Nubeluz at the Ritz-Carlton New York, Nomad by Martin Brudnizki bring guests to the skies of New York

Martin Brudnizki and Bruno Moinard are two of the most celebrated names in interior architecture and design today. Here, Brudnizki takes LUX on a grand tour of Martin Brudnizki Design Studio’s most recent projects, while Moinard shares his design inspiration and creative process

Martin Brudnizki

Nubeluz at the Ritz-Carlton new York, Nomad

With Nubeluz located on the 50th floor of the Ritz-Carlton, our concept for its interior was to create a star in the New York sky. The project’s core is a central backlit onyx bar, and the surfaces are designed to reflect its lighting. A high-gloss lacquer ceiling, a marble floor, mirrored and onyx tables, plus six statement brass saucer chandeliers ensure that light bounces around the room in a magical way.

Martin Brudnizki

The colour scheme takes the project from lightbox to jewel box with a teal envelope to the walls, floor and ceiling, highlighting the coral seating in its luxurious mohair and flame stitch-patterned fabrics. We didn’t want to disrupt the views, so sheer teal-trimmed roman blinds hang across the windows. Our interior is a celebration of light and the city, referencing the classic hotel bar and saluting the views over an iconic skyline. It is modern and quintessentially New York.

Hôtel Barrière Fouquet’s New York

This is the illustrious French five-star hotel brand’s first foray into the US. In Paris it is located on the Champs-Élysées, so you might think its natural New York home would be the Upper East Side, but its team chose Tribeca – a decision I love. Our design challenge was to combine a distinctly Parisian ambience with a downtown location.

Hôtel Barrièrre Fouquet’s New York by Martin Brudnizki brings the iconic Parisian hotel to Paris

We have brought together high glamour and elegance in a modern, timeless design, while leaning on the building’s loft-style architecture that blends seamlessly into the Tribeca landscape. Parisian design accents can be found in the rich materiality and colour palettes, while a carefully curated art collection, featuring many local artists, has a gritty urban appeal.

hotelsbarriere.com/en/collection-fouquets/new-york

Vesper Bar at The Dorchester, London

With this project, it was important to respect the past while bringing it to a new era. We were inspired by celebrated Roaring Twenties creatives, such as Cecil Beaton and Oliver Messel, who each had a history with The Dorchester.

Vesper Bar at the Dorchester by Martin Brudnizki

Their inspiration was integral to the spirit of this landmark bar. We also nodded to designer Syrie Maugham in our use of the mirrored columns. The hope is that the Vesper Bar inspires another Roaring Twenties.

Mother Wolf, LA

Situated off Sunset Boulevard, Mother Wolf is a playful Italian restaurant that has become a magnet for LA celebrities since its opening in 2022. Working with chef Evan Funke and Ten Five Hospitality, we created a homage to the glamour and elegance of Italian design.

Mother Wolf, LA by Martin Brudnizki

References to architects Gio Ponti and Carlo Scarpa can be found in the dining chairs and central bar, while a trompe-l’oeil scene depicts lemons and pomegranates – an ode to Italy’s chic riviera. With its Murano-glass lighting, antique mirrors and Siena-marble table tops, every aspect of the restaurant’s interiors connects to the design heritage of Italy.

Bruno Moinard

I am guided by lines, materials, light, energy and movement: whether in my work as an architect – in our projects around the world with Claire Bétaille for famous brands and high-profile clients – or in my more intimate work as a designer and painter.

Bruno Moinard in his studio amongst his paintings

When I began to appreciate beautiful old cars – and I have three mythical English models – I saw their design is a distillation of everything that makes me vibrate in my creative process. I see these qualities in the bodywork, the leather, wood and chrome, the colours, the interplay between interior and exterior, the vision of the future in front of me and of the road travelled behind.

Interiors of Hôtel Plaza Athénee lobby, Paris by Bruno Moinard

So the challenge I set myself is to work with authenticity to evoke an emotion, to give a simple pleasure and generate unique sensations. This is luxury. It has nothing to do with glitz or so-called rarity.

Hôtel du Marc lobby, Reims by Bruno Moinard

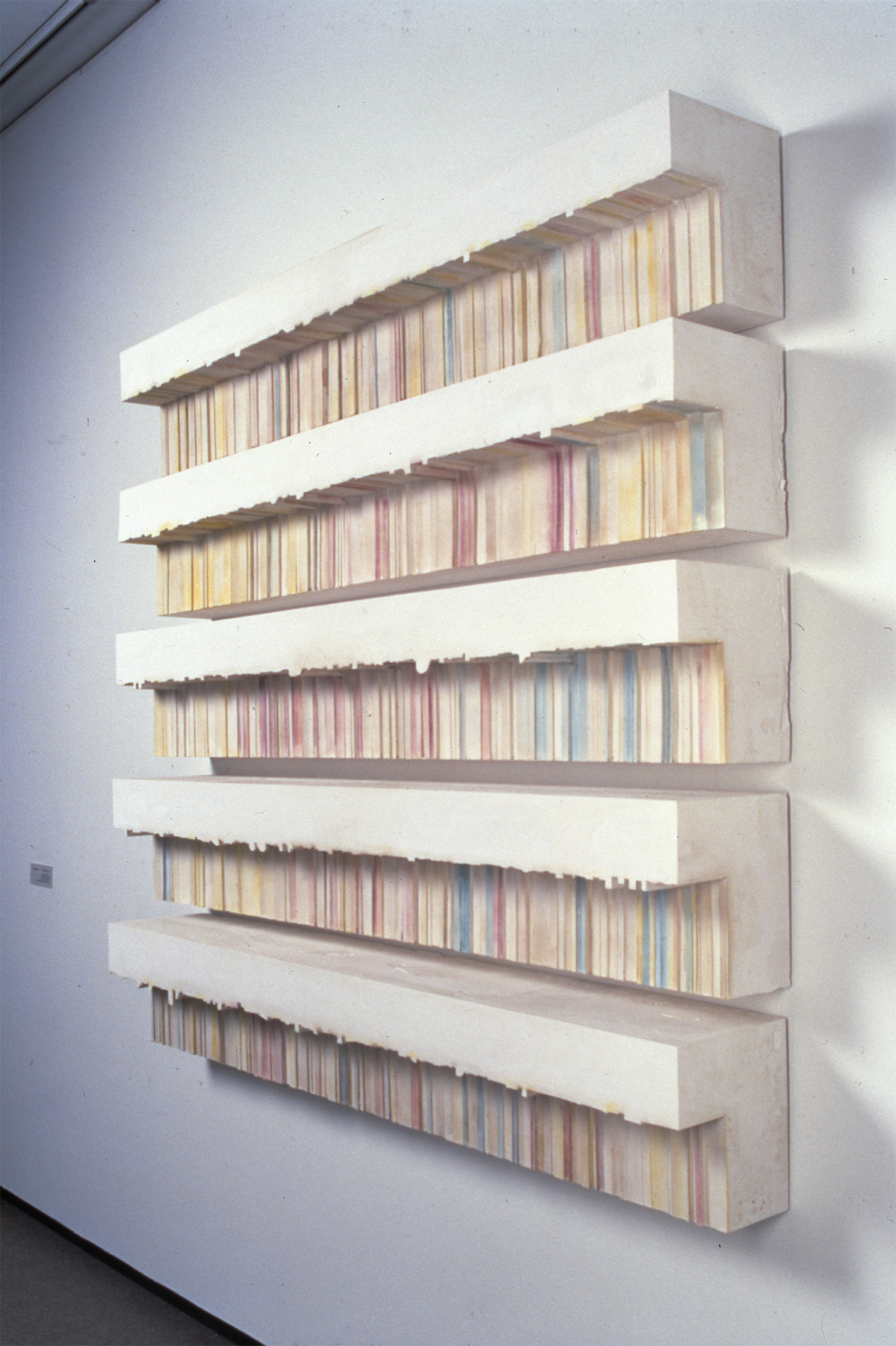

So in the cellars of Clos de Tart, a 1,000-year-old Burgundy vineyard with a Cistercian history, we built on the exceptional quality of the historic building, bringing light into the space, giving it life, to place it in harmony with the pure elegance of the wines.

Hôtel du Marc dining room by Bruno Moinard

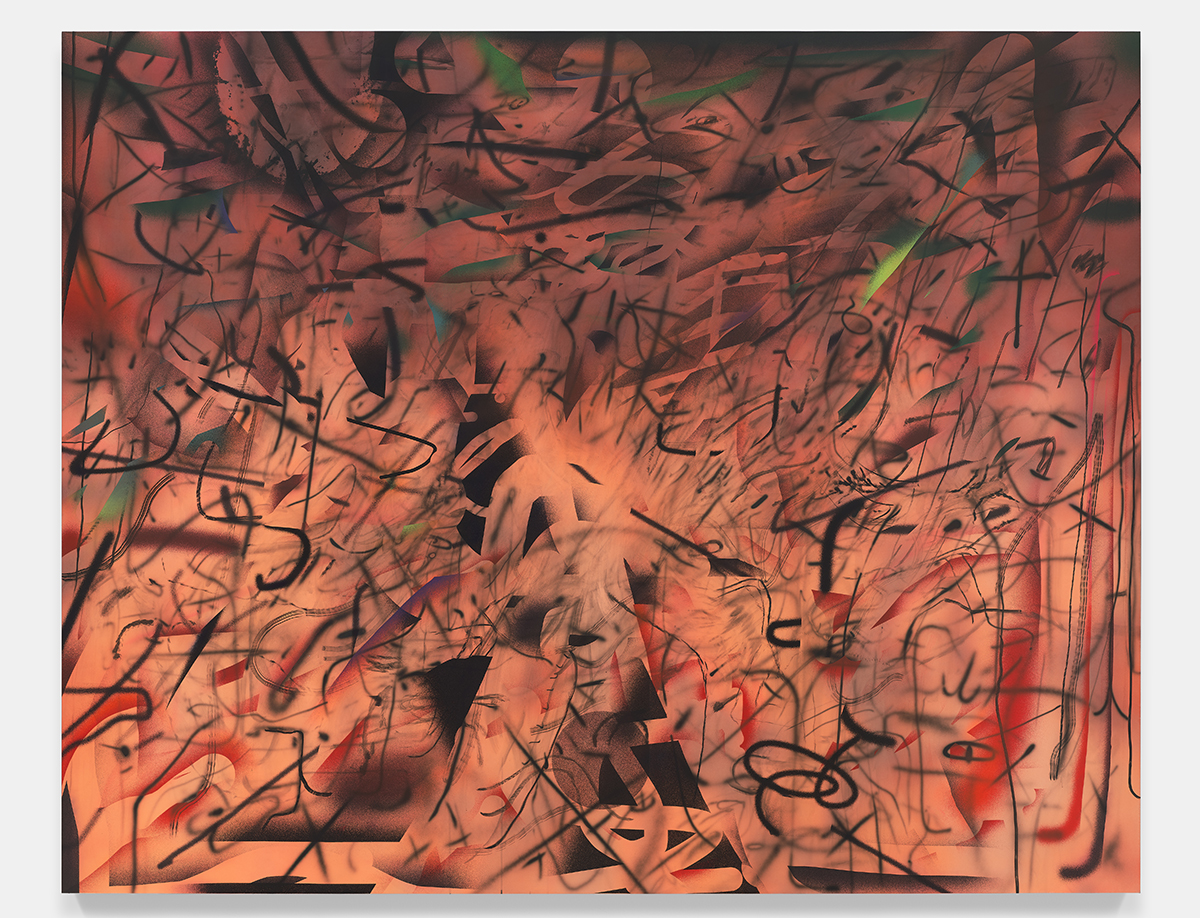

In “Résonance”, my recent exhibition in Paris, we made each painting an experiential space that I invited people to enter. My recent furniture collections also seek this sense, which has a direct impact on quality of life and on the welcoming nature of a space.

One Monte-Carlo living room, Monaco by Bruno Moinard

My lights, furniture, carpets and objects bring freshness and softness with natural forms and materials. I am privileged to work in complementary fields and my inspiration in both is based on the same triptych of emotion, continuity and sustainability, while promoting the finest workmanship and expertise.

This article first appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2023/24 issue of LUX

Recent Comments