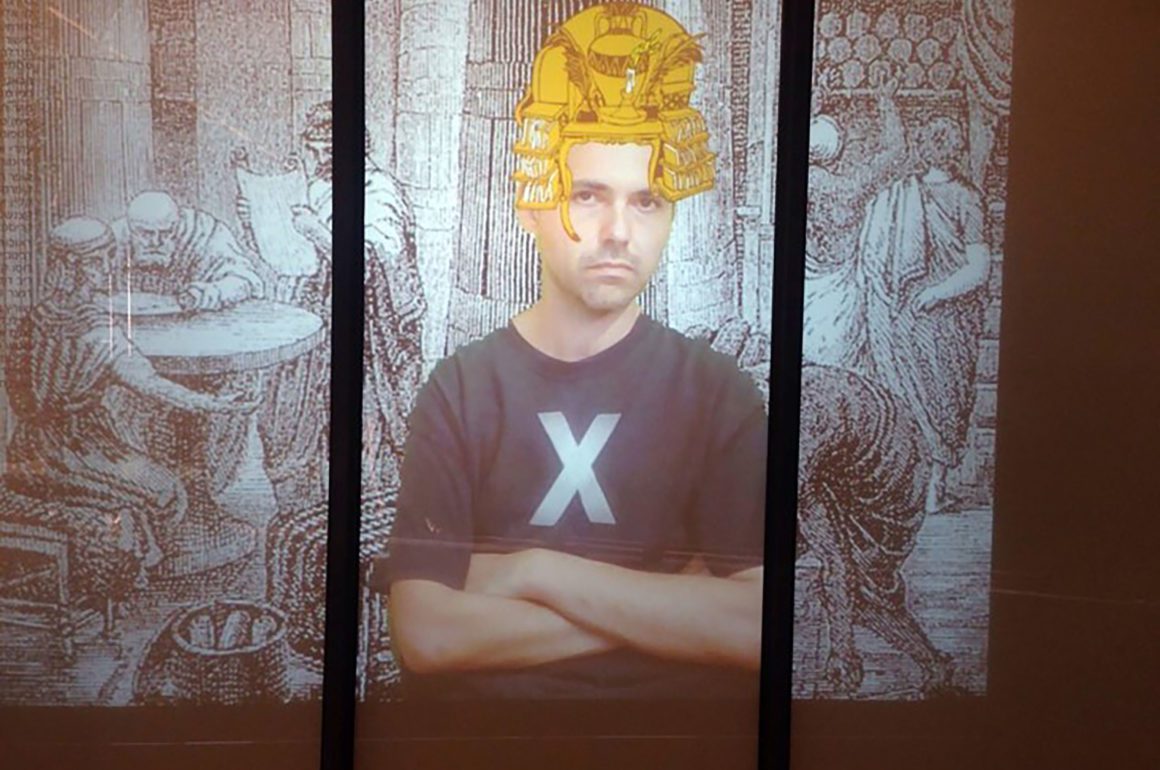

Poet, co-founder of poetry night BoxedIn and host of Jawdance, Yomi Sode

Eclectic, competitive and radical, Slam Poetry is a fringe form of spoken word poetry and protest, blurring the lines between hip hop and the performance arts. It is an increasingly popular art form for those wishing to express political protest and radical emotion, due to its dramatic intensity in action as well as in language. It is also unique for its organic propensity to resist commercialisation and remain authentic on stage.

Poetry slams provide a platform for every kind of person to express their feelings on issues as far-reaching and globally significant as the refugee crisis, Black Lives Matter, identity politics and oppression of sexuality. As the world moves towards ever-increasing commerciality of art and self-expression – an example being the twisted use of feminism as a fashion statement – it seems that Slam Poets may be the only people with the ability to resist these falsehoods and cut straight through to the truth of our times.

Rhiannon Williams speaks to Yomi Sode, the talented Nigerian-born London-based poet, co-founder of landmark poetry night BoxedIn and host of Jawdance, on what makes Slam Poetry special.

LUX: Did you always want to be a poet?

Yomi Sode: No, poetry kind of crept in. I used to MC before, I used to DJ, I still have my vinyls – I am a proud collector of what I could class as ‘vintage grime’. I kind of ventured in all aspects and areas of music first.

Follow LUX on Instagram: the.official.lux.magazine

LUX: How did you discover Slam Poetry?

Yomi Sode: I first discovered Slam Poetry through a legend of a poet called Joelle Taylor. I saw this event that was happening, I think it was a SLAMbassadors event, and I thought this was cool to get involved in, and that’s how I met Joelle. I’m now faced with what is Slam poetry and I saw how these groups came up, how these individuals came up to do solos and it just blew my mind. But even after the event it wasn’t enough to pull me in to be interested in spoken word poetry. I loved it, but it wasn’t what I was used to with MC-ing, it was a very different form of expression.

But then I was in New York and I wanted to share some poems. The Nuyo [Nuyorican Poets’ Café] is a staple spot in terms of spoken word and the evening I got there I signed up but I didn’t realise it was a Slam – I accidentally signed up for my first Slam. Not only a Slam, but a Slam in America. And I actually got through to the final but the next stage of it was on the Friday and I wasn’t in New York for it!

LUX: How would you describe Slam Poetry to someone who hasn’t encountered it before?

Yomi Sode: It’s so difficult because Slam Poetry in different parts of the world is expressed in many different forms. So, should you look at the way the States take it on it has a very intense feeling to it; it’s very passionate, it’s driven with purpose. Folks don’t just go onto that stage and read a poem, they bare absolutely everything. It’s very personal, it can get very political, they take it very seriously there. In England what I’ve noticed is that it can be lighter, it can be a bit comedic, and of course there are many elements of seriousness, but the core of how it is in the states is very different.

You can make something very special out of 3 minutes’ worth of work and that’s an experience – as a a poet and an audience member – that you remember for a very long time.

Yomi Sode in performance

LUX: What’s the difference between a poetry Slam and a spoken word night?

Yomi Sode: I just came off the back of judging UniSlam in Leicester and there was this one piece that actually made me uncomfortable. And that’s what the power is of a Slam compared to your typical poetry night. At Jawdance for example, each person comes up to an open mic and you’ll see them again next month probably. With a poetry slam, even though the ethos isn’t about the winning and more about the experience, the process, you are still there to win and through that drive comes this energy. You get triple the amount of passion for the message coming through.

Read more Poetry Muse: The augmented poetry of Eran Hadas

LUX: You said you were judging UniSlam. What kinds of things are you looking for in these Slam poets’ performances?

Yomi Sode: It was very hard when I was judging. I was looking for any quirky lines, I was also marking up anything that sounded a bit cliché. One poet I remember went on there and he started with ‘my love’ and I was like oh god, because straightaway when you start with a line like that, I already know where you’re going.

LUX: What do you think is the unique appeal of a poetry that is performed and not just read? How does it feel to stand up on stage, vulnerable and utterly visible, sharing your art with an audience?

Yomi Sode: Performance is very important. To stand on stage and just read a poem and trust that you will feel what I’m feeling. I could have the most powerful poem on stage but if I read it in a monotone voice, it won’t sink into you as much as I want. Or I could absolutely read it in that monotone voice because that’s the kind of energy I want to give. You just need to know how your poem will present on stage.

LUX: Slam poetry is often both political and personal. What are some of the common themes that recur in the Slam Poetry scene?

Yomi Sode: What I find often in Poetry Slam is that the same themes will crop up along the lines of heartbreak, sexuality, rape, racial injustices, all those things there, are all packaged into a similar poem – but the way the poem approaches it is what is interesting to me. You have to believe in what you’re saying.

LUX: You’re involved in lots of poetry events going on in London – what do you think is the significance of nights like these for poets and poetry-lovers, as well as the community as a whole?

Yomi Sode: BoxedIn and Jawdance are not the only poetry nights that happen in London; there are a lot of mini poetry nights across London that people are not necessarily aware of. Those nights happen either weekly, monthly or bi-monthly or whatever it is, and they’re not in the limelight. I guess one of my aims with BoxedIn is that I’m going to encourage poets from these nights – other poets on the poetry scene – because my concern is that we’re always dipping in the same pool, picking out the same poets. And there are poets in and out of London doing some amazing things.

LUX: How would you describe the poetry circuits in large multicultural cities such as London? What needs changing, in your opinion?

Yomi Sode: It’s saturated in London. I feel like I’ve exhausted in London. And even then, there are still so many poets in London that we don’t know about. UniSlam is the national poetry event: there were folks from Glasgow, folks from Manchester, Leeds, Bristol, and I’m like this is what I’m talking about. It was just amazing to break out of London and find out what else is going on.

Read next: Geoffrey Kent on the rise of luxury adventure travel

LUX: How do you avoid creative burnout?

Yomi Sode: I allocate my time well. I say no to things often. I spend less time on social media now and I’m so used to coming off social media so regularly that I honestly have no reason to be on there anymore. I wanted to tackle the need to be on there every day – it was a pleasure to go offline for a while, then come back on to announce a new project. All that learning has been interesting for me – making space and time for my work.

LUX: These days there is a certain commercialism to creativity. In what ways would you say Slam poetry is able to resist commercialism, giving people who may not otherwise have a ‘true’ creative space a voice for self-empowerment?

Yomi Sode: Poets maintain a bridge between commerciality and their own individuality – whether we’re talking about Kate Tempest or Inua Ellams and his Barber Shop Chronicles which, last I checked was in Australia. It’s amazing stuff. A lot of my peers and the folks that I’ve grown up with on the scene are being used in adverts, and the purists, the poetry purists, see these adverts and go: that’s not poetry. And while it’s a massive clash of ideals, I can’t speak for another person’s choice. I can’t tell someone that they should be a purist when they might have a family to feed. People make their decisions for what they want to do. Poetry going commercial? It will happen. It’s up to the writer as to how they want to balance that. It’s their own journey going forwards.

Poet, musician and playwright Kate Tempest

LUX: Is there a poem that you feel you need to write, but have yet to?

Yomi Sode: There are poems that I’m waiting to write. I’m trying to eradicate the thoughts of writers’ block. I’m working towards a collection of poems.

LUX: What does poetry mean to you?

Yomi Sode: It’s an experience that’s life changing. Because you could be in the position where your life is in a certain way and that one person comes on stage and does something that speaks to how you’re feeling. That’s what poetry does, it gives that kind of permission to almost speak someone’s thoughts, and I think that that’s a beautiful thing.

Recent Comments