von Bartha’s flagship gallery behind a gas station in Basel. Photo by Ben Koechlin.

Stefan von Bartha. Photo by Simon Schwyzer

Swiss gallery von Bartha recently announced the opening of a new space in Copenhagen, becoming the first international gallery to lay down roots in the city. Here, LUX speaks to Stefan von Bartha, the gallery’s director, about von Bartha’s future, the impacts of the pandemic and the return of Art Basel

1. The Copenhagen gallery will be von Bartha’s first location outside of Switzerland. Why now?

One of the more positive aspects of the pandemic was the fact that we had the time to really think about and discuss the future of the gallery in depth. It became very clear that our physical gallery space was the core part of our operation that we can always rely on. During that time, when travelling and art fairs were not an option, it was the only place where we were able to show art and meet with our collectors.

Follow LUX on Instagram: luxthemagazine

While we hope that we never find ourselves in this situation again, we have been fortunate in that we have been able to build a closer and more personal connection with our collectors which is very valuable. Copenhagen has always been one of my favourite cities and we are excited to be the first international gallery to open a space there. Being able to open and connect with new audiences and collectors is very much in line with the future direction of the gallery.

2. Do you think things are shifting in terms of the city’s presence in the global art world?

A city like Copenhagen fits the profile of von Bartha with our primary space being in Basel and from my perspective, I think the more typical ‘gallery centric’ cities are facing more and more issues. I do believe that Copenhagen’s art scene will see a lot of growth over the next few years.

3. Why do you think there has been a recent increase in galleries opening spaces in unusual settings? Your Copenhagen gallery, for example, will be located in a former lighthouse.

I think there is a sense of fatigue with the more ‘typical’ gallery spaces. When we opened our new headquarters in Basel behind the gas station, everyone loved the concept, and we received a lot of positive feedback. So, a lighthouse makes total sense for us!

Record, 1994 by Barry Flanagan will on be display at von Bartha’s booth at Art Basel. Courtesy von Bartha and the artist. Photo by Andreas Zimmermann

4. Aside from digital exhibitions, how else did the restrictions of the pandemic alter the gallery’s structures?

I think the biggest change has been increased personal contact our collectors. Everyone had access to time, which is rare these days! We were able to speak with our artists and collectors at length and without the sense of being rushed.

Read more: Culture & Cuisine at La Fiermontina, Puglia, Italy

5. Are there any artists or art world developments that are particularly exciting you at the moment?

Opening a new gallery space in Copenhagen is exciting enough for me!

6. What can we expect from von Bartha’s presentation at this year’s edition of Art Basel?

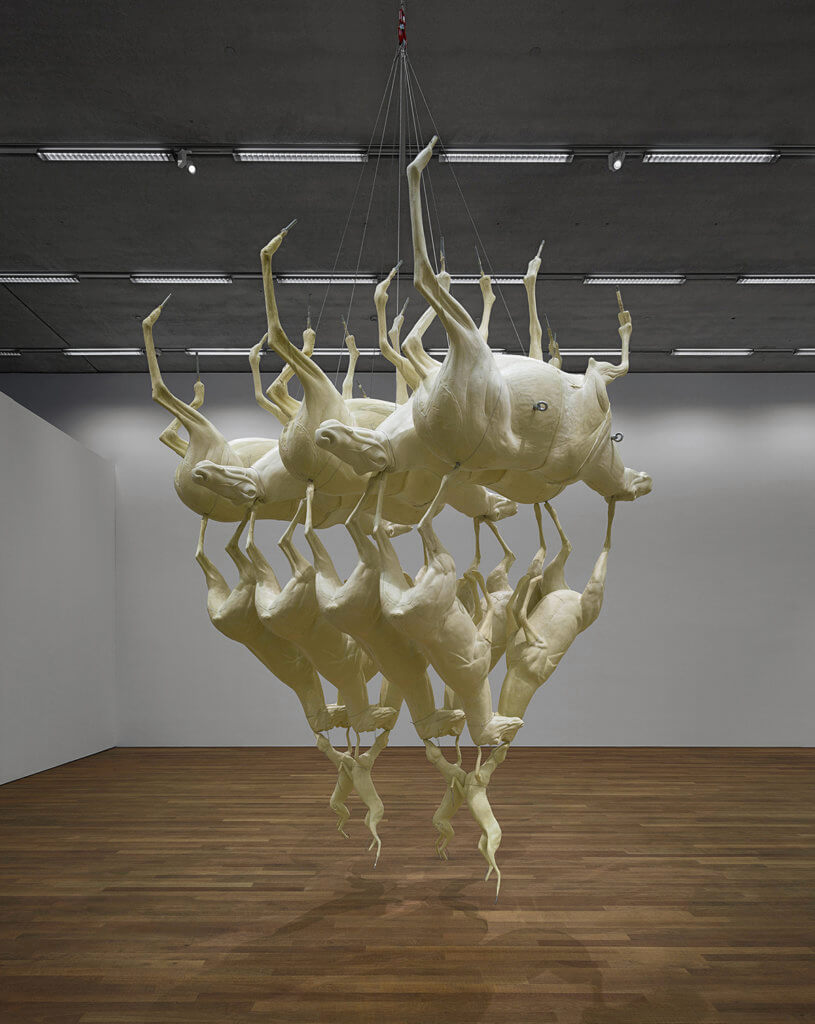

In general, I think we can expect one of the strongest and most exciting Art Basel fairs ever. All galleries will bring their best works as it is the first major fair to take place in two years. von Bartha will present a really exciting mix of leading contemporary artists in the gallery’s programme including Marina Adams, Imi Knoebel, Superflex, and Claudia Wieser alongside a selection of work by artists including Barry Flanagan, Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp, encouraging a thought-provoking discourse between contemporary and historical. The presentation will be complemented by a strong programme across the city including our collaboration on the opening of Imi Bar, a new permanent bar at the Volkshaus Basel Hotel, featuring artwork by German artist Imi Knoebel and at our flagship Basel space, we will be showing two exhibitions by Chilean-Swiss artist Francisco Sierra and Swiss artist Beat Zoderer (on view until 23 October 2021).

Find out more: vonbartha.com

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

As we celebrate the 100 year anniversary since women were given the vote in parliamentary elections, Angela Westwater, one of the art world’s pre-eminent gallerists, reflects upon the great women gallerists who have inspired her, and the changing landscape of the New York gallery scene over the past 40 years

Recent Comments