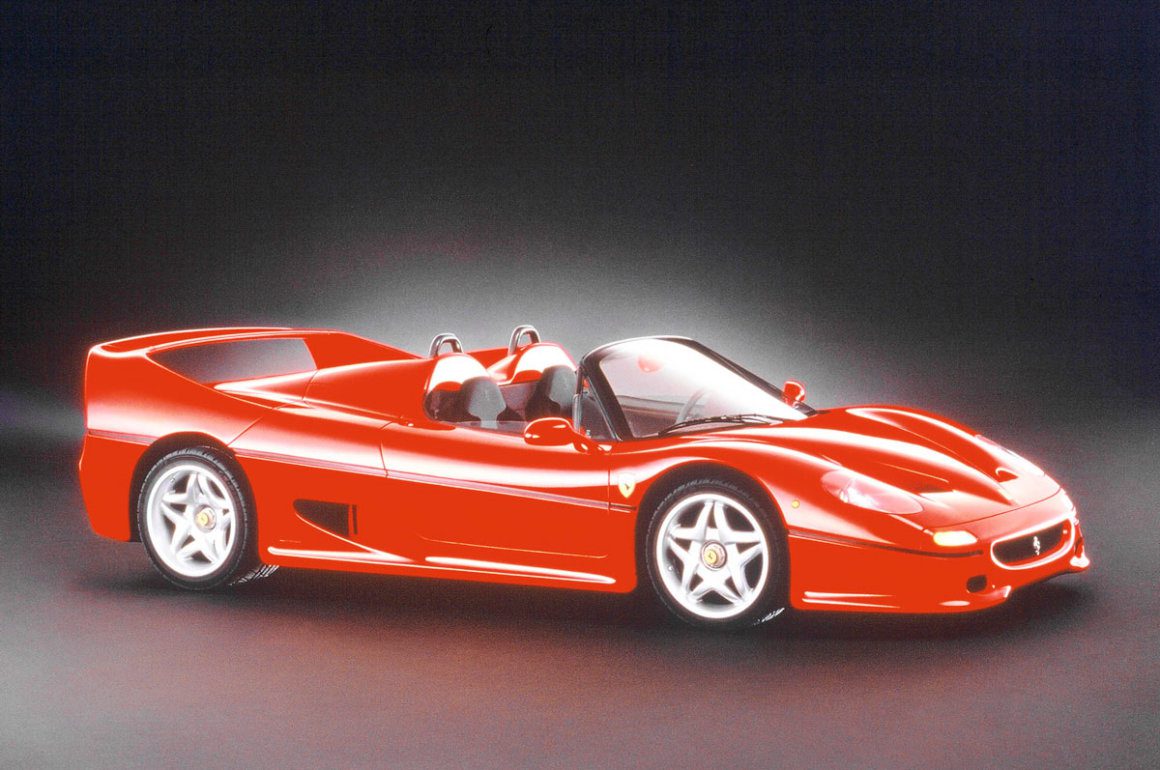

The 1995 Ferrari F512M, of which only 501 were made. Image courtesy of Ferrari S.p.A.

A word of warning though. The ‘modern classic’ has been adopted by marketeers and average car dealers, to the extent that it is now turning meaningless and being used as a cover for almost any used car of the past two decades. Most of the ‘modern classics’ so dubbed at today’s auctions are nothing of the kind. To have collectability, the criteria for a modern classic are the same as for anything collectable: they have to have been made in limited numbers, be special in some way (via brand, or history), and be genuinely desirable. A Ferrari F50 (349 made) or F512M (501 made) from the 1990s is a modern classic; a Ferrari 360 (more than 15,000 made) is likely not. (Full disclosure: there is a F512M in my stable). Production numbers are partly, but not wholly, responsible for this distinction.

Does all of this signal the end of the era of the traditional ‘classic car’, with its quirky, hand-beaten body panels, tiny production quantities, and 1950s and 60s design quirks? The obvious answer is of course not: assuming you could find them, you could buy seven or eight of my 1995 Ferrari F512Ms for the price of a single 1969 Ferrari Daytona Spider, or 365 GTS/4 to give it its correct nomenclature. (I use Ferraris as a reference partly because they are the most significant brand in car collecting, and partly because I am most familiar with them.) The most expensive cars ever sold are still those (mainly Ferraris) from the 1950s and 1960s.

But real modern classics are gaining in value fast. Certain Porsches of the 1990s have overtaken the prices of all but the rarest of their siblings from the 1960s, and some 1990s cars, like the McLaren F1, are now selling for more than ten million (pounds, euros, or dollars). Even relatively common but collectible Ferraris, like the 1997 550 Maranello (around 3000 made), have trebled in price over the past four years.

McLaren F1 GTR

Whether they will continue to make ground is a question in the mind of collectors – although it tends to get blown out of my mind when I am driving at full speed in any of my Ferraris, as they are of the era when total concentration is required of a driver at any speed, which is a key part of their appeal. One the one hand, there is plenty of evidence that Millennials and Generation Y are less interested in cars: as LUX Contributing Editor and columnist Jean-Claude Biver, CEO of LVMH Watch & Jewellery told me, “teenagers do not wear watches and they do not buy cars”. (Biver is himself a significant collector of what he would call ‘real classics from the pre-electronic era’, including a gorgeous 1966 Ferrari 275 GTB/4, worth multimillions). There is also an argument to say that the younger generation of purchaser is only interested in the newest, most connected cars. I broadly call these the obsolescence argument and the antiques argument: either collectible cars will become like fax machines, entirely redundant; or they will become like antique furniture, out of fashion.

Read next: A futuristic world of modern bodies at Past Skin, MoMa PS1, New York

There is also the view that the current spike in prices for all these cars is due to money chasing after investments in an era of low interest rates, which will inevitably change.

I don’t know. These are probably correct for the vast majority of self-proclaimed ‘modern classics’ which are neither as cool as the real classics which preceded them, or as good as the cars of today. But when I am out in my cars, there is no shortage of young people taking selfies or videoing the car, and many of my spectators are, in time-honoured tradition, small boys dreaming of fast cars who one day will grow up to be purchasers of the car they admired in their youth. Uber, Tesla, and regulations restricting the use of cars in cities can only do so much. And while fax machines and 19th century desk bureaux may be worthless today, try telling your art dealer that a Da Vinci or a Monet is now worthless because of the demand for Jeff Koons.

Which is why I am continuing to acquire modern classic cars – the right ones. And why you will be reading, in LUX, some detailed articles on this most exciting of ‘investments of passion’.

Recent Comments