Triumph of Death (1562), Pietr Bruegl the Elder

In the second edition of her monthly column for LUX, artnet’s Vice President of Strategic Partnerships Sophie Neuendorf looks back on the emergence of the Renaissance following the Black Plague, and towards a more positive and creative future

We can all agree that this year has been one of the toughest we’ve experienced during our life time. It certainly was for me. The consequences of an unprecedented global pandemic have been, and still are horrifying and in many ways, unbelievable. But, the question is: how will generations to come analyse and learn from this particular moment in time?

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Let’s look back at another pandemic, which was arguably much worse: the Black Plague, which struck Asia and Europe during the mid-1300s. It arrived in Europe during October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. Most sailors aboard those ships were dead, and those still alive were dangerously ill.

Over the next five years, the Black Death – a terrifyingly efficient disease – would kill more than 20 million people in Europe, about a third of the population. At the time, no-one knew exactly how the disease was transmitted, or how to prevent and treat it. A grim sequence of events unfolded for which, in the middle of the 14th century, there was no rational explanation.

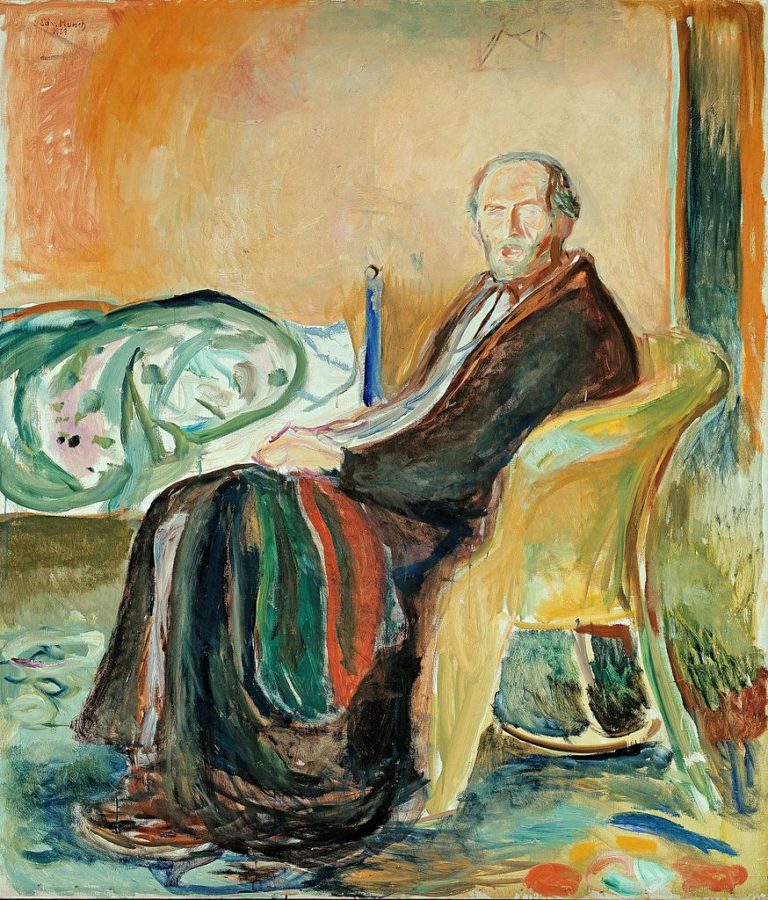

Self Portrait after Spanish Influenza (1919), Edvard Munch

Today, however, we know that the Black Death attacks the lymphatic system, causing swelling in the lymph nodes. Left untreated, it can spread to the blood or lungs and is highly contagious.

Following the Black Plague, a preventative method was developed in Italy, which we saw repeated this year: quarantine. In order to slow the spread of the disease, returning sailors were mandated to stay on their ships for 40 days ‘quarantine’, relying on isolation to slow the spread of the disease.

Read more: Life coach Simon Hodges’ tips on breaking free from destructive behaviour

Following the end of the Black Plague, a new era unfolded in Europe, known as the Renaissance (or rebirth). The impact of the Black Death had been profound, resulting in wide-ranging social, economic, cultural, and religious changes. These changes, directly and indirectly, led to the emergence of the Renaissance, which was one of the greatest epochs for art, architecture, and literature in human history.

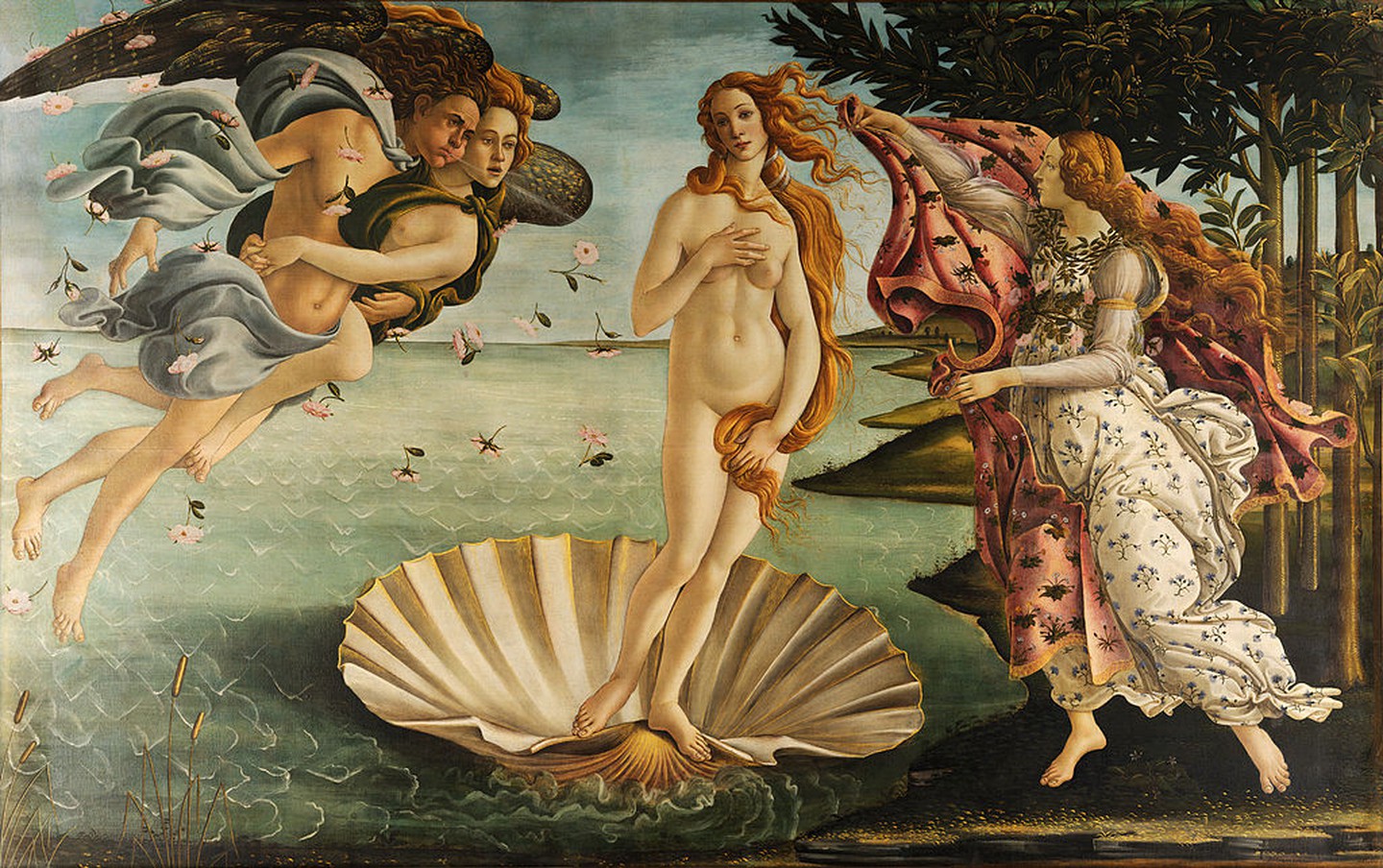

The Birth of Venus (1484), Sandro Botticelli

After a period of pessimism, introspection and recovery, a time of enlightenment and renewal began. The arts especially flourished, as artists documented this time of change and upheaval. Through their creativity, artists wrestled with questions such as the fragility of life, religion, spiritualism, and the pleasures of living. Artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and Albrecht Dürer dominated what’s known now as the humanistic high Renaissance period. The prevailing theme was the seizing of life, driven by positive change, knowledge and nature.

Read more: Richard Mille’s collaboration with Benjamin Millepied & Thomas Roussel

How will we respond to the pandemic we’re facing now? Will the development of a vaccine result in a period of introspection, creativity, and change? Will we – having faced an invisible, deadly enemy – emerge more tolerant, grateful, and accepting of change?

La Primavera (1477), Sandro Botticelli

A near-death experience usually results in a renewed zest for life, happiness and gratitude. Within the art world, many of the archaic norms have already been replaced during the course of the year. As artistic expression and culture define us, not only as individual nations, but in terms of humanity, we should ensure that this moment in history is not a missed opportunity.

Covid-19 has forced us to profoundly rethink the way we live, the values we have, and world we’ll leave for our children. Covid-19 has also forced us to trust in digitalisation and to rethink the way we experience and trade art. For context, while the art market declined by 58% in the first half of this year, online art sales increased by nearly 500% during the same period. There has been a flurry of creativity and inspiration, from artists doubling down in their studios to document the zeitgeist, to museum and galleries embracing VR and making their inventory accessible online. Let us embrace these changes and welcome an opportunity for a more transparent, accessible, and tolerant art world.

Browse artnet’s current auctions via artnet.com/auctions

Recent Comments