Antony Micallef in his London home turned studio. Photograph by Maryam Eisler

British artist Antony Micallef’s practice blurs the boundaries between painting and sculpture. His textural artworks are the result of a unique method that combines oil paint and beeswax to create striking, three-dimensional forms. Before the national lockdown, LUX contributing editor Maryam Eisler visited and photographed the artist in his London studio

Maryam Eisler: What made you decide to turn your home into a studio?

Antony Micallef: I have always loved this flat, and I think you really have to love the place where you work. I feel it has a lot of warmth and personality. I was very lucky to eventually buy a new flat on the same road, and the original intention was to use that as a studio, but after some time, I realised that the light in the new space wasn’t as good as my old flat. Getting paint on the walls for the first time was a bit like wearing your best clothes and jumping in a puddle of mud so I had to get rid of that preciousness! It is quite an intimate private space, and that’s the beauty of it. I don’t have many visitors here.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

Maryam Eisler: As a newcomer to your studio, I sense a great deal of physicality in both the act of painting but also in its end delivery – your works glide between painting and sculpture. They’re ‘weighty’ and solemn. And around the studio, there are lots of palette knives, and mountains of stacked paint.

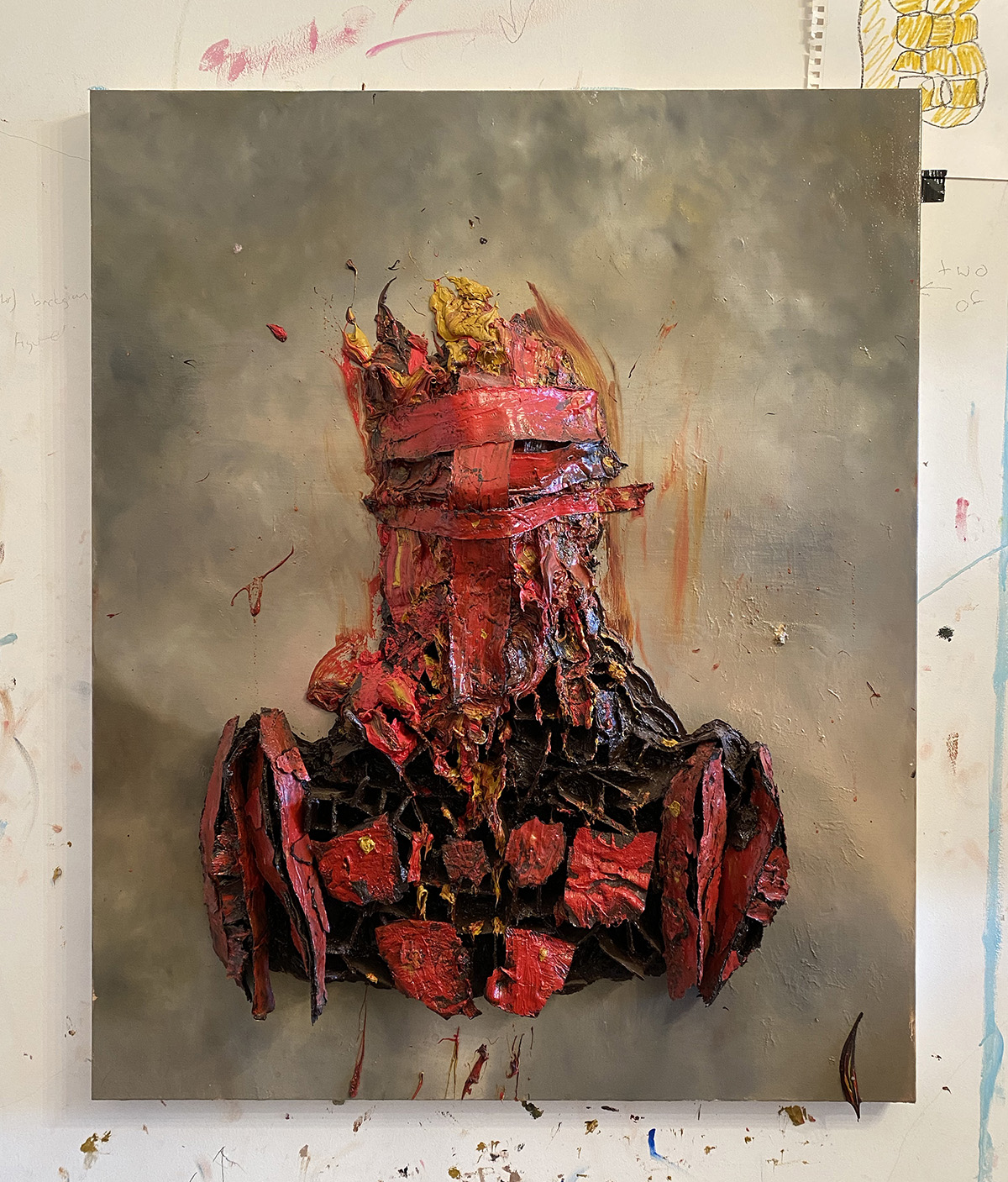

Antony Micallef: I am really glad you sense that. I am really interested in looking at the physicality of my paintings and in the objects they turn into. I’ve often found myself looking at the works of Tony Cragg and John Chamberlain, but also at rock formations while trekking, and early Alexander McQueen. I didn’t know how to fuse all these ideas together so I came up with a new method. I now mix beeswax and oil paint, which allows me to take the paint beyond its normal function. I use heavy palettes, loaded brushes, and loaded paint. It’s a forceful way of painting.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: Can you explain more about how you’ve developed and altered the capabilities and texture of paint?

Antony Micallef: I have changed oil paint to a physical texture, which is like dried oil strips and I manufacture the strips in my flat. If it were solid paint, it would fall off the canvas and so I’ve developed a honeycomb structure that I combine oil with beeswax. It’s a kind of laced oil, which I paint onto. It has spaces in between the strips; it’s solid because I have taken the oil out of it completely. It’s a slow process. I call them carcasses. You stick them down with more paint and then you build your figure, using them as a base.

Read more: The serene beauty of little-known Alpine resort Drei Zinnen

They’re kind of hybrids to me. You’re right in saying they lie somewhere between sculpture and paint. They become objects in their own right. Here, I am constructing this sort of Frankenstein figure from scratch! You see, every artist has an ego, and I just wanted to say that, ‘I’d done this. I came up with this process. My process is unique to me!’ It is such an interesting territory to own and I guess sharing this with the wider audience makes me feel good; it’s great for my mental health.

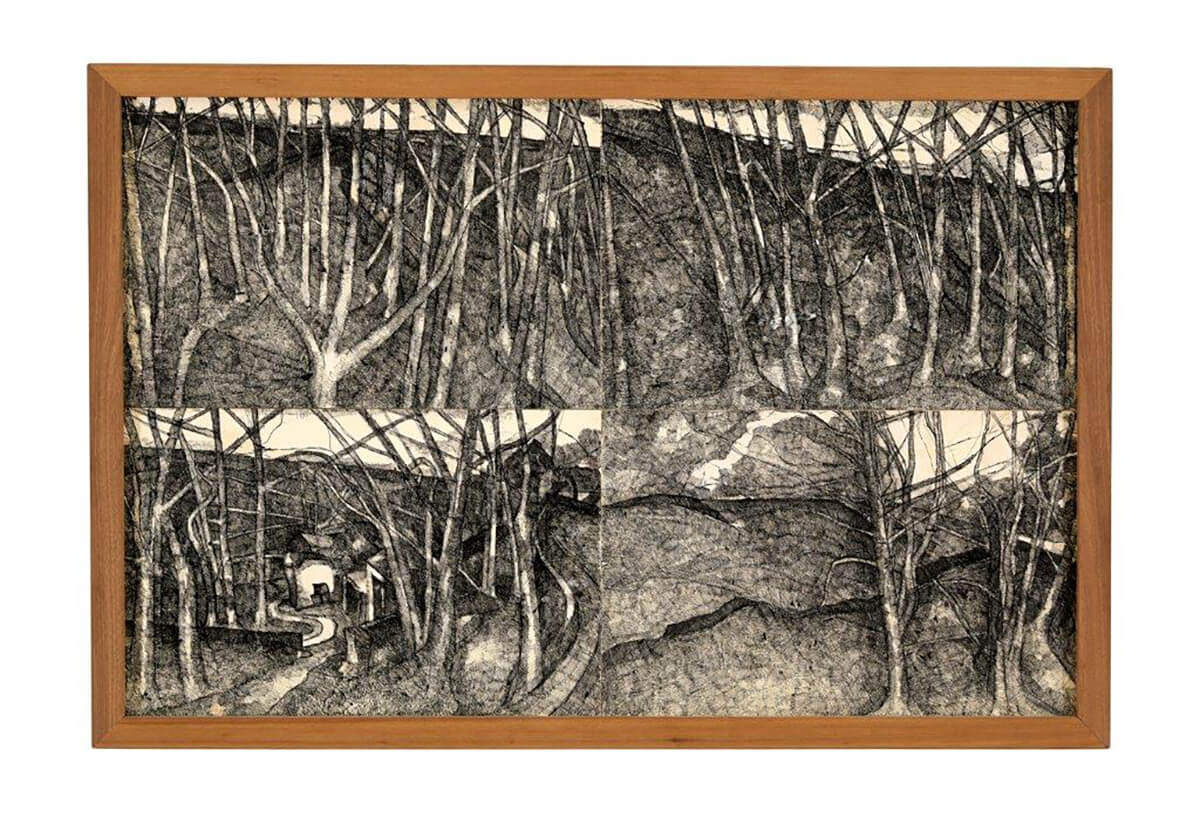

Constructing Auras No. 1, 2020, Antony Micallef, oil and beeswax on linen

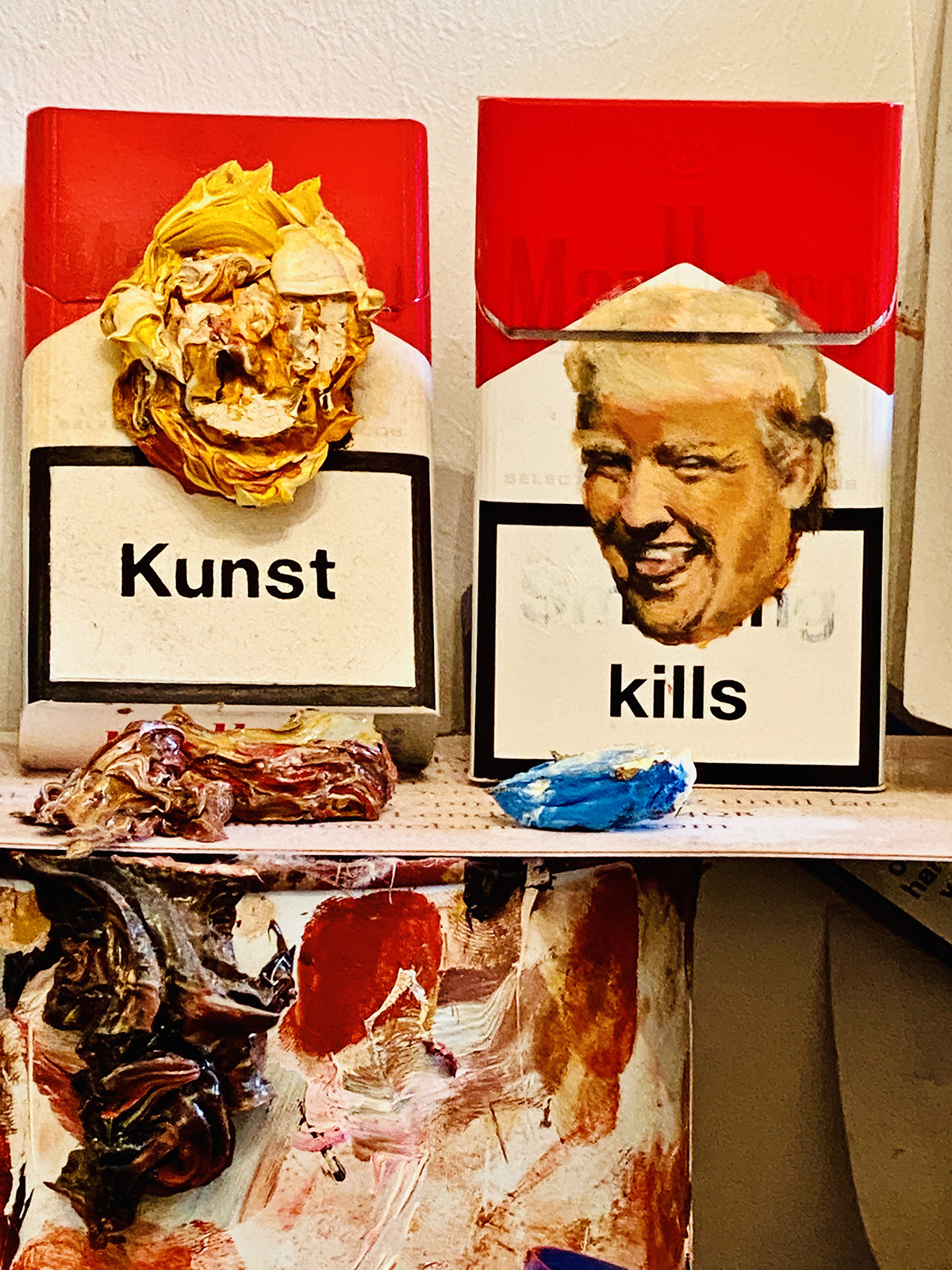

Maryam Eisler: I assume there’s a great deal of recycling going on in your work with unused strips for example.

Antony Micallef: Yes, you’ve touched on something important. All these bits you see here and there, I have cut them off the studio walls and off paintings. It’s all recycled paint. The studio in a sense then becomes part of the process, the walls, the floor… It is a bit like ‘harvesting’. That is why I am really precious with some of my pieces. I could never get these pieces again because the material comes off my studio walls. I have literally carved them off the wall over years. And that, to me, is a really important part of my practice.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: Have things changed much for you since lockdown?

Antony Micallef: I generally don’t see a lot of people, and I’ve seen even fewer this last year. Sometimes, it feels like you’re in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on a very small boat, but I have to say that having a visitor in your studio really helps. As an artist, you choose to be on your own, but when it’s inflicted onto you, it becomes something else.

Photograph by Maryam Eisler

Maryam Eisler: Can you tell me more about the body of work which you’ve been developing over a period of four years, and your recent show in Hong Kong?

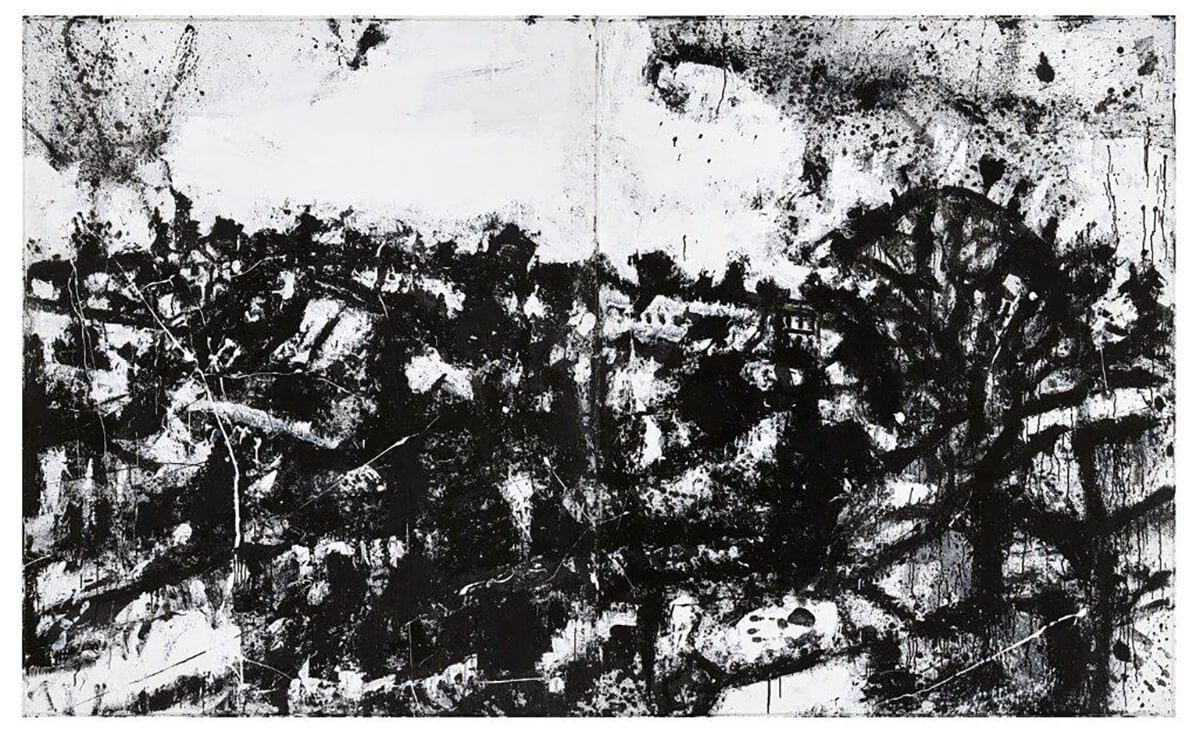

Antony Micallef: Constructing Auras was my tenth solo show. As you’re nearing the time when the work is about to be picked up, everything starts bubbling inside your head. You’ve lived with these creations for so long and they are about to flee the nest, but it gets to a point where art needs to live on its own in the outside world.

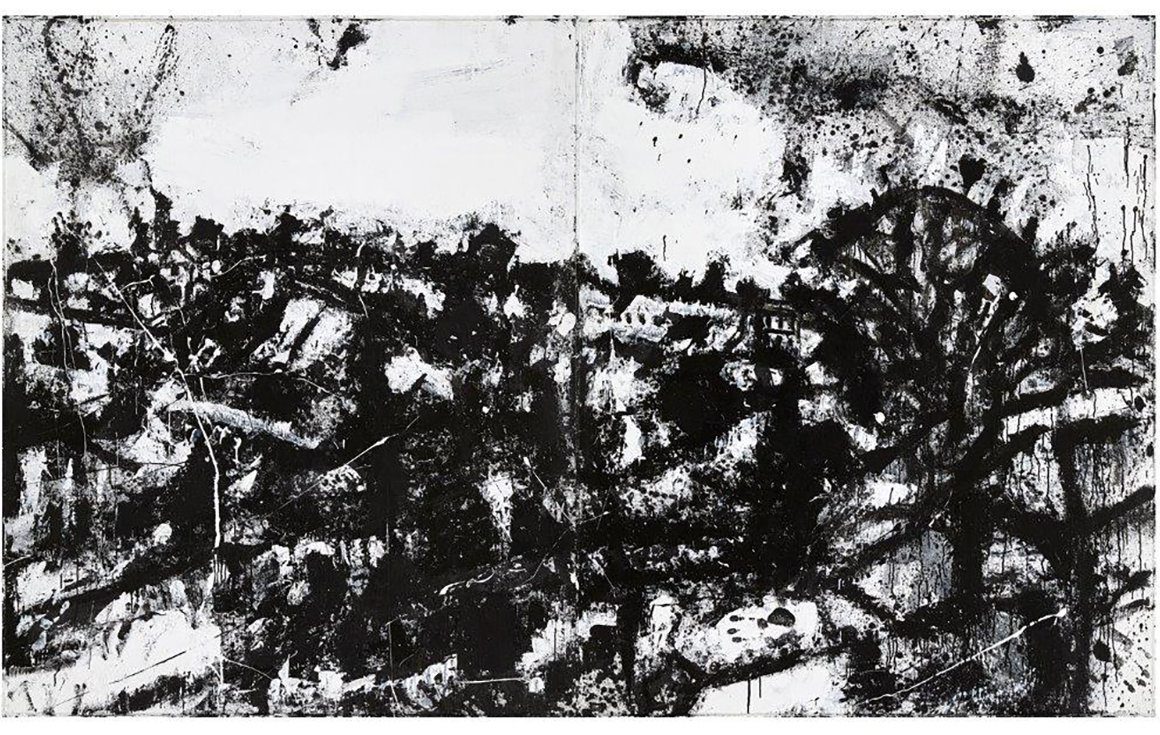

Constructing Auras No. 5, Antony Micallef

Maryam Eisler: How did studying under the renowned landscape artist John Virtue influence your practice?

Antony Micallef: I was taught by John at Plymouth University. I was really lucky to encounter him. He completely changed the way I thought about painting at the time. He taught me discipline. He also taught me how to look at life, figures, how to use a palette, all the mechanics. He was quite brutal with his teaching, which I loved. There was no faffing around. It was so nice to be taught by someone whose enthusiasm energises you.

Read more: Maria-Theresia Pongracz profiles 2021’s artist to watch Sofia Mitsola

I think the best art – that moves you and everyone else around you – is when you can feel that the creator has taken a risk. When you’ve pushed it to the limits of what it is capable of. I remember someone asking John: ‘How do you know when it’s finished?’ To which he replied, ‘Well, the train slows down. Imagine a train going as fast as it can, and when you get into the 90% level that is when the magic starts to happen. You then have to apply the breaks and it’s got to stop right before it hits that wall! If you can get it to 98%, that’s when and where it really happens.’ I always say it’s like throwing a jigsaw piece into the air. When it lands and it all fits together, it feels amazing!

Constructing Auras No. 8, 2017, Antony Micallef, oil and beeswax with raw pigment

Maryam Eisler: Do you ever bin your work?

Antony Micallef: Everybody bins their work, but you wouldn’t get those few you are really happy with if you didn’t!

Maryam Eisler: I can see the influence of the School of London painters in your work. Is that a conscious reference?

Antony Micallef: I never had the intention to paint like them, but I admire them, of course. When cooking, you have to have your own mixing bowl. You slowly find your own way of preparing a dish. The same holds true in painting.

The V&A had an amazing exhibition called Fashioned from Nature a few years ago. And that was pivotal for this body of work. Sometimes you walk into a show and something clicks.

View Antony Micallef’s portfolio: antonymicallef.com; @antonymicallef

Recent Comments