Originally called the Prinzessinnenpalais, Deutsche Bank’s PalaisPopulaire opened in September this year

Featuring over 300 works by some of the art world’s biggest names alongside emerging artists, Deutsche Bank’s new exhibition space, the PalaisPopulaire, presents a museum-quality show of inter-generational exploring the numerous ways in which artists work on paper – and with surprising results. Anna Wallace-Thompson hopped over to Berlin to check out its inaugural show, The World on Paper

What would be the art world equivalent of a kid walking into a candy shop? Probably something akin to walking through swish, space-age sliding doors into a room to find oneself surrounded by names such as Joseph Beuys, Marcel Dzama, William Kentridge, Imran Qureshi, Katharina Grosse, James Rosenquist, Dieter Roth, Andy Warhol, Bruce Nauman, Gerhard Richter… the list goes on. And on. And on. To say that the inaugural exhibition of Deutsche Bank’s new arts, culture and sports space at the fittingly titled PalaisPopulaire is something of a showstopper is to put it mildly.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

Opening in late September after extensive renovations, the 18th century venue – originally called the Prinzessinnenpalais – has been remade twice during its colourful history, once in the 1960s, when it became a sort of ‘it’ destination, and now by architectural firm Kuehn Malvezzi. In its newest shiny incarnation it offers over 750 square metres of exhibition space, and The World on Paper brings together 300 works (you guessed it, on paper) by 133 artists from 34 countries. “The focus of this show was really to present the heart of our collection,” says Friedhelm Hütte, curator of the show and head of Deutsche Bank’s worldwide art programme. “Paper is so interesting because artists write on it, they use it as a kind of diary, they can cut it, make three dimensional works, and so we thought – this is almost like the laboratory of an artist, you can see what they are thinking, watch that process of how they develop their ideas. Paper is a very authentic medium and often so innovative – first ideas are often fixed on paper.”

Study for “The Swimmer in the Economist,”, 1996/97James Rosenquist

The exhibition is divided into three sections, with visitors invited to explore these different ‘worlds’ across three floors, wandering through investigations of the body and self-image, abstraction on paper, and examinations of urban spaces and technology. It could be a messy combination of disparate subject matters, yet somehow it’s not. “It was also important for us to present more than just the big names, the ‘hit list’, as it were,” says Hütte. “We wanted to have some surprises and show artists either who aren’t that widely known, or little-known works by well-known artists, such as the early works by Gerhard Richter we’ve selected.”

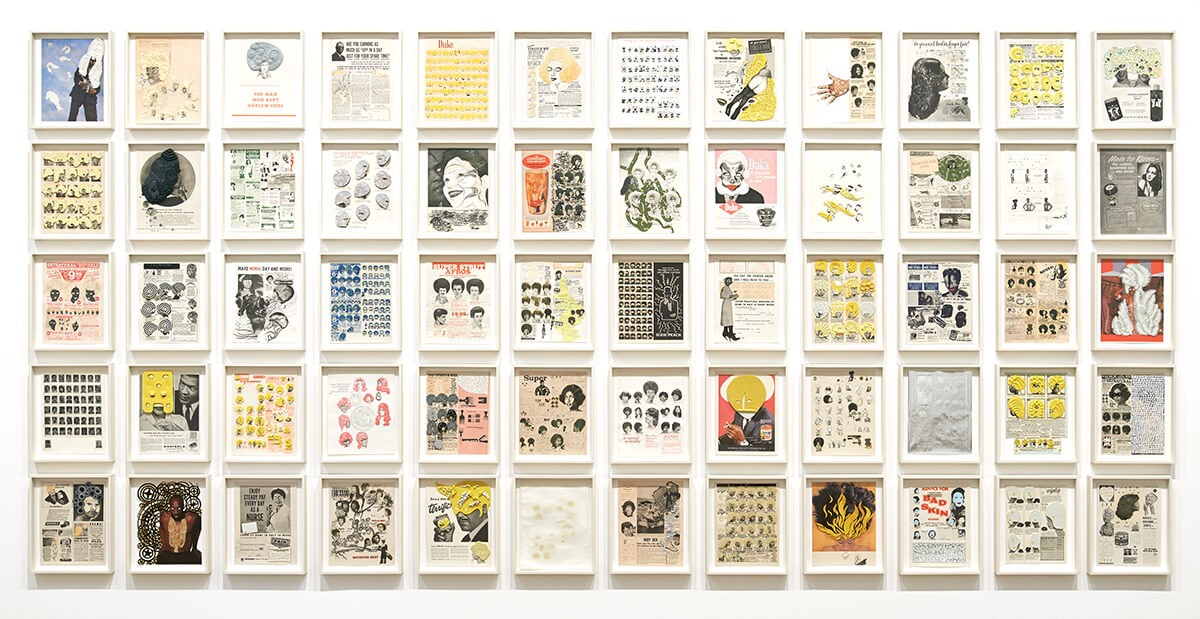

“DeLuxe”, 2004/05 Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo credit: Alex Delfanne

In fact, it would be easy for an exhibition like this to pay lip service to big names and act simply as a promotional tool for that ‘hit list’, and the grandeur of Deutsche Bank’s (admittedly impressive) corporate collection. In fact, what is so interesting about The World on Paper is precisely that it is not a ‘safe’ show – after all, corporate collections can so easily become bland lists of big names, ticked off with due diligence but with little willingness to push the envelope into uncomfortable territory. Not so here. See, for example, Iranian artist Parastou Forouhar’s untitled pieces from her series Take off Your Shoes (2001/2002), which depict women in chadors dealing with the bureaucracy of the Islamic regime. Then there is the riot of delight that is American artist Ellen Gallagher’s multi-piece grid of photogravures, DeLuxe (2004/05). Take an array of magazines and promotional materials from the 1930s to 1970s, then remake them with interventions in screen print, embossing, laser cutting, tattoo engraving (yes, really) and Plasticine and what do you get? A bitingly witty investigation of cultural identity and race through the countless advertisements for beauty creams, hair pomades, wigs and more, that have been targeted at African Americans. “Of course we could have put together a show without any risks,” says Hütte. “We could simply have focused on the big names and the big works, but this is what one would expect, and what would be interesting about that?”

Read more: The Secret Diary of an Oxford Undergraduate – Freshers’ Week

One of the most delightful surprises is the sense of delicacy that winds its way through the works. There are the bold heavy-hitters, of course – the Rosenquists, the Kentridges – but there is immense tenderness too, such as in the evocative Heartbeat Drawing 24 Hour (1998) by Japanese artist Sasaki, or Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s witty take on traditional Chinese manuscripts in My History (2008), in which traditional Chinese painting meets life in the UK (complete with punting in Cambridge). “There are very special pieces here that one wouldn’t expect,” agrees Svenja Gräfin von Reichenbach, director of the PalaisPopulaire. “I find the three drawings by Bruce Naumann we have on display particularly special, as well as the paper works by Richter – they are so private.”

“Moondiver II” by Zilla Leutenegger at Deutsche Bank’s PalaisPopulaire

Ultimately, The World on Paper is a great barometer of our times – it stretches from Post-war Modernism all the way to the present day, and marks the increasingly international nature of Deutsche Bank’s collection. “We wanted this so be our first really international show,” says Hütte. “The character of the collection has completely changed during the last decade, and of our 50,000 works, here we have 134 artists from 34 nations represented.”

Perhaps the best indicator of what the show represents – and what it promises for the future of the PalaisPopulaire – is the playful intervention in the main space’s rotunda. Here, Zilla Leutenegger has installed a multimedia mural and video projection entitled Moondiver II. As visitors wander through the impressive space with its winding staircase, a large, starkly-drawn black construction crane carries a delicate, luminous moon back and forth. It’s that combination of bold and delicate, traditional mural and contemporary video projection that sums up The World on Paper: everything is possible, and this is just the beginning.

“The World on Paper” runs until 7 January 2019 at PalaisPopulaire

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

Recent Comments