The Alps are at their most sublime when the sun is warm, the snow has given way to meadows, and the crowds are far away, says Darius Sanai. Here we focus on two legendary resorts which really come alive in the summer

Zermatt: The high peak paradise

Mention a luxury chalet in Zermatt to anyone with an ounce of snow in their blood, and they will immediately start to fantasize about the glorious off-piste of the Hohtälli, the vertiginous black runs down from Schwarzsee, the myriad routes down the back of the Rothorn. For chalets and Zermatt mean the ultimate in he-man (and she-woman) ski holidays on the highest runs in the Alps, for groups who can then relax in a super- luxe communal chalet and share stories.

There is, however, another and very different experience to be had in a chalet in Zermatt. Mine started with sitting outside on a broad balcony in a polo shirt, gazing up at the green foothills and rocky high peaks, birds and butterflies drifting past. The summer sun is strong here, but in the mountains the air is dry and there is always a hint of the glaciers in the breeze, so you never feel like you are sweltering.

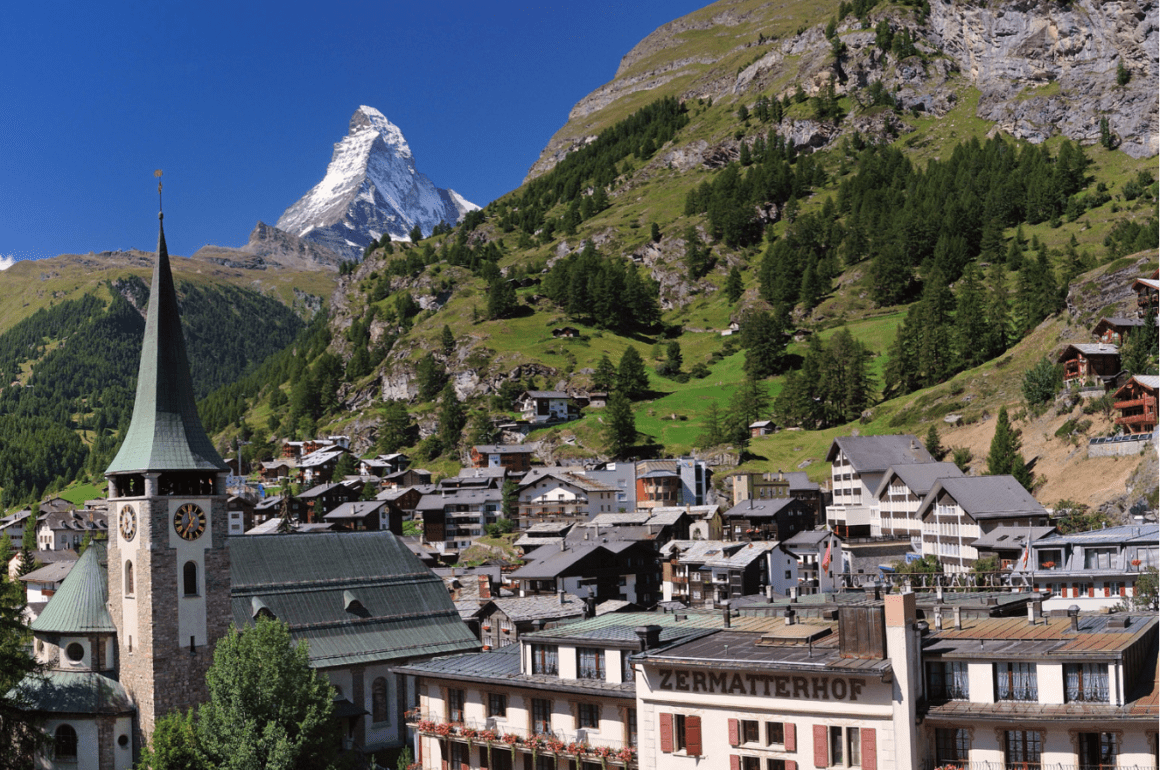

Zermatt is a glorious place in the summer, as its soaring peaks – it is surrounded by 30 mountains of over 4,000m in height, more than any other village in the Alps – are less frozen, less forbidding, more open to being explored than in the ski season. And while the village is the number one Alpine destination for summer holidays, it is still less crowded than in winter, when the entire populations of Moscow and Mayfair flock to the village under the Matterhorn.

Peak Season:

The village of Zermatt wears a cloak of green throughout the summer months, but the jagged Matterhorn retains its mantle of snow and ice

Chalet Helion, run by uber-swish chalet company Mountain Exposure, is one of the ultimate incarnations of its breed. Technically, although it’s a wood-panelled, chalet-style building, it’s not actually a chalet; rather it is an extensive lateral apartment running across the breadth and length of the construction. You get there via a three-minute taxi ride or five-minute walk from the main train station. Cross the rushing green Zermatt river, walk past the art nouveau-style Parkhotel Beau Site on a little knoll, and there it is.

On walking into the apartment, turn left into a vast, open-plan living room/dining room/kitchen area, with space to seat a party of 20. It sleeps eight people and is well organized for entertaining, as the living quarters can be closed off from the dining and chilling space, where there is also a cosy study.

Draw back the curtains and, beyond the broad balcony terrace, is the most magnificent view in Europe: an uninterrupted vista of the Matterhorn. It rises above the end of the valley like some supernatural thing, a giant, quasi- pyramidical, almost vertical rock formation, covered in thick snow and ice, surrounded by glaciers, standing above other mountains that are green with friendly summer pasture. It looks down with disdain, mocking us mere humans with our pathetic summer activities.

It is also mesmerizing. From the balcony at dawn, it glows rose like a Laurent-Perrier champagne; in the middle of the day, its least forbidding time, it is all silvers and whites; at dusk, it takes on its most frightening aspect, its darkness making you think of all the climbers who have fallen thousands of metres to their deaths on it. My father climbed the Matterhorn when he was young and made me promise I would not do it; he can rest assured from his own place in the skies that there is no danger of that.

The Matterhorn is Zermatt’s brand, adorning every poster, postcard, sticker and banner. But development means it has become harder and harder to find a room with a view of the mountain itself rather than a view of the newest building. And this is what makes Chalet Helion so special, as its vista, from a gentle slope above the village centre, is uninterrupted.

But the mountain isn’t the sole reason to go to Zermatt. There’s only a certain amount of time you can stare at the almighty, after all. Just down from Chalet Helion is the lift system that takes you up to the Sunnegga-Rothorn mountain. A train tunnel bores through the bare granite and, three minutes later, you emerge into a wonderland.

Sunnegga, the first stop, is above the treeline and at the top of the steep foothills that border one side of the village. From here, unlike down in the valley, you see that the Matterhorn is just one of dozens of massive, icy, knife-edged peaks above the resort. Directly in front of you rise four 4,000m-peaks, culminating in the Weisshorn, shaped like a gigantic shark’s fin and, at 4,512 metres, even higher than the Matterhorn. To the left, snowy pinnacles hint at even higher summits. To see those, we climbed into the

cable car to the very top of this lift system, the 3,100-metre high Unter Rothorn (recently rebranded as just Rothorn, but as there are three variations on Rothorn around here, I prefer to stick to its original name). We stepped out into eye-watering sunshine and crunched onto a patch of snow left over from winter: 3,100 metres is high indeed. The peeking peaks from the previous stop now revealed themselves as six huge mountains layered in unimaginably thick snow and ice, rising above the Gornergrat ridge in between us.

The highest of these, Monte Rosa, looked like a giant’s meringue, massive but without the character or shape of the others. At 4,634 metres, it makes up in heft what it lacks in shapeliness: you can make out the other face of Monte Rosa quite clearly when standing on the roof of Milan’s cathedral, more than 100 miles away. (As a comparison, Britain’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, is 1,343 metres, and Germany’s highest, the Zugspitze, is 2,963 metres.)

Zermatt is famed for its mountain restaurants, but that morning I had gone shopping at the local Coop (which in Switzerland means amazing fresh, local ingredients, from radishes to mountain cheese), and we picnicked instead, sat on a rock by the side of a pewter-coloured lake, in which the Matterhorn was perfectly reflected. Here, at Stelisee, you are at peace with the mountains above and the valleys below. The sun bakes you, apart from an occasional wisp of wind which wafts down from the glacier like nature’s own cooling mist spray. Butterflies, bees and millions of grasshoppers play among the fields of wildflowers all around. Even the Matterhorn from here looks less dark, more pretty. Never has an air-dried beef sandwich with freshly grated horseradish tasted more perfect.

Walking down, we came across another lake, Leisee, deep green in colour. Fittingly, amid the sea of wildflowers surrounding this one, was a confederacy of tiny green frogs. Not much bigger than an adult fingernail, you had to be careful not to tread on them as you walked along the path.

Dinner in Zermatt comes with reservations in both sense of the word: you need to book, as the place is heaving in season; and you always feel slightly annoyed that the restaurants, however well deserved their culinary reputation, have no Matterhorn view, as they are clustered in the village centre.

This was a further joy of Chalet Helion. On most nights we cooked, and ate and drank local Valais wine (vibrant Fendant whites, deep Cornalin reds) on our balcony or at the dining table with our private, picture window view of the mountain fading to grey. After which, a Havana on the balcony: one clear night we could make out the helmet lights of the night climbers on the sheer rockface of the mountain.

On one evening, Mountain Exposure’s charismatic owner, Donald Scott, a British snow- phile who came to Zermatt and never left, brought one of the company’s chefs to create us a fabulous, complex Swiss mountain meal. Our dining area was transformed into a restaurant, an option open to any guest who pays.

We will certainly be back, for the view from Chalet Helion, and its entire experience, is as eternal as it is wondrous.

Chalet Helion is available summer and winter from Mountain Exposure, mountainexposure.com. For general information, see zermatt.ch

SPA AT MONT CERVIN PALACE

For decades Mont Cervin Palace has been the byword for glamour for all visitors to Zermatt. A well-kept secret is that this five-star hotel in the heart of the village has a beautiful, 25-metre indoor pool, and an outdoor spa pool and garden as part of its hidden annexe. The garden and outdoor pool (which is open year-round) have a dramatic view of the mountains from the village centre, and the indoor pool and hydrotherapy area are the best places in the valley to retreat to when the weather closes in – or if you want some cross-training exercise after a day’s skiing and hiking. The best news? They are open to non-residents, for a fee. montcervinpalace.ch

Gstaad: Alpine chic with a twist

Gstaad has a reputation as a gentle place, perhaps more suited to high net worth retirees wanting a peaceful and safe place close to their money (in Swiss bank accounts) in which to holiday. But that reputation vanished before my eyes as soon as I set foot into the garden of The Alpina hotel.

Before me, a long outdoor pool, lined by teak decking and a few (not too many – this is Gstaad) sunloungers. Around it was a garden in full bloom; beyond that the rooves of this traditional village (The Alpina is on a small plateau above the centre), all framed by an amphitheatre of forest, meadow and mountain. Far away were high rocky peaks and glaciers. It was hot in the sun, and a first morning spent in and by the pool, accompanied by the occasional cocktail, was bliss due to true exclusivity. At that moment, in any number of luxury Mediterranean hotels, super- wealthy guests would be jostling for space by the poolside in neat rows, trying to attract the attention of overstressed serving staff, waiting far too long for their drinks to arrive.

We, on the other hand, had the attention of numerous waiters (there were a few other guests, but more than enough staff to deal with them) and sufficient space to have a conversation about my tax affairs on my phone with no danger of anyone overhearing (not that I would be so vulgar).

Suite Dreams:

Swiss artisans have created the interiors at The Alpina, using local stone and period woodwork

Wandering inside a neat little chalet, we found stairs to take us down to a cavernous and exquisitely finished spa area. One corridor led to a salt room, where even the walls were seemingly made of salt, another to the treatment rooms, and another to a quiet cafe area lined with photographic books and jugs containing various herb-flavoured waters.

Beyond that, another pool, inside the cavern, some 25 metres long, bookended by spa pools and crowned by a glass cupola looking into the garden above. If the weather ever failed, this would be the place to spend the day, as we discovered the next day when a thunderstorm swept in. The Alps form the border of the hot Mediterranean climate zone and rainy northern Europe, and you can feel the battle between one and the other, day by day.

When the sun reappeared we headed up the round, green mountain facing us – more a fairytale hill than a dramatic Alp – in a gondola and found a large chalet restaurant, Wispile, serving fondues made with cheese from the chalet’s own cows, clearly visible in the pasture above. The view was over the village and the wooded foothills and forests beyond, out towards Lake Geneva. Wispile also has a menagerie of animals, from llamas to pigs and goats, which families can help to feed.

If Wispile is all that you expect from a Swiss Alpine hut, the evening offering at The Alpina is something else entirely. The owners of this new uber-luxe hotel, which was clearly built to compete with, if not actually outdo, the celebrated Palace hotel down the road, wanted the best of world cuisine in a village not renowned for its cosmopolitan food offerings.

For MEGU, a Japanese restaurant in the heart of the hotel that is an outpost of the celebrated New York establishment of the same name, they enticed and employed master chefs from Japan. It shows: the sushi was magnificent. A taste that I will try and remember for the rest of my life is the signature crispy asparagus with crumbed Japanese rice crackers, chilli and lemon. The Oriental salad (various Chinese vegetables, nuts, seeds, sashimi of Dover sole and sesame oil) was also unique and memorable. Stone-grilled wagyu chateaubriand with a fresh (not powdered) wasabi soy reduction was also fabulously vibrant. I’d take MEGU over Nobu and Zuma, if only it were in London.

There was also Sommet, the hotel’s other signature restaurant, which holds two Michelin stars. It is hard to tell which is more important. Sommet has the better location, a big contemporary dining room with a view of pool and mountains, and seating on the broad terrace; MEGU is the cosy space behind the bar at the heart of the hotel. Sommet has 18/20 from the Gault et Millau guide and is refreshingly fuss- free. The seabass with artichokes, hazelnuts and spinach had simple, highly defined flavours, and the organic salmon steak with tomato and olive risotto was cooked with great attention to detail. Sommet’s chef has the confidence to let his quality ingredients, combinations and technique speak for themselves, and this is contemporary fine dining of the most appealing kind.

These were two of my most notable meals of the year, anywhere in the world, to the extent that I would make a journey to the hotel just to eat there, even if I couldn’t stay there. But for overall experience, they can’t quite match that of sitting by the outdoor pool, looking at the glowing green of the Alps, under the deep blue of the mountain sky, in utter peace, while sipping a perfectly made margarita, served by an unhassled staff member who knows exactly when to ask whether I’d like another one. That may not have been the first line of the owners’ business plan when they opened The Alpina, but they have succeeded in making Gstaad a true summer holiday destination beyond, I suspect, even their wildest dreams.

Recent Comments